Chapter 6: The Struggle for the Ridges

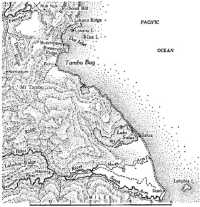

THE capture of Mubo enabled General Savige to press nearer Salamaua, which he regarded as his ultimate goal. The airfield, the isthmus and the peninsula could now be seen from several high points along the Allied front. But although the 17th Brigade had fulfilled its immediate task, the 15th Brigade had been unable to capture Bobdubi Ridge. Savige now ordered Brigadier Moten to exploit north towards Komiatum and northeast towards Lokanu; and Brigadier Hammer to carry out his original task.

As early as 3rd July Savige had warned his brigade commanders about a possible “exploitation phase” to follow the Mubo fight. A day later he sent General Herring a plan asking for an extra brigade which could be used to control the Wampit and Watut River Valleys in place of the 24th and 57th/60th Battalions which could then rejoin the 15th Brigade. He suggested that, “although it may not be intended to attack Salamaua ... action should be taken to isolate the garrison and prevent them receiving further supplies or reinforcements by land”. He considered that this could best be done by harassing the Lae–Salamaua coastal track from a battalion base west of Malolo.

Herring’s view of all this forward planning was expressed later: “There is a great need in war as in other things for first things first and not worrying too much about the distant future. You cannot exploit until you have broken through.” He decided that it was time to apply the brake, and on 11th July informed Savige that it was not considered desirable at that time to lay down a policy regarding Salamaua and that the role of the division remained “to drive the enemy north of the Francisco River”. Politely, however, he did request an outline plan for the capture of Salamaua. Not knowing that Lae was to be a goal before Salamaua, Savige was at some disadvantage in framing the plan which he sent to Herring on 17th July. It provided that the Australians would attack from the North-west, west and South-west towards the airfield and Samoa Harbour, while the Americans secured the south bank of the Francisco River from Logui 2 to the first bend of the river. The combined force would then capture the isthmus and peninsula.

While Savige was busy with these plans, Herring was busy ensuring that Salamaua should be a means of helping the drive to the north. The problems of today, however, pressed more urgently upon the commanders and staffs of New Guinea Force and the 3rd Division than did the problems of the future. The main one was supply. Because of its distance from the coast, the 3rd Division had to be fed mainly from the air, an inaccurate and expensive method. The problem became more burdensome as it became necessary to build up reserve dumps for the operations against Lae. Herring considered that it would be very difficult, if not impossible,

to maintain any further units in the Salamaua area unless they were based on the coast. Savige’s outline plan for the capture of Salamaua, involving the use of an additional brigade, was therefore pigeon-holed in Port Moresby.

The immediate and practical problem facing Herring was how to establish a coastal base whence he could supply the main part of the 3rd Division and bring more artillery against the enemy. Early in July General MacArthur was in Port Moresby. Like other Australian leaders who had served in the Papuan campaign Herring had got to know MacArthur well. On 3rd July he had conferred with him at GHQ and obtained permission to use at least one other battalion of the 162nd Regiment for the coastal move. Herring then summoned General Savige, and General Fuller of the 41st American Division, to Port Moresby, where on 5th July Herring discussed with them his plan to move a battalion of the 162nd Regiment along the coast to Tambu Bay and to install guns there. Himself a gunner, Herring realised that Tambu Bay was the only possible site whence the guns could support the 3rd Division and shell Salamaua. They were of no use at Nassau Bay and they could not be dragged forward via Mubo. As Savige’s headquarters were a long way from the coast and as Fuller was responsible for supplying both MacKechnie Force under Moten and the troops who would move up the coast, Herring decided that the coastal move should be under Fuller’s command. This decision about command was apparently not clear to Savige, who made “brief notes” of the conference and wrote of the new troops from the 162nd Regiment who were soon to arrive at Nassau Bay: “These troops then under my command. ...” Of the proposed move against Tambu Bay and the high ground overlooking it he wrote: “Operations would be directed by 3rd Aust Div.”

On receipt of a signal from Moten that conditions at the Nassau Bay beach-head were chaotic, Savige signalled Herring after his return on the 6th suggesting that Fuller should consider replacing MacKechnie. On the same day the first company of the American III/162nd Battalion, selected to establish an area at Tambu Bay for the guns, arrived at Nassau Bay. Major Archibald B. Roosevelt, the battalion commander, arrived on the 8th with another company; the remainder of the battalion assembled at Nassau Bay by the 12th.

Fuller had no doubts about the decisions of 5th July. On the 11th he issued a “letter of instruction” to his artillery commander, Brigadier-General Ralph W. Coane, who had been chosen to lead the American advance up the coast. Coane would “have command of all troops in the Nassau Bay–Mageri Point–Morobe area,1 exclusive of MacKechnie Force”, and would “be prepared to conduct operations north as directed by GOC New Guinea Force, through this headquarters”. “Coane Force” would be created on 12th July. Thus, when the regimental commander, MacKechnie, returned from Napier to Nassau Bay on 14th July he found

that two-thirds of his former command had been assigned to an artilleryman.

On 12th July Savige began to have misgivings about the command situation and repeated to Herring a signal from MacKechnie to Moten stating that Fuller had instructed MacKechnie that Roosevelt’s battalion was no longer under MacKechnie’s command but responsible directly to Fuller himself. This appeared absurd to Savige who was not yet even aware of the formation of Coane Force. Accordingly he asked for definite instructions clarifying the command of American troops in the Nassau Bay area and stated that dual control would cause confusion. Herring that day signalled “for clarification of all concerned all units Mack Force are under operational control of 3 Aust Div”.

Savige chose to believe that this signal meant that the 3rd Division commanded all troops of MacKechnie’s 162nd Regiment – not merely MacKechnie Force. Herring, however, obviously meant MacKechnie Force. Had the ambiguity been overcome at this stage, some disagreements and difficulties which temporarily marred Allied efficiency and the relationships between the Australian commanders in New Guinea would not have occurred.

Trouble soon began. Savige placed Roosevelt under Moten’s command for his northward move, but, replying to a signal from Moten, Roosevelt signalled on 14th July:

Regret cannot comply your request through MacKechnie Force dated 14th July as I have no such orders from my commanding officer. As a piece of friendly advice your plans show improper reconnaissance and lack of logistical understanding. Suggest you send competent liaison officer to my headquarters soon as possible to study situation. For your information I obey no orders except those from my immediate superior.

Having sent this billet-doux to the startled Moten, Roosevelt then reported to Fuller:

I received orders by 17 Aust Bde that I was assigned to 3 Aust Div. I also received orders from 17 Aust Bde to perform a certain tactical mission and have informed them I am under command of 41 Div and will not obey any of their instructions. If you are not in accordance with this action request that I be relieved of command III Bn. In my opinion the orders show lamentable lack of intelligence and knowledge of situation and it is possible that disgrace or disaster may be the result of their action.

On 14th July Savige decided to bring matters to a head. He signalled MacKechnie and Roosevelt (and repeated the signal to Herring, Moten and Fuller) that New Guinea Force’s latest instructions clearly indicated that Roosevelt’s battalion was under the command of MacKechnie Force which was under command of Moten for the time being. Roosevelt replied: “I do not recognise this signature. I take orders only from my commanding general 41 US Div and will hereafter be careful to certify his signature.”

Savige then wrote to Herring, stating that

a confused and impossible situation has now arisen which makes it impossible to coordinate control of operations. ... The position as understood at this

headquarters is that the Roosevelt combat team has been placed under operational control of 3 Aust Div for employment on the coast north of Nassau Bay. ... Roosevelt now refuses to obey the orders issued by MacKechnie. ... It has now become a matter of most urgent operational necessity that clarification of operational command of Roosevelt combat team be made and that Roosevelt be informed accordingly by 41 US Div.

