Chapter 16: Clothing for the ETO Enlisted Man

Clothing and Individual Equipment

Comprising some 50,000 different items, clothing and equipment (Class II and IV) was the most complicated category of Quartermaster supply. The combat troops only needed such supplies intermittently, and in quantities far smaller than their steady requirements for rations and gasoline.1 But when the need for Class II and IV items arose it was usually immediate and urgent, and required complicated procedures for requisitioning, inventory, distribution, and tariff balancing that were not encountered in dealing with other QM supplies. Except for combat losses, clothing and equipment were regarded as nonexpendable, and troops received a complete new combat-type outfit at the beginning of a campaign. Apart from unexpected tactical developments or drastic changes in the weather, it was assumed that this initial issue would be sufficient for a predictable length of time, during which commanders and senior logistical staff officers expected to ignore the minor shortages that might arise and concentrate on their more essential daily requirements. Consequently the transportation priority assigned to clothing and equipment was kept low until shortages became rather serious, and then was raised to overcome them.

Possibly because of the relatively small tonnages involved, there was a tendency at higher staff levels to minimize the importance of clothing and equipment and an urge to handle this category of supply on the same daily tonnage basis that was successfully applied to rations, gasoline, and ammunition. This was a major error. Needs for clothing and equipment were invariably for specific items and sizes, and not for bulk tonnage. Even at army level there was hardly such a thing as an average daily requirement for Class II and IV supply. The tactical units had understood this from the first, and normally drew such supplies direct from an army depot on a weekly or ten-day basis against a requisition submitted in advance.2

Gradually the armies also came to realize that only a large specialized depot, with ample stocks of all Class II and IV supplies to support several armies, could meet these specific

demands. Except for certain standard fast-moving items, an attempt to meet anticipated requirements by building up stocks at army level depots was not successful. After repeated moves by the depots, sizes were no longer properly balanced and inventories were no longer accurate. Stocks tended to become what was surplus to the needs of the particular army being supplied, although the same items might be desperately needed by another army.

The Class II and IV depot at Reims, later designated to serve all the armies in northern France, was formally activated on 23 September 1944 by the 55th QM Base Depot, and played a major role in the initial issue of winter clothing to the troops. Although transportation was very scarce the mechanics of initial issue were simple, and at first Reims operated more as a reconsignment point than as a real depot. Littlejohn had noted the advantages of this site on a major lateral rail line, and it passed to his direct control on 25 October. But another six weeks elapsed before the depot had sufficient balanced stocks to operate efficiently and promptly fill the specific requisitions of the armies. Those stocks were accumulated by mutual agreement of COMZ and 12th Army Group, despite the fact that SHAEF had allocated all tonnages for such supplies directly to the armies.3

The QM Class II Plan for OVERLORD

For reasons of mobility, the assault troops landing on the Normandy beaches brought ashore a minimum of clothing and equipment.4 All troops involved in the initial attack had turned in their winter clothing before leaving the United Kingdom. Moreover, the combat units in the assault also gave up everything not absolutely essential. The only replacement clothing they carried was three pairs of socks per man. Apart from impregnated herringbone twill fatigues, worn primarily as protection against gas warfare but also for warmth and to shed rain, the ETO summer uniform was all wool. For winter, heavier items would be added, but summer items would not be turned in. During the first six weeks of combat, so-called beach maintenance sets were issued to division-sized units every five days. Each set would replace items of the assault outfit lost or destroyed during combat. This system of replacement was most successful, probably because the sets were not intended to augment the meager initial allowances but only to maintain them temporarily. Within those limitations, the sets obviated the usual complicated Class II and IV supply procedures in the forward areas. Replacement was simplified by denying the troops many items normally supplied even during active operations. For tactical units fighting in mild weather the policy was entirely satisfactory.5

Clothing Issues in Mild Weather

For the first month on the Continent, units were supplied direct from the beach dumps. The tarpaulin-covered boxes of the original skidloaded beach

Issuing items from beach maintenance sets at the Normandy beachhead near Longueville, July 1944.

maintenance sets proved useful for open storage of other clothing. Cherbourg, which was destined to become the main depot for the area, absorbing the OMAHA and UTAH dumps, was transferred from First Army to ADSEC control on 16 July. The previous day Littlejohn had assigned the future depot the mission of holding a 60-day level of Class II and IV supply for 385,000 men. By the end of July ADSEC reported that 45,000 long tons of QM Class II and IV supply had arrived on the Continent since D-day, but OCQM observers reported that many useless “filler” items had been included, and that pilferage and careless open storage had diminished the value of the stock.6

Littlejohn’s depot plan was a first step toward a more orderly system of supply, but before the system could be put into full operation the troops had broken out

of the beachhead and the pursuit phase of the campaign had begun. During early August some 600 tons of clothing and equipment were issued to Third Army from a dump at St. Jacques de Nehou, and about 800 tons to First Army from the dump at St. Lô. During the following period of daily tonnage rationing and rigid allocations, gasoline and rations were the important items, and clothing received low priorities. In practice, this meant that when available transportation was less than the allocation, Class II and IV supplies suffered. This applied equally to cross-Channel, rail, and highway tonnage allocations.

By early September the pursuit had ended and army quartermasters had time to take stock of their accumulated shortages, many of them dating back to the period of hedgerow fighting in Normandy. It seemed clear that the troops had lost or abandoned more equipment than had been worn out or used up, but large-scale salvage activities in France were just beginning, and the effectiveness of salvage for replacing inventories was still a matter of conjecture. Prudence demanded that all shortages be covered by requisitions for new items and that the continental depots be permitted to accumulate clothing reserves up to the theater’s authorized sixty-day level. On that basis, continental requirements were enormous—about two and a half times the War Department estimate. However, summer was over, and delivery of winter uniforms and equipment to the troops took precedence over replacement of articles lost or worn out since D-day. On 7 September Busch wrote to Littlejohn, “It is getting cold up here. The troops will need heavy clothing very soon. ...” The fact that “up here” meant somewhere east of Verdun, nearly 400 miles from the only available ports, certainly complicated the problem. In addition, unit quartermasters were somewhat puzzled as to what the winter combat uniform actually would be.7

The Winter Uniform for the European Campaign

Combat operations in winter—a comparatively recent development in war-fare—are only possible if troops are properly clothed. As late as World War I, activity diminished in cold weather, and trench-type warfare gave the troops opportunities for shelter that did not exist in the World War II war of movement. Quartermasters in Great Britain reviewed combat experience with winter clothing in North Africa and Italy in 1942 and 1943 and decided that it was not applicable in all respects to the forthcoming ETO campaign. Meanwhile, American troops stationed in the United Kingdom conducted maneuvers in England’s very different climate. They were leading a garrison life in a friendly country where troop discipline was of great importance to international relations, and their commanders were convinced that a smart appearance was vital to discipline. The service uniform was worn in most headquarters and by all personnel after duty hours. Limited dry cleaning facilities in Great Britain made it difficult to keep the serge service coat presentable, and light shade olive

drab trousers quickly showed the dirt. Soldiers who had obtained passes were sometimes unable to go on leave because they could not pass inspection, which naturally created a morale problem.

