Chapter 1: Administrative Organization

Traditionally, the OQMG had been organized along commodity lines, and the outbreak of war in Europe in September 1939 brought no significant departure from this basic principle of commodity administration. The OQMG was then operating under a simple plan of organization which, except for minor variations, had been in effect since 1920. Of the four divisions handling Quartermaster activities, the Administrative Division combined within its province functions which were of a staff character. The Supply Division, consisting of a number of commodity branches, handled the procurement and distribution of Quartermaster supplies. The functions of construction and transportation were vested in two self-contained divisions.

The extended period of the emergency, which lasted from the presidential proclamation of limited emergency in September 1939 until 7 December 1941, provided an opportunity for orderly administrative development and expansion. However, the great expansion of Quartermaster activity did not begin until mid-1940, after the fall of France had increased the apprehensions of the United States and defense preparations were accelerated. On the eve of that expansion the QMC acquired a new Quartermaster General, who was to guide its activities throughout World War II. Maj. Gen. (later Lt. Gen.) Edmund B. Gregory was first appointed for a four-year period beginning 1 April 1940, and upon the expiration of this term he was reappointed acting The Quartermaster General, relinquishing the office on 31 January 1946. Having spent the greater part of his thirty-six years in the Army in the service of the Corps, he brought a well-rounded knowledge to bear upon Quartermaster problems.1

Expansion of the Organization

In order to handle its increasing activities, the OQMG for the most part multiplied its administrative units by expanding sections into branches and by separating branches and establishing them as independent divisions. Nearly all this subdivision occurred within the Administrative Division. The one exception was the creation of the important Motor Transport Division in the summer of 1940 by separating it from the Transportation Division.2 Fiscal and personnel activities were separated from the Administrative Division and given divisional status.3 Within a few weeks, the expansion of numerous activities of the Administrative Division was recognized by the addition of a Statistical and Public Relations Branch and a Storage Control Branch to the already existing Production Control, and War Plans and Training Branches. All four handled important planning and staff activities.4 By the close of the year the Memorial Branch was raised to a division.5

More significant than this increase in administrative units was the important realignment of

staff and operating phases of Quartermaster organization which occurred during this period. For example, the activities of the War Plans and Training Branch were separated. Its military training functions were transferred to the Personnel Division. Its planning functions, along with the activities of the Contracts and Claims Branch of the Supply Division, were vested in a new War Procurement and Requirements Branch in the Administrative Division.6 This furthered the concentration of planning and policy functions on the staff level. Unfortunately this development made the Administrative Division unwieldy; the need for reorganizing certain of its important activities became apparent.

The most important basic reorganization in the OQMG before Pearl Harbor was initiated in a series of orders early in 1941. These were formalized and integrated later in the year by a revision of the basic organizational directive of the OQMG.7 Separation of the Administrative Division’s functions of administrative service from those of policy control constituted the most obvious need. Some of the former functions, namely those pertaining to departmental or headquarters activities, had a tendency to gravitate toward the executive office; hence a separate supervisory Executive Office was established as a formal agency under The Quartermaster General. To this office were transferred the activities of communications and central records, the OQMG library, a welfare service, and other miscellaneous office services. Attached directly to the Executive Office was an Executive Officer for Civilian Conservation Corps Affairs, charged with the control and supervision of all duties of the Corps pertaining to its participation in CCC matters. An Executive Officer for Civilian Personnel Affairs was responsible, under the direction and supervision of The Quartermaster General, for formulating and administering all policy matters relating to civilian employees of the Corps.8

The remaining administrative service functions were retained in the Administrative Division, which was renamed the General Service Division. It supervised those services of an administrative nature which pertained primarily to field activities and handled all administrative matters of general concern not assigned elsewhere.9 In the basic chart10 drawn to prescribe OQMG organization at this time, this division and the Executive Office as well as the Fiscal, Civilian Personnel, Military Personnel and Training, and Planning and Control Divisions were placed in theoretically close association in a group of “Executive Divisions.”

The establishment of the Planning and Control Division early in 1941 resulted from the need to coordinate basic operating functions scattered throughout the commodity branches. As problems relating to procurement and other functional aspects of supply activity increased with the developing emergency, the necessity for a control agency became increasingly more compelling. After administrative and policy phases of control had been separated, the necessity to consolidate, reorganize, and refine the latter phase under a single agency became basic in the reorganization of OQMG activities. In establishing the Planning and Control Division, the procurement control, storage control, and war planning and requirements functions of the former Administrative Division were transferred to it as well as that division’s activities in reference to statistics, claims, and contracts. In addition, the war planning activities of the Personnel Division were transferred to it.

Staff operating relations between the Planning and Control Division and the Supply Division during the emergency period developed

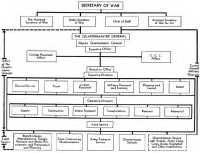

Chart 1: The Quartermaster Corps in the War Department: 1941

considerable friction. There were present, of course, the normal irritations and difficulties incident to expansion of personnel and perfection of organization. Furthermore, the personalities and policies of certain of the key staff and operating officials inevitably played a part, while the reluctance of the operating units to accept direction and “interference” was undoubtedly a contributing factor.

As to the general resistance of the operating divisions to control, it is significant that a formal attempt was made to minimize this factor through designation of the staff units as “Executive Divisions.” The chief of the Planning and Control Division was intended to have general powers of direction over the activities of the OQMG, but these were translated with difficulty into binding orders on procurement, distribution, and other activities. The operating divisions were encouraged in their independence by the relative unfamiliarity of the staff agencies with operating problems and their uncertainty as to the scope of their jurisdiction and power. In any event, commodity branches and divisions had long been accustomed to having complete and integrated responsibility for their operations.

Conflict and confusion in policies were even more basic causes of the difficulties. These developed out of the uncertainties which stemmed from the fact that the country was drifting along through a period of partial or limited mobilization, whereas the procurement planners had based their plans-on abrupt and complete industrial mobilization for war.

For twenty years following the passage of the National Defense Act, the procurement planners in the OQMG under the guidance of the Assistant Secretary of War had been formulating war procurement plans to meet a future emergency. Such planning had been separated from current peacetime operations in the commodity branches of the Supply Division, and it had followed a radically different line from that of the operators in the commodity branches who were developing a centralized procurement system. Regional self-sufficiency and decentralization of procurement to districts that were roughly coterminous with the corps areas constituted the heart of the procurement plans that were drafted. Policies stemming from such a decentralized system were obviously at sharp variance with those of centralized operations which carried over into the emergency period. The planners were further handicapped in carrying out their policies since procurement plans were intended to be put into effect on an M Day (Mobilization Day) which never came. Instead a wholly unanticipated, prolonged emergency period occurred, with the result that the plans were held in abeyance and operating personnel met the day-to-day problems by using established peacetime procedures. By the time war was declared, the momentum was too great to permit a resort to the plans that had been prepared.