The next step in this confused situation was that on 15th July MacKechnie telephoned to Moten a message sent from Fuller to Coane on the previous day and stating: “Roosevelt is not part of Mack, is not under comd 3 Aust Div or 17 Aust Inf Bde. ... Until such time as this HQ informs you to the contrary you will comply with letter of instruction given to you. Confusion due to 3 Aust Div and 17 Aust Inf Bde not having received copy of letter of instruction due to communication difficulties.” MacKechnie also signalled Moten on the 16th apologising for Roosevelt’s messages, speaking warmly of Australian cooperation and saying: “I trust you will recognise the difficult position in which Roosevelt has been placed due to confusion in command situation.”2

In his earnest attempt to maintain cordial Australian-American relations and to seek a formula satisfactory to Australians and Americans Herring had the ill-fortune to have his orders misunderstood by his Australian divisional commander. The decision to establish the two commands in the battle area was a logical one in the circumstances but it was surprising that there should have been such a sorry period of doubt about who was commanding what. A report from his liaison officer at Nassau Bay, Major Hughes, finally convinced Herring that further clarification was necessary. Hughes signalled on 15th July: “Utter confusion exists as to command of III/162 Bn.” On the same day therefore Herring signalled Savige that “with view to straightening out control US forces” he had conferred with Fuller’s chief of staff, Colonel Sweany. The signal continued: “41 Div desires that MacKechnie retain control of American troops moving inland and agrees that this Force should operate under operational control of Moten as in past. 41 US Div has sent Brig Coane to control ops for coastwise operations. In view of rapid changing situation this force forthwith under operational control of 3 Div.”

Fortified with this clarification Savige on 15th July signalled Coane, Moten, MacKechnie, Herring and Fuller concerning Coane Force’s task. This would be to establish a secure bridgehead at Tambu Bay by moving companies north along the coast, to land the remainder of Roosevelt’s battalion and the artillery when the bridgehead was secure, and to engage artillery targets in the Komiatum and Bobdubi areas. Coane’s ultimate task would be to advance along the coast and secure the general line from Lokanu 1 to Scout Hill. Coane was ordered to maintain close liaison with Moten, and Captain Sturrock3 of Savige’s staff was sent to Coane’s headquarters as liaison officer.

Savige again flew to Port Moresby on 19th July to confer with Herring’s staff and the Americans about the use and control of artillery, the regrouping of forces, details of proposed operations, and the problem of supplies. In order to remove any lingering American doubts about who was in command in the operational area Herring on the 23rd issued an instruction which stated:

3 Aust Div has command of all troops north of inclusive Nassau Bay and inland from those places with the right to effect such regrouping of forces in this area as it may from time to time consider necessary.

Thus apparently ended a period of confusion of command, an unnecessary period, annoying particularly to those subordinate commanders who received conflicting orders from two sources. This conflict of command caused the very irritation which Herring was so anxious to avoid and which was so apparent in Roosevelt’s remarkable signals.

Herring also ordered that “as soon as required by 3 Aust Div” Coane would become CRA, 3rd Division.4 Until then Coane would make available to the 3rd Division Colonel William D. Jackson and such artillery staff as would be necessary to carry out artillery control and planning. Herring would provide a brigade major and a staff captain for Jackson. On his return from Port Moresby Savige had already offered Coane his choice. Coane had replied that he had been designated divisional artillery commander and would continue to command Coane Force.

Meanwhile the advance up the coast continued. On 10th July an American patrol skirmished with the Japanese south of Lake Salus. Well ahead of the Americans two of Captain Hitchcock’s Papuan platoons were patrolling between Lake Salus and the lagoon south of Tambu Bay while the third platoon patrolled west of Lake Salus.5 MacKechnie had already instructed Hitchcock to push north, clear Japanese pockets of resistance, capture the high ground overlooking Dot Inlet by 15th July, and

establish outposts on Lokanu Ridge and Scout Hill. On 12th July MacKechnie told Hitchcock that future operations depended on the results of his reconnaissance in the Lokanu 1 and Scout Camp areas. Again on 14th July MacKechnie signalled: “On arrival at Tambu Bay area you will recce the beach to ascertain a suitable exit for artillery and also to locate gun positions from which targets on Salamaua Isthmus and Komiatum can be reached.”6 Hitchcock was able to report on the same day that the natives said that Tambu Bay and Dot Inlet were occupied by the Japanese.

A company from the II/162nd Battalion landed unopposed on Lababia Island on 15th July and found there an Australian signaller, Sergeant Parmiter,7 who had volunteered to establish a wireless spotting station and report enemy movement.

Next day, as Roosevelt assembled on the beach for the move north, Hitchcock reported that the Japanese had an observation post on the north side of the lagoon and another on Dot Island; and that natives reported 200 Japanese at Boisi and the remnants of the Japanese Nassau Bay force digging in on the ridge west of Lokanu 1. The advance to Tambu Bay began on the 17th when two companies, guided by the Papuans, were ordered north by an inland track known to the Papuans and a third by the coastal route.

Next day Major Thwaites’8 battery of the 2/6th Australian Field Regiment arrived at Nassau Bay from Buna. By 20th July four 25-pounders were in position at Nassau Bay pending their movement to the north of Lake Salus where they would support the advance; two batteries of the 218th American Field Artillery Battalion with eight 75-mm guns were north of Lake Salus; and one battery of the 205th American Field Artillery Battalion with four 105-mm guns was south of the lake. The artillery was busy registering the Lokanu 1, Boisi, Dot Island and Buiambum areas on 20th July.

Savige hoped that Coane would secure Tambu Bay and then occupy Scout Hill and Lokanu 1 as soon as possible in order to provide the necessary protection for gun installations and to threaten the Japanese line of communication to Moten’s area. Expecting to reach their objectives in one day the two inland companies (led by Captains Colvert and Kindt) underestimated the terrain and the time required. The third company (Captain Gehring’s) moved along the coastal track on the morning of 18th July, but, when it became evident that the other companies would not be

in position by the end of the day, it halted half way between Lake Salus and the lagoon. By the next evening a Papuan platoon moved into position to attack a Japanese outpost south of Boisi. On the morning of the 20th the platoon killed four Japanese and then Gehring’s men destroyed the outpost. With the Papuans scouting ahead the American company advanced to Boisi meeting no further resistance.

Gehring’s advance was now harassed by Japanese guns and mortars from Roosevelt Ridge, 1,500 yards distant, and 12 men, including the company commander, were hit. American artillery began counter-battery work, while the company withdrew and dug in south of Boisi, where it was joined later that night by the two companies which had moved along the inland track. On 21st July the artillery supported the move of the remainder of the battalion into Tambu Bay, and that night, in the face of sporadic fire, more reinforcements, including two 25-pounders of the 2/6th Regiment, heavy machine-guns and anti-tank guns for beach defence, and Bofors anti-aircraft guns, arrived.

From information gathered by the Papuans Savige was convinced that the Japanese were lightly holding the eastern end of Roosevelt Ridge. As the map showed that the ridge rose to a greater height on the western flank, he considered that it would be wiser to go for this apparently undefended area and, after obtaining a footing, move east along the ridge and attack the Japanese from the high ground. Savige signalled Coane on 21st July about a track leading to this western flank, and informed him that it was essential to occupy the high ground to prevent the escape of the enemy from Mount Tambu along this route and to protect the American’s western flank. As a result a Papuan platoon was sent by Coane on 22nd July to set up an ambush in this western area.

On the same day at 7 a.m. Kindt’s and Gehring’s companies attacked the eastern end of Roosevelt Ridge. The attack which reached to within 50 yards of the crest of the ridge was unsuccessful and the two companies withdrew to the original perimeter near Boisi. Savige then signalled Herring asking for permission to use the II/162nd Battalion also. Herring replied that the remainder of the regiment would be sent forward as soon as possible. The III/162nd Battalion made further unsuccessful attempts to dislodge the Japanese from Roosevelt Ridge that day.

After these failures Savige on the 23rd sent a strong signal to Coane reminding him that the task allotted him on 15th July of securing a bridgehead at Tambu Bay entailed occupying Roosevelt Ridge and also the high ground to the west. The signal continued:

A frontal attack by you on ridge to north of bay has failed. No effort to outflank the enemy’s west flank appears to have been attempted. The enemy opposing your advance is not strong and is numerically weaker than forces available to you. In addition you have sufficient artillery to support your operations. It is considered that determined action by your forward commander to carry out your original plan which included an outflanking move along ridge to west would have succeeded.

Coane was then directed to send one company to secure the high ground to the west where he had previously sent only a detachment of Papuans.

He was also ordered to maintain contact with the Japanese on Roosevelt Ridge, to dig in and consolidate any gains, and to prevent his troops withdrawing to a close perimeter on the beach each night. Savige felt sure that a coordinated attack from the south and west must succeed.

As a result Coane sent a company to the high ground west of Tambu Bay with orders to verify the existence of Scout Ridge Track and, if found, to patrol it southwards towards Mount Tambu until meeting the enemy, and northwards to the junction of Scout and Roosevelt Ridges. All other companies were still in perimeters surrounding the flat Boisi area although Papuan sections, attached as scouts, were eager to lead the Americans into the hills. Coane signalled Savige on the 24th that he would attack next day down the ridge and from the flat ground North-east to Roosevelt Ridge. “This force will be on the way towards securing the ridge north of Tambu Bay before dark 25th July,” signalled Coane.

