Chapter 2: Problems in Hawaii, Australia, and New Zealand

In an industrial age an army operating far from its homeland is benefited greatly if it can tap the material resources of thickly populated and economically well-developed countries. It can then utilize already existing docks, warehouses, offices, and even residences and employ thousands of civilians in rear areas as clerks, stevedores, and warehouse workers. Above all, it can procure a substantial part of its supplies and equipment from nearby industrial sources. Through the use of all these material and human resources an army can free its troops from building and supply tasks and make its own manpower more fully available for combat activities. But the vast Pacific contained few populous and industrialized areas. At the outset it indeed contained only three areas—Hawaii, Australia, and New Zealand—that could serve as great supply bases for defensive and offensive operations. While these areas could furnish much food, their industrial development was too rudimentary to permit extensive local procurement of manufactured articles. Nevertheless they constituted indispensable assets to the forces arrayed against Japan.

Hawaii, Mid-Pacific Supply Base

Of the three areas Hawaii since the turn of the century had been the major U.S. out post in the central Pacific. With only about 420,000 inhabitants, few industries, and a highly specialized agricultural system, it was the least serviceable of the areas as a source of supply. But it was advantageously located for use as a base for offensive operations and as a distribution center for forward areas, and this was the role prewar strategists had assigned to the archipelago in case of a war with Japan. On the eve of the attack on Pearl Harbor, U.S. Army activities in the islands were still conducted generally in peacetime fashion. Consequently, troop strength and supply and service resources were far from sufficient to meet the requirements of a major wartime base for operations utilizing hundreds of thousands of men.1

To help the QMC in Hawaii in its task of supporting possible combat activities, plans had been formulated in 1940 and 1941 for the enlargement of its two main operating centers—the Hawaiian Quartermaster Depot, located at Fort Armstrong near the

entrance of Honolulu Harbor, and the Quartermaster warehouses at Schofield Barracks, the Army’s largest garrison post, 20 miles northwest of Honolulu.2 But lack of funds and higher priorities given to building activities more directly related to combat operations prevented the execution of these plans, and no substantial additions had been made to Quartermaster installations by the time hostilities began. Even the construction of underground storage tanks for gasoline was delayed until the War Department after considerable delay approved the project.

On 7 December 1941 Quartermaster covered storage space totaled only 200,000 square feet and open storage space only 8,000 square feet, mere fractions of the square footage needed in the coming Pacific war. Modern mechanical aids in quick handling of supplies—fork-lift trucks, conveyors, stackers, pallets, and cranes—were completely lacking.3 Since peacetime requisitions had been submitted to the San Francisco General Depot sixty days before anticipated need and had been promptly filled, military stocks of food, clothing, and other Quartermaster supplies were large enough to meet the immediate needs of the 42,000 soldiers then in the islands. But they were much too small to support the vastly increased number that was soon to be stationed there or even to make possible a protracted resistance if the enemy should blockade or invade the archipelago.4

In the early months of 1942, when a large part of the U.S. Pacific Fleet lay sunk or disabled in Pearl Harbor, a Japanese attack in force on Hawaii was considered altogether likely. A cardinal objective of the Army was to make the islands a mighty bastion capable of withstanding a powerful attack. With the disastrous naval losses sustained by the foe in the decisive Battle of Midway early in June 1942 making a Japanese assault improbable, the Army’s objective in the following year became the speedy transformation of the archipelago into a vast training, rehabilitation, and supply area. The year and a half following Pearl Harbor was, then, a period of intensive preparations, defensive at first but offensive later, for the QMC as well as for other Army components.

At the outset the basic peacetime organization of the Office of the Department Quartermaster (ODQM) remained substantially unaltered. The Hawaiian Department Quartermaster, Col. William R. White, continued to exercise personal supervision over the formulation of long-range plans and the establishment of policy, the Supply Division to handle day-by-day routine matters, and the Hawaiian Quartermaster Depot to serve as the main operating agency of the ODQM. As in peacetime, post quartermasters consolidated the requisitions of units on their reservations and transmitted them to the Hawaiian Depot to be filled from its stocks. If requisitioned items were unavailable at the depot, it, in turn, sent requisitions for them to the San Francisco Port of Embarkation.5

Distribution Problems

On 7 December 1941 the requisitioning basis was a 60-day supply for 42,000 men. In the following months this basis steadily rose and by July became a 90-day

supply for 139,000 men. Comparable increases in other overseas areas forced the War Department late in January 1942 to promulgate a modified system of supply for all theaters of operations. Food, gasoline, and oil would be shipped automatically without requisition by the ports of embarkation; clothing, equipage, and general supplies would, as in the past, be shipped only on requisition, but the requisitioning agency was now to recommend shipping priorities. During the greater part of 1942 the automatic supply of food, gasoline, and oil worked rather satisfactorily in the Hawaiian Department although shortages developed in some items and excesses in others.6

