Chapter 3: The Development of Army Clothing

In any discussion of wartime scientific achievement it is inevitably the spectacular—jet propulsion, new explosives, radar—which obtains the most publicity. This may obscure but by no means diminishes the importance of the research done by the Quartermaster Corps in cooperation with industrial and university laboratories in developing those items of clothing which contributed to the physical and mental well-being of the soldier in World War II.

Organization for Product Development

Quartermaster research activities were centered in the Supply Division at the beginning of the national emergency in 1939. Two units of that division—the Standardization Branch and the Clothing and Equipage Branch—were active in the development of new items of Quartermaster clothing and equipment and in the revision of specifications.1 The Standardization Branch, the heart of which was the Specifications Section, was responsible for supervising the development, preparation, and standardization of specifications for all articles provided by the Quartermaster Corps. This supervision meant checking and clearance rather than the direction of an active program of coordination. The branch also handled administrative details for the Quartermaster Corps Technical Committee (QMTC), which effected coordination among all interested branches of the Army during the development and standardization of types of clothing and equipment for which the Corps had responsibility, and the preparation and coordination of specifications. Lt. Col. Letcher 0. Grice was chief of the Standardization Branch and executive officer of the committee. The Clothing and Equipage Branch was under the direction of Col. Robert M. Littlejohn, later to become Chief Quartermaster of the European Theater of Operations (ETO). Although primarily concerned with procurement, this branch had been accustomed to take a dominant part in the design of items within its province and continued to be active in developmental work.

In the emergency period Quartermaster research was confined, as heretofore, largely to correcting deficiencies in items as pointed out in the annual surveys of equipment made by the chiefs of branches of the Army. Occasionally upon request new items were developed. Quartermaster research did not become an activity in its own right, however, until the end of 1941. This development resulted from the mounting international crisis, which by 1940 had forced the United States into a vast defense program, including the dispatch of a greatly enlarged garrison to Alaska.

The Alaskan clothing list, revised to some

extent in 1928, had remained almost unchanged until 1940. Both the Clothing and Equipage and the Standardization Branches were engaged in 1940 in revising this list and in developing and procuring suitable cold-climate clothing and equipment. A series of meetings on the problem emphasized the need for an organization, unhampered by problems of procurement, storage, and distribution, to study cold-climate equipment. As a result, Brig. Gen. Clifford L. Corbin, chief of the Supply Division, authorized the establishment of a new Cold Climate Unit in the Standardization Branch late in 1941.2 Quartermaster wartime research and developmental activities stem from these beginnings.

Lines of responsibility for the details of the development of items of clothing and equipment necessarily remained somewhat flexible. Both the Clothing and Equipage Branch and the Standardization Branch were acquiring industrial specialists and expanding rapidly to meet their responsibilities.3 There was a certain amount of duplication of organization and functions which was of minor consequence as long as the two branches remained in close touch within the same division under chiefs who were in harmonious relationship. The prime objective was to get the work done, and consequently specific problems were handled by personnel of either branch as the qualifications of individuals dictated.

The reorganization of the OQMG along functional lines in March 1942 altered this situation. The Supply Division was broken up. The Standardization Branch, absorbed by the new Production Service, became the Product Development Branch within the Resources Division, and was headed by Lt. Col. Georges F. Doriot. At the same time the Resources Division also absorbed the Production Branch of the Planning and Control Division, thus merging in one organization the problems of production, materials conservation, and design. This consolidation gave recognition to the fact that product development and production problems were closely associated. The Clothing and Equipage Branch, which kept its own research organization intact in the transfer, became a branch in the new Storage and Distribution Service.

Two distinct organizations in the OQMG, rather widely separated from a control standpoint, were now performing essentially the same functions because this divided responsibility was not clarified during the process of reorganization. The conflict was presently resolved by the adoption of a recommendation made in the Platt Report to the effect that “all design and development work at headquarters, OQMG, should be centralized in Product Development Branch; such work being carried on now in Storage and Distribution Service should be transferred to Product Development.”4 The Production Service had made good its claim to jurisdiction in this field.

Responsibility for product development was further clarified in the second reorganization of the OQMG at the end of July 1942. The Military Planning Division absorbed the Production Service, taking over its organizational units intact. Its mission was declared to be, in part, to “develop Quartermaster items to meet changing needs and conditions.”5 The Resources Division, with Colonel Doriot continuing as its

chief, became the Research and Development Branch of the new Military Planning Division. Quartermaster research with some exceptions was now centralized in the Research and Development Branch, which continued to be the chief organization for product development in the OQMG during the remainder of the war.

A broad assignment of responsibility was made to the Research and Development Branch. It initiated action to insure continued practical development of Quartermaster equipment; approved all specifications for Quartermaster items; ascertained problems of production and materials, recommending solutions; and supervised conservation work as well as activities in the Corps concerned with the operations of the Controlled Materials Plan. In collaboration with other divisions of the OQMG, the Research and Development Branch prepared the Master Production Schedule and translated schedules for end items into requirements for raw materials. It coordinated the testing activities of the Corps, represented the OQMG on the technical committees of other arms and services, and served as the executive office of the QMCTC. The products sections of the branch had the primary responsibility for the development of specific items assigned to them. Although a number of organizational adjustments were later made within the Research and Development Branch, the organization for the development of Quartermaster items of clothing and equipment had, by the end of 1942, taken on a more or less fixed form for the duration of the war.6

While in theory all research activity of the QMC was centralized in the Research and Development Branch when the OQMG was reorganized along functional lines after March 1942, in practice this centralization took place slowly and was not completely accomplished during the war. For many months there was friction between the Subsistence Branch of the Storage and Distribution Division and the Research and Development Branch of the Military Planning Division over responsibility for research in subsistence and in the packaging of subsistence. It was the end of 1942 before this difficulty had been settled to the satisfaction of both divisions. Responsibility for research in packing was never vested in the Military Planning Division but remained with the Storage and Distribution Division throughout the war. Similarly, when petroleum procurement for the Army was centralized in an integrated commodity organization in the OQMG called the Fuels and Lubricants Division, that division was also given responsibility for the development of containers and petroleum equipment despite the contention of the director of the Military Planning Division that all research concerning Quartermaster items should be concentrated in the Research and Development Branch.7

The Research and Development Branch coordinated the research activities of all QMC agencies in the field. Notable among these were four of the Quartermaster procuring depots—Boston, Philadelphia, Jeffersonville, and Chicago. Boston specialized in footwear; Philadelphia in clothing and textiles; Jeffersonville in mechanical items, webbing, tentage, and tentage textiles; and Chicago in subsistence. In the years before the national emergency, the larger part of such research work as was done by the QMC was actually conducted at these depots, or by private manufacturers cooperating under their direction. Problems of equipment design, presented to the Corps from the using forces, were ordinarily cleared through the OQMG and referred to the appropriate depots for recommended solution. The Philadelphia and

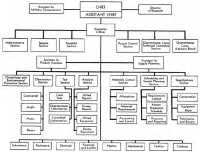

Chart 5-Research and Development Branch, OQMG: 16 June 1944

Jeffersonville depots maintained manufacturing plants, producing many of the items within their respective fields. These two depots contained quality-control laboratories which tested for specification purposes samples of items under procurement taken from the production line. In these laboratories, too, a certain amount of experimental work was carried on to improve existing items and develop new ones.8

All the varied activities of the depots were, of course, greatly expanded with the national emergency. The facilities of the Philadelphia and Jeffersonville laboratories were enlarged and modernized. In the vast developmental program incident to the preparation of suitable clothing and equipment for the wartime Army, they became a leading reliance of the QMC. Even before the great expansion of the Army, the Philadelphia Depot was engaged in a considerable variety of research and developmental projects in clothing and textiles. By August 1942 it was conducting studies and tests ranging from the water absorption of resin-coated fabrics to the reconditioning of World War I buttons. At the same time the Jeffersonville Depot was working on a number of projects looking toward the substitution of more available materials for strategic metals in Quartermaster items, the improvement of tentage duck, the study of rot- and mildew-resistant compounds, and the improvement or initial development of a number of duck and mechanical items. In September 1942 the Boston Depot reported activity on a number of projects for the improvement of the design of the service shoe as well as studies for the conservation of rubber in the arctic overshoe and the jungle boot. Such projects are illustrative of the research activities pursued by the depots—the prime agencies of the Corps in meeting its basic responsibility of supplying the Army.