Artillery bombardments continued on both sides. Some of the Allied shelling was directed by Lieutenant Donald W. Schroeder of the American artillery. On 24th July Sergeant Makin9 and three Papuan soldiers led Schroeder to high ground west of Tambu Bay whence he could bring down fire on the enemy on Roosevelt Ridge. After the shelling the patrol reached the base of the ridge where Schroeder was wounded by a patrol of about 10 Japanese. Moving to Schroeder’s side Makin placed himself between the wounded man and the enemy. Emptying his sub-machine-gun into the Japanese he forced their withdrawal, dressed Schroeder’s wound, telephoned for a stretcher and succeeded in withdrawing with the stretcher party.

Australian artillery officers were also in forward positions ready to direct the fire of their guns. By the time that the first two 25-pounders from the 2/6th Field Regiment landed at Boisi on the night of 21st–22nd July Lieutenants Dawson10 and Lord11 had already left to be observation post officers for the 15th and 17th Brigades respectively. Major Thwaites was disturbed on 23rd July when he found that his two guns were within 1,000 yards of the Japanese positions and were outside the perimeter to which the Americans had withdrawn for the night. He also was a victim of the confusion of command which still existed on 27th July, and signalled his headquarters in Buna that he was receiving conflicting and impracticable orders from several Australian and American sources.

The reports from Savige’s liaison officer with Coane Force, Captain Sturrock, were not encouraging. As with the I/162nd Battalion in the early days at Nassau Bay, opposition caused the III/162nd to cluster in a close perimeter at night instead of holding the ground gained. This had been noticeable during the advance on 20th and 21st July. The attack on 22nd July was again followed by a withdrawal to the original perimeters

even though the attacking companies had gained much valuable ground. “Am most unpopular over trying to get information re future operations and sitreps,” wrote the liaison officer. Major Roosevelt resented suggestions and did not want Australian advice. “The only way I can get information is to remain within battalion headquarters area and listen in to “Ione conversations,” continued Sturrock’s report. His conclusion was that “the organisation at battalion headquarters stinks. ... If the show continues as it is now going I can’t see them getting very far.”

The Japanese in the Tambu Bay area when the Papuan and American soldiers entered it were mainly members of Major Kimura’s III/66th Battalion to which General Nakano of the 51st Division had given the task of driving the Americans from Nassau Bay. Instead, Major Oba’s III/102nd Battalion had been driven north from Nassau Bay and had passed through Kimura’s position north of Lake Salus, on its way to Kela Hill. Kimura had been unable to accomplish his task and by mid-July he was on the defensive. Nakano was now very anxious about his southern coastal flank and the threat of the advance of the Allies’ big guns capable of shelling Salamaua. On 21st July he sent south a reserve company which had marched hurriedly from Finschhafen and 250 men from the 115th Regiment, thus seriously depleting Salamaua of reserves.

On the central front the 17th Brigade continued to push north after the capture of Mubo. By 14th July Bennett Force from the 2/5th Battalion relieved the 2/3rd Independent Company in the Goodview Junction area while the remainder of the battalion was moving up the Buigap as far as the Bui Alang Creek.

Savige informed Moten and Hammer on 13th July that the Japanese in the Komiatum–Mount Tambu area must be destroyed before his plan to exploit the Mubo success could be carried out. Moten was therefore ordered to clear the Japanese from south of Goodview Junction, contain them there and attack Komiatum from the western flank. He was permitted to use Colonel Taylor’s American battalion to contain Goodview Junction so that Bennett Force could rejoin the 2/5th Battalion for the flank attack. Meanwhile Herring had written to Savige on 13th July suggesting that Moten might bypass Goodview Junction which now seemed of secondary importance to the vital Orodubi–Gwaibolom area which was really the key to Komiatum. He wrote:

At this distance I realise that it is hard to know exactly what is in your mind or how far troops are committed in any particular direction. I would however feel much happier about your future prospects if I knew you held the Orodubi–Gwaibolom area in strength as a base from which you can again control the Komiatum Track. ... With this track controlled in this way you bottle the enemy at Komiatum as you have done at Mubo.

Savige replied that he already held the general locality of Goodview Junction which was the highest point on the track north towards Komiatum and south towards Mubo. He recognised the importance of Gwaibolom and Orodubi, but his views, “based on a mass of information at my disposal and a personal knowledge of this type of country”, led him to believe that the best direction for an attack on Komiatum would be from

the west. “With any luck,” he wrote, “I can cut his line of communication from Lokanu–Komiatum. If so, Mubo will be repeated.”

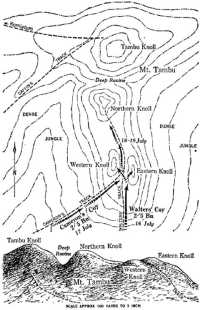

Moten’s instruction, issued before receipt of Savige’s signal, was to exploit northwards and destroy the enemy round Komiatum. The 2/5th Battalion, with a company of I/162nd, was ordered to clear the enemy from the area north of the Bui Alang Creek along the main Mubo–Komiatum track, secure Tambu Saddle and the line of communication to Base 4, and destroy the enemy in the Komiatum area.

When the 2/5th took up its position on the 15th, Captain Bennett’s company was 500 yards South-west of Goodview Junction astride Walpole’s Track with patrols to Stephens’ Track; Captain Morse’s was 500 yards south of the junction astride the Komiatum Track and on the high ground between Komiatum and Walpole’s Tracks, and Captain Cameron’s in reserve. Captain Walters’12 company moved North-east up a new very steep track known as Walters’ Track, intending to occupy Mount Tambu, and reached a point 500 yards from the top of a spur running south from the mountain.

Next afternoon at 5 p.m. Walters’ company (about 60 men) approached Mount Tambu from the south and attacked up a steep razor-backed spur heavily defended by enemy positions overlooking the rise. Lieutenant McCoy’s13 platoon attacked on the right but was pinned down. On the left flank Sergeant Tiller,14 out in front of his men, wiped out an enemy machine-gun crew. After hand-to-hand fighting in which 20 Japanese were killed, Tiller captured enemy positions on the eastern of the two southern knolls or humps of the approach ridge to Mount Tambu. The third platoon led by Lieutenant E. R.

Reeve then attacked and captured the western knoll. The Japanese remained on a northern and higher knoll, leaving about 100 yards of jungle-covered no-man’s land between the two forces. Walters’ attack finished at 6 p.m. when he consolidated the captured positions as well as he could before darkness. As the men had not carried digging tools it was fortunate that they had captured a Japanese position with pillboxes and weapon-pits for 100 men.

Realising their tactical error in allowing the Australians to gain this toehold on Mount Tambu the Japanese counter-attacked eight times during the night. They crawled to within 10 or 15 yards of Walters’ position before rushing the defences, firing and screaming. “Fighting was thick and furious during these counter-attacks and the small arms fire was the heaviest I’ve known,” said Walters’ report. His ammunition was used sparingly but even so the riflemen were down to five rounds each and the Bren guns to two magazines a gun by morning. The Japanese fired 120 mortar bombs into the company’s position during the night. Mortaring, shelling by a mountain gun, and a hail of fire from light and medium machine-guns failed to shake the defenders’ resolve. At 8.30 a.m. on the 17th Cameron’s company with a detachment of 3-inch mortars moved up to support Walters along a new and better track discovered by Cameron himself – Cameron’s Track. Walters’ ammunition and supplies were replenished and the two companies prepared to face enemy attacks down the North-south razor-back. Cameron dug in on a knoll 300 yards back along the track to give depth to the defences.

Meanwhile Captain Newman’s company of the I/162nd Battalion was at the junction of the Buigap and Bui Eo, and the remainder of the battalion farther back along the Buigap. A reconnaissance patrol from the mountain battery found suitable gun positions North-west of the junction of the Buigap and Bui Eo. With the assistance of 90 natives and 80 men from the 2/6th Battalion two guns were hauled over the precipitous track along the Buigap; by dusk on 17th July both guns were in position, and four guns of the American 218th Battalion were being hauled from the south arm of the Bitoi over Lababia Ridge to Green Hill.

