Chapter XV: The Final Months of the War

During the last months of the war, the Allied forces made great strides both in driving toward the Japanese home islands and in liquidating the Japanese conquests made earlier in the war. The destruction of organized resistance in the Philippines and Borneo all but severed the Japanese lines of communication to the East Indies and southeast Asia, while the capture of the islands of Iwo Jima and Okinawa, so close to Japan itself, put the Empire in gravest danger. In southern China, the Japanese forces, which had advanced threateningly in 1944, were, by the spring of 1945, in full retreat. While enemy forces were being destroyed or were in retreat on the islands of the Pacific and on the Asian mainland, the more remote bases were being dismantled and closed out, but an enormous amount of base and airfield construction was still under way, particularly in the Philippines and on Okinawa, for the purpose of supporting an invasion of Japan proper. At the same time, plans and preparations were being made for the invasion itself.

Destruction of the Japanese in the Philippines and Borneo

Overall Plans

Since the Philippines, particularly Luzon, were to constitute the most important base area to support the coming invasion of Japan, the enemy forces on those islands had to be destroyed or rendered harmless. No time was lost in getting on with the job. While Manila and Corregidor were still under attack, operations were begun against the Japanese who had withdrawn into the outlying parts of Luzon as well as against those still more or less in control of the central and southern islands of the archipelago. On 5 February 1945 MacArthur directed Sixth Army to destroy the Japanese in northern, eastern, and southern Luzon. The next day, he directed Eighth Army to seize certain islands in the central and southern Philippines.

Sixth Army’s plan of campaign on Luzon called for the destruction of the enemy by three corps. I Corps would have the mission of capturing Baguio and securing the Cagayan Valley, with the city of Aparri, on Luzon’s northern coast. XIV Corps was to begin the task of destroying the Japanese in the Sierra Madre mountains of east central Luzon. After the first few weeks, XI Corps was to take over this mission, while XIV Corps attacked the Japanese in the southern and southeastern parts of the island. Eighth Army’s operations in the central and southern Philippines, to be known as the VICTOR operations, were to be amphibious assaults. The first would

be directed against the southwestern islands—Palawan, the Zamboanga peninsula of Mindanao, and the Sulu Archipelago. Thereafter, four of the major islands in the central Philippines—Panay, Negros, Cebu, and Bohol—were to come under attack. These four were part of the Visayan group of islands, two of which—Leyte and Samar—were already under American control. Lastly, the Japanese in the main part of Mindanao would be crushed. Thereupon, the Philippines would be completely under American control.1

Engineer Planning

Sixth and Eighth Army engineers began planning after receiving MacArthur’s directives. Sturgis’ engineer section made a study of the terrain of the more remote parts of Luzon and the highways and trails leading to them. Unlike the amphibious operations along the New Guinea coast or the advance down the Central Plains, the drives into the outlying parts of the island would be, for the most part, through mountainous terrain. After making extensive reconnaissances from the air and on the ground, Sixth Army engineers were convinced that their most important task was the construction and maintenance of roads. Bridging would probably not be a major job until the onset of the rains in May. Japanese mine fields and demolitions would very likely be as crude as before, but in the mountainous parts of the island might be considerably more effective in holding up an advance. Engineer work, unlike that performed in New Guinea, would, as a rule, be done in the conventional manner. Troops under corps and army would undertake major construction in back of and not at the front lines. Since there were not enough engineer units or supplies to support three simultaneous actions in widely separated areas, General Sturgis decided to keep most of his heavy construction troops under army control in or near Manila until developments showed where they could be used to best advantage.2

Meanwhile, Eighth Army engineers under Col. David M. Dunne were deep in plans and preparations for the VICTOR operations, of which there were to be five. The various islands of the central and southern Philippines had similar terrain—a narrow coastal belt behind which rose steep and wooded mountains. There was little time for reconnaissance, and map coverage was inadequate. Since the attacks were to be amphibious, they would undoubtedly be carried on in the same manner as the earlier similar operations along the New Guinea coast. Heavy naval and air bombardments would drive the enemy away from the beaches and into the interior of the islands so that, soon after the initial landings, the engineers could begin work on bases and airfields virtually unhampered. The Eighth Army engineers, in making tentative plans for construction in each area, had to devote considerable effort to getting sufficient numbers of troops and adequate amounts of supplies. The relatively few units

available were so apportioned that each operation would have amphibian and combat units and either aviation or construction battalions.3

East Central Luzon

On Luzon the first attack began on 20 February when the st Cavalry Division and the 6th Infantry Division of XIV Corps launched an assault against the Japanese who had retreated into the Sierra Madre Mountains in the east Central part of the island. In this rugged and inhospitable region, where roads were few, the terrain greatly favored the defenders. Here the Japanese had under their control Ipo Dam, and ten miles to the southwest, Montalban Dam, two important elements of Manila’s water supply system which had to be captured intact, if possible. The engineers were in continual demand to support the infantry in the drive through the mountains. Tasks of the 8th Engineer Squadron and the 6th Combat Battalion were similar. Mines were numerous along the narrow and primitive roads. In many places, the Japanese had set up roadblocks and covered them with fire. Some were of the abatis type; others were blasted out of the steep slopes on both sides of the road or path. Engineer demolition teams helped destroy caves, bunkers, and pillboxes in which the enemy were hiding. A major task was building and maintaining roads. Often the infantry had to wait until the engineers could fashion a trail. Steep grades, large outcroppings of rock, and enemy fire all slowed down construction. Maintenance of the roads, most of them unsurfaced and rough, was complicated by the constant traffic.4

Northern Luzon

The attack against the Japanese on northern Luzon began on 21 February. By that date, I Corps held a line across the narrow waist of the island from Damortis on Lingayen Gulf in the west to Baler Bay in the east. The Cagayan Valley, a major food-producing area, stretched more than 200 miles to Aparri. Bounded on the east, west, and south by broad and rugged mountain ranges, it had two approaches from the south feasible for military operations: one from Bambang; the other from Baguio, fifty miles to the west. Bambang could be reached by two routes. One was by way of Highway 5 running from San Jose, at the edge of the Central Plains, up the Tulavera River valley to Balete Pass. The enemy positions at the pass were considered the key to the southern defenses of the Cagayan Valley. Once they were taken, the forward movement down the valley would be relatively easy. Another possible route was by way of the Villa Verde Trail, a path for foot travelers and carabao, which began to twist through the mountains 25 miles west of Highway 5 and joined it just north of Balete Pass. Baguio had four approaches. Highway 11, also known as the Kennon Road, was the most direct. From Rosario it ran northeast and then north through the Cordillera Central

Mountains. A longer route was by way of coastal Highway 3 and then inland by way of Highway 9. Two trails to Baguio cut through the rough triangle formed by the three roads. From Baguio, dirt roads and trails led eastward through the Cordilleras to the Cagayan Valley. The 25th and 32nd Infantry Divisions were to take Bambang; the 33rd Infantry Division was to capture Baguio and then assist the other two in the drive up the Cagayan Valley. Progress of the drives through the mountainous terrain of northern Luzon would depend in large measure on the success of the engineers in overcoming natural and man-made obstacles.5

The Advance to Barn bang

The 25th Division, with its 65th Combat Battalion, moving north from San Jose along Highway 5, got off to a good start. By mid-March, that is, in about three weeks, it was nearing Balete Pass. The engineers kept pace with the infantry, developing the highway, a two-lane graveled road, as the main supply route for the division. Most of the men were engaged in repairing and reinforcing bridges. They cleared three mine fields and spent much time probing for additional mines which the enemy had scattered about in haphazard fashion. Just to the south of Balete Pass, the road ran through a deep defile. The nearer the troops approached the pass, the greater became the enemy’s resistance. Since a frontal attack would be costly, the engineers had to put in numerous side roads through the rocky terrain to make possible flank attacks on enemy positions. Because the roads would be abandoned after the troops had won the area, bridges were not put in; the engineers either found fords or constructed temporary crossings of steel culverts. The men had to be continually on the alert for mines. It was standard practice for the enemy to sneak back and replant an area previously cleared.6