If the Research and Development Branch of the Military Planning Division had difficulty in securing recognition in the OQMG of its responsibility for research, it also encountered opposition from the depots. Like other long-established field agencies in any widespread organization, they tended to generate their own esprit de corps, their own local loyalties, and their own jealously guarded prerogatives. In connection with developmental work they had over a period of years built up a tradition of semi-independence, which was little disturbed during the first years of the emergency. When the research and development organization within the OQMG began to take on final form, however, it started to assert control over the research activities of the depots.

Full coordination was not secured without some pressure. In May 1942 the depots were first required to submit to the OQMG regular monthly reports showing the status of all their projects.9 A few months later information in the OQMG on the research activities of one of the depots was still very meager. It was necessary for The Quartermaster General to reiterate that responsibility for “supervising and coordinating all research, development and engineering of Quartermaster supplies and equipment” was vested in the Production Service. To secure better coordination he soon directed that all depot research and developmental projects be submitted to the OQMG for approval before work was started on them.10

The depots had traditionally written many of the specifications for the items which they procured and had a tendency to take over this function more or less completely. The responsibility of the Research and Development Branch in this respect was now underscored. It was emphasized that this office would “furnish recommendations where necessary on specifications to be written by the depots since this office is in closer contact with the varying needs of different sections of the Army and with the changing availability of materials and facilities.”11 Even emergency specifications were to be submitted to the central office for concurrence.

A policy of making frequent visits to the depots to discuss problems, the submission of regular depot reports, and the approval of research projects and emergency specifications by the OQMG brought a closer integration of the research activities of the depots with the Quartermaster program as a whole and made the organization into a more effective working team. The control of the Research and Development Branch over depot research was further strengthened in the autumn of 1943 by an order which specifically made the assignment of projects to, and the direction of technical activities in, all Quartermaster research laboratories “the direct responsibility of the Military Planning Division.”12

The official QMC field testing agency was the Quartermaster Board, which conducted tests at the request of the Research and Development Branch. Created by direction of the Chief of Staff, U.S. Army, in 1934 at the Quartermaster School in Philadelphia, this board was re-established in 1942 at Camp Lee, Va., the chief training center for the QMC during World War II.13 Its president was directly responsible to The Quartermaster General in all technical matters. While the Quartermaster Board had been established under a broad charter, its chief activity became that of field testing clothing and equipment. Under Col. Max R. Wainer, director of the board, testing of various new items began shortly after the board moved to Camp Lee and increased rapidly thereafter.

Field testing, as done by the board, was not intended to be a substitute for laboratory testing but rather its complement. Field testing was divided into two main groups, normal and expedited testing. In normal testing items were used by personnel in the performance of regular daily activities. In expedited testing the life span of an article was compressed into a fraction of its normal expected life. Expedited testing was used when time was a major consideration, while normal testing permitted a finer degree of accuracy.14

Both special and fixed installations were used for testing items. To test various types of mechanical devices, where a high degree of operating skill might be required and the utmost control be essential, special installations which could be dismantled at the end of the test were set up for individual tests. On the other hand, fixed installations, such as the shoe test track and the combat course,15 were set up at the Quartermaster Board for many of the tests on footgear and clothing. By the use of these proving grounds definite patterns of wear could be established. Still another method was to test under controlled conditions. Thus, a principal test method involved the use of many samples of clothing and equipment items by troops engaged in controlled activities in the field. In this type of testing actual tactical problems were devised and were executed by trained units of men under conditions designed to duplicate realistically field conditions to which the items under

consideration might be subjected. Another method, invariably supplemented by other approaches, employed considerable numbers of samples, and personnel engaged in their normal duties. Personnel of the regular training regiments at Camp Lee were equipped with the materials undergoing test, and observers and recorders were attached to such units during the test period.

Another important QMC testing agency for clothing and equipment, established after the war began, was the Climatic Research Laboratory, at Lawrence, Mass. This laboratory was first projected by Dr. Paul A. Siple, authority on the Antarctic, when he was temporarily employed by the Corps as an analyst of cold-climate clothing in the summer and autumn of 1941. He believed that the Corps, with its vast and increasing responsibility for clothing and equipping troops for service in varied climates, should have under its own control a fully equipped laboratory where extreme conditions of both cold and heat could be produced. There the techniques of the physiologist, the physicist, the textile expert, and the climatologist could be applied and the results synthesized to place the selection of clothing for any given environment on a really scientific basis.16 Dr. Siple believed such a laboratory was particularly essential inasmuch as physiological laboratories had not taken into consideration the effects of clothing in their studies of climatic stress. He was given carte blanche to organize the laboratory, although by agreement with the chief of the Research and Development Branch he was not obliged to operate the laboratory. Instead he was permitted to set up a companion climatology unit in the branch in which to work out more of his ideas.

While considerable time elapsed before the laboratory was eventually established, by March 1943 it had begun the testing of cold-climate clothing and equipment. Lt. Col. John H. Talbott of the Medical Corps, who had long been associated with the work of the Harvard Fatigue Laboratory, was appointed to take charge of the laboratory. Its work expanded rapidly. Later the Climatic Research Laboratory constructed a hot chamber where desert and jungle conditions could be simulated. The laboratory became the principal facility of the Research and Development Branch in the performance of such tests on clothing and equipment for climatic extremes as could be performed in a laboratory, though much testing of this nature continued to be done also in cooperating private laboratories.17

Testing of new items of Quartermaster issue by the Army service boards had long been part of the regular procedure leading to standardization. These boards were organizations set up by the chief of each technical service to test items that were developed, and such testing continued during the war. In addition, the Research and Development Branch was responsible for securing the collaboration of a considerable number of governmental and private agencies in this work. Governmental agencies which carried on laboratory work for the Corps included the National Bureau of Standards, the official government testing agency, which in normal times

Chart 6: Quartermaster Board Shoe Test Track

Chart 7: Quartermaster board combat course (1,700 feet)

was the principal reliance of the Corps for laboratory testing of materials, and the Textile Foundation, another agency in the Department of Commerce. The laboratory and reference facilities of the Department of Agriculture and the Department of the Interior also gave considerable assistance in the work of the Research and Development Branch.

The Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), established by executive order in 1941 for the purpose of assuring adequate provision for research on scientific and medical problems relating to national defense, was of great and steadily increasing assistance to the OQMG in its developmental work. Fundamental research problems were ordinarily presented to the OSRD through the War Department liaison staff which had been set up for such clearance in Headquarters, ASF. Through its National Defense Research Committee the OSRD made available the facilities of governmental, university, and industrial laboratories all over the country for the solution of scientific problems. Assisted by this committee, the Military Planning Division placed contracts with the laboratories considered most able to perform the desired research. In placing contracts the division also dealt directly with representatives of a particular industry or a university laboratory.

In addition, the Research and Development Branch had its own Advisory Board, composed of executives in various fields of research as well as outstanding scientists and explorers who were able either to contribute directly to the solution of specific problems or who headed organizations with scientific personnel whose services could be made available. This board was organized in the spring of 1942, when the product development organization of the OQMG was taking on permanent form under the direction of Colonel Doriot.

A number of university laboratories, specializing in various fields, were called upon for assistance in the development of equipment. By posing questions and problems and by analyzing reports, the Research and Development Branch guided its cooperating laboratories in the work to be accomplished. Among the university laboratories contributing to the results achieved, the Fatigue Laboratory of Harvard University was especially notable. When the war began this laboratory was under the directorship of Dr. David B. Dill,18 who was succeeded in 1941 by Dr. William Forbes as acting director. The laboratory had undertaken a broad program of physiological research, involving studies in all phases of the physiology of fatigue, including effects of heat, cold, and altitude on human efficiency. During the war it was engaged entirely on war research projects, nearly all of which concerned the OQMG. These included basic research on clothing principles, in particular the efficiency of Army clothing, as well as nutritional studies. Its program was integrated with that of the Climatic Research Laboratory at Lawrence and the Subsistence Research Laboratory at Chicago.19 As the new Climatic Research Laboratory came into action, work was divided between it and the Fatigue Laboratory. In general, practical tests of completed items were made by the Lawrence Laboratory, while research into the principles of design for clothing suitable to climatic extremes remained the function of the Harvard organization.

Valuable work in the physiological testing of Quartermaster clothing for climatic extremes was also performed by Dr. Lovic P. Herrington and his staff of the John B. Pierce Laboratory of Hygiene at New Haven, Conn. The Department of Physiology at Indiana University under

the direction of Dr. Sid Robinson also conducted laboratory testing of uniforms for hot climates. Assistance was given to the Research and Development Branch in the study of problems of fiber, yarn, and fabric properties by the Textile Laboratories of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, under the direction of Professor Edward R. Schwartz. Leather problems were analyzed. by the research laboratory of the Tanners’ Council located at the University of Cincinnati.

In wartime, as in peace, the Corps depended on private industry for a great part of its research and developmental work. In November 1940, shortly after the first considerable enlargement of the Army had taken place, there were some nineteen firms cooperating in eleven projects of the Supply Division. In January 1942 more than 200 business firms were reported as engaged in cooperative development of seventy-five different items, aside from motor transport, for the QMC. These firms included leaders in the fields of chemicals, rubber, textiles, clothing, leather goods, light metal products, chinaware, and others.20

Industry generally was eager, under the stimulus of war, to contribute its inventive genius, laboratory facilities, and technical skill to the solution of Quartermaster equipment problems. Many new products were regularly brought to the attention of the OQMG as offering possibilities in the way of meeting Army needs. As early as February 1941 the flood of such offerings had become so great that there was established a special Quartermaster Equipment Board within the Supply Division for the

purpose of passing upon new articles and proposed changes in design submitted by manufacturers and others. The OQMG also, through its varied technical staff, attempted to keep in touch with all pertinent technical advances in industry, and frequently inquired for samples of new materials or finished items which might have Quartermaster application.

When a new item was needed, or field reports indicated the necessity of an improvement in design, whole industrial groups were often called upon to offer their suggestions or to take up the necessary development with their own facilities. Thus, when a new stove, small and light enough to be carried in the rucksack, was needed for mountain troops, a meeting of the design engineers of nine of the leading stove manufacturers of the country was called at the Chicago Quartermaster Depot, and the problem was presented to them. When the QMC took over from the Ordnance Department the development of the liner for the new steel helmet, half a dozen manufacturers of plastics and other firms interested in the problem were brought into conference and asked to pool their resources in order to hasten the development and mass production of this badly needed item. When trouble with the burner of the M-1937 field range persisted in the field, the Coleman Lamp and Stove Company and the American Gas Machine Company, two of the leading firms in the development of gasoline-burning equipment, with the Ethyl Corporation, research authority on leaded gasoline, were asked to cooperate and produce a better burner.21

The Research and Development Branch dealt with industrial firms, as far as practicable, through committees and associations set up by the various industries for their common benefit. Many such associations were established during the war to handle the highly specialized problems growing out of the needs of the armed

forces. Conferences with such associations, at the call of the OQMG, were part of the regular routine of the office. Sometimes such an organization, with its member firms working on contracts for the same item, would take the initiative and call a conference to discuss and present to the QMC problems of production and suggestions for the improvement of designs.

The contributions of American industry to the development of Quartermaster clothing and equipment eventually became almost infinite in number and variety. They ranged from minor suggestions as to the design of a relatively simple piece of wearing apparel to the development, sometimes by a single firm, of a complicated mechanical item. Hundreds of industrial organizations in many fields of production aided, with consultant service, individual or cooperative design, or laboratory testing of the finished product, in the solution of the developmental problems of the OQMG.

Development and Standardization Procedure

The general procedure to be followed in the work of research, development, and classification of items of equipment for the Army was prescribed by AR 850-25. This regulation, as revised in 1943, stated in substance that research and development were functions of the technical services under the general direction of the Commanding General, ASF, or in case of Air Force items, of the Commanding General, AAF. Under established procedure a developmental project was initiated whenever a using arm decided that a given development was desirable. The using arm also formulated the statement of the military characteristics which the projected item was to possess. The development was then coordinated through the technical committee of the service charged with the procurement of that class of equipment. The procurement of experimental types was approved by the Commanding General, ASF, after which the necessary developmental program was prepared by the chief of the technical service concerned. Development was pursued in close liaison with the using arm. When experimental types had been developed and procured, they underwent engineering tests, conducted by the technical service, to determine their engineering soundness, and service tests, conducted by the using arms and services, to determine their suitability for service use. The developing service coordinated all tests to insure that they were comprehensive, without incurring delay or duplication of effort. Classification of the item after testing was recommended by the using arm or service, coordinated through the appropriate technical committee. This committee submitted recommendation for classification to the Commanding General, ASF, for approval. The classification of an item as standard or substitute standard permitted determination of the basis of issue and procurement planning for production. Specifications were prepared by the technical service and submitted to the Commanding General, ASF, for approval.22

Within this general framework, a considerable variety of detailed procedures was possible. The actual inspiration for a new item of Quartermaster equipment might come from any one of a number of sources—the presentation of a new device by a manufacturer or inventor, the idea of a technician in the Research and Development Branch or in one of the manufacturing depots, a report from an observer or a unit on maneuvers or in a theater of operations calling attention to a deficiency or a need, the examination of a piece of captured enemy equipment, the need for conserving a critical material, or the alteration of a related item. If the project originated in or first came to the attention of the Research and Development Branch and was approved there, normal procedure called for a request to be submitted to Headquarters, ASF,

for permission to develop the item experimentally. If the project first cleared through Headquarters, ASF, and was approved there, the Research and Development Branch would learn of the proposed item by way of a directive to carry on such experimental development. In either case, research to determine the military characteristics of the desired new item was the next step. Technicians of the branch usually secured the collaboration of personnel of the using arms in this work, which involved the study of the functions to be performed by the item, the prospective military and geographic conditions of its use, the review of similar existing equipment, and the functional relationship of the proposed item to other pieces of equipment. Preparation of the design followed, most often with the assistance of one of the Quartermaster manufacturing depots, an industrial firm, or a whole industrial group. An experimental order would then be placed with a manufacturer, or the necessary test samples might be made in a manufacturing depot.