The sharp rise in the number of troops in the islands and the prospect of continuing increases for the next two or three years required the abandonment of manual methods of warehousing at the Hawaiian Depot, the procurement of the latest materials-handling equipment, and the acquisition of additional storage space. Since materials-handling equipment was scarce in the United States, it was well into 1943 before depot requisitions could be filled. Meanwhile additional storage space was obtained by leasing commercial warehouses in the Honolulu area and, as first-priority defense installations were completed, by erection of temporary structures. These structures were about 100 feet wide and up to 550 feet long, considerably smaller than those in the zone of interior, that is, the United States, where standard warehouses averaged about 180 feet in width and from 1,000 to 1,200 feet in length. Months elapsed before all the needed space was procured, and in the meantime open storage was employed for a good deal of the incoming flood of supplies. Despite the hazards to food and textiles from drenching rains, even the docks and paved streets of Honolulu were of necessity occasionally utilized as storage areas.7 By the end of June 1943 covered storage space at the Hawaiian Depot had risen from 200,000 to 500,000 square feet, or 150 percent, and open storage space from 8,000 to 395,000 square feet, or 4,800 percent. Total space for all supplies except fresh food had leaped from 208,000 to 895,000 square feet, or 330 percent. Extensive though this increase was, it still did not equal the demand, for the QMC was then stocking a 105-day supply for 204,000 men, or an 8.5-fold increase over that on 7 December 1941.

Storage at the Hawaiian Depot never became as efficient an operation as it did on the mainland. Not only were warehouses proportionately fewer in number; they were also widely scattered—partly because leased buildings were dispersed throughout the Honolulu area rather than concentrated in one place and partly because the danger of losing all supply of the same kind by bombing required storage of the same item in many different locations. This decentralization of depot stocks inevitably caused longer hauls and more crosshauls. Though the relative closeness of Oahu to the mainland enabled the depot to obtain more materials-handling equipment than did installations at a greater distance, mechanical aids even here were never as numerous as in the zone of interior. But in spite of its deficiencies the installation probably had better equipment and warehouses than did

comparable Quartermaster establishments elsewhere in the Pacific.8

The Hawaiian Depot at first sent items requisitioned by field units to a few posts that distributed them to the proper units. Since these posts were concentrated about Honolulu, there was danger that a large part of the supplies directly earmarked for field organizations might be destroyed in air raids. Further complicating the distribution problem was the necessity of supplying troops at many small and scattered defensive works hastily built at a considerable distance from distributing agencies. Obviously, war conditions demanded greater dispersion of field stocks.9 A zonal system of distribution was the answer to this problem. Ten Quartermaster supply areas were established on Oahu, and within these areas centrally located supply points, each with its own zone of distribution, were set up. These points consolidated and submitted to the Hawaiian Depot requisitions of units within their boundaries and received and distributed the requisitioned supplies. The larger points served also as subdepots, which maintained reserve stocks of specifically assigned items indispensable to field troops. In Area 9, for example, Schofield Barracks specialized in the reserve stockage of food, and Camp Malakole in that of clothing and general supplies. Points serving as subdepots for food stocks kept a 30-day store of nonperishable subsistence; those stocking clothing and general supplies kept a 90-day store. There were also emergency distribution points. They differed from regular supply points in that they stocked reserves that could be issued only if the normal distribution system broke down, Such reserves usually consisted of a 5-day supply of combat rations and a 5-day supply of gasoline.10

As troop strength outside Oahu rose in the late spring and early summer of 1942, the Hilo, Kauai, and Maui Depots were established. They served, respectively, the Hawaii, Kauai, and Maui Districts, which consisted mainly of the islands bearing these names.11 The new installations furnished supplies within the limitations imposed by sharply curtailed interisland transportation service. Some ships had been withdrawn from this service because of possible hostile attacks, and the remaining ships sailed only at irregular and unannounced dates. Lack of a fixed schedule caused an uneven flow of military supplies into the outlying islands, and the shortage of refrigerated vessels, or “reefers,” made the supply of fresh food a particularly hard task so that rations were monotonous. Eventually, more frequent sailings, made possible by the lessening of serious danger from the Japanese, alleviated this problem.12

The Food Problem

Since Hawaii was no more self-sustaining than England, the maintenance of an ample and varied food supply for both the military and the civilian population was the

most important matter handled by the ODQM during the first six months of the war. For decades the Territory had pursued a specialized tropical economy that restricted agricultural production almost entirely to sugar and pineapples, the commodities with highest cash returns. Temperate-zone products, the chief elements in the diet of the European and American segment of population; rice, the staple food of the Orientals; and feeds and forage for poultry and livestock—these were all grown in small quantities that failed by a wide margin to meet Hawaiian needs.