The Villa Verde Trail

When the 25th Division began its drive toward Bambang, the 32nd Division with its 114th Combat Battalion was at the lower end of the Villa Verde Trail at Santa Maria. The infantry was to advance along the trail; at the same time the 114th engineers were to transform the pathway into a combat road. Winding some 25 miles through mountains and over hogback ridges and reaching an elevation of 4,800 feet, the trail connected two points only 11 miles apart by air. The surface was hard-packed clay. Because fairly rapid construction was necessary, the engineers decided to dispense with some of the basic principles of road building. In widening the footpath, which in places clung to the sides of the steep hills, the men began cutting from the bottom of a hill instead of the top. The overhangs sometimes caved in, burying equipment. Dozers, slipping over the precipitous slopes, went down as much as 400 feet and could be recovered only with difficulty; in a number of instances, roads had to be built to

them to get them back on the trail. Although the infantrymen were well ahead of the engineers most of the time, the enemy infiltrated the rear areas on several occasions. At Kilometer 19, one of the dozers came under enemy fire; eighteen 47-mm. shells landed near the machine. Shell fragments tore many holes in the blade and body of the dozer, but caused no casualties.

On 5 March the infantry reached Salacsac Pass, where the Villa Verde Trail turned east toward Santa Fe and Highway 5. The Japanese, waiting there, made determined efforts to halt the advance; enemy machine gun fire was so heavy that no progress could be made for days. The Japanese had built numerous caves in the pass area. The engineers brought up armored dozers to prepare firing positions for tanks. Protected by their cabs, the men kept on working despite minor wounds received from bullets that found their way through the portholes. One armored dozer, working its way around a bend, ran into fire from a machine gun about twenty feet away. The operator, slightly wounded, charged the gun with his dozer. The bullets cut the cable and dropped the blade. The operator withdrew to make way for a tank, which proceeded to destroy the machine gun. The cable was quickly repaired and the bulldozer operator resumed work in forty-five minutes. The next day he buried three Japanese in caves. On the whole, working with armored dozers on the precipitous slopes of the Villa Verde Trail was dangerous because the visibility of the operators was so severely restricted. While the infantry vainly attempted to get control of Salacsac Pass, the 114th engineers continued to push forward slowly on the road and to improve the part to the rear. Dreary weeks passed while the enemy continued to hold at the pass.7

The Drive to Baguio

Meanwhile, during the first part of March, the 33rd Division was advancing on Baguio. Here, also, the work of the 108th Engineer Combat Battalion was largely road construction, but, as elsewhere, many other jobs had to be done. The Japanese had placed numerous mine fields, most of them poorly camouflaged and some so hastily laid that they were wholly ineffective. Still, the combat engineers could not take any chances and cleared twenty-five fields. The Japanese, in retreating, had destroyed most of the bridges. Wherever possible, the engineers located fords or repaired the ruined structures, salvaging such materials as they could. At one point on the Kennon Road, the Japanese had destroyed an 80-foot span over a gorge forty feet deep. The site was at a horseshoe bend, with sheer cliffs on one side, where only a 30-foot horizontal clearance at the abutment was left in which to maneuver. Instead of the usual two hours, the men needed sixteen to swing a Bailey into place.

One of the urgent missions of the 108th engineers was to seize intact the two concrete and steel bridges across the

Trucks negotiate the Villa Verde trail where engineer construction is in progress

Bauang River near its mouth on the west coast of Luzon. The two spans had to be taken undamaged if the troops were not to be unduly delayed. It was known that the bridges were mined and that the Japanese occupied positions north of the river commanding the structures. At night an infantry battalion, preceded by a platoon of combat engineers and a mine detection detachment, moved to the south bank. The infantry forded the river to attack enemy forces in Bauang. Meanwhile, the engineers crept up to the bridges. One detail removed about zioo pounds of explosives

from the stringers of the south span; it had just finished the job when it was attacked by the enemy. One engineer of the platoon was killed in the skirmish in which the Japanese were repulsed. The bridges were captured undamaged. Late in March the 37th Division was sent from its garrison in Manila to relieve the 33rd Division in its coastal positions. Everywhere, progress was painfully slow.8

Filipinos help construct a road across a ford in the Santa Cruz river, Luzon

Southern Luzon

On 14 March XIV Corps, transferred from the east central front to southern Luzon, began the drive against the enemy in that part of the island. In the vanguard was the itth Airborne Division, which had been engaged in combat on southern Luzon since its landing at Nasugbu. Enemy resistance south of Manila was weak. The division’s 127th airborne engineers constructed and repaired supply and combat roads in hilly terrain, built and repaired bridges, operated ferries, and leveled off rice paddies for cub strips. They also took care of mines and booby traps and removed explosives from several bridges. Mount Macalod, on the southeast shores of Lake Taal, and Mount Malepunyo, ten miles east of the lake, were heavily mined. On the latter mountain, bombs and shells, hung in low trees, were not discovered until a patrol stumbled over the wires. Hampered by a lack of equipment usually furnished a combat unit, the 127th resorted to expedients and maximum use of local materials to perform its missions. In mid-March elements of the 592nd Boat and Shore Regiment supported part of the 158th RCT in a series of shore-to-shore operations

that lasted almost a week and that cleared the enemy from Calumpan Peninsula between Balayan and Batangas Bays in southwestern Luzon.

With the transfer of the i st Cavalry Division from central Luzon to the Bicol Peninsula on 23 March, the 8th Engineer Squadron also transferred its activities to that area. The men carried on their usual tasks. While constructing two ponton bridges, they encountered an unusual problem. Lily pads came floating downstream in such tremendous numbers that they threatened to wreck the bridges. The men stretched cables from bank to bank to catch the pads before they reached the bridges. By the end of March southern Luzon, except the Bicol Peninsula, had been cleared of the enemy.9

Corps and Army Engineer Units

Behind the front lines, engineer units assigned to corps and army were at work. Road maintenance, improvement of bridges, elimination of pockets of enemy resistance, and some base construction were the major jobs. Close behind the combat forces moving towards Bambang and Baguio were units of the 1136th Construction Group, working under I Corps. The corps engineers kept supplies flowing to the two fronts near Bambang and Baguio, operated sawmills, and built camps for the troops to use in the coming rainy season. Because the fighting was expected to drag on well into the wet months, the group’s principal job was to develop main supply routes for all-weather use. Highway 5, breaking down under heavy traffic, was resurfaced and repaired. In the Baguio area, where Highways 3 and it required extensive work, the engineers raised roadbeds above the level of the surrounding countryside, widened one-lane sections, and installed drainage facilities. In east central Luzon, the 1112th Construction Group worked on supply routes and bridges. At the end of March, when most of the group was transferred to Sixth Army for construction in rear areas, responsibility for engineer work in the XI Corps area was transferred to the combat engineers of the two divisions. On southern Luzon, the 1129th Engineer Combat Group under XIV Corps direction furnished support to the combat units. Among its tasks were the repair of the pier at Batangas, rehabilitation of the airstrip at Lipa, and operation of a sawmill and an ice plant.10

The Eighth Army Campaign—Palawan

Meanwhile, Eighth Army had begun its campaign in the central and southern Philippines. Palawan was the scene of the first landing. On 28 February a task force, made up mainly of the 186th RCT of the 41st Division, disembarked on the eastern shore of the island. Engineer units included two companies of the 532nd Boat and Shore Regiment, elements of the i 16th Combat Battalion, and the 1897th Aviation Battalion. The assault waves came ashore at the three designated

beaches, amid some confusion, in the course of which a number of the engineer craft missed their proper landing points; but all of this was not serious, since enemy opposition was nonexistent. The beachhead was quickly consolidated. No real resistance ever developed, and the last Japanese elements were wiped out in about a month. Little combat engineering was required. The 1897th engineers began to rehabilitate the airstrip at Puerto Princesa, badly damaged by bombing, and in 19 days had it ready for fighters.11

The Zamboanga Peninsula and the Sulu Islands

After bringing Palawan under control, troops of Eighth Army seized the Zamboanga Peninsula and the Sulu Islands. One hundred and fifty miles long, the peninsula was connected with the major part of Mindanao by a narrow isthmus, and, together with the Sulus, formed a series of steppingstones to Borneo on the southwest. On to March a naval task force began a bombardment of the coastal areas east and west of Zamboanga City, forcing the Japanese to abandon their beach defenses. Shortly after 0900, the infantry, assisted by elements of the 543rd Boat and Shore Regiment, landed west of Zamboanga City and was ashore in half an hour, encountering only light machine gun fire. Zamboanga City fell the first day. Subsequently, enemy resistance stiffened and a number of bitterly contested battles were fought. Nevertheless, the American forces continually expanded the area they held. Combat engineer operations, the mission of elements of the 116th engineers, were considerable on the peninsula, where well-camouflaged pillboxes, mine fields, barbed wire entanglements, and fortified caves and tunnels were numerous. The combat engineers destroyed about 50 caves and pillboxes and removed nearly 2,000 mines. They built about 50 miles of roads and rehabilitated or constructed 16 bridges, each capable of taking 35 tons.

