Chapter 12: At El Alamein Under Auchinleck

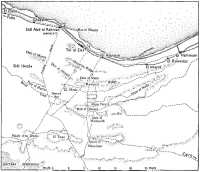

On 30th June Rommel’s army was pressing on towards the last British defences west of the Nile Delta – the partly-prepared El Alamein position which obstructed the 30-mile neck of desert between the sea near El Alamein and the Qattara Depression. For some days troops allotted to its defence had been digging, wiring and laying mines while past them poured the transport of a retreating army.

A system of fortified locations had been laid out there and partly constructed in the months preceding the launching of the CRUSADER operation. The most developed stronghold provided all round defence for an area surrounding the El Alamein railway station and extending from the coast across the main road and railway and south into the desert for a few miles.

North of El Alamein railway station the coast road travelled along a low rise which lay between the railway and the narrow strip of salt marsh and sand dunes bordering the sea. To the immediate south only two noteworthy features emerged from a slightly undulant waste of sandy desert: the low ridges of Miteiriya and Ruweisat. South of Ruweisat the desert floor became rougher and was broken by sharp-edged escarpments and flat-topped hills nowhere rising to more than 700 feet. Cliffs defined the southern border of the desert tract on which the Eighth Army had chosen to stand; below them lay the waterlogged Qattara Depression, deceptively covered with a brittle sun-baked sand crust. South of the Qattara Depression, which could be bypassed only far to the west, and then only by going far to the south, stretched the soft and shifting sands of the Sahara, impassable by conventional military vehicles.

The plan for defending the El Alamein positions had long provided for three defended areas, or “boxes” to use the terminology then current, one about El Alamein, one about Bab el Qattara about 15 miles to the south and a third round Naqb Abu Dweis at the edge of the depression. The El Alamein Box had been dug and partly wired and mined; the Bab el Qattara position had been dug but not mined; at Naqb Abu Dweis little work had been done. Each box lay astride one of the three main lines of approach from the west: the El Alamein Box was astride the main road and railway, the Qattara Box astride the Barrel track leading from Fuka to the Cairo-Alexandria road, and the Naqb Abu Dweis Box astride passable country along the escarpment north of the Qattara Depression.

In the month since Field Marshal Rommel’s offensive had opened, the strength of the Eighth Army had been drastically whittled away. When Rommel attacked at Gazala it had comprised two armoured divisions (1st and 7th), four infantry divisions (1st and 2nd South African, 5th Indian and 50th British), and the 1st and 32nd Army Tank Brigades; the 10th Indian Division, 1st Armoured Brigade and 11th Indian Brigade were under orders to join it. On 1st July the army possessed only one complete

El Alamein

infantry division (the 2nd New Zealand1), one depleted infantry division (1st South African), one fairly effective armoured division (the 1st), two brigade groups (9th and 18th Indian), and numbers of battle groups or columns formed from the 7th Armoured and 5th Indian and 50th British Divisions. One complete and rested infantry division was on the way forward – the 9th Australian.

On 1st July the 1st South African Division was on the right of the British line with its 3rd Brigade occupying the El Alamein Box. The 18th Indian Brigade, newly arrived from Iraq, and under command of the 1st South African Division, was about Deir el Shein. The 1st Armoured Division was deployed between the El Alamein defences and the eastern end of Ruweisat Ridge. In the XIII Corps area to the south the 6th New Zealand Brigade was forward of Bab el Qattara with the remainder of the division some 10 miles to the east. The 5th Indian Division with one brigade – the 9th – was at Naqb Abu Dweis and the 7th Motor Brigade between it and the 6th New Zealand with patrols forward.

General Holmes’ X Corps headquarters had been sent back on 30th June to command Delta Force, which was being formed to defend Alexandria and the western edge of the Delta should the forward positions be lost. It was to Delta Force that the 9th Australian Division had just been allotted.

The 9th Division, the only battle-hardened formation at General Auchinleck’s disposal that was thoroughly rested, was over-strength in men but gravely short of equipment. It was deficient in transport; the tanks of the cavalry regiment were obsolete and 22 below the establishment; only one field regiment had all its vehicles; only one anti-tank battery had 2-pounders, and there were no 6-pounders.

General Morshead, with Colonel H. Wells, his senior staff officer, arrived at Cairo on 28th June, reported to G.H.Q. for orders and was there given the task of defending the Cairo sector of the Delta with his division and some local bodies capable of combat in emergency, such as the Officer Cadet Training Unit. Morshead next reported to the headquarters of British Troops in Egypt and sought the written plans for the defence but, as these could not be immediately located, made a personal reconnaissance and that night issued preliminary orders from the map.

In Henry Wells, Morshead had been allotted a worthy successor to Lloyd, who had been his chief of staff in Tobruk. When appointed to the AIF in 1940 Wells had 20 years of varied staff service behind him and had passed the staff college in the company of British officers beside whom he was now serving. He had demonstrated his energy and efficiency on the staff of I Corps throughout the operations in Greece and Syria. He had joined Morshead a few weeks after the withdrawal from Tobruk and they had now been together for about seven months.

It is interesting to note that on 29th June, after a busy day preparing plans, Morshead spent the night at the home of Mr R. G. Casey, British Resident Minister in the Middle East. The part in Middle East affairs played at this period by Casey, a notable Australian parliamentarian accorded Cabinet status by the British Government, belongs more to British war history than Australian. It must suffice to mention here that in addition to exercising responsibilities in relation to civil affairs and to the Middle East Supply Centre, which coordinated the administration and distribution of both military and civilian supplies, he was brought into consultation whenever the military situation in the Middle East seemed so critical as to have political implications. At a later stage, for example, we shall find him visiting General Montgomery’s headquarters ‘during the battle of El Alamein at a time when the British Government became restive at Montgomery’s failure to achieve an early break-through. General de Guingand, referring to Casey’s role in Auchinleck’s time, wrote later:–

I felt that Auchinleck did not make the best use of the Minister of State. I believe he thought, possibly unconsciously, that the politician was critical of his handling of the situation. It was a pity, because Casey was out to help, and would have responded wholeheartedly to the full confidence of the Commander-in-Chief.2

At a conference at G.H.Q. on 30th June Morshead received orders cancelling the division’s role as last-ditch defenders of Cairo and directing it to go at once to Alexandria. Meanwhile G.H.Q. had sent orders direct to Brigadier Tovell to take his 26th Brigade Group to Amiriya. These orders reached Tovell before he had received Morshead’s earlier orders about the defence of Cairo.

These were the days of what later became known as the “Cairo flap”, a widespread apprehensiveness that followed warning orders to headquarters in the Cairo and Delta district to prepare for a move and the hurried departure of the fleet from Alexandria. General de Guingand and others later wrote of the alarm and despondency caused by the burning of voluminous documents and records.3 The warning orders have usually been represented as precautionary only. Morshead’s diary notes of the conference on 30th June suggest that at that time the possibility of a move of Middle East Headquarters was not so unlikely.

Conference at GHQ. Owing to withdrawal to El Alamein line and attacks on it by Rommel, plans made for the defence of the Delta and Cairo, and for moving of GHQ eastwards. 9 Aust Div ordered to Alexandria forthwith. Holmes appointed command Delta Force but as doubt whether he was captured or not I was appointed in event his not arriving.

General Holmes did arrive and was given the command.

The division’s move to Alexandria was described in its report:–

It was a journey that few will forget. The opposing traffic moved nose to tail in one continuous stream of tanks, guns, armoured cars and trucks or jammed sometimes for hours, holding up the divisional convoys at the same time. One block alone lasted from 0400 hrs to 0900 hrs on 1 July but fortunately no enemy aircraft attacked.