The inadequacy of these garments as a combat uniform had already been demonstrated in North Africa. The solution adopted by officers in both theaters—to wear dark green trousers instead of “pinks”—pointed out the need for a similar darker shade for enlisted men. The olive drab field, or Parsons, jacket, issued since 1941 was also unsatisfactory. It required frequent washing, was hard to iron, and scrubbing soon frayed the collar and cuffs. Quartermasters in North Africa and Great Britain and OQMG observers sent to both theaters all agreed that a new and improved uniform was needed—warmer, more durable, and better looking than the 1941 Parsons jacket, but less constricting and requiring less care than the serge service coat and light shade olive drab trousers. If such a uniform could improve the shabby appearance of combat soldiers, who had the greatest need for recreation and the least opportunity, it would solve many difficult combat zone problems involving the often conflicting demands of discipline and morale. But there were wide differences of opinion as to just how these desirable characteristics were to be achieved. Varying emphasis on comfort, warmth, water repellency, and a smart military appearance could and did result in a wide variety of designs and proposals.8

The ETO Concept—The Wool Jacket

Very soon after his arrival in the theater, Littlejohn, whose previous assignment had been as chief of the OQMG Clothing and Equipage Division, became interested in the battle-dress outfit, which constituted the British solution to the twin problems of smart military appearance and combat utility. This consisted of a short bloused jacket, snug-fitting at the waist, and easy-fitting trousers. The trousers were very high-waisted, so that the short jacket provided an adequate overlap but did not constrict body movement. With its belt at the natural waistline the jacket did not “ride up,” even during the most vigorous exercise, and presented a trim military appearance. The outfit called to mind the field uniform worn by U.S. troops during the Mexican War9 and reflected normal British civilian tailoring of trousers and waistcoat, but was contrary to current American civilian styling and military design, which tended toward a tight-fitting, low-cut trouser supported just over the hipbones by a belt. Another typically British feature of the battle dress was the rough, heavy texture of wool fabric, which made it possible to clean the uniform by scrubbing or brushing, and which did not require pressing. The jacket was lined with a heavy shrink-resistant cotton drill,

Field Marshal Montgomery wearing the British battle dress uniform on an official visit. June 1945.

and could be worn with or without undergarments. Such clothing was entirely suitable to the raw but not very cold climate of the British Isles, and could absorb moisture without making the soldier feel damp. Additional advantages were that the battle dress fabric could be impregnated with antigas chemicals for wear in combat, and could be dry cleaned for garrison wear. It could be passed through this cleaning and re-impregnation cycle repeatedly without shrinkage or injury to the cloth. Moreover, the British had available surplus chemicals and impregnating facilities.10

Early in 1942 a few battle dress uniforms were issued U.S. troops to make up for clothing shortages of arriving Americans. They were very popular, and the senior commanders in the theater unanimously approved Littlejohn’s suggestion that a generally similar uniform, made of the same material but cut to a distinctively American design, would be ideal for U.S. troops in garrison in the British Isles, as well as later in combat. It would replace not only the serge service coat and the current type of field jacket but also the protective impregnated wool shirt and trousers which had been very unpopular with garrison troops in the United Kingdom.11 The initial ETO request to purchase 5,000 uniforms was not approved by clothing specialists in the OQMG Research and Development Branch. By mid-1942 special uniforms for the Alaska garrison and for armored, parachute, mountain, and amphibious troops had all been developed. Littlejohn’s ETO project seemed to the R&D men to be just one more “special development” at a time when OQMG efforts had shifted toward devising a more versatile and generally applicable winter combat uniform. But on 5 October 1942 General Somervell of ASF had personally approved a purchase for test purposes and possible future development.12 Later in

ETO jackets as worn by generals Eisenhower and Bradley. General Bradley’s jacket is an early experimental version designed and made in England.

the same month General Lee recommended to the theater commander that 360,000 wool jackets of the new design, enough for all ground and service personnel then in the theater, be purchased locally. On 2 December General Eisenhower authorized a purchase of 300,000, but because of repeated changes in design only 1,000 jackets for test purposes finally became available on to May 1943.13

Five days earlier a theater circular had settled the matter of protective clothing by directing that impregnated herringbone twills—in other words the fatigue clothing already in the hands of the troops—would be worn for that purpose. Far from dampening interest in the new type of uniforms, this policy decision actually increased it. In Britain’s raw climate, fatigues were normally worn over wool clothing, and impregnation would make them more water-repellent. Members of the 29th Division, the only combat division in England not sent to North Africa for TORCH, had suggested such a combination to an OQMG observer in March 1943, and it was McNamara’s final choice for D-day. Scheduled tests of the jacket and matching wool trousers by units of the Eighth Air Force and the 29th Division were completed in July 1943, and both the troops and their commanders were enthusiastic. Even before the tests were completed Littlejohn wrote to Gregory, pointing out the superiority of the ETO wool jacket over the 1941 olive drab field jacket, the mountain and arctic jackets, and even the popular winter combat jacket of the armored forces. He suggested that the ETO jacket be manufactured in substantial quantities. In a separate letter five days later he pointed out the merits of a more loosely fitted wool trouser with larger pockets and a higher waist rise.14

As a result of the field tests, the participating troops suggested extensive changes in the jacket. For example, the slash pockets should be replaced by patch pockets higher on the chest, so that they would be accessible above the straps of the field pack. Since this was no longer to be a protective garment,

the protective flap at the front and the tight closure at the cuff should be eliminated. Littlejohn described the revised jacket in a letter to Gregory dated 21 July 1943, and sent samples. General Lee was also enthusiastic and in September urged that the new uniform be issued to all ETO troops.15

Meanwhile, The Quartermaster General had been requested to develop a similar wool jacket in the United States, first for the Air Transport Command arid later for all AAF personnel. In July the ETO commander, General Devers, decided that local production of jackets in the United Kingdom should be stopped until War Department policy had been clarified, and in November all the jackets on hand were turned over to the Eighth and Ninth Air Forces, which were actually in combat and needed them.16 Shortly after Eisenhower returned to the European theater as Supreme Commander in January 1944, Littlejohn reopened the question, recommending that the ETO type of wool jacket be issued to all ETO troops. Issue of this simple, multipurpose garment would effect a very great saving of money, materials, and labor. Only 300,000 jackets could be produced in the British Isles, and the balance required for 1944—3,115,000—would have to be manufactured in the United States.17

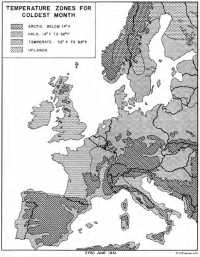

On 16 February the OQMG version of the wool jacket was shown to the ETO staff by Capt. William F. Pounder, whose activities as a QM observer in North Africa have already been described. The ETO staff found encouragement in the fact that the OQMG was also interested in developing a wool jacket, but noted wide differences between the OQMG and ETO versions that might lead to complications of supply. Moreover, the current official status of any wool jacket, irrespective of design, in the Army Supply Program was not very encouraging. If approved at all, it would probably replace the pile jacket authorized in December 1943 for wear in cold-temperate climates. Presumably this meant that the wool jacket would not be authorized for the mild-temperate climate of central and western France, where the U.S. forces expected to be fighting during the winter of 1944–45.18 (Map 3)

One month later, on 14 March, Littlejohn suddenly received a personal letter from Maj. Gen. Russell L. Maxwell, the G-4, War Department, which placed the

Map 3: Temperature Zones for Coldest Month

status of wool jackets in general in a different and far more hopeful light:

The Quartermaster General is studying the issue to your theater alone of the ETO field jacket. The only questions seem to be whether cloth is available in the United States, and whether machines are available. ... The QMG has estimated your needs to be 4,000,000 for the first year and your production to be zero. The chances for adoption will be improved if you can put into official channels your UK production prospects and your requirements from the United States.

