Chapter 12: China, Burma, and India

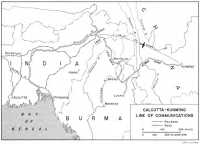

The fall of Rangoon in March 1942 and the subsequent occupation of Burma by the Japanese cut the Burma Road, the last practicable overland route linking China with the other Allied powers, and left as an immediate alternative only a tenuous air supply line from Assam in northeastern India over the Himalayas (the Hump).1 The sole remaining base from which communications to China could be restored was India, and it was there that the United States concentrated its effort to develop the airlift and, through the recapture of Burma, to reopen the land route to China. This effort was designed to support American air operations in China and to deliver lend-lease supplies intended to assist China in reorganizing and increasing the combat efficiency of her armies. It involved the deployment of relatively small and scattered American forces, principally Air Forces and construction and other service troops, and the support of the north Burma campaigns, which the Chinese Army in India fought with the assistance of British and American forces. (Map 8)

The Strategical and Logistical Setting

From the outset, transportation loomed as a major problem in the task of delivering the supplies that would keep China in the war and eventually enable her to take the offensive against Japan. Indian ports were limited in number and were located 10,000 to 12,000 miles from the United States. None was equipped to handle greatly expanded traffic. Since the highway system, with the exception of that on the northwest frontier, was undeveloped, ports were served mainly by railroad, supplemented by coastwise shipping and river transportation. Before the war the possibility that India would be a base for operations to the east had received scant consideration. When, contrary to expectation, Assam became the scene of airfield construction and the supply base for construction and combat forces moving into Burma, transportation facilities in that area were found to be sadly deficient.

Although Assam was the main operational center, it was at first necessary to use ports on the west coast of India since eastern ports were blocked by Japanese activity in the Bay of Bengal and the Indian Ocean. Supplies had to be moved an additional 2,100 to 3,000 miles, after being discharged, in order to reach their destinations in Assam and China. From Karachi, the first major American port of entry, supplies were hauled across India by rail to eastern Assam for local use or for movement by air over the Hump to the Kunming area, whence they were transported to Chungking and to advanced Chinese bases by rail, highway, river, and coolie or animal transport.

The Indian railway system was

Map 8 Calcutta–Kunming line of communications

ill-prepared to handle additional traffic. The virtual closing in early 1942 of the eastern ports, particularly Calcutta, placed a heavy burden on trans-India rail facilities, lengthening hauls and forcing movement by rail of materials normally shipped on coastwise vessels. The worst bottleneck in the rail system was the meter-gauge railway serving the eastern frontier. This line was extremely limited in capacity, and the Brahmaputra River was unbridged. The railroads were centrally controlled by the Railway Department of the Government of India, and were supervised by a civilian railway board. Although the board exercised control in matters of general policy, individual railroads worked as separate entities and were not fully coordinated.

Inland water transport, concentrated mainly on the Ganges and Brahmaputra Rivers and their tributaries, supplemented the rail facilities in east Bengal and Assam. Handled exclusively by civilian firms, river transportation was slow and subject to seasonal disruption. Transfer of craft to the Persian Gulf area in 1941 and 1942 cut into carrying capacity, and there was little coordination of rail and river movements.2

The Pioneer Period

The task of receiving and forwarding lend-lease and U.S. Army supplies from the Indian ports was given to Brig. Gen. (later Lt. Gen.) Raymond A. Wheeler, then heading the U.S. Military Iranian Mission. On 28 February 1942 the War Department placed him in command of the Services of Supply, under Lt. Gen. (later General) Joseph W. Stilwell, commander of the U.S. Army forces in the the China–Burma–India (CBI) theater. Wheeler and a small staff arrived at Karachi on 9 March and there established SOS headquarters. Three days later the first contingent to arrive in CBI, air force troops diverted from Jaya, debarked. Borrowing men from this group as well as from the Iranian mission and groups of casuals destined for Stilwell’s headquarters in China, Wheeler organized a temporary staff and got port and other operations under way.

At this time, the resources available to the U.S. Army were meager. Shaken by the Pearl Harbor catastrophe, scarcely started in “the battle of production,” and faced with the necessity of holding the enemy in Europe and the Pacific, the United States could make only limited provision for the war in Asia. Instructed to live off the country insofar as possible, Wheeler decided to decentralize supply operations to the areas where American troops would be stationed in number. After the arrival of the first service troops in May, he moved his headquarters to New Delhi where British General Headquarters (India) was located, and divided the SOS organization into geographical base and advance sections. As SOS activities fanned out from Karachi across India to Bengal and up to Assam and China, existing sections were consolidated or inactivated and new ones created.

The SOS organization had crystallized by April 1943. Base Section One, with headquarters at Karachi, controlled SOS activities in western India. Base Section Two, with headquarters at Calcutta, exercised jurisdiction over the area along the route to Assam. Advance Section Two (later Intermediate Section Two), with headquarters first at Dibrugarh and later at Chabua, received supplies for China or Burma. Base Section Three (later Advance Section Three) had its headquarters at Ledo, Assam, the base for construction and for the projected combat operations in north Burma. Advance Section Three, established at Kunming in June 1942, conducted SOS operations in China. Later, Advance Section Four was to be set up at Kweilin to handle supplies for U.S. forces in east China. The two sections were consolidated in January 1944 to form a single SOS agency for China. Except for certain exempted installations and operations directly under control of SOS headquarters, section commanders were responsible for all SOS activities within their jurisdiction.3

Initially, U.S. Army transportation operations were controlled by the section commanders since no theater or SOS transportation organization existed. As the sections expanded, they tended to develop transportation organizations and, depending on the activities in the locality, assigned water, rail, air, and motor transportation officers. When in April 1943 a Transportation Section was organized at SOS headquarters, it was given the status of a special staff section. Under the command of Col. Otto R. Stillinger, this

section dealt primarily with planning for motor, rail, and inland water operations. Stillinger reported to G-4 and the chief of staff, communicating through these channels with the base and advance sections, which directed actual operations.4

The decentralization of U.S. Army transportation operations and the establishment of a transportation section with purely staff functions were natural outgrowths of the situation in CBI. Higher strategic priorities afforded other areas precluded the large-scale provision of American troops, equipment, and supplies. In addition, CBI, as the arena of diverse and often conflicting national interests, was perhaps more subject to uncertainties of planning than any other over-sea area. These two factors, together with the formidable barriers of time and space, resulted in a limited development of American transportation activities in the area. In line with War Department directives, the U.S. Army wherever possible relied on the British for transport and geared its SOS organization to make use of the resources locally available. Indeed, when the British in the summer of 1942 proposed that the Americans take over bottleneck portions of the railroad in Assam, Stilwell and Wheeler rejected the idea.5

Aside from air operations, American transport activities were confined to base hauling and to small-scale port operations at Karachi, Bombay, and, as soon as tactical conditions permitted, Calcutta. During 1942 Karachi, which received virtually all U.S. Army cargo and China Defense Supplies (CDS), discharged only 130,342 long tons of such freight. Arrangements for rail or river movement to the interior were made through British movements authorities. In October 1942 the U.S. Army assumed responsibility for construction of the Ledo Road and, toward the end of the year, began operations. As in the case of the ports, transport in support of this project was the responsibility of the section commander. In China, which received only a trickle of supplies over the Hump, the U.S. Army was almost totally dependent on the Chinese for interior distribution from the Kunming air terminal.

