Chapter XIV: Return to the Philippines

Leyte and Mindoro

General MacArthur’s staff had begun preliminary planning for the recapture of the Philippines early in 1943. This early planning was repeatedly revised in accordance with changing tactical developments and instructions from the Joint Chiefs of Staff. By March 1944 the war in the Pacific was going well for the Allies. The Marshalls had been seized and were being converted into a powerful forward base. The Admiralties were under attack, and the weak Japanese resistance indicated that capture of these islands was merely a matter of time. On 12 March the Joint Chiefs directed MacArthur to prepare detailed plans for an attack on Mindanao, southernmost of the major islands of the Philippines, tentatively setting 15 November 1944 as the date for the first landing. In mid-June MacArthur issued his plan for a return to the islands. He called for a small-scale attack at Sarangani Bay, on the southern coast of Mindanao, on 25 October and construction of a minor air base there as soon as possible. On 15 November a major amphibious attack would be launched against Leyte in the central Philippines and an extensive base built on that island to support an attack on Luzon.1

Engineer Planning

The first assaults on the Philippines were assigned to Sixth Army. In many respects, operations would be similar to those in New Guinea. The objective areas would be softened up through aerial and naval bombardments, amphibious landings made, the Japanese destroyed or driven away from the beaches, and airfield and base construction begun. Early in July, Sturgis and his staff, recently moved from Finschhafen to Hollandia, were briefed on the KING or K series of operations, scheduled for the southern and central Philippines. At this time, little up-to-date information was to be had on those areas. The photography of Sarangani Bay was far from complete and “... as for Leyte ... , there was no photography at all from which local conditions could be determined and construction plans based.”2

A most important matter was the weather. While temperatures in the Philippines varied little, most of the islands had two pronounced seasons, a dry and a wet, determined to a large extent by the prevailing winds, the

northeast monsoons, lasting from October to April, and the southwest monsoons, which continued from May to September. This pattern of winds brought rain to the eastern parts of the mountainous islands during the northeast monsoon and to the western parts during the southwest monsoon. Southern Mindanao had no pronounced wet or dry season. MacArthur’s plans called for a landing on Leyte during the rainy season. October and November were, moreover, the months of strong winds and typhoons. Since a great deal of construction would have to be done, the adverse weather, together with the inadequate number of engineer units and the short time in which to do the work, would create almost insuperable problems.3

An Army Service Command

During the New Guinea Campaign the need for an efficient construction and logistics organization in a task force area in the first days of an operation had become apparent. Hastily assembled task force engineer staffs had often not been able to meet satisfactorily the numerous and frequently unforeseen problems which arose. The need for a construction and supply agency in the combat zone in the early phases of a major assault in the Philippines would be even more critical, since such an operation would be more extensive in scope than any undertaken previously. A solution to the problem would be for USASOS SWPA to organize a construction and logistics agency, and before the scheduled assault, transfer it to Sixth Army, which would move it forward as soon as possible during the combat phase, so that no time would be lost either in providing combat support or in beginning base and airfield construction. When Sixth Army subsequently transferred the newly built base to USASOS, much of the organization, particularly the part needed for base operations, would go back to USASOS. With this procedure, there would be a minimum of dislocation when the transfer was made.4

In line with this reasoning, USASOS activated the Army Service Command (ASCOM) at Brisbane on 23 July 1944. Casey, now a major general, and on detached service from GHQ, was placed in command; Sverdrup became MacArthur’s acting chief engineer. During August Casey organized his headquarters, obtaining most of his staff from units of USASOS, particularly the headquarters of the 5201st Construction Brigade. Colonel Robinson, head of the brigade, became Casey’s engineer. The ASCOM staff prepared standing operating procedures and began to requisition supplies for the construction of a base at Sarangani Bay and another on the east coast of Leyte. Since the building of airfields and bases was to be one of ASCOM’s major functions, a large number of engineer units were scheduled for temporary transfer to the new command. Part of the men assigned to ASCOM headquarters were to make plans and preparations for constructing a particular

base, and part of them, transferred to ASCOM later on, were to be responsible for operating it. The latter, together with a number of units, would return to USASOS when the combat phase was over and the base passed to USASOS. As soon as a base was a going concern, those responsible for planning would begin to make plans and preparations for the next one. A hindrance to early planning was that ASCOM was at Brisbane and Sixth Army headquarters at Hollandia. Coordination was difficult.5

On 27 August MacArthur announced a schedule of operations which called for attacks on dates later than those he had set in his plan of mid-June. There was to be an assault on the Talaud Islands, halfway between Morotai and Mindanao, on 15 October; on Sarangani Bay on 15 November; and on Leyte on 20 December. While the later scheduling of operations would give the engineers more time for planning, they would still have to build the extensive base on Leyte during the rainy season. Planning was moving ahead satisfactorily. Since construction and logistic support were expected to be generally of far greater importance than combat, Casey’s staff had to do comprehensive planning. Early in September ASCOM moved to Hollandia, where major theater Headquarters were located, and better coordination, particularly with Sixth Army engineers, was possible. By the second week of the month, planning was practically complete. Requisitions for all classes of supplies and equipment had been submitted to USASOS. On the 15th ASCOM was transferred to Sixth Army, where it was placed on a corps level; Casey would be directly responsible to General Krueger.6

The Assault Schedule Revised

From the loth to the 14th of September Admiral Halsey’s carrier fleet made a number of strikes against the central and southern Philippine islands. The weak resistance his flyers encountered was quite convincing evidence that Japanese strength in those parts of the archipelago was fairly well depleted. Halsey informed Nimitz that the area was “wide open.” On the 14th he recommended that the operations planned against Yap, Talaud, and Sarangani Bay be canceled and that Leyte be seized immediately. Nimitz radioed Halsey’s suggestion to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, then meeting with the British Chiefs of Staff at the OCTAGON Conference in Quebec. Marshall immediately asked MacArthur for his views regarding the speeding up of the attack schedule; MacArthur replied two days later, agreeing to cancellation of the operations as Halsey recommended. The Joint Chiefs at once instructed MacArthur to move directly against Leyte and set the 20th of October as the day for the attack.7

Intensified Planning for Leyte

Concentrating henceforth on planning for the Leyte (K-2) operation the engineers

had numerous problems to deal with. Not only had the target date been moved up sixty days but the new objective area was some 350 miles more distant. Leyte, about 600 miles north of the airfields on Morotai and 1,000 miles northwest of those on Biak, was, for all practical purposes, beyond fighter and medium-bomber range. The risks incident to carrying on extended operations without land-based air support were considerable. It was of the utmost importance that the engineers have airfields ready as soon as naval air support was withdrawn; since the assault was scheduled for the beginning of the rainy season, this might not be easy. To make matters worse, only sketchy information was to be had regarding the island’s terrain. Leyte was still too far from the most forward bases for land-based reconnaissance planes. Flyers with Halsey’s carrier fleet were the first to photograph the target area, but the films brought back, when developed, showed important terrain features obscured by clouds. Pictures taken during the subsequent weeks were not much better.8

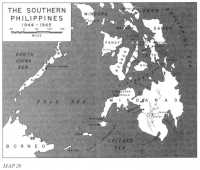

Fortunately, a considerable amount of information was available in topographic studies made before the war; the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey had prepared hydrographic studies of beach areas which contained especially valuable data. The eighth largest island of the archipelago, Leyte was some 115 miles long, 43 miles wide at the north, and 16 miles wide at the center. (Map 28) Mountainous and, for the most part, heavily wooded, it had two principal lowlands. The first, Leyte Valley, stretching across the northeastern part of the island from Leyte Gulf on the east to Carigara Bay on the north, had many streams and numerous rice paddies; it would not be suitable for extensive construction, except perhaps during the dry season. The second, the Ormoc plain, on the west coast, would in all probability not be the scene of decisive fighting or of a great deal of construction. Most of the island’s roads were in the northeast, and radiated from the capital, Tacloban, located in the Leyte Valley on the east coast. The island’s few paved thoroughfare’s had only a thin and narrow surface of bitumen. Facilities for supporting modern war were few. No definite information was on hand regarding the number of airfields or their condition, but it was known that the Japanese had been working on several. The most important, Tacloban, a 5,000-foot prewar commercial field on the Cataisan Peninsula, two miles southeast of the capital, was undoubtedly operational. In central Leyte, located near the dirt road running west from the coastal town of Dulag to Burauen were four fields—Dulag, San Pablo, Bayug, and Buri. San Pablo, overgrown with weeds. was not in use; the other three seemed to be operational. There were apparently additional fields but little was known about them. Most of the island’s population lived on farms or in small villages, called barrios.9 Even Tacloban,