Because the emergency period was primarily one of procurement effort, administrative adjustments naturally revolved around this activity, and staff-operating relationships must be considered first in reference to it. The production control agencies were somewhat intolerant of concessions which had to be made as a result of the actual course of emergency transition. They were opposed to alternative systems and methods which negated the economic and industrial benefits long planned through controlled mobilization and production. On the other hand, the approach of the current procurement agencies to this matter was more expedient. They recognized the difficulty under the circumstances of securing an ideal distribution of orders and allocation and full utilization of industrial facilities. They were interested primarily in pushing those policies which seemed acceptable and practicable in meeting procurement objectives.11

Both production and purchasing policies

relating to selection of contractors and facilities were affected by various complex factors—profit and competitive motives, business pressures, indecision on the part of higher planning agencies in the government, and other elements which tended to interfere with the procedures of mobilization developed by the procurement planners. The latter had formulated programs for allocating contracts to industrial facilities, but depot personnel ignored their advice in carrying out current operations. Most depot officers and many officers in the Supply Division were also extremely timorous about abandoning peacetime purchasing policies and adopting the method of negotiation advocated by the planners. The Supply Division, for the most part, pursued a legalistic and hesitant approach to emergency purchasing and production. Commodity organizations on all levels resisted or resented the pressure exerted by the staff units for the application of new and more radical policies and methods.

Such differences probably acted as the greatest single deterrent to extension and perfection of administrative controls on the part of the staff agencies of the Planning and Control Division. But while the heritage of a ready-made set of controls would have been of inestimable value after Pearl Harbor, it must be emphasized that relatively loose supervision could be tolerated before that time. Insofar as the supervision of procurement policies by the Planning and Control Division was concerned, the situation could even be rationalized as consisting merely of a necessary, if troublesome, stage in the process of transition to war.

Considerations of administrative control and orientation were highly interdependent in all phases of procurement. One more illustration emphasizes this point. There was considerable pressure for expediting procurement, but production scheduling could still be viewed primarily as a fiscal matter and accomplished in the course of distributing appropriations and funds. The need had not yet developed for tight scheduling and therefore for welding the computation of requirements, based on distribution and other field data, and the issuance of procurement directives into a single, coordinated process. OQMG staff-operating conflicts over this phase of procurement control, however, were already present.

If administrative adjustments thus far had centered particularly on procurement activities, developments were looming nonetheless in other fields, especially with respect to the distribution of supplies. The former Storage Control Branch of the Administrative Division had remained for a time with the Planning and Control Division, but by May 1941 it was transferred to the Executive Office as a staff unit and renamed the Depot Division.12 This division functioned as the agency dealing with Quartermaster depots and Quartermaster sections of general depots on all general matters of depot administration in which the various OQMG divisions had an interest. It also served as the supply agency for warehouse equipment of all kinds, kept records bearing on the allocation and utilization of storage space, and initiated the procurement and training of personnel to meet the requirements of new depots. In the summer of 1941 Quartermaster depots and Quartermaster sections of general depots tended to operate as separate autonomies rather than as parts of the depot system. Each installation was using various methods and systems for doing business with little regard for the existence of similar supply organizations. It was the mission of the Depot Division to standardize and coordinate the activities of these installations and to insure the efficient operation of the individual depot.13

A weakness in the position of the Depot Division lay partly in the looseness of its responsibility for the administrative servicing and planning on the field level of a variety of activities for which other divisions often claimed primary responsibility. It was enjoined specifically from interfering with the “prerogatives of Chiefs of Operating Divisions” in supervising the procurement, storage, and issue of supplies. At the same time it was made the main channel of contact with the depots on those matters of administration in which it dealt, a function normally assigned to an operating agency at headquarters. Because it was difficult to distinguish activities of general concern from those which were prerogatives of the operating units, there was ample ground for friction to develop with the commodity branches of the Supply Division.

As in the case of procurement, so in distribution there was no need during these months for rigid control. Just as the tight scheduling of requirements depended upon influences developing later in the war, so inventory and stock control were hardly required at this time, and the Depot Division concerned itself, insofar as its administrative functions were involved, only with standard organization and procedures in depots. The placing of stock accounting and reporting activities on a machine basis in 1941, however, superseding the old manual system, presaged the emergence of control problems as well as the need for functional realignment of distribution activities.14

Although a number of other changes, including the setting up of a lend-lease agency in the OQMG, occurred in the last few months before Pearl Harbor, the administrative adjustments involved in the staff-operating relationships on procurement and distribution constituted the main lines of development. In the pre-Pearl Harbor period, despite the development of functional controls and services and a general tendency to concentrate them in staff units, the OQMG remained organized fundamentally on the commodity principle. Subject to directions from higher authority and to varying degrees of functional supervision and aid from agencies within the OQMG, each commodity branch retained fairly complete responsibility for the handling of a group of supply items, from determining requirements to seeing that such items reached points of issue.

Transfer of Functions

War was to bring further changes in the administrative organization of the OQMG and in the mission assigned to the Corps. Within a few months after Pearl Harbor, a number of important functions were lost to the QMC. As in World War I, construction, transportation, and motor transport activities were again either transferred to other technical services or established as separate organizations.

Construction

In the case of construction, action to remove this function from the QMC was actually begun in the fall of 1941 and completed a few days before Pearl Harbor. In September the War Department submitted a bill to the House of Representatives, providing for the transfer of new construction for the Army and the maintenance and repair of buildings from The Quartermaster General to the Chief of Engineers. To justify this transfer the Secretary of War urged that it would eliminate a large amount of duplication of effort, cost, and administrative personnel. A more efficient long-range program of construction could be set up. The proposed bill placed the construction work of the War Department under the Corps of Engineers because, even in peacetime, with its river and harbor and flood-control projects, the Corps of Engineers, unlike the QMC, had a

large construction program. It was argued that it also had a long-established organization to handle such work, whereas the organization of the QMC for these activities was of much more recent creation. Finally, it was urged that the construction activities of the War Department during the emergency were more closely related to the other functions of the Corps of Engineers and to the training of combat engineer forces than they were to the other functions of the QMC.15

The Quartermaster General, General Gregory, took exception to the reasons advanced for this transfer. He observed that if housing for the Civilian Conservation Corps were included the Quartermaster expenditures for construction for the past ten years would be larger than those of the Engineer Corps. This program had been carried out in an economical and satisfactory manner. Moreover, a small, continuous, permanent housing construction program had been handled by the Construction Division, OQMG. In any case, neither the peacetime construction program of the Corps of Engineers nor that of the QMC was comparable to the load of construction in an emergency. In addition, the type of work done by the Engineer Corps was quite different from that involved in the construction of troop housing. Except for a period during World War I when a separate Construction Division was formed, the QMC had handled construction at military posts for more than one hundred years. In The Quartermaster General’s opinion the training of combat engineering forces had very little in common with the construction work involved in the zone of interior. He objected to the transfer of maintenance activities and the repair of buildings and utilities, for these were intimately involved with the functions of the Corps at all military posts.