As long as the flow of supplies from the United States was small, the Indian transport system was able to absorb it, albeit with some difficulty. By early 1943, however, plans were in the making for greatly expanded operations. In January, at Casablanca, the Allied planners agreed to undertake ANAKIM, an operation to retake all of Burma, and tentatively set up for mid-November 1943. Following the conference, General Somervell, the Commanding General, Army Service Forces, visited India and discussed logistical problems with Wheeler. At Somervell’s request, Wheeler submitted a plan for the support of 100,000 American troops in China, assuming the early conquest of north Burma, followed by the recapture of the remainder of the country, including Rangoon. His plan outlined the personnel and equipment required for motor transport deliveries on the Ledo–Burma Road and for a large-scale barge operation on the Irrawaddy River northward from Rangoon. Upon its receipt in Washington, the plan was used by the ASF as a basis for the procurement of vehicles and barge-line equipment.6

The strategic assumptions upon which the Wheeler plan was based were soon altered. At TRIDENT, in May 1943, the major emphasis was placed on the support of an air offensive in China, and ANAKIM was watered down. The Combined Chiefs of Staff set a goal of 10,000 tons a month for Hump deliveries by November 1943, and made definite commitments only for a campaign to retake north Burma in the 1943–44 dry season. The ensuing expansion of base installations in Assam and Manipur State in support of the Hump airlift and the projected Burma campaign created a heavy demand for supplies and equipment. To meet these requirements, supplies were laid down at Calcutta, now emerging as the major American cargo port, far in excess of the capacity of the inadequate line of communications leading into Assam. During the latter half of the year, congestion at Calcutta and along the rail and river routes reached serious proportions and endangered construction, airlift, and combat operations.7

Quadrant—Planning and Implementation

The TRIDENT decisions had been reached without coming to grips with the logistical problems involved in their execution. This task was undertaken in August 1943 at the QUADRANT Conference at Quebec. There, the logistical requirements for augmented Hump deliveries and construction and combat operations to re-establish land communications with China were determined. In the implementation of these decisions, beginning in the fall of 1943, the U.S. Army received the means with which to break the bottleneck between the port of Calcutta and operational centers in Assam and to carry forward projected operations.

During his visit to India in February 1943, General Somervell had analyzed the central logistical problem as the buildup of communications to Assam and from Assam into Burma and he believed that “with firm purpose the Assam LOC [line of communications] could carry far greater tonnage than it was then doing and furthermore, far greater tonnage than the British had stated was possible.”8 At QUADRANT this belief was translated into action when Somervell joined with his British counterpart, General Sir Thomas Sheridan Riddell-Webster, to present a plan for the monthly air and truck delivery to China of 85,000 short tons of supplies and up to 54,000 short tons of petroleum by 1 January 1946. This goal depended on the development of the capacity of the Assam LOC from 102,000 short tons monthly, the estimated capacity for November 1943, to 220,000 short tons, and the construction of pipelines to carry an additional 72,000 short tons of petroleum monthly.

In making their proposals, Somervell and Riddell-Webster noted that the Joint Chiefs of Staff had agreed to provide special American personnel, equipment, and supplies to construct and operate the Ledo–Kunming route, and also to achieve the increased tonnage on the Assam LOC. There was a specific proposal to establish an American barge line on the Brahmaputra River to deliver 30,000 short tons a month to Dibrugarh. They also recommended that the Supreme Commander, Southeast Asia, soon to be appointed, be

directed to take the necessary action for the development of transportation to attain the target figures, and that pending his assumption of command, the Commander-in-Chief, India, be charged with primary responsibility.

The plan was incorporated by the CCS into their over-all strategic plan for Asia. In their final report, the CCS placed the main emphasis on the establishment of land communications with China and the improvement and security of the air route. These aims were to be furthered by operations to capture Upper Burma, preparations for amphibious operations in the spring of 1944 against a point to be decided, and a continued build-up and increase of air routes and air supplies to China. To provide the means with which to support these operations, the CCS adopted Somervell’s and Riddell-Webster’s plan.9

In the months following the conference, negotiations were begun with the British regarding the use of American troops and equipment in the development of the Assam LOC. The proposed barge line on the Brahmaputra, intended to supplement civilian river lines, was accepted without reservation, but planning for rail operations proved more difficult. When the Americans first proposed militarizing and placing American railway troops on the bottlenecked meter-gauge portion of the Bengal and Assam Railway leading across Assam to Ledo, Government of India officials vetoed the idea, believing that the railroad was doing as well as could be expected and fearing adverse effects on the civil economy and political repercussions.

The need for drastic increases in the movement of supplies to Assam brought continued pressure for militarization of the railroad. While Somervell and the Chief of Transportation, General Gross, were on a visit to India, an intercommand meeting was called in New Delhi in October 1943 to consider means of speeding up the development of the Assam LOC. Among the participants were Vice-Adm. Lord Louis Mountbatten (the Supreme Allied Commander, Southeast Asia), representatives of General Headquarters (India), the War Transport and Railway Department of the Government of India, and American officers, including Stilwell, Wheeler, Somervell, and Gross.

At this meeting Somervell pointed out that a 50 percent increase in tonnage was required by April 1944 if commitments to China were to be met. If the Government of India was unable to achieve this goal, he asserted, sufficient American railway troops could be provided to assure its accomplishment. When British and Indian railway officials were unable to guarantee the desired 50 percent increase, Mountbatten considered it necessary to press the Government of India to accept the American offer. After the conference, opposition diminished and negotiations proceeded smoothly.10 A Military Railway Service was established, railway troops were brought in, and the Americans took control of the meter-gauge lines between Katihar and Ledo, effective 1 March 1944. Meanwhile, additional port troops and equipment had arrived at Calcutta,

an American barge-line organization had been established in India, and inland waterway troops and equipment had been shipped from the United States.

Organization of a Transportation Service

Expanded American transportation operations brought into being a Transportation Service with command as well as staff functions. Maj. Gen. W. E. R. Covell, who assumed command of SOS in CBI in November 1943, considered transportation “our most difficult and most important problem.”11 One of his first actions was to propose reorganization of SOS along the lines of a zone of communications. Included was a specific recommendation for the establishment of a transportation service that would operate under a division of the zone of communications headquarters. Although his plans were not accepted in their entirety, the proposal for the creation of a transportation service was adopted.12

The Transportation Service of SOS was established at New Delhi on 1 January 1944 to direct, coordinate, and supervise all transportation functions of the U.S. forces in CBI. General Thomas Wilson was appointed commanding general and acted as transportation officer on Covell’s staff. Wilson, former Chief of Transportation, Southwest Pacific, had been transferred to CBI at the request of Wheeler in October 1943 in order to replace Colonel Stillinger, who was to return to the United States. Wilson’s arrival coincided with that of Covell, and the two worked closely in organizing the Transportation Service.13

In addition to his staff functions, Wilson was given command of the Military Railway Service, the American Barge Lines, and the Bombay Port of Debarkation, which was removed from the jurisdiction of Base Section One and established as an exempted installation on 31 December 1943. The order setting up the service also attempted to coordinate its functions with those of the base and advance sections. Transportation officers, to be assigned to the staff of each section command, would receive operational and technical instructions directly from Transportation Service.

A rather elaborate organization was outlined, but it did not go into effect immediately, chiefly because of a lack of personnel. An acute shortage of qualified officers continued through the early months of 1944 and retarded full realization of the new organization. The situation was disturbing to Wilson, and in April he reported to Washington that it was getting worse rather than better.14

Despite this handicap, the Transportation Service had begun to function. Staff and operating divisions were set up separately or consolidated, according to available personnel, and liaison channels were established to coordinate American and British transportation efforts. Wilson personally maintained constant contact with the Director of Movements, General Headquarters, India, and Transportation Service officers attended meetings at New Delhi of the British military and Government of India agencies that controlled rail

movements and coordinated port and shipping operations. When Southeast Asia Command (SEAC) headquarters were set up at Kandy, Ceylon, a Transportation Service officer was sent to Colombo to act as port officer and to maintain liaison with SEAC and the British Eastern Fleet.