Map 28: The Southern Philippines, 1944–1945

according to Sturgis was “... merely an overgrown village with a few dilapidated warehouses and public buildings and limited berthing facilities for two Liberty ships.”10

Neither combat nor service engineers had enough time for adequate planning. Insofar as combat was concerned, a major obstacle arose from the fact that XIV Corps, assigned to operations on Leyte, had to be kept on Bougainville for mop-up operations. The Central Pacific’s XXIV Corps, scheduled for the assault on Yap and already en route to its destination, was diverted to Leyte. The engineer units of that corps, prepared for a landing on a small Pacific island, had to be supplied with more equipment, and eventually more engineer units would have to be sent in to support XXIV Corps. A second matter of importance was bridging. Combat on Leyte, unlike that on New Guinea, would probably require numerous stream crossings, since the American

forces would most certainly have to move inland to destroy the Japanese. There were not enough bridging units or sufficient amounts of bridging equipment in the theater to support an extensive overland advance. On hand were one heavy ponton battalion—the 556th—and three light ponton companies—the 506th, 510th, and 530th—and all four had only a minimum of equipment. Of these units, the 556th and 530th were assigned to Sixth Army; the 506th, to X Corps. The 510th was already committed to support the operations on Morotai. Bailey bridging, ideal for semi-permanent fixed spans, was in short supply; only a few hundred feet of it were in New Guinea. Most of this was collected and loaded on Leyte-bound vessels which happened to be handy. Sturgis believed that the ponton units, at least part of the time, would have to be put to building fixed bridges on Leyte so that floating equipment could be moved forward as rapidly as possible to support the advance of the infantry.11

ASCOM engineers were likewise pressed for time for adequate planning. Their immediate responsibility was the all-important one of building the critically needed airfields. They were to construct four. One runway, 5,000 feet long, was to be ready for fighters within 5 days after the first landing. But airfields were only one of many responsibilities. ASCOM was to build a base to provide logistical support for 200,000 air and ground troops, including port facilities, warehouses, hospitals, and headquarters for various commands. Port facilities were to include floating docks for four Libertys, to be ready within 30 days. Eventually, ASCOM was to complete six fixed wharves for Libertys, each to take two ships; the first wharf was to be ready within 45 days. Seventeen lighter jetties were to be built. ASCOM was to provide 12,000 hospital beds, most of them in tents. Initially, gasoline was to be furnished by barges anchored offshore; meanwhile, ASCOM was to build two small fuel jetties and begin work on bolted tanks of 2,000-barrel capacity each. Northern Leyte and southern Samar Island were, in addition, to be the site of an extensive naval base. To accomplish his construction program, Casey had a sizable number of engineer units. He had, among others, 15 aviation battalions, 3 construction battalions, 2 port construction and repair groups, and 7 dump truck companies. Of the 43,183 men assigned to ASCOM, 21,097, or approximately 47 percent, were engineers. Supply posed one of the most vexing problems. There was less than a month left to finish planning for Leyte, submit requisitions, and load the supplies on transports. Many items scheduled for Talaud and Sarangani Bay had to be diverted willy-nilly to Leyte, whether needed there or not.12

Amphibious Operations—Planning

Of all the amphibious assaults made in the Pacific, the Leyte operation was the only one in which both the engineer special brigades of the Southwest Pacific

and the shore party organizations of the Central Pacific were to be used. Two major landings were planned for the island’s east coast—one just below Tacloban, the other, some fifteen miles farther south near the town of Dulag. The 2nd Special Brigade, less one boat and shore regiment, was to help land the 1st Cavalry Division and the 24th Division of X Corps near Tacloban. General Heavey made arrangements with VII Amphibious Force to transport 290 LCMs, 57 LCVPs, and 38 auxiliary craft to the target area; 130 LCMs and 42 LCVPs were to participate in the A-day landings. This was to be by far the largest movement of small craft in any operation made in the Southwest Pacific up to this time. At Dulag, two combat group headquarters with three combat battalions each were to do the shore party work for the 7th and 96th Infantry Divisions of XXIV Corps.13

The Assault

On 19 October two naval task forces of the Third and Seventh Fleets approached the east coast of Leyte. Three islands in Leyte Gulf had been occupied a few days before and rather extensive mine sweeping operations carried on to make the offshore waters safer for amphibious operations. As already indicated, the tactical plan called for the landing of two corps on the east coast. X Corps, comprising the 1st Cavalry Division and 24th Division (less one RCT), was to land on the three miles of beaches south of the Cataisan Peninsula and north of the Palo River. XXIV Corps, made up of the 7th and 96th Divisions, was to come ashore near the town of Dulag. One RCT of the 24th Division was to land at Panaon Island southeast of Leyte and secure the narrow strait to enable motor torpedo boats to proceed into Sogod Bay and the Mindanao Sea. The major assaults were to be made on beaches near the two airdrome areas—the early capture of Tacloban airdrome and the four fields in central Leyte was essential.14 The plan of campaign called for X Corps to advance northwest towards Carigara Bay and thence southward through the mountains toward Ormoc on the west coast. XXIV Corps was to drive across the narrow waist of the island and then advance northwest toward Ormoc to link up with X Corps.

On the morning of the loth the assault began as scheduled. The weather was ideal. The sea was calm, with the surf between one and two feet high. In the X Corps area, landings were made at White Beach to the north and Red Beach to the south. No mines or underwater obstacles were encountered. Japanese opposition was unexpectedly light, the principal interference being fire, at times fairly heavy, from five 75-mm. guns emplaced in jungle southwest of Red Beach. Four LSTs received direct hits and a fifth was set on fire; shell fragments damaged four engineer LCMs.

It was soon evident that Red Beach was poor, with water so shallow that only

one LST could get close enough to make unloading practicable. Hydrographic charts of the Coast and Geodetic Survey, used extensively in planning, had clearly indicated shallow water, as well as swampy terrain between the shoreline and Highway 1, which paralleled the coast. But the tactical plan, which called for X Corps to advance northwest from the beaches, required a landing north of the Palo River; obstacles at the beaches would simply have to be overcome in one way or another. The Navy, also aware of the unsatisfactory conditions offshore, had planned to build ponton causeways but could not get the ponton cubes in time to transport them to Red Beach; plans were then made to transfer cubes from the Dulag area, if necessary. To add to the confusion, naval beach parties, reconnoitering offshore the day before the landing, had erroneously reported the water deeper than it was. Ponton cubes, urgently requested from Dulag on the morning of A-day, did not arrive until that evening. Early the next morning, 21 October, unloading began over the floating piers, but only one LST was able to unload that day. Some transports were transferred to White Beach, where all vessels had unloaded and retracted by the end of the second day. Others proceeded to the beaches on the Cataisan Peninsula, where they unloaded thousands of tons of supplies, which the shore parties piled up on the airstrip.15

The shore parties at Red and White Beaches had a hard time moving supplies off the beach. Inland, 00 to 300 yards, was a series of swamps, and between them the Japanese had constructed antitank ditches. These obstacles, together with the lack of roads from the beaches, caused not a little congestion. Work was, moreover, interrupted by frequent air raids and alerts, as the Japanese mustered their dwindling air strength in a determined effort to disrupt the landing. The raids caused no serious damage, but the many alerts meant lack of sleep and near exhaustion for the shore parties. Some of the men were ordered to support the combat troops, which put an added burden on those remaining on the beaches. A major problem was getting a road through from Red Beach to Highway Under orders from the corps commander, the 339th Construction Battalion was attempting to build one across a swamp 600 feet wide, beyond which lay a mile of flooded rice paddies. Going ashore on A plus 1, Sturgis, recently promoted to brigadier general, found bulldozers and other equipment stuck in mud and water. Making a quick reconnaissance with the S-3 of the 339th, he found a fairly dry though somewhat longer route a short distance to the south. He had the unit transferred to this location, where it built a 3-lane road to the highway in a few days.16

Despite the obstacles, unloading schedules were satisfactorily met, including those for Green Beach on Panaon Island, where no difficulties were encountered.