In short, the Quartermaster Corps is already on the job. It is in intimate touch with every phase of Army life. There is a Quartermaster Officer wherever a group of soldiers can be found. The Engineer Corps, on the other hand, handles specialized work usually completely aloof from the rest of the Army and entirely out of touch with the day to day life of military organizations.16

Although The Quartermaster General objected to losing the construction function, the War Department and the Construction Division, OQMG, had been much criticized by the Truman Committee for the excessive cost of the construction program for camps and cantonments. The committee had recommended that the Secretary of War be granted authority to assign additional construction work to the Corps of Engineers. Air Corps construction had already been assigned to the Engineers by Congress in 1940.17

Under these circumstances there was little doubt that the bill offered by the Secretary of War would be enacted into law. The Quartermaster General was therefore directed to collaborate with the Chief of Engineers in developing a plan for the transfer of construction activities. Such a plan was submitted in November.18 On 1 December 1941 Congress passed the law transferring construction, real estate, and repairs and utilities activities to the Corps of Engineers, a transfer that was made effective on 16 December 1941.19

The QMC had borne the major burden of construction during the emergency period. Although it had been very critical of this program, the Truman Committee observed:

By making such criticism the committee does not wish to detract in any way from the very important fact that housing, training, and recreational facilities for 1,216,459 men were provided in the space of a few short months and in most instances were finished and ready for occupancy before the troops arrived. The Construction Division of the Quartermaster General’s Office supervised the construction of projects which . . . due to their size and the necessity of speed, presented some of the greatest problems ever encountered by any construction agency in this country and the facilities so provided are better than the troop facilities possessed by any other country. Adequate provision has been made for the comfort and health of the soldiers. Furthermore, the facilities are better than those provided for the troops in the last World War.20

Transportation

Three months after the transfer of construction, as part of the general reorganization of the Army in March 1942, responsibility for transportation and traffic control was centralized in the Services of Supply (SOS), and the Transportation Division, OQMG, was separated from that office.21 In the years since 1920, when Congress by legislative action had returned transportation activities to the QMC despite recommendations for the establishment of a permanent transportation corps, decentralized operating responsibilities had developed. The Quartermaster General was responsible for the movement of troops and supplies by common carriers in the zone of interior and by Army transports and commercial vessels between the United States and its overseas bases. Commanders of ports of embarkation, however, reported directly to the War Department General Staff. Their functions in regard to Army transports were not clearly differentiated from those of The Quartermaster General. The chiefs of other supply services maintained separate traffic organizations to look after their transportation interests such as shipping and procuring agencies. The Supply Division, G-4, of the General Staff exercised over-all supervision of transportation activities.22

This decentralization was the real weakness of the transportation organization. In the period of the emergency, when overseas bases were being strengthened and transportation difficulties were multiplying, the Transportation Branch of G-4 promoted the coordination of Army transportation activities. Its activities expanded even more rapidly after Pearl Harbor. But this coordination offered no real solution to the problem, which stemmed from the fact that no one operating organization was directly responsible for inland, terminal, and overseas transportation.23 This was provided in March 1942 by consolidating all War Department transportation and traffic control under SOS. A Transportation Division, in charge of a Chief of Transportation, was established in the SOS. By 31 July 1942 it emerged as the Transportation Corps.24

Motor Transport

The last important change made in Quartermaster activities during the war was the transfer of motor transport activities in the summer of 1942. Long before this there had been rumors of impending changes. The Under Secretary of War was concerned with the problem of utilizing industrial capacity to the best advantage. He directed John D. Hertz, an authority on motor transportation, to make a special study of the subject, primarily from the viewpoint of effective use and conservation of automotive equipment already on hand. The scope of this survey was restricted to vehicles of Quartermaster responsibility, and consequently tanks and other combat vehicles, which were procured by the Ordnance Department, were excluded from consideration in this investigation. The report of the Hertz committee, submitted in November 1941, recommended that one service be made completely responsible for all automotive maintenance. This control agency was to be established in General Headquarters inasmuch as the committee had found the activation of a Headquarters Motor Transport approved in a Table of Organization, 1 November 1940. The Hertz report recommended no change in jurisdiction over procurement of motor equipment.25

A month earlier the General Staff had considered the reorganization of the armored division, one aspect of which had involved the delegation of all third echelon vehicle maintenance to the divisional ordnance battalion.26 At that time both Ordnance and Quartermaster personnel maintained such third echelon activities. While acknowledging that this led to duplication of overhead, equipment, and effort and that this responsibility should rest with one agency, The Quartermaster General had urged that it be placed with the QMC because about two thirds of the 3,300 motor-propelled vehicles provided for an armored division were procured by the Corps. All but about four hundred of the vehicles used commercial-type motors.27 In January 1942 Brig. Gen. Brehon B. Somervell, then Assistant Chief of Staff, G-4, informed The Quartermaster General that orders were being issued to the Army directing the pooling of third and fourth echelon shops of the QMC and the Ordnance Department.28

Many officers of the Motor Transport Division, OQMG, hoped that a separate corps would be established. General Somervell also favored a separate automotive corps, which would be responsible not only for maintenance but also for design and procurement of tanks and other combat, as well as noncombat, cars.29 In an analysis of the Hertz report submitted to the Chief of Staff, he emphasized that “the reconditioning of the present automotive fleet, the proper instruction of the present personnel, the provision of the necessary training of maintenance units for the increased automotive fleet laid down in the program provide a tremendous problem which must be solved within the year 1942 if our field armies are to wage successful

mechanized or motorized warfare.”30 In his opinion, however, the existing division of motor transport responsibilities among the QMC, the Ordnance Department, the Corps of Engineers, the corps areas, the General Staff, General Headquarters, and the field armies would prevent the accomplishment of this program.

Insofar as maintenance was concerned the Hertz report had found existing procedures clearly defined and adequate for a satisfactory maintenance program. This led the Assistant Chief of Staff, G-4, to conclude that the fault rested in the controls established and the lack of attention given to this vital problem by the high command. Maintenance companies had been authorized months after equipment had been put in service, spare parts had not been ordered with vehicles, and efforts of The Quartermaster General to create an organization at General Headquarters to supervise maintenance had been disapproved on the recommendation of that agency. The latter’s failure to provide adequate training had stemmed from the view of the Chief of Staff-, General Headquarters, that “maintenance of modern commercial vehicles is not a serious problem, provided sufficient spare parts are available promptly.”31

The Chief of the Armored Force and the Chief of Field Artillery were strongly in favor of the organization of a separate automotive corps as proposed by the Assistant Chief of Staff, G-4. The advocates of such a separate service urged that it would heighten combat efficiency, give access to the high command, promote economy of material and personnel, and provide a vitalized service with no other interests. In opposition was the weight of tradition, of “vested rights and privileges.”32 The opponents of a separate service objected to reorganization in the midst of war, claiming that confusion would result even if advantages did accrue at a later date. In the opinion of the Under Secretary of War the transfer of responsibility for the design and procurement of tanks and other combat cars from the Ordnance Department to an automotive corps would be unfortunate. The Deputy Chief of Staff concurred. He felt that the resulting confusion would cause delay in procurement and development of tanks, self-propelled antitank guns and artillery, and other automotive equipment of the Ordnance Department.33 The Chief of Ordnance and The Quartermaster General strongly opposed the establishment of a separate automotive corps. The idea was discarded for the time being. Instead, both the QMC and the Ordnance Department made efforts to improve their field services, and the OQMG strengthened its Motor Transport Division.34

In May 1942 General Somervell, as Commanding General, SOS, visited the European Theater of Operations (ETO). While there he became interested in the unified maintenance organization of the British Army. Upon his return he was more than ever convinced of the desirability of combining maintenance for Ordnance and Quartermaster automotive and tank equipment under a single head.