The 370-odd islands of the Sulus, the southernmost ones in the Philippines, were mostly small, uninhabited, and unimportant. Three were of strategic significance—Basilan, Jolo, and Tawitawi. The campaign began with the landing of elements of the 41st Division on Basilan on 16 March. Other islands were seized later, including the main one, Jolo, where the only enemy resistance worth mentioning was encountered. In these operations, elements of the 543rd Boat and Shore Regiment helped land the infantry, and the 116th engineers carried out combat missions. Except on Jolo, little combat support was needed. On that island the engineers destroyed some enemy fortifications, removed mines, repaired and constructed bridges, and built about twenty miles of road. Construction units did additional work in the Sulus and on Mindanao. The 873rd Aviation Battalion rehabilitated airfields on the Zamboanga Peninsula and the Sulus, and other engineer units began to rehabilitate numerous local facilities.12

The Visayan Islands

To gain control of the remaining Visayan Islands, McArthur planned two operations, one by elements of the 40th DIvision, to seize Panay and western Negros, and the other by elements of the Americal Division, to recapture Cebu, Bohol, and eastern Negros. The 2nd Special Brigade, the 52nd and 57th Combat Battalions, the 865th Aviation Battalion, and the 239th Construction Battalion were to provide major engineer support. The first assault began on 18 March with the landing of elements of the 40th Division near Iloilo, capital of Panay. Eight days later, the Americal Division launched the second assault near Cebu City. These operations were similar to those against Palawan and the Zamboanga Peninsula. The naval and aerial bombardments drove the Japanese away from the beaches and forced them to retreat into the mountainous interiors, from which they could, as a rule, be routed only after long and arduous Campaigns.

The most effective enemy defenses were found on Cebu, where the landing forces came ashore just south of Cebu City. Starting across the beach, the troops discovered that the area was heavily mined and expertly camouflaged. Within a few minutes, eight vehicles were blown up. With men continuing to come in, beaches were soon jammed. A disaster would have been inevitable had there been any Japanese opposition besides light rifle fire. The engineers worked frantically to open a path through the mines. In back of the beaches and on the road to Cebu were numerous obstacles, among them antitank ditches, log walls, steel rails, and more mines. The obstacles were not much of a problem because they were not covered by fire. Cebu City, like the other major cities of the central Philippines, was practically deserted. Again, construction of roads and bridge building were by far the most important jobs. The 865th Aviation Battalion on Cebu and the 239th Construction Battalion on Panay and Negros rehabilitated shattered airfields and other facilities.13

Mindanao

The only large island in the southern Philippines the Japanese still controlled to some extent at the end of March was Mindanao. A successful campaign by American forces there would mean the end of Japanese power in the central and southern part of the archipelago. The Japanese on Mindanao were already in a precarious position because of the loss of the Zamboanga Peninsula and the in-Creasing harassment of Filipino guerrillas, led since 1942 by Colonel Fertig. In February 1945 Fertig had under his command some 33,000 men, half of them armed. Like the Visayan Islands, Mindanao offered many good opportunities for defense. Much of the island was mountainous, jungled, and swampy. Because of the relatively large size of the island, its few good roads, and its complete lack of railroads, overland operations would be extremely difficult.14

Assault planners tried to take advantage of the few favorable terrain features. An invasion of the east coast would be

impractical because of the high surf, the rugged shore line, and the almost impassable mountains farther inland. The north coast had many good beaches, in particular at Macajalar Bay, but high ground farther inland would give the defending forces a decided advantage. A major handicap on the southern coast would be inadequate communications with the remainder of the island. On the west coast were many good beaches and anchorages, and from this part of the island the interior was most accessible. Consequently, the initial assault was planned for that coast.

On 17 April two divisions of X Corps, the 24th and the 31st, landed near Parang. The 24th Division, with the help of guerrillas, advanced eastward along the highway leading to Davao. At the same time the 533rd Boat and Shore Regiment of the 3rd Special Brigade, together with naval units, moved some of the troops up the Mindanao River to secure the Fort Pikit—Kabacan area in the central part of the island, through which ran the Sayre (North-South) Highway. On 26 April elements of the 24th Division reached Davao Gulf, not far south of Davao, turned northward, and occupied their objective on 2 May. Meanwhile, the 31st Division had started up the Sayre Highway to split the Japanese forces in the northern part of the island. On 10 May, at Macajalar Bay, at the northern terminus of the highway, a second amphibious force came ashore and headed south. Everywhere Japanese troops were forced to retreat into the almost impenetrable jungles of the interior.15

“The engineer problem on ... Mindanao began with bridges and ended with roads,” said one engineer report. The story of the 3rd engineers of the 24th Division, almost from the time they landed until they reached Davao was one of “... bypassed bridges, rebuilt bridges and newly constructed bridges, of frantic efforts to get bridge timber and Bailey up forward. ...” The 106th engineers of the 31st Division likewise were occupied mainly with roads and bridges. Their first job was to improve the road net in the vicinity of the landing area. When the 31st Division started up the Sayre Highway from the Fort Pikit—Kabacan area, the 106th engineers, transferred to the highway a company at a time, furnished increasing support.16

In worse shape than the roads were the bridges. Between Kabacan and the first gorge, twelve miles to the north, demolished structures spanning shallow streams were either bypassed or hurriedly repaired to make rapid progress possible. The first real gorge, 120 feet across and 35 feet deep, with the bridge in ruins at the bottom, was a more serious obstacle. Stringing a cableway downstream from the site of the bridge, the engineers got jeeps, ¼-ton trailers, and howitzers across. Heavy vehicles would need a bridge. Because of the depth of the gorge, construction of a timber trestle was not practicable, and erection of a Bailey would be laborious, if not impossible. The men solved the problem in an ingenious way. They blasted out the sides of the gorge at the two approaches; the debris filled the gorge and made a crossing possible. The job was finished

in two days and two nights. The combat engineers had numerous chores in support of the infantry, arising from the fact that the Japanese had fortified strategic points with systems of caves and pillboxes and that enemy camouflage was excellent. Base construction was kept to a minimum, but as elsewhere, airfields and other facilities were rehabilitated.17

Borneo

As early as October 1944 the Allies had planned to seize certain areas of Borneo to deprive the enemy of vital oil supplies and to construct bases from which to cut Japanese communications with the Netherlands Indies. Plans called for three attacks, the first against Tarakan Island on 17 May, the second against Brunei Bay on 10 June, and the third against Balikpapan on 1 July. These assaults were assigned to Australian and Dutch troops, supported by American naval forces and elements of the 3rd Special Brigade. The 26th Australian Brigade and a company of the Royal Netherlands Indies Army took part in the operations against Tarakan. The first troops were put ashore on 30 April without opposition on Sandau Island off the east coast after withering naval and air bombardment had blasted the main landing area. Engineers and naval personnel went in and breached offshore obstacles in twelve places to permit LSTs to land. The Japanese did not try to defend their beach positions, and, after attempting to make a stand about 1,500 yards inland, were driven into the interior. Royal Australian Engineers had combat and construction duties.

