Chapter 9: Bena Bena and Tsili Tsili

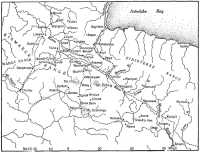

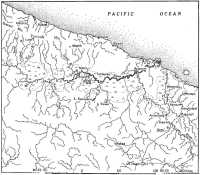

IN the hinterland of New Guinea south of the towering Bismarck and Wahgi Ranges lies a huge plateau of grasslands. It begins near Kainantu about 100 miles west of Lae by the imperceptible watershed whence the Markham and Ramu Rivers run in opposite directions, and continues through Bena Bena, Garoka, and Chimbu to Mount Hagen, a distance of about 130 miles. Beyond, it goes on to the Star Mountains and the Dutch border, a total distance from Kainantu of roughly 350 miles. The plateau, criss-crossed by many small streams and broken into numerous valleys, is seldom wider than 20 miles. Lying at about 5,000 feet, it has a bracing temperate climate, and is free from mosquitoes.

Before the war relatively few white men were established on this plateau, so strangely different to the tropical jungle mainly encountered elsewhere in New Guinea. To protect the large but untamed population from exploitation, the administration had declared the Bena Bena–Mount Hagen plateau a closed area. The natives were smaller than the Papuan and Melanesian natives already so well known to Australian soldiers. Like many primitive peoples they fought tribal wars, but they were primarily gardening folk. And what a garden they lived in! To the first band of Australian soldiers who arrived there the Bena plateau seemed like an Eden.

The Mount Hagen area had been thoroughly penetrated in 1933 by a patrol led by an Assistant District Officer, J. L. Taylor. In the next year Roman Catholic and Lutheran missionaries established themselves in the area, and other missionaries followed. Patrolling continued and, by 1941, roads had been built in the Chimbu area, where 31,000 natives had been counted, and a post established at Mount Hagen, where 22,000 natives had been counted within a 10-mile radius.

Farther west the mountain country in which the Sepik rises had been visited by relatively few expeditions. The German explorer, Dr Thurnwald, had led a party to the headwaters of the Sepik in 1914. In 1926-1927

C. H. Karius and Ivan Champion, two officers of the Papuan administration, had crossed the island from south to north, travelling up the Fly River, across the Hindenburg Range and down the Sepik.1 In 1936 and 1937 a party of seven under J. Ward Williams made a mining investigation of the upper Sepik area. This group made a landing ground in the Telefomin country on which was landed an amphibian aircraft, and, for the next five months, largely air-supplied, explored, on foot and from the air, the country round the headwaters of the Sepik.2

In March 1938 J. L. Taylor, J. R. Black and four other Europeans with about 250 natives set out from Mount Hagen towards the Dutch border. In the next 15 months this expedition covered the central highlands from Mount Hagen to Telefomin in the west and from below the Papuan border in the south to the Sepik in the north. They were supplied by parachute at one stage and made extensive aerial reconnaissances.

Thus, in miniature, several methods being used in 1943 on a larger scale had been employed in this area: supply by air transport, the dropping of supplies, and reconnaissance by land-based aircraft and flying-boat.

At the beginning of 1943 the natives in the Bena Bena-Mount Hagen country were a responsibility of J. R. Black (now a captain in Angau and the district officer for the Ramu area), and his staff of 4 officers and 9 NCOs. Black was able to recruit large teams of native carriers, mainly from the Chimbus who formed the largest numerical group of the population, but these carriers could safely be used only in the high non-malarious plateau and not in lower areas where they were likely to die from malaria. Payment for native services was made with sea shells.

At Bena Bena itself was a crude pre-war airstrip about 1,200 yards long, a fact known to the Japanese. The plateau would be strategically valuable to either side: for the Allies occupation of the plateau would help them to outflank the main enemy positions in the Huon Peninsula and Finisterre Mountains and provide emergency or advanced airfields; for the Japanese, occupation would place them on the high ground on the flanks of the main route through upland New Guinea, the Markham-Ramu valley. Early in 1943, however, both sides were recuperating after the fierce battles of the previous six months, and their resources were strained by the Wau–Mubo campaign.

Realising how close the Japanese had come to establishing themselves at Wau, and how much more difficult it would be to expel them from the interior of New Guinea than from the periphery, the Australians decided that they must occupy the plateau before the Japanese did so, even though only a small force could be employed. The Americans were interested in the plateau’s potentialities, particularly since August 1942 when Lieutenant Hampton of the Fifth Air Force landed four American technicians on the rough Bena strip to collect parts from a crashed Mitchell near by, and picked them up four days later.

Thus New Guinea Force on 22nd January 1943 had ordered the 6th Australian Division to dispatch a small force by air from Port Moresby to Bena Bena next day. Lieutenant Rooke and 57 men of the 2/7th Battalion landed at the Bena Bena strip on 23rd January from six Douglas transport aircraft.3 An operation instruction stated that the task of this small band (known as Bena Force) would be “to secure Bena Bena drome against enemy attack; to deny the enemy freedom of movement in the

The Central Highlands

Bena Bena Valley; to harass and delay any enemy movement in the area between Bena Bena and Ramu River”.

Kanga Force was made responsible for the Bena detachment and Rooke was placed in charge of all troops on the Bena plateau. Besides his own troops these consisted of the small Angau detachment under Captain Black, a detachment of the RAAF’s Rescue and Communication Flight, and “special New Guinea Force patrols” which were operating from Bena Bena. Information about the Japanese was scanty, but it was estimated that a Japanese force of about 1,000 was in Madang and was sending patrols south and South-west towards the Ramu; on 20th January about 100 Japanese were reported to be at Dumpu while a smaller patrol had attempted to cross the Ramu south of Kesawai. Not wishing to stir up the enemy across the river and invite reprisals, Brigadier R. N. L. Hopkins, then senior staff officer of New Guinea Force, instructed that “patrols of Bena Force will not cross Ramu River”.