The next day Littlejohn forwarded the above quotation to Col. James H. Stratton, the ETOUSA G-4, with the notation: “This information is somewhat like a bolt out of the blue. It is at variance with all information so far received on this subject.”19 In the light of this development, which seemed to indicate that some kind of a wool jacket was to be authorized in the ETO very shortly, a meeting with OQMG designers to work out a compromise design was clearly necessary. Since Somervell had summoned the chiefs of ETO technical services to a final preinvasion conference in Washington within the next few days, Littlejohn prepared to take care of the jacket matter personally. In accordance with Maxwell’s suggestion, Generals Eisenhower and Lee cabled the War Department on 17 March, recommending that the ETO type of field jacket be adopted for all ETO troops. Revised requirements were 4,259,000 jackets, of which 300,000 would be produced by the British. Littlejohn departed for the United States two days later.20

In a series of conferences during April 1944, Littlejohn and his clothing specialist, Maj. Robert L. Cohen, met in Washington with Maj. Gen. Lucius D. Clay of ASF, Colonel Doriot of the Military Planning Division, OQMG, Mr. Meyer Kestnbaum (president of Hart, Schaffner, and Marx), currently OQMG clothing adviser, and several others. Littlejohn obtained a firm commitment from Clay on his desired production program, but had to forego several desirable features of the garment as originally conceived. The rough, heavy, cloth used in the ETO version of the jacket was declared to be unobtainable in the United States. This was a major disappointment. As General Bradley had remarked, it was the British wool material that made it possible for one garment to serve as both a battle and a dress uniform.21 Nevertheless, it was agreed that the eighteen-ounce serge currently used for the enlisted man’s service coat would be substituted. It was likewise agreed that the biswing back and half-belt of the ETO model could be eliminated without decreasing its utility. But the elaborate details of the U.S. model, including pleated pockets, fly front closure and fly pocket flaps, and adjustable sleeve cuffs were all retained. During subsequent conferences attended only by technicians, Major Cohen insisted that the jacket be sized large enough to fit over

other garments of a winter uniform, but other details of design were decided by civilian consultants of the OQMG. After ASF had accepted the compromise design, Cohen wrote rather dubiously to Littlejohn that “... this garment will in all probability serve the purpose and is the best substitute we can get out of the Research and Development Branch.” Rather less charitably, the historian of the Philadelphia QM Depot, which had to shoulder the procurement problem, remarked: “In their determination to create a stylish as well as a utilitarian jacket, they brought forth a highly tailored one that proved to be the utter despair of manufacturers.”22

Later developments demonstrated that this decision regarding design did not arise from ignorance of mass production methods. Apparently the intent of the OQMG to create work for men’s dress-clothing manufacturers, a specialized segment of the garment industry that had not received any large government contracts up to this time, was carried out with excessive enthusiasm. Thus a principal reason for emphasis on style was a desire to tap a previously unexploited source of production capacity. Such a policy—if it actually was a deliberate policy—clearly involved increased costs. Its only justification was the possibility of a production bottleneck among the manufacturers already under contract, as hinted at by General Maxwel1.23

Fear of such difficulties was confirmed when General Clay cabled General Lee on zo April that only 2,600,000 wool jackets could be shipped to the ETO by the end of 1944, starting with 500,000 in September. He further stated that the wool jacket was officially replacing the serge service coat, which would not be furnished to the ETO thereafter. This was a logical compromise, involving a minimum disruption of the Army Supply Program, since both items were made from an identical wool cloth and overseas experience had demonstrated that the coat was superfluous. But Clay also made it plain that functionally the wool jacket was replacing the 1941 olive drab field jacket. Since the wool jacket allocation was short of requirements by more than a million and would arrive late in the year, he offered 479,000 old style field jackets as substitutes.

Littlejohn was disappointed by the curtailed allocation, and somewhat worried by the retarded schedule of deliveries. He considered this reduced ASF commitment barely adequate for the winter needs of combat troops and replacements, with nothing left over for service troops or for maintenance. He nevertheless accepted the substitution of 1941 olive drab field jackets and requisitioned all that were available.24

Most of the other clothing items required for winter were familiar garments issued in previous years. They were either on hand in depots, in possession of the troops, or would be brought overseas as individual clothing by additional units arriving in the theater.25

The OQMG Winter Uniform

Clothing specialists within the Office of The Quartermaster General were not really interested in any form of wool jacket. They had very different ideas on a suitable winter uniform for combat troops, and the first combat zone test of those ideas, involving the layering principle, had been made in North Africa in March 1943. A more extensive test of the same uniform was being conducted at Anzio as Littlejohn arrived in the United States.26 He had seen the experimental M1943 assembly in November of the previous year in Washington. Col. Georges F. Doriot of the Military Planning Division, OQMG,27 urged that the M1943 was the ideal winter outfit for combat troops anywhere in the projected area of operations, although at the time these garments were not officially accepted, and current plans were to authorize them only for arctic and cold-temperate climates and as replacements for the special winter combat uniform of tank personnel. Littlejohn disagreed. In his opinion Doriot’s experimental M1943 outfit, comprising successive layers of separate garments to be put on or taken off as the weather changed, would aggravate Class II distribution problems and was hopelessly complicated and inefficient for dismounted combat troops in a war of movement.28

In July 1943, the Quartermaster Board had reported that the M1943 combat outfit was unsatisfactory as an all-purpose universal unit, but recommended that the individual items be considered separately for suitability. In September, ASF approved an experimental procurement of 200,000 sets, to be tested by troops in training in the northern United States. Apparently these tests led to conclusions that the M1943 jacket should replace the old olive drab field jacket, and that the entire M1943 outfit was suitable for cold-temperate climates.

On 15 December 1943, as already described in connection with the outfitting of Mediterranean troops, the War Department issued a new table of clothing

and individual equipment embodying new concepts and listing a considerable number of new items. The M1943 clothing and a variety of garments previously issued only to mountain divisions, or for duty in arctic regions, might now be authorized by a theater commander on a discretionary basis for all personnel located in cold-temperate, alpine, and low-mountain terrain. He might also authorize additional and still more specialized items for specified percentages of his combat personnel in the same areas. Supply officers were warned that many of the new articles were in process of procurement or distribution, and stocks of substitute items would have to be used up first. In the revised table, the geographic basis of these authorizations within the continental United States was very clearly specified. Overseas, there was no such clear definition. Subject to War Department approval, theater commanders were in effect empowered to authorize the new articles for issue anywhere in the temperate zone. NATOUSA adopted a liberal interpretation of this table after the Anzio tests, generating requirements that the War Department approved only after some hesitation. But at the beginning of 1944 that decision had not yet been made, and interest centered on the reaction of the ETO, numerically the largest overseas theater.29

The new table was undoubtedly a disappointment to the OQMG Research and Development Branch since it did not prescribe the M1943 ensemble on a mandatory basis for the entire temperate zone, and plans were made immediately to bring about a change in that direction. A major requisition for the M1943 outfit from the ETO would go far to justify such a modification. It would also require a drastic revision of the Army Supply Program, since procurement up to that time was only for 200,000 men in training in the northern United States.

It was in support of plans to revise the clothing table, sponsored jointly by Colonel Doriot and AGF officials, that Captain Pounder was sent to the ETO in February 1944 with samples of the new items. The timing of this effort in salesmanship was not very propitious. Current plans set D-day in Normandy for 1 May, and preparations for the greatest amphibious assault in history were at fever pitch. Delays in operational planning had forced delays in logistical planning, which was now being completed within ADSEC and COMZ headquarters. Everyone’s mental horizon was limited to the crucial assault phase of the operation, and Pounder observed that “there seem to be no plans being made for another winter of war.”30

This was not quite correct. It would have been more accurate to say that clothing plans for the coming winter had been

completed and set to one side, and that everyone was too preoccupied with immediate problems even to consider revising them at the moment. Those plans were based on the official SHAEF forecast of post-OVERLORD operations, which was, of course, grossly in error. It indicated that the Allied armies would not reach the Ardennes and Vosges Mountains, where special clothing for wet-cold and low-mountain terrain would be required, until May 1945. For winter combat in western and central France, Littlejohn and his staff considered the type of winter clothing on hand entirely adequate. The fact that it was on hand in ample quantities, was extremely important, for as D-day approached the chronic shipping shortages of the ETO mounted to a crisis.31 Because of its preshipment program in 1943, the OCQM was in the most favorable supply position of any technical service, but for that very reason had large reserves of clothing, including limited-standard and substitute items, to use up before it could justify new requisitions. Littlejohn considered some of these “obsolescent” items—notably the armored force winter combat jacket and trousers—actually superior to the new designs. He favored some, but by no means all, of the garments now under consideration, and was determined to resist pressure to approve of new items merely because they were new. He had approved the M1943 issues for parachute units, but feared a chaotic situation if all combat units demanded similar garments. Accordingly, Littlejohn told Pounder that he was not to announce his mission or display his wares to anyone but QM clothing experts and military planners. If his samples were given too wide a display, he might oversell his product and create demands that could not be filled. This order was, of course, diametrically opposed to the views of Colonel Doriot, and largely frustrated the latter’s objective in sending Pounder to the ETO.32