At the Brunei Bay landing on to June, the task force included units of the 9th Australian Division. After the naval bombardment, landings were made unopposed. In view of the fact that the Brunei Bay landing would sever north-south communications, enemy reaction in this area was remarkably weak, being limited to only a few harassing air raids. The amphibian engineers were hampered somewhat in unloading operations on Labuan Island by the narrow roads and swampy conditions near the beaches. Elsewhere at Brunei Bay, landings were easily made. It was expected that the landing at Balikapan would be equally successful.18

The End of Organized Resistance on Luzon

Meanwhile, on Luzon the Japanese were being compressed into smaller and smaller areas. In mid-April the four divisions striving to reach Baguio and Bambang were still stalemated. Those on the Bambang front were tied down at Balete and Salacsac Passes, while in the Baguio area, the 33rd’s advance had progressed only a few miles up the strongly defended Kennon Road, and the 37th Division was having just as hard a time moving in from the coast. Engineer tasks in support of the infantry were as strenuous as before. The first breakthrough in the Baguio area came on 21 April when the 37th Division cracked resistance on Highway 9 at the Irisan River

Engineers use a Japanese Truck to support a temporary bridge in the Cagayan valley

gorge, and together with the 33rd DivIsion, took Baguio five days later. On 5 May the 37th Division was transferred to the Bambang area, where the Japanese were still holding up the 25th and 32nd Divisions. The job still requiring the greatest effort was the Villa Verde Trail, where the rains which began in late April compounded the difficulties. In May, the downpours increased in intensity, and work on the trail became impossible. The engineers reported, “... dozers dug themselves in as their tracks revolved without traction. ...” On 13 May the 25th Division finally captured Balete Pass. Reaching Santa Fe twelve days later, it turned west onto the trail and headed toward Salacsac Pass. Meantime, after a 3-month struggle, the 32nd Division broke through enemy strongpoints at the pass. On 29 May the two divisions met. Further engineer work on the trail had been halted three days previously, and all effort was henceforth spent on keeping open the part that had been improved.19

The stage was now set for the final drive down the Cagayan Valley. The plan was to have the 25th and 32nd Divisions

remain at Bambang and most of the 33rd Division at Baguio to clear out pockets of resistance. The 37th Division was directed to pass through the 25th Division and spearhead the drive north on the highway. It left Santa Fe on 31 May and made good time, averaging five or six miles a day. The 117th Engineer Combat Battalion had to move forward every two or three days to keep up with the infantry. Highway 5 was in fair condition, but most of the bridges were out. The company farthest forward operated treadway ferries until permanent crossings could be built, put in bypasses and culverts, and made minor road repairs. The next one along made major repairs to bridges, put gravel on bypasses, and occasionally built new bridges. The men put a floating bridge over the Magat River at Bagabag, some twenty miles north of Bambang. The 117th engineers also built several airstrips. At Bayambang, they blocked off a portion of a graveled roadway to serve as a runway; at Bagabag one hundred natives removed grass from an existing strip and filled small shell holes. The engineers were favored by the terrain in the flat, open valley, but the heavy rains were a major hindrance.20

To keep the enemy from escaping by way of Aparri, a small group of Filipinos and Americans—called the Connolly Task Force—had been organized to go rapidly up Highway 3 along the western and northern shores to Aparri. Engineer reconnaissance parties learned that much work would have to be done on the highway to permit the convoy of 200 vehicles to reach its goal. Two platoons of the 339th Construction Battalion went ahead of the main force, by road and by LCT, to repair bridges, remove landslides, and widen the road. The engineers also erected two hospital ward tents, built an all-weather airstrip, and installed and operated ferries.21

In east central Luzon, the advance was slow. Early in March the 43rd Infantry Division replaced the 1st Cavalry Division, which had been transferred to southern Luzon. On the 14th of the month XI Corps assumed command of the operation. An engineer company of the 6th Battalion had an unusual task on Mount Pacawagan, one of the numerous peaks on which fighting took place, and where the only possible route for a trail was along a hogback ridge. The men managed to get motorized compressors up the steep sides to drill holes in rock outcroppings, and then placed explosive charges in the holes to blow up the rock and make a roadway. They used i 00 smoke pots to screen their work from the enemy close by.

Early in May the final push began. The 38th Division with the 113th Combat Battalion headed for Montalban Dam, while the 43rd was deployed from the rear to take Ipo Dam. Road improvement continued to be the major job in support of the infantry. With the seizure of Ipo Dam on 17 May and the capture of Montalban on the 28th, both of them intact, the campaign in the Sierra Madres was virtually over. The engineers, even though they had not always been able to keep the infantry on the

move, had contributed much to final victory.22

Fighting continued in southeastern Luzon. On i April units of the 2nd Special Brigade landed the 158th RCT without opposition at Legaspi, near the tip of the peninsula. Squads of the 1279th Combat Battalion cleared the beach of mines which had not been detonated by the preinvasion air assault. The infantry started inland but was soon halted by the enemy near Daraga, a few miles northwest of Legaspi. While fighting raged, the combat engineers set about reconditioning the airstrip at Legaspi for evacuation of the wounded. Under enemy fire the first two days, the men cut grass, dug drainage ditches, and filled twenty large bomb craters with wreckage from the port. The strip was ready for operations on 6 April. Two days before, the engineers had started rehabilitation of the railroad. About 600 Filipinos, using hand tools supplied by the engineers, restored the shops and replaced tracks while the troops concentrated on bridge construction. On 10 April resistance at Daraga collapsed. The advance continued northwest on the Bicol Peninsula, where there were many well situated but poorly camouflaged mine fields and numerous roadblocks. On 12 April the 158th attacked the main Japanese force in the Cituinan Hills near Camalig; the same day the 1st Cavalry Division entered the Bicol Peninsula from the northwest. On 2 May elements of the 158th RCT and the 1st Cavalry Division met at San Augustin, and on 16 June, the Bicol Peninsula was declared secure.23

Before the end of June the Japanese on Luzon were almost completely crushed. On the 8th of that month, with organized enemy resistance in the east central part of the island at an end, the 6th Division, including the 6th Combat Battalion was transferred to the Cagayan Valley. The 6th Division started up the highway behind the 37th. At Bagabag the two divisions turned northwest on Highway 4 toward Kiangan, where remnants of the enemy were gathering. Fighting was approaching an end in northern Luzon. On 21 June Connolly Task Force, which had moved up the west coast, reached Aparri. Reinforced by one battalion of the 11th Airborne Division, it started south on Highway 5 two days later, and on 26 June its patrols met advance elements of the 37th Division at Alacan, twenty-five miles south of Aparri. The two units then started east to search for the enemy in the mountains. There were still some 65,000 Japanese left in northern Luzon, but they were largely unorganized and scattered. On 1 July Eighth Army relieved Sixth Army to carry on mop-up operations. Eighth Army also continued with mop-up operations in the southern Philippines. The operation against Balikpapan was carried out as scheduled on 1 July.24

Iwo Jima

Meantime, decisive combat and amphibious operations had been under way closer to the Japanese homeland. The islands of Iwo Jima and Okinawa, the former 800 miles south of Tokyo and the latter 900 miles southwest of the Japanese capital, had come under assault. Both were in the Pacific Ocean Area.