The historian of an artillery regiment thus described the journey:–

Congestion on the Desert Highway that night considerably hampered the progress of the guns, going up. There were long delays, accidents owing to bad visibility. To clear the road-blocks, lame ducks had to be pushed off the bridge of bitumen into the yielding sand. Sometimes the retreating columns were not only nose-to-tail, but two and three abreast. All their personnel except the drivers – and often the drivers, too – slept where they sat. There were bits and pieces of broken units – here and there an anti-tank gun, here and there a Bofors, here and there a 25-pounder.4

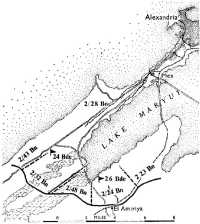

On 1st July Morshead left Cairo at 2 a.m., arrived at Amiriya at 8 a.m. and established his headquarters first at El Mex, “but being unventilated caves and funkholes moved to camp at Sidi Bishr – an awful place”.5 He then gave to the two leading brigades, just arrived, their precise tasks of denying the enemy the approaches to Alexandria from the west and south-west. The 24th Brigade was to occupy the right sector with its flank on the coast and the 26th Brigade was to be on the left. The 24th Brigade

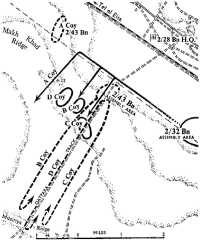

Dispositions, 24th and 26th Brigades, 1st July

(Brigadier Godfrey) took under command a motley force that had been assembled in its area, comprising the remnants of the headquarters of the 150th Brigade, the 1st Northumberland Fusiliers (the machine-gun battalion that had been part of the Tobruk garrison in 1941), and 600 troops from five units, including 120 Czechs and 30 naval men. Some land-based naval guns were to be used for anti-tank defence. The brigade was to hold a line constructed by the Polish Brigade in 1940 and 1941 to cover the isthmus north of Lake Maryut. Its three battalions occupied the line on the 1st. By the 2nd the 26th Brigade too was in position, and all units were digging busily. The 2/48th Battalion recorded that its men were working in relays, some digging while others slept; and that, in common with other units round Amiriya, it was completing its war establishment in weapons and other gear by salvaging large quantities of equipment left there by previous occupants.

Morshead spent 2nd July in reconnoitring with Brigadier Tovell, Brigadier Godfrey and Colonel Wells the areas his two brigades had been ordered to defend. He was disconcerted at the preparations so far made and determined that civilian considerations were not to interfere with the establishment of proper defensive positions in a warlike manner. The ground to be held was too extensive for the troops available, but could be reduced by flooding, which would interfere with the local salt industry. Morshead set the engineers channelling to let the sea in and sought Corps approval, but the situation at the front became more stable before it was necessary to press the point. Morshead’s notes on his visits to the 24th and 26th Brigades on 2nd July indicate that his orders included the removal of all civilians from the areas taken up, the discontinuance of any works being done by Egyptians, the clearing of fields of fire by cutting down palm trees and fig trees in the areas, and the demolition of a building.

Although General Auchinleck hoped to halt the enemy advance at El Alamein, he was also determined, come what may, to keep his army in being. If the El Alamein area was lost he would fight farther back on the approaches to the Delta. If these were lost he would fight on the Suez Canal with part of his force while part withdrew along the Nile. Plans

were prudently made for such operations. Inevitably they became known to some, and subtly affected their morale.

Among Auchinleck’s subordinate commanders there were several opinions about the immediate prospects. General Norrie, of XXX Corps, has since said that to him “Alamein was the last ditch, and it was a real case of ‘Do or Die’, with every chance of stopping the enemy whose armour had been reduced to a mere shadow of its former self”.6 General Gott, on the other hand, seems to have thought more of the alternative. On the 30th he showed Brigadier H. K. Kippenberger, of the New Zealand division, a letter from Lieut-General Corbett,7 the Chief of Staff at G.H.Q., in which Corbett wrote that “the Chief” had decided to save the Eighth Army, and that the South Africans would retire through Alexandria and the rest through Cairo. Norrie wrote later that Major-General Pienaar of the 1st South African Division had been “openly saying that he thought it was wrong to stand at El Alamein, and that the best place was to go behind the Suez Canal”.8

The spirit in which General Auchinleck prepared to confront the enemy at El Alamein, however, was not downcast, even though he had with wisdom been planning a course to follow in the event of yet another failure. On the contrary, with his exceptional talent for perceiving his enemy’s difficulties, he judged that Rommel might over-reach himself (as the German High Command had also feared) and the opportunity be presented, not merely to halt him, but to throw him back. Auchinleck had on paper sufficient strength to take the initiative. He was resolved to seize it. Not all his battered formations were dispirited, least of all the New Zealanders, fresh from their break-out at Minqar Qaim. He had some battle-hardened but rested formations and some fresh troops from England.

Indeed, all was not well on the Axis side. The enterprising Germans, as they moved up to the El Alamein defences on the 30th, had only 1,700 first-line infantry and 55 tanks forward. Rommel was perilously short of supplies and largely dependent on what he had captured during the advance from Gazala. On the other hand he knew that his enemy was receiving men and weapons in large numbers and at last “there were already signs, in the new British tanks and anti-tank guns, of a coming qualitative superiority of British material. If this were achieved, it would clearly mean the end for us”.9

It seemed, therefore, that Rommel’s only chance of victory in the African war, was to press on as fast as he could drive his overtaxed troops. On the morning of the 30th he ordered the Africa Corps and the 90th Light Division to thrust forward before dawn next morning between the El Alamein position and Deir el Abyad. The 90th was then to wheel

northward and cut off the El Alamein Box while the Africa Corps swung south and took the XIII Corps in the rear. The Italian Trento Division was to attack El Alamein from the west and the Brescia to follow the Africa Corps. The XX Italian Corps with its one armoured and one motorised division was to deal with the Qattara Box. The Axis army was in new country. The advance would not only start in the dark but have to be made over unfamiliar ground.

Meanwhile in accordance with the tactical theories then in vogue on the British side, numbers of mobile columns had been formed. Two, each built round a battalion and two batteries of artillery, were formed in the South African division; only the 3rd South African Brigade was left in the box, whose eastern side was now undefended. The 50th Division was organised into three columns each possessing eight field guns. The 10th and 5th Indian Divisions also formed mobile columns

On the 30th the British northern rearguard passed through the El Alamein Box. The leading troops of the 90th Light followed and halted a few miles from the box where they were shelled and bombed. They made ready for the big attack ordered for the next day.

Events had moved so swiftly that Rommel’s Intelligence staff had an inaccurate picture of the British dispositions. They placed the X, not the XXX Corps, in the northern sector, and the 50th Division in the Alamein Box. They did not know that the 1st South African Division was forward. They placed an Indian brigade at Deir el Abyad instead of Deir el Shein and were unaware that two South African brigades were in the gap between Deir el Shein and Alamein. They placed the whole New Zealand division, instead of only one brigade, in the Qattara Box, and had the 1st Armoured Division west of that box whereas it was in process of moving into reserve about Ruweisat Ridge having only just arrived back from Mersa Matruh. In fact, coming back to El Alamein on the afternoon of the 30th, the 1st Armoured Division bumped against the Africa Corps in its assembly area for the attack Rommel was preparing to launch next day.

The British commanders expected the Germans to attack on the 30th1st and to thrust with their armour somewhere between the El Alamein Box and Bab el Qattara. If the attack fell on the northern gap, between the box and Deir el Shein, it was planned that the 1st Armoured Division (Major-General Lumsden10) would counter-attack from the north and the New Zealanders from the south. This plan was made at Eighth Army headquarters without appreciating that the 1st Armoured was dispersed as well as weary and in no shape to fight a battle next day.

The tired Axis forces attacked as planned on the 1st but made little headway. As a result of heavy going, a dust storm and powerful air attack the Africa Corps bogged down. The Corps then found, to its surprise, that Deir el Shein was occupied. Here was the fresh 18th Indian Brigade supported by nine Matilda tanks. The Germans became involved in eight hours of bitter fighting with the brigade which, unsupported by the British

armour, despite the optimistic prescriptions of army headquarters, was at length overrun and virtually destroyed; but the advance had been delayed and valuable time for counter-measures gained. Soon the Africa Corps had only 37 tanks running out of 55 that had opened the attack.

That afternoon the 90th Light Division came under the fire of all three artillery regiments of the South African division. The Germans halted and dug in but at 3.30 p.m., under persistent artillery fire from the South Africans’ guns to the north and east, the over-tried Germans began to panic and many men fled. At the end of the day the 90th Light’s diary recorded: “The situation has been clarified and a rout prevented, but the advance has broken down under concentrated enemy fire.” Next morning Rommel ordered the Africa Corps to abandon the southward advance and reinforce a renewed effort of the 90th Light to cut off the El Alamein position.

General Auchinleck was not unsettled by the disheartening loss of the 18th Indian Brigade. Although he had decided earlier that day that he was holding too wide a front and that the boxes at Naqb Abu Dweis and Bab el Qattara, garrisoned respectively by the 5th Indian and 2nd New Zealand Divisions, would have to be abandoned, on the night of the 1st he ordered preparation for a counter-attack from the south by the XIII Corps, employing the 1st Armoured Division and the New Zealand division.