When they hit their full stride on the Leyte beaches, the amphibian engineers were unloading approximately 100 tons of cargo an hour, probably a record for SWPA up to that time. On the average, they unloaded an APA (transport, attack), which carried some 1,300 troops and 450 tons of supplies, in four and one-half hours; the unloading of some Libertys, with their larger cargoes, took considerably longer.17

Efficient operations were in part the result of steadily improving teamwork of the engineers and the Navy. The apprehensiveness with which Navy men had regarded amphibian engineer operations when the 2nd Brigade first arrived in the theater a year and a half earlier was by now largely a thing of the past. “The 7th Amphibious Force and 2nd Engineer Special Brigade,” wrote Rear Adm. Daniel E. Barbey, commander of VII Amphibious Force, “have been associated in numerous amphibious operations ... complete understanding has been achieved through this close association and was reflected in the smoothness with which the Leyte landing progressed.”18 General Heavey was of the same opinion. He pointed out that the successful results at Leyte could at least in part be ascribed to “the fact that this Brigade has been associated with Seventh Amphibious Force in numerous preceding operations and knew its methods and many of its beach personnel. ...”19

Responsibilities of naval and amphibian engineer units assigned to task forces had become more clearly defined as the result of lessons learned in the course of actual landings. In all assault operations, the amphibious brigades had been under the control of Seventh Fleet. Landing craft operated by Navy personnel usually carried the first waves of infantry to shore. In the long forward movements, the Seventh Fleet transported the amphibian engineers’ craft. The fact that the amphibian engineers brought in part of the troops and subsequently engaged in resupply missions along the shore or from island to island was of distinct advantage to the Navy. Probably the major benefit was that the Seventh Fleet could withdraw its assault forces from a forward area at a relatively early time.20

At Dulag, also, the weather was fair and the seas calm on A-day. Demolition crews easily removed the few underwater obstacles found along the beaches. There were no coral reefs, and offshore slopes were steep enough to permit expeditious unloading—LSTs, LCMs, LCVPs, and Dukws carried men and supplies from ship to shore with little or no trouble. Firm sandy beaches held up well under truck traffic. Japanese opposition was lacking at the beaches, but here, as at Red and White beaches, congestion became something of a problem. Because of the danger of air attacks, the Navy wanted its ships unloaded and out of Leyte Gulf as soon as possible; at the same time, the infantry, beginning to meet stiff resistance inland, was not able to advance as rapidly as had been hoped. Nevertheless, work proceeded satisfactorily. Dozers of the shore party battalions, landed early in the operation,

were used to cut trails from the beaches and prepare dump areas. One company from each combat battalion provided security for the battalion as far as 800 yards inland. Neither occasional enemy rifle fire nor rainy weather later on interfered seriously with the work of the shore parties. The shore party battalions of the 7th and 96th Divisions, in the words of one observer, “worked at such speed and efficiency that all passenger ships were unloaded of their equipment in 25 hours and all cargo ships were unloaded in 44 hours, enabling them to leave Leyte Gulf.”21

ASCOM—Initial Operations

ASCOM’s most important task—the building of airfields—had to be begun as soon as possible in view of the fact that the American forces on Leyte were without land-based air support and the Japanese fleet was known to be operating in Philippine waters. Urgently needed were four all-weather fields. The one at Tacloban and the three in central Leyte were to be improved as quickly as possible. All, except Tacloban, would require much work to bring them up to minimum standards.

ASCOM personnel and units arrived early in the operation. Casey with some members of his staff came ashore on A-day; two days later the advance echelon of ASCOM headquarters arrived. Since the Japanese at this time still held the area at Palo allocated to headquarters, Casey installed his staff in a large house near Tacloban, set up tents on the grounds for overflow personnel, and organized a system of perimeter defense to guard against Japanese infiltrators. He had organized two subordinate commands: the Construction Command, to build the airfields and base facilities, and the Base K Command, to be responsible for the operation of the base facilities. The former was given three construction areas on eastern Leyte—Tacloban, Palo, and Dulag—in each of which a construction group headquarters was to supervise the work. As many native workers as possible were to be recruited.22

Tacloban was the first field to receive attention; orders were that it was to be improved sufficiently to take a fighter group within five days. The 46th Construction Battalion reached the site on A-day. On narrow, mile-long Cataisan Peninsula, the strip would have to be realigned about 10 degrees if it were to be lengthened eventually to 6,000 feet for bombers; realignment alone would require a considerable additional construction effort. Doing any work on A-day was next to impossible because of the great quantities of supplies and equipment being dumped on the runway from LSTs transferred from Red Beach. Strenuous efforts to get supplies off the runway caused such congestion of traffic at the neck of the peninsula that the engineers could haul little or no coral from the nearby pits, and work on the runway was set back at least two days. On A plus 3 the 1881st Aviation Battalion and part of the 240th Construction Battalion joined the 46th; the three units bivouacked on the peninsula alongside

Laying pierced steel plank (Marston Mat) on Tacloban airstrip

the runway to be near their work, despite the exposed position. They strove to put down a coral base solid enough to support steel mats. By the fifth morning after the landing, the situation was critical. Enemy bombings were frequent; there were about twelve attacks that morning alone. “The sky was notably devoid of our own fighters,” Sturgis wrote, “but Zeros and Bettys were whizzing down from the low overcast like hornets. ...” Rumors were abroad of a giant naval battle off Leyte, as the Japanese fleet made a last desperate gamble to destroy the American task force and drive the Americans from Leyte. Many U.S. planes came in for crash landings; most cracked up on the loose coral and sand of the runway. The pilots explained that their carriers had been sunk or disabled during the battle with a Japanese naval force off the southeast coast of Samar. The engineers dozed some twenty-five wrecked planes into the ocean. That night, between alerts, they worked continuously on the brilliantly lighted runway. By evening of the next day, it was ready for fighters.23

Meanwhile, ASCOM units under Colonel Heiman of the 1112th Construction Group had begun work on the airfields in Central Leyte. The Dulag strip was captured on the second day of the landing; the other three, during the next five days. San Pablo was to be developed into a bomber field; the others were to be improved to take fighters and transports. Men sent out on reconnaissance by Sturgis and Casey reported that work

on the fields, located in the midst of rice paddies and swamps, would be laborious enough during the dry season and well-nigh impossible in wet weather. Supply would be an almost insuperable problem, since the fields were near the one-lane road which ran from Dulag to Burauen and which was already choked with traffic to support the combat units.