The islands, as a whole, imported more than half their fresh fruits and vegetables, poultry, feeds, and cereals, a quarter of their meat, and a third of their dairy products. More than 90 percent of the rice, white potatoes, and canned vegetables, and 100 percent of the flour consumed in the islands came from the United States and other outside sources. Oahu, location of 60 percent of the Hawaiian population, heart of the powerful system of naval and military bases maintained by the United States, and the prime target of any foe attacking the islands, produced only about 20 percent of its food and depended more on imports than did the other islands.13 Sugar and pineapples were the only commodities the peacetime Army obtained wholly from local production. Hawaii also furnished fairly large quantities of coffee and fish and small quantities of fresh fruits and vegetables, milk, and meat. But the total value of imports from the United States was usually about six times that of food obtained from Hawaii.14

The development of diversified agriculture was handicapped in many ways. Since the turn of the century production of temperate-zone fruits and vegetables had been declining. Farmers were unable to make a profit commensurate with the time and labor expended, for cultivation of these commodities required costly fertilizers and yielded smaller harvests than on the mainland. As large-scale, industrialized farming became more prevalent on the U.S. West Coast, Hawaiian producers were less and less able to compete successfully. The average grower of fruits and vegetables, usually Japanese, owned only about four acres and had an annual income of only about $500. Unable to afford machinery, he was forced to use uneconomic hand methods. He was further hampered by the fact that the lands most suited to vegetables had passed into the possession of the large sugar and pineapple plantations, so that he was confined in the main to poor soil in regions of excessive rainfall, where his crops were highly susceptible to insect infestation, plant diseases, and vagaries of the weather.15

The lopsided nature of Hawaiian agriculture was a condition that the Army could not ignore, for it meant that the entire population, military and civilian, might be starved by a complete or even partial blockade. Though the armed forces under these circumstances for a time might be fed satisfactorily from their reserves, they could not maintain a protracted defense with a starving people at their backs. Humanitarianism, if nothing else, would oblige them to share their stocks with the 420,000 civilians.

Commanding generals of the Hawaiian Department had therefore increasingly stressed the development of an emergency food program for application in a military crisis involving Hawaii.

When the Department Service Command Section was established at Headquarters, Hawaiian Department (HHD), in August 1935, with the responsibility of planning for civil mobilization in time of war, it was especially charged with the study of the food problem in the islands as a whole and on Oahu in particular.16 The Service Command collected facts pertinent to the production, conservation, and storage of food and conducted experiments showing that sweet potatoes, string beans, lima beans, Chinese cabbage, and peanuts could be grown satisfactorily. It determined that in a war crisis 25,000 acres constituted the minimum amount of land needed to make Oahu self-sufficient in food.17 Even the availability of this acreage for cultivation, it warned, would not insure an adequate supply of provisions, for the islands ordinarily had on hand only small food stocks and several months would elapse before the emergency crops matured. This phase of the problem, the Service Command concluded, could best be handled by the creation of a large subsistence reserve. But this solution required more storage space than was possessed by either the armed forces or the civilian economy. Cold-storage warehouses were particularly scarce, for the peacetime practice of sending perishable commodities direct from incoming ships to retail shops largely eliminated the need for such structures. Even the Army had no space of its own, relying almost wholly on the limited amount available commercially.18

As relations with Japan deteriorated in 1940 and 1941, the Service Command focused increasing attention on acquiring land and storage space in the event of war. Since land and the labor to till it would have to come from the domain of King Cane and Queen Pineapple, the Service Command encouraged planters to develop emergency programs based on its conception of future needs. Late in 1940 the Hawaiian Sugar Planters’ Association, which often exercised a decisive voice in Territorial affairs, started intensive work on such a program. It enlisted the cooperation of the pineapple growers as well as the Army and in October 1941 completed a plan that provided for the restriction of emergency crops in Oahu to four specified plantations, which, since the coastal areas might well be in a combat zone, were all located in the middle of the island. The plan also indicated the tentative acreage and the crops allotted to each plantation.19

To speed creation of food reserves was another matter of immediate interest to the Service Command. Speaking at an Army Day celebration on 6 April 1941, Lt. Gen. Walter C. Short, Commanding General, Hawaiian Department, warned the Hawaiian people of the dangerous status of their food supply and recommended that women buy canned products for storage in their pantries. The press publicized this suggestion, the public responded, and retail sales of food rose about 20 percent during the following month. Notwithstanding that buying subsequently declined, the possible necessity of large-scale home storage had

been firmly implanted in the public mind.20

General Short gave strong support to the Territorial Committee on Food Storage, which was trying to create a central reserve for the civilian population.21 In the spring of 1941 this committee asked the Office for Emergency Management in Washington to buy two million dollars’ worth of rice, flour, canned milk, fats, and oil, the essential commodities imported in the largest volume, but its request was rejected because there were not enough warehouses in Oahu to store such sizable purchases. In September the Bureau of the Budget disapproved a proposed federal appropriation that provided for the construction or lease of warehouses and the stocking of feed for poultry and livestock and of food for human beings.22 Efforts to secure funds for the purchase and storage of seeds likewise failed. Despite the fact the U.S. Senate in May 1940 passed a bill providing for such purchases and for the construction of warehouses to store them, Congress never took any further action.23

During 1941 the Hawaiian Department utilized its procuring authority to give “infant industry protection” to the cultivation of potatoes. Hawaiian potatoes cost almost 40 percent more than the mainland variety but on General Short’s request The Quartermaster General approved their purchase. Short justified the payment of the higher price as a defense measure that would help make Hawaii self-sufficient. Even this price, he claimed, barely enabled the sugar planters, who raised most of the potatoes, to avoid monetary loss.24