During this early period, Wilson, together with Covell and Brig. Gen. Gilbert X. Cheves, the new Base Section Two commander, devoted his major effort to breaking the bottlenecks at the port of Calcutta and along the Assam LOC. Arrangements were made with the British to give the U.S. Army exclusive use of the modern King George Docks at Calcutta and to open Madras as an overflow port. The British were also persuaded to appoint a port controller at Calcutta and to accept an American officer as one of his deputies. With the assistance of pressure from Washington, a committee was set up to control and coordinate movements over the Assam LOC and a Transportation Service officer was appointed as a representative.15

Provision was first made for the extension of the Transportation Service into China in February 1944, when Wilson assigned Col. Maurice E. Sheahan to handle the critical transportation situation there. Sheahan, Wilson’s deputy in China, also acted as transportation officer of Advance Section One and controlled transportation operations into the forward areas beyond the section’s boundaries. Under his direction a significant motor transport operation was developed in support of the advanced airfields of the Fourteenth Air Force in China.

In June 1944 the Transportation Service was reorganized. The chief of staff was redesignated executive officer, and staff and operating divisions were consolidated into four sections each. The Military Railway Service and the American Barge Lines continued to be assigned to Transportation Service, and the Bombay Port of Debarkation remained an exempt station under Transportation Service. To a large extent, the reduction of the Transportation Service organization was due to a shortage of personnel and the curtailment of what had originally been planned as a large-scale American barge-line project. Perhaps equally important was the fact that Covell’s plan for a centralized zone of communications organization, of which Transportation Service was to be a part, was never implemented and, as a consequence, the section commanders retained a large degree of autonomy.

Although Transportation Service gave technical and operational guidance to SOS sections, section commanders continued to control transportation operations within their areas. Base Section Two, for example, retained command of the Army port organization and troops at Calcutta along with base motor, rail, air, and liaison activities. In Advance Section Three, convoy operations on the Ledo Road were directed by a provisional organization under the section commander. Despite Wilson’s efforts to bring the operation under Transportation Service, his functions relating to motor transport in Burma were limited largely to planning for the opening of the road to China. During 1944 Intermediate Section Two also provided an example of independent

transportation operations, conducting a convoy route from the Bongaigaon railhead to Chabua, the main base for Hump deliveries from Assam to China.16

Whatever the deficiencies in the duality of organization and authority, they were not serious enough to impair transportation operations. There was a large degree of cooperation between Transportation Service and section commanders. As the major transportation problems moved toward a solution during 1944, there was little pressure for change.

General Wilson returned to the United States in July 1944 and was succeeded by Col. (later Brig. Gen.) Edward C. Rose. During Wilson’s command, transportation operations had been greatly expanded. Until December 1943, two port companies were the only Transportation Corps units in the command. By the middle of 1944 there were on duty two port battalion headquarters, ten port companies, a railway grand division, five railway operating battalions, one railway shop battalion, and two harbor craft companies. American rail and barge operations had been instituted and the bottlenecks at Calcutta and along the Assam LOC had been broken; American motor operations had commenced in China; close relations with British authorities had been developed; and plans had been formulated for motor transport on the Ledo–Burma Road. Covell reported that Wilson had done “a splendid job in building our Transportation Service from practically nothing.”17

Under Rose, the Transportation Service organization underwent several changes in the latter half of 1944. To its existing air transportation activities, consisting largely of screening requests for priorities for air movement of SOS personnel and cargo from New Delhi, was added responsibility for administering the Army’s contract with the China National Aviation Corporation (CNAC). This airline, jointly owned by the Chinese Government and Pan American Airlines, flew lend-lease materials to China. Beginning in July 1944 the Air Section of Transportation Service kept a record of CNAC operations, insured compliance with the contract, and assisted CNAC in solving supply and other problems. This responsibility was retained until 1 September 1945, when it was turned over to the China Theater.

Another new development occurred in September 1944, when direction of transportation projects in China was turned over to Advance Section One, and Sheahan’s organization became a special staff section under the section commander. In the following month the American Barge Lines, operating entirely within Base Section Two, was assigned to that section.

The division of CBI on 24 October 1944 into the India–Burma and the China Theaters was effected without causing major reorganization of SOS. Advance Section One already had been granted virtual autonomy and became SOS in the China Theater. Transportation Service was little affected. Aside from providing several key rail, port, and inland waterway men requested by the China Theater, its personnel and functions remained unchanged.18

Developments in India–Burma Theater

When the India–Burma Theater came into being, most of the major transportation problems had been overcome or appeared susceptible of early solution. The once congested Calcutta port was now one of the world’s leading U.S. Army port installations. QUADRANT capacity targets for the Assam LOC were being exceeded, and supplies were flowing smoothly to the forward area thanks to centralized movement control, MRS operations, and American and British pipeline and other construction. The American barge equipment proved unsuitable for long hauls on the Brahmaputra, but proved useful in Calcutta port operations and for the support of airfields in east Bengal. Karachi, now a minor port, and the Bombay Port of Debarkation were operating efficiently.

There had also been good progress in the build-up of air deliveries to China and the prosecution of combat and construction operations in north Burma. The capture of the Myitkyina airfield in May 1944 had greatly improved air routes to China from India and, together with the increased flow of supplies into Assam, brought a spectacular rise in traffic over the Hump. In October 1944 Air Transport Command (ATC) and other carriers delivered 35,131 short tons to China, dwarfing the 8,632 short tons carried to China in October 1943.19 The town of Myitkyina fell to the Allies in August 1944 and was rapidly converted into a forward supply and air base. It appeared certain that the reopening of the land route to China would not be long delayed.

Transportation activities continued to expand into early 1945 as cargo arrivals were accelerated in support of developing airlift, construction, and combat operations. Traffic at Calcutta and along the Assam LOC increased, reaching a peak in March and April. Meanwhile, the long-awaited restoration of overland communications had been effected in January, and in the following month organized through-deliveries of vehicles over the Stilwell Road to China were begun.

By the late spring of 1945, transportation operations tended to level off and decline. To be sure, the build-up of China traffic continued from some time. Hump deliveries reached a peak of over 73,000 short tons in July; the four-inch pipeline extending along the Stilwell Road from Ledo to Kunming was opened in June; and China road deliveries were kept near peak levels through the middle of the year. Over-all traffic, however, declined as fighting in central Burma came to an end. Burma cargo deliveries fell off, MRS traffic declined, and cargo arrivals at Calcutta diminished. The port of Karachi was closed, and, at the request of the British, American troop debarkations were transferred from Bombay to Calcutta.

With the end of hostilities, shipments to India–Burma were sharply curtailed and all projects canceled. After clearing the supply routes to China, major wartime operations were speedily concluded. By the middle of October 1945 the MRS railway had been turned back to the British, Stilwell Road deliveries completed, and the American Barge Lines operation abandoned. Hump and pipeline deliveries were terminated shortly thereafter.

SOS had been inactivated in May 1945 and its responsibilities turned over to the

theater G-4, but the Transportation Service had retained its functions. In September 1945 General Rose left the theater and was succeeded by Col. A. C. Bigelow. On 8 October the Transportation Service was discontinued as a command and established as a special staff section, functioning primarily in an advisory capacity to G-3 and G-4 in theater headquarters on evacuation activities.20 Troop departures and the outloading of supplies and equipment were substantially completed by the end of April 1946, and in May the India–Burma Theater was inactivated.

Transportation in China Theater

The military situation in China was critical in the fall of 1944. The Japanese offensive, begun in the spring, threatened to engulf central and southwestern China. After taking Kweilin on 10 November, the Japanese seized Liuchow and Nanning. The only bright spot in the tactical picture was on the Salween front, where Chinese forces were clearing a path for the Burma Road engineers, who were pushing toward a junction with the Ledo Road.

