Chapter 14: Launching the Battle

In September and October the Eighth Army rapidly gained strength. In the first nine months of 1942 2,453 tanks and 2,709 guns had reached the Middle East. In the first eight months there had arrived from the United Kingdom 149,800 men for the land forces, including two divisions of infantry and one of armour, 32,400 men for the RAF and 9,800 for the navy. In addition some reinforcements had been received from India and the Dominions. From India 32,400 men had come, mainly as reinforcements, and there had been smaller numbers of reinforcements from Australia, South Africa and New Zealand.

Between 1st August and 23rd October 41,000 reinforcements joined the Eighth Army and, Alexander recorded, over 1,000 tanks, 360 carriers and 8,700 vehicles were sent forward. In September and early October the army’s artillery was strengthened not only by the divisional artillery of the newly-arrived 8th Armoured and 44th and 51st Infantry Divisions but by two medium and six field regiments. By the third week of October the guns in the Eighth Army included 832 25-pounders, 32 4.5-inch guns, 20 5.5-inch, 24 105-mm; also 735 6-pounder and 521 2-pounder anti-tank guns.

The Eighth Army commanded a powerful superiority of tanks. By 23rd October 1,029 were ready for battle and there were some 200 replacements standing by and about 1,000 in the workshops. The German armoured divisions, on the other hand, had only 218 serviceable tanks (and 21 under repair) and the Italian divisions 278 when the battle opened.1

In the first half of September 318 Sherman tanks arrived at Suez and with these General Alexander intended to equip three of his six armoured brigades.2 For the first time the Eighth Army had been given tanks which could match the enemy’s in range and manoeuvre and outshoot all his tanks except the formidable Mark IV Specials, of which he had no more than 30.

The successful pursuit of the defeated Axis army would require far more vehicles than had been available hitherto. They were now available. By 23rd August the Eighth Army had the equivalent of 46 general transport companies and six tank-transporter companies; seven more general transport companies were in reserve.

More than 500 aircraft were available to Air Vice-Marshal Coningham to support the army whereas the Axis air forces could deploy only about 350 based in North Africa, though support could be given from Crete and quick reinforcement from Italy was possible; nor did Coningham have any fighters to match the German Messerschmitts F and G. By late

October the Desert Air Force was organised into No. 211 Group (with 17 fighter squadrons), No. 212 Group (8 fighter squadrons), No. 3 S.A.A.F. Wing (3 day-bomber squadrons), No. 232 Wing (2 day-bomber squadrons), No. 12 American Medium Bombardment Group (3 squadrons), No. 285 Wing (3 reconnaissance squadrons and 2 flights). Other squadrons, including some equipped with night-bombers, and long-range fighters, were available to give direct support to the army.

While supplies in such abundance were reaching the desert army after the battle of Alam el Halfa, Montgomery’s confidence in the outcome of the attack which he was planning for their employment was growing, but Churchill was becoming impatient to see them used earlier than Montgomery or Alexander planned. In the background was the ever-deepening peril of Malta, whose scanty supplies, supplemented meagrely in August at appalling cost, were likely to be exhausted by October. However General Brooke deterred the British Prime Minister from pressing Alexander to attack before he was ready and the messages from London inquiring as to the intended date of the offensive were in surprisingly mild terms.

The original intention of the Middle East Command to open the British offensive in September had to be revised after the Battle of Alam el Halfa. Alexander and Montgomery had decided that it would be necessary to attack by night in order to penetrate the enemy’s formidable defences and that to clear the minefields and deploy the armour a night of bright moonlight would be required. When the Alam el Halfa fighting had died down the September full moon was only three weeks away. That was quite insufficient time to allow for the training, extensive preparations and detailed planning required for the kind of stage-managed, large-scale army attack that Montgomery intended to launch. Alexander and Montgomery were determined that the army and especially the armoured corps should have sufficient time for training Full moon was on 24th October and, with Montgomery’s agreement, Alexander chose the 23rd as the opening date of the offensive.

Montgomery had a hand in preparing Alexander’s message to the British Prime Minister notifying this decision.

I remember Alexander discussing the Prime Minister’s signal with my chief (wrote de Guingand later). Montgomery took a sheet of paper and wrote out very carefully four points on which to base a reply. These were:

(a) Rommel’s attack had caused some delay in our preparations.

(b) Moon conditions restricted “D” Day to certain periods in September and October.

(c) If the September date were accepted the troops would be insufficiently equipped and trained.

(d) If the September date were taken, failure would probably result, but if the attack took place in October then complete victory was assured.3

Another consideration that affected the timing was that the Allied invasion of French North Africa was to begin on 8th November. It was desirable that there should be a decisive victory over the Axis forces at El Alamein just before the invasion so as to impress the people of French

North Africa and the Spanish dictator, General Franco. The date chosen by Alexander and Montgomery for their offensive preceded the projected date of the invasion by just under a fortnight.

I was convinced (wrote Alexander later) that this was the best interval that could be looked for in the circumstances. It would be long enough to destroy the greater part of the Axis army facing us, but on the other hand it would be too short for the enemy to start reinforcing Africa on any significant scale. Both these facts would be likely to have a strong effect on the French attitude. The decisive factor was that I was certain that to attack before I was ready would be to risk failure if not to court disaster.4

The Middle East Commanders-in-Chief planned two operations for the purpose of aggravating Rommel’s supply difficulties while the Eighth Army was getting ready to attack. Raids were to be made on Benghazi and Tobruk with the object of destroying or damaging port equipment and fuel storages. On 13th September attempts to raid installations were made at Tobruk by both overland and sea-borne parties and at Benghazi by a column from Kufra. Both raids failed.

Nobody understood better than Montgomery that to possess abundant supplies was not enough. The requirement was to employ them with effect. The Eighth Army’s plan would be more than a statement of tasks to be accomplished on the first and succeeding days of an attack. Those would be only the culminating moves in a series of closely correlated operations taking place for weeks before. The plan would embrace a thousand and one things, and more, that had to be done before the first shot would be fired. First an administrative network and supply system had to be designed, set-up, concealed from the enemy, and so placed as to best serve the forces where they would fight. Then special training had to be devised and carried out to prepare all arms and services- for the exact tasks they would be expected to perform. And while the army was making ready the enemy was to be made unready by every conceivable ruse.

The design of the administrative lay-out and the location of supply points and forward dumps had to be subservient to a tactical plan, which had to be settled first. The tactical plan in turn had to fit the ground and meet the situation presented by the enemy’s defensive measures.

From the time when the front stabilised itself after Auchinleck’s attacks had failed to turn Rommel’s advance into a retreat, the Axis forces had been preparing a strong defence line from the sea in the north to the Taqa plateau in the south. The operational task that confronted General Montgomery and his army was incomparably more difficult than anything previously essayed in the Middle East, for Rommel was turning to his own advantage the closed-flank defensive potentialities of El Alamein which had caused the British four months before to stand there against his drive to the Nile delta and the Egyptian capital. And the German commander whose tactical skill had so far been mainly demonstrated in swift manoeuvring of armoured mobile forces showed now (as he did later in organising the defence of the French coast) that, if the occasion demanded,

he would fully exploit the possibilities of static defence to entangle an advancing enemy. Realising after Alam el Halfa that air-power could tip the scales if he tried conclusions with the British armour in a war of movement, he adopted an entrapping, spider-web scheme of defence.

We saw to it (he wrote) that the troops were given such firm positions, and that the front was held in such density that a threatened sector could hold out against even the heaviest British attack long enough to enable the mobile reserve to come up, however long it was delayed by the RAF

Coming down to more detail, the defences were so laid out that the minefields adjoining no-man’s land were held by light outposts only, with the main defence line, which was two to three thousand yards in depth, located one to two thousand yards west of the first mine-belt. The panzer divisions were positioned behind the main defence line so that their guns could fire into the area in front of the line and increase the defensive fire-power of their sector. In the event of the attack developing a centre of gravity at any point, the panzer and motorised divisions situated to the north and south were to close up on the threatened sector.