The Office of Food Control

Despite extensive planning, civilian food reserves on the day of Pearl Harbor were little larger than if there had been no plans at all. Limited production of a few vegetables had been stimulated, and some subsistence had been stored in housewives’ pantries. But on Oahu an island-wide inventory on 9 December showed only a meager 37-day food supply for the 255,000 civilians. Stocks of rice and potatoes would last for only fifteen days. There were, it is true, approximately 113,000 cattle, equivalent to a 152-day supply, but wholesale slaughter was undesirable because it would leave the island without means of replenishing the herds.25 The expansion of civilian reserves was complicated by the priority given the accumulation of a 70-day supply for 150,000 soldiers and by the withdrawal of the largest freighters from the Hawaiian run to supply the forces in Australia and the South Pacific.26 Since civilian food would be scarce for at least some months, General Short, as Military Governor of the Territory, a position that he assumed on the proclamation of martial law on 7 December, created the Office of Food Control (OFC) to supervise the production, storage, price, and distribution of foods, feeds, forage, and seeds. Only naval stocks were exempt from OFC supervision.27

Just before he was relieved from the command of the Hawaiian Department in mid-December, Short also appointed an

Administrator of Crop Production, who named four coordinators, one for each of the main islands—Oahu, Hawaii, Kauai, and Maui.28 These appointments were all made with a view to the possible implementation of the plan for emergency vegetable production. When Lt. Gen. Delos C. Emmons succeeded Short, he decided that sugar and pineapple land would not be used for the cultivation of vegetables. He based his decision mainly upon faith in the continued even if limited availability of shipping and upon the build-up, already under way, of civilian reserves. He was influenced, too, by the possibility of converting sugar into motor fuel in Hawaii in case of need.29

The burden of insuring an adequate food supply for civilians thus fell upon the newly established OFC. During December and January Colonel White acted as chief technical adviser to this office. In addition he was charged specifically with the determination of civilian requirements and the preparation of a civilian rationing program.30 Though under martial law the OFC had unlimited authority over the distribution of food, it at first used this power sparingly. But it was deeply interested in the creation of an ample reserve. A few days after Pearl Harbor President Roosevelt allocated $10,000,000 from his emergency funds for such a reserve, and late in the month Congress approved the establishment of a $35,000,000 revolving fund. The reserve was to consist of a six-month supply of nonperishables and a thirty-day supply of perishables. The Federal Surplus Commodities Corporation (FSCC) acted as buying agent and, by mid-December, had already begun to assemble stocks for movement to Hawaii. The OFC advised the FSCC concerning shipping priorities and arranged for storage of the reserve.31

On 26 January 1942 Colonel White became Director of OFC with full responsibility for the procurement and distribution of both Army and civilian subsistence stocks. Up to this time the OFC had set up neither a rationing nor a price control system. But the steadily growing cost of food confronted White with a thorny problem that could no longer be ignored. Prices had begun to rise with the buying panic of 9 December and in Honolulu by late January had increased by 10 to 40 percent. Rice was one of several staples that showed disturbingly large advances. Early efforts to check profiteering had stipulated simply that retailers publicly display lists of their prices. The day after White became Director, OFC termed this system a failure and fixed top retail charges for rice, potatoes, fish, and cheese sold on Oahu. Shortly afterwards it began to publish in the Honolulu newspapers notices of permissible prices for a steadily lengthening list of foods. As OFC had no police staff, enforcement of the published charges hinged almost entirely upon the voluntary cooperation of merchants and the willingness of buyers to report violations.32

Meanwhile inflationary forces were daily becoming more powerful on Oahu. As reefers departed from the West Coast of the United States only at irregular intervals, perishable commodities were alternately

plentiful and scarce. To eliminate these oscillations, Colonel White set up shipping priorities, but shortages and surpluses continued to prevail. Actually, Oahu suffered less from such fluctuations than did the outlying islands that relied on very infrequent sailings from Honolulu for the bulk of their fresh food. Apart from the recurrent shortages of fruit and vegetables, forces pushing prices upward were strongest on Oahu. Labor had been scarce in the Honolulu area, and the influx of highly paid workers that started a year before Pearl Harbor was now accelerated by the vastly expanded Army and Navy building program. Moreover, since wages were not frozen, they rose constantly as the armed forces used every feasible incentive to obtain more and more workers from the other islands and from the mainland. The bulging bankrolls of these workers plus those of the tens of thousands of soldiers and sailors swarming into the island exerted a powerful inflationary pressure that made impossible the strict enforcement of maximum retail prices.33

By mid-February some retailers were already asking more than permitted maxima. In justification of their action they pointed out that, though they were forbidden to ask more than ceiling prices, wholesalers were not regulated at all and increased their charges at will regardless of the effect on retail costs.34 To curb continued profiteering, the OFC promulgated a new regulation on 21 February that for the first time put teeth into its orders by making violators liable to suspension or revocation of their licenses, a $1,000 fine or one year in prison.35 In mid-March, the soaring prices of fresh fruits and vegetables, currently in short supply, caused Colonel White to establish wholesale as well as retail ceilings for many perishable commodities. To some extent at least he thus met retailers’ demands for the control of wholesale charges.36