The Japanese from Mount Tambu attacked Walters’ company again at noon on the 17th, but with a fresh supply of ammunition, particularly 3-inch mortar bombs, Walters held the enemy at bay. During the afternoon enemy movement to the north enabled the crack shots among the defenders to do some sniping: Sergeant McCormack15 killed eight Japanese and Private Kirwan16 four. At 6 p.m. about 200 Japanese attacked Reeve’s position, but, although outnumbered ten to one, the platoon repulsed the attack. After this attack had petered out little vegetation remained between the Japanese and Australians.

Supported by the mountain guns and 3-inch mortars Walters attacked North-west on 18th July to clean out a Japanese pocket and gained an

extra 80 yards of toehold among the lower Japanese positions. This advance was made possible largely by the exploits of Lance-Corporal Jackson,17 one of Sergeant Tiller’s section commanders. Using three grenades he destroyed an enemy machine-gun post and then wiped out the three occupants of a pill-box with his Tommy-gun. With this extra ground Walters strengthened his position but could not advance farther because of the difficulty of encircling the Japanese on the razor-back to the north. As both companies were at only half strength, Cameron placed Lieutenant Martin’s18 platoon under Walters’ control on the western flank. Water, ammunition and food were carried forward by the other two platoons in the afternoon. The battalion’s medical officer, Captain Busby,19 set up two large American tent flys for a forward post in the middle of Cameron’s position.

It was now apparent that Conroy was faced with a stalemate similar to that which confronted Guinn during his attacks on the Pimple two months earlier. It was also apparent that the Japanese were determined to eliminate the Australian hold on the southern fringe of their Mount Tambu fortress. If the Japanese attacked the entrenched defenders the pattern of Lababia and not the Pimple might be repeated.

The enemy at Tambu were temporarily repulsed (said the 51st Division’s Intelligence Summary on 18th July), but with the second attack we finally withdrew. Although the front-line company has counter-attacked, the enemy is not yet dislodged.

In the evening a severe earth tremor startled the troops. It rained heavily on the night 18th–19th July but this did not deter the Japanese from moving in darkness from Mount Tambu to the flanks of the two companies of the 2/5th. Despite the torrential downpour the guards of Cameron’s rear platoon heard noises and reported to their platoon commander, Lieutenant Miles. At about 4 a.m. on the 19th a signaller woke Cameron to report that the telephone line was dead. Just then the Japanese charged out of the darkness. A defending Bren gunner, with a lucky burst into the darkness, knocked out the raiders’ machine-gun which had been firing along the track into the centre of the Australian position. All enemy attempts to recapture their machine-gun resulted in their dead being piled up along the track. Confidence and steady defence by Miles’ men kept out the Japanese who withdrew just before first light leaving 21 dead, including one officer and two NCOs.

The Japanese from Mount Tambu viciously attacked Walters’ positions in the afternoon. In the company’s forward section post only Private Friend20 and a Bren gunner (Private Prigg21) were in occupation because

the remainder of the section was away bringing up supplies and ammunition. With fire from Tommy-gun and Bren, Friend and Prigg managed to hold the section post for 20 minutes against fierce attacks until the section returned. When the enemy attack was at its most critical stage and ammunition was short, Tiller advanced towards the enemy throwing grenades and inflicting such casualties that the early attacks were beaten off.

Sporadic attacks on the forward company continued during the day but none had the intensity of the pre-dawn attack, although the battalion diarist described them as culminating in a “terrific battle”. As usual the Japanese increased the din of battle with screaming and yelling, for example: “Come out and fight, you Aussie conscripts”, and “Come out and die for Tojo.” On several occasions the Japanese reached within 10 yards of the defenders’ pits. All available men from Moten’s headquarters and his two Australian battalions were used to carry ammunition and supplies forward day and night. In the end the determination and experience of a seasoned unit prevailed and the Japanese retired to Mount Tambu. Walters reported: “By 2.30 p.m. that day we knew we had him. Our men stood up in their trenches and sometimes out of them yelling back the Japs’ own war cry and often quaint ones of their own. One of them knew a smattering of Japanese and had a great time, shouting out such things as ‘Ten minutes smoko, lads’. It developed into absolute slaughter of the Jap and we literally belted him into the ground.” The Australians considered an estimate that the enemy had suffered 350 casualties to be conservative while the two exhausted but undaunted companies had lost 14 killed and 25 wounded.

At 5.30 p.m. on the 19th Walters’ company was relieved by Cameron’s and withdrawn to the junction of Walters’ and Cameron’s Tracks, while Newman’s Americans occupied the positions vacated by Cameron. The battalion’s second-in-command, Major N. L. Goble, now took command of this force on the southern slopes of Mount Tambu.

The 129 rounds fired by the mountain guns and the supporting mortar fire had been invaluable in breaking up the attacks. True to the traditions of artillery forward observation officers, Lieutenant Cochrane, the mountain battery’s FOO, had operated within 50 yards of the foremost Japanese positions.22

From 19th until 23rd July patrols probed the Japanese positions in the Mount Tambu and Goodview Junction areas. Bennett’s men on 20th July made contact with a strong Japanese position down Walpole’s Track. Morse’s company found Japanese positions in the Goodview area and dug in within 100 yards of them. As usual the Australians did all the patrolling, the Japanese being content to sit tight. Patrols to the flanks of Mount Tambu found strong defensive positions on the Japanese right and left flanks, and disclosed that the track connecting Goodview Junction and Mount Tambu was well used by the Japanese. Another track

– Caffin’s Tracks – was discovered leading to Mount Tambu from Bui Eo Creek. All indications were that the Japanese were extending and improving their defences. Savige informed Moten that artillery would be on the coast in a few days’ time, and no advance was to be made without it.

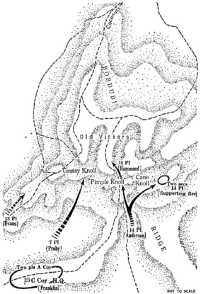

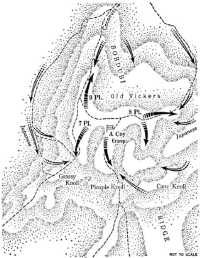

On 13th July Savige ordered the 15th Brigade to secure Bobdubi Ridge from Namling in the south to Old Vickers Position in the north. This would prevent the Japanese escape from the Komiatum area by securing the Komiatum–Salamaua–Bobdubi track junctions, and support Moten’s flank attack on Komiatum. Hammer next day issued orders which, he hoped, would enable him to regain the initiative. The 2/3rd Independent Company on 15th July would attack Ambush Knoll where the Japanese had been digging in for the past two days, and would then exploit to Namling Ridge. On the same day the 58th/59th Battalion would seize the northern track junctions where the Komiatum and Bench Cut Tracks met the Salamaua–Bobdubi track. These attacks would be followed on 16th July by a concerted attack by the Independent Company and a company from the 58th/59th on Graveyard and Orodubi.

After its relief at Goodview Junction, the Independent Company was again short of rations and was forced to borrow from the 2/5th. Most of the company’s native carriers stationed at Vial’s OP were sick and hungry. When the company moved to Wells Junction on 14th July in preparation for the attack on Ambush Knoll rations were scraped together from Base 4 and Vial’s OP and arrangements made for future rations to come up Uliap Creek from Nunn’s Post. Rations were barely sufficient for the attack on Ambush Knoll.

Warfe planned that one platoon (Captain Meares) would attack from the south while another (Captain Winterflood) went round the east flank and attacked from the direction of Orodubi. On 15th July Meares’ platoon attacked Ambush Knoll at 1.45 p.m. after half an hour’s supporting fire from two Vickers guns and a 3-inch mortar. The entrenched position was strongly held by the Japanese who flung Australian grenades at the attackers. In the centre six men under Corporal McEvoy23 were the spearhead. Although under heavy fire McEvoy leaped over a bamboo barricade across the ridge. Only one of his men (Private Collins24) could follow him across the barricade as the others were wounded by a grenade. McEvoy had expected that the bombardment would have killed all the Japanese on the knoll. He wrote afterwards:

When I got over that barricade with half my shirt ripped off my back by a machine-gun burst and four bullet grazes across my ribs, I realised it was no place for Mrs McEvoy’s little boy and the first thought was to let the Nips keep the place, but then I noticed I had one man with me and he had the light of battle in his eye and was shouting above the din, “Come on Mac, let’s go through the b – s.”

‘Named after Sergeant M. L. Caffin, 2/5th Battalion (of Canterbury, Vic), who discovered it.