Developments which culminated in the transfer of motor transport functions from the QMC to the Ordnance Department now moved rapidly. On 22 June 1942 General Somervell sent a memorandum to Lt. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, discussing some of the difficulties encountered in World War I because the organization of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) differed from that of the War

Department. In this connection he asked whether a separate motor transport corps, entirely divorced from the QMC, were desirable. Within a week an affirmative message was received from General Eisenhower’s headquarters. On 3 July SOS informed The Quartermaster General that the establishment of a separate automotive corps was under consideration and invited him to submit his views on the matter.35

General Gregory vigorously opposed the move. He outlined the current duties of the Motor Transport Service to show that it was not a transportation service but a supply organization which purchased, stored, and distributed general-purpose vehicles, parts, and equipment. The Army commands were responsible for the operation of the vehicles assigned to them. He urged that the distinction between the activities of the Motor Transport Service and a transportation service should not be lost. He asserted that the establishment of a separate motor transport corps would create many new problems.

While he conceded that there might be certain advantages in creating an automotive corps to carry out the functions now performed by the QMC, General Gregory declared that it was his belief that “the activities involving design, procurement, storage and distribution, and the operation of base shops are now being administered and controlled effectively.” The procedures under which these activities were operating were understood by all, and constantly increasing effectiveness could be expected as field commanders came to realize more keenly the importance of “strict command supervision over the operation and maintenance of motor vehicles.” He felt that it was inadvisable to increase the number of organizations under the Commanding General, SOS, and that future improvements in the organization could be made within the existing structure as effectively as ender any new organization operating under a different name.

Any change from the present organization, he believed, could be justified only if the efficiency of the Army as a whole would thereby be increased, and he could find nothing in the proposal that promised this result. Furthermore, he argued that, if the new corps were created without change in management and operating personnel, the only result would be a change of insignia; if personnel were also changed, it would mean the elimination of people who had worked intensively on motor transport problems for the past two years. He concluded with the declaration that he did not feel the present organization had failed, and therefore he could not approve plans to create a separate motor transport corps. Two days later, having reflected further on the matter, General Gregory sent another memorandum to the Commanding General, SOS, emphasizing the duplication of overhead that would result from the establishment of a new service.36

Whether the arguments of The Quartermaster General were persuasive, or whether a counterproposal was presented to focus attention of the SOS elsewhere, interest shifted once more from the creation of a separate motor transport corps to the transfer of maintenance responsibility. This had been discussed for some time, and there had been occasional talk about concentrating full responsibility for motor procurement either in the Ordnance Department or the QMC. Each service naturally felt that, if procurement and other responsibilities for motors were combined, it should perform the work because it was best organized and qualified to do so. At any rate, less than a week after General Gregory had submitted his second memorandum opposing creation of a separate motor

corps, SOS asked him to submit his reasons for believing that the Motor Transport Service should not be separated from the QMC and attached to the Ordnance Department.

General Gregory called attention to his two earlier memoranda on the subject and declared that it was his understanding that the principal reason for the proposal was “that the Ordnance repair activities and the Quartermaster Corps repair activities may be combined.” This he conceded might have some advantages, particularly in the armored divisions, but in the ordinary triangular division Quartermaster vehicles predominated. Moreover, transfer of the motor activities to the Ordnance Department, he felt, would result in the establishment at every post of another overhead organization, and “confusion already exists at a great many posts because of the change in the Quartermasters’ duties.” This change would add to the confusion. He insisted that a change at this time would require an undesirable period of adjustment. If, however, maintenance of vehicles were to be transferred, he advocated that the procurement and distribution of motor vehicles be left as a function of the QMC.37

The arguments of General Gregory did not prevail. The desirability of centralizing procurement as well as maintenance of automotive equipment was emphasized by a study being made by the Control Division, SOS. It surveyed the problems of the Tank and Combat Vehicles Division of the Ordnance Department and recommended centralization of all tank and automotive procurement in Detroit, a suggestion that was carried out immediately following the transfer of motor transport activities.38 On 17 July 1942, three days after General Gregory had presented his case, Headquarters, SOS, issued an order transferring motor transport activities to the Ordnance Department. The regulation which put the transfer into effect designated 1 August as the effective date.39

Despite the loss of functions to the Corps of Engineers, the Transportation Corps, and the Ordnance Department, the QMC ranked next to the Ordnance Department as the most important procurement service of the ASP. The Quartermaster General remained responsible for the procurement, storage, and issue of subsistence, petroleum and lubricants, clothing, broad categories of equipment, and all general supplies. These functions constituted the basis of a mission unusually broad for any single operating agency and involved many complex administrative problems.

General Reorganization After Pearl Harbor

When the United States entered the war, the supply mission of the QMC was administered by a headquarters office in Washington, which for a short time continued to be organized on a commodity basis, and a field organization, the most important components of which consisted of depots and market centers. The Quartermaster General was still under the direct supervision of the General Staff and, insofar as procurement matters were concerned, the Assistant Secretary of War, whose title by this time had been changed to Under Secretary of War. Because of pressures both within and without the office, the OQMG was soon to undergo a general reorganization.

Early in March 1942 the War Department was reorganized, and as a result the QMC came under the direct supervisory control of the Commanding General, SOS. Apparently no particular change was contemplated, however, in

the responsibilities and functions of the QMC and the other supply arms and services.40 While a change occurred in the top structure of the War Department, it did not directly affect the internal organization or operations of the supply services. Indirectly and powerfully, however, the functional organization of the SOS influenced the internal organization of the QMC.

The functional type of organization was diametrically opposed to the commodity principle. Instead of a vertical organization it offered a horizontal type wherein one function was assigned to a single unit of that organization. Thus, instead of a group of branches in a supply division, each concerned with one type of commodity from procurement to issue, a single procurement division would purchase all supplies bought by the agency, while a distribution division would distribute and issue such supplies. Such clear-cut delineation of responsibilities could be projected in an ideal, theoretical organization to prevent overlapping responsibilities which contributed to confusion and delay. In actual practice, however, the OQMG never achieved a purely functional organization.