A very large number of mines was used in the construction of our line, something of the order of 500,000, counting in the captured British minefields. In placing the minefields, particular care was taken to ensure that the static formations could defend themselves to the side and rear as well as to the front. Vast numbers of captured British bombs and shells were built into the defence, arranged in some cases for electrical detonation. Italian troops were interspersed with their German comrades so that an Italian battalion always had a German as its neighbour.5

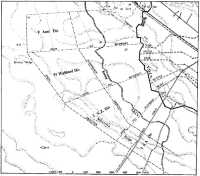

The defences, nowhere weak, were much more strongly developed in the northern part with which the 9th Division was to be concerned than in the south. The main defended zone in the north was some 6,000 yards wide and traversed laterally by two main lines of defence protected by minefields between which secondary minefield belts were laid in a random rectangular maze. Between these secondary fields were diagonal lanes of unmined ground so located that tanks advancing along them would expose their vulnerable sides to anti-tank guns. Behind the main defensive belt was an anti-tank gun line comprising both guns and dug-in tanks. These guns were carefully concealed, and firing, as they did, with flashless charges, were practically impossible to spot even when in action. Rommel laid great store on the ability of his “devils’ gardens” to block a British advance but Kesselring has recorded that he had less faith in their efficacy.6 No tank force could penetrate that triple defence barrier. The long-range concealed anti-tank gun was in fact beginning to relegate tank forces to the cavalry role that a temporary invulnerability had enabled them for a time to surpass.

Montgomery made two plans for the battle. The first was given out on 15th September, the second on 6th October; but the second was built onto the framework of the first so that none of the planning, preparation and training so far done was wasted.

Both plans recognised that a condition imposed by the enemy’s preparations was that the initial onslaught would have to be made by a strong infantry assault force. In Montgomery’s original plan the further development of the operation rested on the major premise, not inappropriate to

conditions in which tanks were becoming highly vulnerable, that to force the enemy to attack the British armour on ground of its own choosing (though it might be a lucky attacking force that found itself free to choose its own ground) offered better prospects of success than to employ the armour in launching attacks on the enemy armour.

The traditional desert tactic of making the initial penetration far from the coast where the defences were weakest or non-existent and then attacking the enemy on the inland flank was discarded. The original plan prescribed a two-pronged attack, the main weight of which was to fall on the heavily defended area in the north.

This plan (wrote Montgomery later) was to attack the enemy simultaneously on both flanks. The main attack would be made by 30 Corps (Leese) in the north and here I planned to punch two corridors through the enemy defences and minefields. 10 Corps (Lumsden) would then pass through these corridors and would position itself on important ground astride the enemy supply routes; Rommel’s armour would have to attack it, and would, I hoped, be destroyed in the process. ... In the south, 13 Corps (Horrocks) was to break into the enemy positions and operate with 7th Armoured Division with a view to drawing enemy armour in that direction; this would make it easier for 10 Corps to get out into the open in the north.7

Here we see a prominent and finally decisive role assigned to the corps d’élite of armour (now the X Corps) that Montgomery had announced he would form on the day he took command of the Eighth Army.

The fact that the enemy held Himeimat with its commanding observation of all assembly areas in the south suited the plan in some respects since it would enable the enemy to observe deceptive measures which would simulate an intention to attack in the south. Conversely enemy possession of Himeimat would not have suited a plan for a real “left-hook” operation.

The Eighth Army had acquired a great deal of detailed information about the enemy defences from ground patrols, from air photographs and, in one important locality, from the BULIMBA Operation. Patrols provided little information of what lay beyond the spiked outer fringe of the defence girdle and the approaches to it. The detailed information came mainly from the very skilled Army Air Photograph Interpretation Unit, which produced traces and overprint maps of enemy defences; but so much detail was provided that there was a risk of believing that little had been missed. Enemy forethought, however, enabled many of the inner minefields to be hidden from the alert eyes of the interpreters. These fields were laid chiefly where the low “camel-thorn” scrub was thickest and presented on air photographs a mottled pattern that hid the disturbance of the surface. Wind-drift of shifting sand soon completed the mines’ concealment.

The army’s planning took account of the formidableness of the enemy defences, but even so its picture could not be complete and it could not be aware of the extent to which the girdle of defences was interlaced with strips of mines. The plan, of course, could only be based on overcoming the defences as they were known. They were described in a series of Intelligence summaries produced in the second week of October, which

indicated that from the coast to Deir el Shein the defence system was from 3,000 to 7,000 yards in depth. There were two main defensive belts about 3,000 yards apart often with little between them, but with east-west “dividing walls” of defensive positions connecting the two main north-south belts at intervals of 4,000 to 5,000 yards, and forming a series of “hollow” areas, probably intended for defensive fire tasks, and as traps for attackers, who would be exposed to enfilade fire while in an angle of minefields formed by the junction of a dividing wall with the second belt of defences.

The summaries described the defences near the coast and near the road and railway, which latter were shown to be in considerable depth and strongly developed, and indicated that farther south (in the zone which the 9th Division was to attack) there was a strong buttress position about West Point 23. The second defensive belt ran parallel to the first, along the reverse slope, to Miteiriya. South from the Miteiriya hollow to Deir el Shein there were other strong and extensively wired positions. Southwards from Deir el Shein the defences were less continuous and from Himeimat southwards they were less developed still.

The immensity of the Eighth Army’s onslaught, as Montgomery had conceived it, caught the imagination of the commanders and staff as it was successively disclosed to each command level in strict conformity with a carefully timed program. Montgomery saw to that by personally making the exposition to all commanders from the corps commanders down to the battalion commanders. The men were also to have their imagination fired and their confidence excited to a high pitch when, in their turn, they were to be told by their commanders. An attack in the north by four infantry divisions. A similar attack in the south by the better part of two infantry divisions. Two armoured divisions to break through at dawn in the north; another one in the south. There would be about a thousand tanks (and as many again available to replace them). There would be an opening barrage, so they were told, by close on a thousand guns.

Montgomery’s corps and divisional commanders were first told of his plans for an offensive on 15th September when they were summoned with their chief staff officers to his headquarters to hear him expound his original plan, which he had set out in a memorandum of instructions for the battle signed by him on the 14th. As well as outlining the tactical plan Montgomery’s memorandum contained instructions concerning secrecy, training, and the development of morale. The plan was not yet to be disclosed to anybody else except the artillery commanders; the memorandum was not be copied nor anything committed to paper; and for the present all orders were to be oral.

The operation was to be called “Lightfoot”. It was designed to trap the enemy forces in the defences they then held and to destroy them there. The plan in outline provided that the enemy was to be “attacked simultaneously on his North and South flanks”. The attack on the northern flank was to be carried out by the XXX Corps with the object of breaking into the enemy defences between the sea and the Miteiriya Ridge (part of

which was included in the objectives) and forming a bridgehead which would include all the enemy main defended positions and his main gun areas. (The objectives of the XXX Corps were delineated on a trace. “These,” stated the memorandum, “include the main enemy gun areas.”) The whole of the bridgehead was to be thoroughly cleared of all enemy guns. The main armoured force – X Corps – would be passed through the bridgehead “to exploit success and complete the victory”. On the southern flank the XIII Corps was to capture Himeimat, to conduct operations from there designed to draw the enemy armour away from the main battle in the north and to launch the 4th Light Armoured Brigade round the southern flank to secure Daba, capture the enemy supply and maintenance organisation there and deny him the use of the airfields thereabouts.