Next morning the Axis infantry attack on the South African positions in the north was resumed at first light in dutiful compliance with the German commander’s exacting orders, but the 90th Light had lost heart and no real assault was made. The Italian X Corps (Trento Division and 7th Bersaglieri) to their north did no better. At midday, noting the continued northward concentration of the German forces, General Auchinleck confirmed the orders to the XIII Corps to attack the enemy’s flank and rear. In the afternoon the 1st Armoured set off on a preliminary move to the south-west but collided with the armour of the Africa Corps moving east, bent on its similar mission against the South African sector. The two armoured forces fought each other inconclusively until nightfall. In the south the Italian armoured forces, discouraged by air attack, had made no move.

Next day, 3rd July, marked the end of Rommel’s attempt to hustle the Eighth Army back from El Alamein before it could get settled. Rommel called for another effort from his flagging formations, though significantly they were told to probe for weaknesses first, and the over-spent 90th Light Division was permitted to dig in where it was. Once more the Africa Corps, which had only 26 tanks in running order (as against more than 100 in the 1st Armoured Division), was to thrust east to break in behind the South Africans, while the Italian XX Corps was to carry out the attack ordered the day before. Auchinleck’s plan was that the XXX Corps should hold its ground against the expected attack in the coast region while the XIII Corps threatened the enemy’s rear by executing the prescribed attack from behind Deir el Shein.

In the morning, probing for weak spots, the Africa Corps again bumped into the 1st Armoured Division, which then took up hull-down positions. The two armoured forces slogged it out astride the Ruweisat Ridge for the rest of the day. In the late afternoon, goaded by Rommel’s blunt and peremptory injunctions, the Africa Corps forced its way a short distance past the South African positions on their southern flank, but its will to fight on was spent.

Although the 1st Armoured Division could not disengage to carry out its intended left hook, the day was marked by a signal victory in the south which a New Zealand historian has described as “an outstanding episode in the Dominion’s military history”.11 Setting out in the morning for Alam Nayil, a typical cliff-walled outcrop emerging from the desert between the Ruweisat Ridge and the Qattara Box, the Ariete Division first brushed against the 4th Armoured Brigade and then came under fire from four New Zealand batteries.

This fire seemed so to disconcert the Italians that the 4th New Zealand Brigade (Brigadier J. R. Gray) attacked the Italian armoured division from the south. The leading battalion – the 19th – led by its carrier platoon advanced with fixed bayonets and captured some prisoners in an outlying group, and then made a systematic attack on a larger body of Italians of whom about 350 surrendered; 44 medium and field guns and many vehicles were captured there. Major-General Inglis, temporarily commanding the New Zealand division, at once ordered his 5th Brigade (Brigadier Kippenberger) to cut off the remainder of the Ariete at El Mreir. The brigade came under fire from the Brescia Division at El Mreir and eventually dug in.

That night Rommel realised that he had driven his staunch but dwindling forces to a standstill and decided to discontinue his attack on the makeshift British defence line for at least a fortnight. The fighting strength of each of his divisions, he reported on the 3rd, was no more than 1,200 to 1,300 men; the Africa Corps had only 36 serviceable tanks; he was short of ammunition.

On the morning of 4 July 1942 (wrote von Mellenthin of Rommel’s staff, after the war) the position of Panzerarmee Africa was perilous.12

Auchinleck, while aware that he had the upper hand, evinced less clairvoyance than usual and does not appear to have fully appreciated the enemy’s plight. Although on the night 4th–5th July he issued confident orders that the Eighth Army would “attack and destroy the enemy in his present position”, the confidence wore a little thin in the eyes of the New Zealanders next day when they received an order giving a new plan for withdrawal should the line collapse: the XXX Corps was to retreat by the coast to Alexandria, the XIII Corps (including the New Zealand division) inland to Cairo.

There followed a week of missed opportunities for the British, and thereafter more weeks of costly and mismanaged operations, yet for most

of that time Auchinleck was able to call the tune to both armies. The fault lay more in the execution of his plans than in their conception. Auchinleck had stepped down from the highest plane of command to undertake the day-to-day control of a formation that he had not first fashioned, tempered and hammered to perform its tasks in the way he desired. In the first place, its control and communications mechanisms were not geared or tuned to execute surely and swiftly the kind of flexible operations Auchinleck wanted; some parts of his command structure needed replacing, others redesigning. The kind of direct communication through report centres which Montgomery later instituted was needed to project a more accurate picture before the commander. In the second place the interpretations given to Auchinleck’s directions by the staffs of some subordinate headquarters, particularly Gott’s and Lumsden’s, resulted in orders that bore to the Commander-inChief’s conceptions but a shadowy resemblance, in which their original purpose was sometimes scarcely discernible.

On the 4th a series of confused and indecisive actions took place. Tanks of the 22nd Armoured Brigade probed along Ruweisat Ridge and overran part of the 115th Infantry Regiment (of the 15th Armoured Division). Some hundreds of Germans made as if to surrender, but their would-be captors were driven off by artillery fire. The Africa Corps’ war diary reported the 15th Division’s situation that day to be “most serious”. In retrospect it seems not unlikely that a resolute thrust from Ruweisat would have broken through.

That night Auchinleck gave the orders quoted above that the Eighth Army would “attack and destroy the enemy in his present position”. This was to be done by the XIII Corps which was to press round the enemy’s south-west flank and threaten his rear towards the coast road. But nothing much was achieved by the corps on the 5th, and for the Germans it was another precious day of reorganisation and of improvement of defences. On succeeding days, as the New Zealand historian has remarked:

Numerous plans were made by Army and Corps for action against the enemy’s rear and flank. Orders to execute them were never given.13

At 3 a.m. on 3rd July, the senior staff officer of X Corps, Brigadier Walsh,14 telephoned orders to the headquarters of the 9th Division near Alexandria that the division was to be formed into battle groups. One brigade group (less one battalion) was to be sent forward at once. Colonel Wells pointed out that the brigades lacked much essential equipment and that only one of the three field regiments was reasonably complete. Having been advised by General Blamey before his departure from the Middle East that the piecemeal employment of Australian detachments severed from the main formation should not be permitted, Morshead flew up to the Commander-in-Chief’s tactical headquarters, and sought an interview with Auchinleck. Before leaving, however, he gave directions that the 24th Brigade (less the 2/28th Battalion) should be prepared to move by 5 a.m.

next day provided that deficiencies in equipment and transport could be made good. After the war Morshead said that Auchinleck spoke to him very brusquely at the interview, and that the conversation went as follows:

Auchinleck: I want that brigade right away.

Morshead: You can’t have that brigade.

Auchinleck: Why?

Morshead: Because they are going to fight as a formation with the rest of the division.

Auchinleck: Not if I give you orders?

Morshead: Give me the orders and you’ll see.

Auchinleck: So you’re being like Blamey. You’re wearing his mantle.

Auchinleck, who was in no position to allow operational plans to be delayed by differences which could only be resolved satisfactorily to his wishes, if at all, by the slow process of inter-Governmental representations, agreed that the whole of the 9th Division should be brought forward as soon as practicable and employed under Morshead’s command. Morshead was ready to agree to the temporary detachment of a brigade group of the 9th Division to the XXX Corps on this basis. After seeing Auchinleck, Morshead met Norrie of XXX Corps, stayed at his headquarters for three hours, and then flew back in a Lysander aircraft to his headquarters on the Alexandria racecourse.15 Meanwhile Wells had been busily completing arrangements for the equipment of the 24th Brigade. Some of the needed equipment was brought forward during the day.

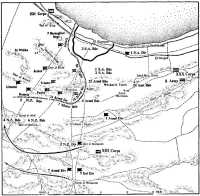

At midday the division came under the command of the XXX Corps and on the 4th the 24th Brigade Group (less the 2/28th Battalion) moved forward with many stops and starts on a road still crowded with vehicles moving eastward. By nightfall the 2/43rd was digging in on Tel el Sham-mama and the 2/32nd was halted nearby. The staff of XXX Corps informed Godfrey of the 24th Brigade that he was to keep his group mobile in readiness for a quick move. Meanwhile the 2/28th Battalion remained at Amiriya, and the 20th Brigade had taken over the defensive position in front of Alexandria vacated by the 24th.

The Australians, with their memories of Tobruk where the enemy had commanded the air, were gladdened by the constant evidence of Allied air superiority. Numerous fighter formations and light bomber formations (of Bostons and Baltimores) with wheeling fighter escort passed overhead each day; but German fighters were still to be reckoned with, and there were many dog-fights, with honours often divided.