Believing the enemy intended to take the vital Kunming air terminal, Maj. Gen. (later Lt. Gen.) Albert C. Wedemeyer, Stilwell’s successor in China, developed plans to deploy all available Sino-American forces for the defense of the area and most transport facilities were diverted toward that end. The threat to Kunming never materialized. After advancing within sixty miles of Kweiyang in early December, the Japanese offensive stalled.

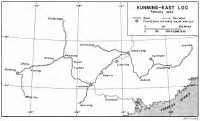

Although the Japanese failed to take Kunming, they had wreaked enormous havoc. The East Line of Communications (ELOC), extending eastward from Kunming to the advance airfields of the Fourteenth Air Force, had been cut in half. With the exception of Chihchiang, the eastern airfields had been captured or destroyed, and the standard-gauge railway lines had been taken, leaving only two short meter-gauge lines in Chinese hands. On the operable highway portions of the ELOC, freezing weather, hordes of refugees, and the deterioration of motor vehicles had reduced the movement of supplies to a trickle.

Throughout Free China, transportation facilities were hopelessly inadequate. The Chinese vehicles, in early 1944 reported on the verge of collapse, were now a year older, and the 544 U.S. Army trucks flown in between April and the end of December 1944 provided little relief. Vehicles, drivers, and maintenance personnel and facilities were lacking, road conditions were bad, and the lack of centralized control made for inefficient utilization of the battered and overworked transport.

The situation was so critical that General Wedemeyer on 13 December 1944 sent an emergency request to Somervell for the earliest possible delivery of 5,000 lend-lease trucks, already on order, even if it meant an increase in the China Theater’s allotment of ships. He also asked for the expedited shipment of 2,000 additional 2½-ton 6x6 U.S. Army trucks. In summarizing the transportation situation, Wedemeyer reported that the Chinese had only about 2,000 trucks in good condition and that the capacity of Chinese transport was rapidly declining. Wedemeyer’s requests were approved in Washington, and

immediate action was taken to deliver the trucks. This was followed by the establishment of a program to bring 15,000 vehicles to China by the end of 1945 and an additional 5,000 trucks shortly thereafter.21

The establishment of the China Theater was followed by a general elaboration of American and Chinese transportation organizations. Advance Section One became SOS U.S. Forces China Theater, and its principal transportation activities shifted from support of the eastern airfields of the Fourteenth Air Force to the supply and movement of U.S.-sponsored Chinese divisions, which had been designated by China to receive supplementary American training and equipment. SOS was charged with the responsibility for insuring the uninterrupted flow of supplies, equipment, and personnel to the U.S. Forces and to U.S.-sponsored Chinese forces. This responsibility extended from the bases where supplies were picked up to the forward truckheads where they were turned over to the American liaison officers with the Chinese combat commands. Within SOS, a Transportation Section coordinated and guided transportation operations, while area commands (later base sections) assumed an increasing degree of control over transportation operations.22

The Chinese set up a parallel supply service organization at Kunming in February 1945. The Chinese supply service was responsible for the supply and transport of Chinese military forces and operated under American SOS guidance. Meanwhile, a War Transport Board (WTB) had been established at Chungking in January as an agency of the Chinese National Military Council. The WTB, a Chinese organization with American liaison representation, was to exercise centralized control over all Chinese transportation. Liaison with this agency was an important function of Col. Lacey

V. Murrow, who was appointed theater chief of transportation in the same month. Heading a small special staff section at theater headquarters at Chungking, Mur-row engaged in planning activities and worked closely with WTB and other agencies in integrating American and Chinese transportation activities. The WTB was slow in assuming all its assigned functions, but as finally organized it proved a reasonably effective control agency.23

The turning point in the critical transportation situation came with the opening of the Stilwell Road. The flow of vehicles and drivers from India and Burma gave new life to motor transport operations. At the same time, the limited rail facilities were improved through Amer--

can technical advice and some material assistance, and inland water transport, heretofore restricted in development by the shortage of supplies and the need for fast delivery, was more fully exploited.

The increased delivery of supplies to China and the beginning of an improved transportation system within China brightened the tactical situation. In February 1945 the China Theater drew up a plan for offensive operations aimed at the ultimate seizure of the ports of Canton and Hong Kong. The opportunity to set the plan in motion came earlier than anticipated. After resuming the offensive in March and April 1945, the Japanese, apparently alarmed by the threat to the China coast posed by the Iwo Jima and Okinawa invasions and the possibility of Russian intervention, began to withdraw from south and central China. The Chinese followed and reoccupied the evacuated territory, retaking Nanzning, Liuchow, and Kweilin. With the occupation of these cities, motor transport routes were lengthened, inland water routes were established in liberated areas, and the possibility of rehabilitating recaptured standard-gauge railroads was explored.

In June 1945 Wedemeyer notified the War Department that Fort Bayard, a port on the Liuchow Peninsula could be taken by 1 August. This operation would open a new line of supply to China and provide a steppingstone for the capture of Canton and Hong Kong. Five loaded Liberty ships were readied at Manila for shipment to Fort Bayard, a program of highway construction and improvement got under way in the Liuchow area, and arrangements were made to transfer port companies from Calcutta. During this period, Hump, pipeline, and vehicle deliveries to China were at a peak, and within China a mounting volume of supplies moved to forward areas from Kunming, Chanyi, and other points of delivery. Motor transport operations continued to expand as additional trucks and drivers were assigned; rail traffic, although still small in volume, increased; and inland water deliveries were at their highest.

The Fort Bayard project was not carried out because of the end of hostilities and the opening of Shanghai. After completing the immediate postwar task of supporting the air deployment of Chinese troops to east China and clearing the pipe, air, and road supply lines to China, American wartime operations ended. By the end of the year, U.S. Army troops had been completely evacuated from west China and continuing postwar activities were confined to the Shanghai area.

The Indian Ports

When U.S. Army transportation operations began in CBI early in 1942, the ports available for American use were limited in number. The presence of Japanese forces within striking distance of the east coast of India prevented use of east coast ports. Bombay, on the west coast, was the main British port of entry and was heavily congested. Cochin was available, but unsuitable rail connections made its use inadvisable.

Karachi

Karachi, on the northwest coast of India, offered the most satisfactory service at the time, and it became the first port of entry for American cargo and personnel. Like other Indian ports, Karachi was administered by a civilian port trust created by and operating under the Government

of India. There were 22 ship berths, with maximum drafts varying from 10 to 30 feet, and 12 fixed moorings with drafts up to 30 feet. Large vessels could be moored two miles below the end of the wharves in 60 feet of water. There were adequate water and bunkering facilities, a limited number of floating cranes and lighters, and a few tugs and launches; all wharves were equipped with 1½-ton electric shore cranes. The wharves were rail served and most cargo was unloaded from ship to railway cars. Since there were no shipside or transit sheds, cargo was at once transported to warehouses by rail, truck, or lighter.

Upon the arrival of the first shipment of American troops in March 1942, Wheeler set up a provisional port detachment. Classification, sorting, and movement to storage areas of 20,000 long tons of China lend-lease cargo diverted from Singapore and Rangoon became the first duty of this group. These supplies had been received by the Karachi Port Trust and dumped on the docks without any attempt to classify and store them.24

The provisional detachment functioned until May, when its duties were taken over by the newly arrived headquarters and two companies of the 393rd Port Battalion, consisting of white officers and Negro enlisted men. With the move of SOS headquarters to New Delhi, port operations came under the direction of Base Section One. Under the section commander, the commanding officer of the port battalion was appointed port quartermaster, and junior officers were assigned to supervise water and port activities and to arrange for air and rail transportation.