The break-in was to be effected in moonlight and supported by a great weight of artillery. For the main break-in, the XXX Corps would employ four infantry divisions – the 9th Australian, 51st Highland, 2nd New Zealand and 1st South African – and one armoured brigade, the 23rd. The New Zealand division’s task would be to capture and hold the western end of the Miteiriya Ridge. The operations of the XXX Corps were designed so that the armoured divisions of X Corps would be able to pass unopposed through gaps made in the enemy minefields and be launched into territory to the west of them. The X Corps would then “pivot on the Miteiriya Ridge, held by its own New Zealand division, and ... swing its right round” until the corps was positioned on ground of its own choosing astride the enemy supply routes. It was “essential for the success of the whole operation” that the leading armoured brigades should be deployed and ready to fight by first light.

Further operations would depend on how the enemy reacted. “The aim in the development of further operations,” wrote Montgomery, “will be based on:–

(a) The enemy being forced to attack X Corps on ground of its own choice.

(b) X Corps being able to attack the enemy armoured forces in flank.

(c) The fact that once the enemy armoured and mobile forces have been destroyed, or put out of action, the whole of the enemy army can be rounded up without any difficulty.”8

A combined operation was to be organised with the object of landing a small force of tanks, artillery and infantry on the coast near Ras Abu el Guruf. (This was cancelled in the second plan.)

To the 9th Australian Division and doubtless to all the other infantry divisions the plan was most inspiriting both in its broad concepts and in many of its details. The operations of Eighth Army so far experienced by the division had seemed to amount too often to “sending a boy on a man’s errand”. The infantry tasks in an army attack had usually consisted of one or two separate attacks on a two-brigade front or less (often much less) to seize an objective which then had to be held with open flanks. Now the division was to take part in an attack to be made by four infantry divisions in line abreast. Previous night attacks had required the

infantry to be out in front at dawn, there with their meagre anti-tank artillery to await the inevitable tank counter-attack. Now the plan required the army’s elite armoured corps to be out in front at dawn. How often, in previous attacks, had narrow breaches been made in minefields, only to be closed by enemy counter-action or sometimes blocked by a single vehicle’s immobilisation. Now the mine-clearing forces had been enlarged and on each axis of advance two gaps would be made in each minefield, and one would be widened as soon as possible to 24 yards.

Some of the commanders of the armour, however, harboured doubts. The detailed planning, as it came to be revealed, took much account of the perplexing problem of minefield clearance; but the problem of the concealed, flashless anti-tank gun had received less attention. The plan was based on the expectation that almost all the anti-tank guns in the main assault region would be first smothered by the infantry night advance, but the armoured commanders were not so sure. It was to be discovered in the battle that in fact there was an anti-tank gun network farther back;9 but even though the armoured formation commanders lacked such complete foreknowledge of what the battle would reveal, they were nevertheless apprehensive that optimism might have prevailed over realistic judgment and that, before the armoured force could reach the enemy supply routes through a heavily defended zone and there invite attack by the German armour, most of its tanks might be shot to pieces. Such apprehensiveness was evident, for example, in an instruction put out for the battle by the 1st Armoured Division, which warned the 22nd Armoured Brigade (which was to debouch near the Australian division’s objectives) that it was imperative that its strength should not be dissipated against the anti-tank guns but be reserved to destroy the enemy armour.

Montgomery himself began to be assailed with doubt that his plan was sound in so far as it aimed to win the battle by relying on his armour to defeat Rommel’s. On 6th October, two weeks and a half before the date set down for the attack, he changed the plan:

My initial plan (he wrote later) had been based on destroying Rommel’s armour; the remainder of his army, the un-armoured portion, could then be dealt with at leisure. This was in accordance with the accepted military thinking of the day. I decided to reverse the process and thus alter the whole conception of how the battle was to be fought. My modified plan now was to hold off, or contain, the enemy armour, while we carried out a methodical destruction of the infantry divisions holding the defensive system.10

Montgomery called the contemplated operations to destroy the enemy infantry in their defences “crumbling operations”. The new approach dealt with the one incompletely answered question in the first plan. “What if the enemy should not attack the armour on the ground it was to take up?” Under the new plan, the enemy armour would not be able to stand by while his infantry was systematically destroyed. Montgomery still aimed,

however, to get the armour out in front. The operation orders soon to be issued were to require the armour to pass through the bridgehead by dawn on the first day and deploy beyond the infantry objectives.

Thus the new plan was not really a reversal of the old. Only a change of emphasis had been introduced, which laid heavier tasks on the infantry. And the notion of “crumbling”, which signified attacking the enemy with infantry to encompass his destruction rather than to wrest ground from him for the tactical advantages thereby gained, was to exert later an influence on the battle with important consequences to the 9th Division.

Montgomery then and later declared that the change of plan sprang from his apprehension that his troops were insufficiently trained for the tasks he had laid upon them. “It is a regrettable fact,” he wrote, in the course of a four-page paper issued to senior staff and commanders down to divisional commanders, “that our troops are not, in all cases, highly trained. We must therefore ensure that we fight the battle in our own way, that we stage-manage the battle to suit the state of training of our troops, and that we keep well balanced at all times so that we can ignore enemy thrusts and can proceed relentlessly with our own plans to destroy the enemy.” That a lesser standard of training was required to fight the battle according to the second prescription rather than the first is not instantly perceptible; but in other respects the original tasks had meanwhile been lightened – the attack by the 4th Light Armoured Brigade on Daba had been cancelled and the original objective for the thrust in the north had been reduced so as to avoid the strong defences in the coast region.

As mentioned the plan was revealed to successive levels of command by a timed program: to artillery commanders on the same day as the divisional commanders and their chief staff officers, to brigade commanders and senior engineer officers on 28th September, to battalion and unit commanders on 10th October, to company, battery and other sub-unit commanders on the 17th, to all officers on the 21st – two days before the battle, and to the men on that day and the next. Nobody was to be told of the plan in advance of the time prescribed for him to be told. From the 21st all leave was cancelled. The area occupied by Eighth Army was then sealed off and nobody was allowed out of it.

–:–

The expansion and large-scale re-equipment of the Eighth Army involved a parallel expansion and reorganisation of the supply services. This was particularly true of base workshops handling the servicing of tanks going forward and the maintenance and return of tanks sent back from the front. Soon after the plan was announced on 15th September small carefully camouflaged and dispersed dumps began to appear close to the front in the forward areas. There were dumps of supplies of all kinds, but mainly of ammunition. So far as possible petrol and ammunition were stored underground. Convoys of trucks delivered their loads in darkness; afterwards the vehicle tracks were obliterated. More than 300,000 rounds of field and medium artillery shells were concealed close to the positions from which the guns would fire when the attack opened.

In the 9th Division’s area 600 rounds per field gun were moved up by night, dug in and camouflaged. Petrol supplies amounting to 7,500 tons had to be dumped forward. All captured German “Jerricans” were called in from the infantry formations and given to X Corps to ensure that its initial reserves of petrol would not suffer the losses through leakage invariably experienced with British containers.

Other diggings appeared, for no purpose evident at the time. Here would be set up the tactical headquarters of the formations. Other diggings again were preparations for the casualty stations and other medical services.11 Provision was made for the evacuation of prisoners of war. Pipe-lines were extended and new water-points established.12

Utmost attention was given to concealment and deception. The intention to attack could not be hidden, but it was hoped that the day and the place could be kept secret. The aim of the “cover” plan was to create an illusion that the army would not be ready to attack until November and that the main attack would then be made in the south.