The dash of McEvoy and Collins enabled Meares’ troops to occupy these positions 50 feet from the main barricaded pill-boxes. In this advance Private Wellings,25 firing his Bren from the hip, destroyed one Japanese machine-gun. The adjutant, Lieutenant Harrison,26 was killed and 9 others wounded. Meares was then reinforced by Lieutenant Egan’s section, bringing his total assaulting force including casualties to 50, but by nightfall the Japanese, estimated at about 30, still held on.

While Meares was attacking Ambush Knoll, Winterflood led his platoon, reduced by casualties and sickness to 30, in an attempt to cut the enemy track from Orodubi to Ambush Knoll. He did this, and, after driving back an enemy party from Orodubi, made a spirited attack with hand grenades on Ambush Knoll, supported by covering fire.

The determined attacks by the two platoons made the position too unhealthy for the Japanese. At first light on 16th July patrols from the Australian platoons met on Ambush Knoll which the enemy (members of the II/66th Battalion) had vacated during the night. The Japanese defensive position which had two log pill-boxes and a perimeter with a circumference trench 100 yards long had been occupied by double the number previously estimated. In their haste to depart, the Japanese left 10 corpses on the knoll.

The 58th/59th Battalion meanwhile was preparing to carry out Colonel Starr’s orders to “maintain offensive action” against the Japanese on Bobdubi Ridge north from Namling and to gain control of the Komiatum Track. One company (Lieutenant Griff’s) was ordered to clear the Bench Cut and advance north down to the Salamaua–Bobdubi track; two others were to patrol Bobdubi Ridge; and the fourth (Captain Jackson’s27) was to hold the Gwaibolom–Erskine Creek area against any attack from the south.

Unfortunately, the battalion’s plans were upset when the Japanese drove one of Jackson’s platoons from Erskine Creek on 14th July. Griff’s company while moving to the Bench Cut met other Japanese who stopped any further advance and called down the fire of a mountain gun on the Australians. Griff was then ordered to recapture Erskine Creek in cooperation with Jackson. The two companies failed to meet, Erskine Creek was not recaptured, and the 58th/59th Battalion was not in a position to carry out its plan.

On the 16th Griff tried to find positions from which to attack the enemy flank in the Erskine Creek area. Concluding that the only means of progress was along the Bench Cut, he found that this track had been heavily reinforced and Japanese were encountered in four places along 600 yards of the track. Hammer then revised the plan: Jackson was ordered to capture Graveyard on 17th July with the assistance of Warfe

from the south, Griff to attack the Japanese positions on the Bench Cut, and the other two companies to be ready to capture Old Vickers and the Coconuts in readiness to push on to the Komiatum Track. After assisting in the capture of Graveyard, Warfe would capture Orodubi. The 58th/ 59th had thus been given a huge area to capture – from Coconuts to Graveyard. It was too much for even the best trained troops.

The Independent Company fulfilled its small part in the plan. Lieutenant Barry with 10 men attacked Graveyard at 10.50 a.m. on the 17th and by 5 p.m. this small force, reinforced by six men, captured its objective, killed at least five Japanese and repulsed two counter-attacks. Barry was unable, however, to guarantee that he could hold his position against larger numbers of Japanese which he might have to face. Already on this day 119 Japanese had been observed moving north from Komiatum, probably to reinforce the Orodubi area, and no troops were available to reinforce Barry.

Jackson’s company of the 58th/59th meanwhile encountered enemy positions 500 yards south of Gwaibolom on the morning of 17th July soon after it set out for Graveyard. Attacks on these on 17th and 18th July were repulsed. Worse still, it became apparent that the Japanese were gaining the initiative in this area, for Jackson found more Japanese in positions 400 yards North-east of Gwaibolom. He withdrew to Gwaibolom in face of the crowding enemy. Griff’s patrols farther north established the fact that the Japanese were holding Erskine Creek area in strength. With no reinforcement available from south or north Barry was forced to withdraw from Graveyard to Namling Ridge on the morning of the 18th by superior numbers of Japanese.

The Japanese troops seen moving south on 17th July towards the area precariously held by Barry were probably members of Jinno’s I/80th Battalion which was apparently in the Komiatum area with the I/66th Battalion and the remnants of II/66th Battalion. Since its arrival at the beginning of the month the I/80th Battalion had been in action at Bobdubi. On 17th July Jinno’s order stated: “The battalion will assemble in strength at the present area and will attack the enemy in the Wells area.”

North of the Francisco, a patrol from the 58th/59th investigated a report that Japanese had been heard crossing Buiris Creek on the night of the 17th–18th July. The patrol found positions occupied by 50 to 60 Japanese one hour’s journey from the junction of the Francisco River and Buiris Creek. This report disturbed Hammer who was well aware of the weakness on his northern flank. The tactical position of his brigade on the night of 18th July was not satisfactory. Because of the failure of his plan, he decided to concentrate on capturing Graveyard and freeing Jackson’s company for use as a reserve in the area north of the Francisco. To coordinate the attack on Graveyard and to ensure that the Namling–Dierke’s track was sufficiently held, Hammer sent Travers to Namling.

At 8.15 p.m. on 19th July in bright moonlight about 60 Japanese overran the Independent Company’s listening post south of Ambush Knoll on the ridge track to Wells Junction, and attacked the two sections led

by Lieutenants Egan and Garland28 on Ambush Knoll. At this stage Warfe’s headquarters was at Namling where Winterflood’s weary platoon returned in the afternoon of 19th July, Meares’ platoon was occupying the area south from Ambush Knoll to Wells Junction, and Lewin’s platoon was on Namling Ridge. Realising the threat to the divisional line if the enemy succeeded in recapturing Ambush Knoll, Warfe sent Winterflood with two of his sections to reinforce Ambush Knoll and take command there. The first Japanese attack on Ambush Knoll was repulsed; the Japanese attacked again at 9.30 p.m., five minutes before Warfe dispatched Winterflood’s platoon. In the defence very effective use was again made of the Independent Company’s Vickers guns. They were sited in the forward trenches – one directed along the ridge towards Wells Junction and one along the ridge towards Orodubi. Their targets were at hardly more than 30 yards’ range.

Hammer now well realised that his forces were not sufficient to attack the enemy in the large area for which his brigade (only a battalion and an Independent Company) was responsible. The Japanese now had more troops available on the spot as their line of communication was not so long as it had been before the capture of Mubo. They were holding the high ground near Gwaibolom and appeared to be trying to seize the high ground in the Wells OP area. Captured documents led Hammer to believe that the Japanese line of defence was Mount Tambu–Goodview-Buirali Creek–Orodubi-Old Vickers. With his plans again frustrated Hammer informed his brigade on 19th July that its task was generally to continue offensive operations in order to maintain control of Bobdubi Ridge and gain control of the Komiatum Track.

Winterflood’s platoon joined Egan on Ambush Knoll at 6.30 a.m. on 20th July. Soon after its arrival the Japanese gained the main ridge track, thus effectively sealing off supplies by the main route. Attacks by the enemy continued almost without let-up on this day, when 12 separate thrusts were repulsed by the tenacious defenders. Warfe wrote later that “the Japs attacked bravely and in large numbers and the fight for Ambush Knoll developed into a classic defence”. The machine-gun crews put their guns on loose mountings and “hosed” the approaches whenever movement was seen. In Warfe’s opinion “these guns undoubtedly saved the situation by their characteristic of sustained fire”. From Namling Ridge Lieutenant Lewin could see the Japanese moving from Orodubi to Sugarcane Ridge which was their base and control area for the attack on Ambush Knoll. Warfe therefore placed a Vickers gun with Lewin at the junction of Nam-ling Ridge and the main track. From here Lewin fired on enemy movement at a range of 700 yards across the deep re-entrant to Sugarcane Ridge.

Hammer had been hoping to reduce his front by encouraging the advance of the 17th Brigade along the Komiatum Track. “I felt that the greater weight of enemy was directed at Bobdubi and not towards Tambu,” he wrote later, “as the Japs must have felt our pressure from the Bobdubi

area although we were not making good headway.” From a long distance away it seemed to Hammer that the 17th Brigade was slow in reacting to the Japanese withdrawal particularly as he considered that the enemy had become defensive in the Tambu area “while they became offensive on the Bobdubi front which threatened to eat into their middle”. He also thought that if the enemy established themselves in the Wells Junction area the advance of the 17th Brigade would be jeopardised. In Hammer’s opinion he was trying to hold ground “vital to the whole operation”.