The tiny Bena Force could hardly be expected to hold the plateau against a determined Japanese thrust, but they might delay it long enough for reinforcements to be flown in as had been done recently at Wau. For the present, however, even if more troops could be found it would be difficult to spare the aircraft to fly them in, let alone supply them. It was apparent too that it would be easier for the Japanese to supply a base on the

Bena plateau by a land route from their north coast bases than for the Allies to do so by air from their South-eastern bases.

Just as the Bulldog Road was designed to provide an overland route to Wau, so New Guinea Force had been looking for an overland route from the south coast to the Bena plateau (and thence to Lae and Madang). For instance, in September and October 1942 Lieutenant Bloxham4 of Angau had patrolled through uncontrolled areas from Kainantu across the Papuan-New Guinea divide to the Purari River and back. The Purari was the largest river draining the plateau south to the Gulf of Papua and might perhaps provide the easiest route.

In January 1943 Lieutenant Snook,5 an engineer with pre-war experience in New Guinea, summarised for New Guinea Force all available information about routes from Port Romilly on the Purari to Madang and Lae. He concluded: “The Purari–Aure River junction to Aiyura section may present some difficulties, but the remainder of the route will not be difficult, much of it being through open grass country.” After being flown over the Purari–Aiyura area in an Anson on three successive days early in February, and gleaning scanty information about pre-war tracks in the general area, Snook was ordered on 12th March to determine the feasibility of providing a pack transport route or jeep track from the junction of the Purari and Aure Rivers to Kainantu.

He arrived at Bena Bena on 23rd March and left Kainantu for the south on 7th April. About 30 miles south of Bena he witnessed the crash of an American bomber and with the aid of 300 Kesikena bowmen he found and buried the bodies of the occupants. By 1st June his party, including 12 Lutheran mission teachers, 13 Seventh Day Adventist mission teachers, and three native constables, had crossed to Port Romilly on the Purari delta. Although it would be possible to develop a jeep and motor road along portions of the route, there were other portions where Snook thought that it would be extremely difficult even to establish a pack transport route. Meanwhile, the Japanese were preparing to build a road south from Bogadjim to the Ramu over the rugged Finisterre Mountains.

As soon as Rooke’s small band arrived in January 1943 it had begun digging defences around the Bena Bena airstrip, and soon Corporal Berry led a patrol towards Kainantu where he arrived on 28th January. The force rapidly became acquainted with the people of Bena Bena and the Chimbu carriers and, as ever, the natives seemed to appreciate the Australians’ sense of humour. Soon they were helping them to build huts, chop timber for pill-boxes, and clear the kunai and crotelaria for fields of fire. By the end of January the Bena Force diarist stated that the natives were “working like tigers”, patrols were reconnoitring all approaches, and four observation posts were established watching the tracks into Bena Bena

with telephone communication to Bena airfield. One was in the Rabana area and the others close to the airfield. Attempts were made to conceal the Australian positions from the air, the airstrip was burnt in patches to resemble the surrounding partially burnt grasslands, the three-feet-deep gutters running down each side of the strip were filled in and grass allowed to grow to merge in with the airfield.

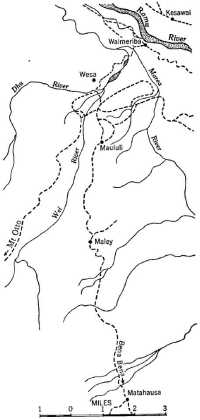

On 8th February four men left to reconnoitre the most direct route across the Bismarcks from the Ramu Valley into the plateau: the Waimeriba–Wesa–Matahausa track. Eight days later the patrol returned. “Tough trip” was the diarist’s laconic comment describing the tortuous crawl over the range between Mounts Helwig and Otto towards the river flats. A patrol to Lihona in March found a native war raging along the route. During the first two months Rooke was supplied by air, 12 transport loads arriving between 5th and 23rd February. To augment the ordinary army rations, already supplemented by native fruits and vegetables, a herd of mission cattle from Kainantu was driven to Bena Bena by two ex-stockmen in Bena Force.

Towards the end of March, when native rumours suggested that the Japanese were in Kaiapit and Sangan, Rooke moved his headquarters into the Kainantu area closer to Kaiapit. Before this there had been rumours that, in January or February, three Japanese patrols, totalling about 150 troops, had made the trip along the old trade route from Bogadjim across the Finisterres and down the great river valleys to Lae. On 2nd April Sergeant Cavalieri,6 who had left Bena on 10th March to establish a teleradio station at Onga, reported that 90 Japanese were in the Kaiapit–Sangan area. As this enemy party had not been seen in the Ramu Valley it was assumed that it came from Lae, although it would not be hard for 90 men, moving under cover of darkness or weather along the river flats, to escape observation from the few and scattered observation posts overlooking the Ramu. “The Japs having decided to return to Lae and Madang,” wrote the Bena Force diarist on 9th April, “our forward headquarters has decided to return to its base at Bena Bena.”

Native reports indicating renewed enemy interest in the Ramu area soon began to reach Angau and Air Wireless Warning posts stationed along the Bismarcks, and were radioed back to Bena. From 20 to 30 Japanese with a carrier line of 50 natives were reported at Musak some miles west of Bogadjim on 26th April; four days later they were at Sepu on the Ramu. About the same time Japanese patrols were reported to be mapping the Koropa and Kesawai areas, directly north of the main route into the Bena plateau, and to have three native working parties cracking stones, presumably for the Bogadjim to Ramu road.