Pounder himself either caught the fever of immediacy, or accepted the frame of reference of the officers, all senior to himself, with whom he was dealing. For example, he suggested to Colonel McNamara that the men in the assault might wear shoepacs. The First Army quartermaster pointed out to him that the wet French spring would soon be over, and then the shoepacs, which wore out quickly and in any case were

unsuitable for marching, would have to be replaced with shoes. This was considered an unwise use of precious cargo space. McNamara was interested in the wool sleeping bag to replace the blanket rolls planned for his assault troops. It would save weight and also make a more secure container for other items of clothing, but he seriously doubted that delivery could be made in time. In general, this was the prevailing reaction to all the samples presented by Captain Pounder. Most of the items he had to offer were currently being produced on a very limited basis. His purpose in coming to the ETO had been to invite requisitions to serve as a basis for future procurement, but his “customers” were interested only in emergency requisitions for stocks actually available. Pounder reported to Doriot that a requisition for ponchos was under consideration, and all available stocks of the new wool field trousers were requested for immediate shipment, but in both cases the quantities involved were small. As he himself expressed it, “plans have been pretty well formulated already and there is a good deal of hesitancy to change them. This is especially true of items of the basic uniform. It is essential that all troops have basically the same uniform. To change would require a huge number of new items to be shipped and cause considerable commotion. ...”33 As these words were written, the revised D-day was exactly twelve weeks away.

One major new item, the M1943 jacket, had already been authorized for all theaters, but Pounder brought the first samples seen in the ETO, and the initial reaction to the garment was also in terms of possible emergency requisition. Pounder apparently ascribed to Littlejohn the enthusiasm that some of his staff displayed for this item, stating, “The combination of Jacket Field M1943 over the ETO Jacket fits into the ETO plans and General Littlejohn is anxious to have it here in sufficient time to dress units uniformly.”34 While Littlejohn favored uniformity to avoid further complication of the already intricate Class II supply plans, there is no confirmation in other evidence that he expressed any desire for the M1943 jacket. Pounder had apparently expressed Littlejohn’s sentiments far more accurately in an earlier letter to Doriot, writing that the CQM and his staff were “convinced that their jacket ETO is superior [to the Jacket M1943] for this particular theater, and they are presently seeking the permission of General Eisenhower for authorization. Until this jacket ETO is definitely approved or rejected, nothing will be done to change present conditions of the supply of Jackets M-1943.”35 The “present conditions” referred to were the directive in T/E 21 that the M1943 jacket was only to be issued after stocks of the 1941 style jacket were exhausted. As already noted, Eisenhower made his formal decision in favor of the ETO jacket on 17 March. Apparently his choice was based upon the relative desirability of the two jackets, without regard for the

possible role of the M1943 as part of an outfit to serve as a substitute for the overcoat. It is likely that the sloppy loose fit of the M1943 had a strong bearing on his final decision. A year earlier, when he wrote to General Marshall regarding the somewhat similar Parsons jacket, he already had positive ideas on what should replace it:

I have no doubt that you have been impressed by the virtual impossibility of appearing neat and snappy in our field uniform. Given a uniform which tends to look a bit tough, and the natural proclivities of the American soldier quickly create a general impression of a disorderly mob. From this standpoint alone, the matter is bad enough; but a worse effect is the inevitable result upon general discipline. This matter of discipline is not only the most important of our internal military problems, it is the most difficult. In support of all other applicable methods for the development of satisfactory discipline, we should have a neater and smarter looking field uniform. I suggest that the Quartermaster begin now serious work to design a better woolen uniform for next winter’s wear. In my opinion the material should be very rough wool. ...”36

Littlejohn’s opinions were similar. He recalls that the first M1943 jackets he ever saw actually being worn by troops clothed a WAC unit he watched debarking early in 1944. The remarks inspired by their appearance were unprintable, but the Wacs’ nickname for these unwieldy garments was sufficiently damning: they called them “maternity jackets.” On 17 March, the same day that Eisenhower formally recommended the ETO jacket for all ETO troops, Littlejohn wrote to General Maxwell:

The ETO field jacket has been through many bloody battles. Definitely all the troops in this theater want it, and personally I think the troops have come to a sound decision regardless of the fact that I am the sponsor of this gem. ... I have no desire to criticize the model 1943 field jacket as quite likely it fits the problem in some other theater. It is my understanding also that the sweater required to go with the jacket in this theater will not be available for some time to come.37

In April 1944, when Littlejohn reached informal agreement with Clay regarding the provision of the ETO wool jacket to the ETO, he also stated that he and his theater commander did not desire the M1943 jacket, except for paratroopers. But the outcome illustrates a fundamental weakness of all special arrangements arrived at outside of channels.38 The ETO wool jacket would be substituted, in the ETO only, for the serge coat on T/E 21, and thus be brought into the framework of the Army Supply Program, but deletion of the M1943 jacket, an item authorized in all temperate zones, was a far more complicated matter. At the 17 April conference, Col. John P. Baum of the Clothing and Equipage Branch, OQMG Storage and

Distribution Division, assured Littlejohn and Clay that sufficient 1941 olive drab field jackets were available and could be issued until ETO wool jackets began to arrive in the theater. Possibly neither Clay nor Littlejohn understood the full implications of the procedure whereby ASF planners had inserted the ETO jacket into the Army Supply Program as a substitute for the service coat, leaving the world-wide status of the M1943 jacket undisturbed; or perhaps there was a failure of coordination within the bureaucratic mazes of ASF. At any rate, the decision not to accept the M1943 jacket in the ETO was not widely known or clearly understood within ASF.39

On 9 May ASF sent a cable to ETOUSA stating that the M1943 field jacket and high-neck wool sweater were intended to replace the olive drab field jacket .and were for issue in all temperate climates. This combination was to be required eventually for all troops in the ETO, and was to be shipped on requisitions from the OCQM. Littlejohn left this message unanswered, apparently assuming that if no requisitions were submitted, no jackets would be shipped. But on 17 May Colonel Baum informed the OCQM that the stock of olive drab field jackets was being depleted faster than expected, and that M1943 jackets were being set up as substitutes for shipment to the ETO on current requisitions for olive drab jackets. The next

day the ETO informed the War Department that it wanted M1943 jackets only for parachutists.40 Colonel Doriot was convinced that this was an unwise decision, and promptly imparted his views to Clay. Impressed by Doriot’s arguments, based on voluminous laboratory experiments and scientific data, Clay cabled two days later:

Tests have indicated that sweater, wool jacket, and field jacket M-1943 give better all weather protection than overcoat, sweater, and short wool jacket, with a 4 pound saving when dry and up to 14 pounds when wet. Jacket M-1943 combination has been approved for issue by War Department and you may have it if you desire. If you still prefer to retain the overcoat and dispense with sweater and M-1943 issue please verify with SHAEF and advise.41

The requested verification, signed Eisenhower, was forthcoming on 1 June:

Overcoats necessary to provide warmth and protect troops in this theater. Model 43 field jacket only required for parachutists. Jacket field wool OD ETO type and sweater combination will be required in cold areas. Minimum shipments of model 43 jackets field desired in this Theater. This program has the approval of SHAEF and in addition the approval of Generals Bradley, Hodges and Corlett [XIX Corps Commander].42