The request for an Australian brigade had come down from Auchinleck because he believed that Rommel might be about to withdraw; Auchinleck had given orders to prepare for a pursuit. Morshead chose the 24th Brigade as the one to be sent forward because that brigade alone had completed its training in mobile operations. Exploitation to El Daba was an optimistic feature of the plans not only for this operation but also for

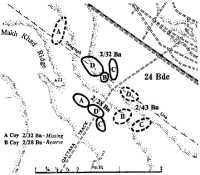

Situation, noon, 5th July

most other major operations in which the division was to be engaged in the coming month; but on no occasion did the exploitation take place.

On the 5th, Auchinleck decided that he was not able to thrust the XIII Corps towards the enemy’s rear and instead ordered both corps to converge on Deir el Shein. Rommel had meanwhile withdrawn the Africa Corps, XX Corps and 90th Division from front-line positions. The front was now held with the Italian infantry of the X and XXI Corps so that his striking force could be rested and reorganised in preparation for a resumption of the offensive later on.

On 5th July the 24th Australian Brigade moved to Ruweisat Ridge (the 2/32nd about Trig 96 and 2/43rd about Trig 93) with the task of establishing a firm base from which the 1st Armoured Division and various columns comprising “Wall Group” (under Brigadier R. P. Waller) might operate. In its new position the 24th Brigade, directly under the command of XXX Corps, relieved the headquarters of the 50th Division

and a force known as “Stancol” which moved back to the Delta for reorganisation. The composition of “Wall Group” – an assortment of units from various formations, brought together “pending reorganisation” – illustrates the degree to which the commanders were still thinking in terms of improvised columns. Waller was nominally the C.R.A. of the 10th Indian Division. One column – “Robcol” – comprised one battalion, one field regiment, detachments of anti-tank and anti-aircraft artillery and machine-gunners. “Squeakcol” possessed one battalion, a battery of field artillery and detachments of anti-tank and anti-aircraft artillery. “Ackcol” was under the command of Squeakcol and included the 3rd RHA, three companies of Coldstream and Scots Guards and supporting detachments. Morshead, on whom General Blamey had impressed his aversion to improvised organisation, toured the front and did not like what he saw.

Discussion began on the 6th of a plan for the 24th Australian Brigade to make a raid with two companies on a ridge west of Alam Baoshaza with the object of damaging anti-tank guns, demolishing derelict tanks and vehicles, obtaining information and killing or capturing any enemy troops encountered. This done the raiding force would return, or alternatively would remain and consolidate, supported at dawn by tanks and 6-pounders. The alternative plan was conceived as a preliminary step in the Eighth Army’s latest plan for a general attack to dislodge the enemy, in which the XXX Corps would have the task of taking Ruweisat Ridge. Morshead had gone forward to the XXX Corps on the morning of 5th July and had reconnoitred the area of the proposed operation with General Norrie and Brigadier Godfrey. On 6th July he again reconnoitred with Norrie and, objecting to the consolidation plan on the score that effective artillery protection could not be given,16 had a long conference with the Commander-in-Chief.

Brigadier Godfrey maintained that the support required for the alternative plan could not be made available and, after “so much time had been fruitlessly spent during the conference that reconnaissances by subordinate commanders . .. could not be carried out”, he sought and obtained a postponement of 24 hours.17

The New Zealanders, who had a contemporaneous part to play in the army’s larger plan – to thrust westward with their 4th Brigade – were not informed of the postponement. On the contrary, just as the brigade was setting forth, the division received an emergency operations message indicating a possibility that the enemy might be pulling out to withdraw westwards and telling the division to be ready to drive through deeply into the enemy’s rear. The 4th New Zealand Brigade carried out its original orders with élan, shooting up the Littorio Armoured Division in its leaguer before breakfast and playing merry hell. Before the end of the forenoon, however, the volatile mood at army headquarters was exhibited in new orders to the New Zealand division, this time to draw back from the Qattara Box to a position from which its guns could reach the Ruweisat

Ridge; this doubtless pleased Morshead. What caused the army commander’s renewed anxiety for the gap between his two corps at this moment is a matter for speculation, but he appears to have recast his thoughts as to how the next phase of the battle would be fought. The plan for a two-pronged thrust south of the Ruweisat Ridge had been abandoned.

By the 7th Auchinleck, having concluded that his plan to drive through the southern flank of the Axis army had failed, had decided that he would use the fresh 9th Australian Division to attack on the northern flank, where, he was convinced, only Italian troops would be encountered. The 26th Brigade Group (less one battalion) had been moved up on 5th and 6th July to positions giving depth to the defence on the coast sector. Divisional headquarters moved forward on the 7th to an area near El Imayid station and resumed command of the 24th and 26th Brigades, leaving a reserve group holding the Alexandria defences. Next day a “tentacle” from Army Air Support Control joined divisional headquarters; another “tentacle” was operating with the 24th Brigade. These tentacles not only reduced the delay in obtaining air support but enabled information about the enemy to be swiftly passed to divisions and brigades.

The “Reserve Group” at first included the 20th Brigade and all units and detachments not included in the two-battalion brigade groups sent forward, but the 20th Brigade Group (again less one battalion) was called forward a day later and by 8th July the “Reserve Group”, which was put under the command of Colonel H. Wrigley of the Reinforcements Depot, comprised the 2/13th, 2/28th, 2/32nd and 2/3rd Pioneer Battalions, some other units and detachments and the “left-out-of-battle” personnel from the units sent forward. In future each unit was to leave out of battle a certain number of officers and men of all ranks, who were to remain in the “B” Echelon area when the unit went into battle; thus if a unit had very heavy losses there would be a nucleus round which it could be re-formed. In an infantry battalion, for example, the second-in-command, 6 other officers and 61 others of specified ranks or qualifications were left behind; this was a minimum, as it was also laid down that an infantry battalion was not to go into action with its rifle sections of greater strength than one NCO and seven men. Within a week each of the infantry battalions left behind was called forward to rejoin its brigade, leaving its “L.O.B.” personnel at Alexandria.

When visiting the XXX Corps headquarters Morshead had learnt from Norrie himself that Norrie was returning to England and would be succeeded by Major-General Ramsden18 of the 50th Division. Morshead would not have been surprised therefore when Ramsden called at his headquarters at 6 p.m. on 7th July to tell Morshead of his new appointment. In his diary for that day Morshead wrote: “Ramsden has been commanding the remnants of his division (50 Div) remaining forward = 3 companies

plus various artillery groups.”19 This entry suggests an initial uneasiness on Morshead’s part, who would not have appreciated being subordinated to a colleague whose responsibilities immediately before had been less than Morshead’s. Nor was the situation made easier by the fact that Morshead, by virtue of his responsibility for the whole of the AIF in the Middle East, held the rank of Lieut-general, which had not yet been conferred on Ramsden. In the subsequent operations Ramsden did not win Morshead’s confidence and Ramsden found Morshead an intractable subordinate. Morshead said after the war that Ramsden twice complained to Auchinleck about his attitude.

On the 7th the role of the 24th Australian Brigade was amended to provide for a raid by one company with a detachment of engineers. The task was given to Captain Jeanes’ company of the 2/43rd (Lieut-Colonel W. J . Wain) with 4 officers and 64 others, plus 20 sappers and 6 stretcher bearers. By 10.30 p.m. on the 7th the raiders had formed up at Point 71, whence they moved off at 11 p.m. After 1,400 yards the leading platoon (Lieutenant Grant20) reported the presence of enemy troops about 800 yards to the north-west and promptly attacked; the other platoons fanned out to right and left and joined in.

Under fire from a variety of weapons Lance-Sergeant Curren’s21 platoon thrust forward for about 700 yards destroying guns and vehicles and taking prisoners. Grant’s platoon moved a similar distance and its sappers destroyed three disabled British tanks – one Honey and two Grants – and a gun. Lieutenant Combe’s22 platoon destroyed a gun and tractor. Private Franklin23 in Curren’s platoon, who acted with great dash throughout the attack, recaptured a British carrier, killing two Germans, and drove it back to his own lines. By 3 a.m. the company was back at Point 71. Throughout the raid the enemy fired wildly and sent up many flares. Soon flares, blasting guns and blazing tractors illuminated the area. When it was over one Australian was missing and seven had been wounded, four anti-tank guns, one field gun, three damaged British tanks and six tractors had been destroyed, and at least 15 enemy troops had been killed and 9 prisoners taken – all Germans of an anti-tank unit. The raid had an inspiriting effect on the division and on neighbouring troops.