To anticipate developments within the OQMG, the functional principle was frequently compromised. Divisions, such as the Subsistence and the Fuels and Lubricants Divisions, were frankly organized on a commodity basis. Even within functionally organized divisions, branches were established on commodity lines. The reorganization within the OQMG after Pearl Harbor resulted in the development of a hybrid functional-commodity type organization. Because of the speed with which the OQMG was reorganized, as well as misunderstandings of the functional principle, precise definitions of the responsibilities of divisions were not established. This resulted in considerable internal conflict which was further aggravated by clashing personalities.

Similarly, in theory, a sharp distinction was drawn between staff agencies, which developed plans and policies and specified procedures for their execution, and operating units, which carried them out. In the reorganization of the OQMG in March 1942, an attempt was made to differentiate between staff and operating divisions, but analysis of their functions reveals that responsibility for staff functions was often vested in operating units so that confusion resulted. Theory and practice were frequently in conflict. Despite the fact that the OQMG was undergoing a major reorganization, however, the QMC successfully achieved its part in mounting the campaign in North Africa in 1942 and subsequent campaigns.

The Control Division, SOS, exerted vigorous pressure from the beginning to promote a policy of conformity in organization throughout the supply services, primarily to facilitate control and liaison. Since the organization of staff activities immediately under the commanding general was logically functional, the main pressure was designed to force into line with SOS organization the activities of the technical headquarters as well as those of regional and field organizations. The correlation of functions between agencies on the two levels was designed to create well-defined channels through which SOS instructions on policy and procedure could be circulated and enforced, and to make possible more effective liaison on functional problems between units of the OQMG and the other supply services.

Within the OQMG a control group under Col. Harold A. Barnes worked closely with representatives of the Control Division, SOS. Several civilian experts who came from commercial organizations employing the functional principle were added about this time to the group. In general, they were advocates of

immediate and fundamental change in Quartermaster organization.41

On the other hand, criticism of the functional principle was usually voiced by commodity operators and executives who naturally defended a system to which they were accustomed. But the trend of developments was against the continuation of a purely commodity organization. Other government agencies with which the Corps had relations were organized functionally, and ease of communication would be promoted by a similar organizational arrangement in the OQMG. The business world, too, generally made use of the functional principle. According to The Quartermaster General, the OQMG would therefore have been reorganized gradually along functional lines even if pressure had not been exerted from the SOS.42

As a result of these pressures, the OQMG suddenly abandoned its traditional commodity-type organization. Within three weeks after the formation of the SOS, the OQMG was reorganized on a functional basis. There was little time for prolonged discussion. On 26 March General Gregory informed his division chiefs of the proposed changes and the allocation of office space in accordance with a planned move of the OQMG to new quarters in Washington.43 On 31 March the OQMG issued Office Order 84, which became the blueprint for organization and responsibilities throughout the war. In the five-day interval division chiefs had prepared organization charts and functional statements for their respective divisions, including each branch and section involved. This mass of data was turned over to the newly formed administrative control staff to be drafted into Office Order 84. As a consequence, some matters involving controversy were included, while others requiring further deliberation for their settlement, such as the establishment of deputies for administration and operations, were omitted.

The new organization provided for an administrative and advisory staff.44 Under this staff were grouped an Administrative Assistant to The Quartermaster General and the “staff” divisions of Budget and Accounting, Civilian Personnel Affairs, Military Personnel and Training, Defense Aid, Inspection, and Organization Planning and Control. A seventh staff division, General Administrative Services, was mentioned only in the specific statement of functions. Activities of this division—the successor to the former General Service Division—were not fully determined at this time, but most of the former activities of the Executive Office were shortly transferred to it, making the division responsible in general for administrative service activities in both the OQMG and the field.

Six “operating services” were provided for under the titles of Military Planning, Production, Procurement, Storage and Distribution, Service Installations, and Motor Transport. Except for obscurity on certain matters of common interest, the functions of the basic purchasing and distributing services were outlined as might be expected for services with their general missions. The title “Service Installations” was used to designate the agency supervising a number of special field installations or activities in the nature of services to the Army which had long been identified with the QMC. Actually it was a catch-all agency for this purpose, since it handled a group of miscellaneous activities, such as remount, memorial, field printing, and laundry, while at the same time it was a functional operating service, administering the activities of conservation, reclamation, and salvage, which were the final stages in the supply process. The

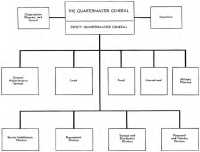

Chart 2—The Quartermaster Corps in the War Department: March 1942

interrelation of many of these activities, especially salvage, with functions of the other basic services was to constitute a problem that eventually demanded definition. Divisional supervision of the heterogeneous activities of Service Installations was necessarily rather loose and was never completely satisfactory.

Problems of Adjustment Under Office Order 84

The broad, functional responsibilities of the new staff divisions and operating services as outlined in Office Order 84 conformed, insofar as possible, to those of corresponding staff units. Although the statements defining these responsibilities were relatively clear-cut and distinct, they did not agree in all cases with those of specific functions allocated to divisions. These, in many instances, had been incorporated verbatim from the functional statements submitted by officers who were interested in the broadest possible statement of their responsibilities. The chiefs of many divisional and branch units were naturally reluctant to surrender traditional responsibilities, yet they were eager to obtain others. The resultant overlapping of responsibilities provided fertile ground for conflict because the functional statements could often, with justification, be used to prevent the transfer of activities and personnel or to dispute the jurisdiction and policies of other chiefs with similar responsibilities.

Within a few days of the announcement of the reorganization it was evident that an impasse existed. Most of the areas of cooperative or overlapping responsibility between divisions were the subject of protracted discussion, and few if any of the suggested transfers of units were taking place. By the second week in April this situation had progressed to the point where The Quartermaster General felt constrained to address the directors of the several functional agencies, calling attention to the need for full cooperation between all units and individuals and the necessity for resisting “the tendency to build up autonomous organizations” within the OQMG.45 He re-emphasized that the functional plan was in his opinion necessary to “meet the organization” of the SOS. The organization being installed was by no means perfect and would require many adjustments. Such duplications of effort as could be tolerated, he added, would be mainly “in the nature of a double check,” as, for example, on the validity of requirements data. It was several months, however, before the problem of extensive duplication of activities resulting from the failure to transfer and consolidate units came to a head.

Although General Gregory was well aware of the duplications that existed, he preferred to restrain the organization planners in the Organization Planning and Control Division who were eager to carry out their theories at once and eliminate all maladjustments immediately. He felt that he had to exercise patience and to tolerate duplications in the interest of maintaining continuity of operations in the Corps, for these changes were being made at a time when the QMC was under heavy and increasing pressure to supply the troops. The Quartermaster General observed that where two groups were vested with the same responsibility, they frequently prodded each other into action. When the opportune moment presented itself, he could and did direct the necessary adjustments.46

Among the many individual maladjustments arising from the wording of Office Order 84 or from the organizational alignments created by it, the most immediately critical were those relating to the organization and conduct of the procurement and production functions of the Corps. Ambiguities in responsibilities for the estimation of requirements, purchasing, and

production controls were typical of the general indefiniteness regarding activities of common interest to two or more functional units. The details of the procurement and production organization and purchasing procedure, as well as consideration of methods and organization for requirements, came immediately under examination and criticism. While decisive action on requirements was held in abeyance pending the development of a need for rigid scheduling and control of supply, a number of surveys reviewing the Quartermaster procurement organization were made by the OQMG, the Control Division, SOS, and other government agencies.