Throughout May the enemy showed increased interest in the three main approaches to the plateau. Native rumours made it appear that a limited enemy offensive against the Chimbu–Bena area, using the approaches through Guiebi, Bundi and Wesa might be imminent. It seemed definite

that on 4th May a large Japanese force visited Kaigulin where it actually crossed the Ramu River. On 9th May a watching police boy saw two Japanese cross the river at Waimeriba. Next day Captain Rooke’s watching post was surprised by a party of about 15 Japanese led in by hostile natives and had its supplies captured although it suffered no casualties. On 19th May Bena Force suffered its first casualty when an Australian was killed by natives.

At Port Moresby and Brisbane Australian planners by May 1943 were anxious about the frequent reports that the Japanese were interested in the plateau. New Guinea Force estimated that the Japanese now had at least 10,000 troops at Madang with about 500 at Bogadjim, and camps in the Egoi area 30 miles west of Bogadjim. For the first time the Japanese air force began to take an interest in the plateau and six attacks were made in May over Bena Bena and the old emergency landing strips at Asaloka and Garoka. As it now seemed possible that the Japanese intended to make a road from Madang to Bogadjim and across the Finisterres to the Ramu Valley and thence to Lae, it was decided that Rooke’s tiny force must be reinforced.

As a battalion would be too difficult to supply, Major T. F. B. MacAdie’s 2/7th Independent Company was withdrawn to Port Moresby from Wau and preparations made to send it to Bena Bena. The Independent Company, which had served in the Wau area for seven months, was tired and needed a rest but no other troops were immediately available.

On 27th May MacAdie received instructions from General Herring (who had returned to command of New Guinea Force on the 23rd) to move his company by air to Bena Bena and take command of all troops on the plateau. His tasks were the same as those originally given to Rooke in January, but he was to be directly responsible to New Guinea Force and not the 3rd Division. He would not, “except when attack is imminent or in progress interfere with the general tasks of Angau and special detachments”. On 29th May the 2/7th was flown in, and Bena Force was then about 400 strong. MacAdie found that Angau was maintaining watching posts at Onga, Kainantu, Bundi, Lihona and Matahausa, but “these were not very effective as all information was from native sources and much of it unreliable”. As he became acquainted with his area during June he noted that there were four main lines of approach to Bena Bena which the enemy might follow: first, from Lae through Kaiapit, Aiyura and Kainantu; secondly, from Bogadjim over the Finisterres, and through Lihona; thirdly, from Bogadjim through Kesawai, Wesa and Matahausa; and fourthly, from Bogadjim through Glaligool, Bundi and Asaloka. He therefore directed that observation posts should be established well forward and with good communications to give the greatest possible warning; that patrol bases should be dug on each of the approaches, and that delaying positions should be prepared along the lines of approach to inflict the greatest possible delay and so enable him to concentrate at the right place once the main threat was clear. Terrain difficulties would delay a Japanese advance on Bena Bena for several days after crossing

the Ramu and MacAdie reasoned that if he had some mobility he would be in a better position to beat off an attack. He got permission to build a motor road from Bena Bena to Kainantu, to enable him to move his scanty reserves laterally and quickly.

In June he sent out patrols to test the native rumours; built huts for the troops and bomb-proof shelters for stores; recruited labour through Angau; proceeded with “extensive mapping, as existing maps hopelessly inaccurate”;7 reconnoitred the proposed vehicle route from Bena to Kainantu; and constructed a vehicle road from Bena to Garoka to link the Bena airfield with a proposed new airfield at Garoka.

There had been several pre-war airstrips besides Bena Bena dotted on the plateau from Mount Hagen to Kainantu. The small emergency strip at Garoka could not be extended, but near by there was excellent flat land for a large airstrip. Seeking an adequate fighter strip which could support raids against the enemy’s north coast bases, and divert the enemy’s attention from more important construction in the Watut Valley, the Fifth Air Force became interested in Garoka. General Kenney “didn’t care about making anything more than a good emergency field, but ... wanted a lot of dust raised and construction started on a lot of grass huts so that the Japs’ recco planes would notice”. He also ordered his air force commanders “to be sure to explain to the natives that we were playing a good joke on the Japs, that we were trying to get them to send some bombers over”.8

The Japanese made aerial reconnaissances of the general area on the 1st, 2nd and 5th June, and their aircraft began attacks on 8th June when 7 bombed Chimbu, 5 bombed Asaloka, and 8 bombed Kainantu. Further reconnaissances of the Bena–Garoka–Kainantu area on the 9th and 10th were followed on the 14th by heavy raids on the Bena Bena, old Garoka, Asaloka, Kainantu and Aiyura airstrips by 27 bombers and 30 fighters. Next day 6 bombers and 6 fighters attacked Kainantu and Aiyura, and on the 16th 18 bombers and 22 fighters attacked Bena Bena.

The attacks from the middle of June apparently pleased Kenney.

As I had hoped (he wrote later), the Jap reccos spotted the dust we were raising and the new grass huts we were building around Garoka and Bena Bena and evidently decided we were about to establish forward airdromes there. Beginning on the 14th they attacked both Garoka and the Bena Bena almost daily, burning down the grass huts and bombing the cleared strips, which looked enough like runways to fool them. The natives thought it was all a huge joke and when the Japs put on an attack they would roll around on the ground with laughter and chatter away about how we were “making fool of the Jap man”.9

To those who were actually the recipients of the Japanese bombs there seemed little reason for such mirth. In these raids three natives were killed and three Australians wounded. Force headquarters and a stores

dump at Bena Bena, the Seventh Day Adventist mission at Asaloka, and several native huts were demolished or damaged.