So far as possible administrative and supply arrangements that could be watched by the enemy espionage network at Cairo and Alexandria were so ordered that wrong conclusions could be drawn, and clandestine arrangements were made for information to reach the enemy that the army would not be ready by October. Leave to Cairo and Alexandria for forward troops was instituted on a considerable scale and was continued up to almost the eve of battle, the last parties selected being (without their knowing it) men to be left out of the battle. So that the stopping of contracts for fresh supplies might not lead to an inference that an attack was about to be launched, such contracts were stopped for a period early in October when no operations were pending, and for that time the whole army went on to hard rations. An air force bombing and strafing program similar to the one that was to precede the real offensive was carried out in September so that when it was repeated in October the enemy need attach no special significance to it. Infantry patrolling was kept general to ensure that no indication was given of a particular interest in any part of the front.

The construction of a dummy pipe-line (with ancillary installations) leading out to the south was undertaken to deceive not only as to the place of attack but as to the time. The pipe-line was visible from Himeimat and the work proceeded at a pace to indicate that it could not be completed by the October moon. Vehicles dragging chains to raise the dust were driven up and down the southern road to simulate heavy traffic serving that region.

Nothing could prevent the enemy’s observing from the air the desert’s changing face or noting the assembly, on its bare floor, of hundreds of guns and tanks and thousands of vehicles. The aim was not to disguise the fact that they were being assembled (rather it was advertised) but

to hide from the air camera their later movement when they would deploy for battle. Early in the planning each unit had to state the number of vehicles it would require for an attack followed by a short advance. The assembly of all vehicles and tanks required was planned and then, to conceal the movement of the immense concourse of vehicles into assembly areas on the day before battle, the planners ordained that by 1st October the number and arrangement of vehicles on the floor of the desert should appear the same from the air as it would on that later day after they had moved. This was achieved by erecting dummy vehicles to the required number and in exactly the places where the real vehicles would be both before they had moved, and after. The dummies were to be so constructed that they would shelter and conceal the real vehicles, which were to be driven into position beneath the dummies Thus, for example, when the armour of the X Corps moved up from the south to assemble in the north for battle, it would leave one set of dummies and come to another, and the tanks’ tracks would be carefully obliterated. Meanwhile a busy simulated wireless traffic would continue to be emitted in the south by the signallers of the inoperative 8th Armoured Division. No change in the number or placing of vehicles would show up on the enemy’s air photographs.

The arrangements made in the 26th Brigade’s area can serve as an illustration of how it was done. Vehicles and dummies equal in number to the total required on D-day were placed in the area by 1st October. All available “A” and “B” Echelon vehicles were brought forward and the balance was provided by dummies. An officer was appointed to control the area and ensure that dummies could not be detected from the air. The dummies were in vehicle pits interspersed among real vehicles, and drivers had to live near them and not with their real vehicles. Vehicles were allowed to move in and out of the area, but it had to be made to appear that the dummies were also moving in and out. When it was the turn of a dummy to move it was collapsed and a real vehicle was run in and out of its pit so as to produce a track plan suggesting that all the vehicles were real. At the end of each day some real and dummy vehicles changed places.

By requiring the X Corps to pass en masse through the four-division front of XXX Corps into enemy territory the plan would superimpose the armour’s approach routes and communications on those of the infantry corps. This required the construction for X Corps of six roads leading up to the assault zone from well in rear and later to be continued on through the enemy’s defended area after it had been captured by the infantry. The six new tracks for X Corps were to be known as Sun, Moon, Star, Bottle, Boat and Hat tracks. The XXX Corps was to use the existing roads up to the existing forward unit areas – on the night and day before the battle the two tracks to the right of the main bitumenised coast road were to be made one-way only routes (i.e. both forward only) – but the 9th Divisional Engineers had to construct four routes from the main road across to the infantry assembly areas on the right of the corps front, whence

also they would be continued on up the axes of advance into the enemy territory when taken. They were to branch left off the main road just in rear of the Tel el Eisa station. These routes – named Diamond, Boomerang, Double Bar and Square tracks – were to be the lines of communication to the infantry in the sector in which the 9th Division was to fight. On the day before the attack all these routes were marked with pictorial signs depicting their names – which were also indicated at night by illuminated signs shining backwards.

From the air the six broad tracks for the X Corps would appear like arrows on the face of the desert pointing from a long way back to the area of assault.13 Therefore, until the last possible moment, work was done only on disconnected parts in the most difficult stretches. The rest of the work was completed almost overnight two nights before the attack.

–:–

“As you train, so you fight” might well have been made the Eighth Army’s motto while it was preparing for battle. The program included special training in critically important aspects of the operation and realistic rehearsal of actual tasks by everybody. The most important tasks were first closely studied and then reduced as far as possible to a drill.

Three problems received specially close study: cooperation in offensive operations between infantry and tanks closely supporting them; clearance of minefields; and ensuring not only that the infantry would go to the right place in the right time in a night attack but that the vehicles bringing up their ammunition and stores afterwards would both be able to get forward and know where to go.

A study of close cooperation between infantry and tanks in attack had begun before the planning for Operation LIGHTFOOT got under way. At the suggestion of Brigadier Richards, battalions of the 9th Division when not in the line carried out exercises with a regiment of the 1st Army Tank Brigade. After a reorganisation of the armoured formations was effected, Brigadier Richards became the commander of the 23rd Armoured Brigade which was to support the 9th Division and other divisions of the XXX Corps in LIGHTFOOT and, in accordance with Montgomery’s instruction that “tanks that are to work in close cooperation with infantry must actually train with that infantry from now onwards”, the training was continued and extended to cover the additional problems of clearing minefields and attacking through them with tanks and infantry in a night attack.

At the direction of the Eighth Army’s Chief Engineer (Brigadier Kisch), a drill for minefield clearance was worked out first (and appropriately) in the armoured corps and then made standard for the whole army. A school of mine clearance was then established. The minefields were the enemy’s main obstacle. Their clearance was the most difficult problem to surmount in the task the Eighth Army had been set. In the main the fields consisted of buried anti-tank mines but were “booby-trapped” at random with the extremely lethal “S” type (anti-personnel)

mines whose prongs protruding from the ground and surrounding web of trip wires were easy to miss. Some fields were mined with buried aerial bombs. The dreadful anti-personnel minefields were less extensive.

The mine-lifting job was done in logical stages. First, the field had to be detected; then its home and far boundaries were established and marked, and a centre line for the lane to be cleared was also marked. Next the outer edges of the lane were marked and the field was cleared of “S” mines Finally the anti-tank mines were lifted and the cleared gap was marked with lights and signs.

Electronic detectors were used for mine detection when available, but they were not always available. Then reliance was placed on highly experienced, skilled and alert – and brave – engineers to “smell” the mines, after which individual mines in a field had to be located by prodding with bayonets.

A reconnaissance party headed by an officer followed the infantry into the attack, reeling out a tape for the working parties to follow, located the home edge of the field, planted there a stake with a rearward shining coloured light and proceeded through the field, stooping and lightly brushing the ground with the backs of the hands to feel for trip wires, and continuing meanwhile to unreel the centre-line tape until the far edge was located, when another stake with a coloured light would be hammered in. Two men, required by the drill-book to be tied to each other to keep them the right distance apart (eight feet), laid parallel tapes on either side of the centre line to mark the outer boundaries of the lane to be cleared. All tapes were pinned to the ground.

Other groups, well spaced and echeloned back to avoid unnecessary casualties from bunching, traversed the field, simultaneously with the lane-edge working parties, to clear the lane of anti-personnel mines, the removal of which required cool nerves and deft fingers. Provided that there were sufficient men, the lane was then cleared of anti-tank mines by parties working from both ends simultaneously towards the centre. Different coloured rearward shining torch-lights on stakes were used to indicate the sides of the lanes and the home boundary of the minefield. Some modifications of procedure were adopted in the battle when it was found that the minefields were much deeper than expected.

Men operating an electronic detector had to stand erect as they swept it from side to side in a circular motion. All other detection work was done by men crawling the full length of the gap, side by side, sweeping lightly with their hands and actually touching their neighbours.