The above message was only sent after a thorough discussion and concurrences

involving not only the officers named but also Lt. Gen. Walter Bedell Smith, the Chief of Staff, and Maj. Gen. Robert W. Crawford, the SHAEF G-4. Bradley believed that the M1943 jacket was not only unsightly but defective in design; the combat soldier slept in his overcoat, and a short jacket provided no warmth for the legs; the 12th Army Group did not desire the garment. All were in agreement that the M1943 jacket was a superfluous duplicate item. Littlejohn also questioned the validity of laboratory experiments and noncombat field tests, no matter how carefully simulated. Even the Anzio tests, made during combat but in a climate very different from that of the ETO, did not seem to him to be applicable.43

On 15 June, Littlejohn wrote to General Feldman asking precisely how many old style field jackets were still available, and the same day submitted a requisition to NYPE for 2,250,000 sweaters. This was his first formal large-scale requisition for any of the new items displayed by Captain Pounder. In accordance with standing instructions, he had already inquired of the port regarding the availability of wool sleeping bags, and on 24 May had received a commitment for 2,580,000 through October, but the formal requisition did not follow until 22 July, when shipping allocations were available and could be cited specifically. This was in accordance with War Department directives and was the normal OCQM method of operating, but it was not understood by the OQMG, which later accused Littlejohn of excessive tardiness in submitting requisitions.44

The New Table of Equipment and the Compromise Decision

On 1 June 1944, a new T/E 21 was published. Contrary to all expectations, it provided neither an increase in the basis of issue for M1943 clothing nor any clarification of the previous basis. Combat boots and ponchos were listed for the first time, but there was still no mention of wool jackets, or of hoods for the M1943 jacket. A new procedure was introduced grouping all issues into either mandatory or discretionary allowances, and combat boots, the M1943 jacket, and the cotton field cap were all made mandatory in temperate overseas areas, subject to availability and after exhaustion of stocks of substitute items. But the allowances for arctic, cold-temperate, and mountain areas remained discretionary. Accordingly, on zo June Littlejohn cabled the War Department asking for information on clothing and QM equipment that would be used by troops in a winter climate similar to that of Germany and northwestern France.45 This was really a query regarding production and availability of supplies, subjects on

which Littlejohn was never able to obtain satisfactory information. He rightly suspected that the appearance of a new T/E 21 meant that some policy decision or interpretation had been made regarding issue of the new winter garments. Such a decision had been made by the G-4 Division, War Department, but by an almost incredible oversight the OQMG had not been informed. The chain of events leading to this confused situation had begun the previous January.

On 1 January 1944, at a conference attended by representatives of G-1, G-4, AGF, ASF, and the OQMG Military Planning Division, proposals were made to amend the current version of T/E 21, which had been published just two weeks earlier. Specifically, the idea was to expand the special winter clothing allowances for Zone 1 (cold-temperate) and low-mountain terrain to cover the entire temperate zone. A draft amendment to T/E 21, involving eighteen major items, was prepared by the Research and Development Branch, OQMG, approved by AGF, and submitted by the latter to ASF for concurrence on 22 February. ASF in turn requested the views of the OQMG concerning the impact of such a change upon raw materials, labor, production, the civilian economy, and obsolescence of existing stocks.

Maj. Gen. Herman Feldman, replying for The Quartermaster General on 13 March, concurred in the recommendation in principle, but noted the existence of grave limitations upon the productive capacity required to implement it. He recommended that the program be extended over a two-year period, with a limited increase in the basis of issue for 1944, to combat troops in the European and North African theaters only, and with somewhat more generous allowances in all overseas theaters in 1945. Feldman also recommended that the M1943 jacket, wool jacket, and sweater together should replace the overcoat and old style jacket for combat troops. He disapproved the AGF proposal for issue of shoepacs to all combat troops in winter in the temperate zone, since this would require over five million pairs per year, whereas maximum production from all sources, including the use of mandatory orders, was 880,000 pairs in 1944 and 3,225,000 pairs in 1945. Feld-man’s recommendations, coordinated with a careful appraisal of productive capacity, added up to a disapproval of the proposals of AGF (which had actually originated within the Military Planning Division, OQMG), at least in regard to the calendar year 1944. He also stated that the effectiveness of this modified program was based upon receipt of approval and authorization to begin procurement by 1 April 1944.

ASF ignored the OQMG’s deadline and forwarded the correspondence to G-4, War Department, on 15 April, stating its nonconcurrence with most of the original AGF proposals. The ASF recommendations were approved by G-4 on 11 May and forwarded to the OQMG through AGF and ASF. But the correspondence did not reach the OQMG until 29 July, representing a loss of time in transit of seventy-two days and a delay of four months beyond Feldman’s suggested deadline. This administrative oversight imposed a severe handicap on the OQMG in procurement planning. Apparently it also contributed to the curious staff decision whereby the entire NATOUSA theater was considered to

be an alpine or low-mountain area for clothing issue purposes.46

Littlejohn’s inquiry of zo June therefore found the OQMG in a rather poor position to give an accurate and authoritative reply. Colonel Doriot’s answer four days later was clearly based upon an assumption that the AGF recommendations would be approved; possibly he believed that they had already been approved. If he was aware of General Feldman’s contrary recommendations to ASF, he either misunderstood their tenor or disagreed with the appraisal of U.S. industrial capacity on which they were based.47 He predicted that mobile operations would soon bring some of the troops into the cold-temperate area of eastern France and western Germany, and recommended that selection of winter clothing to be issued to all ETO combat troops should be based upon that premise. He referred specifically to

Captain Pounder’s samples and repeated the arguments and recommendations he had made to General Clay a month before, especially regarding the M1943 jacket. He reiterated that this jacket was essential for adequate protection against rain, although he also recommended issue of the poncho. Doriot closed with a suggestion that requisitions be submitted promptly. But Littlejohn felt that he was again being called upon to submit requisitions that might serve as a basis of future procurement, despite the fact that he did not approve of all the items to be procured and despite the fact that General Feldman seriously doubted that such procurement was practicable.

Apparently because Doriot’s letter referred specifically to his overseas representative, the latter was asked to make independent recommendations. On 30 June Pounder submitted almost identical recommendations to Littlejohn in the form of a letter he wished to forward, through official channels, to Colonel Doriot.48 Pounder also forwarded a list of the winter clothing that, he stated, the ETO planned to issue to its troops. This list had been furnished to him by an officer in the Supply Division, OCQM, and was not complete. He pointed out that the ETO uniform was “sadly lacking in water repellent items.” He also remarked disparagingly that “they are counting on the poncho synthetic for protection against wet.” This was a curious, observation, for both Pounder and Doriot recommended the poncho. Pounder had already reported that the ETO was considering ponchos,

and Littlejohn actually requisitioned 250,000 of them on 2 July. This was an experimental requisition to test the reaction of the troops. A week later, Littlejohn wrote to Feldman that all the new items should be handled in the same way:

... for example, the poncho, which in my opinion is definitely superior to the raincoat. It is not my policy to force these new items down the throat of troops but to let them see the new items and then to get a cold blooded, disinterested dissertation thereon giving the good qualities and the bad. ... I am of the opinion that as soon as we can equip a corps or a substantial number of troops with the poncho, we can begin to figure on the raincoat going out of existence.49

Littlejohn would have preferred the nylon poncho, which was reserved for tropical areas in the Pacific. Pounder’s sample item was a slightly heavier version, made of the same material as the authorized raincoat, and therefore could be produced without difficulty. It was easier to manufacture than a raincoat and could be used as a ground sheet under a sleeping bag or even as a shelter half, but was especially useful for individual protection in cold rainy weather, providing that protection against rain which Pounder had declared to be “sadly lacking.” All ponchos had the advantage that one size would fit everyone, and they could be worn over an overcoat, which could hardly be done with a raincoat.