Despite Kenney’s pleasant fiction MacAdie was given no instructions about the wider deception strategy in his original briefing; although he had been carefully briefed by General Herring who subsequently went to the trouble of keeping MacAdie in the general picture – usually by means of a weekly hand-written letter. Very soon after his arrival, however, MacAdie realised that his whole tactical operation would have to be based on deception. If he could convince the Japanese that he was much stronger than he really was it might help to discourage them or cause them to delay an attack across the Ramu. His first deception measures, if his widespread dispositions are disregarded, were taken without reference to New Guinea Force and were designed to draw enemy air action away from Bena Bena airfield and confuse the enemy regarding the Australian intention to build an airfield at Garoka.

At this early stage it was vital for MacAdie not only to keep Bena Bena airfield in his hands but to keep it serviceable. In the first air attacks heavy bombs had cratered it and there were no resources but Chimbu labour with picks and shovels to repair it. MacAdie feared that repeated bombing might so crater it as to render it too dangerous for loaded transports, and his force would then be really isolated.

The building of the Garoka airfield required a very large labour force of Chimbus organised by Major Black’s successor, Captain H. L. R. Niall.10 If the Japanese air force were to attack Garoka while work was in progress, it would not need many Chimbu casualties to make the entire labour problem acute because the whole force was entirely dependent on Chimbu carriers.

MacAdie therefore determined to use Asaloka for deception, and to a lesser extent Aiyura. There were old emergency landing fields at both places. At Asaloka his men cut strips of kunai along the airfield as though it were about to be enlarged, kept fires burning, put up tents around the Mission building, hung out many clothes to dry, and tramped Chimbus up and down to make fresh tracks.

Early in June when MacAdie learnt that he was to be reinforced he established force headquarters at Sigoiya Mission and handed over control of the company to Captain F. J. Lomas. MacAdie decided to concentrate on the main route, and Lieutenant Byrne’s11 section was sent on 1st June over the Bismarcks toward Wesa to occupy the area. Byrne sent back a disturbing native rumour that the enemy would soon make a drive through Wesa to Bena Bena, and reported that Wesa and Waimeriba were occupied in strength and natives under Japanese direction were

burning the kunai and scrub on both sides of the Ramu. He added that natives had disclosed the position of the patrol to the enemy.

The native problem was indeed a serious one along the river front. “It should be realised,” wrote MacAdie early in June, “that the country between the Ramu River and Bena Bena is uncontrolled, unexplored and unmapped. No definite information of roads or tracks can be gained even from Major Black of Angau, who knows this area better than any man. The area is vast, and the quickest recce on foot would require months.” He considered that the natives north of the Bismarcks and south of the Ramu were “treacherous”.

Even on the plateau difficulties were being experienced with the natives. The Angau representative at Chimbu, Captain Costelloe,12 wrote at this time:

There is a spirit of unrest throughout the whole of this district and this is mainly due to the unsettled state of mind existing amongst the natives which tends to disorganise their general outlook. It is not really an “anti-British” feeling so much as a distorted and disturbed mental reaction. ... This area seems likely to become a centre of military operations in the very near future. All military activities are bound up with the amount of native labour available. The main source of native labour is the Chimbu area. At present recruits are coming forward willingly enough and are sticking to their jobs despite enemy aerial activity, but to maintain this we must keep a firm hold on the Chimbu natives and endeavour to keep them settled and controlled.

The supply of the outposts in the low area north of the Bismarcks presented a complex problem. The Chimbus were free from malaria and intended to remain so; remembering that many of those taken into the low country some years before had died from malaria the Chimbus refused to leave the high ground. Along the main route over the Bismarcks they would carry only to Matahausa, two days’ carry from the Ramu. They were not rice-eaters and needed to carry from 10 to 12 pounds of native food for each day’s ration. Thus on a four days’ carry they would be fully loaded with their own food even before they began to strive to lift cases of bully beef or ammunition. Consequently Angau brought in some lowland carriers from the Waria and Sepik Rivers to carry north of the Bismarcks to the Ramu Valley.

With its knowledge of the Chimbus’ refusal to leave the high ground, it was surprising that Angau headquarters in Port Moresby should have ordered on 13th June that 300 plateau natives be held ready to help construct airfields in the comparatively low-lying Watut Valley.

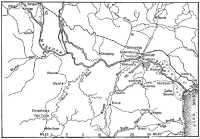

Reports now arrived of enemy patrols in Dumpu, Kaiapit, Onga and Boana, and of patrols moving south from Bogadjim across the Finisterres, from the Rai Coast across the Saruwageds, and from the North-east coast by pinnace along the Keram River to a point opposite Annanberg. New Guinea Force, however, was not impressed, and on 9th June stated that “in spite of recent native rumours, there seems to be no good reason, tactical or otherwise, why the Japanese should try to open up a track

across the Saruwaged and Finisterre Ranges which are over 11,000 feet high”. At this time it was thought at Port Moresby that it would be quicker for enemy troops to move to Lae along the coastal route via Sio and Finschhafen. In the middle of June natives reported a large enemy force apparently awaiting reinforcements before crossing the river near Sepu. From Dengaragu Lieutenant Toole’s13 section of the 2/7th Independent Company reconnoitred towards Sepu and Lieutenant Davis’14 section at Chimbu moved to Dengaragu whence the route to Guiebi and Bundi could be controlled; on 26th June the Allied air force attacked Sepu and burnt the huts.