On the enemy side the raid produced far stronger repercussions than the attackers realised. The commander of the 15th Armoured Division threw in the divisional reserve to counter what was regarded as a serious attack. Before dawn 19 tanks of the 21st Armoured Division – half the available total – were moved to the area where a threat of deep penetration had apparently arisen. Next day Rommel ordered that officers of forward units must stay awake all night to avoid being taken by surprise.

The fourteen days’ respite from offensive tasks tentatively vouchsafed – on 4th July – to the Axis Army’s few and stalwart but overtaxed German troops was soon curtailed. The prime motivator, it should seem, was Mussolini who had come across to Africa on 29th June to be there when Egypt fell to Axis arms, and perhaps to lay the foundations for a second Roman empire in a region where Caesars had once fought and loved, and who had announced on 6th July from his headquarters far from the fighting line that if there was no further attack for ten or fourteen days the chance of exploiting British unreadiness would be lost and the light forces available would prove insufficient to push through to Cairo and the Suez Canal. On the other hand taking the shorter coast route and capturing Alexandria, he thought, would bring splendid prestige. A top-level discussion ensued of the alternative merits of Cairo and Alexandria as targets for a resumed offensive, but Cavallero and Rommel decided that the best course was to cut the Red Sea supply route by striking through Cairo, thus avoiding the many obstacles to an advance through the Nile Delta. The Axis forces had somewhat recovered their tank strength, having some 50 German and 60 Italian tanks. The 21st Armoured and 90th Light Divisions and the Littorio Division were assembled opposite the centre of the XIII Corps, where they were joined by the 3rd and 33rd Reconnaissance Units brought up from the far south. They were told to advance to Alam Nayil and strike north on 9th July. To the north of them, astride the Ruweisat Ridge, were the 15th Armoured Division and the Trento Division of the Italian X Corps. Farther north, where the 9th Australian Division was soon to operate, the Italian XXI Corps held the line with the Trento and Sabratha Divisions.

As mentioned, Auchinleck had decided to abandon the Bab el Qattara Box, and on the night of the 7th–8th the New Zealand division had withdrawn. The Germans did not become aware of this until next afternoon. Their patrols in the evening confirmed that the box had been abandoned; but to Rommel this appeared too good to be true and, on the 9th, in dutiful compliance with the Field Marshal’s admonitions made in person at Africa Corps Headquarters, a full-scale attack on the “strong-point” was made by the two armoured divisions assembled for the offensive – one German and one Italian – using infantry, assault engineers, heavy artillery and tanks. The planned advance to Alam Nayil that morning was left to a detachment comprising part of the 5th Armoured Regiment, which was turned back by New Zealand artillery fire.

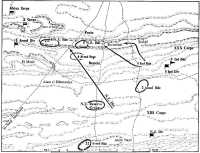

Having chosen to attack in the north, Auchinleck had ordered Ramsden to take the ridges of Tel el Eisa and Tel el Makh Khad, just south of the coast road. When these had been captured Auchinleck proposed that battle groups would advance south on Deir el Shein, and raiding parties attack the forward landing grounds about El Daba. The capture of Tel el Eisa was to be undertaken by the 9th Division; the 1st South African Division was to take Tel el Makh Khad. The 44th RTR with 32 Valentines was placed under Morshead’s command and the 1st South African Division was given 8 Matildas. The raiding force to make the foray towards

Daba comprised one squadron of tanks and one troop of armoured cars supported by a troop of field guns and another of anti-tank guns.

Where the black ribbon of the coast road issued from the Alamein Box, it traversed a flat, with a salt-marsh on the right, and continued on past a smooth-sloped white hill rising on the right to a height of almost 80 feet (Hill 26), which was the southern extremity of an elongated hill-feature stretching back across a saddle (Point 23) to a still higher feature, Trig 33. Below the steep southern side of Trig 33, the ground began to rise again gradually to rolling ground across the railway, shown on most maps as a ridge named “Tel el Eisa”. In a generally flat terrain the double-humped hill (Point 26 – Trig 33) lying between the sea and the road and railway was the dominating feature near the coast, providing as it did good observation not only southwards to the Miteiriya Ridge over the ground in front of the Alamein Box but also into much of the Eighth Army’s territory. On the other hand it shielded the coast tract against observation from farther west. The 9th Division’s task was to seize it and exploit south to the Tel el Eisa Ridge across the railway.

General Morshead conferred with General Ramsden and with General Pienaar of the South African division on the 8th, and on the 9th issued his orders for the attack, which was to open in the early morning of the 10th. The 26th Brigade was to capture and hold the features which have just been described. The brigade plan required the 2/48th Battalion to take the first objective, Point 26, and then to move on to the Point 23 saddle. Then the 2/24th Battalion, with the tanks, was to come up on the right over the sand dunes, swing left and take Trig 33. The 2/24th was then to exploit to East Point 24 south of the railway. The 9th Divisional Cavalry with one field battery under command was to be at 30 minutes’ notice to move forward from 8 a.m. on the 10th onwards.

Formidable support was to be given by artillery and aircraft. The division had the 7th Medium Regiment under command plus its own three field regiments, and such guns of the South African division as could bear were placed under the command of Brigadier Ramsay, Morshead’s artillery commander.24 There would be an air sweep over the area from 7.30 a.m. on the 10th plus bomber and fighter-bomber attacks.

Morshead’s tactical headquarters opened in the El Alamein fortress on the 9th and at dusk that day the attacking battalions moved to their assembly areas within the western perimeter of the fortress. Each battalion had under command a troop of anti-tank guns, a platoon of machine-gunners and some engineers, and, in support, a squadron of tanks.

The 2/48th Battalion, which was to open the operation by capturing Point 26, was commanded by Lieut-Colonel H. H. Hammer, who was to prove one of the most original and magnetic leaders of the AIF. When war broke out he was a major in a country light horse unit in Victoria. That was not a promising situation for one eager to obtain appointment to one of the first-formed divisions but Hammer “got away” in 1940 in

the Base Depot (A.G.B.D.). Thence just after the first Libyan campaign, to the pained surprise of the proud and veteran 16th Brigade, he was appointed its brigade major and served with it in Greece, and seven months thereafter. This colourful and buoyant commander, who had led the 2/48th since January 1942, gave his battalion a motto, “Hard as nails”, when he came to it, and the men gave it back to him, smarting under his strong hand until in action they found that his tight grip, his sureness and his quick decision protected them.

Hammer’s plan provided for an attack on Point 26 on a two-company front. To achieve surprise he decided that the first phase would be executed without artillery support and as silently as possible. There would then be artillery concentrations on Point 23, and the two other rifle companies would move through to the second objective. In the third phase the two companies on the left were to swing left to the Tel el Eisa station area and hold it.

On the move to the assembly area trucks carrying the 2/48th bogged in the salt-marshes beside the track and the consequent delay deprived the troops of the few hours of sleep the plan allowed for. The silent advance began at 3.40 a.m. A lone aeroplane was circling above.

Suddenly the night was lit up like day. The plane had dropped a parachute flare directly over the leading companies. The men froze, expecting the impact of a terrific outburst of fire. None came, and then the forward companies gathered momentum as they advanced, working their way along the ridge on either side of the crest.25

Before dawn broke, the Italians garrisoning Point 26 awoke to discover that they had been captured. Then a barrage of an intensity not heard before in the desert announced that the Eighth Army was making its first advance since the battle-tide had turned against it on the Tripolitanian frontier after CRUSADER. To veterans of the Great War, according to the Africa Corps’ war diary, it recalled the “drum-fire” of the Western Front. Artillery concentrations descended on Point 23 and, as daylight was breaking, smoke screens were put down on Trig 33. As soon as the guns ceased the two rear companies passed through and took Point 23 against only light opposition, capturing some prisoners including the commander of the 7th Bersaglieri Regiment. Some of the prisoners were caught in bed. So far-4,500 yards from the start-line – there had been no Australian casualties.