A formal answer to Pounder’s letter was made by Colonel Brumbaugh, who was chief of the OCQM Supply Division at the time. Brumbaugh commented in detail on each of the items he recommended rejecting.50 He agreed that shoepacs were more waterproof than boots or shoes, but they were unsuitable for marching and the soles were not durable. Ski socks were desirable only with shoepacs; use with shoes would require a larger size shoe. Since the overcoat was essential in the ETO climate, the M1943 field jacket was excess; the same applied to cotton field trousers. The bulkiness of leather glove shells with wool inserts hindered use of the trigger finger and made them unsuitable for infantry. Wool gloves with leather palms were preferable. Littlejohn indorsed these views, and within a few days sent Brumbaugh to the United States to expedite a clothing program along the lines indicated. Nevertheless, Brumbaugh was directed to inquire into the availability of the items recommended by Captain Pounder. Colonel Baum informed him that all standard type military shoepacs had been committed to NATOUSA and the arctic reserve, and only 330,000 pairs of shoepacs, all of obsolete types, and 900,000 pairs of ski socks were available. Baum described the trigger finger mitten with wool insert, a new cold-climate combat item, but was of the opinion that the wool glove with leather palm was “more

presentable and warm enough for most occasions.”51 Brumbaugh had been directed to obtain facts and to seek the advice of General Feldman, but not to make decisions.

Another chore that Brumbaugh was to perform was review and completion of a clothing reserve for a 5,000-man task force to operate in a wet-cold or alpine climate, presumably Norway. Part of the necessary clothing had been forwarded to the ETO from Iceland, and the balance was selected in accordance with Doriot’s ideas. But on all major issues the divergence of opinion between Littlejohn and Doriot was so complete that Brumbaugh dealt as much as possible with General Feldman, the Deputy Quartermaster General for Supply Planning, and with officials of the Storage and Distribution Division, even on matters concerning Colonel Doriot’s Military Planning Division.52

Realizing that an impasse had been reached with Doriot, and that not all of Brumbaugh’s questions had been satisfactorily answered, Feldman went to the ETO during the last week in July, just

as the armies were breaking out of the Normandy beachhead. None of Little-john’s experimental requisitions for test purposes had been filled. He still felt that the specific suitability of the OQMG’s new items for his theater had not been demonstrated, but the sudden shift to mobile warfare indicated that the troops might reach the German border ahead of schedule and that some greater provision for operations in a colder climate was necessary. Since the quartermasters of the armies were definitely not available to advise on their requirements for these untried garments,53 the problem had to be approached from the other end—from a survey of what was known to be available. Here Feldman’s detailed knowledge of current supply levels, procurement possibilities, and previous commitments, was invaluable. Littlejohn and Feldman jointly outlined a requirement based upon the availability of 446,000 pairs of improved military shoepacs, the most critical item.54 Supplies of ski socks, ponchos, mufflers, trigger finger mittens, and cotton field trousers were also limited.

Littlejohn found it logical and convenient to frame his requisition as a

project for equipping a type field army of 353,000 men, with normal maintenance reserves. During the period of headlong pursuit he referred to it optimistically as the Army of Occupation project. The formal requisition, J-48, was submitted by cable on 15 August for delivery by the end of October. The next day Feldman, who had returned to the United States two weeks before, gave assurance that the supplies were available. Formal approval, except that half the shoepacs would be obsolete types and poncho deliveries would be deferred, was given on 3 September 1944.55

On 10 August 1944 this clothing program was submitted to the Preventive Medicine Division, Office of the ETO Chief Surgeon, and received the approval of that office. The OCQM planned to provide one field army with cotton field trousers, ski socks, and “a new type of shoepac, in three widths, with proper orthopedic support.” Seventy-five percent of other troops were to receive overshoes.56 Moreover, every man in the theater would be issued a wool jacket, a sweater, and a sleeping bag. OCQM referred to these items as “on requisition,” and there was no hint that they might not be available at the beginning of cold weather.

It might appear at first glance that General Feldman had succeeded in accomplishing a large part of what Captain Pounder failed to do. Such a view would overemphasize clothing design, while ignoring other aspects of supply. Pounder and Doriot had urged Littlejohn to submit requisitions for enough new type winter clothing to equip all the ground combat troops in the theater, a figure in excess of 1,000,000 men. Although Doriot did not believe that such requisitions were procurable in full he did not concur in the idea that a requisition should be limited to what was known to be obtainable. He believed that the OQMG should be given as its objective the procurement of the absolute maximum quantities of the new items obtainable by the use of mandatory orders and “other extreme procurement methods.”57 The garments so obtained should be distributed on a strict priority basis to those troops in the greatest need of them, a process in which Doriot failed to see any difficulties. But such ill-defined procurement and distribution on a when-as-and-if basis was anathema to Littlejohn, who felt that without firm commitments effective local distribution planning within the theater was virtually impossible. By contrast Feldman, a supply man and not a designer, offered the ETO articles that

appeared to be suitable for the changed tactical situation, in quantities that appeared at the time to be available. As a supply specialist he would not be upset because Littlejohn refused M1943 jackets. By August, the OQMG had ordered over 7,000,000 of them from manufacturers, and presumably any reasonable number could be shipped at short notice if the Chief Quartermaster changed his mind.

To anticipate the final outcome, Littlejohn finally did change his mind and accept the M1943 jacket, but only after it had become clear that nothing else was available. The overcoat worn over the M1943 jacket was a combination that pleased neither Doriot nor Littlejohn, but it was one of the variety of motley outfits still being worn by combat troops in early 1945. Once the ETO had approved the M1943 jacket, the War Department cabled that issues were to be made to all troops as authorized in the current TAE 21, and that olive drab field jackets, winter combat jackets, and similar substitute items were to be withdrawn as soon as possible. This directive merely underlines the lack of effective liaison between the two headquarters, since a shortage of M1943 jackets had already developed, making compliance impossible. Moreover, the troops fortunate enough to have winter combat jackets refused to part with them. The order also did nothing to clarify the status of the overcoat, authorization for which was not withdrawn, either then or later.58

Receipt and Forwarding of Winter Clothing

The First Winterization Program 7 September-13 October 1944

On 7 September, the same day that Colonel Busch wrote “It is getting cold up here,” Littlejohn sent letters and memos to each army quartermaster and each base section quartermaster in the theater, and also to his deputy back in the United Kingdom.59 The burden of each message was the same. Supplying winter clothing to the troops was almost entirely a problem of local transportation, and since the OCQM did not control any trains or trucks, quartermasters at all levels must put pressure on their respective G-4’s and persuade them that the allocation of tonnage for moving Class II items had to be radically increased. Moreover, the pipeline from Cherbourg to the armies was now over 400 miles long, without any intermediate depots or effective Quartermaster control anywhere along the route. If pilferage, distortion of balanced tariffs, and interminable delays were to be avoided, supplies must be sent direct from the United Kingdom by air or by LST to specific small ports. Two days later, armed with rough estimates of requirements from McNamara and Busch, Littlejohn made a formal request to General Stratton, the G-4 COMZ, for increased cross-Channel transportation and revised priorities. He wanted the Quartermaster tonnage allocation for September raised from 62,000 to 88,750 long tons. He pointed out that for the

period June–August 1944, the specific allocation of QM Class II tonnage had been 55,000, but actual receipts had only been 53 percent of that amount. Moreover, reports from the United Kingdom indicated that the 62,000 tons currently allocated for clothing and individual equipment bore such a low priority that they could not be shipped before the end of September. He proposed to reduce his Class I and III tonnages from the United Kingdom by 50 percent, and urgently requested a priority authorization for 50,750 long tons of Class II items, broken down as follows:

| Items | Tons |

| Winter clothing program | 10,000 |

| Winter tentage program | 10,350 |

| Combat maintenance | 29,500 |

| Class B and X clothing for POW’s | 900 |

In addition, his Class IV allocation should include 200 long tons of winter clothing to be sold to officers and nurses.