He therefore signalled Savige suggesting that the 17th Brigade should take over responsibility for the area north to Namling. Savige agreed and explained the critical situation by phone to Moten, proposing as a matter of urgency that the 2/6th Battalion be sent immediately to the area south of Namling Moten complied wholeheartedly even though it might mean upsetting his own plan. There was nothing except lack of supplies to stop a rapid move forward by the 2/6th Battalion, and Lieutenant Price’s company set out from the Mubo area to establish a base at Wells OP and patrol east and north down Buirali Creek to prevent Japanese movement south. Savige signalled to Herring on 20th July that he had explored and put into action “every conceivable abnormal method” to supply the battalion with rations and ammunition and even then then had not been enough. “My ability to meet present situation and defeat Japs depends entirely on large and sustained droppings,” he signalled.

At 3 a.m. and again an hour later on 21st July enemy night attacks on Winterflood’s men on Ambush Knoll were repulsed. Again the Vickers guns played a vital part with Lewin’s gun joining in by firing along a fixed line from daylight observation. Enemy attacks waned on the morning of the 21st although a heavy machine-gun firing from Sugarcane Ridge on to Namling caused a scatter at Warfe’s headquarters just after breakfast.

The progress of the fight was followed anxiously at company headquarters, whence carrying parties worked constantly taking up supplies to Ambush Knoll. Every spare man, including some natives who would not normally have been so far forward, were pressed into service. As the attack intensified all regular approaches were cut, but for some unexplained reason the enemy left open one means of access up a western spur from Uliap Creek and the supplies got through. Of great value to the morale of the defenders were the dixies of hot tea and stew which were hauled up this precipitous route and carried from one weapon-pit to another during lulls in the fighting. Both sides used up ammunition at a fast rate. The enemy were supported sporadically by a mountain gun from Komiatum Ridge, by a heavy mortar from Orodubi, and by light mortars from Sugarcane Ridge. At 1 p.m. another fierce Japanese attack was beaten off by the stubborn defenders. They suffered a severe loss when one of their outstanding leaders, Lieutenant Egan, was killed by a mortar bomb explosion. Although very tired, Winterflood’s men were in high spirits and answered the enemy’s English phrases with other unprintable English retorts.

When Price’s company, leading the move of the 2/6th Battalion, arrived at Wells Junction in the early afternoon of 21st July Major Travers met them. Price’s written orders were to establish a base but not to fight; he did not know that the 17th Brigade was to take over the area south of Namling next day. Travers asked him to attack the Japanese on Ambush Knoll and relieve the pressure on Winterflood as soon as possible. “I explained the whole position to Price,” wrote Travers later, “and Price had sense enough to see it was easy enough to help Warfe and guts enough to go against written orders.” Price wrote later: “On arrival Major Travers told me that my instructions were two days old. As I had not been in touch with the battalion I had no reason to disbelieve him when he assured me that Brigadier Hammer had later orders from 17th Brigade for my company to attack Ambush Knoll.” Although worried about attacking without being able to make an adequate reconnaissance Price attacked down the ridge from Wells Junction to Ambush Knoll at 2 p.m. and came in behind the enemy. He met heavy opposition, lost two killed and several wounded, and had to be content with digging in on the slopes of Ambush Knoll close to the enemy.

In his diary for the 21st Travers noted: “At 1630 hours I got an order from 17th Brigade to say that the attack would not be launched without reference to 17th Brigade or 2/6th Battalion headquarters. I spoke to Tack [Hammer] about it but he ... said he agreed with my action. Anyway I am not especially worried about it except for a breach of etiquette. ... Had this company not attacked the Ambush Knoll would have been lost. I have no doubt at all on this.”

Hammer in a letter to Savige expressed his pleasure at “a bit of real stoush going on now”. He explained that Ambush Knoll was higher than Namling, Namling Ridge and Orodubi. “That’s why the Jap wants it.” Referring to Gwaibolom and Old Vickers Position he wrote: “The situation is much the same with the Jap firmly planted on the Bench Cut Track and until they can be shifted we have no hope of getting on the Komiatum Track. ... Strengths are getting low, 58th/59th Battalion about 460, 2/3rd Independent Company about 180.”

With Winterflood holding stubbornly and Price maintaining pressure from the south the Japanese finally had had enough, and at 6 a.m. on 23rd July Warfe himself guided Lieutenant Maloney’s29 patrol from the 2/6th Battalion via the secret route to Ambush Knoll where they joined Winterflood and reported to the thankful defenders that there were no Japanese in between, although some were still on Sugarcane Ridge. The vacated position from which the Japanese had attacked consisted of three pill-boxes with tunnelled trenches and weapon-pits, sufficient for 70 men. By 1.30 p.m. the 2/6th Battalion relieved Warfe’s troops of their responsibilities south of Namling–Orodubi and the weary Independent Company moved to Namling. During three days and four nights Winterflood’s men had been subjected to heavy mortar and machine-gun fire from Sugarcane

21st July

Ridge. Twenty separate assaults had been made using three different lines of approach. The chief thrust on all occasions came from the South-east with lighter attacks from Sugarcane Ridge and the ridge leading south towards Wells Junction. During the six heaviest attacks, all three approaches were used. The Japanese several times reached within a few yards of the Australian positions but on each occasion they were driven back. This successful defence of Ambush Knoll had accounted for 67 Japanese against 3 Australians killed and 7 wounded.

Savige breathed a sigh of relief when the Japanese finally withdrew. He had been apprehensive of an enemy breakthrough along Dierke’s Track which might have prejudiced his entire operations by enabling the Japanese to establish themselves between his two brigades.

The 2/7th Battalion was now about to re-enter the battle area after a two months’ spell in the Wau–Bulolo valley. On 22nd July Savige had received a message from Herring that recent information suggested the possible reinforcement of the enemy in the Salamaua area. Herring therefore authorised Savige to move the 2/7th from the Bulolo Valley immediately and Savige decided that the battalion would be attached not to its parent brigade but to the 15th to stiffen his force in the northern area.

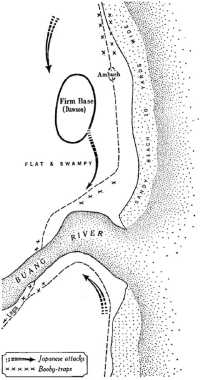

Along the Markham there were no clashes at this time. However, in the South-eastern portion of Lieut-Colonel Smith’s huge domain of jungle, mountain, river and swamp Lieutenant Dawson’s patrol of the 24th

Battalion near the mouth of the Buang was preparing for trouble. On 15th July a native saw the patrol’s sentry and escaped towards Labu. Next day the Australians found footprints leading to the old ambush position, and on the night 18th–19th July heard a great deal of barge movement along the coast. Of more intimate concern, however, was the explosion of the patrol’s northern booby-trap along an old native track 100 yards north of the base. Next morning a small patrol found a large pool of blood, four field dressings with the anchor sign of the Japanese marines on them, and the marks of a four-man patrol. After a day of uneasy calm a booby-trap in the same place near the mouth of the Buang exploded at 8.30 a.m. on 21st July. Investigations showed signs of casualties and tracks of a large party of Japanese on the beach.

At 10.30 a.m. a six-man patrol acting as a protective force for Sergeant Lane,30 who was re-laying the exploded booby-traps, found at least 12 Japanese field dressing covers, and pools of blood. While examining these signs the patrol heard Japanese talking and next moment was attacked by about 20 of them. Private Rowley31 swiftly killed two with his Owen and Private Kleinitz32 one, before the patrol was forced to withdraw to the ambush position while the Japanese moved south along the beach and also began an outflanking movement through the bush to the left of the ambush.

Dawson’s position in thick jungle was not sited to withstand strong attacks from rear and flank. Heavy machine-gun fire and shells from a mountain gun soon forced him to withdraw to his firm base. Enemy pressure along the track continued, and when a party of more than 20 Japanese were seen crossing the Buang from south of the ambush position Dawson retired along the Lega Track without being able to carry out his stores, ammunition and rations. The Australians set another ambush one hour farther west but as very little ammunition and rations were left Dawson withdrew to Lega by 5.30 p.m., thus losing contact.

Kleinitz, who had been missing since the first action, arrived at Lega an hour later and reported that the Japanese had swarmed into the ambush position from the beach and through the bush. He shot one more Japanese and heard and saw what he estimated was about 200 in the area. Being one against 200, Kleinitz returned to the firm base where he found no Australians. Private Murphy,33 who was the last man to leave the ambush position before it was overwhelmed at 11.40 a.m., fired a full Owen magazine into a group of Japanese moving along the beach. Dawson estimated that 14 Japanese were killed during the action. The last missing man from the Buang action, Private Hillbrick, arrived at Lega on 22nd

July and reported hearing two of the booby-traps on the southern end of the ambush position exploding before he left.

