Chapter 13: Rear Area Support on the Continent: Operations

The operating agencies of the Communications Zone, responsible for moving supplies forward and delivering them to the combat units, were territorial subdivisions known as base sections, intermediate sections, and advance sections. Base sections on the Continent had almost exactly the same function as those in the United Kingdom. Intermediate sections also remained very much the same, except that they received supplies from a base section instead of from a port, and sometimes provided direct support to combat troops. Advance sections were direct-support agencies which concentrated their operations at the boundary between the communications zone and the combat zone. During an advance they were in constant motion, taking over and expanding the supply installations abandoned by the armies. Under such circumstances an advance section was primarily a traffic expediting and reconsignment agency, which only engaged in storage and distribution activities to a very limited extent. In a static situation, an advance section operated very much like an intermediate section. The European theater ultimately included two advance sections: the Advance Section, Communications Zone (ADSEC) which landed in Normandy in June 1944 and supported the 12th Army Group; and the Continental Advance Section, Southern Line of Communications (CONAD), which landed in southern France two months later and supported the 6th Army Group.1

Advance Section

According to plan, personnel of ADSEC were attached to the supply echelons of First Army, and began to arrive in Normandy about D plus 10. First Army retained control over its own logistical support as long as geographically feasible, and the ADSEC Quartermaster staff under Colonel Zwicker spent the first month on the continent largely observing supply operations under combat conditions. Gradually, ADSEC began to take over installations, first at Cherbourg and later on the beaches, while the armies readied themselves to break out of Normandy.2

Inextricably concerned with ADSEC’s mission, Littlejohn visited the

beachhead repeatedly in June and July. The First Army, with its front lines still almost in sight of the beach, relinquished its supply responsibilities grudgingly, one at a time. The commander of the Provisional Engineer Special Brigade Group, a brigadier general, retained many Quartermaster functions that should properly have been assumed by Colonel Zwicker. The result was that depots were located at the sites of the original dumps and that they were arranged primarily to speed the turnaround of amphibious trucks (DUKWs), but without regard for segregation and inventory of quartermaster supplies. Statistical control over supply had disappeared. Littlejohn temporarily appointed himself quartermaster of ADSEC to solve the command problem, but the damage had already been done. Certain categories of scarce but important quartermaster items became lost and were not found for eight months.3 After his third trip to the Continent, on 16 July, Littlejohn got Col. John B. Franks, the FECZ quartermaster, also to serve as acting quartermaster of ADSEC. He felt that on the eve of the crucial COBRA operation to break out from the constricted beachhead the ADSEC Quartermaster Section required aggressive leadership. Colonel Zwicker’s extensive Quartermaster experience could be better utilized as a combat observer and as a judge of Quartermaster equipment under combat conditions. He was therefore made chief of the Research and Development Division of OCQM.4

Littlejohn found faults in his own staff as well as in ADSEC. One of the first QM base depot companies to reach the far shore reported the arrival of 11,073 corn brooms and 12,789 cotton mops, enough to sweep the battlefield. It questioned the immediate usefulness of 5,269 large garbage cans and 32,616 reams of mimeograph paper at a time when the main need was for rations, POL, and combat clothing. The Chief Quartermaster demanded more care and better judgment in the mechanics of quartermaster supply.5

Support of the Armiesin the Pursuit

On 1 August, when the 12th Army Group and the Third Army became operational, ADSEC was detached from the First Army and assumed responsibility for support of both First and Third Armies through the 12th Army Group. By this time the breakout from the beachhead had succeeded, the armies were picking up speed, and ADSEC was soon hard pressed to follow them. It moved forward three times in as many weeks, establishing successive headquarters and supply installations at Le Mans on 20 August, Étampes on 31 August, and Reims on 8 September. What this pace meant to the Quartermaster Section can be more fully appreciated by realizing that the life of the average Class I and Class III supply point during this turbulent period was sixteen and ten

days, respectively.6 These sites were in fact little more than transfer points where supplies, largely operational rations and POL, were quickly relayed to eager and poised combat units. Two QM base depots, the 55th and 58th, worked feverishly to support ADSEC. At the end of August, when according to plans supplies should have been building up in the advance depots, 90 to 95 percent of continental supplies still lay on the beaches, 300 miles behind the army dumps. To complicate the situation further, ADSEC’s transportation facilities were inadequate to meet the full needs of the combat units and the armies had to send some of their own vehicles back to the beaches as well as to the ADSEC transfer points.7

Colonel Smithers, the new ADSEC quartermaster, called for able and aggressive POL experts to aid him in this, the most important aspect of his mission. As usual at this level, information on what supplies would arrive, when, and where was even more important than the mechanics of unloading and forwarding. Smithers found that for lack of a liaison officer with the Transportation Corps to provide such information, the ADSEC G-4, a staff officer who should not have engaged in operations, was invading his domain and creating considerable confusion. The ADSEC quartermaster also wanted about 2,000 POW’s to expedite unloading of trains and trucks. The OCQM was able to meet his re-quests.8

As evident in retrospect, there was not only feverish activity at ADSEC headquarters, but also a strong feeling of frustration and exasperation with COMZ headquarters because of its consistent overoptimism and failure to deliver. It was quite true that combat needs were not being filled and that ADSEC’s efforts met with angry recriminations from various tactical headquarters. This state of affairs was inevitable, since German resistance was slight and the senior Allied commanders had placed no limitation whatever upon the advance of the combat forces. On 27 August, Bradley’s official instructions read in part: “It is contemplated that the armies will go as far as practicable and then wait until the supply system in rear will permit further advance.”

In other words, a breakdown of the supply system had been anticipated and even courted. Littlejohn was not a party to this controversy but found deficiencies in both headquarters. Certainly he held no brief for the G-4, COMZ, whose rigid system of controls and slow response to changing conditions had put a straitjacket on Quartermaster operations. But he held that ADSEC was not content merely to advocate the point of view of the combat units: it actually tried to act like a combat zone organization and carried the principles of close support and extreme mobility much too far. In particular, he criticized its efforts to operate exclusively as a reconsignment agency and its patent lack of interest in establishing large or efficient dumps. This weakness was particularly evident during the period of static warfare in September–November 1944, when the OCQM had to step in and assume direct command over the two QM base depots

newly located in ADSEC territory at Liège and Verdun.9

The Red Ball Express

In a desperate effort to bridge the widening gap between the armies and the stocks in Normandy, the ADSEC Motor Transport Brigade and the Transportation Section, COMZ, jointly inaugurated the widely publicized Red Ball express on 25 August 1944. The decision to pursue the enemy beyond the Seine had still further inflated combat requirements; the immediate need was now estimated at 100,000 tons (exclusive of bulk POL) to be delivered to the Chartres-Dreux area by 1 September. The railways could haul less than one-fifth of these supplies and planes only about 1,000 tons per day. Trucks would thus have to move more than 75,000 tons, mostly from St. Lô to Chartres, in seven days. This objective was not quite achieved, but the Red Ball express did demonstrate that it was an effective instrument at a time of extreme stringency in transport. Starting with 67 “Quartermaster” (actually Transportation Corps) truck companies of ADSEC, it reached a peak on the fifth day of 132 companies with nearly 6,000 vehicles, which moved 12,000 tons. These included provisional truck companies formed from engineer, heavy artillery, chemical, and antiaircraft artillery troops. Three infantry divisions were immobilized, all their vehicles going to Red Ball. These units provided a steady stream of fast freight vehicles which rumbled over reserved one-way highways twenty-four hours a day, averaging twenty-five miles an hour. On 10 September the route was extended, forking at Paris to serve the Third Army at Sommesous and the First Army at Soissons (later extended again to Hirson).10

The scale of these motorized operations was a complete surprise to the enemy and upset his calculations, but there were also disadvantages. The operation required a very heavy overhead of military police, engineer road maintenance crews, ordnance automotive repair units, signal troops and equipment, and specialized supervisory personnel. Attrition of equipment was very great, especially among the untrained provisional units. Some of them neglected preventive maintenance to the point where they were derisively called “truck destroyer battalions.” Moreover, on the extended routes Red Ball vehicles daily consumed about 300,000 gallons of gasoline and wore out more than 800 tires. As the commander of the COMZ Motor Transport Service observed, trucks can haul whatever the railroads do, but at a much greater cost in manpower and equipment. Red Ball, begun as a desperate gamble to hasten victory, had to be continued until other transport means could support the combat units in their extended positions on the German frontier. It was terminated in mid-November as soon as large-scale rail and barge facilities became available.