Production expediting was one of the areas of conflicting jurisdiction. The production-expediting functions of the former Production Branch in the Planning and Control Division were turned over to the Procurement Service ostensibly in recognition of the necessity for blending this phase of production control with the purchasing program. Actually, very few of the officials and employees of the Production Expediting Section were relinquished when this transfer occurred. They remained with the Production Branch and became a part of the Production Service when it was created, in part by absorption of most of the Requirements and Production Branches of the former Planning and Control Division. The Production Service therefore had the only sizable and qualified group available for expediting duties. It was charged with providing a consulting service for the Procurement Service on production problems. As a result, depot personnel continued to call directly upon it for help in solving production problems. There were ample grounds for the view of some executives that the Production Service constituted in reality the agency responsible for expediting production. There was equally good reason for the Procurement Service to resent interference with its supervision of field activities and encroachment upon what it considered its proper functional sphere granted by specific order.47

Procurement functions offered another fruitful source of conflict between the Procurement Service and the Storage and Distribution Service. When the old Supply Division was broken up as a result of the functional reorganization of the OQMG, the purchasing sections of its commodity branches formed the basis of the newly created Procurement Service. The remnants of these commodity branches were absorbed by the Storage and Distribution Service. In addition, the Subsistence Branch of the former Supply Division and the Fuel and Utilities Branch of the Executive Office also became part of that service. It was only natural that resistance to the transfer of procurement activities should come from units of the former Supply Division lodged in the Storage and Distribution Service. Office Order 84 made the Procurement Service responsible for the purchase of all supplies for the Quartermaster Corps except those for motor transport. A survey in the fall of 1942 disclosed, however, that the Storage and Distribution Service was still supervising purchase in several major categories,48 such as subsistence, and gasoline and lubricants purchased under Treasury or Quartermaster contracts.49

Adjustments between the Procurement Service and the Storage and Distribution Service were also hampered by the very broad view of

the latter’s mission entertained by its director. He considered that the service was intended to be the real control agency and summarized his views as follows:

The Storage and Distribution Service computes the requirements of the Army in Quartermaster items and transmits these requirements to the Director of the Procurement Service who does the actual purchasing. The Storage and Distribution Service also furnishes the Director of Procurement with the desired distribution of the items to be purchased. Once the items have been procured and accepted, the Procurement Service has no further responsibility. From this point on the Storage and Distribution Service is responsible for the receipt of these items at depots, their storage, classification, and safeguarding, and their subsequent issue to troops.50

The computation of requirements and supply control furnished still another area of disputed jurisdiction. Under Office Order 84 the Storage and Distribution Service computed the requirements actually used as the basis of Quartermaster procurement. On the other hand, the Requirements Division of the Production Service arrived at independent calculations for inclusion in the long-range Army Supply Program, since it was responsible for calculating all long-term requirements and translating these into terms of raw materials and production facilities. The two sets of figures thus derived proved mutually unacceptable to the services concerned. In effect, the conflict present under the earlier OQMG organization, in which there had been repeated difficulty in reconciling data submitted by the Planning and Control Division with that of the commodity branches, and in persuading the staff and operating agencies to accept each other’s figures, was thus preserved.51

Readjustments in 1942

These maladjustments provoked a re-evaluation of the basic organization of the OQMG in the summer of 1942. The first definite recommendation for modification of the Quarter master procurement organization was offered in May by the Control Division, SOS. At the request of The Quartermaster General this division had attempted to appraise the efficacy of the reorganization of the OQMG which occurred in March. For this purpose it employed the services of Mr. R. R. Stevens of Montgomery Ward and Company52 who proposed certain organizational changes.

His general conclusion was that the reorganization had been in the right direction but had not gone far enough in coordinating related activities and in decentralizing procurement operations. He asserted that there was no justification for the existence of separate Production and Procurement Services, since the production problem confronting the Corps was a relatively minor one.53 He further recommended that planning, production, and the programming of requirements be consolidated with the procurement organization in a supply division and that such general planning and controls as were needed be placed on a staff basis within that organization. Distribution functions were also to be included in the proposed supply division as were research and developmental activities. Actual procurement and distribution was to be decentralized to commodity branches in the field, the chiefs of which would be in no way responsible to the commanding officers of the depots but would be responsible to the director of the supply division.

Obviously a large part of these recommendations ran counter to Quartermaster experience and particularly to the centralized procurement system that the Corps had been developing since World War I. Although the proposal for field commodity branches was not accepted, there was nevertheless a trend toward decentralizing procurement. Decentralization was persistently advocated by the ASF during the war and some steps were taken in that direction by the Corps.54 Generally speaking, however, centralization remained the characteristic of Quartermaster procurement operations.

The proposal to unite research and procurement activities was rejected, although the character of Quartermaster research naturally demanded that it be correlated closely with current procurement and industrial management activities of the Corps as well as with production planning. During World War I, developmental activities had been thoroughly submerged in various commodity branches of the office, a mistake that those who were aware of the growing importance of research in the QMC were determined not to repeat. On the other hand, the recommendation to unite production and procurement in one division was accepted by the OQMG.

Immediate action, however, was not taken on these matters. In part the delay in settling the outline of procurement organization was due to consideration of a number of comprehensive surveys of procurement administration and policies which were being conducted by or in conjunction with higher authority. Two of these surveys, the so-called Cincinnati and the New York Field Surveys, were studies of regional activities in the areas indicated. Concerned mainly with integration of War Department procurement operations, they produced only incidental observations on the organization of purchasing and production in the technical services.

In the meantime, the basic steps in Quarter master procurement became the subject of another study with primary emphasis placed on the process rather than the organizational structure. It was undertaken during the summer of 1942 by a representative of the Bureau of the Budget, Spencer Platt, with the aid of members of the OQMG and SOS control staffs and did make thoroughgoing recommendations directly applicable to Quartermaster activities.55 This survey undertook a complete analysis of all OQMG functions relating to procurement. A work-flow study was submitted which showed how a commodity item was handled through the various stages of work, including product development, computation of long-term requirements, procurement planning (scheduling of purchases and production), resources analysis (computation of the availability and requirements of raw materials and plant facilities), purchasing, and production expediting. Urging recognition of their control or staff nature, the Platt Report called for the transfer of all production planning and resources-analysis activities either to the Procurement Service as a staff branch or to the Military Planning Service. This was the only specific proposal for realignment of organization growing out of the survey.