Price regulation alone, no matter how fair, was a mere expedient. The best method of dealing with the recurrent scarcities was to increase the supply. Of this fact Colonel White was well aware. Insofar as the problem resulted from the shortage of reefers, he could do little except point out the deficiency. But insofar as it sprang from restricted cold-storage space on Oahu, he could take action since he was Coordinator of Cold Storage as well as Director of Food Control.37 As coordinator, he took over commercial ice plants and refrigerated warehouses and administered them, along with Army space, as a unit. He regulated the importation of perishables in line with the availability of refrigerated space, and classified and stored fresh foods according to priorities that gave the highest ratings to meat and other products that spoil easily, and the lowest rating to potatoes, onions, and other commodities less subject to rapid deterioration. In order to end nonessential use of space, he stopped completely the storage of beer, syrup, and dried fish and forbade all speculative and long-term storage. Since the enforcement of these regulations freed more and more space for essential items, importation of fresh food was increased.38

While perishable commodities became available in increasing quantities, the civilian supply fluctuated considerably and never quite equaled the prewar average. This development was attributable to

several factors. One, as already pointed out, was the absence of a large cold-storage building program. Another was the higher priority given to the stockage and withdrawal of Army supplies. A third, and the most important of all, was the steady growth of military cold-storage requirements as the number of troops in the archipelago and other mid-Pacific islands multiplied. The shortage of perishables in Hawaii would have been alleviated had it been possible to increase interisland shipping and make public announcement of anticipated arrivals at and departures from the ports of outlying islands that at certain seasons had a surplus of some meats and vegetables. But the prior claims of other Pacific areas and the shortage of reefers made the allocation of enough vessels impossible, and sailing schedules could not be publicized because this information might be conveyed to the enemy.39 Because adequate cold-storage resources were lacking on the islands, the limited number of ships meant that substantial quantities of exportable surplus spoiled; the unavailability of sailing schedules meant that insufficient time was afforded farmers to prepare commodities for shipment after a Honolulu-bound vessel was known to be in port.40

Despite sporadic shortages of meat, butter, and fresh fruits and vegetables, Hawaii did not suffer from lack of food, for nonperishable provisions were always supplied in ample quantities. By mid-February 1942, in fact, a six-month supply of many commodities was already on hand.41 Reserves continued to grow, and by the end of the year danger of a grave scarcity had passed. As the stock of a food item approached or exceeded a six-month supply, part of it was distributed through wholesalers and replaced by purchases from the mainland. A six-month supply was thus constantly in storage.42

After fear of a critical food shortage began to wane in the spring of 1942, the OFC became more and more an agency whose main function was price regulation, a responsibility that involved the enforcement, by military officers, of military regulations applicable to civilians. General Emmons felt that such authority was contrary to democratic concepts of the proper relationship between the Army and the civil population. It should, he thought, be reduced to a minimum, particularly since the Territorial press and Hawaiian merchants were already asking for less military control. Quite apart from these considerations, the Governor believed that sound administration demanded that officers devote their attention to military rather than civil affairs. Aware that more rather than less price regulation was probably inescapable under existing conditions, the Governor nonetheless hoped that it could be carried out under civilian supervision.43

His first step toward achieving this objective was taken in late May, when, at his request, the Office of Price Administration (OPA) sent several representatives from the United States to set up an essentially civilian Price Control Section in the Office of the Military Governor. For the time being, however, the regulation of food prices remained a function of the OFC.44 In October this responsibility was shifted to the

Price Control Section. When this action was followed in March 1943 by the transfer of control over foods, feeds, and agricultural seeds to the Director of Civilian Defense, the role of the Hawaiian Department Quartermaster in civilian food supply was terminated.45

The OFC never attained the importance it would have had if Hawaii had been blockaded by sea, but it nonetheless performed an essential task. Its operations, involving a far-reaching responsibility for the food supply of a friendly population that was virtually without precedent in Army history, showed that under comparable circumstances in the future it would be necessary to anticipate such problems as rationing and price control. Prewar planners had been so absorbed with schemes for shifting the basis of agricultural production from sugar and pineapples to fruits and vegetables that these matters had received little attention. In view of the difficulty of interisland communication, strategic planners should perhaps also have given more study to the food problems of the outlying islands.

Reaction to Japanese Victories, December 1941—May 1942

While the U.S. Army was strengthening its position in the great mid-Pacific outpost of Hawaii and making its brave but futile stand in the Philippines, the Japanese were fast transforming their grandiose scheme for a Nipponese-dominated “Greater East Asia” into a reality. At the time of Pearl Harbor they held in China the rich northeastern provinces, the large coastal cities, and the fertile Yangtse Valley. In the next six months they added to these conquests southeast Asia, Java, Sumatra, the American bases at Wake Island and Guam, the strategically located Australian outpost of Rabaul in New Britain, and numerous small islands in the south and central Pacific that could serve as bases for the defense of their acquisitions and as springboards for further advances.