When samples sufficient for testing had been procured, laboratory tests would be undertaken under the direction of the Test Section, These tests might be conducted in the Corps’ own facilities—the manufacturing and testing depots or the Climatic Research Laboratory, for example. They might be made by a cooperating agency, such as a government, university, or industrial laboratory. Field tests followed, coordinated but not directed by the Test Section. These were usually conducted by a number of appropriate service boards, normally including the Quartermaster Board.

On the completion of the test program, the item was presented to the QMCTC for adoption. In this committee, which usually operated through subcommittees, the arms and service which were interested in the item were able through their representatives to make known their views. If the item was approved by the committee, it was forwarded to Headquarters, ASF, for final adoption. A new item might be adopted as “standard,” representing the highest qualifications for the purpose intended and therefore preferred for procurement. Or it might be classified as “substitute standard,” representing something less than the most desirable qualifications but the best immediately available because of material shortage or for some other reason. It could therefore be procured as a substitute for a standard article. With the development of a new item to replace another, the latter might be reclassified as “limited standard,” representing an article which did not have as satisfactory military characteristics as a standard article, but which could be used as a substitute since it was either in use or available for issue to meet supply demands. Upon the adoption of the item, a basis of issue for it was prepared, specifications were written, and a plan for its procurement was drawn up.23

The organizational background was identical for product development in both clothing and equipment24 and consequently has been here presented as a unit, preliminary to discussion of the developmental work in these two fields. Since similar methods of testing were applied to items of clothing and equipment and the same general procedure was utilized to achieve their standardization, these aspects have also been treated at this point as a unit. Against this background the specific achievements in the development of clothing and equipment during the war years, as well as the trends and problems involved in research in the clothing field, are analyzed in the following sections.

The range of Quartermaster product development was wide. Hundreds of new items were developed during the war and many previously

adopted items were modified in the light of criticism from the field. Projects were initiated ranging in variety and complexity from the development of asbestos mittens to the design of command tents. Since only a selective account of this work is possible, primary emphasis has been placed on the development of items of combat clothing and equipment. In combat the enlisted man and the officer wore the same combat clothing whether it was herringbone twill in the Pacific or olive drab woolens in the ETO. New items, commonly used, have been emphasized, although examples have been drawn from among the more specialized items to illustrate the impact of global war upon Quartermaster research.

Winter Combat Clothing

The American soldier went into World War II clad in a uniform evolved from that of World War I. In the wave of economy that swept Congress after 1918 it was deemed unnecessary for the Army to have a dress uniform. As a consequence, the combat uniform of World War I underwent gradual modifications in the interval of peace until it approached as nearly a dress uniform as it could. The basic uniform of World War I consisted of olive drab woolen service breeches and coat. The latter was designed as a single-breasted sack coat with a standing collar. Beginning in 1926 the “choker” collar of the coat gave way to a collar-and-lapel design, necessitating the use of a tie. A black silk four-in-hand cravat was selected. Gradually during the thirties trousers replaced breeches as a standard part of the uniform, but it was not until 1 February 1939 that they were authorized for all arms and services.25

At the beginning of the emergency this service coat and the trousers comprised the basic uniform. It was not really a dress uniform, and, as was promptly disclosed in World War II, neither was it a good combat uniform, although a bi-swing back had been adopted for the coat late in 1939 as a means of providing a more functional garment. To meet its shortcomings a field jacket was designed and developed in the same year to be used in lieu of the service coat in the field.26 Under the pressure of material shortages the silk tie gave way to a black wool worsted tie in 1940 and then to an olive drab mohair tie by the end of 1941. In 1939 canvas leggings had replaced the spiral leggings of the World War I infantryman.27

Global war caught the Army short of clothing specialized for extreme climatic environments, and of necessity much of the early work on clothing was devoted to filling this need. In the development of cold-climate clothing, which was pushed first because of the urgent program of defense measures involving the sending of an enlarged garrison to Alaska, the OQMG utilized the principle of “layering.” More and more, experienced cold-climate men had abandoned the use of furs, using instead loosely woven woolens, covered by windproof garments of light but finely woven cotton, to protect the enclosed air from wind erosion. This layering principle had become widely accepted before the outbreak of World War II, and the OQMG, after utilizing it in the development of arctic combat clothing, also applied it in the development of the standard winter combat uniform of the American soldier.

Service uniforms of 1918 and 1941

In line with this development was the adoption of a plush-type or “pile” material for inner garments. The idea of shifting away from the use of furs as a major reliance in the design of cold-climate clothing was particularly stimulated in 1941 by the upholstery industry, which was in search of new business since the automobile industry, under government compulsion, was cutting down on its production of pleasure cars. Once tests had demonstrated early in 1942 that satisfactory clothing for arctic use could be made of pile, more and more cold-weather garments, such as caps and liners for field jackets and parka overcoats, were made of this material.28

The Army’s initial emphasis on special troop organizations resulted in concentration on the development of specialized clothing to meet the needs of such units. Thus, special cold-climate clothing was designed for the new mountain troops. The Armored Force asked for and received a different winter uniform, snug fitting and with a minimum of protrusions, for wear in tanks. Another special uniform and special jumping boots were developed for parachute troops. For a time it seemed that there was to be no end to the specialty uniforms, each bringing its own new production problems. Their bewildering variety placed a heavy burden upon the system of distribution, and it was inevitable that a reaction should set in. After the first year of the war Quartermaster efforts were centered on the development of combat clothing adaptable to general issue.

Developmental work on the winter combat uniform was initiated early in the fall of 1942 when Col. David H. Cowles, then chief of the Military Planning Division, requested the early development of a combat jacket and trousers. It was proposed to use 9-ounce sateen or a fabric having similar wind- and tear-resistant characteristics for the new battle trousers and jacket in order to provide a satisfactory wind-resistant outer shell. The theory was that these garments, when worn alone, would provide a battle dress for mild weather; when combined with pile fabric liners, they would offer adequate protection for severe weather. It was thought that the combination of wind-resistant, water-repellent, cotton outer shell and pile liner would permit the elimination of the overcoat, the mackinaw, and the olive drab field jacket.29

An experimental combat outfit was soon under test, but developmental work progressed slowly, since differences of opinion arose between the ETO and the OQMG as to what constituted the most desirable combat outfit. The Research and Development Branch supported the use of the layering principle. The new winter combat uniform30 it developed consisted basically of a cotton outer shell with layers of insulation added inside as warmth was needed. The cotton outer shell consisted of olive drab field trousers and a field jacket, M-1943, both made of 9-ounce sateen, for which 9-ounce oxford cloth was later substituted in 1945 as an improved wind-resistant fabric.

In the process of standardizing a basic combat uniform, the object of the Research and Development Branch was to simplify the clothing issued to the enlisted man by eliminating many special types. Thus, the assembly of wool trousers and cotton outer shell which was standardized by the summer of 194331 replaced five other types heretofore issued to the soldiers. Kersey-lined trousers, winter-combat trousers, mountain trousers, wool ski trousers, and parachute-jumper trousers were all declared limited standard. Similarly, five different types of

Utilization of the layering principle. Note combat boots.