Littlejohn’s objections to excessively rigid control of all transportation by the

G-4, COMZ, applied with particular force to the Red Ball operation. At the time, this was the only effective means of getting supplies forward, and the Chief Quartermaster contended that all the technical services should have had a voice in deciding how Red Ball tonnage was to be utilized. The Motor Transport Brigade should have been concerned exclusively with such matters as traffic control, highway discipline, and motor maintenance. Actually, as the chosen instrument of the G-4 at COMZ and in the headquarters of the armies, the brigade also exercised authority over supply at the initial and final Red Ball traffic control points. Attempting to interpret broad policy as best they could, officers of the brigade were making decisions on supply priorities and final destinations. The results were impressive tonnage statistics, accompanied by a regrettable lack of selectiveness in the supplies moved forward. Some of the Red Ball trucks could more profitably have been allocated for use within the coastal dumps and depots to rearrange their disorderly heaps of unsorted supplies. Such action would have gone far to insure that the supplies received by the armies were those that had been requisitioned.11

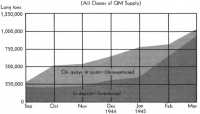

Progress of the Build-up

Vitally interested in ADSEC’s forward movement, the OCQM maintained a careful surveillance of the rapidly shifting supply situation through its system of liaison visits and reports. The activation of new base sections kept pace with the pursuit even though supplies did not. For example, the original Red Ball route was entirely within ADSEC territory, since Normandy Base Section had not yet taken over the St. Lô area, but by 1 October the route passed through five different sections. (See Table 12.)

To implement its own forwarding program, less spectacular than Red Ball but possibly of equal importance, the OCQM transferred to ADSEC and to the new base sections experienced QM base depot headquarters, railhead, service, and depot supply companies over the protests of commanders in Normandy, Loire, and Brittany Base Sections. They were replaced by green units from the United Kingdom and by many prisoners of war. Littlejohn asked the Provost Marshal to delay shipping POW’s to Great Britain until the needs of the technical services on the Continent had been met, and he then insisted that each base section quartermaster put in a request for several hundred, warning them they would soon lose most of their service companies.12

Unfortunately, the critical situation in regard to land transportation was accompanied by a simultaneous crisis in port capacity, which was also largely ignored by the tactical commanders. Although not explicitly stated, Bradley’s objective in late August 1944 was undoubtedly the Rhine, as already noted, which the 12th Army Group actually reached in

February 1945. How overoptimistic this objective was can be illustrated by comparing the 12th Army Group’s estimated requirements and COMZ capabilities at the end of September. On the 25th, the army group G-4 estimated that the field forces would require 650 tons per division slice per day. Currently, there were 10 divisions in the First Army, 8 in the Third, and 2 in the Ninth—a total of 20. Adding the requirements of ADSEC and Ninth Air Force, and including the contemplated build-up, brought the total to 18,800 tons a day in early October (22 divisions); 20,750 tons in late October (25 divisions); and 22,700 tons by 1 November (28 divisions). Other ETO requirements were not included. The G-4 estimated that an additional 100,000 tons would be required by November to meet deficiencies in equipment and build up a reserve of three days of all classes of supply. He inquired how soon COMZ could deliver the additional 100,000 tons and also establish depots in ADSEC that could maintain the armies.13

The COMZ reply was most discouraging; even using the more frugal SHAEF figure of 560 tons per division slice would mean a deficit below daily maintenance for the proposed forces all through October. COMZ planned to build up 10,000 tons of reserves for the First Army in October and 20,000 more in early November, but only at the expense of daily maintenance for the other armies. The required 100,000 tons might be available at the end of November. Even this estimate proved overly optimistic, based as it was largely on an impossible 20,000 tons per day from Cherbourg and the beaches. Actual discharge there was about 12,000 tons per day in October and 14,300 in November. A surprising 6,000 tons a day from Le Havre and 2,000 tons from Rouen, achieved by the end of October, allowed Bradley to maintain 23 divisions after a fashion, although fortunately only 13 were actively engaged in combat.14 The troop build-up had outstripped port capacity as well as overland forwarding capacity. Clearly, everything now depended on the opening of Antwerp, a tremendous port capable of maintaining all Bradley’s divisions, and Montgomery’s as well. Moreover, it was a port in an advanced location, practically on the edge of the combat zone. The following comparative mileages emphasize dramatically the advantages of Antwerp: Cherbourg to Liège, 410 miles; Antwerp to Liège, 65 miles; Cherbourg to Nancy, 400 miles; Antwerp to Nancy, 250 miles.

Advance Depots

In the course of its advance across Europe, the Quartermaster Section of ADSEC operated about 175 storage and service installations of all types in five countries, most of them for periods of less than 60 days. Nearly half of these were POL sites, and approximately a quarter were Class I sites. Salvage, laundry, and baths were also important activities of ADSEC, but for several reasons it handled only small quantities of Class II and IV supplies. During the early stages of continental operations these items had low priorities and few arrived. Later, the specific needs of the combat troops in clothing and

equipment were shipped to them direct without being stored in advance depots.

After the impetus of the pursuit was checked in mid-September 1944, ADSEC settled down for nearly six months to a more static type of operations. On 1 October, Class I and III depots were opened at Liège (Q-179) and Verdun (Q-178). On paper, their initial Class I missions were eight million A rations each, but supplies arrived slowly, and ADSEC was not experienced in the operation of large fixed depots. An improvement in transportation and the loan of supply specialists from the OCQM made it possible for these depots to begin supplying the field armies late in November. During the next five months each depot handled daily averages of Class I and III supplies approaching seven thousand tons.15

Since size tariffs made distribution of clothing complicated and multiple depots were wasteful, Littlejohn believed that Class II should be handled for all the armies at a single large depot under close supervision. At his direction Q-180, the first large inland Class II and IV depot, was established at Reims on 1 October. Reims was in ADSEC territory at the time, but it was transferred to the jurisdiction of Oise Intermediate Section before the end of the month. Although later surpassed in storage capacity by Charleroi-Mons, Q-180 at Reims, commanded by Col. Carroll R. Hutchins, remained the major active distribution depot for clothing in the ETO until after the end of hostilities. Situated at a rail junction, it could support the First and Ninth Armies advancing through Liège to the lower Rhine and the Third Army moving through Verdun to the Saar. To increase its potential, Littlejohn set up Q-256, a separate salvage and clothing repair depot, also at Reims. Both these installations employed very large numbers of POW’s; in fact Q-180 was operated largely by some 10,000 Germans, headed by a captured colonel. The American supervisory and security staff at Q-180 was limited to the 55th QM Base Depot and attached personnel—a total of less than 300—commanded by Colonel Hutchins.16

Liège and Verdun, handling Class I and III supplies, and Reims, responsible for Classes II and IV, formed a strategic triangle to provide advance support for the 12th Army Group. This was the heart of Littlejohn’s organization to back up the main combat effort in the ETO. He had proposed this plan to the COMZ G-4 as early as mid-September, but at that time neither supplies nor Quartermaster operating units were available. Liège Depot was commanded by Col. Mortlock Petit. In December, its mission was expanded and redefined as 40 days’ rations and 13 days’ POL for 925,000 men of First and Ninth Armies. Verdun was commanded by Col. Roland T. Fenton; it was to support 450,000 men of Third Army with 40 days’ nonperishable rations, 22 days’ cold stores, and 16 days’ POL. Reims was to provide 40 days Class II for 2,225,000 men. These included the three armies, Ninth Air Force, ADSEC, and some 300,000 non-U.S. troops.17