From the Kainantu to the Sepu area both sides were now investigating the Ramu Valley. Towards the end of June Captain McKenzie’s15 Independent Company platoon relieved Captain Rooke’s infantry platoon in the Kainantu area, Lieutenant Reddish’s16 platoon was defending the Garoka area and Lieutenant Byrne’s was divided between the Matahausa, Bundi and Dengaragu areas. MacAdie had little reserve to reinforce the troops who might meet any Japanese advance over the mountains before the completion of the vehicle road and his hold on the vast and pleasant plateau was therefore very tenuous.

At the beginning of June General Herring suggested to Generals Blamey and Kenney that Bena Force should consist of a battalion and an Independent Company, with light anti-aircraft guns to protect the area so that fighters could be brought forward, but when Kenney decided that he could not maintain a force of more than 1,000 on the plateau Blamey decided to send in another Independent Company – the 2/2nd. The 2/2nd was already on the move from Canungra to the II Australian Corps area on the Atherton Tableland where the 2/2nd, 2/4th and 2/6th Companies would come under command of a newly created headquarters for Independent Companies known as the 2/7th Australian Cavalry (Commando) Regiment, originally the 7th Divisional Cavalry.17 Six months exactly since returning emaciated from a year-long guerilla fight in Timor, the company, under the command of Major G. G. Laidlaw, set sail for Port Moresby where it arrived on 20th June. A week later Laidlaw’s headquarters and one platoon were loaded into 10 transports and escorted by Lightnings over the swamp and meandering rivers of the southern Papuan coast, across the towering mountains of central New Guinea, and over the rolling grasslands of the plateau. Company headquarters moved to Garoka at the end of June, to be greeted three days later by a bombing attack which killed one native and wounded two others. On 8th July a

second platoon and others landed at Garoka and Bena Bena at the same time as enemy bombers and fighters appeared in the area.

During the landing (wrote the company’s diarist) escorting Lightnings drove off nine enemy bombers and some fighters attempting to raid the aerodromes. ... At Bena Bena, while transport planes were circling preparatory to landing, one enemy recce plane, by mistake, joined the formation. It was last seen heading east at high speed with three Lightning fighters in pursuit.

Captain Rooke’s small force returned to Moresby in the transports. The remainder of the 2/2nd Independent Company had arrived by 1st August, by which time it numbered 20 officers and 274 men.

On 29th June construction work on the new Garoka airfield began under the supervision of the engineer sections of the 2/2nd and 2/7th Independent Companies; anti-aircraft, wireless and radar positions had been established soon after the arrival of a party of Americans under Major Homer Trimble on 12th June. With the assistance of Angau and 1,000 natives, the engineers built the airfield-6,000 feet long with dispersal bays – in seven days.

Meanwhile, MacAdie ordered Laidlaw to defend the new Garoka airfield, occupy the Chimbu and Asaloka airstrips as “anti-paratroop bases”, build a road from Asaloka to Chimbu, oppose any enemy crossing of the Ramu between Sepu and Yonapa, and patrol across the Ramu into the area bordered by Sepu–Glaligool–Usini–Urigina in an attempt to secure more reliable information about the enemy than was being provided by native reports. On 7th July Laidlaw informed his company that they would operate to the west of a North-south line through Sigoiya; the 2/7th would operate to the east. He instructed Captain T. G. Nisbet’s platoon to occupy Dengaragu and Bundi, Captain C. F. G. McKenzie’s platoon to occupy Chimbu, Asaloka and Kortuni, and Captain D. St A. Dexter’s platoon to remain in the Bena Bena area in reserve.

There was now a sudden increase in Japanese activity south of the Ramu. A message was received by a native police runner that the observation post at Lihona had been overrun by the Japanese before dawn on 7th July. Two days later an enemy patrol overran another of the 2/7th’s observation posts in the Sepu area. Two Australians were wounded including Private Rofe.18 Reports of 100 Japanese at Marawasa on the same

day, other patrols at Bumbum and Arona, and an enemy attack on “Snook’s House” where two Australians and four Japanese were killed, caused MacAdie (now a Lieut-colonel) to warn all posts to take precautions against surprise, particularly when the kunai grass along the Ramu was burning. By 11th July a patrol to Lihona established that two Australians had been killed and mutilated and two Japanese killed. The police boy, Woisau, who had been captured on the 7th but escaped, told the patrol that 16 Japanese and 9 Kaigulin natives had made the attack. It was apparent that the Japanese were being aided by the riverside natives; not otherwise could they have exhibited such accurate knowledge of the Australian positions and such skill at finding them by dark after advancing through the bush.

Other reports of native cooperation with the enemy were brought back by Corporal Merire who arrived exhausted at Bundi on 12th July from a memorable patrol into the heart of enemy territory near Ma dang. A stretcher party was sent out for his companion, Constable Kominiwan, who had been wounded and hidden by Merire. Merire made a full and convincing report of having seen a motor road from Bogadjim to Mabelebu, a “coolie track” thence to Boroai, 4,000 “coolies” constructing the road, 1,000 carrying supplies, 60 motor vehicles, and supply dumps. He reported that the Japanese were treating the natives very liberally and with good effect. This underlined one of MacAdie’s main worries – the labour problem. “Stocks of trade [mainly shells and salt] are at present nil,” wrote MacAdie to General Herring on 21st July, “and we are compelled to beg reluctant natives for credit for food supplies and labour – a deplorable situation when we are compared with the powerful and open-handed Nippon soldier, and until MT is functioning (on roads which the native is building) we are essentially dependent on the generosity of a population which owes the ‘Allies’ little or no allegiance.”

The Japanese now left their newly-captured positions south of the Ramu and Lieutenant Byrne established two small five-man patrols at Wesa and Waimeriba. At 1.30 on the morning of the 17th, however, the Japanese recrossed the river, and, led in by natives, surprised the Waimeriba patrol. The five Australians escaped but two natives were killed and three wounded. Byrne then realised the vulnerability of the Waimeriba flats and established his section of 24 men on the higher ground near Wesa.