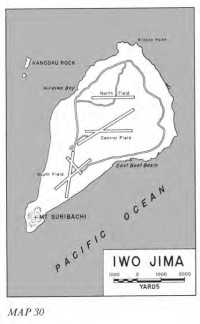

Admiral Nimitz had decided on the capture of Iwo Jima principally for two reasons: to make it impossible for the enemy to use the island as a takeoff point from which to bomb American bases in the Marianas, and to provide B-29 fields which could stage bombers headed for Japan and at the same time enable crippled planes returning from missions to make emergency landings. The capture of the island, and most base construction as well, was assigned to the marines and the Navy. Plans called for building three airfields: a large one with two runways for B-29’s in the center of the island, and two fighter fields with 5,000-foot runways north and south of the B-29 field. Most of the work was assigned to Seabee units. One engineer construction unit—the 811th Aviation Battalion—was scheduled to be sent in.25

The assault began on 19 February. After three weeks of bitter fighting, the island was secured on 16 March. The 811th engineers, the first Army unit to arrive, landed in mid-April and on the 27th of that month took over construction on North Field from the Seabees. (Map 30) The aviation engineers found that Iwo Jima (Japanese for Sulphur Island) was unusual insofar as terrain was concerned. Five miles long and two and one-half wide, it was of volcanic origin. Mount Suribachi, an extinct volcano 550 feet high, formed the southern tip. The northern half of the island was a flattened dome about 400 feet above sea level. Coral, usually found in this latitude, was absent. The surface of Iwo Jima consisted of volcanic ash, in various stages of consolidation, with the hardest resembling soft sandstone. Steam vents were numerous, and just a few feet under the surface, the ground was quite hot. When the 81 th engineers took over construction on North Field on 27 April, the runway was operational, but they still had much work to do on the field. Principal tasks included the building of taxiways, parking areas, warehouses, and roads.26

Okinawa

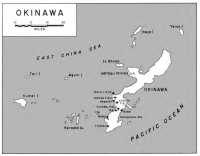

Stretching for approximately 600 miles from Kyushu to Formosa was a chain of islands known as the Ryukyus. Almost in the center was Okinawa, some 60 miles long and 3 to 10 miles wide, which the Joint Chiefs had for some time been considering as a site for an amphibious assault. The capture of this island by the United States would have grave consequences for the Japanese Empire. Control of Okinawa would enable American forces to develop airfields and bases from which to deliver crushing attacks on enemy communications and industrial

Map 30: Iwo Jima

centers. If the Japanese lost the island, their lines of communications with southeast Asia and the Netherlands Indies would be cut, whereas Allied communications with China would be secured. With Okinawa gone, the Japanese would not be able to carry on the war much longer.

Terrain

Favorably located from the strategic point of view, Okinawa was not the best site for an amphibious assault. It was a rough, generally mountainous, coral island. (Map 31) The northern two-thirds consisted almost entirely of rocky terrain, which aerial photographs indicated was covered by forests and heavy undergrowth. The southern one-third, not so mountainous, consisted in part of gently rolling country broken by ravines and limestone cliffs. About 80 percent of southern Okinawa was under cultivation, mostly in sugar cane and sweet potatoes. Along the coasts were rice paddies. The island’s shoreline was precipitous; mouths of streams broke the steep slopes in only a few places. Good landing beaches were scarce, the most likely ones being on the east coast at Nakagusuku Bay and on the west coast between Hagushi and Itoman. In back of these beaches were flat areas consisting principally of rice paddies—a potential hazard to vehicles. Most of the few roads and trails ran along the coast. Because of the rocky nature of the island, stone for road surfacing would in all probability be easy to obtain. Deposits of coral and of slate, conglomerate, and other types of rock were believed to be plentiful. There were small streams but no rivers. Since most of the waterways could be waded, they would scarcely be an obstacle from a military standpoint, and bridging, consequently, would be relatively easy. Rainfall was plentiful and occurred throughout the year, with the heaviest downpours taking place between May and September. From May to November, typhoons could be expected. The only city of any size was the capital, Naha, with a population of about 65,000. The slow reduction of enemy forces barricaded behind stone walls of an extensive urban area, which had been the case in Manila, was not anticipated.

Map 31: Okinawa

However, throughout the island, each house with its outbuildings was, as a rule, surrounded by a dense row of trees and often by a stone wall, ideally suited for defensive fighting. There were numerous burial vaults which would provide advantageous positions for the enemy.27

Engineer Planning

The capture of Okinawa had been assigned to Tenth Army. (See Map 31.) Consequently, Brig. Gen. George J. Nold, formerly engineer of the Alaskan Department and since June 1944 Engineer, Tenth Army, was responsible for overall planning for combat engineering. He and his staff had begun work in mid-October 1944. Since they expected combat support to be largely routine, they did not have to engage in extensive planning. The major concern of the

planners was obtaining enough engineer troops to provide adequate support for the initial amphibious assault and subsequent overland movement. Because only about 70 percent of the units requested were available, some adjustments had to be made.28

Planning for base construction on Okinawa was a complex matter. Since both the Army and the Navy wanted numerous facilities, the engineers in Hawaii had to make detailed calculations regarding location and size. The airfield program alone was tremendous. Six B-29 runways were to be built, together with a depot field, for the long-range heavy bombers. Also planned were 6 heavy bomber, 2 medium bomber, and 2 fighter runways, all to be constructed of coral. To support such an airbase storage tanks for about 1,800,000 barrels of gasoline, 6,000,000 square feet of warehousing, 12,500 hospital beds, housing for 375,000 men, 700 miles of road, and extensive harbor facilities at Naha would be needed. Estimates were that ninety engineer units would have to be sent to Okinawa to finish this construction on time. Higher headquarters also considered it advisable to put base facilities on small nearby islands. Those on Ie Shima, about two miles off the northwestern coast of Okinawa, would be the most extensive.29

For the assault on Okinawa, two corps were assigned—the Army’s XXIV Corps, including the 7th and 96th Divisions, and the Marine Corps III Amphibious Corps, consisting of the 1st and 6th Marine Divisions. In reserve were the 2nd Marine Division, afloat, and the Army’s 27th Division at Ulithi. The plan of campaign was a model of simplicity. Prior to the attack, Tenth Army’s 77th Infantry Division was to seize a number of small islands to the west—the Kerama Islands—where naval anchorages would be provided. Landing on the west side of Okinawa near Hagushi, both corps, the III Amphibious on the left and XXIV on the right, were to drive eastward clear across the island. Then the III Amphibious Corps was to turn north and destroy Japanese forces in the northern part of Okinawa; XXIV Corps would turn south, and drive the enemy forces toward the southern tip of the island until they surrendered or were destroyed. Since the Okinawa operation was to be carried out by Pacific Ocean Area forces, the island command or garrison type of organization for base construction was set up. Engineer units assigned to the garrison force for base construction were scheduled to land early.30

Planning for Amphibious Operations

The landings in this assault would differ from those in the Central Pacific Area in that an engineer special brigade organization was to be used. This was the Headquarters and Headquarters Company of the 1st Brigade, redeployed in late 1944 from France, and now under the command of Colonel Talley, formerly

in charge of construction in Alaska. The 1st Brigade differed considerably from the special brigades of the South-west Pacific. It was a shore organization only and had been converted from an amphibious-type unit while it was still in England preparing to engage in the 1942 North African campaign. Later, the only part of the brigade to be retained permanently was the Headquarters and Headquarters Company. For each operation, engineer combat battalions, and quartermaster, signal, ordnance, and medical units were attached. The organization of the 1st Brigade thus fitted in well with the Central Pacific’s shore party type of organization. The plan was to place the shore parties of XXIV Corps and III Amphibious Corps under the headquarters of the 1st Engineer Special Brigade.31

Operations to Mid-April

The Okinawa campaign began on 26 March. On that day, elements of the 77th Division landed on five of the islands of the Kerama group. The 302nd Combat Battalion supported the division; a company or a platoon was attached to each of the battalion landing teams. Missions were easily accomplished, including the provision of the usual support for the infantry and the destruction of enemy installations, equipment, and supplies.32