Field jacket M-1943. Note buttoned collar (left) and adjustable tie cord (right).

jackets32 previously issued were replaced by the field jacket, M-1943, which was standardized on 12 August 1943.33 This new jacket, developed along windbreaker lines, provided many new functional characteristics lacking in the previous field jacket. Its greatly improved closures at throat, cuff, and waist gave added protection against wind. Its four large cargo pockets provided substantial carrying capacity. Its full-bloused effect afforded freedom of movement, and its design was such that the jacket could be worn satisfactorily by itself or over successive layers of wool underwear, wool shirt, high-neck sweater, and pile jacket. This new combat uniform was tested not only in this country but also at Anzio by the 3rd Division. Subsequently, when publicity on the new uniform was released, it was reported that the new battle dress had “terrific effect on the morale of the men” who wore it on the Fifth Army beachhead in Italy.34 As a result of the 3rd Division’s favorable report, the combat uniform was approved and requisitioned by the North African Theater (NATO).35

While the Research and Development Branch sponsored the layering principle in the new

Combat uniform with hood

combat uniform it was developing, Headquarters, ETO, advocated a uniform similar to the British battle dress. They indorsed a short wool jacket as the outer garment of the combat uniform. As early as 1942 the idea of what later evolved into the wool field jacket was conceived by Maj. Gen. Robert M. Littlejohn, Chief Quartermaster, ETO, under whose direction the design and development of the ETO jacket were perfected by Lt. Col. Robert L. Cohen. A considerable number of such jackets was locally procured, and, after extensive tests had been conducted among the field forces in England during the summer of 1943, specific recommendations were made to the War Department.36 In the fall of 1943 further impetus was given to this project by a letter from General Eisenhower to General Marshall, which in turn was passed on to The Quartermaster General, suggesting that a wool jacket, along the lines of the British battle jacket but with a distinctive style, be considered.

The OQMG had been working on its combat uniform to replace the multiplicity of uniforms then plaguing distribution, and it did not view favorably the development of still another uniform. From the beginning therefore it sought to place the wool field jacket in the layering pattern that it had adopted. It was aware of developments in the ETO, and upon the basis of analysis of the British battle dress, it developed a series of model jackets which, beginning in September 1943, the office sent to the Chief Quartermaster of the ETO. These were eventually modified to produce one model that incorporated all desirable features. A model of the wool field jacket developed by the Research and Development Branch was shown to the Chief Quartermaster, ETO, and his staff on 16 February 1944. They regarded the jacket as inferior to the ETO-style jacket developed in England. Furthermore, they stated that it could not be produced in quantity in the ETO. Since issues had already been made of the ETO-style jacket, the American type, it was argued, would only complicate matters by offering two contrasting styles of the same garment.

The OQMG and the ETO were moving toward agreement on design, but there were deep differences of opinion on the place of the wool jacket in the uniform system. The OQMG, guided by a physiological-climatological approach to the problem, embraced the application of the layering principle. It was convinced that the wool jacket, which could be worn for both combat and dress, should replace the coats of the enlisted man and the officer, at least in theaters of operations.37 From the standpoint of warmth, the garment was regarded as adequate for wear in the temperate zone when combined with the field jacket, M-1943, wool shirt, and wool undergarments. On the other hand, it felt that the proposed ETO uniform without the M-1943 jacket was “sadly lacking in water repellent items” and would not be adequate for the wet-cold weather conditions that prevailed in France.38

The OQMG attempted to keep the theater informed on the new items being developed, but this could only be accomplished by letter, since the office had at first no success in obtaining approval for observers to visit the theater. Early in February 1944, however, Capt. William F. Pounder was sent to the ETO as a field observer to exhibit the new combat uniform

developed by the Research and Development Branch, but the theater was reluctant to have him demonstrate the items to supply officers. The Chief Quartermaster had at first been much interested in the field jacket, M-1943, and its use with the wool field jacket fitted into ETO plans, but only if it could be obtained in sufficient quantities to dress units uniformly. The small amount of depot stocks then available and the low production figures were disappointing.39 Time and availability were the problems.

General Littlejohn made a personal visit to the United States in the spring of 1944 in an effort to expedite the approval of the final design and the initiation of production of the wool field jacket. On 18 April samples of the latest jackets were reviewed by representatives of the Chief Quartermaster, ETO, the ASF, and the Military Planning Division, OQMG. Insofar as developmental questions were concerned, a basic design was agreed upon with certain modifications in detail of design recommended for further investigation. On the other hand, decisions at this conference on availability and the supply of jackets apparently were not definitive and clear and became the crux of the later controversy on winter clothing.40 Jackets embodying the conference modifications were submitted for final approval to Headquarters, ASF, and to the Quartermaster, ETO. The following month Headquarters, ASF, directed that the wool field jacket be presented to QMCTC for classification as to type, but such action was deferred in order to give the using arms and services time to consider their requirements for the garment. Not until 2 November 1944 was the wool field jacket classified as the standard item of issue and the wool serge coat reclassified as limited standard.41

This wool field jacket had been designed primarily as a field garment which could also be used for dress purposes. It was a component part of the combat uniform, but in extremely cold climates the pile liner was substituted for it. The wool field jacket was supposed to be so fitted that it could be worn over the wool undershirt, flannel shirt, and high-neck sweater, and under the field jacket, M-1943. The application of the layering principle, however, broke down in practice because men would not wear the wool field jacket in combat, preferring to save it for dress wear when they were returned to rest areas.

The existing lack of knowledge of the War Department uniform as a complete unit and the limited use made of the M-1943 assembly during the war prevented a thorough combat test of the assembly. It was not used in the ETO, where the wool field jacket was not issued in quantity during hostilities, although experimental quantities were issued to troops in the field. Only in Italy during the winter of 1944-45 was the M-1943 assembly used as planned. Even when the assembly was issued as a unit, troops tended to regard the wool field jacket as a dress item and they did not wear it in combat. The sweater and the field jacket, M-1943, alone were not sufficient to keep the men warm in severe weather. Information obtained at Camp Lee from men returning from the Mediterranean Theater revealed that they obtained the additional warmth made necessary by their refusal to wear the short wool jacket for both combat and dress either by wearing two sweaters or by cutting a blanket to fit and sewing it inside the jacket, M-1943.42

These facts were confirmed by the findings of a representative of the Clothing Section of the Research and Development Branch, who visited the ETO in the summer of 1945. He, too, found that soldiers had a tendency to have the jacket fitted too small for combat use because they thought of it in terms of a dress item. The difficulties in fitting the jacket had developed because it was not understood to be a component part of the field uniform. Conditions were corrected by instructing personnel responsible for the issue of the jacket on its purpose, how it should be worn, and how it should be fitted in conjunction with the various layers of the combat unit to obtain the maximum flexibility and functional benefit from the item.43

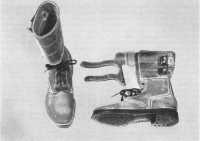

Fundamentally the new combat uniform of 1944 was the same uniform that the OQMG, in conjunction with a board of officers from the AGF, had recommended in March of 1943. In lieu of the pile jacket liner the short wool jacket was substituted, although for extremely cold areas the pile liner was still utilized. As a result of repeated requests from field observers, one new item was added to the outfit in 1944, namely, a hood for the field jacket, M-1943. With the new combat uniform the American soldier wore a newly designed, olive drab, cotton field cap and new combat boots, designed with a wide cuff at the top and made of leather with the flesh side turned out. In cold, wet weather he wore the shoepac.