The next message from this front – that a carrier line had been ambushed between Matahausa and Wesa – caused uneasiness at Sigoiya. MacAdie decided to use his reserve and instructed Laidlaw to send Dexter’s platoon to take control in the Matahausa–Wesa area on 20th July.

Just as the platoon left Bena Bena early on 20th July enemy bombers and fighters attacked the airstrip and burned most of the huts. From this time on there was much activity in the air. Fleets of Allied bombers and fighters used the river valleys as their main landmarks, giving Australians north of the Bismarcks a grandstand view, while smaller groups of Japanese bombers and fighters worried the airstrips on the plateau. Often aircraft were heard but could not be seen because of lowering clouds. MacAdie’s deception tactics were certainly causing the enemy air force to waste a considerable amount of effort in sporadic air attacks on the plateau.

With two of Laidlaw’s platoons moving to the river front MacAdie sent a progress report to Herring in which he reasoned that

there would seem little doubt that the enemy assess the size of Bena Force as well in excess of the actual figures. The constant building activities and rapidity of road construction as seen by his recce aircraft coupled with the fact that he has encountered our troops at four points on a line over eighty miles long is bound to affect his estimate considerably. It seems probable that he will regard this force as a definite threat to his new road.

By the evening of 21st July Dexter’s platoon and the 150 Chimbu carriers had reached Matahausa after climbing over the Bismarcks. A diarist described this climb:

Mount Helwig on right, Mount Otto on left – absolute bastard of a climb – dank, dark, dripping, rain forest – ancient moss covered trees looking like beeches – leeches – very cold – no natives – black mud and roots – awfully graded track – mist – up and then down terrible track – track beyond description.

It seemed to the incoming platoon that, if this was the most direct route from the Ramu to the plateau, Bena Force was reasonably safe. Captain Nisbet’s climb over the Krakemback into the Bundi area was no less onerous.

By 24th July Nisbet relieved the detachment of the 2/7th in the western area and established his headquarters at Bundi-Crai with sections at Bundi, Guiebi and Dengaragu. Dexter, aided by Byrne, was reconnoitring Wesa and Waimeriba. It seemed that bases nearer the river must be established to prevent the Japanese getting a foothold on the Bismarck tracks. Matahausa in the rain forest, whence patrols had previously operated, was two days march from the Ramu, and had no fields of fire or good observation posts. The half-way camp now known as Maley19 was better but still too far back. At the end of the month a new site, Maululi,20 was selected near the northern tip of the Matahausa spur which ran towards the Ramu between Mounts Helwig and Otto. Here

on the verge of the jungle a strong defensive position commanding approaches from the Ramu and affording good observation posts was established.

Trouble with the natives began to flare up, but fortunately an experienced Angau representative, Captain O’Donnell,21 now came forward to look after native affairs in the Wesa area.

The history of the Matahausa–Wesa area had been one of bad management and some tragedy (wrote O’Donnell later). The pre-war history of the natives was of truculent groups with some experience of European plantation ways, very infrequently patrolled or visited by Government officers and, consequently, contemptuous of the authority of the Administration.

Soon after the Japanese invasion of the north coast of New Guinea a large cargo including rifles and ammunition had been carried from Madang by Sergeant Burnet22 and hidden at Wesa, where there was a tiny overgrown airstrip and where houses were erected. Early in 1943 Sergeant Golden23 and two men from the 2/6th Independent Company had taken over a watching brief in the area from men of the New Guinea Volunteer Rifles. In face of a native warning in May that a large enemy force was approaching, Golden withdrew from Wesa. During his absence the local natives raided the dump, stole the rifles and ammunition, and burned the huts. After attempting to salvage some stores despite enemy opposition Golden withdrew to his signals post not far from Wesa. Very ill, he and his police boy were in a lean-to near Wesa when they were awakened by four Japanese who had been led there by the local natives. Golden was killed but the police boy escaped to Matahausa.

It was the attitude of the riverside natives as well as the unfortunate experiences of Byrne’s patrols and others that caused MacAdie to suggest firm action against the natives. Hearing many shots on the Helwig and Otto spurs, obviously fired by natives, and exasperated by the cutting of his telephone line, Dexter cleared the area, when necessary, by shooting first and asking questions afterwards. After several arduous and perilous patrols, including one by Captain O’Donnell (with bare feet) and three police boys, the natives were brought sufficiently under control, at least to the extent of keeping well clear of the Australians.

Early in August Australian patrols were watching the three main approaches to the plateau from the Kainantu, Wesa and Bundi areas. A huge area was patrolled: for instance, on the right flank Lieutenant Danne’s24 patrol of the 2/7th Independent Company investigated the activities of a Japanese patrol at Snook’s House, while 100 miles away on the left flank Lieutenant C. D. Doig’s section from the 2/2nd patrolled the Sepu area where there were periodic reports of Japanese activity.

At this time obstructions were placed on the Mount Hagen and Ogelbeng airstrips. The enemy was thought to have paratroops in New Guinea, and MacAdie was warned that they might use them to seize Bena Bena and Garoka airstrips as a prelude to the landing of airborne troops. MacAdie did not regard the warning very seriously but took normal precautions and issued a plan for dealing with paratroop landings.