This was the main method to be adopted but other equipment and methods were used to a limited degree, mainly in the armoured divisions and the New Zealand division. The measures taken are summarised in this extract from the 9th Division’s report on the battle.

(a) Hand lifting of minefields by sappers, based on Eighth Army mine-lifting drill.

(b) The Spiked Fowler Roller, which was fitted in front of each track of a proportion of the tanks of some armoured units.

(c) The newly developed “Scorpion” which consisted of a small roller fitted to operate in front of a tank and which could be rotated by an auxiliary engine fitted to the tank. Small lengths of trace chains were fitted to the roller so that when it was revolved the trace chains threshed the ground in front of it thus exploding any mines or booby-traps which lay in the path of the tank. By this means a gap of the approximate width of the tank could be cleared.14

(d) Minefield gaps were marked with the normal gap marking signs for daylight use and by small electric torches by night. The torches were erected on metal stands and were used in horizontal pairs after the style of the gap signs, one colour showing the minefield and therefore danger, whilst the colour alongside showed the gap and safety. These pairs of lights placed at intervals along each side of the gap proved effective. Groups of three lights were used to indicate the near and far edges of the gap and by the use of different colours the various gaps could be indicated. Different coloured lines of lights (shaded from the enemy direction) were also used to mark the routes to the gaps, starting lines and centre lines of units so that by night the battlefield, while remaining unchanged when viewed from the enemy’s direction, appeared as a fairyland of coloured lights when viewed from our side.15

It was appreciated that the mine-lifting tasks to be done in the battle were too big for the number of engineers held on the strength of formations as prescribed by their war establishments. Mine task forces were therefore built up by giving men from other units to engineer units of the assault formation for the battle. Both army engineers and base engineers were called upon. Men from field park companies would in some instances soon find themselves in the van of assault forces. In the 9th Division a company of the pioneer battalion was absorbed into the 2/13th Field Company, doubling its strength.

It was laid down that the armoured formations would be responsible for clearing their own routes forward. Some mine task forces of the armoured formations (but not of those allocated to be employed with or close to the 9th Division) had protective detachments to mop up any by-passed enemy posts that might snipe at mine-clearing parties.

In the 9th Division, the engineers began training for their tasks six weeks before the battle opened, finally carrying out dress rehearsals on minefields imitated from enemy fields shown in aerial photographs. From early September onwards patrols of two to four sappers with an infantry covering party went forward each night to examine some part of the enemy’s minefield. “For the first time in the history of 9 Aust Div RAE specialised equipment was available for an operation,” says the report of the chief engineer of the division. This included Scorpions, described above; pilot vehicles,16 trucks carrying rollers in front which would explode mines; mine detectors; and perambulators, which carried detectors on a framework mounted on bicycle wheels and were pushed in front of gap-clearing parties to find the edge of the field.

A similar if more straightforward battle-drill had to be worked out for the infantry battalions. The ground-work for many of the procedures

that were adopted was done in the New Zealand division. Some of the most acute problems to be solved for a night attack to great depth were to ensure that, despite casualties to key personnel, the attack would be continued in the right direction, at the right pace and for the right distance, that information of progress would get back (not only to keep the formation and army commanders in the picture, but also to enable antitank guns, tanks, ammunition and consolidation stores to be sent forward at the right time) and that vehicles and men to come forward later would get to the right place.

In the 9th Division’s attacks, which were usually planned for two-company fronts, guide parties were provided both at the centre line of the battalion’s axis and on each of the two company axes. The drill ensured that the whole group knew what distance had to be covered, what distance had been covered at each bound and the direction to be maintained. It also covered the marking of the battle centre line both with tapes and with stakes holding rearward shining lights and the establishment, along the centre line, of report and traffic-control centres in direct communication with forward headquarters, both for calling the vehicles forward and for controlling their movement to prevent clustering near minefield gaps before they could be cleared.

As an additional insurance against loss of direction resulting from casualties to officers or others carrying compasses the idea was conceived that anti-aircraft tracer fire could be used to help. On 19th October two Bofors guns 1,000 yards apart were fired out to sea from the 20th Brigade area to test whether they could be safely fired over the heads of the infantry. The idea appeared practical and was approved by the divisional commander. One section of the 4th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment was given the task of firing their guns at intervals along the axis of advance of the assaulting battalions.

The 9th Division’s battle orders prescribed that the capture of each objective would be “reported by the quickest means available and repeated by all the alternative means which exist”. The means included light signals, line and radio telephony, wireless telegraphy and (for emergencies) pigeons.

–:–

“All formations and units will at once begin to train for the part they will play in this battle.” So Montgomery directed in his battle instructions issued on 14th September to outline the general plan. “Time is short,” he continued, “and we must so direct our training that we shall be successful in this particular battle, neglecting other forms of training.” Time was short indeed; and since the 9th Division still had to defend its front, the brigades would have to be relieved and trained in succession. The 26th Brigade was then in reserve, so its preliminary training was put in hand at once.

Intense, rigorous and almost continuous training was instituted for units not in the line with a twofold purpose: teaching what had to be learnt, and making the men hard and battle-fit. They cursed their masters then,

but in retrospect fully approved when, at the time appointed, the realism and purposefulness of the training were revealed to them.

This was supposed to be one of those well-known rest areas (wrote a battalion historian). The troops grinned cynically whenever they heard the words. In a rest area you either dug holes all day and guarded dumps all night or you trained all day and guarded dumps all night. This rest area was different. You trained all day and then you trained all night. Not every day and every night – but almost.17

Battle drills were first taught to companies and sub-units by day and repeated the same night. They were repeated again in whole unit exercises by day and by night. Then infantry units and their supporting arms carried out joint exercises. Finally full-scale and full-dress rehearsals were conducted by brigades and their supporting arms and services, the men performing their long wearisome tasks – including advances for some 6,000 yards – heavily loaded with the full accoutrements of battle; the trucks, loaded with ammunition, bogged as often as not. The rehearsals avoided none of the difficulties. Defences and minefields were laid out exactly as they were expected to be encountered, except that for security reasons all tasks and the defence lay-out were reversed from left to right. The 26th Brigade, for example, which in the real battle would penetrate deeply on a narrow front, then form a firm flank facing right, was required in the rehearsal to advance the same distance and form a firm flank facing left. Thus when each unit entered the battle on the first night, it was to carry out an operation which it had fully rehearsed in detail. And during the battle a comment frequently heard from the men was, “it’s just like an exercise”.

–:–

On the 22nd and 23rd September the 26th Brigade relieved the 20th Brigade in the coast sector. The relieving officers and men told their counterparts in the 20th of the intense training in night attack exercises they had been undergoing and of the tactical plan to which the exercises had conformed. The 20th Brigade men soon found themselves rehearsing night attacks, but to a different tactical plan. They did not guess that this was because they were rehearsing their own different task in the forthcoming battle.

The 24th Brigade, which had had little rest since the brigade’s first attack on Makh Khad Ridge, was relieved on 2nd and 3rd October by a brigade of the 51st Highland Division to afford it a brief spell before the battle. Soon, on the nights 12th–13th and 13th–14th October, the 24th Brigade returned to front-line duty, this time on the coast sector, where it relieved the 26th Brigade which then resumed its training for the biggest operational task it had yet attempted.

From 2nd October onwards each brigade of the 51st Division spent about one week in the line on the left of the divisional front, coming under command of the 9th Division. At midnight on 20th October the command of the southern sector of the divisional front passed to the

51st Division, which was then in the area from which it was to move in to the attack.