The clothing for enlisted men was intended primarily for 750,000 troops actually in combat—the First and Third Armies on the German frontier, and one corps under Ninth Army besieging Brest. This was normal winter clothing, not special items. It included both initial issues and necessary replacement articles, and the complete issue amounted to 25 pounds per man. (Table 18) Littlejohn explained that distribution had to be completed by 1 October if the efficiency of the troops was to be maintained, and requested that 6,000 tons of clothing for troops in the forward areas, and also the clothing for sale to officers, be moved by air.60 Clothing for Ninth Army and COMZ troops could easily be transported by ship—preferably by LST to small ports where they could be unloaded and expedited by Quartermaster troops. Littlejohn clearly wished to keep these special shipments away from Cherbourg, where more than one hundred ships were waiting to unload and inventory and forwarding procedures were alarmingly inefficient. But Stratton decided that the current overriding priorities for movement of POL and ammunition by air should not be changed. In spite of a personal appeal by Littlejohn, Bradley supported Stratton. Bradley’s comment afterwards was:

When the rains first came in November with a blast of wintry cold, our troops were ill-prepared for winter-time campaigning. This was traceable in part to the September crisis in supply for, during our race to the Rhine, I had deliberately by-passed shipments of winter clothing in favor of ammunition and gasoline. As a consequence, we now found ourselves caught short, particularly in bad-weather footgear. We had gambled in our choice and now were paying for the bad guess.61

Even in the face of such high level opposition, Littlejohn remained convinced of the necessity of his program and sought alternate means of transportation. At a time when the pursuit was slowing down for want of gasoline this was no simple problem, but the Chief Quartermaster explored every possibility and overcame many obstacles. LSTs and coasters were in short supply, and most of the lower priority items had to go to Cherbourg on Liberty ships. Reims had

Table 18—Summary of First Winter Clothing Program, 7 September 1944

| Item | Basis | Estimated requirements by 1 October | Weight per unit, packed | Total weight, lbs. |

| Overcoats or mackinaws | 1 per man not equipped on arrival | 750,000 | 9.00 | 6,750,000 |

| Gloves, wool (pair) | 1 per man not equipped on arrival | 750,000 | .36 | 270,000 |

| Undershirts, wool | 1 per man to Army troops | 750,000 | 1.06 | 795,000 |

| Drawers, wool | 1 per man to Army troops | 750,000 | .86 | 645,000 |

| Blankets, wool | 1 per man | 1,500,000 | 4.65 | 6,975,000 |

| Cap, wool, knit | 1 per man not equipped on arrival | 750,000 | .18 | 135,000 |

| Socks, wool (pair)* | 2 per man | 2,600,000 | .38 | 988,000 |

| Laces, shoe (pair)* | 1 per 2 men in Armies | 350,000 | .02 | 7,000 |

| Laces, legging (pair)* | 1 per 2 men in Armies | 350,000 | .02 | 7,000 |

| Shoes, service (pair)* | 1 per man in Armies | 750,000 | 4.83 | 3,622,500 |

| Shirts, wool” | 1 per man in Armies | 515,000 | 1.50 | 772,500 |

| Trousers, wool’ | 1 per man in Armies | 515,000 | 2.20 | 1,133,000 |

| Totals—pounds | 25.06 | 22,100,000 | ||

| Totals—long tons | 9,866 |

* Represents estimated necessary replacements to troops now on the Continent. These are not considered as initial issues.

been selected as the inland Class II distributing point, and to obtain trains for clothing he arranged to divert ships carrying 800 tons of rations per day (equal to two trains) from Cherbourg to Morlaix, on the northern coast of Brittany. A considerable part of the smaller but more vital portion of the winterization program, involving airlift to the First and Third Armies, was carried out as planned through the personal intervention of General Spaatz. Since transport aircraft were not available, he provided bombers to carry 41 percent of the required clothing to forward airstrips. Perhaps the fact that Littlejohn had personally arranged for Spaatz and his staff to receive 100 sets of the coveted officer type of ETO uniforms a week earlier made this type of informal staff coordination easier.62

Other expedients outside the tonnage allocations system were employed to move clothing forward. On 16 September three DUKW companies,

optimistically moving up to support a Rhine crossing, were used to bring more than 300,000 sets of winter underwear to First Army.63 Moving 1,000 tons of clothing to the Ninth Army through small Brittany ports was comparatively easy because an LST was available for this shipment. Since Liberty ships could not enter the shallow harbors, these ports were not crowded and service personnel of the army were available to assist in unloading. By contrast, at such deep-water ports as Cherbourg, Le Havre, and Rouen, only 12 Quartermaster ships could be berthed at one time, and at the end of September 61 shiploads of Quartermaster cargo including 12 loaded with clothing and equipment, were waiting to discharge.64

A complicated aspect of the winterization program involved the duffel bags that divisions of Third Army had brought to the Continent. These had been stored in various locations within the original beachhead during July. On 9 September the Third Army quartermaster asked ADSEC to send forward over 1,200 tons of the bags for three divisions, and later another shipment for three more divisions was requested. Most of these bags could be located, and had been trucked to the nearest railroad by 25 September, but the sequel was far from satisfactory. Some had been pilfered and no longer contained either blankets or overcoats. The owners of some of the bags had become casualties. Those bags that reached their rightful owners intact usually duplicated items already issued. Naturally, rail transportation was charged against Third Army’s Class II tonnage allocation. The whole procedure was wasteful and inefficient.65

The procedure recommended by Littlejohn, and prescribed for First Army troops by Colonel McNamara, also ran into difficulties. The duffel bags of winter clothing that FUSA units turned in before leaving the United Kingdom in June should, in theory, have been salvaged and returned to stock. On 8 September Littlejohn noted with concern that the United Kingdom inventory of overcoats was only 500,000, whereas he believed it should be twice as large.66 Sorting and returning to stock the overcoats turned in by the combat troops before their departure should have been simple, but salvage operations had been severely hampered by loss of the more experienced salvage units, which were naturally the first to be sent to the Continent.

Nevertheless, bearing in mind the objectives of this first winterization pro-gram—to equip combat troops only—it was very successful. At the end of September the First Army chief of staff set up priorities for the currently arriving winter clothing, giving first priority to infantry divisions and last to army troops. Early in October a full issue of regular winter clothing to First Army was completed, with the exception of a 50 percent shortage in arctic overshoes,

an item not included in the original list. At the same time 6,000 of the new sleeping bags were issued to each division, enough to give each man either four blankets or a sleeping bag and two blankets. Difficulties with the size tariff led to shortages in the medium sizes of field jackets, wool olive drab clothing, and shoes. A similar shortage of wool socks was overcome in military laundries by shrinking size 12 to smaller sizes required in the army depot.67

Meanwhile, by 30 September all Third Army troops had a third blanket. Overcoats had been distributed to all except army troops, demonstrating that, like General Bradley, TUSA regarded the overcoat as a combat item. Early in October issues to Third Army similar to those in First Army were completed, and by the end of the month the only shortages were overshoes, raincoats, and leggings. Third Army had received about 4,500 tons of Class II and IV supplies during October—including 1,194 tons delivered by air.68

One additional fact might be noted here. Upon his return from the United States in late July, Brumbaugh was appointed Deputy Chief Quartermaster (Rear), replacing Brig. Gen. Allen R. Kimball. There were several reasons for this appointment, despite Brumbaugh’s openly expressed preference for a more active assignment. First, there were tremendous quantities of used clothing in the United Kingdom, although progress in salvage and inventory left much to be desired. Brumbaugh, as a clothing specialist, was an ideal man to thaw this frozen asset. Moreover, his ETO experience fitted him to administer what was becoming essentially a British civilian organization, now that the American units were leaving for the Continent. General Kimball, a senior Quartermaster officer but a recent arrival in the ETO, lacked such specialized experience. An additional problem arose late in August, when the U.K. Base Section was transformed into a semi-autonomous headquarters under the command of Brig. Gen. Harry B. Vaughan, Jr. Littlejohn remembered his rather unsatisfactory relationship with the Forward Echelon, COMZ, when General Vaughan commanded that organization, and decided that the situation demanded an unusually competent and forceful Quartermaster representative in this rearmost echelon of ETO supply. Brumbaugh was therefore given the additional designation of Quartermaster, United Kingdom Base, and remained in London despite the fact that there was no really qualified clothing expert to replace him in the OCQM. Lt. Col. Thomas B. Phillips was confirmed in his temporary position as chief of the Supply Division, and several junior officers of even less experience became branch chiefs.69