During 1942 practically all equipment and supplies for CBI entered through the port of Karachi. Cargo handling was under American direction. The port troops supervised native coolie labor provided by stevedoring contractors and served as drivers, checkers, guards, crane operators, dock foremen, and riggers. Although the battalion had no stevedoring equipment upon arrival in India, it was gradually acquired or constructed by port personnel. Improvisation and on-the-job training resulted in a steady improvement of port operations. During the year, Karachi discharged a total of 130,342 long tons of cargo, loaded 8,065 long tons, and arranged for the rail shipment of 54,140 long tons to other parts of the theater. In addition, approximately 13,800 troops were debarked and 4,908 were shipped by rail to other sections.

Although U.S. Army and CDS tonnage arriving in the theater mounted steadily during 1943, incoming traffic at Karachi did not increase. As soon as the tactical situation permitted, an east coast port closer to the forward areas was opened. Beginning in September 1942, supplies were transshipped from Karachi to Calcutta. The latter was opened to vessels arriving from the United States in March 1943 and soon surpassed Karachi in importance.

With the shift of emphasis from Karachi to Calcutta, the two port companies were transferred, one moving to Calcutta in February 1943 and the other in August. Continuing port activities at Karachi were handled by a small Army staff supervising native labor. The loss of the port

units did not impair operational efficiency. During 1943 Karachi three times stood first among overseas ports in monthly cargo discharge performance, and in December set a new port record for itself, unloading 5,645 long tons from the SS Mark Hopkins in three days and ten hours working time.

Despite the designation of Karachi as the main delivery port for assembled aircraft, it handled a dwindling traffic in 1944. After January 1944 Karachi was unimportant as a supply base, except for the units in Base Section One. The major activity was the discharge of a monthly average of two ZEC-2 vessels carrying assembled aircraft. The port’s outstanding performance during the year was the discharge of the Mark Twain. This fully loaded cargo ship carrying 5,597 long tons was completely unloaded 48.5 hours after docking.

With the progressive withdrawal of personnel from western India, the need for an Army port organization at Karachi gradually disappeared. On 15 May 1945 Base Section One was officially inactivated, and with the exception of a small detachment that supervised the unloading of small shipments arriving on tankers and some coastwise cargo, all troops were transferred to other installations in the India–Burma and China theaters.25

After the termination of hostilities, Karachi became an important port for the evacuation of personnel from the theater. The Karachi Port of Embarkation was activated in August 1945, and in the following month a series of trans-India rail movements began that brought troops from the Ledo and Chabua areas to Karachi. As aircraft were withdrawn from the Hump run, they supplemented and later supplanted the troop trains.

Troops arriving at Karachi were billeted at the Replacement Depot at North Malir, fourteen miles from the port. After processing and as ships became available, personnel were trucked to shipside and embarked. The first troop transport to arrive, the General McRae, berthed on 22 September and took on 3,008 passengers. Evacuation operations reached a peak in October, when 26,352 troops were loaded on eight transports. The Army port at Karachi was closed in January 1946, having embarked 80,185 personnel, and all port troops were either transferred to Calcutta or returned to the United States.26

Bombay

Despite its magnificent deepwater harbor and excellent port facilities, Bombay was overtaxed by British and Indian traffic and remained so into 1943. As a result it was never used to handle much American cargo. However, since neither Karachi nor Calcutta could accommodate large transports, Bombay became the major port of debarkation for American troops entering CBI. During 1943 a total of 118,983 Americans passed through the port, including troops debarked and transshipped to the Persian Gulf Service Command.

During this period American operations were conducted by a small staff from Base Section One. Much of the work consisted of making the necessary arrangements with the British, who directed the debarkation of troops and the discharge of

cargo, provided berthing and staging facilities, and handled the onward rail movement. From Bombay the troops traveled 1,300 miles by rail to Calcutta and more than 2,100 miles to east Bengal or Assam.27

On 31 December 1943 the Bombay Port of Debarkation was established as an exempt station directly under the commanding general of Transportation Service. A port commander and a military staff were assigned and civilians were hired to supplement them. Subsequent accretions brought the number of port personnel to approximately 500. The port’s principal mission was the debarkation of U.S. Army troops, from transports usually berthed at Ballard Pier. It also handled the embarkation of U.S. and Allied military and civilian personnel leaving on American vessels and the unloading and transshipment of a limited amount of coastwise cargo.28

Although the U.S. port organization supervised the debarkation of American troops, the British at first retained control of all port installations, staging areas, and rail movements. Every action had to be cleared with the British authorities, an arrangement the Americans found unsatisfactory. They complained that debarkations were delayed by the provision of insufficient rolling stock and poor timing of trains scheduled to move troops from ship-side, and that the staging facilities were not up to American standards.

Gradually, one function after another was transferred, and eventually the U.S. port commander assumed responsibility for most activities pertaining to American operations, including the actual debarkation and embarkation of personnel, the loading of special trains, and the discharge and loading of cargo and organizational impedimenta. Reliance on British staging facilities ended in July 1944 when an American staging area was opened at Lake Beale, 125 miles from Bombay at one of the main trans-India railway connections. Camp Beale handled debarking and embarking personnel until October, when a section of Camp Kalyan, a British staging area at Bombay, was released to the U.S. Army and placed under the port commander. It was used to stage military and civilian personnel departing from the India–Burma theater. Camp Beale was then assigned to SOS Replacement Service and was used exclusively as a staging area for troops arriving in the theater.

Until the late spring of 1944, most U.S. Army troops arrived on British transports after transshipment from WSA vessels in the Mediterranean. Thereafter, they were brought in by U.S. Navy transports of the P-2 type. The first of these, the General Butner, arrived in May, followed in July by the General Randall. On the basis of the experience gained in handling these two vessels, the port staff was reorganized and operating procedures were modified.

By the latter part of 1944 the Bombay port operation was proceeding satisfactorily. Although the problem of timing the arrival of troop trains at quayside persisted, there was a steady improvement. Debarkation procedures were established to insure a five-day turnaround for the ships, although the wait for convoy escorts

occasionally extended the time to seven days.

American operations were brought to a close when the British expressed their desire to secure the exclusive use of Bombay for anticipated post-V-E Day redeployment of their troops to India. After a successful experimental run of two smaller American transports to Calcutta in February 1945, it was decided to give up the west coast port. The last transport to arrive at Bombay, the Admiral Benson, berthed late in March, unloading 4,866 troops and taking on 1,363 passengers. All debarkation activities were then shifted to Calcutta, and on 1 June Bombay was officially closed as an American port.

Calcutta

Calcutta is located in Bengal, eighty miles up the Hooghly River. The stream followed a winding course and was relatively shallow, accommodating ships with a draft of 22 to 30 feet, depending on the season. The port had a total of 49 berths, most of which could accommodate oceangoing vessels, and 44 ships could be anchored in the stream. The more modern of these facilities, the King George and the Kiddepore Docks, were inside the tidal locks. Most wharves were equipped with transit sheds, and there was a fair amount of shore and floating equipment. The port was served by three broad-gauge rail lines, the Bengal and Assam Railway having tracks into the docks. The labor supply was ample.

Although Calcutta by virtue of its location and facilities was more desirable than the west coast ports, Japanese activity in the Bay of Bengal initially barred its use. Beginning in September 1942, however, supplies were transshipped by water from Karachi to Calcutta, and by the end of the year six small vessels had been discharged under the supervision of an Engineer unit that had been detailed to the task. Enemy action did not seriously hamper port operations, although an air raid in December 1942 caused a large-scale civilian evacuation and produced a temporary labor shortage. Later raids in January and December 1943 had little effect on port activities.29

Port operations began to expand when, upon the recommendation of the Anglo-American Shipping Mission, shipping was routed directly from the United States to Calcutta. About 8,000 long tons of U.S. Army and China-aid supplies arrived in March 1943, and incoming tonnage mounted steadily thereafter. Under the command of Base Section Two, the two port companies transferred from Karachi, the 540th and 541st, took over supervision of U.S. longshore and dock operations. U.S. Army port activities tended to be centered at the King George Docks, although some cargo was discharged at the Kiddepore Docks or, in the case of heavy items such as steel, at berths outside the tidal locks.