It was now quite apparent from air photographs that the “Bogadjim Road” had been rapidly built by the Japanese as far as Daumoina, and it seemed that the enemy intended to drive the road up the valley of the Mindjim and not, as at first thpught, across the dividing range at Boroai and down to Kesawai on the Ramu. The pilot track had apparently been constructed as far as Paipa. Should the route then follow the Uria Valley a considerable amount of bench cutting would be necessary as both banks of the Uria were precipitous for 7 miles beyond Paipa, but from there on the gradient would be easy. On 1st August it was estimated at New Guinea Force headquarters that the Bogadjim Road could reach Dumpu in six to eight weeks. Although the route from Dumpu to Lae would then lie along the flat valleys of the Ramu and Markham Rivers, at least seven rivers would require bridging or ford construction before a motor road through to Lae would be possible, and three of these – the Surinam, Gusap and Leron – were wide, deep, swift-flowing streams. As little timber was available, the Japanese engineers faced a big task. In August 1943, however, the Bogadjim Road was regarded as a growing threat.

On 8th August a small patrol led by Lieutenant Hawker25 of the 2/7th arrived at Wesa to reconnoitre the Bogadjim Road. Early on the 11th Corporal Merire, who had been reconnoitring the Waimeriba crossing, met some truculent river natives some of whom he shot with the revolver concealed under his lap lap. He was not happy about the Bogadjim Road trip and did not think the patrol would get through. During the night 11th–12th August the Australians at Matahausa, Maley and Maululi heard firing from the direction of Wesa.

On the evening of the 11th–12th the usual guards were posted at Wesa by Lieutenant Beveridge26 and a moonlight patrol searched the area until the three-quarter moon set soon after 2 a.m. At 2.15 a.m. Lance-Corporal Marshall27 and Lance-Corporal Monk28 relieved the guards on the track leading up to the Wesa perimeter from the main Waimeriba–Maululi track. Fifteen minutes later Monk heard a rustling about five yards away. As such sounds were not unusual he whispered to Marshall that he thought it was a wild pig, but a few seconds later the men heard whispering. Monk silently moved from his position by a log on the side

of the track to the cover of the roots of a big tree. Peering over the roots, he saw, against the eerie blackness of the night, a whitish figure crawling up the hill on hands and knees about a yard from where he had been sitting on the log. Monk trained his rifle on the ghost-like figure. Marshall called “shoot” and threw a grenade, while Monk squeezed the trigger and saw the figure disappear with a muttered groan as though hit. Both men then took aim down the track, fired a shot each and then threw grenades at a spot where they assumed others would be following the forward scout. They shouted to their section above to be prepared and streaked up the hill to where the men had already entered their fire pits. Then there was stillness punctuated two minutes later by a lone pistol shot. In the morning a dead Japanese officer and a dead sergeant, both well-conditioned men, were found at the foot of the Wesa hill. The officer, who had a neat bullet hole in his forehead, was wearing two shirts, the top one with a white square sewn on it.

After these discoveries a police boy accompanied a patrol led by Corporal Foster29 which followed blood trails towards the Wei River where Foster reported hearing the enemy whistling. A patrol was sent out to repair the telephone line, which had been cut. From Maululi Corporal

Maley’s30 sub-section set out to reinforce Wesa and to find out what had happened.31 Soon after he arrived at Wesa, Maley left his sub-section with Foster at the camp and went on to report to Beveridge who was with Hawker at the section’s observation post manned by two men. While the five men were yarning at the observation post they heard a machine-gun open up from the direction of the camp soon after 11 a.m.

Maley’s sub-section had walked rapidly and the men were out of breath when they arrived at Wesa. They gathered round Foster’s men who were busy improving their weapon-pits and discussed the night’s activities while the inevitable brew of tea was being prepared. Someone called “Come and get it”.

As though this were a challenge an enemy machine-gun opened up on to the huts from about 30 yards. Everybody dived for cover. Several of the newcomers, not being familiar with the defences, slid down a steep 40-foot slope behind the huts where they were unable to take any part in the fighting.

The moment chosen by the Japanese for the attack could not have caught the Wesa defenders less prepared. One sub-section was on patrol; the reinforcing sub-section was out of the picture; and of the remainder the section commander and some of his men were at the observation post. Foster’s sub-section numbered eight, but four who were nearing the cookhouse for a cup of tea when the first shots were fired found themselves at the foot of the steep slope with the newcomers. Foster dropped to the ground near the signals hut where he had been winding cable from a reel and, armed only with a pistol, crawled three yards to his fire pit where his Owen was. As he moved to the pit he saw about a dozen Japanese rushing towards the cookhouse from the direction of the observation post track. Simultaneously, Private Palm,32 who had been yarning in the section headquarters hut, ran past Foster, picked up a Bren left by the incoming sub-section and charged the Japanese with the Bren at the hip. Unfortunately the gun was not cocked and the speed at which Palm was moving in the few yards separating the cookhouse from the other huts did not permit him to cock it. At the last moment before colliding with the Japanese he veered over the cliff.

Meanwhile, Foster was in position to make a lone stand. The Japanese justifiably thought that they had surprised the Australians but erroneously thought also that they had captured their objective. As they gathered near the cookhouse Foster from a distance of about 15 yards fired a full magazine from the hip into their midst and saw at least five fall. The survivors made off into the undergrowth.

At this stage “there seemed to be some confusion in the attack, with much shouting and blowing of umpires’ whistles and shooting from the vicinity of ammo dump”. For a short time the covering fire supplied by

a mortar and a machine-gun ceased, but soon these weapons opened up from a new position towards which Foster hurled grenades. Then the Japanese attacked again towards the cookhouse and near-by sub-section hut this time with fixed bayonets and led by an officer brandishing a sword. Obviously they thought that the Australian defences, like their own, would be under the huts. This attack was more sustained than the first but again the cool young corporal drove them back after firing three magazines from his Owen and hurling a number of grenades.