Until the end of 1944 this triangle was

supplied mainly through Cherbourg and Le Havre. The German Ardennes offensive, directed largely against Liège, succeeded neither in capturing that city nor in cutting the supply lines to these depots. After Antwerp began large-scale operations in late December, it supplied much of Liège’s needs, but Verdun and Reims were still partly dependent on Cherbourg, Rouen, and Le Havre. Early in April ADSEC moved forward into Germany and the Liège and Verdun depots were turned over, respectively, to Channel Base Section and Oise Intermediate Section. Thus in theory the triangle had become an intermediate depot system, but ADSEC was racing across Germany after the victorious armies and never had time to set up more than temporary distributing points. Reims, Verdun, and Liège (along with Q-186 at Nancy, supporting CONAD) therefore actually continued to be the forward depots of the ETO until after the German surrender.18

The final campaign in Germany confirmed the experience gained in the pursuit across France: advance depots provided necessary reserves and take-off bases for a pursuit, but the depots themselves could not be moved forward until after the pursuit had ended. The sixty-day interval between the date of formal activation of depots at Verdun and Liège and the time when they actually began to support the armies represents the crux of the problem. Since the Communications Zone could not operate at full capacity and extend itself at the same time, the expansion had to take place in the combat zone. Air transport could and did provide considerable relief, but did not solve this problem.19 By the end of World War II the Allied armies had greatly improved their mobility, even surpassing their German models in this respect, but geography still imposed a definite limit upon the duration of an uninterrupted pursuit.20

Base Sections and Base Depots

Located behind ADSEC were the base sections and their depots, the major installations engaged in large-scale storage and wholesale distribution operations. A base section was a comparatively static organization which, unlike ADSEC, did not continually move forward as the troops advanced. Rather, separate base sections were designated for the various areas to be liberated, and each was brought in to take over installations left behind by ADSEC. The RHUMBA plan, originally called Reverse BOLERO, provided that the continental base section system would be organized by progressive transfer of the United Kingdom base

sections to the far shore.21 Personnel in the Eastern Base Section in Great Britain were earmarked for Base Section 1 on the Brittany Peninsula, which was expected to bear the main burden of logistical support for the American forces. Another headquarters was formed in North Ireland, activated as Base Section 2, and designated to assume control of supply in the Cherbourg area.

In the first six months on the Continent, six base sections—one more than originally planned—were established along the northern line of communications. The main axis of supply developed from Cherbourg and the beaches instead of from Brittany as anticipated. Until Antwerp could be opened, the British made Le Havre and Rouen available to the U.S. forces—an arrangement that actually lasted until after V-E Day. Use of these ports involved setting up Channel Base Section, an organization within the British administrative zone, and therefore with very limited territorial functions. An extra headquarters was available for this purpose because Cherbourg Area Command, which had demonstrated its abilities under difficult conditions in the original lodgment area, was reinforced and designated Cherbourg Base Section. (Table 12)

The organization of the Quartermaster staff in a base section was much simpler than that of the OCQM, though all of the essential services were provided for. All the commodity responsibilities came under a consolidated Supply Division, with subordinate branches handling storage and distribution and the various classes of supply. Services were handled by an Installations Division. Since the base section quartermaster’s problems involved coordination of activities in the scattered depots, dumps, distributing points, and other field installations, the Field Service Branch, acting as liaison and troubleshooting agency, was extremely important.

Like all senior Quartermaster organizations, the base section QM staffs were plagued by shortages of trained manpower. Before D-day, a T/O of 33 officers and 88 enlisted men had been authorized, and ADSEC actually attained this strength for a brief period. But continental base sections were organized considerably faster than U.K. bases were inactivated, and the available personnel had to be shared. Late in August Littlejohn proposed to break up Base Section 3 and form three “Class I QM Base Section Staffs.”22 With 11 officers and 25 enlisted men each, he considered them adequate for initial operations of Normandy, Brittany, and Paris (Seine) Base Sections. He felt that ADSEC could operate as a Class II staff with 23 officers and 60 men.23 By V-E Day, the average official strength of a base section was about. 75 persons. There were usually a good many more actually present, for from the first it was planned to attach a QM group to each staff, and as they became available one or more base depot headquarters companies were assigned within each base section.24 (Appendix B)

Table 12: Base, Intermediate, and Advance Sections

| Section | General Area of Responsibility | Headquarters | Date Activated | Inactivated or Absorbed |

| Advance Sec (ADSEC) | Area immediately behind 12th Army Group° | Catz (France), Le Mans, Etampes, Reims, Namur (Belgium), Bonn (Germany), Fulda | 18 Jun 44 (operational), 1 Aug 44 (released by First Army) | Inactivated 15 Jul 45 |

| Normandy Base Sec (NOS) | Normandy; absorbed BBS and LBS and acquired Rouen—Le Havre area From CBS 1 Feb 45 | Cherbourg, Deauville | 21 Jul 44 (as Cherbourg Command; redesignated NBS 16 Aug 44) | Absorbed by CHANOR 1 Jul 45 |

| Brittany Base See (BBS) | Brittany (later absorbed LBS) | Rennes | 16 Aug 44 | Absorbed by NBS 1 Feb 45 |

| Seine Sec | Paris and environs | Paris | 24 Aug 44 | Became subsection of OIS 2 Jul 45 |

| Loire Base Sec (LBS) | Between BBS and left bank of Seine | Le Mans | 5 Sep 44 | Absorbed by BBS 1 Nov 44 |

| Channel Base See (CBS) | Rouen–Le Havre; later shifted to Belgium | Le Havre, Lille, Brussels | 10 Sep 44, 1 Feb 45 (lost Le Havre to NBS) | Absorbed by CHANOR 1 Jul 45 |

| Oise Intermediate Sec (OIS) | Area between Seine Sec and ADSEC; later absorbed all ADSEC and CONAD territory | Reims | 15 Sep 44 | † |

| CHANOR Base Sec | Former CBS and NBS territory | Brussels | 1 Jul 45 | † |

| Continental Advance Sec (CONAD) | Area immediately behind 6th Army Group’ | Dijon, Nancy, Kaiserslautern | 1 Oct 44 | Inactivated 15 Jul 45 |

| DELTA Base Sec | Rhône Valley and all SW France | Marseille | 1 Oct 44 | † |

| Burgundy District (of CONAD) | Burgundy, Lorraine | Dijon | 9 Feb 45 | Absorbed by OIS 21 Mar 45 |

* ADSEC and CONAD began to operate exclusively in Germany on 1 and 7 April 1945. respectively. On those dates they transferred territory in Allied countries to Channel or Oise Sections. Territorial functions within Germany were performed by armies, not by advance sections.

† Continued to operate during 1945–46 for redeployment and support of U.S. forces in Germany.

Source: Administrative and Logistical History of the ETO. pt. II, vol. II pp, 187-201. OCMH.

When a new base section became operational and prepared to assume control of branch installations released by ADSEC, the various technical services hastened to make contact with their opposite numbers in ADSEC for orientation on the logistical and tactical situation. They would normally confer with the G-5 (civil affairs) officers and town mayors regarding additional storage and depot sites, salvage and cold-storage facilities, marshaling yards, and the exact location of abandoned or captured enemy material. It could usually be assumed that ADSEC had made a hurried beginning of such activities, which would now be carried out more thoroughly. The degree of cooperation between quartermasters of a base section and ADSEC was variable. During the pursuit, ADSEC gave incoming base section personnel no more than a very hasty briefing. But when Oise Intermediate Section “understudied” ADSEC at Reims during most of October, several of the incoming base section officers and noncommissioned officers were taken on temporary duty for informal training with ADSEC, and for a time each section supplied the other’s troops when storage sites or stock levels made such an arrangement advantageous.25

Such a smooth and orderly transition was exceptional. Indeed Littlejohn questioned the validity of the whole ADSEC concept. He doubted that a headquarters that was “always rushing off somewhere” could give efficient direction to a territorial type of organization. The “understudy” concept was useful, but when an additional base section was needed, the understudy, rather than the original base section, should move forward to administer it. A permanent base section immediately behind the combat zone, which was not preoccupied with trying to retain its mobility, could establish really large dumps at the outset and give efficient support from them. Thus the armies would not be tempted to establish large dumps of their own—as actually occurred in the ETO, seriously disrupting supply operations.26