Work began first on Dulag. The 808th Aviation Battalion, landing on the morning of 23 October, headed straight for the field, captured two days previously. It was about 300 yards south of the Dulag–Burauen road and parallel to it. The Japanese had hauled gravel in pushcarts from a nearby stream and spread it over the runway to a thickness of about one inch. The 808th, working around the clock, smoothed the runway and built roads to the river to enable trucks to haul gravel.24 Two days later, at about 0930, the men “... were surprised to see a couple of strange looking planes circling the field. ...” They turned out to be Navy fighters, which could not return to their carriers. About fifty planes landed; several cracked up. The dry weather of the next few days made a good deal of progress possible on the runway. On the 27th, the 821st Aviation Battalion joined the 808th. Heavy rains at the end of the month turned the whole area into a sea of mud. The fields in central Leyte could not be made operational within a predictable time.25

The news had come on the morning of the 26th that the Japanese fleet had been defeated. The forces at Tacloban had had a narrow escape; a study of the battle reports indicated that if just one of the Japanese warships, only a short distance away, had sailed into Leyte Gulf, it could have shot up the naval transports and the beachhead and caused incalculable damage. Kenney agreed to take over responsibility from the Navy for air support on A plus 7, even though he had no planes on Leyte because there were no adequate fields on which to base them. He was apparently not greatly concerned since he was already convinced that the Japanese air force could no longer do any serious damage; at the most, it could merely delay the American advance.26 Nevertheless, the lack of American air power on Leyte enabled the Japanese to send in sizable reinforcements via Ormoc, including two complete divisions and parts of three more in the hope of making a decisive stand on the island. In return, the Americans committed the reserve 32nd and 77th Infantry Divisions, the 11th Airborne Division, elements of the 38th Infantry Division, and the 112th Cavalry RCT. Despite the lack of sufficient air cover, the campaign on Leyte developed generally as planned. Enemy opposition was light, although stubborn pockets of resistance developed in some areas. While the Japanese reinforcements did not alter the planned strategy, they did prolong the fighting.27

Combat Engineers—Roads and Bridges

Although the fighting on Leyte was more or less in the nature of a conventional

overland advance, combat support was much like that in New Guinea in that road and bridge construction and maintenance accounted for almost the entire effort. Roads required the most work by far. The island’s thoroughfares disintegrated rapidly under military traffic. To make matters worse, five days after A-day, heavy rains began—the first of the season. In both corps areas, long stretches of road became morasses. During the first three weeks, X Corps had only three combat battalions to maintain roads in the Leyte Valley; they could not cope with the rapid disintegration of the supply routes. The amphibian engineers saved the situation by moving supplies along the northern coast. The combat engineers continued to have trouble with roads in the valley. Since most of the roads were built above the surrounding rice paddies, they were extremely difficult to restore, once they broke down. After the troops got out of the valley, conditions were just as critical. The advance through the mountains from Pinamopoan on northern Leyte to Ormoc came almost to a standstill because of the poor roads. In some places, the troops had to be supplied by air drop or by native carriers because constructing roads into these regions was virtually impossible. The few combat battalions on northern Leyte had to maintain long stretches of supply routes; a single battalion might be responsible for as much as thirty or forty miles. Many routes could not have been kept open had it not been for the help of native workmen. In the XXIV Corps area in central Leyte, the 13th and 321st Engineer Battalions of the 7th and 96th Divisions were especially concerned

with the road leading west from Dulag to Burauen, the main corps supply route. This thoroughfare, which passed through a number of low, swampy areas, required a great deal of corduroy. The constant stream of traffic made any real job of improvement or even maintenance almost impossible. The combat battalions in both parts of the island had an especially heavy burden with regard to road construction because of the insufficient number of corps engineer troops. Some shore party engineers were put on road work in the XXIV Corps area and a number of ASCOM units were sent to both corps, but few such men or units could be spared.28

The main roads on Leyte had about 300 bridges, some 30 of which could be regarded as of critical importance. Were the Japanese to destroy any one of the latter, the main supply routes might be blocked for days. The astonishing thing is that the Japanese left all the principal bridges intact. They did destroy a number of minor structures, most of them built of wood, and guerrillas had wrecked an additional number of smaller spans. Neither Japanese nor guerrillas destroyed bridges in an expert manner; as a rule, they left piers and abutments in place, so that the combat engineers could easily replace most spans with timber trestles. Bailey bridging, scarce on Leyte, was especially valuable in areas of extensive rice paddies, where little timber was available. The 556th Heavy Ponton Battalion was directed to establish a “bridge park” where all

Bailey parts were concentrated. From the miscellaneous tonnages shipped to Leyte, a total of some 600 feet of double-lane Bailey bridging was assembled and distributed as an Army-controlled item.29

Mines, Fortifications, and Obstacles

Japanese mines, fortifications, and obstacles played an insignificant role in the Leyte Campaign. The troops encountered a few antitank obstacles, which were not effective. The enemy had erected no fortifications in any real sense. Mines were found in a number of places, some near the landing beaches. The Japanese had hurriedly mined Tacloban airstrip by burying about 100 bombs with the nose fuses flush with the surface. More mines were found in the interior of Leyte, where the Japanese had time to lay them after the American forces landed. In the central part of the island, a considerable number, including bombs, yardsticks, porcelain, and tape-measure mines, were found along the roads and around the airfields. Too poorly concealed to be effective, they played no appreciable part in the campaign. In a warehouse in Tacloban, the engineers came across a number of coconuts. Each had been cut in half and cleaned out; a grenade with nails fastened to it had been placed inside. Each coconut had then been wired together again, apparently to be booby-trapped so that the grenade would explode when the coconut was picked up. As it was, no use was made of these devices.30

ASCOM—Airfields and Base Construction

Charged with both airfield and base construction, ASCOM had heavy responsibilities. It was the airfields that remained of vital concern. Tacloban was coming along as well as could be expected, but the almost complete lack of progress on the fields in central Leyte was cause for alarm. The heavy rains of late October and early November practically put an end to the work. Casey, after a conference with Sturgis and representatives of Fifth Air Force and GHQ, suggested that better sites be found near the landing beaches, and, if none were acceptable to the air forces, that the construction effort be restricted to Tacloban and Dulag. The air forces insisted on the completion of all four fields in central Leyte, but their wishes could not be met. Bayug and Buri, repaired for dry-weather use, became completely unserviceable soon after the rainy season began, and the roads leading to San Pablo became such impassable sloughs that the field had to be abandoned in mid-November. Dulag finally became operational on 18 November, when 4,1 00 feet of landing mat was in place.31

Colonel Heiman, sector engineer at

Dulag, was firmly of the opinion that meeting the construction deadlines for the fields in central Leyte was out of the question. Shortly before Thanksgiving Day, he met with Generals Kenney and Whitehead at the Dulag strip. They wanted to know when a parallel taxiway would be ready so that a fighter group could use the runway “with facility.” Colonel Heiman later wrote that his reply at the time was, “As long as the rains continue as they have, I can give no estimated dates of completion for the strip, taxiways or hardstands.” Heiman explained to Kenney and Whitehead that even if the weather cleared, progress on the airfield would be slow because engineers would have to be diverted from the airfields to keep the important supply roads open. Heiman had informed Colonel Sturgis about the condition of the roads, and Sturgis had directed that additional engineers be put to work on them. General Kenney pointed out that the plans for the Luzon campaign were in jeopardy, and that he needed a date at least for the completion of the Dulag strip. Heiman thereupon asked Kenney and Whitehead to take a ride with him on the Dulag-Burauen road. It was so bad they could not get through. They were nevertheless very much concerned about the diversion of engineer strength to the road. On Thanksgiving Day, Heiman recommended that plans for constructing facilities at the three strips west of Dulag be abandoned. Most other engineers were of the same opinion and many had already made similar recommendations. Late in November, work on the three western fields was stopped.32

With only two all-weather fields—Tacloban and Dulag—on Leyte, another was urgently needed, even though the Japanese Air Force was no longer the threat it had been. The only desirable sites for additional fields were along the eastern coast. Many miles of flat, sandy beaches extended southward from the Cataisan Peninsula. Eight miles from Tacloban, near the town of Tanauan, was a site, which, from the engineering point of view, was almost ideal. Even in rainy weather construction would not be difficult. From the point of view of the air forces, the area was not very desirable, because any field built there would have the southern end of the runway quite close to a hill some 250 feet high. A further complication was that the site was already occupied by Headquarters, Sixth Army. The engineers nonetheless recommended construction there. General Kenney consented, and General Krueger agreed to move his headquarters. Three aviation battalions began work on 28 November; within two and one half weeks, a fighter runway, 6,000 feet long, surfaced with steel mat, was ready.33

ASCOM engineers were providing numerous additional facilities on Leyte. A serious problem from the first was the allocation of sites.. Because the maps used in planning had been so inadequate, the areas selected were not what had been expected. Two of Sturgis’ engineers, Col. William J. Ely, his executive, and Col. John C. B. Elliott, his operations officer, reconnoitering close behind the advancing infantry, found, in

Sturgis’ words, that “... nearly all of the proposed sites for depots were located in rice paddies and swamps. ... There was very little available space that would not become a quagmire when the rains started. ...”34 The situation was aggravated by the fact that so many major headquarters, all in need of space, moved into Leyte in the first days of the assault, and for the most part encamped on the beachhead. At Sturgis’ suggestion, Krueger organized a board made up of two officers from each major command—its purpose to allocate space. Meanwhile, about twenty officers and men had the job of traveling about in jeeps in search of dry areas.