A reconnaissance patrol along the Buang on 22nd July did not reach far enough to establish whether the Japanese were still at the mouth of the river. Savige then ordered Smith to use Dawson’s platoon as a “commando” force which would operate from a base east of Lega and harass and delay the Japanese force.

General Nakano’s anxiety about an Australian thrust down the Buang River Valley or a landing at its mouth caused him to tie up a large part of his 102nd Regiment there, plus detachments of the 115th. Patrols between 17th and 20th July failed to meet the Australian enemy although one patrol which left at 8 p.m. on 18th July ran into Dawson’s booby-traps. By 20th July about 100 men from the 102nd Regiment and the marines were in occupation of the mouth of the Buang. Nakano’s Intelligence report for 21st July stated that in the clash between the “naval party” and the Australians one Japanese officer was killed and 7 soldiers wounded.

General Adachi and his staff officer in charge of operations, Lieut-Colonel Tanaka, were also concerned about the intentions of the Australian force in the Buang Valley. After the war they said: “From the beginning of July onward an Australian force, which had been stationed at Wampit, pushed down in the direction of the Buang. It was considered at the time that the object of this manoeuvre was to secure Buang and facilitate a landing by Allied troops from the sea. In order to prevent this, about 150 men of the 102nd Infantry Regiment attacked the Australian troops who had reached Buang from Wampit and occupied the position.

Savige on 23rd July appointed the American Colonel Jackson to command all American and Australian artillery units, and Major Scarlett34 was allotted to Jackson as brigade major. The 205th American Field Artillery Battalion (105-mm guns) and the 218th Field Artillery Battalion (75-mm guns) less one battery were allotted to support Coane Force; one battery of the 218th Battalion and one section of the 1st Australian Mountain Battery to Moten’s brigade; the 11th Battery of the 2/6th Australian Field Regiment to Hammer’s brigade. Brigade and force commanders were ordered to deal directly with commanders of artillery units allotted to their brigades when support from those units only was required. When larger concentrations were required requests would be made to Jackson who would coordinate all requests.

On the right flank of the battle area success was still denied the Americans. Colonel MacKechnie had been relieved of the command of MacKechnie Force on 22nd July, and at Tambu Bay Lieut-Colonel Charles A. Fertig was now Brigadier-General Coane’s infantry commander. The Americans were fortunate to have Captain Hitchcock’s Papuan company to help them pinpoint Japanese positions and thus save them from trusting too much to the unreliable Komiatum map (1:25,000). Because of their natural bushcraft, the native soldiers were better fitted than those of most units to iron out by reconnaissance the numerous discrepancies between map and ground, and to lead the American companies to their

correct positions. On 23rd July two Papuan soldiers approaching from the east along a track made the first contact between Coane Force and the 17th Brigade when they met an American platoon below Mount Tambu.

Savige signalled Coane on 26th July that as the II/162nd Battalion, commanded by Major Arthur L. Lowe, was arriving at Tambu Bay Coane should get his troops moving to secure the line from Lokanu 1 to Scout Hill. This battalion, which was now to receive its battle initiation, assembled at Tambu Bay between 21st and 29th July, and was given the task of capturing Roosevelt Ridge. Roosevelt’s battalion at the end of July was in the Boisi area with two companies on the slopes of Scout Ridge west of Tambu Bay.

On 27th July Captain Coughlin’s company from the new battalion attacked Roosevelt Ridge from the south, inflicted casualties on the Japanese and gained a firm hold on a small ridge slightly below the crest. The American troops showed their appreciation of this aggressive leadership by tenaciously clinging to the first substantial gain made by Coane Force since its arrival at Tambu Bay. Aided by Captain Ratliff’s company from the beach Coughlin’s company again attacked Roosevelt Ridge on 28th July and advanced a little farther. The two companies were counterattacked several times and were subjected to sniping and mortar fire, but held their ground. Two days later they tried unsuccessfully to improve their positions by attacking from the west. The Japanese were too well dug in along the steep narrow crest of the ridge; their defences were well camouflaged, mutually supporting, and often connected by underground tunnels. The reverse slope of the ridge was ‘similarly organised and, during the Allied artillery and mortar bombardments, the Japanese took shelter in their tunnels, and after the fire lifted, again manned their defences, often as the result of a bugle call and usually as the Americans began to attack. The Americans were learning that it was futile to batter well-prepared positions and best to encircle them.

The III/162nd Battalion was now concentrating on cutting the enemy supply route along Scout Ridge to the west of Tambu Bay. On 27th July Captain Colvert’s company destroyed a Japanese position south of the junction of Scout and Roosevelt Ridges, and next day made a substantial advance to a position 500 yards south of the junction where they withstood several attacks from the north. Meanwhile a patrol from Captain Kindt’s company, aided by a Papuan platoon, moved south along Scout Ridge towards Mount Tambu and encountered an enemy patrol moving north towards Scout Hill. The Americans dispersed the patrol, but were then forced back by a larger enemy force.

So the skirmishing and patrolling continued in the last days of July and the first days of August. There was no real progress. In a signal to Savige on 28th July Coane had said that he was upset that the calibres of the guns had been divulged to the enemy by the shelling of Salamaua before he could provide anti-aircraft support for them.35 “Both MacKechnie

and I assumed that it would take a full regiment plus two batteries of artillery to carry out our mission assigned,” he stated; “events have proved that estimate to be conservative. We must have more troops if we are to complete our mission.” Coane then requested an extra battalion and spoke of the threat to Savige’s flank and line of communication “if we are overcome” particularly as “we are extended for miles with no reserves whatever”. He concluded his signal with a statement which made Savige angry in view of all the trouble and time spent on this vexatious problem. “I wish to respectfully point out also that I have been placed in command of all American troops in this area by General Fuller including the Taylor battalion. This includes all American artillery as well as other troops.”

Upon receipt of this signal Savige, who had already censured Coane that day for giving instructions to Colonel Jackson, sent a brief reply saying he would arrive at Nassau Bay by “Cub” on 30th July and wished to be taken to American headquarters to discuss the points raised in Coane’s signal. Unable to secure a plane from Australian sources Savige asked Coane to send one. Released from his unpleasant duties at Tambu Bay Captain Sturrock guided the pilot of a Piper Cub sent to pick up Savige. Unfortunately the Cub crashed but Sturrock and the pilot escaped serious injury. Knowing that Coane had a second Cub, Savige asked him to send it across. This Cub landed at Bulolo and took Savige on 31st July through very bad weather to Nassau Bay. Four hours after landing he arrived at Coane’s headquarters by barge.

Although discussions between the two men were conducted in a friendly manner, Savige was shocked at what he considered was lack of control and discipline in the force. Savige showed Coane copies of Herring’s order of 23rd July and a directive from Fuller based on Herring’s order. Coane had not seen these orders and was in the dark about his role beyond that of placing the guns at Tambu Bay. Savige emphasised that all Australian and American units including artillery were under the command of the 3rd Australian Division and that Jackson, not Coane, was responsible to him for control of the artillery. Regarding Coane’s fear that the calibre of the guns had been disclosed Savige pointed out that the Japanese already knew of the existence of 75-mm and 105-mm guns in the area and were very worried about the shelling of Salamaua, which would be continued.

Finally Savige told Coane that he must push on immediately and capture Roosevelt Ridge and the high ground to the west in order to protect the guns and the base at Tambu Bay. When Coane protested that he must have the whole of his two battalions forward, Savige pointed out that it was neither necessary nor possible to hold a continuous line. He urged that the American troops must hang on to ground gained and dig in.

A signal from Coane to Savige and Fuller on 4th August was full of foreboding as to the fate of the Tambu Bay troops. Coane stated that his total infantry combat strength was 708, and was being lessened by the daily evacuation of about 50 sick and wounded. In four or five days his

strength would be so depleted as to make it impossible to hold the Tambu Bay area. He considered that the Japanese must attack in order to silence the guns, and that Allied reinforcements must arrive at once if he was to hold Tambu Bay and not lose the guns. Savige’s reply on 5th August, drafted by Wilton, said:

On all sections of divisional front units are depleted and in many cases are confronted with much greater difficulties and have been fighting continuously for a longer period. Your strength in men and weapons in proportion to your task is much greater than other sectors. Reports from your forward troops indicate that their morale is very high and their positions are secure. ... GOC does not agree that the situation at Tambu Bay is as desperate as you indicate.36

In the central area, meanwhile, Moten was preparing for another attack on Mount Tambu. On 22nd July 20 aircraft attacked enemy positions on Komiatum Ridge completely baring parts of it. That day Moten signalled to Savige an outline of his plan to capture Mount Tambu on 24th July with three companies of the 2/5th. Two other companies would attack limited objectives at Goodview Junction at the same time.