Brittany Base Section

In Brittany, where ADSEC had not followed the tactical units, the Quartermaster Section, Brittany Base Section, had to search out its own depot locations. Here, also, the base section staff selected minor ports for temporary use, and arranged for the development of port storage and transshipment facilities. For example, even before the reduction of Brest, the base section quartermaster took the initiative in developing north shore offloading potentialities at Morlaix, St. Michel-en-Greve, St. Brieuc, and St. Malo. The capacities here were small; Morlaix, the largest of the four ports, could anchor only seven Liberty ships and handle but three thousand tons per day, and St. Brieuc was limited to coasters with no more than a ten-foot draft. By 23 September Brittany Base was getting its Class I supplies from Morlaix and was preparing to relieve the

congestion on the Normandy beaches and at Cherbourg.27 But if Morlaix sought to take pressure off Cherbourg, it soon encountered its own difficulties. In the absence of equipment for the steady unloading of vessels, railroad cars had piled up. Littlejohn found the plan whereby Morlaix was to feed six daily trains into the Red Ball program for the support of forward areas wholly unrealistic and directed that his Storage and Distribution Division consult him before issuing such orders to base sections. This was but one example of inflexible thinking and stubborn adherence to plans made before D-day. Clearly, Brest was not available as a port and Morlaix would barely be able to make Brittany self-sufficient in Class I supplies.28 Developments in Brittany Base Section, commanded by Brig. Gen. Roy W. Grower, illustrate admirably Littlejohn’s thesis that even territorial organizations had to maintain a certain mobility and flexibility under modern conditions and be prepared to break the precedents of World War I. Patton’s Third Army had swept through Brittany in August and left VIII Corps behind to reduce the coastal fortresses Brest was finally captured on 19 September, after four weeks of intensive siege but the port was virtually useless. Combat operations in Brittany had been supported largely from the Cotentin, involving a westward movement of supplies, instead of the eastward movement planned before D-day. Meanwhile Ninth Army had been activated and had assumed control of VIII Corps on 5 September, remaining in the area until it was transferred to Belgium early in the following month. Brittany absorbed Loire Base Section on

November, but even the enlarged unit was an inactive backwater; while the main current flowed from Cherbourg northeastward, the depots at Rennes and Le Mans remained nearly empty. The Brittany Base Section staff turned over its territory to Normandy Base Section on 1 February 1945 and eight days later assumed command of the Burgundy District, with headquarters at Dijon, thus permitting CONAD to move forward to Nancy. Burgundy District was transferred to Oise Intermediate Section on 2 April, and on 7 April it assumed control over all territory formerly administered by CONAD. A bit later it was renamed Lorraine District after the newly acquired territory.29

Miscellaneous Base Section Responsibilities

In addition to supporting the COMZ and Air Forces personnel stationed in rear areas, the base sections also had certain direct responsibilities for Ground Forces personnel, both units and casuals. The temporary location of Ninth Army in Brittany Base Section has already been mentioned. Late in December the Fifteenth Army was activated and assumed

a similar role over the forces hemming in the German garrisons on the lower Loire. But this was incidental; the army’s main duty was to serve as a headquarters for U.S. units in the SHAEF reserve, and to stage, equip, and train new units entering the Continent. Each of these responsibilities required considerable assistance from the base sections and their Quartermaster elements.

The Red Horse staging area, with a capacity of 70,000 men, was formally designated as the main installation of this type on 26 October 1944. During succeeding months various camps, all in the Rouen–Le Havre area, were built up to a total capacity of 138,000 men. Camp Lucky Strike near Dieppe, used principally for staging units from the United States, was the largest. Camp Twenty Grand near Rouen was both a staging area and a replacement depot, and other installations in the area specialized in processing personnel going to the United Kingdom on leave and to the zone of interior on rotation. These were large and unexpected commitments and the OCQM was hard pressed to provide camp equipment. British cots and other accommodation stores were forwarded in large quantities, and also British and Spanish blankets, which had not been considered suitable for combat. Littlejohn felt that a requisition from the Quartermaster, Channel Base Section, for 2,500 field ranges, submitted quite without warning at a time when maintenance parts for this item were a major problem, betrayed a lack of contact with reality. He promised to obtain whatever substitutes were available, and authorized the Channel Base Section quartermaster to make local purchases. Moreover, he pointed out that men passing through the areas were field soldiers and presumably able to improvise.30

With its headquarters at Reims, the Fifteenth Army, commanded by Maj. Gen. Leonard T. Gerow was admirably situated to insure that Depot Q-180 at the same location provided the necessary Class II and IV equipment for newly arrived units. Its training installations were scattered all through the rear areas. Beginning late in January 1945, many of these functions came under Lt. Gen. Ben Lear’s Ground Forces Reinforcement Command. This high level theater-wide organization was largely concerned with reassignment and retraining of ETO personnel to provide an adequate number of infantry riflemen. Casualties in this category had been far higher than anticipated, and all ETO organizations —including the QMC—had to provide their share of able-bodied troops. The COMZ quota was increased from 5,750 men in December to 17,700 in March. Theoretically, limited-service personnel were to replace the men “combed out” for infantry service, but these replacements were always slow to arrive, which made the manpower losses even more serious for the technical services. On 31 March, the commanding general of ADSEC reported that losses from this cause had reduced the efficiency of his supply units by 18.8 percent. During March and April the QMC lost all able-bodied replacements except a few highly qualified specialists, but otherwise the losses were disruptive rather than

numerically serious. For example, all members of salvage units were considered exempt specialists, but several service units suffered such heavy drafts that they could not operate at all. The Oise Section quartermaster reported at the end of March that he had lost 469 general assignment men and had received 245 limited assignment replacements. But personnel were called out at the beginning of the month and replaced toward the end of the month, so the actual loss of effective manpower was considerable. However, the end of hostilities curtailed the reconversion program. The OCQM had estimated that by June it would impair the efficiency of ETO Quartermaster operations by as much as 40 percent.31

In April the Fifteenth Army moved into Germany, where it assumed occupation duties west of the Rhine to decrease the 12th Army Group’s security responsibilities. In the same month the Assembly Area Command (AAC) was activated at Reims under Maj. Gen. Royal B. Lord to assume control over redeployment after the fighting was over. Thus its duties were strikingly similar to those relinquished by the Fifteenth Army and it controlled much the same complex of camps and staging areas as well as several large transient camps built near Reims. To support these installations, Q-180 and Q-256 had to expand their activities despite the fact that many of their own subordinate units were also being redeployed. By July 1945, these two depots had a strength of 57,000 men, of whom only 6,700 were Americans.32

Main Depots

The story of base section operations cannot be separated from that of the main depots, for such depots carried out the actual task of wholesale and retail distribution of quartermaster supplies. Plans for the move to the Continent had involved abandoning the general depot in favor of branch depots as already described. According to contemporary official doctrine, a general depot had to be concentrated in a small area to operate efficiently. Even in the United Kingdom, where conditions were far from ideal, the installations of a general depot were usually all within a ten-mile radius. But Littlejohn argued that a system of branch depots permitted greater dispersion and decreased vulnerability to air attack. Moreover, intelligence sources reported that limited storage facilities on the Continent would seldom permit the establishment of large concentrated installations. Branch depots evolved into elaborate administrative organizations on the Continent, each one controlling many subinstallations scattered over a wide area. Also, the shortage of administrative personnel was a major consideration. In a branch depot, technicians could handle command functions also, an important saving in trained QMC officers, whereas in a general depot a separate depot commander was needed.