At 7.15 a.m. two companies swung south and, now under heavy shell fire, moved on Tel el Eisa station, 2,500 yards to the south-west. Captain Bryant’s company on the right and Captain Williams’26 on the left attacked with great dash. One platoon of Bryant’s company, for instance, charging with fixed bayonets, overran a battery of four guns, capturing 106 prisoners, mostly German. Here Corporal Hinson27 led his section with

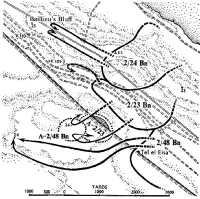

10th–12th July

bayonets fixed straight at two guns that were firing point-blank and whose crews did not surrender until the Australians were in the gun-pit. The companies reached the station, dug in and patrolled forward covered by the tank squadron until, about 9 a.m., six guns of the 2/3rd Anti-Tank Regiment arrived. About 40 dive bombers attacked Hammer’s headquarters on Point 26 ridge at 9.45, but everyone was well dug in and there was only one casualty. There were five more dive-bombing attacks that day by from 30 to 40 aircraft but little damage was done.

In the approach march the trucks carrying the 2/24th also got bogged in soft sand some miles from the forming-up ground, but largely as a result of the drive and energy of their commanding officer, Lieut-Colonel Spowers, whose tall familiar figure inspired confidence in everyone, the troops reached the start-line ahead of time. At 4.30 a.m. the 2/24th’s attack opened. There was little resistance until Point 26, already held by the 2/48th, had been passed on the left, but thereafter opposition increased. Throughout the advance Lieutenant McNamara’s28 platoon preceded the main body with the “commando role” of clearing the dunes of any enemy troops; the carrier platoon also ranged ahead. The carriers charged and overcame machine-gun posts and two anti-tank gun detachments whose Italian crews did not fire a shot.

At White Knoll a strong nest of machine-guns was encountered but was overcome by McNamara’s men and the carriers, reinforced by a

platoon from the reserve company. By 6.35 the men were digging in on Trig 33, whence Lieutenant Bell29 led his platoon forward and took four heavy guns and 100 Italian prisoners.

The plan provided that Captain Snell’s30 company, which had followed the main body from the start-line in trucks, should exploit to eastern Point 24, supported by two troops of tanks and by fire from a machine-gun platoon. Both tanks and machine-guns, however, were far to the rear, “hopelessly bogged” in the salt-marshes, so Spowers ordered the company to dig in on the reverse slope of Trig 33 and remain there. That afternoon at 5 o’clock 18 enemy tanks attacked across the salt-marsh to the west but most of them bogged and 14 were knocked out by anti-tank and artillery fire. Gunner McMahon31 towed his gun into action forward of Trig 33 and, even after three of his crew had been wounded and he himself hit in the leg and hand, continued to fire. He destroyed two tanks. Nine more tanks appeared on the southern slopes of Trig 33 and five of these were knocked out by the anti-tank gunners. The 2/24th Battalion lost 6 killed and 22 wounded in the day and took more than 800 unwounded prisoners and much equipment.

The 2/48th were also counter-attacked by tanks, though in smaller numbers; five, which appeared south of the railway line at 11 a.m., drove off the tanks that had been supporting the battalion. There the infantry had to endure very heavy shell fire, from which they sheltered in trenches that could be dug only a few inches deep because the ground was so rocky.

At 11.30 a.m. the 9th Divisional Cavalry (Lieut-Colonel H. E. Bastin) set out astride the main road to exploit to Sidi el Rahman and return to El Alamein station, but on high ground north of Tel el Eisa station the leading squadron came under artillery fire and found themselves threatened by the tanks that were engaging the 2/48th. Three hours later a bombing attack destroyed a carrier and caused seven casualties. The regiment was withdrawn during the afternoon.

At 2.30 p.m. ten tanks again attacked towards the 2/48th positions near the railway and ran over some of the shallow trenches in which the men lay. When they had passed some of the men hurled sticky grenades at them. Sergeant Haynes32 jumped out of his trench and planted a sticky grenade in a tank and then fell wounded. Fire from the field and anti-tank guns prevented the tanks from crossing the railway line and forced them back.

Thrice more the enemy tanks attacked, getting in amongst the slit trenches of both Bryant’s and Williams’ companies, but both companies, encouraged by the unflinching example of their commanders, held all their positions. On the last occasion the tanks reached the defenders’ positions near the station, but withdrew after the anti-tank guns had

knocked out six of the ten. When one crew leaped out and sought to escape Sergeant Longhurst33 of the 2/2nd Machine Gun Battalion tried to fire on them, but they were behind a slight rise. Longhurst then lifted the entire gun and tripod and, with the help of another man, brought fire to bear on the enemy, who promptly surrendered.34

Just before dusk, after two hours of shelling, the enemy mounted a further attack on the forward companies with both tanks and infantry. The tanks overran the forward posts of Williams’ company on the right. Hammer had anticipated such an attack and had arranged for a counterattack to be launched by a force, commanded by Major Tucker, of one company (Captain Shillaker’s35) plus two platoons. Williams’ company was in a critical position when the counter-attack went in at 8.30 p.m., but as soon as Captain Shillaker’s company arrived it charged, firing from the hip, and forced the enemy back across the railway. In this counter-attack Sergeant Derrick,36 who in the initial attack had led an assault on three machine-gun posts and captured many prisoners, attacked two tanks with sticky bombs and damaged them. When the fight was over Shillaker’s company had lost only one man killed and one wounded but 13 were missing from Williams’ company. By the next morning the 2/48th had suffered 39 casualties, but they had taken 89 German prisoners and 835 Italians and captured 27 guns of 35-mm to 75-mm calibre. In all the brigade knocked out 18 tanks and took 1,150 prisoners.

Farther south, on the 9th Division’s left, the South Africans reached Tel el Makh Khad, cleared it of enemy and then withdrew to the Alamein Box.

The German command reacted sharply to the attack of XXX Corps. At the main headquarters of Rommel’s army on the coast only a few miles to the west the “alarming news” was received that the Sabratha Division (whose infantry comprised only two regiments each of two battalions) had been put to flight. Lieut-Colonel von Mellenthin in charge at Rommel’s headquarters was “startled to see hundreds of Italians rushing past the Headquarters in the final stages of panic and rout. ... It was clear to me ... that Sabratha was finished37 – their artillery was already ‘in the bag’ – and something must be done immediately to close the road to the west.”38 He collected “headquarters troops” which included machine-guns, anti-aircraft guns, and some infantry reinforcements who happened to arrive, to plug the gap, which he later strengthened with the main body of the 382nd Regiment of the 164th Division, which was in course of arriving by air.

Rommel himself, who was in the south at Qaret el Abd to superintend the launching that day of his renewed offensive to reach Cairo and had heard the drumming of guns in the north with foreboding, also acted quickly. “To restore the situation the Commander-in-Chief brought up a quickly-formed battle group of 15th Armoured Division and his headquarters’ battle group (Kiehl Group). This force was to attack

the enemy’s southern flank and cut him off from Alamein stronghold. The battle groups advanced to the attack about midday but made very slow progress owing to terrific shell-fire from Alamein stronghold.”39 Meanwhile the Africa Corps was told to make only a limited advance in the south. The two battle groups employed in the north had 15 or 16 German tanks.

Early on the 11th “Daycol”, a raiding force built round a squadron of the 6th Royal Tanks, manning Stuarts, was sent out from the Alamein fortress towards Miteiriya Ridge to threaten the enemy’s line of communications. The column included a troop of 6-pounders, a troop of 25-pounders and a troop of armoured cars, all British; the 57th Australian Field Battery, a platoon of the 2/2nd Machine Gun Battalion and a platoon plus four carriers of the 2/23rd Battalion. It left its start-line at 5.30 a.m. Half an hour later, just short of its objective, it came under fire from about two companies of infantry. These were swiftly overrun and 400 Italians surrendered. But in the early afternoon a heavy artillery duel developed and at 1.30 Daycol withdrew, having destroyed eight Italian field guns and other weapons and taken 1,024 prisoners.

At 4.30 a.m. that day the 2/24th set out to capture East Point 24 which it had been unable to secure in the attack made the day before. It had formidable support: the fire of three Australian field regiments and one South African, and of the 7th Medium Regiment, and the support of a squadron of the 44th Royal Tank Regiment with 8 Valentine tanks, which were to assist in the later stages. Captain Snell’s company made the attack, reached the objective without a single casualty and took 500 prisoners. The tanks covered the company while it dug in. Thereafter the company was lashed with intense artillery and mortar fire and by the end of the day 25 men had been killed or wounded. At 6 p.m. Spowers decided to reinforce Snell. He appointed Major Budge to command all troops on Point 24 and at dusk sent Captain Monotti’s40 company forward. That day one company of the 2/23rd moved up to join the 2/24th and one joined the 2/48th.