In order to do the required construction, ASCOM needed large numbers of native workers. Contrary to expectations, they were at first hard to recruit. Many, having acquired ample stocks of food from looted warehouses, were not much interested in working; large numbers were not eager to go to areas likely to be bombed; and many could not work because there was no transportation from their homes. Gradually, and with the help of local government officials and the encouragement of their priests, the natives began to register for employment. By the end of October, 2,500 had been recruited but their usefulness in the early stage of the program was impaired by the high rate of absenteeism.35

The construction of docks had high priority; work was to be completed in sixty days, that is, by 18 December. ASCOM engineers in charge of the project ran into unexpected difficulties. They found that men and materials scheduled for the work had to be diverted to combat areas for road and bridge construction. Also, they encountered unfavorable offshore conditions, such as rock bottoms, precipitous underwater slopes, and, in some places, shallow water. Still, dock and jetty construction completed by late December was impressive. ASCOM had finished a floating and a fixed dock for Libertys and had a second fixed dock about one-third done. Six fixed and four floating lighter jetties were in operation. Construction was continuing. The dredge Raymond arrived in the first days of the operation to deepen Tacloban harbor, but because of a shortage of spare parts, the dredge was of little use until the combat phase of operations was almost over. The Raymond then pumped sand from the harbor bottom to Tacloban airdrome to make up for the shortage of coral.36

ASCOM engineers had many other construction responsibilities. One was to provide storage tanks for gasoline, together with distribution systems at the airfields. At Tacloban, they had in operation by 28 October a temporary system, consisting of a 500-barrel tank on the shore, connected by pipeline with a fuel barge. The permanent system subsequently installed there included storage tanks for 11,250 barrels of aviation gasoline, 5,500 barrels of motor fuel, and 5,500 barrels of diesel fuel, together with pipelines and jetties. At Tanauan, they completed a tank farm with a capacity of 2,000 barrels. Dulag was served by a fuel barge, connected by pipeline with the tank farm at the airfield.

Included among ASCOM’s accomplishments was provision for 13,500 hospital beds in tents. A major job was to widen and keep roads in usable condition; about too miles of thoroughfare were maintained and improved. Some projects fell behind schedule because of too few supplies, a shortage of some kinds of engineer troops, the diversion of others to support the combat forces, and, finally, the heavy rains—thirty-five inches fell in the first forty days, about twice the average amount.37

The End of the Leyte Campaign

The struggle for Leyte, prolonged by the ability of the Japanese to land reinforcements on the west coast near Ormoc, nevertheless moved toward its inevitable end; the enemy was gradually compressed into the western part of the island and destroyed. On 25 December, Sixth Army turned control of operations on Leyte and Samar over to Eighth Army. Organized at Hollandia in September 1944 under General Eichelberger and up to this point engaged in destroying or neutralizing the remnants of the Japanese forces in New Guinea and on nearby islands, Eighth Army was well prepared to participate in more extensive operations in the Philippines. Eighth Army continued mopping-up on Leyte and Samar until May 1945.

Mindoro

As a prelude to the landings on western Luzon, the seizure of the lightly held island of Mindoro and development of airdromes near the city of San Jose on the southwestern coast held a prominent place in early planning. In mid-October MacArthur had directed Sixth Army to seize the San Jose area. The target date was set for 5 December. Company C of the 161st Engineer Parachute Battalion and Company B of the 3rd Combat Battalion were assigned combat missions; a RAAF airfield construction squadron and three engineer aviation battalions had the job of airfield construction. The 532nd Boat and Shore Regiment was to land supplies and equipment. At the beginning of December American land-based air units still had only a precarious hold in the Philippines. Leyte had two operational fields; additional ones were urgently. needed. Sites tentatively selected on Mindoro would be ideal because they were on the western side of the island, at that time of the year in its dry season. Since enemy resistance on Leyte was so stubborn and airfield construction so far behind schedule that adequate air cover for forward operations was impossible, the assault was postponed for ten days.38

On 15 December the landing was made near San Jose without opposition. No preinvasion bombardment was necessary, and the objectives of the initial assault were quickly reached. The building of airfields on Mindoro was easy. On the first day of the landing the engineers began to rehabilitate the two strips near San Jose. Within five days, Hill Field, a 5,700-foot dry-weather runway for fighters, had been completed.

On 28 December, seven days ahead of schedule, the 7,000-foot San Jose dry-weather strip was ready for use. On January Eighth U.S. Army took over operations on Mindoro. Engineer tasks continued. The aviation engineers began work on two additional all-weather fields, which would be needed when the rainy season set in. The fields on Mindoro assured more adequate air support for the planned invasion of Luzon.39 “The success of the work at Tanauan and the ease (logistics not considered) with which the dromes at Mindoro were shaped accelerated the loss of interest in Leyte,” Colonel Heiman wrote later. “By New Years’ 1945, it was evident that Leyte would soon be a backwash.”40

Luzon: The Drive to Manila Tactical

Once Leyte and Mindoro had been secured, Luzon was to be attacked. The struggle for this island would be a crucial one. The plan of campaign for the MIKE series of operations, which were scheduled for Luzon, included a landing at Lingayen Gulf, a drive down the Central Plains toward Manila, seizure of the capital, capture of the fortified islands in Manila Bay, and then a mop-up of the Japanese who had retreated to the outlying parts of Luzon. Probably the most critical part of the campaign would be the drive down the Central Plains. From a military point of view, the plains, with a maximum width of 40 miles and extending 00 miles from Lingayen Gulf to Manila, were the most vulnerable part of the predominantly mountainous island. It was down them that the Japanese had launched their major attack in 1941. The campaign of 1945 would be the campaign of 1941 in reverse, with the Americans the attackers and the Japanese the defenders. The initial assault, the drive down the Central Plains and the capture of Manila—the M-1 operation—was to be the responsibility of two corps: I Corps, with the 6th and 43rd Infantry Divisions, and XIV Corps, with the 37th and 40th Infantry Divisions. The 158th Regimental Combat Team, the 13th Armored Group, and the 6th Ranger Infantry Battalion were to provide additional support as needed. In reserve were to be the 25th Division and the 1st Cavalry Division. The Luzon operation was at first scheduled to begin on 20 February 1945, but the date for the landing was later moved forward to 20 December 1944, and then back to 9 January.41

Engineer Planning: Sixth Army and ASCOM

Engineer long-range planning required for M-1, the most extensive overland campaign in the Southwest Pacific, in which some 250,000 men were to be engaged, was considerable. Every possible angle of terrain intelligence had to be

studied; maps, and especially aerial photographs, had to be scrutinized with great care. The fact that the Philippines had been an American possession was a decided advantage. But almost all the engineers who had firsthand knowledge of the terrain of Luzon were prisoners of the Japanese. Except for Casey, Sturgis, and a few others who had served in the Philippines before the war, Luzon was unknown country to the men who had to plan and prepare for the coming drive to Manila.