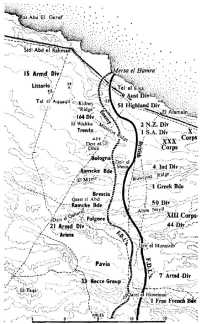

By late October the Eighth Army was organised thus:–

XXX Corps (Lieut-General Leese)

23rd Armoured Brigade Group (Brigadier Richards)

51st Division (Major-General Wimberley)

9th Australian Division (Lieut-General Morshead)

2nd New Zealand Division (Lieut-General Freyberg)

1st South African Division (Major-General Pienaar)

4th Indian Division (Major-General Tuker18)

XIII Corps (Lieut-General Horrocks)

7th Armoured Division (Major-General Harding)

44th Division (Major-General Hughes19)

50th Division (Major-General Nichols)

X Corps (Lieut-General Lumsden)

1st Armoured Division (Major-General Briggs20)

10th Armoured Division (Major-General Gatehouse)

8th Armoured Division (Major-General Gairdner21) which comprised only a headquarters and some divisional troops. Because it was then incomplete its formations and units had been transferred to other formations.

The army had more than 220,000 men and would muster on the day of battle more than 900 tanks and about 900 field and medium guns.

In the Axis forces there were now four German and eight Italian divisions in Egypt. In the Armoured Army of Africa were the Africa Corps (15th and 21st Armoured Divisions), 90th Light Division, 164th Light Division and the Ramcke Parachute Brigade. In the three Italian corps – X, XX, and XXI--were the 132nd (Ariete) and 133rd (Littorio) Armoured Divisions, the 101st (Trieste) Division (motorised), the 185th (Folgore) Division (parachute troops), and the 17th (Pavia), 25th (Bologna), 27th (Brescia) and 102nd (Trento) Divisions (infantry). The Young Fascists Division garrisoned the Siwa oasis and the 16th (Pistoia) Division was just across the Libyan frontier at Bardia. The Axis forces were about 180,000 strong, of which a little less than half were Germans; there were some 77,000 other Italian troops elsewhere in North Africa. They had more than 500 tanks, of which more than half were Italian.

The enemy’s forward positions were now held, from the north, by XXI Corps (164th Light, Trento and Bologna Divisions and two battalions of the Ramcke Brigade); then X Corps (Brescia, Pavia, Folgore Divisions and two battalions of the Ramcke); the 33rd Reconnaissance Unit was on the southern flank. The 15th Armoured and Littorio Divisions were behind XXI Corps and the 21st Armoured and Ariete Divisions behind X Corps.

In reserve along the coast were the 90th Light Division and the Trieste Division about Daba, and the 288th Special Force and 588th Reconnaissance Unit in the Mersa Matruh area.

In each corps sector of the front German units were interspersed with Italian so that for their defence girdle (to abuse the metaphor of Brigadier Williams,

Montgomery’s senior Intelligence officer, by mixing it with another) the German command had fashioned a corset strengthened with German whalebones.

Field Marshal Rommel had been in poor health for some time. When the battle of Alam el Halfa was fought he had been so ill that he could scarcely get in and out of his tank On 22nd September he handed over his command to General Stumme, who had been commanding an armoured corps in Russia and earlier had commanded one in Greece, and left next day for Europe to recuperate, having first told Stumme that he would return if the British attacked. The Africa Corps had meanwhile been placed under the command of General von Thoma, also from the Russian front.

Appreciating the delay that British air power could impose on the movement of armour, Stumme and von Thoma decided – not long before the battle – to split the armour and hold it behind the lines in two groups, one north, one south, so that quick counter-attacks could be launched in either sector without a long approach march. It was thought likely that an attack by moonlight would be made in October.

Early that month the enemy was trying to guess where the attack would fall. It seemed unlikely that it would be in the far south. On 7th October the diary of the Armoured Army of Africa recorded that the probable directions of the British attack were (a) along the coast road, (b) about Deir el Qatani, (c) at and south of Deir el Munassib. Next day, however, a new appreciation predicted that the main attack would fall between Ruweisat and Himeimat, but that there would also be attacks in some strength astride the coast road.

Although Montgomery’s second plan was a fundamental change from the first in that the process of destruction of the enemy had been “reversed”, the orders to which the battle was actually fought bore, superficially at least, a remarkably close resemblance to the original plan. The XXX and XIII Corps were still required to deliver two simultaneous heavy blows at the enemy by moonlight – the heaviest and decisive blow to be aimed in the north – and the armour was still to debouch. Both infantry attacks would start at 10 p.m. on 23rd October and were designed to overrun the enemy’s minefields and gain possession of his defences, including the field gun areas, so as to facilitate the passage of the armoured formations to the enemy’s rear before dawn. Infantry “crumbling” operations would be developed on subsequent days in attacks from north and south to pinch out the enemy forces holding the centre. Depending on the progress of the battle, orders might also be given to pinch out the German forces between the northern flank and the sea.

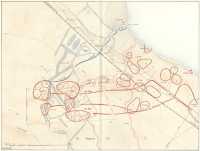

The plan required the XXX Corps to attack with four infantry divisions forward – from right to left, the 9th Australian, the 51st Highland, the 2nd New Zealand and the 1st South African – and to take its final objectives by 3 a.m. so that the armour would be able to pass through before dawn. The final infantry objectives were depicted by a map-line (running, from the right, at first due south, then about south-south-east then about east-south-east) which was to be known in the army plan as the Oxalic line. When the infantry objectives had been taken the X Corps was to proceed through two bridgeheads and up to the Oxalic line and then advance beyond it by two bounds – the first bound (Pierson) being about 2,000 yards forward of the final infantry objectives – to secure on the second bound the high ground about Tel el Aqqaqir and establish there, with tanks, motorised infantry and anti-tank guns, a firm base astride the enemy’s communications to his forces in the south. The object

XXX Corps’ objectives, 23rd–24th October

was to force the Axis armour to attack the anti-tank guns and armour of X Corps.

In the north of the XXX Corps front, in which the 9th Division was most interested, the 2nd Armoured Brigade was to lead the armoured advance to the first bound, whereupon the 2nd Motor Brigade would come up to protect its flank for the move to the second bound.

In addition to the four infantry divisions the XXX Corps would have under command the 23rd Armoured Brigade Group of four tank regiments to give close support to the infantry battalions in the assault and later crumbling operations. The 9th Australian, 1st South African and 51st Highland Divisions each had a tank regiment attached for the operation. The wish of the New Zealanders to have their own armour under command had been granted and the 9th Armoured Brigade (with 122 tanks) had been incorporated in the division, which then comprised two infantry brigades (the 5th and 6th) and one armoured brigade.

The New Zealand division had been nominated as a component of the elite X Corps. Though under command of the XXX Corps for the opening assault, the division was intended to operate later with the X Corps.

In the south, the XIII Corps was to employ the 44th Division to make two gaps in the old British minefields (known as January and February) of which the enemy had retained possession after the Alam el Halfa battle, and then to pass the 7th Armoured Division through to the enemy’s rear, where it was to operate as a threat so as to keep the German armour stationed in the south from moving north, but was to avoid becoming heavily committed. On the right of the main corps operation the 50th Division was to operate in the Munassib depression, and on the left the 1st Free French Brigade was to attack for Himeimat.

The most vulnerable part of the northern bridgehead would be its deep right flank, which would face the most fully developed defended area of the whole Axis front, covering the main road, to the north of which strong artillery was ensconced in the dunes near the coast. The selection of the 9th Division to mount the attack on the right of the line, though not made for that reason alone, was none the less a compliment. The 1st South African Division had similar responsibilities on the southern flank of the corps’ front but if successful would not have an open flank, since the new front would link with the existing front where it protruded on the south side of the area the South Africans were to attack.

The additional troops placed under the command of the 9th Division for the operation included the 40th RTR, and the 66th British Mortar Company with eighteen 4.2-inch mortars;22 and in support for certain periods were to be six troops of corps field artillery, the 7th Medium Regiment and a battery of the 64th Medium Regiment.