On the morning of April at 0830, XXIV Corps and III Amphibious Corps landed on the west coast of Okinawa near Hagushi. Weather and sea conditions were almost perfect. The only obstacle was a coral reef extending along the entire length of the 6-mile-long assault beach. Since the heavier landing craft could not cross over, men and cargo were transferred to LVTs and Dukws, but in some places even Dukws had difficulty crossing the barrier until the engineers prepared passageways with explosives and bulldozers. Japanese resistance was surprisingly light, the enemy laying down only occasional artillery and mortar fire, which caused few casualties and did little damage. As was so often the case elsewhere, infantry intrenchments, pill-boxes, and other defensive positions near the beaches were not occupied. About 2,000 posts had been placed along the southern part of the reef; apparently they were to have been strung with barbed wire, but no wire was found and the posts were easily removed. Once more, natural obstacles were more formidable than the enemy. Reefs, bluffs, and seawalls caused the troops to be jammed along the shore. Colonel Talley and his staff, initially using the shore party units of XXIV Corps and others assigned to the Island Command, were soon busily engaged in directing the unloading of supplies and moving them to dumps. Because the organization had too little time to work together as a team, there were some difficulties. Confusion in unloading was the result, in part, of the limited time available for planning and for integrating the organization. There was a noticeable shortage of Dukws and LVTs to haul supplies over the reef.33

Engineer Combat and Amphibian Support

As the troops moved inland, Japanese resistance continued to be light, and by noon of the first day, the troops had captured Yontan and Kadena airfields. By evening, some 50,000 men were ashore. The next day, again in the face of light resistance, the 7th Division reached the east coast. III Amphibious Corps now veered north, and XXIV Corps, south, and began their drives to the tips of the island.

During the next few days, the troops generally made rapid progress. On northern Okinawa, largely because the infantry advanced so swiftly, the major task of the Marine engineers was road repair. Before long, division and corps units were charged with the maintenance and repair of more than I oo miles of concrete highway. More bridging was required than the nature of the terrain had led the planners to expect. The engineers repaired damaged structures, mainly by putting in cribbing and timber supports, and replaced completely destroyed bridges with Baileys. Fords, dikes, and causeways were used whenever possible as temporary expedients. Mines and fortifications were almost entirely lacking. Water supply was sometimes difficult because of the rapid advance of the troops and the few satisfactory sources of water. Rehabilitation of Yontan airfield began on the second day.

On southern Okinawa, also, as XXIV Corps moved southward, division and corps engineer missions were light. Enemy resistance in any real sense did not materialize. The engineers had to give most attention to the roads in the interior of the island, where, narrow and only partly paved, they soon crumbled under heavy traffic. Division and corps engineers improved them with coral and rubble from the buildings of native villages. The 13th Combat Battalion of the 7th Division began rehabilitating Kadena airfield the day after the landing; the next day an aviation battalion took over; four days later the runway was operational. As the troops of XXIV Corps penetrated farther into the southern part of the island, they found increasing numbers of mines. Some were plastic; many were aerial bombs equipped with pressure detonators. Roadblocks, consisting of ditches, felled trees, and junked equipment, became common. The troops also came upon more booby traps. These various obstacles were no great hindrance to the advance of the troops in the first days of the assault.34

By mid-April operations on Okinawa were progressing well. All of the northern part of the island was in American hands, except isolated pockets of resistance on Motobu Peninsula. The troops were advancing toward the southern tip, though at a slower pace and against mounting enemy resistance.

Logistical support was proceeding satisfactorily. On the 9th, the 1st ESB had assumed control of all shore party operations in the XXIV Corps area and was scheduled to take over control of all unloading

on Okinawa, including that in the Marine beach areas, on the loth. The brigade in landing troops and unloading supplies had experienced occasional fire from the enemy. In general, amphibian operations on Okinawa indicated that an ESB headquarters company with temporarily attached units could not operate as efficiently as a complete brigade with permanently assigned boat and shore elements.35

Combat Support on Ie Shima

On 16 April two regimental combat teams of the 77th Division landed on Ie Shima. Daily aerial reconnaissance during the two weeks before the assault disclosed so few signs of enemy activity that it was widely assumed the island had been evacuated. When the first assault waves hit the beach, they found Ie Shima anything but abandoned. Enemy resistance was savage; even civilians armed with hand grenades and sticks took part in the fighting. The third regimental combat team, less one battalion, was sent in to reinforce the first assault troops. Elements of the 302nd Combat Battalion, attached to their respective combat teams, were busy reducing obstacles, removing mines, and destroying caves and pillboxes, and at times, fighting as infantry in hand-to-hand combat. The island was strewn with all types of mines—antipersonnel, antitank, and antiboat. The two airfields were heavily mined. The enemy made extensive use of aerial bombs, which were buried in the ground with fuses pointed upward. Improvised mines, consisting of 5-gallon cans of explosives fitted with a pressure-type fuse, were numerous. During the final stages of the campaign in the rugged eastern part of the island, the troops had to destroy hundreds of caves, some of them cut in the sides of cliffs and two or three stories high. The 302nd engineers during the fighting on Ie Shima removed about 2,600 land mines, and reduced 560 caves, pillboxes, and dugouts. For the 302nd this was the bloodiest fighting of the Pacific war. The battalion suffered men killed and 49 wounded. The island was finally secured on 21 April, but even after that mop-up operations were necessary.36

Southern Okinawa

Also on 21 April, three weeks after the initial landing, organized resistance on northern Okinawa came to an end. Fighting was over considerably ahead of expectations. But on southern Okinawa, a different story developed. South of a line running roughly from Kuba to Isa, in terrain admirably suited for defensive warfare and delaying tactics, the Japanese had constructed a defensive system so expertly devised as to be described as “fantastic.” Here the enemy, well entrenched in a rocky area honeycombed with caves and studded with pillboxes, blockhouses, and mine fields, put up a tenacious resistance. Not only was opposition on the ground formidable,

but also day and night air raids, including attacks by kamikaze dive bombers, and assaults by suicide boats and even swimmers harassed the American forces. In late April the 77th Division relieved the battle-weary 96th, and the 27th Division relieved the Marine 1st Division. On 8 May the latter returned to the lines and the Marine 6th Division was also sent in. There was now a two-corps front.37

Combat engineer tasks on southern Okinawa had been fairly easy up to now, but this was not to be the case henceforth. Only through hard fighting and with constant support of the combat engineers could the infantry make any headway at all. The enemy’s defense tactics were among the best encountered so far. One of the principal elements in the defense was cave warfare. On southern Okinawa the Japanese developed this type of fighting to the highest degree in the war. Many of their caves and other fortifications were on the sides of hills and cliffs away from the approaching American forces. The openings from which weapons were fired were so small as to be almost invisible. The enemy placed machine gun and mortar fire on the tops of the hills and ridges over which American troops had to advance to reach the mouths of the caves. Probably the greatest improvement made by the Japanese was to cover cave openings by fire. This was done in various ways. The most successful tactic was to make caves mutually supporting, with the entrance of each cave covered by fire from others located to the front and flanks. Sometimes machine guns, mortars, and even artillery would be emplaced in the open to cover cave entrances. The various weapons were, as a rule, so cleverly camouflaged that they were difficult to find. In the last desperate effort to prevent the destruction of caves by American forces, the Japanese would engage in grenade duels and hand-to-hand combat.

A number of weaknesses in cave warfare remained. For one thing, the small entrances greatly restricted the defenders’ field of fire. The lack of communications between caves limited the defenders’ ability to maneuver, counterattack, or withdraw. Japanese commanders cautioned their troops not to be trapped in caves. At the proper time at least one-third of the men were to leave and help cover the cave mouth from emplacements. But the defenders had little success in carrying out such orders. The Japanese were aware of the weakness of cave warfare, but had adopted it because of the overwhelming U.S. fire power and because of the chance cave warfare provided for slowing down the advance of the U.S. forces. The Japanese were making every effort to improve cave warfare and at the same time overcome its disadvantages.