The final design of the combat uniform was accomplished only after prolonged developmental work by the Research and Development Branch on the individual garments comprising the outfit. Only after the difficult problem of the short wool jacket had been satisfactorily solved, both as to design and its place in the combination of garments composing the combat uniform, did Headquarters, ETO, indorse the latter.

The difference of opinion between the ETO and the OQMG regarding the combat uniform had serious effects on the supply of clothing in the ETO in the winter of 1944-45. The theater had planned to supply clothing and equipment in accordance with Table of Equipment 21, the new comprehensive table for clothing and individual equipment. As changes were made in this table theater plans were changed accordingly. Of the new clothing items scheduled to become available for general issue from production during 1944, the theater included in its plans the wool jacket and the high-neck sweater but not the field jacket, M-1943. The War Department and the OQMG in accordance with the layering principle had recommended that the latter be worn over a combination of other garments to replace the overcoat in the ETO. However, the theater decision, approved by SHAEF, rejected the field jacket, M-1943, in favor of the overcoat for general issue. It was reluctant to accept the field jacket, M-1943, on the supposition that acceptance of it would preclude the adoption of the short wool jacket.

The theater intended the wool field jacket to be the basic garment for all troops. Unfortunately, although a schedule of delivery that would meet its needs was promised, it proved impossible to develop the required production in time. Production was limited by the lack of pocket-creasing machines and by the style of tailoring which required manufacture by the men’s clothing industry. Every effort was made to accelerate production, but shipments lagged appreciably behind the promised schedules.

Until the wool field jacket became available the theater was promised continued shipments of the earlier olive drab field jacket which was limited standard but an authorized substitute for the field jacket, M-1943. This old style jacket, however, was out of production, and supply could only be made from remaining zone of interior stocks which were exhausted before the wool field jacket became available. As a consequence, the ETO then submitted requisitions for the field jacket, M-1943. Because of the theater’s earlier decision not to requisition this jacket, a cut back had been made in the originally planned production which resulted in a short stock position in the zone of interior and an inability to meet requirements when the ETO submitted its requisitions in the fall of 1944. As a result, some soldiers had the wool field jacket without the field jacket, M-1943; others had the later jacket but not the wool field jacket to wear with it. In such cases the men were not properly dressed, and it was necessary to issue the overcoat for combat wear in Europe during the winter of 1944-45, although the overcoat had come to be regarded as a dress rather than a combat item. The differences in point of view and the results stemming from them account in part for the difficulties encountered by the ETO in supplying clothing in the winter of 1944–45.44

Summer Combat Clothing

While winter combat clothing was used during the greater part of the year in the ETO, herringbone twill suits, though originally developed as fatigue clothing,45 became the accepted year-round combat clothing in the tropical Pacific areas. The development of herringbone twill clothing involved a multiplicity of problems, ranging from the use of camouflage patterns and the reversibility of garments through the addition to such clothing of protective features against gas; design and construction details; manufacturing difficulties; and the relative place of the one- and two-piece suits in the clothing program.

These problems culminated in a general review of the entire subject of the battle dress in the fall of 1942. As in the case of winter combat clothing, the initial tendency of the QMC had been toward the development of a wide variety of specialized types of one- and two-piece herringbone twill suits, such as working suits, protective suits, desert suits, and jungle suits. By September 1942, however, it was felt that, except for special forces operating in climatic extremes, it would be desirable to move in the direction of a single design.46

At the suggestion of the Philadelphia Depot the first step in the process of simplification was taken by eliminating special protective clothing to be used in the event of a gas attack. Instead, existing herringbone twill clothing was modified by the addition of protective flaps, such as flies and gussets at the sleeve and front openings of the one- and two-piece suits, which would assist in gas protection. These protective flaps, imposed by the Chemical Warfare Service, were disliked intensely by men serving in the jungles, but they were used on all herringbone twill clothing throughout the war.47

In the fall of 1942 the desirability of using camouflage patterns for all summer combat garments was another problem under consideration. The development of camouflage patterns and all problems relating to color were responsibilities of the Corps of Engineers, which advocated no less than three color combinations. Samples of clothing utilizing different camouflage patterns were shown to the QMCTC in the summer of 1942. It was suggested that clothing could be regular herringbone twill one- and two-piece suits of standard appearance on the exterior but with camouflage patterns printed on the inside. The possibility of reversing the garments would make them useful under varying conditions.

The use of camouflage in different colors and patterns would require several different suits, multiplying the problems of issue and handling. The Corps of Engineers insisted that its studies showed that camouflage clothing should be available to all military personnel abroad. The AGF, however, opposed this view although they agreed to the necessity for outfitting snipers in camouflage suits. These conflicting opinions were resolved by the end of 1942 when a directive from Headquarters, SOS, was received by the OQMG instructing that no further consideration be given to camouflaging regular issue garments. This directive followed action by the Corps of Engineers in October to approve the use of an olive drab No. 7 green shade as the best available all-purpose camouflage color for combat clothing.48

However, a camouflage pattern, in a green combination on one side and tan on the other, was applied to the jungle suit but not with notable success. Reports received from the Southwest Pacific Theater criticized this camouflage jungle suit as too visible when men were in motion. A camouflage pattern was considered satisfactory for snipers, but it was felt that moving troops did not require a special suit. Subsequently, Headquarters, AGF, reported that the special jungle uniform was considered unsuited for use in jungle areas, a fact verified by officers of the United States Marine Corps who had had battle experience in jungles. “The consensus of opinion is that the dark green No. 7 shade is desired because it provides the best blending color for jungle areas.”49 The War Department General Staff directed that, after stocks of camouflage cloth on hand had been utilized, the herringbone twill camouflage jungle suits were to be reclassified as limited standard. This was accomplished by 30 March 1944, and the recommendation of the QMCTC that no further shipments of these items be made to theaters of operations was approved.50

A problem in relation to herringbone twill clothing demanding immediate attention in the fall of 1942 was the necessity of simplifying design in order to obtain sufficient production of the garments. Such action would enable manufacturers of work clothing to handle the large quantities of one- and two-piece herringbone twill suits. It would bring into production of military items a class of industry then contributing little. At the same time it would

release other producers for the manufacture of jungle suits and winter combat outfits.