The port troops supervised coolie labor, checked and sorted cargo, prepared tallies, and loaded cargo into trucks, barges, and rail wagons for transshipment to the proper consignees. In an effort to unload maximum tonnages, they operated in twelve-hour shifts and often worked as long as eighteen hours at a stretch. The

port troops trained Indians in cargo checking and the operation of mechanical equipment. To counteract the acute officer shortage, noncommissioned officers were assigned to many responsible positions.30

These measures substantially increased cargo discharge, but not enough to keep up with incoming tonnage. There were insufficient port personnel and equipment, centralized direction of military and civilian activities was lacking, and ships arriving from Colombo, Ceylon, were bunched in convoys and were delayed from three to ten days awaiting berths. At the same time, the inability of the Assam LOC to lift the cargo landed caused an accumulation of freight at the docks, warehouses, and sheds. The developing congestion at Calcutta in the latter part of 1943 threatened to handicap current and projected operations, and in December Covell termed the port “our No. 1 problem.”31

The first solid relief came in late December 1943 and early January 1944 when two port battalions, the 497th and 408th, including headquarters and headquarters companies and a total of eight port companies, arrived at Calcutta. The organizations were accompanied by cargo-handling equipment and possessed a number of experienced officers and enlisted men. The two battalions began operations at the King George Docks, where they handled all U.S. Army transports. The 540th and 541st Port Companies were then moved to the Kiddepore Docks and the Calcutta Jetties, where they supervised the discharge of commercial vessels and animal ships.

As the new port troops tackled the job of clearing the congestion at Calcutta, steps were being taken to facilitate their task. Arrangements were made to discontinue convoys from Colombo temporarily in order to relieve pressure on Calcutta; Madras was opened as a subport to which overflow cargo could be diverted from Calcutta; British agreement was obtained to appoint a port controller for Calcutta; and, effective 1 March 1944, the King George Docks, with four general cargo berths, completely equipped sheds, shore cranes, and a fifth berth under construction, were leased for the exclusive use of the U.S. Army.32

The importation of port troops and equipment and other measures taken to relieve congestion had their desired effect. Tonnage discharged monthly at the port more than doubled in January 1944, and in February totaled 128,397 long tons, a record for the year. By the middle of March, the base section commander was able to report that the bottleneck at Calcutta had been broken. With the British port controller finally arrived in May, the port was operating smoothly. As a result of improved methods and the better spacing of ship arrivals at Calcutta, the maximum time lost by any vessel waiting for a berth between June and October was one day. During this period the port units, spurred on by friendly competition, steadily improved their operations, and unloading activities were further facilitated when American barge equipment and low-bed trailers and tractors were received.33 As will be seen, the Assam LOC’s increased ability to move supplies forward was also

an important factor in making port operations more fluid.

During 1944 Calcutta handled most of the U.S. Army and CDS cargo arriving in the theater. In that year the port discharged 1,092,625 long tons, while Karachi unloaded less than 100,000 long tons. As the theater’s major cargo port, Calcutta played an important role in making CBI the leader in port discharge performance. After February 1944 the theater, with few exceptions, stood first among the overseas commands in the rate of discharge. Calcutta, however, had a number of advantages. With the exception of a few air raids, all of them before January 1944, the port did not operate under combat conditions; a large supply of native labor was available; and the U.S. Army controlled a modern, well-equipped dock area. These factors, together with the performance at Karachi, which handled a relatively small amount of “easy” cargo, helped keep the theater in the number one spot.

Increased cargo arrivals, beginning in November 1944, resulted in further expansion of port activities.34 Discharge operations reached their peak in March 1945, when 173,441 long tons were discharged from 66 vessels. This increased traffic was handled without increases in men or machinery. Operating under the Water Division of Base Section Two, the port troops had developed standardized operational procedures and were now seasoned veterans. Discharge activities were conducted twenty-four hours a day, the port personnel supervising native labor in the hatches and on the docks. Arrangements had been made with contractors to supply the same coolies each day, thereby permitting them to develop skills on the job. The Army men checked cargo, super vised the loading of freight cars, and operated all floating cranes and other cargo-handling equipment. The system of competition between units was retained and intensified, and wherever possible cargo was unloaded directly from shipside into rail wagons, barges, and trucks for movement to depots or direct to forward destinations.

Monthly cargo arrivals fell off after March 1945, although they were still greater than during most of 1944. With the exception of a brief period of congestion beginning in May, when a large number of British and foreign flag vessels were brought into the port in preparation for the Rangoon operation, cargo was handled expeditiously and the average cargo vessel was discharged in three days. As the sole cargo port in the command after Karachi closed, Calcutta continued to function smoothly. Port troops and native labor, working at five berths at the King George Docks, discharged an average of 122,549 long tons a month from June through September 1945, and in July established a new theater record, discharging 3,034 measurement tons and releasing the Alden Besse in thirty hours.

The port also continued to load some coastwise cargo and handled a limited amount of export shipping to the United States, loading such items as repairable airplane engines and salvage. The one large loading operation before the end of hostilities was the transfer of personnel and equipment of the XX Bomber Command to the Pacific Ocean Areas. The

movement, effected between May and July 1945, involved the water shipment of 10,257 men and the loading of 10 cargo ships with 13,932 long tons of cargo, including 2,291 special and general type vehicles.

Meanwhile, Calcutta had taken over the theater’s debarkation and embarkation activities. After the successful experimental run of two C-4 transports into Calcutta in February 1945, the Bombay Port of Debarkation was closed and key personnel were transferred to Calcutta, where they organized an Embarkation and Debarkation (E&D) Section under the base transportation officer. Liaison was established with U.S. Navy and British port authorities, and plans were made for handling troop transports. The first two regularly scheduled C-4’s arrived at Calcutta on 27 April 1945 and anchored in the stream. Under the supervision of the E&D Section, 5,762 debarking troops were ferried to Princep Ghat, where they were loaded on special trains arranged for with British Movements. Embarking troops were then ferried to the ships and were all aboard on 6 May.

Procedures were improved as successive troopships arrived. However, selection of Shalimar Siding for embarkation proved unfortunate, since troops had to carry their duffle bags one quarter of a mile in the heat over railroad ties before reaching the ferry. After the first regular operation, Princep Ghat was used for both embarkation and debarkation. Another improvement was put in hand when experiments proved that the transports could come aside the jetties and deliver personnel directly to shore without the use of ferries. To deal with delays in obtaining trains, troops were moved by river steamer from Princep Ghat to Kanchrapara staging

area, the temporary destination of most troops. Later, movements to and from Kanchrapara were made by truck. In the closing months of the war, as backlogs of high-point, rotational, and other personnel awaiting departure by water began to develop, efforts were made to ship troops aboard cargo vessels as well as troop transports. From 20 May to 2 September 1945, a total of 17,666 troops embarked at Calcutta, while 16,028 debarked.

With the termination of hostilities, the flow of traffic into Calcutta was rapidly reversed. Eleven of twenty-nine ships en route to the India–Burma theater were returned to the United States and three were diverted to Shanghai.35 Cargo and troop arrivals at Calcutta declined sharply in September and were negligible thereafter. At the same time personnel being evacuated from China and all parts of India and Burma began moving into the Calcutta area, and programs were formulated to ship supplies accumulated or backhauled to the port.