The U.S. infantry-tank teams destroyed innumerable caves by using direct fire and flame throwers. The 8-inch howitzers of the artillery, and, at times, bombardment by aircraft proved very effective. The combat engineers were widely used to reduce caves and fortifications that could not be destroyed by direct infantry assault, artillery fire, or aerial bombardment, but had to be eliminated by hand-placed explosive charges. Engineer demolitions personnel

were organized in much the same way as in previous assaults in the Central Pacific. Usually a squad of from six to twelve men was responsible for front-line demolitions for an infantry unit as large as a battalion. If intelligence indicated numerous caves, pillboxes, and blockhouses in an area, an entire engineer platoon might be directed to support one infantry battalion. The battalion commander usually kept his engineer demolition teams near his command post in order to have them readily available should the infantry need help. While waiting to be called forward, the men prepared 24-pound satchel charges, which were the ones mainly used on Okinawa. Pole and shaped charges were, as a rule, too unwieldy or too heavy.

Called forward, an engineer squad operated in a more or less standard manner. The man in the lead advanced toward the cave with the charge and phosphorous grenades, followed by one or two others with spare satchels; the remainder of the group took up positions as directed by the squad leader. The infantry was in readiness to deliver protective fire. Reaching the mouth of the cave, the lead man threw in phosphorous grenades to blind the occupants. Next, the satchel charge was thrown in—as far as possible toward the rear of the cave—to get the maximum blast effect. Ten-to-fifteen-second delayed fuses gave the men a chance to get away from flying debris. The use of multiple fuses, some of which were dummies, made it difficult for the occupants, already at least partially blinded by the phosphorous grenades, to pull the proper fuse out of the charge before it exploded. Sometimes a second charge was thrown before the smoke of the first had cleared away. The aim was the complete destruction and sealing of the fortification. Moving in rapidly on the target and getting away fast were essential. Operating in this way, the engineers in the support of one front-line infantry battalion often used more than a ton of explosives to destroy about forty pillboxes, caves, bunkers, and ammunition dumps. Casualty rates were high. The Japanese brought intense fire to bear on demolition teams. During one 3-week period, for example, one engineer combat battalion suffered so percent casualties.38

The defenders of southern Okinawa made extensive use of mines. The American forces found no fields laid in a regular pattern, but standard and improvised mines were scattered about in great profusion. The only new type was the antipersonnel fragmentation mine. All mines, including those that were booby-trapped, were removed by 4-man engineer teams, one team being assigned to each tank platoon. Long demolition “snakes” attached to tanks were used in a few instances to clear paths through mine Fields. Armored bulldozers were extensively used to clear roads of obstacles. Booby traps were found in caves and sometimes in abandoned tanks.

Road maintenance in southern Okinawa was an arduous task for the engineers because the poorly surfaced thoroughfares broke down rapidly under the heavy traffic. From i 10 to 12 feet wide, most of the main highways were coral surfaced. During the prolonged

rains in May, maintenance became critical; in the XXIV Corps area, the engineers could keep but one main supply route open, and even this was possible only because corps and divisional engineers worked on the route continuously. After the rainy season, maintenance problems on roads were less serious, but bridging remained a major task. Bridges and culverts, almost invariably built of stone or reinforced concrete, and with a capacity of thirty-five tons or more, were adequate for much of the military traffic, but most bridges were only one lane. Baileys, used extensively on southern Okinawa, proved very satisfactory. There was little need for ponton bridges, and only three were put in place.39

The End of the Okinawa Campaign

Bitter fighting continued during May, and casualties were heavy as the defenders were pushed back slowly to the tip of the island. In June enemy resistance crumbled more rapidly. By the end of that month the Japanese position was hopeless. As the Americans pressed into the southernmost part of Okinawa, some of the defenders made last-ditch charges against American positions; many committed suicide. On 2 July the Okinawa campaign was declared officially ended.

Base and Airfield Construction for the Assault on Japan

While fighting was still in progress in the Philippines and on Okinawa, the

engineers in the rear areas were already building up bases and developing airfields from which U.S. forces were to launch the final assault on Japan. Two theaters, the Southwest Pacific and the Pacific Ocean Areas, were to be jointly responsible for the final assault. The major construction, by far, was being done in the Philippines and on Okinawa. In the meantime, finishing touches were being put on work in Hawaii and other islands of the central Pacific to support the attack on the Japanese home islands. Elsewhere, construction had slackened off greatly or stopped entirely. Some work was still in progress in the CBI theater, but in the South Pacific, the engineers were mainly dismantling bases.

Overall Organization in the Pacific

Despite changes in the tactical commands, no great modifications were made in the engineer organization in the Pacific in late 1944 and 1945. The greatest changes resulted from the Joint Chiefs’ activation of Army Forces, Pacific (AFPAC), on 6 April 1945, under the command of General MacArthur. Henceforth, all Army units in the Pacific, except those of the Strategic Air Forces, were under MacArthur’s direction. For the time being, the new command was only a nominal one since no immediate changes in organization were made. In the Southwest Pacific Area, GHQ SWPA continued to function as MacArthur’s headquarters for that theater, and MacArthur and Nimitz agreed that U.S. Army units in the Pacific Ocean Areas would remain under Nimitz’ control until he released them to MacArthur. Admiral Nimitz did not transfer the first

POA units to AFPAC until 31 August 1945, when MacArthur assumed command of all Army units in the Ryukyus, except those assigned to the Strategic Air Forces.

Engineer Organization—SWPA and AFPAC

When AFPAC was established, the forward echelon of Casey’s office was located in the Manila City Hall; the rear echelon was in the midst of moving from Leyte to the Philippine capital. Authorized strength of the office was 65 officers and 114 enlisted men. In April Casey’s request for an increase of 50 percent in personnel strength was granted. As Chief Engineer, SWPA and AFPAC, Casey had theoretical technical supervision over all U.S. Army and Allied engineer units in the Pacific. Probably his major task in his new position was to coordinate the activities of units insofar as possible in order to prevent duplication of effort. Coordination was especially necessary with regard to mapmaking organizations. In both the Pacific Ocean and Southwest Pacific Areas, they were already at work on or were about to be engaged in an extensive mapping program of the Japanese home islands.40

OCE USASOS

The office of General Ross, Chief Engineer, USASOS SWPA, had finished moving from Brisbane to Hollandia in November 1944. By this time, an ad vance echelon was already at Tacloban, Leyte; thereafter, additional elements moved forward, and by February 1945 the entire office was settled in Leyte. General Ross was now making preparations to move forward again, this time to Manila. An advance echelon, headed by Col. O. N. Rinehart, arrived in the Philippine capital in February. In April Col. Louis J. Rumaggi and the Operations Division, together with supplies and equipment, were flown there. They took over the third floor of one of the buildings of Far Eastern University and in a short time “were carrying on business as usual.” That same month OCE USASOS was officially set up in Manila.41

Engineer Districts

Since construction in the Philippines was to be so extensive and vitally important, proper organization would be highly essential. Especially in and around the metropolitan area of Manila, an immense amount of construction and reconstruction was necessary. As in Australia and New Guinea, General Frink, the commander of USASOS, organized bases to decentralize operations. He set up five, one on Leyte (Base K), three on Luzon (Base M at Lingayen Gulf, Base X at Manila, and Base R at Batangas), and one on Cebu (Base S). To supervise their operations, he had redesignated the Army Service Command, recently transferred from Sixth Army to USASOS, as Luzon Base Section, made it an intermediate headquarters, and placed it over

the bases. In April Luzon Base Section was renamed Philippine Base Section. In Australia and New Guinea, where engineer construction had been the responsibility of base section and base commanders, staff engineers exercised only technical supervision over engineer work. In the Philippines, engineer construction, initially the responsibility of the base commanders, was subsequently entirely divorced from their activities. It was assigned to engineer districts, which were similar to such organizations in the United States. To accomplish construction on Leyte, General Frink set up the Leyte Engineer District in February 1945 and made it directly responsible to General Ross. That same month, General Frink organized the Luzon Engineer District (LUZED) under Col. Alexander M. Neilson, placed it under Luzon Base Section, and made it responsible for USASOS construction on Luzon. Both districts differed from similar organizations in the United States in only one major respect—engineer troops and not contracting firms or civilian workers did the actual construction.42

The Engineer Construction Command

For some time considerable thought had been given to putting all engineer construction in the USASOS area under one command to be headed by an engineer. Generals Casey and Sverdrup and other members of MacArthur’s staff had discussed the desirability of making such a move in late 1944 and early 1945. Such an organization would be in line with the War Department’s policy of centralizing control of major technical activities in Headquarters, SOS, rather than delegating control of them to commanders of bases and advance sections, a policy the CBI theater had already implemented early in 1944.43 Sverdrup, made a major general on 5 January 1945, was especially interested in setting up such a command; it was generally assumed he would head it after Casey returned from the Army Service Command to his position as MacArthur’s chief engineer. On 20 February 1945, Sverdrup wrote Casey that it was “… rather obvious that a concentration of all construction forces within one organization is advantageous as centralized control properly exercised means far greater efficiency.” Sverdrup had in mind a construction command which would have under it various engineer districts. Two were already in existence and Sverdrup thought perhaps three more should be created. All would use troop units or contractors to get the work done. A fourth, organized along similar lines, would make use of Filipino workmen for rehabilitating Manila.44 A major question was whether to place such a command in GHQ, in USAFFE, or in USASOS. It was finally decided to put it directly under General Frink, since, as commanding general of USASOS, he was responsible for construction in the communications zone.