To halt the southward thrust of the Japanese the Allies had to create a safe supply line from the United States to Australia and New Zealand, the only important sources of supply below the equator. Such a line, in turn, required the establishment of bases on the larger and more strategically located island groups that studded the central Pacific from Hawaii south to the British dominions. In the opening months of 1942, therefore, American ground and air forces, often in conjunction with Allied troops, occupied and transformed New Caledonia, the Fijis, Samoa, and other islands into air and supply bases. In Australia and New Zealand they formed the nuclei of organizations intended to develop these countries into major centers of logistical support for offensive operations aimed at driving the Nipponese from their recent conquests.

Organization of Areas in the Pacific Theater

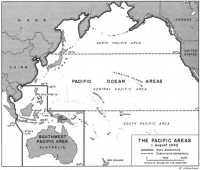

The wide geographical sweep of the war against Japan created so many tactical, administrative, and logistical problems that two major territorial commands, the Southwest Pacific Area and the Pacific Ocean Areas, were established to handle them. The Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA) embraced Australia, New Guinea, the Philippines, the Netherlands Indies except Sumatra, the South China Sea, and the Gulf of Siam, all of which were essential steppingstones on the southern road to Tokyo and all of which, except Australia and southern New

Map 1: The Pacific Areas

Guinea, early fell into Japanese hands. The post of Supreme Commander, Southwest Pacific Area (CINCSWPA), was given to General MacArthur. The geographically vaster Pacific Ocean Areas (POA) included most of the Pacific. (Map 1) It embraced three subordinate areas—the South, Central, and North Pacific Areas. The South Pacific Area (SPA) extended below the equator, east of the Southwest Pacific Area and west of longitude 110° west, and comprised New Zealand, New Caledonia, and the Samoa, Fiji, Tonga, and New Hebrides Islands—roughly Polynesia with the important exception of Hawaii. The Central Pacific Area (CPA), stretching from the equator to latitude 42° north, included the Gilberts, Marshalls, Carolines, and Marianas in addition to Hawaii and most of the Japanese home islands. The North Pacific Area (NPA) covered the whole Pacific above latitude 42° north. Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet (CINCPAC), served as Commander in Chief of the Allied Forces in the Pacific Ocean Areas (CINCPOA). He commanded the Central and North Pacific Areas directly from his Pearl Harbor

headquarters and the South Pacific Area through a subordinate. Both Admiral Nimitz and General MacArthur were responsible to the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington.46

Similar defensive and offensive missions were assigned to the Southwest Pacific Area and the Pacific Ocean Areas. Both commands were to hold those islands that were essential to sea and air communication with the United States, to the defense of North America, and to the launching of operations against the Japanese by sea, air, and land. They were both to prepare and conduct amphibious offensives. In these areas, as in all overseas theaters, the primary mission of the QMC was to support combat operations by furnishing the supplies and services for which it was responsible.

Quartermaster Problems in Australia and New Zealand

In carrying out its mission in the Southwest Pacific Area, the QMC, like other technical services, used Australia as its first great supply base. On that continent from the beginning of 1942 to the close of 1943 were concentrated a major part of the supply activities of the command. Though New Guinea became the chief base in 1944 and was replaced in turn by the Philippines at the beginning of 1945, the southern continent remained to the very end a substantial supplier and distributor of essential military items. To the QMC in particular Australia was important, for the Corps procured a larger proportion of its supplies in that country than did any other technical service. It indeed used that dominion as a zone of interior for the Southwest Pacific in much the same fashion as it did the United States for overseas theaters in general.47

At the outset many problems had to be solved before Australian supply potentialities could be utilized effectively. Internal distribution was impeded by long distances, inadequate railways and highways, and the shortage of coasters. Australian industry, moreover, was not highly developed. Many manufactured items were either not procurable at all or procurable only after industrial plants had been converted to the production of new articles. Primarily, Australia was an agricultural and a grazing land, but even in the procurement of food there were bothersome problems. Meat and grain products, and fruits and vegetables, while obtainable in considerable quantities, were not always obtainable in the quantity and the variety needed by the U.S. Army.48 Vegetable production was conducted almost entirely on small, insufficiently mechanized truck farms and was concentrated near the populous southeastern cities, far from the areas where many American troops were first stationed and even farther from New Guinea. Fruit and vegetable canning and dehydration, essential to the feeding of large field forces, were both in a rudimentary stage of development.

The widespread shortage of manpower hampered efforts to increase production. Of the 7,000,000 people living in Australia, approximately 2,300,000 were in civilian occupations and 1,000,000 were in the armed services. The extent of the shortage of labor

for new or expanding war industries is indicated by the fact that at the close of 1942, roughly 85 percent of the men, 26 percent of the women, and 30 percent of the farm population were either enlisted in the armed services or already engaged in war industries. Available labor consisted almost wholly of men over military age, of the physically handicapped, and of women. Farmers and manufacturers alike had trouble in securing workers. As industry and agriculture expanded, some labor was redistributed in line with shifting wartime needs, and certain types of artisans were released from the Australian armed services. But labor nonetheless remained scarce.49