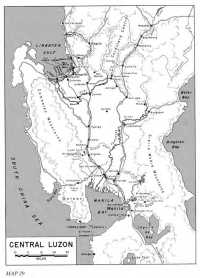

Members of the Engineer Section, Sixth Army, assisted by a number of men from Col. Orville E. Walsh’s 5202nd Construction Brigade, began preliminary planning on 19 September for a landing at Lingayen Gulf and a drive down the Central Plains. A study of the Lingayen Gulf area indicated that the best beaches by far were on the eastern shore to the south of San Fernando. But behind them was a narrow coastal plain, and, in back of it, stood precipitous mountains. (Map 29.) Not only could that part of the gulf be easily defended, but also an invading force would have great difficulty in maneuvering on the plain, which at its southern end narrowed to a width of less than a mile. Farther south, near the town of San Fabian, the beaches appeared to be less desirable but still fairly adequate. LSTs could probably make dry landings at a number of points. Southwest of San Fabian, the beaches were poor. Aerial photographs showed waves breaking from 300 to 500 feet from shore, indicating either that shoals existed or that the surf was heavy. The western shores of Lingayen Gulf could not be considered as possible sites because of reefs, poor beaches, and rocky terrain close to shore. All things considered, the most favorable landing area, from the tactical point of view, included that part of the gulf which stretched from San Fabian to the mouth of the Agno River. The beaches had drawbacks, but these were more than offset by the fact that intelligence information indicated the Japanese would probably offer little resistance to a landing made there, whereas they would almost certainly make a determined stand along the eastern shores of the gulf.42

For the engineers, the plan of assault had advantages and disadvantages. The beaches from San Fabian to the mouth of the Agno, the most favorable from the tactical point of view, had decided drawbacks, the most serious of which were shallow water and heavy surf. The terrain in back of the shoreline was hardly more promising. Inland, for a distance of from two to five miles, were meandering rivers, tidal estuaries, rice paddies, fish ponds, and swamps. But once past these hindrances and on dry ground, an invading force would encounter few natural obstacles on the way to Manila. On the western side of the central Luzon range, the Central Plains had their dry season from November to mid-May. The engineers would not have to contend with excessive rains as on Leyte; if anything, dust would be a nuisance. Lines of communications, while not plentiful, were probably adequate. Highway 3, a two-lane, all-weather road, partly concrete and partly asphalt, as well as a number of one-lane, dry-weather, graveled roads, led from the gulf to the

Map 29: Central Luzon

capital. While these thoroughfares undoubtedly had deteriorated during the Japanese occupation, they could probably still take military traffic. Some twenty-five airfields were in the Central Plains, but only one—Clark Field—had well-developed runways; the others were landing strips with little or no surfacing, and on the whole, were suitable for dry-weather use only. Like the Japanese in 194i , the Americans would have to cross two large rivers—the Agno, flowing into Lingayen Gulf, and the Pampanga, which emptied into Manila Bay. The remaining streams in the plains could probably be fairly easily forded at a number of places during the dry season, especially if the campaign began after the season was well along. On the whole, the plains would probably present fewer natural obstacles to the U.S. Army with its superior equipment than they had to the Japanese.43

While combat engineer requirements would probably not be unusually heavy, a major concern for the first time—more so than for Leyte—was bridging. Two problems loomed: how to get the Army across the numerous water barriers in back of the beaches, especially in the western half of the assault area; and how to get the troops across the principal rivers farther down in the Central Plains. How many bridges would be intact or but slightly damaged was uncertain. If Japanese demolitions were as inept as heretofore, numerous structures would probably still be serviceable or could be quickly repaired; however, it was known that many spans wrecked in the retreat in the last weeks of 1941 had not been restored and that some of those rebuilt could not carry more than 10-ton loads. It could also he assumed that quite a few spans still intact would be destroyed by U.S. bombers before the assault landings at Lingayen Gulf began.44

Sturgis was especially concerned over the shortage of bridging units and equipment. He still had only the heavy ponton battalion and the three light ponton companies which had been on hand for the Leyte operation. Urgently needed were additional units, including at least one with treadway bridge equipment. Since indications were that the number of bridging units would be too small, Sturgis planned to make intensive use of what was likely to be available. To cross rivers which emptied into Lingayen Gulf, infantry support rafts and LCMs would be used as ferries. In addition, the Engineer, Sixth Army, planned to have the decks of all cargo ships loaded with Navy ponton cubes, to be assembled, if necessary, into 240-foot rafts. Each engineer battalion, combat as well as construction, was to have 150 feet of double-lane Bailey and 200 feet of timber trestle bridging, both types combat-loaded. As Sixth Army advanced down the Central Plains, repeated use was to be made of the floating bridges on hand. Sturgis planned to replace them with semi-permanent structures as soon as possible and leap frog the floating equipment forward. This would mean constructing fixed bridges

in “half the usual minimum time.” Sturgis believed this procedure would serve to get the Army across the Agno, but thereafter engineer units would be under considerable strain to replace floating bridges with semi-permanent bridging fast enough to keep up with the advancing infantry. Matters would become especially critical when the troops reached the Pampanga and the major rivers beyond it; a severe shortage of floating bridging might easily develop. Sturgis asked Krueger to request more bridging units from the United States. Sixth Army engineer plans called for one light ponton company assigned to each corps and one heavy ponton battalion, together with one light ponton and one treadway bridge company, assigned to army; eventually, more units would be needed. MacArthur requested additional units, but it was realized the chances were they would not arrive for three or four months and then perhaps without their equipment. The insufficient number of bridging units and equipment, the delay in airfield construction on Leyte, and the Navy’s request for more time to make preparations were the principal reasons for the postponement of M-1 from 20 December to 9 January.45

ASCOM began planning for M-1 at Hollandia on 25 September, when a number of Leyte planners were reassigned to the new operation. They were scheduled to remain at Hollandia, in order to continue work on M-1 after the rest of ASCOM left for Leyte. General Casey directed that planning was “… to conform generally” with that “employed for the K-2 operation. ...” On 6 October ASCOM sent Sixth Army a “tentative plan outlining [ASCOM] responsibilities in the operation.”46 Sixth Army approved it with slight modifications. Thereafter, planning was largely a matter of filling in the details. ASCOM was to be responsible at Lingayen Gulf for the construction of Base M, which was to support the drive of the combat forces to Manila. The base’s operations would be of short duration; after the capital city was taken, a more permanent base would be built in the Manila Bay area.47

A question arose with regard to the 52 02nd Construction Brigade. Casey wanted it assigned to ASCOM, as the 520 st had been on Leyte; Sturgis believed it would be advantageous to have the brigade with its numerous construction units assigned to army, so that it could be used in direct support of a rapid drive on Manila. Since Base M, in any event, was soon to be superseded by the Manila base, construction requirements for the former would probably not be so extensive as for Base K on Leyte. Asked to decide the matter, Krueger placed the 5202nd under army.48 With the Japanese Air Force already in a seriously weakened condition, airfield requirements, in particular, were less. On Leyte, ASCOM had been charged with building four all-weather fields. At Lingayen, it was to have a temporary runway, 5,000 feet long, ready six days after the landing, and it was to have two

all-weather strips finished in fifteen days. Dock construction requirements, likewise, were less than on Leyte. Because needs were less, ASCOM’s organization for M–1 was smaller than for K-2 and it had fewer engineer units assigned to it. ASCOM had fifteen aviation battalions for Leyte, but only nine for Lingayen Gulf. Still, the number of aviation battalions available for M-1 was no less than for K-2, since the battalions ASCOM lost had come under Sixth Army control along with the 5202nd Construction Brigade.49

Engineer amphibious operations at Lingayen Gulf were to be the most extensive so far carried out in the Southwest Pacific. They were assigned to the 4th Special Brigade, which was reinforced with two boat and shore regiments from the 3rd Brigade. Each boat and shore regiment, supporting one division or independent regimental combat team, was to function under the direct control of the unit to which it was attached. The amphibian engineers made arrangements with the Navy for the shipment of engineer landing craft aboard assault vessels to the target area for arrival on S-day; 69 craft were allotted to I Corps, 84 to XIV Corps, and 25 to the 25th Division and other units of the reinforcement group. During the landings, Colonel Hutchings, commander of the 4th ESB, was to act as a special staff officer to General Krueger and as such was to be mainly responsible for keeping a close check on unloading operations and apportioning landing craft to the beaches in such a way that the discharge of cargo would be expedited to the greatest degree possible.50