As a contribution toward BOLERO in 1942, the OCQM had provided most of

the overhead for a General Depot Service,33 only to lose these well-trained men permanently to the evolving U.K. base sections. In the spring of 1944 the designated commanders of future continental base sections cast covetous eyes on the newly authorized Headquarters and Headquarters Company, QM Base Depot. On 19 May, Littlejohn wrote these commanders that the new units would not be available as overhead for general depots on the Continent. He declared that “Branch depots, distributed over wide areas and receiving direct orders from ... the Chief of Service, have been determined to be the most efficient type of organization.”34 Naturally, the base sections were opposed to this idea. They repeatedly proposed a return to general depots as an alleged cure for the never-ending distribution difficulties of an active campaign, and usually received some support from the G-4 Division of COMZ. Probably the most plausible case was advanced by Brig. Gen. Charles 0. Thrasher, the commander of Oise Intermediate Section, who proposed the establishment of a general depot at Reims in November 1944. Every technical service had installations in the area at that time, and thus the change would have been largely administrative. Littlejohn retorted that his plans called for only a Class II depot at Reims. He pointed out that the situation at Reims was fluid and should be allowed to remain so to meet the future demands of the tactical situation. A general depot, he maintained, lacked mobility. Though Thrasher’s proposal was shelved, it was never completely abandoned.35

How the establishment of main Quartermaster depots followed the axis of advance is most clearly apparent from the trail of the American armies as they moved south and east in the summer and fall of 1944. The line, Cherbourg, Rennes, Le Mans, Paris, Reims, Liège—with a major subsidiary, Reims, Verdun —generally described the inland axis of communications. As this line lengthened, measures were also taken to develop the Channel ports and those parallel depots at Le Havre, Charleroi, and Lille, from which supplies could be brought in along the left flank.36

Of necessity, OCQM revised the depot plan repeatedly in order to fit the unfolding tactical situation. Operation OVERLORD may be regarded as having terminated on 24 August, when the armies closed up to the Seine eleven days ahead of schedule. But that landmark went unnoticed in the forward rush that carried troops eastward across 260 phase-line days in 19 actual days.37 Understandably, the over-all plan that Littlejohn requested from his staff on 31 August reflected some of the heady optimism of the SHAEF G-2, who considered “the end of the war in Europe within sight, almost within reach.” That

11th Port, Rouen, showing a variety of supplies stored in the open. December 1944.

opinion goes far to explain a proposal by Littlejohn to locate main depots at Paris, Metz, and Koblenz, despite the fact that only the first of those three cities was in Allied hands.38

Although the details of the new plan were overoptimistic, it was clear that current plans were nonetheless badly outdated. When the front lines were 150 miles east of the Seine, a principal storage area in Brittany was useless. The demand for revision was all the more urgent because, amazingly, Brest was still in German hands. By the time the stubborn defenders had demolished the port and finally surrendered on 19 September, Antwerp had been occupied by the British for two weeks. Moreover, there had been no fighting in the area so that Antwerp, one of the great ports of the world, was intact except for the continuous but haphazard damage of flying bombs. But here was another disappointment; access to the sea, fifty miles in a straight line and twice as far down the winding Schelde estuary, was blocked by fortified German positions. Meanwhile Antwerp’s civil population, even its 20,000 skilled dock workers, were merely a liability and a problem for G-5. Both SHAEF headquarters and the logistical planners required time to comprehend all the implications of this situation. During October Eisenhower became both impatient and alarmed by Montgomery’s preoccupation with the unsuccessful MARKET operation at

Nijmegen, and his neglect of the Schelde estuary. To a logistician, the eighty-five-day interval between the capture of Antwerp and its opening to Allied shipping was the most unfortunate development of the European campaign—the bitter fruit of a decision hard to understand in retrospect. There is some evidence that the enemy understood the importance of major ports better than the Allied command.39

Rouen had been captured on 30 August, but here too the Germans held the Seine estuary and the port of Le Havre. After a stubborn defense involving much damage, Le Havre fell to the British on 12 September. Despite the damage, this port was a valuable prize for reasons of geography. The plans officer of G-4, SHAEF, noted that every 5,000 tons discharged there instead of at south Brittany ports would save the equivalent of seventy truck companies in vehicle turnaround time.40 Although Le Havre and Rouen were in the British zone, Maj. Gen. Charles S. Napier, the British officer in charge of movements and transportation at SHAEF, recommended on 11 September that they be turned over to the U.S. forces, since Dieppe and Calais had also fallen into British hands. But conflicting recommendations from various headquarters as to whether to develop Brest or Quiberon Bay or wait for the opening of Antwerp delayed a clear-cut decision on use of Engineer and Transportation Corps units for rehabilitating the Seine ports.

Meanwhile temporary dumps were located where the need was greatest and tentative depot plans, reflecting current optimism or pessimism and the latest tactical gains or losses, followed one another without time to implement any of them. In retrospect it appears that most of these depot plans suffered from overoptimism. Although true intermediate depots such as Rennes, Le Mans, and Paris had been established, they remained of minor importance. As much transportation as became available was used to concentrate stocks in such forward depots as Nancy, Verdun, and Liège, with the expectation that with continued tactical successes, they would soon become intermediate depots. This is the essential element of the OCQM supply plan published on 1 December 1944.41 (Table 13)

Actually, despite optimism all through the autumn, there were no outstanding Allied successes until March 1945, and meanwhile the lack of a supply system echeloned in depth hampered support for the combat forces. The most serious deficiency was at Liège. For lack of a base installation at Antwerp, this site had to function simultaneously as base, intermediate, and advance depot all winter. General Somervell, who visited the ETO in January 1945, pointed out these defects, and laid most of the blame on the system that gave the armies control of transportation.42 Transportation Corps historians are inclined to agree. But they contend that an absolute

Table 13: Development of the QM Depot System on the Continent

(Thousands of Long Tons)

| Depot and Location | Required 1 Dec 44 | On Hand 13 Jan 45 | Capacity* 20 Jan 45 | Capacity* 30 Apr 45 | Required Jun–Jul 45 | Opening Dates | Mission. and Classes of Supply Handled |

| Q-171 Cherbourg | (b) | c 40 | (191) | (89) | d 0 | e 16 Jul 44 | Port depot; all classes until Q-181 took over Class II and IV |

| Q-172 UTAH Beach | (b) | c 10 | d (166) | — | — | f 8 Jun 44 | Base dump, all classes; reserve after Nov 44 |

| Q-173 OMAHA Beach | (b) | c 22 | d (22) | — | — | f 8 Jun 44 | Base dump, all classes; reserve after Nov 44 |

| Q-174 Rennes | (b) | c 15 | (79) | d (79) | — | f 6 Aug 44 | Staging area; Class I and coal |

| Q-175 Le Mans | (b) | (6) | (13) | d (13) | — | f 17 Aug 44 | Captured enemy materiel; CWS clothing |

| Q-177 Paris | (b) | c 41 | (47) | (91) | d 36 | f Oct 44 | Leave center; cold stores; PX and CA supplies |

| Q-178 Verdun | 99 | c 61 | (63) | (207) | 121 | e 1 Oct 44 | Class I and III for TUSA |

| f 25 Nov 44 | |||||||

| Q-179 Liege | 192 | c 27 | (102) | (235) | d 0 | e 1 Oct 44 | Class I and III for FUSA and NUSA |

| f 25 Nov 44 | |||||||

| Q-180 Reims | 123 | c 34 | (65) | (169) | d 0 | 123 Sep 44 | Class II and IV, northern armies |

| e Oct 44 | |||||||

| Q-181 Le Havre | (b) | c 12 | (15) | (116) | 100 | e 2 Oct 44 | Port depot; class II and IV |

| f 16 Oct 44 | |||||||

| Q-183 Charleroi | 80 | c 39 | (216) | (322) | 225 | f 15 Dec 44 | Overflow depot, class I, III, PX |

| Q-184 Luxembourg | 106 | — | (91) | — | — | e 10 Dec 44 | Never active (TUSA dump) |

| Q-185 Lille | — | — | (57) | (185) | d 0 | e 30 Dec 44 | Overflow depot, class II and IV |

| f 16 Jan 45 | |||||||

| Q-189 Antwerp | — | (b) | c 32 | (64) | 200 | f 2 Dec 44 | Port depot, all classes |

| e 25 Apr 45 | |||||||

| Q-191 Rouen | — | (b) | (b) | (6) | d 0 | f 15 Oct 44 | Port depot, all classes |

| e 30 Apr 45 | |||||||

| Q-186 Nancy | — | (85) | d 0 | e 9 Feb 45 | All classes for SUSA | ||

| Q-187 Dijon | (b) | c 18 | c 32 | d (146) | — | e 20 Nov 44 | Intermediate depot for SOLOC, all classes |

| Q-188 Marseille | 180 | — | c 120 | (388) | 112 | f 1 Sep 44 | Port depot, all classes |

| e 1 Oct 44 | |||||||

| Western Mil Dist | — | — | — | (26) | 171 | e 22 Jun 45 | Occupation forces main depot, all classes |

| Eastern Mil Dist | — | — | — | — | 203 | e 22 Jun 45 | Occupation forces main depot, all classes |

| Berlin | — | — | — | — | 34 | e 22 Jun 45 | Occupation forces retail depot, all classes |

| Bremen | — | — | — | — | 770 | e 22 Jun 45 | Port depot, all classes |

| TOTALS | — | — | — | (2221) | 1973 |

* Figures in parentheses represent total capacity.

a In each case includes retail support for local units.

b Data lacking, but depot known to be operating.

c Tonnage currently on hand, excluding Class III.

d Depots to be inactivated.

e Date of formal activation.

f Approximate date operational.