The Replacement Factor Controversy

At a staff conference in Paris on the morning of 13 October, Littlejohn was able to give a very satisfactory report on progress in winterizing the combat troops. He displayed an impressive chart which showed that, except for blankets and overshoes, quotas for every item of the winterization program had actually been exceeded. But Littlejohn

referred disparagingly to his achievement as a “so-called winterizing program,” explaining that it had merely met preliminary demands brought on by unexpectedly early cold weather. Now he was faced with the real supply problem resulting from accelerated wear and tear of most items of clothing and equipage, and had recently been forced to place heavy emergency demands upon the zone of interior because “regardless of whether this current replacement factor holds true for the whole year, the supplies must be here to meet the known demands.” It was therefore imperative that the transatlantic tonnage allocation for QM supplies for November be increased by 172,275 measurement tons. Littlejohn did not need to mention that this would be an increase of 52 percent over his October allocation, and if granted would require sharp cutbacks by the other technical services.70

That same afternoon Littlejohn covered much the same ground in an interview with the press, but with somewhat different emphasis. He described the disrupting effects of the unexpected tactical pursuit, which had created local shortages of clothing, and the dramatic airlift, which had overcome them in the forward areas. But AAF and service troops were still seriously short of clothing and blankets. The Chief Quartermaster explained that rates of wear and tear and of loss had been badly underestimated, and that the rate of maintenance shipments from the United States would have to be increased 250 percent to take care of these revised requirements. Consequently, the productive capacity of the United States must continue unimpaired. Doubtless Littlejohn was referring to increased discussion of the imminence of victory in the American press and wide publicity that had been given to recent contract terminations by the Army. He carefully refrained from referring to delays in current production in the United States, a matter that had been publicized by the War Production Board late in September, but at least one correspondent, David Anderson of the New York Times, said that such production was “months behind,” and also stated that “the men fighting on the rim of Germany were ill-equipped for winter.”71 This unfortunate statement was only partly true at the time of the press conference; indeed the ostensible reason for calling in the press had been to explain how local distribution problems on the Continent had been overcome.

The Times article promptly evoked a demand for explanations from Somervell to Eisenhower and Lee. The head of ASF failed to understand the need to rush clothing by aircraft, and stated that prior tot October he had received no reports that War Department replacement factors were inadequate. Littlejohn explained to Lee that he had

“stressed the part that air is playing in the supply of the armies.” He also stated that he had made repeated informal reports on the inadequacy of the War Department’s replacement factors, and that during the last month he had been forced to submit two very large emergency requisitions for additional clothing and equipage.72

The above exchange of cables marks the emergence of replacement factors as the major consideration in computing and justifying specific clothing requirements from the ETO. Requirements specialists in the OQMG felt that this was a misuse of replacement factors, which represented long-term trends and were used primarily in computing war production programs at the national level. They recognized that the first stages of any military operation were often marked by unusually heavy demands for Class II supplies, but from their point of view such demands should be met by special projects, such as the PROCO procedure that had been authorized during the build-up for OVERLORD. Such projects were filled from special reserves and did not disrupt the orderly computation of long-term replacement factors. But Littlejohn had believed even before D-day that the current replacement factors were inadequate, and he had made an unsuccessful attempt to set up a special clothing reserve by the use of PROCO requisitions. When ASF disapproved his special projects as unjustified, he became convinced that PROCO procedures were ineffective and also that basic requirements statistics in the zone of interior were faulty and would have to be revised. Officials in the OQMG did not agree. That ASF had disapproved Littlejohn’s PROCO requisitions was unfortunate, but not germane to their problems. Their current replacement factors should stand until new long-term trends had been confirmed.73 Littlejohn, on the other hand, felt that the primary objective of the Quartermaster Corps was to fill the needs of the combat soldier, no matter how unpredictable they might be. For that purpose he was ready to follow procedure, distort procedure, or overturn it altogether. His own description of what had occurred on the Continent during the initial period of heavy combat vividly explains the new and unexpected trend in replacement factors:

Normandy is covered with a series of hedges. Each small plot of ground on the farms is completely surrounded by these tall hedges which carry thorns. Furthermore, in the advance across Normandy, the local actions in which small units were engaged frequently consisted of a life-and-death race across a 50-yard space. The American soldier skinned down to the clothes he had on, his rifle, his ammunition belt full of ammunition, and one day’s ration. The blankets, the shoulder pack, overshoes, were left in a dugout which he had made for himself. Raincoat and blanket were usually at the bottom. The shelter half was staked down on top of the hole and covered with about two feet of dirt. The items left behind or destroyed by the soldier as indicated above, were scavenged by the natives. Another important thing in the high consumption of

clothing and equipage was the mud. If one dropped his knife, fork, spoon, or mess kit at night it disappeared in the mud and had to be replaced. At the close of the battle of Normandy it was necessary for me to completely re-equip approximately 1,000,000 American soldiers almost as if they were completely naked.74

The real point of contention was whether recent demands from the Continent represented a temporary situation or a new trend. If Littlejohn’s view was correct, prudence demanded that the War Department revise its production program immediately instead of waiting until its reserves had been depleted. It was his contention that for at least three months the requisitions from the armies had not reflected their real requirements. Any report of depot issues to date was meaningless unless the unfilled demands of the armies were included, and the same applied to any computation of replacement factors based upon issues alone. Littlejohn’s only effective method of assembling a reserve to meet the future needs of the armies was to compute his authorized level of Class II and IV supply (sixty days) in terms of observed, rather than administratively imposed, factors. Gregory, on the other hand, contended that clothing and equipment had been lost during the pursuit rather than expended during heavy combat, and that the existence of a valid new trend had not yet been demonstrated.75

The OQMG had sent a factor-computing team to the ETO before the June landings, and it set up reporting procedures and began to collect data in July. Like other theaters, the ETO had been submitting reports of matériel consumed since mid-1943, but under combat conditions this was a far more complicated process, since the unpredictable element of combat losses was now added to the factors of wear and tear. Capt. Harold A. Naisbitt, who had been specially trained in the Requirements Branch, OQMG, reported that current administrative directives of COMZ and the OCQM were adequate, but that in many cases they were not being followed.76 The maintenance factor team’s first report, covering the period from 6 June to 28 July (D+52) was so crude that Littlejohn dismissed it as a generalized statement requiring confirmation. On 8 August he wrote to Colonel Franks, the acting quartermaster of ADSEC:

... I must have definite information upon which to raise the ante for requisitions. Of course, as you know, if the situation is serious we will issue all the stocks we have and tell Pembark to furnish replacement. Where is my team that was sent to the Continent to do the maintenance factor job? When are they going to give me some new maintenance factors? The other day you gave me an over-all statement that maintenance was running at the rate of 2½ times the current factors. Please expedite this information so that we can use it in the review of requisitions.77

Crude and unsatisfactory though they were, the factors submitted on 4 August

constituted the last valid report received in over a month. The pursuit across France had already begun, and during that phase of operations improvement in the mechanics of reporting was meaningless, for the clothing issues reported upon were largely confined to COMZ and AAF units. While the armies were engaged in pursuit they were mainly interested in receiving food and gasoline; their requisitions for clothing and personal equipment averaged about 10 percent of normal requirements and actual receipts less than 3 percent.78