All day the 2/48th had been under heavy shell fire but had toiled on, improving weapon-pits and laying mines Every concentration of enemy troops had been dispersed by heavy and accurate artillery fire.

A danger faced by those moving about in the thinly-held battle area was starkly illustrated by a misadventure to a group of officers who were returning from a conference at the 26th Brigade’s headquarters in the small hours of the 12th. This included Colonel Spowers who was returning to his battalion, Major Wheatley41 of the 2/2nd Machine Gun Battalion, Lieutenant Mulgrue of the 2/3rd Anti-Tank Regiment and a driver, all in a jeep. They did not arrive at their destination and next day examination of the jeep’s tracks showed that the driver, who had been following a track at the edge of the sand dunes fronting the sea-shore, instead of turning off to the left just east of battalion headquarters, had continued

on into enemy territory. Later it was learnt that all had become prisoners. Three nights later Captain Tivey42 of the 2/23rd Battalion drove into enemy territory at the same point and was captured.

The battle report of the Armoured Army of Africa gives the German version of the XXX Corps’ operations on the 11th including those of the 2/24th Battalion against Point 24:–

Early next morning the enemy again attacked after a very heavy preliminary bombardment. In this attack two Bersaglieri strongpoints, which had held firm the previous day, fell very soon. A battalion of Trieste which was committed to plug a gap was overrun and wiped out. This made the situation so serious that almost the whole of the army artillery had to be committed in the northern sector. Before evening all the other battalions of the Trieste Division were brought forward to the Point 21 area to seal off the advance. Reconnaissance Detachment 3 was moved into the area south-west of Point 2343 to prevent the enemy from breaking through to the west. “I was compelled to order every last German soldier out of his tent or rest camp up to the front,” Rommel wrote later, “for, in face of the virtual default of a large proportion of our Italian fighting power, the situation was beginning to take on crisis proportions.”44

On 11th July Rommel decided to smash the British penetration with a strong counter-stroke using the 21st Armoured Division. He brought the division up from the south on the 12th and decided to capture the Alamein Box next day and cut off the Australians on Tel el Eisa. “The attack was to be supported by every gun and every aeroplane we could muster.”45

In the meantime Auchinleck, noting that Rommel was transferring armour to the north, set in train preparations for an attack from the south and centre in the Ruweisat Ridge region similar to the operation which had been in contemplation when the 24th Brigade’s raid in that sector was being planned. The staff of Eighth Army, however, did not know that although one of the enemy’s armoured divisions and about 30 German tanks (approximately two-thirds of the total German tank strength) were in the north, the bulk of his armoured forces were still in the south under the firm command of the Africa Corps (Lieut-General Nehring) and poised to undertake the projected offensive as soon as the detachments in the north returned.

On the 12th the 9th Division enjoyed freedom from ground attack until the late afternoon but suffered artillery bombardment of mounting intensity as the afternoon wore on, particularly on the ridges of Hill 33. About 6 p.m. German infantry attacked in waves along the whole of the front of the 2/24th Battalion, of which Major Budge had assumed command, but were met by sustained artillery fire from the 2/8th Field Regiment and British howitzers. Captain Anderson’s company of the 2/23rd Battalion, with which the 2/24th had been reinforced, bore the brunt of the attack, fighting from exposed ground forward of Trig 33.

Private Buckingham,46 maintaining fire though with little cover, had first one and then another Bren gun shot out of his hands. Corporal Knight47 of the 2/2nd Machine Gun Battalion played a gallant part which inspired the men fighting from their shallow pits around him. Knight and his men carried their guns forward under fire to an exposed position on top of the hill. There they blazed away at the enemy, Knight often standing nonchalantly in front of his gun positions to pick out targets. He moved his guns seven times; nor were they ever pin-pointed by the enemy. But there were many casualties in the company and Anderson was mortally wounded when his trench was hit.

By 9 p.m. the attack – by Germans of the 104th Lorried Infantry Regiment – had died down. It was estimated that they left 600 dead and that the machine-gun platoon had accounted for most of them. Captain Harding48 took over command from Anderson and for the next five days led this battered company in most resolute defence of its vital ground.

On the morning of the 13th the 26th Brigade was warned to expect a strong attack by the 21st Armoured Division. Rommel’s plan for the day, however, was not to overrun the Australians but to cut them off by enveloping their rear, and although East Point 24 withstood two assaults with the aid of the concentrated artillery fire of five regiments, the main onslaught was made on the South African division south of the Alamein Box. As before, the South Africans held their ground.

On this day of anxiety the 9th Division received an order to move south to a position south-east of Jebel Bein Gabir, leaving the 26th Brigade under the South African division, but next day, after preliminary reconnaissances and moves, the order was countermanded: only the 20th Brigade was to go. The reason for these orders was not known then at divisional headquarters, but they resulted from Auchinleck’s preparations for a renewed thrust in the centre of the front along the Ruweisat Ridge. Auchinleck’s headquarters, the location of which was kept secret and never shown on any map, was to the rear of the chosen area for attack, and thus vulnerable should an enemy counter-thrust succeed in piercing the British front. The locality to which the 20th Brigade was to move was one of the mined defensive areas known as “boxes” and was just to the rear of Auchinleck’s headquarters.

Rommel ordered the 21st Armoured Division to attack the Australians again on the 14th. The night of the 13th–14th brought signs that an onslaught was coming the forward troops reported infantry and guns moving into position and the artillery fired on many targets. In midmorning of the 14th enemy infantry edged closer to the cutting area and to the southern slopes of Trig 33 and three German tanks came up near Captain Mollard’s49 company of the 2/24th to cover a party of engineers

who set about lifting the minefield. The infantry weapons could not counter the standover tactics of the tanks and no anti-tank guns were able to bring effective fire to bear on the German tanks in the positions where they had halted. Defensive artillery fire was called down, which was probably effective since the attack was not further pressed for some time. In mid-afternoon, however, and again as night fell, German infantry and tanks, using close infiltration tactics, attacked the two companies on East Point 24, the tanks crumbling the weapon-pits when they could. One incident must suffice to illustrate the spirit in which the defence was conducted. When two Bren-gunners were crushed in their pit, Private Dwyer50 leapt up and, while the fire-fight was at its height, dug them out in plain view of the enemy. The first attack was repelled by keeping the upper hand in the fire-fight – the tanks were kept closed up, one commander who poked his head up to have a look being promptly shot dead – and the defenders hung on against the second attack until night blinded the tanks and action ceased. Budge, realising that in their isolation and with flanks exposed the two depleted companies could not withstand sustained attack, ordered their withdrawal at 9.30 p.m., and having no transport they came out on foot. The anti-tank gunners took the breech-blocks from their guns; later they returned with towing vehicles and brought the guns out.

Some of the German tanks engaged in the attack on Point 24 afterwards moved across the front of the forward companies of the 2/48th about Tel el Eisa station. Failing to draw fire, eight of the tanks crossed the railway line and advanced on Point 26. They were then engaged by field guns, swung west to avoid this fire and came within close range of two Australian anti-tank guns. A brisk fire-fight developed in which all neighbouring infantry joined. Some tanks burst into flames and the rest soon withdrew. The 2/3rd Anti-Tank Regiment reported having destroyed seven of them in quick succession; four of these were hit by Sergeant Digby’s51 gun and three by Bombardier Muffett’s.52 Tanks of the 1st Army Tank Brigade were hurried forward ready to give support next morning. Dawn revealed ten burnt-out German tanks left on the battlefield.

Rommel had intended to renew the attack on Tel el Eisa in some strength on the 15th but the attack launched by Auchinleck on Ruweisat Ridge forced him to reduce the scale of the assault. Auchinleck’s general intention, as stated in his orders, was to break through the enemy’s centre and destroy the enemy forces deployed north of Ruweisat Ridge and east of the El Alamein-Abu Dweis track. The XXX Corps was to take the eastern part of the ridge, then attack southward from Tel el Eisa and take the Miteiriya Ridge. The XIII Corps was to advance by night to Trig 63 at the western end of the ridge and then exploit to the northwest. On the 14th it was decided to make the attacks that night; the two corps were ordered to reach their objectives by 4.30 a.m. on the 15th.