Source: QM Supply in ETO, I; GONAD History: Hist of QM Sec ADSEC.

shortage of transportation facilities, irrespective of how they were administered, contributed materially to this situation.43 Geography constituted an additional source of difficulty. Antwerp was in the extreme northeast corner of Allied territory in Europe, conveniently close to enemy-occupied territory. With land transportation facilities so scanty, it went against the grain to move supplies away from the front; yet the area between Antwerp and the combat zone was so constricted that such action was occasionally necessary. The major example was Lille (Q-185), an overflow depot located some fifty miles southwest of Antwerp. This Class II and IV depot was established in January 1945 to complement Q-183, the Class I and III depot which had begun to operate at Charleroi a month earlier. Dijon (Q-187) became an intermediate depot in February, when CONAD moved forward to Nancy.

But a major feature of the December plan was retained in planning the spring offensive—the current advance depots were to become the main intermediate depots as soon as the armies had moved forward. This aspect of the depot plan was sound and operated smoothly. Even in December it had been a good plan, and in retrospect General Somervell’s criticism of it does not seem completely justified. It is true that excessive stocks of Class I supplies had been concentrated in the forward areas, but these were unbalanced stocks that had accumulated because of poor transportation practices as the advance depots tried to achieve their assigned levels of balanced rations. Those levels were part of an Allied plan for offensive action, and in that context the excesses in the forward area were an asset rather than a liability. That they were also a tempting target was a minor consideration. In all military operations, an enemy “spoiling attack” against one’s own offensive preparations is a constant possibility, but the threat is a responsibility of tactical rather than logistical headquarters. It was not reasonable to demand that COMZ be more cautious than SHAEF in estimating enemy capabilities.

Base Depots

General Somervell’s criticism of port and base depot operations was entirely justified, although here, too, SHAEF must bear part of the blame. Two major ports, Le Havre and Antwerp, were in the British zone, and the British permitted use of them only under arrangements which COMZ considered ill-advised and hampering to its operations. The heart of the problem was the absolute necessity for a transit depot immediately adjacent to each major port, where supplies could be inventoried and stored at least temporarily. In the United Kingdom, this need had been met by sorting sheds, as already described. At Cherbourg, the advice of the ADSEC quartermaster was ignored since initially this was the only large port available. Under combat conditions Transportation Corps officers regarded segregation and inventory as unnecessary and time-consuming. Cargoes were dumped on the docks and segregated by technical service and class of supply only. Shipments inland were measured in tons rather than items. Selective loading was the exception

rather than the rule, and brooms, soft drinks, and fly swatters were sometimes shipped at a time when there was a crying need for winter clothing. Furthermore, supplies were unloaded from ships’ hatches directly into railroad cars and dispatched to interior depots without shipping documents. When the forward depots received equipment for which there was no immediate need at the same time that shortage of transportation prevented interdepot exchanges, it meant that valuable space was burdened with slow-moving stocks.44

In November, operations at Cherbourg were reorganized under the direction of Maj. Gen. Lucius B. Clay, but similar practices persisted at other ports into 1945. The beach depots at OMAHA and UTAH would shortly be closed by winter weather, and interior depots were needed to drain off the rapidly accumulating surpluses at Cherbourg. Despite the disadvantages involved, inland installations would have to serve as sorting points where, for example, forty million pounds of unbalanced B rations, many of them left behind by the First Army, could be converted into five million balanced rations and where items unnecessary for active combat could be segregated.45 For sized items of clothing, the solution was to concentrate all Class II operations at Reims. Other supplies could not be handled at any single depot, and the problem of efficient sorting and inventory remained unsolved until after V-E Day. (Chart 3)

In an effort to reduce the necessity for inventory, NYPE initiated commodity loading of ships. For example, all the ingredients for two million B rations, loaded on a single ship in New York in the correct proportions, could be shipped to a single port with a minimum of paper work. But a shipload made about sixteen trains, and if all these trains were not dispatched to the same destination the balance was destroyed, and the inland depot received food, but no balanced rations. Sized items of clothing presented the same problem. G-4’s tight control over trains frustrated the efforts of technical services to control items. When Littlejohn obtained small consignments of specific items from the United Kingdom to balance rations or clothing tariffs, he always asked for direct delivery by air. If this was impossible, such shipments were sent by small coaster to a specific port with an officer escort to insure that the supplies were not lost or diverted.46

Antwerp

As already noted, Antwerp was the great port on which all plans had hinged even before its capture in September. Since Antwerp was west of the inter-Allied administrative boundary, the Supreme Commander decided that it would be opened under British control, although slightly more than half the facilities were assigned to the Americans. The detailed technical agreement regarding operations was worked out by Maj. Gen. Miles H. Graham, Chief

Chart 3: Progress in Inventory of QM Supplies

Source: OTCOM TSFET Operational Study 5, p. 7.

Administrative Officer, 21st Army Group, and Col. Fenton S. Jacobs, Commanding Officer, Channel Base Section. It was obvious from the start that port clearance would be a major problem, and plans were made to use less than half of the tremendous port capacity (242 berths) . In peacetime, the Belgians had operated the port on a tight schedule with a minimum of delay and had provided only very limited local storage space. Military operations demanded far more flexibility, and by mid-December, when the 13th Major Port was unloading 19,000 tons per day of American cargo, the backlog was already troublesome. The G-4 plans officer had estimated that any accumulation of more than 15,000 tons would hamper operations, but 85,000 tons were already stacked under tarpaulins back of the quays and no relief was in sight. At the end of the month the British granted space for another 50,000 tons, but estimates were that this would be filled up by 19 January. The Battle of the Bulge was then at its height. COMZ had ordered an embargo on freight to Liège and Namur, which Littlejohn considered overtimid and ill-advised. Ultimately, alternate overflow depots were selected and organized at Charleroi (Q-183) and Lille (Q-185) . But meanwhile the performance of this great port had been most disappointing. During January the tonnage actually cleared in the American side of the port averaged less than 11,000 tons per day.47

Low-priority supplies at Antwerp awaiting rail transportation, January 1945.

Littlejohn was extremely critical of the “Treaty of Antwerp,” whereby the U.S. forces agreed not to establish a depot in that city, and contended that the congestion could not be corrected in any other way. The necessary space was already occupied by American supplies, which a depot organization could inventory and dispatch inland. But the British feared that this process would slow down the clearance of the port and constitute a precedent for formal and permanent admission of U.S. supply services into port areas. They refused for several months to permit establishment of a depot, but meanwhile General Somervell, during his visit to the theater in mid-January 1945, asked General Littlejohn to remedy the situation if possible. Thus assured of at least tacit approval, Littlejohn set up a completely unofficial branch of the Le Havre depot at Antwerp under Col. George L. Olander. On 2 March this branch was formally activated as Depot Q-189. On investigation, a major depot site within the city proved to be neither possible nor desirable. Depot Q-189 acquired 2,750,000 square feet of open storage along the Albert Canal outside Antwerp, which was used principally to store heavy tentage and similar low priority articles which had clogged the port. Thereafter, Q-189 operated primarily as a sorting

and inventory center, advising the port quartermaster on the desired disposition of QMC supplies, segregating low priority articles, and expediting critical items direct to the armies.48

While a transit depot at each major port was essential for orderly QM operations, proper coordination with the Quartermaster Section of the Port Headquarters was equally important. In a major port, this was a unit of seven officers and twenty-nine enlisted men. Littlejohn considered the port quartermasters the least satisfactory of the QM personnel in the ETO. They had been placed on detached service with the Transportation Corps before leaving the United States, and neither service had taken much pains with their selection or their training for these key assignments. The Transportation Corps manuals defined their duties quite correctly, but both port quartermasters and port commanders either ignored these instructions or failed to understand them. Most port quartermaster sections functioned merely as station supply or mess personnel, and did not participate in the port operation of accounting for and forwarding quartermaster supplies.