Such simplification of design was initially accomplished, for example, through the elimination of a decorative pleat in the jacket pocket of the two-piece suit and the substitution of a simple hemmed style for the shirt-type cuff of the sleeve. In February 1943, in view of the heavy procurement of herringbone twill clothing planned for the months ahead, a conference was held at Philadelphia between depot and OQMG representatives to discuss changes in manufacturing operations which would facilitate procurement. The design of herringbone twill clothing was thereupon further simplified, as, for example, by the substitution of a plain, one-piece back for the bi-swing back heretofore used in making the one-piece suit. By simplifying manufacturing operations as well as offering optional specifications, the OQMG hoped to increase production of herringbone twill garments.51

A problem of design that persisted throughout the war years and seemingly defied solution was the incorporation of a drop seat in the design of the one-piece herringbone twill suit. Originally requested by the Desert Warfare Board in the summer of 1942 and subsequently discarded as efforts to produce special clothing for desert troops were abandoned, the request was renewed by the AGF in May 1943.52 At first these requests were in conflict with the efforts being made to promote greater production of herringbone twill clothing by simplifying manufacturing operations. It was the general opinion that a one-piece suit with a drop seat would cause insurmountable difficulties from a procurement standpoint. When renewed efforts at redesigning the garment were made between 1943 and 1945, it was found impossible to develop a satisfactory type of drop seat that would meet the requirements of protection against chemical warfare. Finally in the spring of 1945 the AGF decided to eliminate this requirement from the military characteristics demanded in the design of a one-piece working suit.53

Jungle Combat Clothing

While the general trend in the OQMG was toward the development of one uniform suitable for summer combat wear by all troops, an exception was made for troops operating in the jungle. Although the OQMG had received no official request from any source, it had been at work for some time on the development of jungle equipment when suddenly, toward the end of July 1942, General MacArthur urgently requested 150,000 sets of special jungle equipment including a jungle uniform.54 The AGF formally sanctioned the development of a jungle uniform having certain military characteristics on 28 July 1942. It was to be a one-piece herringbone twill suit with tight-fitting cuffs at wrist and internal adjustable suspenders to take the weight of clothing and equipment from the shoulders and collar of the garment, thus improving ventilation and preventing insect bites through clothing. The suit was to have two large cargo pockets on the sides at the hips and two medium-sized cargo pockets on the waist. The fabric was to be insect-proof and made up in camouflage pattern. The OQMG took swift action. Samples were prepared by the Philadelphia Depot and a specification was drafted.

Within a month the jungle suit had been standardized.55

Even as the one-piece jungle suit was being developed and procured, a second school of thought stressed the advantages of a two-piece jungle suit. Although the one-piece suit had been useful in Panama where it was first tested, in the jungles of New Guinea it proved a failure. Here the “frog-skin” suit was reported as “too heavy, too hot, and too uncomfortable.”56 When wet, herringbone twill increased in weight substantially, adding to the load carried by an individual soldier under humid, tropical conditions. The most serious criticism was the lack of a drop seat in the suit. The fact that men had practically to disrobe to perform normal functions, thereby exposing themselves to the bites of any and all insects, defeated the purpose for which the uniform had been designed, namely, to give the maximum protection against the forays of insects carrying such diseases as malaria, dengue fever, and scrub typhus. On the basis of the arguments advanced, the advocates of the two-piece uniform were successful in substituting that outfit for the one-piece jungle suit in the spring of 1943.57

The two-piece jungle suits proved more popular than the one-piece suits, but the OQMG felt that there was room for improvement. Criticism of the issue of herringbone twill garments for jungle use continued. Inasmuch as little clothing or textile design of a radical nature had been evolved to provide the necessary protection against insects, terrain, and other environmental hazards encountered in jungle warfare, the Military Planning Division initiated a comprehensive project in requirements for jungle clothing in August 1943. This included field study at the Everglades in Florida, tests for physiological reactions in hot, humid atmosphere conducted at Indiana University and wear tests at Camp Lee.

The Textile Section sought to perfect a jungle cloth which would be thin, dense, and of the lowest possible water-holding capacity. Poplin and Byrd cloth were found to be cooler, to weigh less when dry, to absorb less weight of water, and therefore to dry more quickly than any of the other fabrics tested. As tightly woven fabrics, they also gave better protection against mosquito bites. The Committee on Jungle Clothing recommended the adoption of poplin.58

At the same time the Clothing Section of the Research and Development Branch worked to perfect the most desirable design for a jungle uniform. Many modified styles of the basic two-piece suit were developed in experimental models. Jungle combat uniforms made in the new design and from the new fabrics were tested during the period from 1 July to 1 November 1944 at Bougainville, and by the 41st Infantry Division during September and October 1944 on Biak Island. In addition, they were tested in the Central Pacific Area and the China-Burma-India Theater. During the summer of 1944 the Quartermaster Board also undertook a comprehensive field test of tropical clothing, equipment, and rations at Camp Indian Bay, Fla.59

A lightweight tropical combat uniform had been desired by all the theaters in which it was tried experimentally. The War Department General Staff had also expressed a desire for this

uniform. Action to initiate its manufacture, however, was delayed because of the shortage of fabrics at that time. Not until June 1945 did the OQMG near its production goals. Only then was it possible to divert 5-ounce poplin to the manufacture of jungle uniforms. So great had been the demand for lightweight, wind-resistant fabrics that a choice had had to be made between the manufacture of winter combat uniforms to protect men from the cold and rain and lightweight jungle uniforms to ease the burden of the heat. On 11 July 1945 standardization of the new jungle uniform was approved by Headquarters, ASF,60 but the war ended before the new uniform could be issued to troops in the field.

Combat Headgear

One of the important contributions to the comfort and safety of the soldier was the development of the helmet assembly.61 In World War I the American doughboy had worn the M-1917 helmet which was neither comfortable nor an adequate protection from shrapnel flung upward from the ground. The steel helmet and liner of World War II was a radical departure from the “tin hat” of the first war. Consisting of an outer, pot-shaped, steel body and a snugly inserted plastic shell which contained a suspension to fit the whole assembly comfortably to the wearer’s head, the helmet and liner were always worn in combat, except in the jungle where the liner alone was sometimes used for combat fighting.

In the forward areas of all theaters the liner was commonly worn in place of the garrison cap. It was suitable for wear both in the tropics and, with the addition of a specially designed knit cap, in the Arctic. Since the steel helmet itself was without head harness, it could be used as a wash basin or bucket and in many other ways. Made in one size to fit the conformity of the steel helmet, the liner carried an adjustable headband inside the suspension which, with a neckband (issued in three sizes), made possible a close fit to the head. Together, helmet and liner weighed approximately 3 pounds, and the liner alone weighed about 10 ounces.

While the Ordnance Department was responsible for the development of the combat helmet, the liner for it was developed as a joint product of private industry, the Ordnance Department, and the QMC. The helmet and liner idea had been originally suggested as early as 1932. The first tangible version, however, was derived in large part from a plastic football helmet and suspension invented and patented by John T Riddell, a Chicago manufacturer of football supplies. The Infantry Board in early 1941 was the first to consider the design of the Riddell football helmet likely for adaptation in developing a substitute for the cumbersome and unsafe steel helmet of World War I. The Ordnance Department then took a hand in the development of sample liners, utilizing the football helmet suspension, but before the year was over the QMC had contributed a great deal of experimentation, and the liner, originally developed as a fiber hat worn under a steel shell, had been made a Quartermaster item.

Almost from the first, however, the fiber liner was considered unsatisfactory. From the summer of 1941 the Standardization Branch of the OQMG conducted experiments on liners, using various plastics, and enlisting the cooperation of several industrial firms. In 1942 a plastic shell was substituted for the original fiber liner, and proved to be a stronger, longer-wearing item.

The first plastic liners were unsatisfactory in many ways, and the Research and Development Branch, successor to the Standardization Branch, sought to improve them. The helmet liner was anything but static in design after the first experimental stages had passed. Industry and the Research and Development Branch in cooperation with the Chicago Quartermaster Depot, the procuring agency for the item, worked long and hard to examine and perfect any suggested changes that would make the liner a more comfortable headpiece. The adjustable headband, which eliminated burdensome tariff sizes, was worked out; hardware was redesigned so as to be as comfortable as possible and eliminate many pressure points on the wearer’s head; a chin strap which could be removed for the delousing operation was developed; and a textured paint coating, less inclined to chip and less reflective, was also developed.