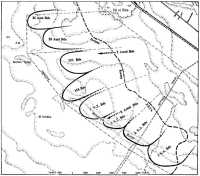

The division’s tasks were to capture an area of the enemy’s defences about 6,000 yards deep and 3,300 yards wide (whose western boundary was the 867 grid line) so as to facilitate the passage of the X Corps through the bridgehead,23 to exploit westward from the objective to Trig 33, and to form a firm flank facing north. About 3,000 yards separated the division’s forward defended localities from the foremost enemy minefields. The final objective of the division was almost three miles and a half west of the wire at Point 23, where the enemy defences would be first encountered.

One of the problems was to maintain the momentum of an advance which would have to penetrate for such a distance through heavily mined and strongly held defences developed in depth. This was tackled by phasing the attack and, on the 9th Division’s but not on all other fronts, by using fresh troops for successive phases. The XXX Corps attack was to be made in two phases; in the first phase the “Red Line”, about 3,700 yards from the final objective, would be captured. For the second phase, start-lines would be laid in territory wrested from the enemy in the first phase. In the divisional plan the two phases were again each subdivided into an intermediate and a final objective, making in all four objective lines to be

taken in succession. The battalions that were to open the assault were to take the first two objectives, whereupon fresh battalions would pass through to take the last two. Each battalion except the 2/17th decided to use two companies to take its first (or intermediate) objective, passing through two fresh ones to take the final objective. As each company took its objective, it was to remain on it and develop it for defence. Thus momentum was to be achieved with fresh troops coming through in four waves. The first phase of the assault was to be made with three battalions, the second with two, the first phase being in greater strength to make sure that the initial penetration could be firmly held as a base from which to launch the second phase.

The division’s attack was to be made on a two-brigade front with, on the right, the 26th Brigade (Brigadier Whitehead) less the 2/23rd Battalion, and on the left the 20th Brigade (Brigadier Wrigley). The 24th Brigade (Brigadier Godfrey) would continue to hold the existing front near the coast.

The 26th Brigade was to have under command a composite force which was to hold the gap between the right rear of Whitehead’s open right flank, as it would rest when the brigade faced north on completion of the attack, and the left flank (near the road and railway) of the defences that the 24th Brigade would continue to hold. The composite force was to be commanded by Lieut-Colonel Macarthur-Onslow24 and comprised a company of his own machine-gun battalion, a company of the pioneer battalion, a squadron of the divisional cavalry and anti-tank detachments.

As the 26th Brigade, on completion of its assault, would have to form a long firm front on the northern flank as well as a front to the west, it was given a narrower front to attack than the 20th Brigade. The 26th Brigade was to attack with one battalion up in both phases, the 20th with two up in the first phase, one in the second. The latter battalion (the 2/13th) would thus have to attack on the widest front and to the full depth of the divisional objective.

The role of the 24th Brigade was, in addition to holding the existing defences in the coast region, to carry out a diversionary operation beginning at Zero and designed to draw enemy artillery fire on to its area, and to maintain one battalion at call as a divisional reserve.

The 2/23rd Battalion and the 46th RTR, which were to be detached from their parent formations, were detailed as corps and divisional reserve, with perhaps a semi-mobile role. They bivouacked and trained together for a week before the battle. The 9th Divisional Cavalry Regiment (less the squadron with the composite force) was another mobile divisional reserve.

The 40th RTR was to be placed under command of the 20th Brigade. The tanks were to move along the divisional centre line until the enemy’s main forward positions had been passed and were then to move southwest in support of the 2/13th Battalion in their attack on the enemy’s

positions about 2,000 yards south-west of Trig 33 and in their final exploitation to Trig 33.25

The 40th RTR was then to rally to the rear of the objective and come under command of the 26th Brigade but was not to be employed by that brigade without reference to divisional headquarters “unless the situation will not permit this, in which case the action will be reported immediately”.

The rate of advance was to be 75 yards a minute to the enemy minefield and thereafter 100 yards in 3 minutes. These timings (in adhering to which the infantry were first given exhaustive practice) were set to enable the foremost troops to “lean” on the artillery barrage. At Zero plus 55 minutes there would be a pause of 15 minutes to pass companies through, and at Zero plus 115 a pause of an hour to pass the battalions through to take the second objective. The signal for the opening of phase two would be the quickening of the rate of artillery fire. At Zero plus 235 there would be another pause of 15 minutes to pass companies through; at Zero plus 310 minutes the infantry should reach the final objective.

Montgomery’s battle-plan laid great store on the shock effect of a barrage from the army’s massed artillery. No more painstaking work was done before the battle than in the preparation of the fire-plan. All guns supporting the infantry assault had to move forward to new positions for the battle, which had to be chosen and surveyed, and because the guns could not range on targets beforehand, the setting for every gun for every target to be engaged in the battle had to be calculated from data.

Great though the army’s array of artillery was, there were not sufficient guns for an efficient creeping barrage across the whole assault front. The program therefore provided for successive timed concentrations on known targets, though with creeping barrages on areas where specific targets were not indicated. Starting at 20 minutes before the Zero hour for the infantry advance, there was to be a bombardment of the enemy’s gun-sites for 15 minutes. During that time the divisional artillery would be under corps command. At Zero it would come under divisional command and fire concentrations continuously (but at varying rates of fire) for the five hours and ten minutes allowed for the infantry to take their objectives, with pauses in lifts to correspond with the pauses prescribed for the infantry advance to allow following companies and battalions to pass through those in front and resume the advance.

Two searchlights were established at accurately surveyed points behind the corps artillery and were to send up stationary beams on the night of the battle. These were intended to serve two purposes: first, to indicate two known points from which position could be plotted by re-section – for this they proved to have been too close together and also too far back to be plotted on most of the maps carried forward; secondly, to indicate the commencement of phases of the artillery plan (which could be useful if a synchronised watch were destroyed) by swinging the beams inward at the moment of commencement.

Throughout the battle the bringing down of defensive artillery fire was to be greatly simplified and speeded up by dividing the enemy’s territory into small areas each of which was labelled with a code name – Galway, for example, Broome, Wexford, Fremantle and so on. As soon as a call for attention to one of these places was sent back to the guns, several regiments would promptly concentrate their fire on it.

The main task of the engineers was to see the infantry safely through the minefields. The 2/7th Field Company was placed in support of the 26th Brigade and the augmented 2/13th Company in support of the 20th. The 2/3rd Company had the tasks of preparing, marking and maintaining traffic routes. Each company in support of an assaulting brigade had to provide detachments with each forward infantry company, provide and fire Bangalore torpedoes, make and mark gaps in the enemy minefields along the axis of advance, widen these gaps to 24 yards, make more gaps as required, and also assist the infantry to lay Hawkins mines.26

On the last few nights before the attack sappers moved out over the axis of advance dealing with all isolated minefields east of the main ones. In this period 203 mines were disarmed but left in position. As a result of this preparatory work there was a clear area right up to the start-line, and on the night of battle the mine-clearing parties had to deal only with the main fields.

The division was to go into battle better armed than ever before. The anti-tank defence showed the greatest improvement. The 2/3rd Anti-Tank Regiment had 64 6-pounder anti-tank guns – really first-class weapons for their task – and there was a good supply of the Hawkins antitank mines which could be quickly and easily laid. Most battalions furthermore had eight 2-pounders in their anti-tank platoons. The 9th Divisional Cavalry had 15 Crusader tanks, 5 Honeys and 52 carriers.