Assault

The assault was made as planned on 9 January at Lingayen Gulf on a series of beaches fifteen miles long. The 37th and 40th Divisions of XIV Corps landed on the right; the 6th and 43rd Divisions of I Corps on the left. The remaining units of the attacking force, standing by, were to come ashore within the next few days. As the troops in their landing craft neared shore, there was singularly little enemy opposition—only sporadic artillery fire and occasional aerial attacks. Sturgis, aboard one of the vessels of the convoy, saw only two enemy aircraft, one at dusk on S-day, making an unsuccessful suicide attack on the landing fleet, and another two days later, engaged in reconnaissance.51

Amphibious Operations

As planned, the amphibian engineers landed troops of XIV Corps on the right. The 544th EBSR, supporting the 37th Division, brought its first infantrymen ashore at H plus to at Yellow Beach, farthest to the east in the XIV Corps area. The weather was fair, but the seas were rough and the beaches poor. Thirty-five feet in back of the low water line was a dune up to ten feet high,

which made the construction of roads inland difficult. On the second day, the seas became so heavy that a number of LCVPs were broached and the unloading of landing craft became almost impossible. The beach was so unsatisfactory that a new one had to be found; after some reconnoitering, the 544th discovered a likely site along the banks of the nearby Dagupan River and transferred its unloading operations to that point.52

To the west was Orange Beach. Here the 594th EBSR landed the 40th DivIsion. Some random rifle fire was received from the shore and during the first night several air raids occurred in the course of which enemy planes dropped a few bombs. More hampering than the enemy was the surf. LSTs could get no closer than 200 feet from shore. Causeways of ponton cubes placed from the LSTs to the beach made dry landings possible, but the seas became so rough that the causeways could not be kept in place. Orange Beach was abandoned and the 594th sent its landing craft to discharge cargo along the banks of the Calmay River, which paralleled the coast about two miles inland. On the far right of the XIV Corps landing area was Green Beach, which was reserved for service units and the unloading of bulk cargo such as landing mat. On the second day two companies of the 594th came ashore and began unloading LCMs and LCVPs, but shallow water made the job hard. The amphibian engineers at this beach were handicapped by their lack of ponton cubes for causeways and bulldozers for the building of ramps.53

In the I Corps area, the problems were of a somewhat different nature; the surf was not so high, but the water, in most places, was too shallow for satisfactory unloading. On the right were Blue Beaches and 2. Here the 543rd EBSR brought in the 6th Division. The Japanese at first did nothing to oppose the landing except to put some ineffectual rifle fire on the beach. Shallow water prevented LCMs from coming close to land; most were grounded about 300 feet offshore. The Japanese Air Force went into action and strafed the beach, inflicting some casualties among the amphibian engineers. On the second day the seas became rough, with waves up to six feet high, and many landing craft floundered. During the succeeding days, as the surf subsided, supplies could be brought ashore in large quantities.

To the left, at White Beaches 1, 2, and 3, the 533rd and 543rd ESBRs found landing conditions favorable except on the right. Attempts to land LSTs and LSMs here were futile because of the shallow water and fairly heavy surf. Unloading had to be shifted to the left part of the beach. Japanese resistance was more in evidence at the White Beaches. On the first day a number of boats were hit by mortar shells, and during the following days the enemy laid down mortar and 75-mm. and 240-mm. artillery fire, in the course of which the

shore party suffered a number of casualties. Because of the rough seas in the XIV Corps area and at the Blue Beaches, a considerable amount of shipping was diverted to the White Beaches. Some confusion and delays resulted, but not of sufficient importance to affect subsequent operations.54

The amphibian engineers assisted in the landing of one additional unit. On the far left, the shore battalion of the 534th EBSR helped bring in the 158th RCT on Red Beach on S plus 2. The Japanese offered more resistance here than on any of the other beaches, placing heavy artillery fire on the men coming ashore, and causing numerous casualties. The enemy also used small suicide boats filled with explosives, but these did little damage. The 25th Division, the 13th Armored Group, and the 6th Ranger Battalion came ashore on White and Blue Beaches on S plus 2 in landing craft operated by the Navy.55

On the whole, enemy opposition had been surprisingly light. The amphibian engineers had fewer casualties than had been the case at Leyte, Biak, or Wakde. Japanese air strength was noticeably weak—the high surf and shallow water gave the most trouble. In the days after the first landings, the amphibian engineers continued unloading supplies and gave increasing support to the logistical development of the Lingayen Gulf area. They helped construct unloading facilities and built roads and supply dumps. They extended the scale of these activities when they passed from the control of corps and divisions to ASCOM on 19 January.56

Combat Engineer Support

In the egress from the beaches and the subsequent drive down the Central Plains, combat engineer support was furnished by the divisional combat battalions and by engineer units assigned to the two corps and to the 5202nd Engineer Construction Brigade under Sixth Army. Five divisions, an RCT, and an armored group took part in the initial advance. XIV Corps with the 37th and 40th Divisions was on the right; I Corps with the 6th, 43rd, and 25th Divisions, the 158th Regimental Combat Team, and the 13th Armored Group was on the left. XIV Corps, scheduled to advance directly on Manila, was to bear the brunt of the drive. I Corps, responsible for protecting the left flank, was to drive across the island in a southeasterly direction toward Dingalan Bay. General Krueger believed that the Japanese, having expected a landing on the eastern shores of Lingayen Gulf, would have strong positions in the mountains to the northeast of the Central Plains, a view already partly substantiated by enemy interference with the landings on the far left, and to be still further substantiated by the stubborn resistance which I Corps was to meet in a number of places as it drove ahead. Krueger’s great concern was that XIV Corps should not advance so rapidly in the face of comparatively light resistance that it would outrun its

supply lines or expose itself to a flank attack.57

On the far right, the 40th Division, supported by the 115th Combat Battalion, was scheduled to advance south from Lingayen Gulf to Highway 13 and thence to Highway 3, which led directly into Manila. Resistance to the landing was completely lacking. The movement from the beach was easy; the combat engineers broke down a bank, about three feet high, beyond which roads led to the town of Lingayen, where the streets, but slightly damaged, easily carried military traffic. Within a distance of two miles south of the town, two major rivers had to be crossed—the Calmay and the Agno; the bridges over both had been destroyed. The combat engineers took the troops over in assault boat ferries constructed by Companies A and B and in landing craft borrowed from the 594th EBSR. Within three days most of the division was across the Agno and advancing down Highway 13. Great expanses of wet rice paddies forced the troops to stay close to the road. Since smaller bridges, though usually intact, could seldom take more than 3-ton loads safely, the 115th engineers strengthened them to take thirty-five tons. Only one large bridge on Highway 13—at San Clemente—was completely destroyed. On Highway 3, a most important bridge—the one over the Tarlac River—had twenty spans, two of which were partly demolished; they were repaired in two hours. Complete destruction of this bridge would have seriously slowed the division. Within two weeks the 40th Division had reached the town of Barnban, sixty miles from Lingayen Gulf and somewhat more than halfway to Manila.58

On the left in the XIV Corps area, the 117th Combat Battalion supported the 37th Division in its drive southeast from Lingayen Gulf to Highway 3. The first major obstacle again was the Calmay, about a mile south of the landing area. The river did not prove the hindrance it might have been. The bridge which the division was to use, some 600 feet long, had 3 spans of 150 feet each and one span of 120 feet, the latter on the near shore. The first troops to reach the site found the Japanese had destroyed the 120-foot span but had left the other 3 intact. The combat engineers on 13 January easily replaced the missing span with a Bailey bridge. The 37th Division was scheduled to cross the Agno some twelve miles to the south at Bayambang, where the 300-foot railroad bridge over the river was only slightly damaged. The engineers on 14 January repaired the piers and placed decking on the bridge so that it could take 15-ton wheeled traffic. Two days later the 117th battalion constructed a ponton bridge capable of taking 13-ton loads. During the night of 15 January seventeen men of the 530th Light Ponton Company and twenty-five men of the 117th engineers put a ponton bridge to take 8-ton traffic across the Agno at Wawa. Construction was difficult; the men had no time for a reconnaissance, and it turned out that a sandbar in the

middle of the river forced the engineers to put up two bridges.