The principal postwar cargo operations involved the shipment of POL and general cargo to the newly opened port of Shanghai, the dumping at sea of deteriorating ammunition and chemical warfare toxics, and the return to the United States of materials not otherwise disposed of in the theater. Vessels for these purposes were allocated by the War Department. Loadings were performed exclusively by the U.S. Army port organization until late 1945, when personnel losses caused the Americans to arrange for the assistance of commercial shipping agents. By the end of February 1946, as the shipping program neared completion, most of the facilities at the King George Docks were returned to

the Calcutta Port Trust. The last port company was inactivated on 19 April, and the port was then operated on a purely commercial basis. From the beginning of October 1945 through April 1946, a total of 320,437 long tons was shipped to the United States, Shanghai, or other overseas areas, and 73,547 long tons of ammunition and toxic gas were dumped. With the exception of minor tonnages loaded at Karachi for Shanghai in October 1945, all loadings were made out of Calcutta.36

In the meantime, Calcutta had joined Karachi in effecting the water evacuation of troops. The first ship under the postwar program, the General Black, arrived on 26 September 1945 and took on 3,005 passengers. Subsequent arrivals were either other C-4 “General” troopships or smaller War Shipping Administration “Marine” vessels, capable of carrying about 2,500 passengers. Transports were generally berthed at Princep Ghat or the Man-of-War Mooring. Embarkation activities at Calcutta reached a peak in November, when 21,990 embarked on eight transports. The closing of Karachi in January 1946 kept Calcutta busy for another month, but activities fell off as evacuation approached completion. By the end of April, 187,761 troops had departed the theater by water. Of these, 107,576 left from Calcutta. The final embarkation operation of the India–Burma Theater took place on 30 May, when 812 military and civilian passengers boarded the Marine Jumper.37

Madras and Colombo

Used at first as an emergency port to lighten vessels whose draft did not permit entrance into the Hooghly River, Madras was opened as a subport of Calcutta in February 1944 to handle overflow ship- ping. After discharging a total of 24,363 long tons in February and March, the port received only minor tonnages. With the clearing of congestion at Calcutta, the port’s activities were limited to the lightening of vessels and the discharge of small coastwise shipments for the supply of U.S. Army detachments and a small Army drum plant located in the vicinity. A small transportation staff was retained at Madras to expedite transfer of port operations in the event Calcutta should be rendered inaccessible.

Another minor American port operation was established following the transfer of Southeast Asia Command headquarters from New Delhi to Kandy, Ceylon. A Transportation Service officer was stationed at Colombo in April 1944 to act as port transportation officer and to maintain liaison with SEAC and the Eastern Fleet. Aside from his liaison functions, the officer’s principal activity involved supervision of the discharge of cargo for the supply of the small group of U.S. Army personnel serving with SEAC. By October 1945 cargo arrivals had ceased, and all that remained to be accomplished was the shipment of some surplus supplies to Calcutta.38

The Assam Line of Communications

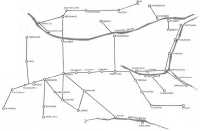

The transportation system leading from Calcutta into Assam, called the Assam

LOC, was described by one Army observer as “the most fascinating and complex problem we have in the world.”39 (Map 9) It consisted of rail, water, rail/ water, water/rail, and to a limited extent rail/highway routes.

The Bengal and Assam Railway, a state-owned line controlled by a civilian railway board, was the main carrier on the LOC. Supplies were shipped from Calcutta over a broad-gauge line 200 and 275 miles respectively to Santahar and Parbatipur, the principal points for transfer from broad-gauge to meter-gauge railroads. At these stations freight was transferred to the meter-gauge line, which cut across the broad-gauge line from the west. The rail wagons were moved to the Brahmaputra River where they were ferried across, and then they proceeded to Tinsukia, whence they traveled over the short meter-gauge Dibru–Sadiya Railway to Ledo, 576 miles from Parbatipur.

The railroads were supplemented by two civilian steamship lines, which hauled supplies approximately 1,100 miles up the Brahmaputra from Calcutta to Dibrugarh in Assam. The river and rail systems were closely intertwined, and there were numerous junctions along the route where supplies might be shipped by rail to Goalundo, barged to Dhubri or Neamati, and thence hauled by rail to final destination.

There was no all-weather through highway from Calcutta to Assam. A motor road, however, did extend eastward from Siliguri, at the northern terminus of the Bengal and Assam Railway, through Bongaigaon to Jogighopa. From this point vehicles could be ferried across the Brahmaputra and then proceed over the Assam Trunk Road to Chabua and Ledo. Late in 1943, a limited convoy operation was being conducted by Intermediate Section Two from Bongaigaon to Chabua.

The LOC was ill-prepared to take on wartime traffic. Part of the broad-gauge rail line and most of the meter-gauge line were single tracked. The meter-gauge line in particular was a bottleneck: there were no bridges across the Brahmaputra; the steep gradient at the eastern end of the line made travel slow and hazardous; and monsoon rains annually disrupted service by washing out rail lines and damaging rail bridges across smaller rivers such as the Beki. To add to these difficulties, the Bengal and Assam Railway was called upon to handle increasing traffic with little additional equipment; lacking replacements and proper maintenance, rail equipment deteriorated. Like the railways, the inland waterway lines were subject to disruption during the monsoons, and, in addition, their operation was slow and restricted during low-water periods.40

At the outbreak of war, the Assam LOC carried only about 1,000 to 1,500 long tons daily. In an effort to increase its capacity to support developing military activities in northeastern India, military movement control was gradually introduced, although operation of the carriers remained in the civilian hands. In March 1943 the British established a Regional Priorities Committee to allot military and civilian traffic in the Assam area. By October the capmity for military traffic had been increased to 2,800 long tons a day, but this was inadequate to cope with the supplies poured into the LOC.

During this period, the British also formulated plans to develop the LOC

Map 9: Assam Line of Communications

through new construction. Projects undertaken in 1943 included construction of double-track, railway sidings, yards, and a railway bridge over the Brahmaputra. Progress was slow, however, and few of the jobs were completed during the year.41

The LOC’s inability to lift the military supplies laid down at Calcutta became increasingly evident in the latter half of 1943. The port was congested with accumulated cargo. Supplies forwarded to Assam required up to fifty-five days for delivery, and it was not uncommon for shipments to be held more than thirty days on river barges. As the year ended, the theater G-4 reported that congestion on the LOC had reached serious proportions.

The tie-up on the Assam LOC was a matter of vital interest to the U.S. Army, then engaged in expanding construction and airlift operations in Assam and about to launch a campaign in north Burma. The American participation in QUADRANT planning for the LOC and the arrangements for the use of American railway troops have already been discussed. In addition, Covell, Wilson, and other interested officers in early 1944 pressed the British to militarize transport on the LOC completely. After negotiations, a compromise in February 1944 resulted in a system of semimilitary control in which the Americans participated.42

Under this system, the British deputy director of movements, assisted by a U.S. Army representative and in consultation with the railway and river transportation carriers, periodically estimated the total capacity of the LOC. Tonnage was then allotted for British and American military needs, essential civil requirements, and railway construction and maintenance. A LOC panel sitting in Calcutta implemented the allotments and controlled day-by-day operation. The Calcutta panel was headed by the deputy director of movements and consisted of representatives of the British regional controller of priorities (Calcutta North), the commanding general of the U.S. Army SOS in the theater, the Bengal and Assam Railway, the two commercial steamship companies, U.S. Military Railway Service, and British Movements Control. Although there was American representation on the panel and, beginning in March 1944, the Americans operated a portion of the meter-gauge railway, over-all control of the LOC remained in the hands of the British. However, despite inevitable differences of opinion between British and American authorities, a remarkable cooperation was maintained.