The infantry were much stronger in automatic weapons than ordained by war establishments at the beginning of the war. On the one hand there were the re-introduced machine-gun platoons, with 6 guns per platoon; on the other, the many salvaged weapons. There were 71 Spandau machine-guns in the division – the 2/3rd Pioneers had no fewer than ten-63 Bredas of calibres ranging from 6.5 to 47-mm, 15 81-mm mortars, 5 Besa machine-guns, and other weapons.

On the eve of battle the strength of the battalions ranged from 30 officers and 621 others to 36 officers and 740 others; the war establishment was 36 officers and 812.27

The draft of reinforcements dispatched from Australia on Morshead’s representations had arrived on 10th October, but it was decided, having regard to the standard of earlier drafts, that there would be insufficient

time before the battle began both to harden them sufficiently after the long sea voyage and to train them to a proper standard for battle.28

–:–

When everything had been prepared and all had been trained, it remained to reveal the plan first to the leaders and then to the men and to explain their individual tasks in it. The briefing of commanding officers, and later of company commanders and junior leaders, was carried out at divisional headquarters on an accurate large-scale model of the ground which had been made by the engineers and kept guarded in a building at headquarters.

“Morale is the big thing in war,” the army commander had declared, in his original instructions for the battle.

We must raise the morale of our soldiery to the highest pitch; they must be made enthusiastic, and must enter this battle with their tails high in the air and with the will to win.

The disclosures of the plan stage by stage downwards were made occasions for evoking the enthusiasm for which Montgomery was striving. Morshead expounded the plan to his commanding officers on 10th October and in the address he gave before he explained the operational tasks there were many echoes of Montgomery’s sentiments and expressions.

It will be a decisive battle (Morshead wrote in his notes for the conference), a hard and bloody battle and there must be only one result. Success will mean the end of the war in North Africa and an end to this running backward and forward between here and Benghazi. ...

No information about the operations to be disclosed to anyone likely to be taken prisoner. ... No information therefore to be given to anyone in 24 Brigade.

Wednesday 21st October and Thursday 22nd October will be devoted to the most intensive propaganda to educate attacking troops about the battle and enthusing them. Tell them that if we win, as we will, turning point of the war. ... We must go all out and every man give completely of his best. No faintheartedness. Imbue with fighting spirit.

We must go into the battle with our heads high and the will to win ... it will be a killing match. ... If you have anyone you are not sure of, then don’t take the risk of taking him in. Give him some job other than fighting.

We must all apply ourselves to the task that lies ahead, work, think, train, prepare, enthuse. We must regard ourselves as having been born for this battle.

Montgomery himself, in two conferences held on successive nights three or four days before the battle, addressed all senior officers and commanding officers in the army (who were forewarned not to smoke in his presence) about his plan, his reasons for changing it, the aim of the initial assault (“fighting for position and the tactical advantage”), the “dog-fight” – or “crumbling” operations – (which could last for more than a week), the army’s “immense superiority in guns, tanks and men”, the need to sustain pressure in a battle in which they could outlast the enemy, the importance of morale and the way to get it. As these men sat before Montgomery – these down-to-earth commanders to most of whom he had been perforce a distant and somewhat enigmatic figure – as they listened to his precise

and clipped but confident speech and perceived his mastery of his subject and the occasion, as they heard from him how strongly the odds of battle were weighted in their favour, as they learnt that this attack was not to be one to be made by two brigades or so but one in which the whole army’s forces would be arrayed, they developed instantly a strong confidence in the army commander himself and in his plan.

Thus enthused the commanding officers addressed the men in their units a day or two later, and read to them Montgomery’s personal message in which he said (with a suitable injunction to the “Lord mighty in battle”) that the Eighth Army was ready to carry out its mandate to destroy Rommel and his army, and would “hit the enemy for ‘six’ right out of North Africa”.29 That the men were inspirited and imbued with a confidence they had never before experienced, there could be no doubt. Emotionally charged anticipation was evident when in some instances they began chanting army songs, old and new, as they were moved off in trucks to their pre-battle assembly areas.

One aspect of the plan troubled Morshead: that the infantry to make the initial assault, for which the start-lines were to be laid in no-man’s land, would have to move out the night before to an area near their forming-up places which was under enemy observation by day and would have to spend there a whole day out of sight in shallow slit trenches. He directed that all commanders should be warned of the possible lowering effect on morale.

On 10th October General Leese, after sounding out General Freyberg and finding him agreeable, had written to Generals Morshead, Wimberley and Pienaar to tell them that he wished to advance Zero hour from 10 p.m. to 9.30. Morshead had opposed this. He wrote:

The troops will have lain “doggo” in slit trenches all day. I cannot conceive anything psychologically worse than such solitary confinement in a tight-fitting, grave-like pit awaiting the hard and bloody battle. There must be some relaxation before the fight.

To avoid giving the show away to the air these troops will not be able to emerge until close on 1900 hours. Then they have dinner – in the semi-darkness – and they do not want to be rushed off as soon as they have eaten. During the day they will have been ungetatable for final instructions and advice – however long and thorough the preparations there are inevitably those very last instructions which a platoon commander gives to the whole of his platoon. All this could be done by 2030 but 2100 would be preferable as it would avoid any chance of last minute rush and excitement. Then we have the approach march of two miles and it will take up to an hour by the time the battalions are in position on their start-lines.

To sum up, we will be demanding much of our men and we want them to start off in a proper frame of mind; we could be ready by 2120 hrs but I would much sooner have the extra 20 mins up my sleeve. This would further ensure getting A Echelon vehicles forward from Alamein in time.

In the event the infantry advanced at 10 p.m.

All day on the 23rd October the harsh sun and the flies tormented the restless assault troops in their slit trenches. By midday, the 2/17th

23rd October

Battalion diarist noted, the men were getting unsettled and it was impossible to keep them under cover in their cramped positions.

Men were confident and ready for job ahead (he wrote). Every man in the battalion knew his job and just what was required of him. No matter what happens or who gets hit there will be someone who can take his place and do his job. Our men are certainly entering this action with the “aggressive eagerness” required by the army commander.

Sprawled across the landscape farther back were others, waiting to move forward. There was scarcely any movement on the face of the desert until late afternoon when suddenly it became alive with vehicles emerging from their camouflage and lining up to join at the prescribed time the columns of traffic that had suddenly filled the roads. For 30 miles or more behind the forward defences, vehicles hurried eastwards along every road or track, old or new, leading to the front, in continuous parallel streams.

So, as the sun was setting, the Eighth Army moved to its battle stations, the 9th Australian Division on the right, then the 51st Highland, 2nd New Zealand, 1st South African and 4th Indian Divisions;30 coming up behind these the 1st and 10th Armoured Divisions (and with the latter the 1st and 104th RHA, who had been with the 9th Division in Tobruk) – many of their units bearing names with an illustrious record in British military history; then farther south, the 50th and 44th British Divisions, the former including a Greek brigade and behind them the 7th Armoured Division – the “Desert Rats” – and on the left of the line the 1st Free French Brigade Group. The call to the battle was a roll-call of the Empire, that grand but old-fashioned “British Commonwealth of Nations”,

fighting its last righteous war before it was to dissolve into a shadowy illusion. And it was a summons to which expatriate forces of oppressed nations had responded, freely choosing to fight alongside.

That night General Morshead wrote to his wife:–

It is now 8.40 p.m. and in exactly two hours’ time by far the greatest battle ever fought in the Middle East will be launched. I have settled down in my hole in the ground at my battle headquarters which are little more than 2,000 yards from our start-line. I have always been a firm believer in having HQ well forward – it makes the job easier, saves a great deal of time, in fact it has every possible advantage and I know of no disadvantage. At the present time I can see and hear all the movement forward to battle positions--it is bright moonlight, tomorrow being full moon. ...

A hard fight is expected, and it will no doubt last a long time. We have no delusions about that. But we shall win out and I trust put an end to this running forward and backward to and from Benghazi. ...