The orders of the XIII Corps and 1st Armoured Division giving effect to this clear if over-simplified directive had enunciated more limited objectives and purposes, however, and had discarded as though it had been useless or pious embroidery, the statement of the broad intention which should have given impulse and cohesion to the forces operating. Conferences had been held but had not produced a common understanding of how the formations were to work together. The New Zealanders thought that they had a promise of close and firm armoured support when they got on their objective, whereas General Lumsden’s understanding seems to have been that the armour need not come up unless nor until there was a call for its assistance. The two armoured brigades were not told to get up on the New Zealand division’s flanks but only to be prepared to move. As the New Zealand historian has commented:–

Moreover, the instruction to both brigades that they “will be prepared to move” implied a waiting role and allowed the brigade commanders a discretion which, with fateful consequences, they exercised in the operation.53

In the XXX Corps sector the assault was made by the 5th Indian Brigade. The leading battalion was held up east of Trig 63 and the second, which had come under very heavy fire, had to retire.

The 2nd New Zealand Division made the attack in the XIII Corps sector with its 5th Brigade on the right and 4th on the left. Setting out at 11 p.m. it reached minefields a little after midnight and soon the men were under machine-gun fire and illuminated by enemy flares. They pressed on leaving many posts – more than they knew – to be mopped up later. Shortly before dawn the 5th Brigade was on its objective but with its left battalion in some confusion; the 4th Brigade had reached its objective on the left but was also somewhat scattered. At dawn the New Zealanders were awaiting the arrival of the tanks of the 22nd Armoured Brigade, but both this brigade and the 2nd which was to support the Indians were well to the rear awaiting orders.

Among the enemy troops inadvertently bypassed by the New Zealanders were about eight tanks of the 8th Armoured Regiment. In the half-light of dawn, these came in on the 22nd New Zealand Battalion, which at first mistook them for the expected British tanks, and attacked. Eventually, after a fierce fight between German tanks and New Zealand anti-tank gunners, about 350 New Zealanders were taken prisoner.

In the morning, General Nehring commanding the Africa Corps and in charge on the southern front reported the attack at Deir el Shein to Rommel, who ordered German units to converge on the area of penetration: the 3rd Reconnaissance Unit and a battle group of 100 infantry (with supporting arms) of the 21st Armoured Division from the north and the Baade Group (a battle group of 200 riflemen with supporting artillery) and 33rd Reconnaissance Unit from the south. At 5 p.m., the group from the north and the 33rd Reconnaissance Unit, together with tanks at hand of the 15th Armoured Division, opened a counter-attack.

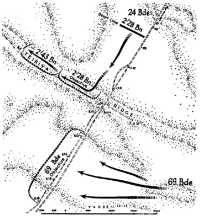

The attack on Ruweisat Ridge, 14th–15th July

The Baade Group failed to get to the battle. The New Zealanders were too thin on the ground to cope with the onslaught and the British tanks behind them were still awaiting orders. The New Zealand 4th Brigade was overrun. At 6.35 p.m. some tanks of the 2nd Armoured Brigade went

forward to the edge of the battle and gave some support. At 10 p.m. General Gott of XIII Corps authorised Inglis to withdraw to a line from Trig 63 to a position south-west of Alam el Dihmaniya The New Zealand division’s exposure to the German armour and the failure of British armoured brigades (whose tank strength so greatly exceeded that of the Germans) to be there alongside to give battle left an aftermath of bitterness and distrust of the armour and also of the commanders responsible.

Up to a point the British attack had been a brilliant success. Some 2,000 men of the Brescia and Pavia had surrendered, and in Rommel’s words the “line south-east of Deir el Shein collapsed”; but the success was not exploited and Nehring’s prompt counter-attack turned it into a costly reverse. The 2nd New Zealand Division lost 1,405 killed, wounded or missing.

The fundamental fault was the failure to co-ordinate infantry and armour (wrote Brigadier Kippenberger later). ... The attitude of the armour commanders at that period was not helpful, but I do not think we of the infantry did nearly as much as we could or should have done to ensure that we fought the battle together.54

Meanwhile the 20th Brigade Group (Brigadier Windeyer) had moved on the afternoon of the 15th to the defensive positions close to General Auchinleck’s tactical headquarters. Late that night a liaison officer from Eighth Army was sent to Windeyer’s headquarters with orders that the brigade was to move at 5.30 a.m. next morning in three battalion groups, each in mobile box formation, to a position (Mubarik Tomb) behind the 5th Indian Division, against which an enemy counter-attack was expected. There the brigade formed next morning a hastily improvised and dangerously exposed defence line. These orders were given without Morshead’s knowledge. When Morshead learnt what had occurred, he telephoned General Auchinleck and said that he was dumbfounded that Auchinleck should have done this; it was opposed to their agreement, he said, and opposed to Morshead’s charter. Auchinleck agreed to return the brigade, but soon afterwards sent news that he was being attacked heavily, whereupon Morshead agreed that the return of the brigade should be deferred, but asked to have it back as soon as possible. The brigade was released and returned to the 9th Division on the 17th.

On the 15th the 26th Australian Brigade had been fairly heavily engaged when Rommel resumed the attack with the forces left to him after sending reinforcements to Nehring. During the night of the 14th–15th patrols of the 2/48th could hear German voices and the engines of vehicles on their front near Tel el Eisa railway station. These were fired on, and in the morning it was discovered that 15 German vehicles were close to the wire and two machine-guns and two anti-tank guns had been established at or near the railway station. There was a sharp fight in which 32 Germans were captured and others killed. The vehicles were captured but later destroyed after the ammunition and equipment they contained had been salvaged. That night a patrol from the neighbouring company of the 2/48th had attacked a German party lifting the minefield, taking seven prisoners.

Meanwhile in front of the 2/24th Battalion dawn on the 15th had revealed 10 enemy tanks and infantry in 70 troop carriers approaching Trig 33. At 7.30 a.m. after an intense artillery barrage an attack was made by some 35 tanks and about seven companies of infantry. The tanks came up to the foot of Trig 33 and fourteen tanks reached that feature but the following infantry were driven back by the 2/24th and later the tanks withdrew to dead ground. At 8.15 a.m. there was a second attack from the north with 25 tanks and this too was beaten off with the help of a counter-attack by light tanks of the 44th Tank Regiment. A third attack without tanks was repulsed after about half an hour’s fighting. A fourth attack by both tanks and infantry at midday was broken up by artillery and machine-gun fire. Ten German tanks were destroyed in the day and the Australians took 63 prisoners.

At 4.15 a.m. on the 15th the 5th Armoured Regiment was ordered to continue the attack against the Australians with such sub-units as were available. The II/104th Battalion advanced across the railway north-west of the cutting at 5.50 and at 8 o’clock 12 tanks of the 5th began thrusting from the west north of the railway

and by 2 p.m. reported that it had reoccupied the “former positions” but was being prevented by artillery fire from moving up heavy weapons.55

Later that afternoon this advance had to be broken off and the 5th Armoured Regiment moved south-east to meet the attack “south-east of the El Alamein Box” leaving one battalion of the 104th Regiment to hold on in the northern sector. The 5th was ordered to attack in the south-east at 4.30 on the 16th.

That night plans were made to recapture the double Point 24 feature next morning (the 16th) with two companies of the 2/23rd and five tanks. The attack succeeded brilliantly at first. Captain Cromie’s56 company with two troops of the 8th RTR set out at 5.20 a.m. At the railway cutting an enemy post brought two forward sections under heavy fire at close range. Lance-Corporal Bell57 promptly led his section to a firing position on the flank and himself moved out under fire and attacked the post with grenades and sub-machine-gun. Bell and his men swiftly silenced the post, which was manned by 30 Germans. By 6.30 a.m. Cromie’s company had taken East Point 24.

Captain Neuendorf’s58 company passed through Cromie’s with three troops of the 44th RTR and advanced under continuous shell, mortar and small-arms fire. Neuendorf, wounded in the hand, advanced calmly in front of his men exhorting them and controlling movement, keeping his company never more than 50 yards behind the leading tanks; when he ordered his men to lie he would remain standing. By 7.45 a.m. West Point 24 had been taken. On the objective, Neuendorf went through a belt of fire to give first aid to a wounded man and, while returning, was killed by a shell. The attackers had taken 601 prisoners of whom 41 were Germans, including three colonels, one a German.

The two companies were at once subjected to intense and accurate artillery, mortar and machine-gun fire and soon 90 of the 200 men engaged had been killed or wounded. The prisoners were all sent back and, at

11.30, Lieut-Colonel Evans, after moving about the whole area to see for himself, ordered a withdrawal because the area was commanded by the enemy and he could perceive no tactical value59 in it, he had no artillery support or Vickers guns, no anti-tank guns had arrived and casualties were mounting. The withdrawal “was carried out in a most soldierly and able manner without further casualties”.