Primarily the Platt Report was concerned with the consolidation of functional activities in several important fields relating to procurement and the adjustment of responsibilities between divisions in order to promote better control and more effective operations, particularly in relation to the vital matter of requirements. It recommended that all research and developmental work at the OQMG be centralized in the Product Development Branch of the Production Service. While Office Order 84 had

placed general functional responsibility for research in this service, it had failed to provide for the transfer to it of the research units established in the commodity branches of the former Supply Division. Duplication and conflict resulted. For example, when the Clothing and Equipage Branch was transferred to the Storage and Distribution Division, it retained intact its own research organization.56

The Platt Report specifically called for the transfer of all fiscal activities to the Fiscal Division. Virtually no change in the status of these activities had taken place, though a recent order had provided for the progressive consolidation of the fiscal accounting units under the Fiscal Division. It did not touch directly the work of the fiscal estimating units in the commodity branches though it emphasized that “the Chief of the Fiscal Division represents the Quartermaster Corps in securing the necessary funds to carry out the plans, programs, and operations of the Corps.”57

After noting the reluctance of units of the former Supply Division to relinquish their procurement functions, the Platt Report recommended that all purchasing be placed forthwith in the Procurement Service. It further recommended that the Requirements Division take over the translation of the supply program into monthly requirements and that these be used directly by the Procurement Service for purposes of procurement planning, thereby eliminating the processing of a separate request or “plan” for purchase. It suggested, however, that to make the procedure effective the Requirements Division should be encouraged to develop closer liaison with the Storage and Distribution Service, thus avoiding the acceptance of unrealistic figures. The Platt Report was emphatic in its insistence that the current separation of procurement planning and procurement was a definite impediment to proper purchasing operations.

By the middle of the summer of 1942 it was evident that a more or less fundamental reorganization of OQMG activities was in the offing. Among the surveys made, only one58 had raised the question of the desirability of returning to a commodity-type organization. When reorganization of the OQMG came up for definite consideration in June, the majority of the Quartermaster organization planning staff was convinced that the functional plan of organization was basically sound, but that some of the existing functional responsibilities needed clarification.59 The need for developing adequate coordination between the several functional activities was recognized as imperative, for it was clear that the clash of personalities and competition for functions among certain of the division and branch chiefs was actually imperiling the successful execution of the supply program.

A further important factor dictating against reconsideration of the decision to perfect a functional system was the determination on the part of The Quartermaster General and others to merge the activities of motor transport, subsistence, and other large self-contained commodity units into the functional organization or at least subject them to a high degree of functional supervision. This determination seems to have been due in part to the desire to present an integrated Quartermaster organization in answer to proposals for the transfer of certain functions to other jurisdictions. The creation of a separate motor transport service was then under consideration and the QMC was also confronted at this time by agitation

for the assumption of all government food procurement by the Department of Agriculture.60

The arguments for a return to a commodity basis were definitely rejected and this form of organization was never officially under consideration again during the remainder of the war period.61 As time went on, the further disadvantage of risking fundamental change in the midst of intensified military activities had to be considered. The reconsideration of OQMG organization begun in May was resolved in favor of retention of the functional system.

The OQMG issued Office Order 184 on 31 July 1942. It attempted to solve the problems that had arisen within the general framework of the functional organization established in March. It sought first of all to correct the most obvious deficiency of the earlier order by recognizing that the supply planning and control functions were in theory as well as in fact “staff” in nature. An effort was therefore made to group all of the existing activities relating to control of supply into a single agency, a new Military Planning Division, which was expressly designated a staff agency.62 This division combined the functions of the former Military Planning Service and of the Production Service, except for a residue transferred to the Procurement Division.

Office Order 184 also combined production control and procurement. As late as the summer of 1942, however, this question had not been settled. At a staff conference in June many Quartermaster officials urged the continued maintenance of production control as a separate staff activity rather than its consolidation with the purchasing organization.63 The fact that procurement activities were tending to be decentralized more and more to the field ruled out their administration by a staff agency. They could be handled more appropriately by the agency directly supervising depot activities. The order therefore transferred the Facilities Section and the supervision of the regional procurement planning districts from the Production Service to the Procurement Division. Thereafter technical control and coordination of field purchasing and production activities remained a responsibility of the Procurement Division. It developed its own production service program, which was not limited to the survey of facilities and production expediting but included activities in reference to priorities, the handling of labor questions, and financial aid to contractors, all of which were important in overcoming production difficulties.

One other important change in the reassignment of functions was made in July. This involved a more extensive consolidation of procurement activities than had taken place in March. Thus, the responsibility for the procurement of all pier, warehouse, and materials-handling equipment assigned to the Corps was vested in the Procurement Division. Its responsibility for the purchase of all general supplies was reaffirmed, and all procurement functions of the Service Installations Division were transferred to it. Furthermore, it became responsible for the procurement of gasoline and lubricants. On the other hand, the transfer of all subsistence procurement to the division as directed by the order was never accomplished.64

Chart 3: Office of the Quartermaster General, 31 July 1942

The changes instituted in OQMG organization in the summer of 1942 represented the last major reorganization affecting functions during the war. Later changes were largely in the nature of refinement, and administrative planning was occupied primarily with improving coordination between divisions and creating a better organization for management of OQMG activities from the top. The functions and responsibilities of divisions, particularly with reference to the cooperative responsibilities of several of them in handling specific phases of supply activity, were defined more exactly in basic office orders in an effort to make lines of authority clear and to prevent duplication of activities and confusion in command relationships with the field. In addition, the divisions in cooperation with the Organization Planning and Control Division drafted more specific statements of functions. Specific instructions were also drawn up, covering basic procedures and allocations of responsibility on general and special phases of work. Thus, procedures governing the cooperative handling of lend-lease transactions by the International Division and the operating divisions were precisely defined. Illustrative of this same trend was the clarification of procedures and the exact allocation of responsibilities for handling various phases of the Controlled Materials Plan.65

The functional reorganization imposed a severe burden upon The Quartermaster General, in that chiefs of twelve separate .divisions were reporting directly to him and taking up time he needed for more important matters of general policy. He solved this problem in the fall of 1942 by delegating supervisory responsibility to two deputies, each with responsibility for directing and coordinating the activities of six divisions.66 Generally speaking, functions of a staff character were placed under the Deputy Quartermaster General for Administration and Management,67 while those most closely associated with actual supply activities came under the Deputy Quartermaster General for Supply Planning and Operations.68

Each Deputy Quartermaster General had definite authority to make decisions concerning the activities of the divisions under his supervision. However, the Deputy Quartermaster General for. Administration and Management was also given authority to coordinate important matters of administration in all echelons by the provision that division heads take up with him all questions involving administrative activities and personnel requiring the decision of The Quartermaster General.

To help him discharge his responsibilities, a small staff of specialists was organized, the members of which were designated “Executive Assistants to the Deputy Quartermaster General for Administration and Management.” Attached for administrative purposes to the Organization Planning and Control Division, they were selected particularly for their ability to solve problems resulting from the recent changes in the organization and distribution of functions. For example, the transfer of motor transportation to the Ordnance Department on 1 August 1942 required an expert in this field to assist in the redistribution of functions between the two agencies. Similarly, relationships between the Corps and the newly organized service commands69 required that an expert be appointed to help coordinate policies and procedures of the OQMG with functions of service commands as established by Headquarters, SOS. The executive assistants conducted studies and investigations of matters assigned to them by the Deputy Quartermaster General and prepared

recommendations for action to insure the proper determination, interpretation, and administration of new policies and procedures.