The proposed use of the helmet assembly had led the OQMG in 1941 to undertake a comprehensive survey of all headgear for purposes of simplification. When the helmet assembly was adopted, it was necessary to develop a woolen liner to provide warmth in winter. The Chief of Infantry advocated the use of a skullcap, but the QMC, because of manufacturing difficulties limiting production, favored a knitted cap, which was adopted as a standard item of issue on 26 February 1942.62

The Chief of Infantry remained unfavorably disposed toward the use of the knitted cap, and in October 1942 a project was initiated to develop an all-purpose field cap. Using a ski cap as the point of departure, the OQMG continued developmental work until there was devised early in 1943 a windproof, water-repellent poplin cap with a stiffened sun visor, which gave protection to the eyes without protruding beyond the helmet liner. This field cap, M-1943, was designed to be worn with the field jacket, M-1943. It could also be worn under the hood of that jacket and with the steel helmet and liner. At the same time a pile cap of improved military characteristics was designed for wear in extreme cold. The Research and Development Branch decided that these two items of headgear met all the requirements for temperate, cold, and arctic climates, and they were subsequently classified as standard, thereby eliminating a multiplicity of field caps previously used.63

Combat Footgear

Adequate footwear is essential in war, for it may determine in no small measure the outcome of a battle. The fact that World War II was fought in many climates and terrains complicated the QMC’s problem of supplying adequate footwear. That problem was also made more difficult as a result of the fortunes of war which cut off many sources of raw materials.

The trend of development in both world wars was similar. The Army was caught unprepared for the emergency in both instances. In World War I the first issue of footwear was the peacetime shoe recommended for adoption by the Munson Board in 1912. A sturdier marching shoe appeared by May 1917, but it was not until the spring of 1918 that a heavier shoe with more waterproof construction was developed to suit the demands of trench warfare. The so-called “Pershing” boot, made of leather with flesh side out and a hobnailed sole, was admirably designed to meet the demands of combat service for that period.64

As in the case of the World War I combat uniform, so the combat shoe underwent modification after the war to emerge as a more suit-

able garrison shoe. it was developed for a small peacetime army with a regard for appearance and comfort. Made with grain side out, polished upper leather, full leather outsoles and whole leather heels, this Type I service shoe was obviously a product of an economy of surplus. Some official studies of combat-type footgear were conducted during the twenty years following World War I, but the specification for service shoes remained substantially unchanged at the beginning of the period of emergency in 1939. Until September 1941 all service shoes procured were Type I.

Instead of profiting by the lessons of World War I, the QMC entered World War II pursuing the same course of action with regard to shoes that it had taken in 1917. Starting with a peacetime shoe, it developed one of greater durability until finally a shoe of the type of the Pershing boot was again specified. Apparently no thought was given to making use of this specification to begin with, although it had proved very satisfactory during the closing months of World War I.

As the emergency period began, although the need for a sturdy combat shoe was obvious, Quartermaster personnel showed a lack of imagination in anticipating requirements. Thinking was still in terms of a peacetime army. The major question of discussion during 1939 was the possible replacement of the high-top garrison shoe with a low quarter shoe in the interest of appearance, comfort, economy, and morale.65 With the federalization of the National Guard and the establishment of the Selective Service System in the fall of 1940, the military program began to assume wartime proportions. The year before our entry into the war was marked by considerable developmental work.

During the small-scale maneuvers characteristic of the early training period, the light service shoe, Type I, issued to the soldiers worked out satisfactorily, but complaints were numerous that the outsole wore through in the short period of two to three weeks. Government technicians, in an effort to develop more durable soles, turned their attention to the use of composition soles. Experiments resulted in a revised service shoe, Type II, which utilized a rubber tap and heel.66 But just as the Army succeeded in producing a sole that would wear, it was forced, because of the serious rubber shortage, to keep reducing the new rubber content of these taps until the point was reached when no new rubber was used and taps were made entirely of reclaimed rubber.

As materials shortages increased, the motivating factor behind all initial wartime developmental activities in the field of footgear became conservation of resources. During 1942 there was a considerable amount of experimental work toward such conservation, although the Boston Depot insisted that standards of current specifications ought to be maintained. Lighter insoles, strip gemming, cork filler material, reclaimed rubber taps, wood-core heels, and zinc-coated steel reinforcing nails were introduced into the manufacture of service shoes to conserve leather, duck, rubber, and brass. The service shoe was actually being weakened when the sturdiest possible footgear was needed.

About mid-1942 the Research and Development Branch, OQMG, became interested in a boot which would supplant the shoe and legging combination in use since the beginning of the war but thoroughly disliked by the troops. Laces broke, leggings wore out quickly and were difficult to put on and take off. Observers’ reports subsequently indicated that rather than go

through the tedious procedure of removing their shoes, soldiers occasionally went for long periods without taking them off, thus opening the way to foot ailments.67

Since the combat boot eventually produced was a product of complicated developments, it is difficult to trace any particular shoe as its predecessor. Initially the Desert Training Center had stimulated interest in a combat boot by its request for a special boot suitable for desert troops. The scope of the project was widened to develop a combat boot suitable for all troops. A thorough examination of all the service shoes in use at the time revealed that the type of construction sought was most closely approximated in the Canadian combat boot, a heavy-duty shoe with a cuff and strap at the top. The OQMG requested the Boston Depot to produce samples of boots of this type.

Development of the combat boot was stimulated by the findings of the Chief of Staff, General Marshall, after his return early in 1943 from an inspection tour of the combat zone in North Africa. He reported in conference on 1 February 1943 that the service shoes were unfit for field use and that he would request the development of a “suitable shoe along the lines of the field shoe issued in France during the last war.” The shoe in use in the combat zone was “too light, and too much on the order of the garrison shoe for field service.”68

Samples of improved shoes had been developed earlier by the OQMG, and these were submitted to the Chief of Staff on 5 February. A decision was reached to change production as soon as possible from the Type II service shoe to a new Type III shoe. The latter was to be made with flesh-out upper leather and a full rubber sole and heel, which, with the scarcity of rubber, was later changed to reclaimed and then to synthetic rubber. The use of flesh-out Army retan had been decided upon because it was more durable, it absorbed dubbing more readily, thereby increasing the qualities of flexibility and waterproofing, and it was more comfortable in the breaking-in stage than grain-our leather.

At the same time it was also decided to produce a new combat boot in limited quantities for test purposes. The boot was the same as the shoe, plus a cuff and buckle top which gave it a 10-inch height as compared to the 6 inches for the Type III shoe. The boot was intended to eliminate the shoe and legging combination worn by infantrymen and the special boot worn by parachute troops.

Deliveries of the Type III shoe began April 1943. By July, experimentation on the combat boot as a replacement for Type III shoes was fairly well advanced. Field test reports were favorable and on 16 November 1943 the QMCTC approved a committee report calling for standardization of the combat boot. A few days later this recommendation was concurred in by the ASF.69 By January 1944 the shoe industry began production of the combat boot for regular issue.

Although the combat boot was well received in most theaters, there was some complaint about it in the ETO in the winter of 1944-45. In the fall of 1944 combat troops in that theater were confronted with mud, slush, and cold—elements against which the new service shoes offered only relative protection—and trench foot appeared.

Trench foot had first showed itself as a serious problem in the summer of 1943 during the attack on Attu, in the Aleutians. Of the total 2,900 casualties during the Attu operation, 1,200 were due to exposure, resulting chiefly in