On 6 March the Engineer Construction

Command (ENCOM) was set up under Sverdrup, who was henceforth responsible for coordinating and supervising all construction in the Southwest Pacific that was under the control of USASOS. This meant, in effect, responsibility for construction in the Philippines, since the rear bases were by this time being dismantled. Engineer construction responsibilities in the communications zone in the islands were thus placed under one engineer command, which was completely separate from the base organizations. The men for Sverdrup’s new headquarters were taken on a temporary basis, mostly from the 5202nd Construction Brigade and from a number of aviation and construction battalions. The Leyte and Luzon Engineer Districts were transferred to ENCOM.45

The General Engineer District

A new engineer district for ENCOM was soon organized. Its establishment had, in fact, been under consideration since late 1944, when it seemed likely that an extraordinary effort would have to be made to rehabilitate and reconstruct facilities in and around Manila after the Japanese there had been defeated. Colonel Lane, chief of Sverdrup’s Operations Division, was one of the first to suggest using a district organization to rehabilitate the Philippine capital. He wrote Sverdrup on 26 November 1944: “In connection with plans for rehabilitation of Manila, it has occurred to me that it may be desirable to establish an Engineer District Office ... and that the Chief of Engineers could probably furnish a complete District with all personnel for this work. ...” Lane stated that such an organization should plan to use as many Filipino civilians as possible in order to free the troops for more direct combat support. Since local contracting firms would in all likelihood not be available, large numbers of hired laborers would have to be used.46 On 5 December MacArthur radioed a request to the Chief of Engineers for an organization similar to an engineer district office in the United States. “The limited number of engineers at my disposal,” MacArthur pointed out, “will be fully occupied in direct support of the campaign. ... This means that the maximum use must be made of civilian labor.”47

In line with MacArthur’s request, Reybold began recruiting men for the new office. Some 150 officers and 300 enlisted men were supplied by division and district offices in the United States. They received a few weeks training at Fort Belvoir and then flew to Manila, arriving in late March. Headed by Col. Robert C. Hunter they were designated the General Engineer District (GENED). It was hoped that at least some of the reconstruction projects could be given to local contractors, but this idea was quickly given up. There were few Philippine construction firms before the war and these were now unable to do any effective work because of the dislocations

caused by the conflict. Colonel Hunter had to rely at first on hired labor. He had the usual difficulties of organizing and supervising such a large work force. Fortunately, many of those hired had been employed by the U.S. Army before the war and so had gained experience for the work they had to do. Because of the vast amount of destruction, however, Hunter, contrary to original plans, soon had to use large numbers of troops.48

Construction Corps of the Philippines

Although Sverdrup had considered organizing a number of additional subordinate commands, only one more was formed—the Construction Corps of the Philippines (CONCOR), organized to make further use of Filipino workmen. It was set up on 25 April, under Col. Samuel N. Karrick, to undertake reconstruction in the Philippines, especially in and near Manila. Workmen, recruited on a voluntary basis for a minimum period of six months, would be directed by American and Filipino officers. This type of organization was expected to make possible a more efficient use of the Filipinos by providing better organization and supervision and reducing labor turnover. The workmen were to be organized into labor battalions. At full strength, each would have 92 officers and enlisted men from the U.S. Army, the Philippine Army, and the Philippine Scouts, and 1,037 civilians. A CONCOR battalion had a special table of organization and equipment closely resembling that of the former Civilian Conservation Corps battalions in the United States. Recruitment was slow, and by I June, CONCOR had only one battalion. Thereafter, expansion was more rapid, four battalions being activated in June. Including both skilled and unskilled workers, the battalions became quite efficient in all types of construction, except possibly those requiring much earth moving. They built barracks, warehouses, and hospitals, and maintained roads and utilities. Labor turnover was of serious concern at first but became less so as the organization was improved. Though wages were low, many Filipinos were attracted to the organization mainly because it provided meals at cost and permitted employees to buy scarce articles in the Army’s post exchanges.49

Changes in ENCOM

In the rapidly changing conditions in the Philippines, Sverdrup’s staff, and his subordinate commands as well, underwent almost continuous modification. During the first months the number of men in ENCOM headquarters fluctuated greatly. In June the War Department authorized a staff of 114 officers and 652 enlisted men. Meanwhile, Sverdrup found himself directing the construction efforts of a larger and larger engineer force. Late in April, he had acquired an additional unit. This was the Boat

Building Command, which had been established in mid-1944 at Milne Bay to direct the activities of the boat assembly units in the theater. In early 1945 the command was transferred to Batangas, Luzon, where the men rebuilt their assembly plants and were soon putting landing craft together again. The Luzon Engineer District also expanded rapidly, and by the end of April, Colonel Neilson had about 250 military and civilians on his staff. Within the next few weeks, he had some 30,000 engineer troops and over 20,000 Filipino civilians working on various projects. The General Engineer District likewise grew rapidly. When the Leyte Engineer District was inactivated in May, GENED took over its projects, and it took over LUZED’s when that organization was inactivated in July. By then, the General Engineer District had under its control most of the military construction in the USASOS area in the Philippines.50

The type of construction organization that many engineers had wanted since the early days in Australia, one headed by an engineer officer, was now a reality. Nevertheless, many of the difficulties previously experienced were still prevalent, undoubtedly because they were too basic to be easily eliminated by a change in organization. Shortages of men and supplies were still the rule, as were the problems generally encountered in coordinating a construction effort over a vast area in a short time. Some felt that ENCOM, directing work formerly handled well enough by base section and base commanders, was merely another headquarters that had to be dealt with. From the standpoint of many engineers, ENCOM had the great advantage that it was an engineer command. Engineer units of such a command were more likely to receive a sympathetic understanding of their problems than they could get from nonengineer base and base section commanders. ENCOM consequently improved the morale and efficiency of engineer units. It further raised morale by giving a number of promotions that could not be granted earlier because of limitations in the tables of organization.51

Army Forces, Western Pacific

On 7 June USASOS was redesignated Army Forces, Western Pacific (AFWESPAC) and placed under the command of Lt. Gen. Wilhelm D. Styer. Somewhat expanded in functions over its predecessor, AFWESPAC was to provide logistic support for U.S. Army troops in SWPA and AFPAC as directed by higher headquarters. On 10 June, General Worsham, formerly division engineer of the Northwest Service Command in Canada and Alaska, became Engineer, AFWESPAC. His staff was one of considerable size, by the end of June consisting of 144 officers, 435 enlisted men, and 33 civilians—a total of 612. AFWESPAC had more than zoo engineer units numbering about 65,000 men, and within a month the figure had risen to 90,000. Engineers made up

one-fourth of all the troops under AFWESPAC’s command. Worsham’s staff was before long concerned primarily with the construction and maintenance of bases needed to support the invasion of Japan and with making plans and preparations to furnish the engineer troops and supplies required for that assault.52

Construction in the Philippines