Evolution of Functional-Commodity-Type Organization, 1943-45

Despite the efforts made in 1942 to transform the Quartermaster administrative organization from a commodity to a functional system, the OQMG was never organized along purely functional lines. Instead it was an organization that consisted of both functional and commodity divisions. The commodity divisions handling the procurement and distribution of subsistence and petroleum products were outstanding exceptions to the general pattern of functional organization.

Fuels and Lubricants Division

A commodity unit, ostensibly responsible for the procurement, storage, and distribution of petroleum supplies, had existed since 1920 within the Supply Division. While in theory it was responsible for the control of petroleum products, in actual practice such operating divisions as Transportation and Construction performed almost all petroleum functions except the coordination of requirements. In March 1942 an attempt was made to divide petroleum responsibilities along functional lines between the Director of Procurement and the Director of Storage and Distribution. The latter was reluctant, however, to transfer the Fuel and Heavy Equipment Branch, as the unit was then called, to the Procurement Division despite the recommendations of the Organization Planning and Control Division in its survey of the problem.70 The survey contended that the branch was a procuring organization with no storage or distribution function.

Although Office Order 184 lodged responsibility for the purchase of fuels with the Director of Procurement, the petroleum-procurement situation remained confused in the fall of 1942. The Storage and Distribution Division was issuing directives to the Procurement Division for the purchase of petroleum products for task forces. All supply services in the SOS, many of them in direct competition with one another, were procuring various petroleum products. The Navy also was purchasing petroleum products for the Army, and practically all the ports of embarkation were individually directing procurement of petroleum products in which they were interested. Such diversity of procurement might be permitted in peacetime, but it was not feasible when the country was faced by the exigencies of wartime markets.

The necessity for consolidating and centralizing petroleum procurement led to the establishment of a Petroleum Branch in the Procurement Division in December 1942.71 By the following summer growing military needs, including unprecedented demands for packaged fuels and lubricants, resulting from the invasion of North Africa, required integrated staff work on the part of the services. Petroleum had become so important that it aroused the active interest and cooperation of the Commanding General, ASF, who proceeded to reconstitute the entire Army petroleum organization by creating in the OQMG a new Fuels and Lubricants Division.72 It was a thoroughly integrated commodity organization which handled the procurement, storage, and issue of petroleum products as well

as research and developmental work in reference to containers and equipment. Since the Director, Military Planning Division, contended that all research on Quartermaster items should be concentrated in the Research and Development Branch of that division, considerable friction developed initially in this field.73

The Fuels and Lubricants Division was unique in that it not only retained all the operating responsibility it had had prior to that time as the Petroleum Branch in the OQMG, but it also acquired staff activities; that is, with certain specified exceptions, The Quartermaster General became responsible for the performance of all staff functions necessary to the discharge of the operating responsibilities either assigned or subsequently delegated by Headquarters, ASF, to the OQMG.74 In addition, the director of the division acted as deputy to the Commanding General, ASF, in his capacity as a member of the Army-Navy Petroleum Board (ANPB), so that in this instance the division operated on the level of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Subsistence Division

The Subsistence Division constituted another exception to the general pattern of functional organization. Until 1912 the Commissary General of Subsistence had always been independent of The Quartermaster General. Although the Subsistence Department was merged with the QMC in that year, its tradition of independence lingered. Subsistence had for many years been organized as a commodity branch, and its personnel insisted that it could function efficiently only on a commodity basis. At the time of Pearl Harbor it was located in the Supply Division. When the OQMG was reorganized functionally, it was transferred intact as a commodity branch to the Storage and Distribution Service (later Division). It refused to adopt an internal organization which would lend itself to the functional system, and it resisted all attempts to transfer the functions of subsistence procurement or research to the appropriate functional divisions.75

In the summer of 1942, for example, responsibility for the research, development, standardization, and adaptation of all types of Quartermaster equipment, except those utilized for petroleum products, was vested in the Research and Development Branch of the Military Planning Division. Despite this assignment of responsibility, subsistence research continued to be conducted by the Subsistence Branch and the Subsistence Research Laboratory,76 which was formally connected with the OQMG only through the commanding officer of the Chicago Quartermaster Depot. In the past there had been some lack of coordination and some duplication of activity, but on the whole the two units had worked in harmony and with good results. Subsistence research continued to be handled by these units until the close of 1942.

At that time the OQMG attempted to clarify this situation by reaffirming the responsibility of the Military Planning Division for all research.77 This division was responsible thereafter for assigning projects to, and directing the technical activities of, the Subsistence Research Laboratory. The chief of the laboratory remained under the authority of the

commanding general of the Chicago Quartermaster Depot with respect to all activities, except those relating to the technical aspects of subsistence research. A Subsistence Research Project Board was also created at this time. One of its duties was to “initiate projects for research and development on any subject which it deems of benefit to Army subsistence.” The vice chairman and one other of the members appointed to this board were from the Subsistence Branch. Thus, although the actual responsibility for research and development in this field rested with the Military Planning Division, it was possible for the Subsistence Branch through its representation on the new board to maintain an active interest in subsistence research.

In pursuance of the functional plan of organization, Office Order 184 directed the transfer to the Procurement Division of all functions of the Subsistence Branch related to procurement and all personnel engaged in procurement activities. At the same time, however, the order also provided that “no physical movement of personnel of the Subsistence Division will be made without further approval of The Quartermaster General.” Several problems were involved in this projected move. At the outset there was the question of the feasibility of splitting purchase from distribution of subsistence. The entire operation, at least for perishable items, was a highly synchronized one, performed through the specialized machinery of the market center system. Secondly, the operation was recognized as primarily one of commodity procurement, with distribution accomplished more or less incidentally and directly from the markets where the food was purchased to using components of the Army, without the use of depot or other permanent storage in transit. Certainly the projected division of responsibilities would have meant the transfer of virtually the entire Subsistence Branch organization to the Procurement Division. Such a transfer had in fact been under consideration earlier, but was rejected be- cause, in the opinion of The Quartermaster General, the move would have been of doubtful effectiveness in promoting cooperation among personnel within the OQMG.78

The major part of Quartermaster activities relating to the handling of subsistence in the Army and its special problems continued to be centralized under the Subsistence Branch of the Storage and Distribution Division until the summer of 1944. Since subsistence always accounted for the major portion of Quartermaster procurement, the Subsistence Branch was actually doing more purchasing than the Procurement Division. In May the branch was established as a separate division79 under a director who represented The Quartermaster General in all interagency contacts pertaining to the purchase, supply, and preparation of food. He also directed all Army programs connected with preparation and service of food. Thus the Subsistence Division continued as a commodity organization within the generally functionalized organization of the OQMG.