Colonel Conroy’s plan to capture Mount Tambu was issued on 23rd July and called for an attack next morning by two companies – Captain Cameron’s left of the main track and Captain Walters’ from the west along Caffin’s Track. The anti-tank platoon would establish a position astride the Mount Tambu-Goodview Junction track from the west.

Covered by Corporal Smith,37 Cameron crept forward before dawn on the 24th to within 15 yards of Japanese pill-boxes on the left of the track. Here he counted seven pill-boxes in two lines of defence on both sides of the track. Steep slopes on both sides gave little hope of a reasonable approach by more than one platoon at a time, and sharpened bamboo pickets on the left flank led Cameron to believe that an attack was expected there where it could be enfiladed from the west.38 From his reconnaissance and with the little time available to him Cameron had no option but to order a frontal attack with platoons in echelon, although he thought that a flanking movement wide to the right with two companies would have cleared Mount Tambu.

For 15 minutes before the attack Australian and American artillery fired on Mount Tambu. The two Australian mountain guns fired 90 rounds per gun while the four 75-mm guns of the American battery on Green Hill fired 60 per gun. The mortars also helped. Cameron attacked at 11.30 a.m. with Sergeant Williams’39 platoon on the right and Lieutenant

Leonard’s40 on the left. His intention was that they should drive a wedge into the two lines of pill-boxes and exploit to each flank, when Lieutenant Martin’s platoon would come through to clear the top. Cameron had 59 men against an estimated 400 entrenched on Mount Tambu. The assault was supported by the battalion’s Vickers guns from lower Tambu.

The Japanese let the two platoons reach almost the line of the forward pill-boxes before a storm of fire swept the advancing Victorians. Among the casualties on the right was Cameron who was moving with Williams’ platoon. He was wounded and, as the platoon hesitated under the onslaught, he yelled, “Forward and get stuck into them.” Williams, followed by Corporal Carey,41 then led the depleted platoon forward, and, with great dash, soon swept through the outer ring of Japanese pill-boxes.

On the left Leonard’s men captured two pill-boxes before the heavy enfilade fire from the left pinned them down. Cameron’s wound prevented him from carrying on and he handed over the attack to Martin who placed Corporal J. Smith in charge of his own platoon and sent him forward to clear the left of Williams’ successful advance. “Follow me,” called Smith, and with bayonets fixed the small band headed up Mount Tambu. With three men behind him Smith gained the crest of Mount Tambu beyond a third line of pill-boxes, but lack of reserves and severe casualties (16 including 3 killed), caused Martin to order a withdrawal. The Japanese hurled grenades at Smith’s gallant band in an attempt to stop their furious charge. Smith had literally to be dragged back semi-conscious but still full of fight. There were some 40 wounds in his body and he died later. During the assault Corporal Allen42 carried out the wounded and dressed their wounds.

Meanwhile, on the left flank Walters’ company had tried to cut the Mount Tambu–Komiatum track 600 yards west of Mount Tambu. While forming up off Caffin’s Track the Australians saw 115 Japanese moving east towards the Mount Tambu perimeter. This meant a substantial increase in the fortress to be attacked, but Walters was not in a suitable position to attack them on the track. No sooner had the company crossed the track than it came under heavy fire from an unsuspected enemy position on a precipitous razor-back 300-500 yards west of Mount Tambu. During the bombardment of Mount Tambu the Japanese had come forward from their positions and were thus able to bring down this fire on the discomfited company. The steepness of the track and the fire from the pillboxes ahead and the ridge to the west gave Walters no choice but to withdraw about 500 yards South-east to Caffin’s Track.

During these attacks and in order to create a diversion a platoon from Captain Morse’s company climbed through very difficult country and set an ambush on the Komiatum Track high up on Goodview Spur, where they waylaid a party of Japanese, killing three before being compelled to withdraw by a larger enemy force.

The inability of the 2/5th to capture Mount Tambu emphasised again the danger of attacking frontally high features on which the Japanese were firmly entrenched, without allowing time for very thorough reconnaissance and detailed planning. Had the attacking company commanders been given this breathing space, they might have found a way to encircle the enemy, they would certainly have gained a more accurate appreciation of the enemy’s strength and dispositions, and they might have been given a more adequate reserve. The pity was that, even so, Corporal Smith and his gallant band did reach the crest of Mount Tambu, only to be forced back again.

In this period the 2/7th Battalion had been marching forward. Savige had not exactly made up his mind where to use them and on 22nd July had signalled Herring that the enemy’s determined thrust at the Buang ambush position and intensified patrolling in the Buiris Creek area indicated large reinforcements from Lae. “Consider most disconcerting enemy blow my left flank,” he said, and added that he planned to move half the 2/7th to Hote–Missim. Believing that the principle of concentration of force was being departed from, Herring signalled that the dispersal of the 2/7th Battalion in the Hote area would involve keeping a fresh and well-trained battalion out of the “vital battle now impending Tambu Bay–Tambu Ridge”. He considered that enemy action on the left was purely defensive and involved spreading his forces “which is most desirable from your point of view”. He added: “Most desirable that you should not conform to what I believe is merely defensive action on his part but should concentrate your forces in the vital area. ... Most desirable 2/7th Battalion should revert to its brigade earliest.” Herring made it evident that Salamaua should continue to attract enemy troops from Lae, and that Savige should develop a sea line of communication to ease the general supply burden.

Savige replied on the 24th that his plan remained unaltered and that the “battle of Mount Tambu commenced this morning”. He added that his “concentration of greatest force and fire power within vital area complete and adequate”; and that the 2/7th Battalion, which could not arrive in time to participate in the battle, would move as previously planned to be a reserve to the 15th Brigade. “Movement of enemy from Hote over the mountains never contemplated by me,” he said. “Such luck not to be expected. I have defeated the enemy. I have inflicted heavy casualties on him. I have handled time and space better. I anticipate success equal if not greater than Mubo. I have the initiative and will retain it.”

After receiving Savige’s situation report in which the failure at Mount Tambu was noted, Herring sent a strong signal about the “failure your planned attack to capture Mount Tambu”, and urged “most resolute action required”. Savige replied on the same day that “yesterday’s operations were of a limited nature, a necessary preliminary to subsequent operations which include action by Conroy and Taylor in Mount Tambu–Goodview area, by Wood towards Sugarcane Ridge, with Coane and Hammer exerting pressure on the flanks”.

Herring was puzzled and worried at the apparent lack of frankness in these signals and at his difficulty in discovering exactly what was happening in the battle area. He was not to know that Savige’s signal about the beginning of the battle for Mount Tambu should not have been taken too literally. He could assume only that the battle had begun on 24th July, particularly when he read this signal in conjunction with an air force signal that an attack was to be made on Komiatum after an air strike which had been requested for 24th July. When he learned that either the attack had failed or the battle had not in fact begun Herring sent forward his chief staff officer, Brigadier Sutherland,43 who arrived at Bulolo on 26th July.

It seemed to Savige and his staff, however, that New Guinea Force did not fully understand the nature of his operations or the difficulties encountered in terrain, weather, supplies, the enemy; and that they lacked confidence in his conduct of the campaign. The air force signal had been sent without reference to divisional headquarters.

When Sutherland arrived at Bulolo he expressed NGF’s concern that attacks on Komiatum and Mount Tambu had failed. Savige asked Wilton and Griffin whether any battle had been fought and they replied in the negative. Savige then repeated that the attack on Mount Tambu had the limited objectives of gaining information and, if possible, ground, while no attack had been made on Komiatum. The discussion then centred on Sutherland’s doubts whether there was sufficient force available to capture Mount Tambu, and his desire to know exactly when Komiatum and Mount Tambu would be captured. Savige said that he had enough troops but that he could give no guarantee when the two objectives would be taken.

After detailed discussions about supply Sutherland passed on Herring’s message urging that divisional headquarters should move forward from Bulolo in order to make the eventual supplying of the whole division from the sea more practicable.