Despite the shortage of experienced officers in the OCQM, Littlejohn found it necessary to replace the senior port Quartermaster officers at Cherbourg, Rouen, and Antwerp. In the case of Antwerp, this action encountered active resistance from Col. Doswell Gullatt, Commanding Officer, 13th Major Port. Early in December Littlejohn had arranged informally with the chief of the ETO Transportation Service, General Ross, to replace the current Antwerp port quartermaster with Col. Edwin T. Bowden, an extremely well-qualified storage and distribution expert. Colonel Gullatt maintained that the transfer had not been processed through proper channels, and, moreover, that he was satisfied with his port quartermaster. He appealed to General Lee, who found that Generals Littlejohn and Ross were in agreement and decided in their favor.

The incident illustrates the significant fact that ports were units almost equal to base sections in importance, and equally inclined to resist personnel actions taken through technical service channels. Nevertheless, Littlejohn was able to establish that port quartermasters were “part of the QM team,” and thereafter included them on his distribution lists and in QMC conferences and inspections.49

Headquarters and Headquarters Company, QM Base Depot

The major role assigned to the Headquarters and Headquarters Company, QM Base Depot, in the Italian campaign has already been described.50 These were senior command

organizations, designed for the administration of widely dispersed activities. The official organization as originally authorized by the War Department was somewhat inflexible and not altogether in harmony with the ideas of ETO quartermasters, who had been experimenting along similar lines since 1943.51 Colonel Sharp, former Deputy CQM, ETO, drafted the first experimental T/O while serving in North Africa in August of that year. Unlike the official table, his proposed organization had provided for the elaborate storage and distribution functions necessary under overseas conditions of wide dispersion. Moreover, dispersion implies presence of a large local military population, requiring retail support and local services, which must also be provided by the base depot. In the ETO this military force included AAF as well as COMZ personnel, and sometimes such local responsibilities were one quarter or more of the total mission. The OCQM also found the official War Department table, with its 4 colonels and 8 lieutenant colonels out of a total of 36 officers, somewhat top-heavy from the standpoint of rank. This was extremely inconvenient if the senior officers assigned to the unit in the United States were lacking in field experience and had to be transferred. But despite these minor faults the organization filled an urgent need. It provided official recognition that a Quartermaster depot was a major activity requiring a large amount of specialized senior personnel, and Littlejohn wrote to The Quartermaster General early in 1945 that “this depot organization has undoubtedly proven one of the greatest assets developed for the Quartermaster Service.”52

With the tacit consent of the G-1 Section, the OCQM modified the organization and grade structure of each of these units to fit the particular mission of the installation to which it was attached. Thus, at Verdun, essentially a rations and POL depot, the Headquarters Company, 62nd Quartermaster Base Depot, elevated subsistence matters from a branch of the Supply Division to an independent Subsistence Division, and assigned more than a quarter of its officers to this operation. At Reims, on the other hand, the 55th Quartermaster Base Depot assigned less than one-seventh of its officers to subsistence activities while 21 officers concerned themselves with all phases of the Class II and IV mission. Had it not been for such flexibility, which Littlejohn felt had been too long absent from the QMC, it would have been impossible for a single unit such as the 62nd Headquarters and Headquarters Company to administer a “depot” like Verdun, which actually consisted of 41 subinstallations spread over a territory of 6,400 square miles. This depot complex contained nearly fourteen million square feet of storage space, and in addition to POL handled up to 450,000 long tons of freight in a single month. It controlled 39 Quartermaster companies of various sorts, and had a strength of 13,000, of whom less than half were U.S. personnel. Yet the 62nd QM Base Depot

itself numbered only 36 officers and 118 enlisted men.53

These units were used in the communications zone only. At advanced depots, one QM base depot plus one QM group was able to administer supply operations for a field army. In intermediate and base sections, their responsibilities were sometimes considerably greater, but more subunits were attached. Seventeen QM base depots served in the ETO, including one permanently attached to OCQM headquarters.54 (See Appendix B.)

Depot Facilities

The performance of base depots in the ETO was affected by conditions which apparently were not anticipated in the zone of interior training of Quartermaster troops and only partly foreseen in OVERLORD planning. The reports of base depots, from Cherbourg to Liège, refer again and again to shortages of closed and weatherproof storage space, weak or uneven floors that made it impossible to use fork-lift trucks, lack of other materials-handling equipment, poor lighting facilities, rutted roads, muddy or flooded fields, insufficient dunnage, bombed out rail trackage, and scarcity of rail equipment and of responsible civilian labor. Though their facilities were conspicuously inferior to those of the zone of interior, the inland installations were better than those at the original beachhead depots at Bouteville (Q-172) near UTAH and Le Molay (Q-173) near OMAHA, with their stocks piled in open fields, where hot weather melted lard and chocolate, and rain spoiled other stores. Here the shortage of truck transportation to railheads had been chronic, and occasionally horse and donkey carts carried stocks to rail sidings. Topography prevented real improvements at these sites, but for lack of better facilities the beaches continued to operate until mid-November. The storage areas were then turned over to Cherbourg (Q-171), which did not completely clear them until late March 1945.55

As the troops moved inland depots were located at leading rail centers. Wherever possible, warehouses and sheds in proximity to rail yards were converted to quartermaster uses, but too often such facilities had been Allied bombing targets. Now they suffered from leaking roofs, weak flooring, and exposure to pilferage, and usually had to be cleared of much debris. For these reasons the bulk of supplies at all depots in France were stored in the open in accordance with techniques developed in Great Britain. At Paris, Charleroi-Mons, Liège, and Verdun, tremendous quantities of quartermaster supplies were stacked in the freight yards. At Liège, eight million gallons of gasoline were lined along the Meuse River for two miles.

In the absence of concentrated facilities, every depot became a cluster of subdepots distributed around the various centers. The installations of the Charleroi-Mons Depot were dispersed

Open storage of flour at Verdun, December 1944.

over an area of 4,700 square miles, while Liège Depot controlled warehouses and open storage scattered across the entire width of Belgium from Herbesthal westward to Givet, France. Similarly, the 62nd Quartermaster Base Depot, sent into Verdun before the Third Army had evacuated that city, found that the most desirable storage sites had not been released by army units. It established eight Class I and eight Class III sub-depots using all rail sidings within a thirty-mile radius of Verdun. Usually, the exploitation of open space required the assistance of the Corps of Engineers. Areas had to be graded, rubble cleared, and road networks laid out. In addition, fences had to be constructed for security, lights for night work installed, and cranes set on concrete bases.56

Not all of a depot’s difficulties resulted from such physical handicaps. Allowance had to be made for the difficulties of adjusting to economic and topographical conditions on the Continent, all of which were aggravated by the pressure of combat. After several inspection tours through the depot system, the CQM set up short courses of instruction, notably at Reims, to give key personnel additional training in better supply and storage procedures. At UTAH Beach, a Quartermaster Orientation School conducted evening classes for transient Quartermaster officers, emphasizing the operation of continental depots and depot headquarters.57

Experience had convinced Littlejohn that technical training in an overseas theater had to be directly under the

supervision of each chief of service. The Quartermaster Section of the American School Center at Shrivenham had proved to be completely ineffective in solving the current problem—providing a large number of competent Quartermaster officers trained to perform specific tasks. When the QM School was transferred to the Continent late in 1944, he insisted that it be placed under his immediate control. Col. Henry A. Wingate commanded the school, first at the Isle St. Germain and later at Darmstadt, Germany. He was an experienced QM officer who had previously commanded various general depots in Great Britain and had been quartermaster of Northern Ireland Base Section and Loire Base Section. Wingate kept the curriculum of the school flexible to meet the changing needs for various types of QM specialists. He insisted upon a practical approach to current problems, and endeavored to provide instruction in up-to-date solutions and techniques. Lectures by outstanding experts in various QM specialties were a notable contribution to that end. Such men invariably held key positions from which they could be spared but very briefly. They were made available primarily because the school, like the installations to which they were assigned, was a part of the Quartermaster Service, so that cumbersome staff liaison was not needed to secure their services.58

The United Kingdom Base

With the development of the COMZ on the Continent and the influx of men and matériel into France directly from the zone of interior, the United Kingdom, once the center of activities in the European theater, was relegated to the role of a base section somewhat isolated from the main axis of supply. The eleven months of the major campaign against Germany saw Britain, which, according to the contemporary jest, had been sinking under the load of Yankee supplies, start on its way back to normal conditions. But manifold problems still confronted Quartermaster personnel remaining in the United Kingdom.