Transportation, which also presented knotty problems, continued during the first four months of the war to be a responsibility of the QMC. That service alone was charged with the movement of troops, supplies, and equipment by land and by sea. In early March the War Department transferred this responsibility to a Transportation Division in Headquarters, Services of Supply, in Washington, and in mid-April USAFIA General Order No. 40 implemented this decision in the Southwest Pacific Area by shifting transportation functions in that command to a new agency, the Transportation Service.50 But until this directive was issued, and at a few bases and in some military organizations for weeks and even months afterwards, Quartermaster officers carried out regular transportation functions.51

During its period of exclusive responsibility for transportation activities, the QMC busied itself with plans for the military utilization of the Australian railway system. That system was in general incapable of swift distribution of supplies. It had originally been built and developed by the six Australian states to serve state rather than national needs. This fact accounted for the system’s most serious shortcoming—five different gauges. These varying gauges made long-distance shipments impossible without unloading and reloading, occasionally three or four times. Traffic repeatedly became congested; in one instance nearly 20,000 tons of freight were stalled on sidings between Newcastle and Brisbane. Delays were caused also by the lack of motor vehicles for moving accumulated traffic, by the shortage of cranes and other materials-handling equipment, and by the difficulty of obtaining workers for prompt handling of freight by manual means. The delivery of fresh provisions in good condition was particularly difficult, for Australia had developed no national system of distributing perishables and had few refrigerator cars. Fresh produce in consequence deteriorated rapidly.52

Apart from the absence of a single country-wide gauge, the railway system had other weaknesses. Grading was poor; there were not enough sidings, yards, workshops, or water supply points; and signaling was done mostly by hand. Rolling stock was designed to carry loads far below the American standard. Boxcars carried only from about 8 to 15 tons. Australian trains hauled only about 500 tons, as compared with the 4,000 or more tons sometimes handled in the United States, and had an average speed of 15 to 18 miles an hour. The lack of a reserve pool of serviceable locomotives and freight cars further retarded movements.53 Finally, there were not enough lines to serve all militarily important areas. Northern Australia, strategically significant early in 1942 as the probable initial objective of any attempted invasion, had but a single railroad, running south 300 miles from Darwin to Birdum, with a gap of 650 miles between it and the terminus of the central system starting at Port Augusta on the south coast. Darwin was thus almost isolated from the rest of the country.54

So limited was the carrying capacity of the rail system that it could not deliver promptly all the supplies required by military installations. In April 1942 the main line of the Queensland system, running along the east coast from Brisbane to Cairns, had a daily capacity of only 1,000 tons and required twenty days to move a single division of 15,000 men and their supplies. The maximum capacity of the Trans-Australian Railway, connecting Melbourne and Perth, was a mere 400 tons a day. Only in Victoria and New South Wales, the heart of industrial Australia, did freight-hauling capacity approach military requirements. Here two lines, capable of carrying 5,200 tons a day, ran north to Brisbane, but they could not be devoted exclusively to military transportation for more than a few days at a time without crippling the economic life of this rich region upon which the armed services depended for coal, steel, munitions, textiles, and food.55

Motor roads, though compensating in part for railway shortcomings, were neither good enough nor well enough distributed to handle military traffic satisfactorily. Only in heavily populated southern and southeastern Australia, where railways were most efficient and improved highways least needed, could roads carry a dense traffic. Elsewhere they were mostly of a dirt type that swiftly disintegrated under the heavy loads that had to be hauled to American troops stationed at long distances—often several hundred miles—from railways.56 The shortage of suitable trucks further hampered motor transport.

In line with its original mission, the QMC at the outset had responsibility for the procurement, distribution, and maintenance of motor vehicles and their parts and retained these functions until 1 August 1942, when they were shifted to the Chief Ordnance Officer.57 At first the Corps could obtain few vehicles from the United States and could not use many Australian trucks, for they were in general small, few in number,

and usually more than five years old. Most of these trucks, moreover, had power on only one axle, making it impossible to use them in rough country where American two- and three-axle-drive trucks could move easily. Throughout 1942, however, the U.S. forces were obliged to depend to a considerable extent on locally produced vehicles.58

During this period the Corps had practically no means of storing motor vehicles and their parts or of assembling the vehicles that arrived from the United States unassembled or only partly assembled. Nor did it have more than a few trained men capable of repairing trucks. It therefore negotiated contracts with the Australian branches of the American automobile companies for the performance of these essential tasks in the main cities of that country. An interesting feature of these arrangements was the handling of the problem of motor parts. Since these items were then very scarce, the QMC set up parts depots in conjunction with General Motors at Melbourne, Chrysler at Sydney, and Ford at Brisbane. Before these depots were established, it had often been necessary to dump parts in vacant lots at the port cities where, obviously, they could not be properly handled. Once the parts were concentrated in the new depots, they were classified and stored by item and forwarded to requisitioning units. In an effort to provide the means of quickly repairing broken-down vehicles at remote points, even commercial airlines were utilized to speed the delivery of the necessary spare parts. Generally speaking, the three parts depots pointed the way to a solution of the spare parts problem—a problem that throughout the war plagued all technical services issuing mechanical equipment.59