From the Agno to the Pampanga, bridging for the 37th Division was fairly easy. The troops used fords extensively. Where necessary, the combat engineers, using local material, repaired or constructed timber trestle spans to carry loads up to sixteen tons; this work, they reported, constituted up to 75 percent of their effort during the first two weeks. The men built some bridges at night, using lights, sometimes as much as ten miles ahead of the main line of resistance, and without infantry protection. Very little effort was required on roads. Highway 3 had many holes but was usable for all military traffic. The combat engineers expended time and effort on developing a two-lane graveled road east of Highway 3 into a parallel secondary route.59

It was much the same story in the I Corps area. The 6th Combat Battalion, supporting the 6th Division in its advance from the beaches to the town of Urdaneta on Highway 3, had no trouble at first, even though, as maps and aerial photographs had correctly indicated, the beachhead was something of an island. To the south was the Binloc River, lined with fish ponds, to the east the Bued, to the west the Dagupan. LVTs carried the assault troops across the waterways. For the supply and support of the troops the 6th engineers had to bridge the rivers in the line of the advance. They constructed a 150-foot Bailey across the Binloc, a major problem being the marshy gr, ound near the river’s banks. The next big job was getting the troops across the Agno on Highway 3 near Carmen. Here was the bridge of thirteen spans, each 160 feet long, one of which the retreating American and Filipino forces had demolished during the withdrawal of 1941. The Japanese had replaced the destroyed span with a timber structure; American bombers sweeping over Luzon before the Lingayen Gulf landing had destroyed more or less completely four of the concrete spans. To get the first troops across the river, the engineers hired about 250 Filipinos to build bamboo rafts; the natives put 70 together, but none were needed Because the Japanese did not oppose the crossing. The 506th Light Ponton Company and one platoon of the 6th engineers got the job of putting a ponton bridge across the river and preparing the approach roads. Before construction began, Japanese forces reached the opposite bank and held up work for about twenty hours. As at Wawa, a sandbar in the middle of the river bed required the men to build two floating bridges. The advance elements of the 6th Division crossed over on 20 January. Beyond the Agno, the most important jobs were improving and maintaining the roads as far as the towns of Guimba and Cabanatuan.60

Farther to the east, the 118th Combat Battalion of the 43rd Division reported that it had little trouble. The roads from the beach crossing swamps and ponds were “intact.” Farther inland, the main roads were in “excellent condition.” The bridges were too flimsy to take division loads, but railroad bridges

and embankments, almost everywhere in excellent shape, were quickly prepared to take all traffic, and fords were easily found. The engineers had no difficulty developing and maintaining an adequate, even if heavily traveled, road net. The men, called upon to destroy occasional obstacles such as pillboxes and barbed wire entanglements, some of them mined and booby-trapped, dealt with them handily. Sometimes enemy infiltrators tried to disrupt work by planting mines at the job sites. “The Japs would come in at night and lay a few mines at random on a portion of road just constructed and aside from the harassing effect accomplished little,” the 118th reported.61

On the far left were the 65th Combat Battalion, supporting the 25th Division, and the 186th Combat Battalion, supporting the 13th Armored Group; both combat battalions landed on S plus 2. The 158th RCT, which came ashore the same day, had no engineer unit. The 65th engineers were active in the San Manuel–Santa Maria–Umingan area at the northeast edge of the Central Plains. They developed about 100 miles of new roads and trails and strengthened about fifteen timber bridges. The men spanned the Agno, no more than a small stream in this area, with an infantry support bridge 150 feet long and prepared a ford 400 feet wide nearby for heavier loads. Since fords were readily found at all streams, road maintenance was a far more time-consuming task than bridging.62

The 186th engineers, in landing, encountered more opposition from the Japanese than any other combat battalion. The unit came ashore at 1830 on 11 January; about 8 hours later the enemy began shelling the ships as the troops were unloading them. Six men of the 186th were killed and two wounded; enemy fire was so heavy that unloading had to be postponed till morning. Since the 13th Armored Group moved into bivouac, the 186th engineers had no immediate combat missions. They improved and maintained some roads near their bivouac area and spanned a nearby stream with a Bailey bridge.63

The combat battalions had an additional construction task which at times was of considerable importance—the building of temporary landing strips needed by artillery liaison planes for courier service and by transports for the evacuation of casualties. The men prepared most of these strips with bulldozers. Since the Central Plains had many level, cleared areas, little earth-moving was required. Large expanses of dry rice paddies offered the best sites. In a short time, the troops leveled off irrigation dikes and prepared a smooth surface. “Dry weather airdromes across rice paddies,” Sturgis wrote to Somervell, “was the easiest thing that we have had fall in our lap in the last two years.. ..”64

Mines and Obstacles

The troops found few mines at the beaches or on the routes leading inland to the main highways of the Central

Plains. No units except the 118th engineers reported encountering any in quantities. It was only after the troops had advanced far down the Central Plains that they ran into fairly large numbers of mines in some areas. Quite a few were found near Clark Field and Fort Stotsenburg. At Clark, the 117th engineers had to deal with approximately 1,300 buried aerial bombs, buried just deep enough to put the nose fuse even with the ground. Locating these mines was easy; not only were the shipping boxes scattered about in the mined area but also the plugs were on the ground nearby. In a few instances, the mined areas were covered by enemy fire. In that event, the Infantry-Engineer-tank teams went into action. Fire from the infantry and tanks covered the engineers probing for mines. The men, as a rule, disarmed the aerial bombs by hand. They turned down the arming collar on the fuse spindle, unscrewed the nose fuse, and inserted the bomb plug in the nose-well. Using an A-frame or truck winch, they pulled the bomb out of the ground. In the few cases where the detonators were jammed, the bombs were blown in place with explosives. Troops in the foothills on the east side of the Central Plains found a number of mines, including artillery shells, flower pot and tape measure mines, and some improvised box mines made of wood or tin. None were placed in any identifiable pattern, and most were so poorly camouflaged that they were easily detected.65

The combat troops ran into only a few roadblocks or similar obstacles, and most of these, almost invariably consisting of logs or wrecked equipment, had been hastily put in place. Some machine gun emplacements covering strategic road intersections or bridges had been constructed, but they were not manned. On the whole, the obstacles encountered on the Central Plains were ineffectual. In the hills west of Fort Stotsenburg, the Japanese had built well-entrenched positions. They had constructed elaborate defensive installations, including caves, many of them blasted in vertical cliffs and interconnected by tunnels. These positions were extremely difficult to reduce. Since they were located on the flank of the route to Manila, they had more of a nuisance value than anything else and did not slow down the advance to the capital.66

ASCOM

The first elements of ASCOM came ashore on S plus 1. General Casey, scheduled to land on S-day, was delayed until the next afternoon because the destroyer on which he was aboard had to escort a crippled transport. Upon landing, he went to Lingayen airstrip, situated between the town of Lingayen and the sea, where he met Col. Reginald L. Dean, chief of ASCOM’s Construction Section. Aircraft carrier support was to be withdrawn seven days after the first troops hit the beach; this meant an airfield would have to be ready within 5

days; immediately required was a 5,000 foot runway.67

Special efforts had been made to prevent the confusion that had arisen at Tacloban, where the thousands of tons of supplies dumped on the runway had made rapid rehabilitation of the airstrip impossible. Kenney had prevailed on MacArthur to call a special conference shortly before the convoy set sail from Leyte for Lingayen Gulf. Among those present were Kenney, Krueger, Casey, and Sturgis. The conferees agreed that three fast supply ships loaded with steel mat were to accompany the assault echelon and land as close to Lingayen airstrip as possible on S-day, that one construction battalion scheduled to land on White Beach 2 was to be shifted to Orange Beach near the airstrip, that a group of ASCOM engineers assigned to the leading assault wave was to go at once to Lingayen airfield and stake out the construction area, and, finally, that the commanding general of XIV Corps was to see to it that troops, vehicles, and supplies were kept away. These arrangements were for the most part being carried out. However, landing conditions, the nature of the soil at the airstrip, and the degree of enemy resistance that might develop were unknown factors; how rapidly construction would progress was, at least partially, dependent on them. If soil conditions were not satisfactory, four additional days might be needed to make the strip operational.68