The RHUMBA plan provided not only for the transfer of base sections to the Continent but also for progressive inactivation of supply depots and reduction of stocks in the United Kingdom. Installations were to be either closed down completely or returned to the British. Depots and maintenance, reclamation, and salvage facilities were to be consolidated in order to conserve military manpower.

During 1944 the Eastern, Western, and Southern Base Sections became districts under the single United Kingdom Base, and Northern Ireland Base Section was inactivated and absorbed by Western Base Section, later Western District. In April 1945 all the districts were disbanded and their responsibilities transferred to the various depots. In the “Little America” (Grosvenor Square) section of London, Central District served both the U.K. Base headquarters and COMZ Rear. The Quartermaster officer here represented the Chief Quartermaster in miscellaneous functions, which included operation of the London Sales Store, the London Baggage Bureau,

and the outlying Brookwood Cemetery. The U.K. Base quartermaster also cooperated with Special Services and the Red Cross to provide services for combat troops on leave from the Continent.59

Depot Closing Program

RHUMBA was barely two months old when Col. Aloysius M. Brumbaugh, the quartermaster of U.K. Base, informed General Littlejohn that the scheduled closing dates for the depots could not possibly be met and that perhaps as much as a ninety-day delay was unavoidable.60 The most serious problem was Transportation Corps’ inability to furnish shipping for the movement of stocks to the Continent. Backlogs at closed installations and in open depots, including civil affairs supplies, totaled 131,000 long tons. These had to be moved before the closing program could be carried out. Meanwhile the inactivation of depots was delayed by an order from U.K. Base headquarters prohibiting interdepot shipments except to balance inventories. Under these circumstances, the close-out of Quartermaster Sections at general depots was postponed thirty days, but any prospective relief was almost immediately offset by the sudden and unanticipated diversion of four divisions and 17,000 nondivisional troops to the United Kingdom.61

By the end of November, 9 of the original 18 general depots had suspended operations and a month later only 4 of the 11 original QM branch depots were still open.62 But the general depots were not closing fast enough to suit the OCQM. Pointing to the lengthening lines of communication and the imminent entry of American forces into enemy territory, Littlejohn reiterated the urgent need for Quartermaster personnel on the Continent. To hasten the closeout program, he urged that the directives against interdepot shipments be modified and that surveys be inaugurated to determine what stocks could be transported to the Continent, what ought to be shipped back to the United States or to other theaters, and what could be disposed of locally in Britain.63

Base of Supply

Meanwhile U.K. Base served as a supply base for the forces on the Continent, particularly for fresh fruits and vegetables and for Class II items. But in the realization of this mission the theater-wide shortage of transportation was a severe handicap. The crux of the problem was securing an adequate allocation of cross-Channel shipping for quartermaster items. When the U.K. Base quartermaster’s tonnage allocation for September 1944 was set at 62,000 long tons, the OCQM pointed out that it

needed 88,000 long tons. It predicted that this shortage would hurt the winter clothing program. Moreover, it complained of delays and pilferage of critical supplies, and requested permission to overcome this handicap by the use of airlift. This request was denied, for at the moment POL was the most critical item on the Continent. The Red Ball express was operating at full capacity and all available airlift was being used to move the fuels continually demanded by the armies.64

In October the Quartermaster tonnage allocation for shipments out of the United Kingdom was increased 50 percent, to 92,000 long tons, but even this figure was only half what had been promised. Fortunately, the stabilized tactical situation had reduced POL requirements, and winter clothing and equipment began to enjoy higher transportation priorities.65 By this time, the need for winter clothing and equipage had become so critical that the OCQM authorized U.K. stocks of such items to be reduced to zero, and it even directed that service and AAF units in Great Britain turn in overcoats and arctics for the use of front-line troops. By November, U.K. Quartermaster depots were actually having trouble finding the supplies to fill allocated tonnages.66

During the last six months of 1944, Colonel Brumbaugh ran into personnel and labor problems similar to those of his colleagues on the Continent. Shortages of military and civilian workers resulted in poor warehousing, inaccurate inventory records, and a laxity growing out of the realization that the job could not be properly accomplished. His own office was subjected to repeated drafts by OCQM, beginning with instructions on 19 August to reduce his overhead to 68 officers and 225 enlisted men by September.67

But these personnel problems were not merely quantitative. Having added German POW’s and Italian service units to the British civilians and Irish “industrials” hired before D-day, the Quartermaster Corps found itself with a labor force of mixed and conflicting national loyalties. Moreover, the Continent was calling for the transfer of all Italian service unit troops, numbering nearly seven thousand, and offering only three thousand German prisoners as replacements.68 Luckily, these multiple pressures on the U.K. Base quartermaster were alleviated by measures to get more British workers, by delaying the departure of the Italian service units, and by the action of the Commanding General, U.K. Base, in prohibiting the transfer of personnel to the Continent if such a shift endangered the local mission. The

increasing autonomy of the U.K. Base was demonstrated in December, when Colonel Brumbaugh began to prepare independent requisitions on PEMBARK.69

By the first anniversary of U.K. Base, Quartermaster activities had decelerated, keeping pace with the base as a whole. Incoming QM supplies from the United States during August 1945 dropped to a mere forty-five tons, the lowest in the three years of American military activity in the United Kingdom. This virtual termination of receipts led to notable decreases in interdepot shipments; the outloading of quartermaster supplies continued, but on a very modest scale. Local procurement was drastically cut, and salvage installations either closed down or were turned over to organizations scheduled to retain a permanent location in Great Britain.

On so April 1945 (the nearest month-end to V-E Day), there were 431,860 American troops in the U.K. Base, and U.S. supplies still exceeded 1,000,000 tons, including many items no longer needed on the Continent. Cross-Channel shipments had reached 392,000 tons in April, but dropped to 150,000 tons in June. Shortly after V-E Day, embargoes on shipping both into and out of Great Britain were applied to all supplies not needed for redeployment or for civil affairs purposes.70

Quartermaster Support During the Battle of the Bulge

On 16 December, the combined British, Canadian, American, and French forces stood generally along the German border, although the First Army had captured Aachen and the Germans held out in Colmar. Military leaders had decided to resume the offensive toward the Rhine by attacking in the direction of the Roer dams on the north and the Saar on the south. In deploying his forces to bolster this double threat, Bradley directed Hodges to reduce his strength along the eighty-mile Ardennes front to four divisions. Rather than assume a defensive winter position, the high command took a calculated risk and determined to renew the offensive toward the enemy’s homeland.71 The organization of the supply system for close support of this advance had been completed during November. COMZ had built up stocks in Liège (Q-179) for the First and Ninth Armies and in Verdun (Q-178) for the Third Army. Army depots were equally well prepared. But when the enemy’s panzer divisions struck in force through the Ardennes, hoping to capture or destroy the large stocks which the Americans had concentrated in the forward areas for their own projected offensive, these supplies had to be rapidly evacuated.

On 20 December SHAEF, having noted how the German thrust disrupted lateral communications, extended Third Army’s left boundary northward to the line Givet—St. Vith and transferred the battered remnants of VIII Corps from