Because of the inadequacies of rail and highway transportation, the Army resorted to water transportation as much as possible. Only at the very outset, when sea lanes were still unsafe, did it ship most of its supplies by land.60 Generally speaking, the eastern ports, despite the shortage of coasters, formed the main supply centers until the northward drive of the Allied forces gave them fairly satisfactory bases in New Guinea and the Philippines. The loading, discharge, and storage of cargoes at Australian ports became a hectic process early in the war because of the shortage of cranes, tractors, trailers, fork-lift trucks, and other materials-handling equipment, and the reluctance of the Commonwealth to relax long-established regulations governing the hours, wages, and employment of port laborers who clung to peacetime practices that slowed supply operations. Many of these laborers refused to work in the rain or handle refrigerated food and many other types of cargo. They objected, with some success, to the utilization of mechanical equipment At times strikes obliged the Army to use service and even combat troops for discharging ships, a measure that stirred the resentment of the stevedoring companies and the longshoremen. Even if troops were not so employed, they sometimes had to be held in reserve for use if it rained during the loading or discharge of badly needed cargo.

The speed and efficiency of handling operations also suffered from the large

Storage Facilities in Australia were at a premium, and buildings such as the small warehouse were utilized until ...

... temporary “igloo” type warehouses could be constructed.

proportion of old and physically unfit men among port laborers and from the high rate of absenteeism, which averaged as much as 18 percent at Townsville. Since double and triple rates of pay were given for week-end work, some longshoremen put in an appearance only on Saturdays and Sundays. So common did this practice become that the Commonwealth, with the concurrence of the U.S. Army, finally stopped all weekend dock operations. Longshoremen, as a group, it was estimated, handled only 6 to 10 tons per gang per hour in early 1943 in contrast to the 18 to 25 tons handled by gangs of American soldiers. In the following two years the dock workers’ average declined by about a third.61 The Quartermaster Corps was concerned with these unfavorable port conditions not only because it had for a time direct responsibility for water transportation but also because its ability to maintain adequate stocks and to distribute supplies and equipment promptly and equitably, like that of other technical services, depended to a considerable degree upon speedy handling of cargoes.

Like transportation operations, storage operations had many adverse conditions to contend with. When U.S. forces first arrived, private storage space was almost completely filled. Wool warehouses were almost the only type of commercial storage available for lease, and they were available only until the new wool season opened in August and September. In the port cities the Australian Army had taken over most of the storage places not needed for mercantile purposes. In the interior, especially at change-of-gauge points, space was even scarcer. From the outset, therefore, the problem of future storage for ever increasing military stocks had to be faced. Finally, in 1943 an extensive building program was undertaken to meet American storage requirements, and a substantial number of temporary structures were built.62 Storage operations were much less mechanized than those in the United States, and modern materials-handling equipment was slow in arriving from the zone of interior. Quartermaster warehousing, though better than elsewhere in the Southwest Pacific Area, never attained as high a degree of efficiency as it did at home.63

In Australia the U.S. Army had to adjust its operations to a new political as well as a new economic scene. While the Commonwealth Government was eager to help supply the American forces, it quite naturally gave prior consideration to its own armed services and its own citizens. As a member state of the British Commonwealth of Nations, it exported substantial quantities of supplies to the United Kingdom. It of course hoped to continue as extensive an export trade as possible. Since all local procurement and much distribution of American supplies had to be carried out through Australian agencies and in conformance with Australian policies, the U.S. Army set up special bodies and procedures to coordinate the relations between its own

supply organizations and those of the federal and state governments of Australia.64

In spite of the unprecedented problems that it posed, Australia was an invaluable asset to the QMC. For more than two years it furnished well over half the food consumed in the Southwest Pacific Area and a substantial part of that consumed in the South Pacific Area. Until the termination of hostilities it poured out rations for American use and supplied clothing, equipage, and general supplies in liberal quantities. Without Australia, the shortage of ocean-going ships would almost certainly have prolonged the war against Japan.

New Zealand, while a less valuable base than Australia, had a higher proportion of arable land, and relative to area and population, provided more food for the armed services. In New Zealand, as in Australia, there were shortages of labor, warehouses, and agricultural and industrial equipment.65 Since the smaller dominion consists almost wholly of two long narrow islands, North Island and South Island, each about 500 miles long and seldom more than 120 miles wide, the chief means of assembling local products was by coasters. These vessels were at first scarce, but enough of them eventually were obtained to meet essential military demands. Like Australia, New Zealand proved of inestimable value to the U.S. Army.

Australia and New Zealand not only provided indispensable supplies and equipment. Under the principle of reverse lend-lease they also paid for them. The detailed application of this principle was first worked out in an informal agreement with the American forces in the spring of 1942. At London, several months later, the United States made a formal arrangement covering all British dominions and colonies in the Pacific. Under this arrangement Australia and New Zealand paid not only for locally procured supplies but also for such local services as the repair of shoes and typewriters, the dry cleaning and laundering of clothing, and the provision of water, gas, and electricity. In addition these countries bore the cost of building warehouses and other structures for the U.S. forces and paid the wages of civilians employed by American installations. Eventually, reverse lend-lease was applied also in the French possession of New Caledonia, but, owing to local opposition, not until early 1944. Through the application of this system of local procurement the United States received partial compensation for the millions of dollars that it expended for American products needed by its Pacific allies.66