The primary function of the Calcutta panel was to coordinate the transport facilities on the LOC effectively. In addition to implementing tonnage allotments, the panel regulated traffic, issuing orders regarding the routes to be followed, the terminals to be used, the means of transport to be employed, and other operational practices. The panel ordered diversions from congested stations and when necessary ordered the complete or partial suspension of movements at points of origin until congestion was eliminated. In exercising its control, the panel early adopted the policy of reducing the length of the rail haul and increasing the use of river craft. The more rapid train turnaround

that resulted, together with the maximum use of the river lines, produced an over-all increase in tonnage moved.43

The centralization of traffic control was accompanied by other improvements. The British built new river ghats (landing stages) at river-rail junctions, provided additional labor and supervisory personnel, and augmented cargo-handling equipment at important rail and river transshipment points. Although rail construction lagged, some progress was made in double-tracking and in constructing passing tracks. Another major development in 1944 was the construction of pipelines. In March the British completed the Chandranathpur–Manipur Road (Dimapur) sector of a four-inch pipeline that ultimately was extended from Chittagong, India, to Tamu, Burma, and in August the Americans completed construction of a six-inch line from Calcutta to Tinsukia, Assam. These new facilities eased the burden on the hard-pressed railway and greatly increased the capacity of the Assam LOC.

Playing a vital part in the LOC’s development was the transfer to U.S. Army control of the meter-gauge line from Katihar to Ledo, a portion of the LOC long considered a major obstacle to accelerated movement of supplies to Assam. American operations brought an immediate speedup of traffic and gave a pronounced impetus to the entire project.44

The various improvements brought an immediate and sustained increase in traffic. What had been the major transportation problem in March 1944 was being “licked” in May. On 15 July Wilson was able to inform Somervell that the QUADRANT target for LOC tonnage set for January 1946 already had been exceeded, exclusive of pipelines. Performance was not up to capacity only because sufficient supplies were unavailable for shipment. In the ensuing months American and British tonnage shipped by rail, river, and pipeline increased steadily.45

When the India–Burma Theater was created in October 1944, the Assam LOC was no longer a major problem in the movement of supplies to the forward areas. U.S. and British military shipments had increased from 112,500 long tons in March 1944 to 209,748 long tons in October. To be sure, there was some difficulty in handling heavy lifts at transshipment points and in meeting the ever-increasing demand for petroleum products from the east Bengal and Assam airfields, but in general shipments were being made promptly. There was confidence that the LOC would be able to handle expeditiously “anything now planned or expected.”46

Traffic mounted steadily into the spring of 1945. The QUADRANT target for capacity, including pipelines, was reached in January, although operation to capacity never proved necessary. In March a record 274,121 long tons of U.S. and British military supplies were shipped by river,

rail, and pipeline. Although total tonnage decreased slightly in April, the daily average tonnage dispatched over the LOC reached a peak of 8,975 long tons.

During this period control by the Calcutta panel was increasingly effective, the Military Railway Service continued to step up its operations, and there was continued expansion of physical facilities. British track construction work on the broad-gauge and meter-gauge lines was continued, rail yards were improved, and additional cargo-handling equipment was provided at transshipment points. The largest new addition to the physical plant of the Assam LOC came in March 1945 with the completion of the American six-inch pipeline from Chittagong to Tinsukia. The new pipeline augmented deliveries by the Calcutta–Tinsukia pipeline and the rail and river carriers. Together, they provided gasoline and other petroleum products needed for Hump deliveries, filled the U.S. pipelines extending from Tinsukia into Burma toward China, and supplied fuel for the operation of vehicles on the Stilwell Road.

Tonnage movement over the LOC fell off after April 1945, when the central Burma campaign came to an end. As Chinese, American, and British combat and supporting forces withdrew, the demand for supplies in the forward areas lessened. The decline in this traffic, however, was partially offset by the acceleration of deliveries to China. The demand for POL, needed for air, truck, and pipeline operations, was particularly heavy, and amounted to 135,796 long tons in August.

Traffic moving forward on the LOC dropped sharply with the termination of hostilities and soon dwindled to minor proportions. The backhaul of supplies to Calcutta was well within the capabilities of peacetime transportation agencies. The Calcutta panel was discontinued on 1 October, and by the middle of that month American railway troops had been removed from the MRS-operated line. Backhaul operations, involving the movement of 141,512 long tons of American materials from Assam and east Bengal, were completed in February 1946.47

The Military Railway Service in India–Burma

The use of American railway troops on the bottleneck meter-gauge rail portion of the Assam LOC, a proposal made by Somervell at the October 1943 intercommand meeting, was approved in principle by the Government of India. The final agreement, reached in February 1944, provided that effective 1 March the U.S. Army would operate 804 miles of meter-gauge railroad, consisting of the main Bengal and Assam Railway line from Katihar eastward to Tinsukia, branch lines from Dhubri and from Neamati and from Furkating to Jorhat, and the short Dibru–Sadiya meter-gauge line, which met the Bengal and Assam Railway at Tinsukia to complete the rail link to Ledo.

In general, the agreement provided for the substitution of military for civilian management and the augmentation of the civilian staff by military personnel. Commercial work was to be the sole responsibility of the Bengal and Assam Railway, which was also to provide all normal consumable stores. The general manager of the railway retained nominal control over

the American-operated line, but in practice did not interfere in methods of operation or assignment of staff. Movements remained under British Movements Control, and British construction proceeded as before.48

In December 1943, before the final agreement, the SOS had established a Military Railway Service headquarters at Gauhati under Col. John A. Appleton, former Chief of the Rail Division, Office Chief of Transportation. In January a railway grand division, five railway operating battalions, and a railway shop battalion arrived. The units moved to assigned positions along the line during the latter part of the month and prepared to begin operations.

Taking Over the Bengal and Assam

The MRS took over the railroad on 1 March without interference to traffic, superimposing some 4,200 troops on the existing civilian staff of 13,000. The 705th Railway Grand Division was stationed about midway on the line at Gauhati. The 758th Railway Shop Battalion moved into the railway shops at Saidpur, a few miles north of Parbatipur, and sent a detachment to Dibrugarh, near the eastern end of the line. The railway operating battalions each controlled a division of the line, the sectors varying between 111 and 175 miles in length. Three Bengal and Assam Railway officials were assigned to each headquarters to advise battalion commanders and handle the civilian staff.49

From the beginning, it was evident that planned expansion of physical facilities would not immediately expand the railroad’s capacity. The British had instituted a program to double-track the line, including the section between Lumding and Manipur Road, which because of its steep gradient was a limiting factor in movement over the entire Assam LOC. Plans were also made to break the other major bottleneck by replacing the Brahmaputra River Pandu–Amingaon Ferry with a bridge. However, no major rail construction was expected to be completed before August 1944, and plans for the rail bridge, scheduled for completion in two years, were dropped because of the time involved.

If an immediate increase in traffic was to be achieved, MRS would have to rely on operational improvements. This Appleton did. Abandoning the previous practice of maintaining a fixed debit balance of wagons owed to neighboring lines, Appleton forced the loading of the maximum number of wagons at Parbatipur and moved them to points of unloading. This measure inevitably resulted in a large increase in the number of wagons on loan from other lines and brought British criticism to the effect that the absorption of borrowed wagons into the MRS railway was impeding essential supply movements programed by the Government of India. When the cycle of return movements of empties caught up with dispatches, however, the drain on adjoining lines diminished, and the problem ceased to be serious. Another innovation was the operation of longer trains in order to

compensate for the motive power shortage and to increase tonnage movement without increasing traffic density. Also, movements across the Brahmaputra River from Amingaon to Pandu were stepped up by using two locomotives simultaneously on each of the two ferries to move freight wagons, and by increasing crews at the river ghats.50

As a result of these improvements, overall eastbound traffic in March increased 31 percent over February, and deliveries to the forward areas at Manipur Road, Chabua, and Ledo were increased 44.6 percent, only 5.4 percent below Somervell’s prediction. One surprising result of this rapid development was that the meter-gauge railway was actually hauling more tonnage from Parbatipur than the 233-mile broad-gauge system running north from Calcutta could provide. Remedial measures by the British eventually brought this problem under control.