There was now a short lull while the exasperated Japanese regrouped and Foster tried to rally his scattered sub-section. When the next attack was launched Private Giles33 from the guard post along the main track was alongside him and Private Sharp34 had wormed his way into the other sub-section trench near the cookhouse. For a third time the Japanese were driven back, unable to withstand the concentrated sub-machine-gun and rifle fire and grenades of the three defenders.

Disorganised by this gallant stand the Japanese frantically attacked the cookhouse area again, and, shouting among themselves, dragged away their casualties under cover of machine-gun and grenade fire. They attacked twice more before they finally withdrew towards Mount Otto about 40 minutes after the first attack, carrying their wounded, several of whom were found dead in succeeding days.

While Foster was writing a note to the platoon commander and Captain O’Donnell was rounding up the natives, Private Timmins35 returned to the camp along the track from the observation post and reported how the five men from the observation post had tried to return to the camp in open formation along the axis of the track. When they reached the edge of the kunai they crossed the saddle between the observation post and Wesa. As they began to climb the Wesa hill, Maley, who was bursting through the scrub in front, was killed by machine-gun fire. Hawker met a Japanese on the track but his carbine jammed, his revolver misfired and the Japanese escaped – only temporarily, however, because a grenade hurled by Lieutenant Beveridge dispatched him. The five men had probably stumbled into the rear of the Japanese attack and had caused the confusion that occurred between the first and second attacks. Hawker was shot in the back and, unable to break through the Japanese ring, the two other men retired to the head of a near-by gully while Private Timmins became separated from them and returned to the observation post. When he returned to the section Lieutenant Beveridge decided to withdraw to Maululi because his ammunition was too low to withstand another attack, he had a wounded man, and, as he stated in his report, the Japanese “are able to get right up to us without our knowledge.”

By 14th August, however, patrols found Wesa clear. By 17th August the track taken by the Japanese raiding party from Waimeriba up the Wesa Track to the Marea River, then up the Marea, Wei and Dhu36 Rivers to the rear of Wesa, had been followed by patrols.

Patrolling was intense in August. Sergeant Davies37 led his section from Asaloka via Kortuni and Mount Otto to Maululi, an almost intolerable week-long trip. To replace Lieutenant Hawker on the patrol to the Bogadjim Road Lieutenant C. J. P. Dunshea of the 2/7th arrived at Maululi on 18th August; he set out alone on the 21st, crossed the Ramu, but was fired on, and returned next day. Corporal Harrison38 of the 2/2nd led a three-man patrol on the 23rd through Sepu and then along the Glaligool Track for about a quarter of a mile before contacting the Japanese. Private Smyth39 and another man of the 2/2nd were 200 yards beyond the Ramu crossing on 25th August when they encountered about 10 Japanese and withdrew after having felled six of them. One of the main obstacles to successful patrolling in this area was the Ramu River – about 200 yards wide and flowing fast. The crossing of the river by small patrols in log canoes and rafts unsupported by fire power and little knowing whether they would be under observation by the enemy known to be in the area was in itself an achievement.

MacAdie now decided to see the direct route for himself and visited Maululi on 28th August. While he was climbing the Bismarcks, action was taking place at each end of his huge domain. A patrol led by Captain N. B. McKenzie from his platoon of the 2/7th in the Kainantu area, having discovered that an enemy patrol from Arona 1 visited Arona 2 daily, ambushed it on 27th August and killed six Japanese without loss. Far to the west, the boot was on the other foot, when an enemy patrol surprised Captain Nisbet’s observation post at Faita early on the morning of the 27th and killed three men.

All the Japanese activity along the north bank of the Ramu and sometimes on the south bank was part of a pattern. General Adachi intended to capture Bena Bena, and, as secondary objectives, Kainantu and Chimbu. He planned that the 238th Regiment based at Dumpu (and less the detachments round Lae) would capture these areas early in September, supported by a battalion of mountain artillery, engineers and perhaps paratroops. The main enemy attacks would be made from Kesawai and Dumpu along the Wesa–Matahausa track and along the Lihona–Mount Keyfabega track. Smaller detachments would attack from Kaireba along Sergeant Davies’ route over Mount Otto to Asaloka, while the third battalion would attack Kainantu from Marawasa. When the Bena Bena and Kainantu areas were captured the regiment would exploit to Chimbu.

Further indications of the Japanese intention to attack the plateau were contained in a captured document in which the 20th Japanese Division was depicted in Lae with an arrow pointing up the Markham Valley with a note “to Bena Bena”. As late

Tsili Tsili-Nadzab area

as August Adachi intended to move into the Bena Bena plateau, but the troops required for this task (20th Division) were soon needed urgently elsewhere. As far back as 17th June an “Imamura Force Order” had stated that “a great enemy air force is located in the Bena Bena-Mount Hagen area. Our air force in close cooperation with the army is striving to break down the enemy positions.”

The Australians would not have been surprised had the Japanese crossed the river in force. The enemy may have gained some initial success, perhaps in the more accessible Kainantu area, but from the choice of his routes for the main task he would be inviting another such disaster as befell him at Wau. Sergeant Davies particularly might have been inclined to advise that the detachment crawling over Mount Otto should be left

to its fate. The Australians, indeed, would have found a Japanese attack a change from their arduous patrolling. The real noises of battle would then have replaced the rush of the cassowary through the scrub, the startling machine-gun rattle of the hornbill, the crashing of falling limbs and trees, and the noises of wild pigs, Goura pigeons, flying foxes and birds of paradise.

East of the Bena plateau in the valley of the Watut, preparations to support the Australian offensive into the Markham Valley were being pushed forward rapidly. When the plans for the Lae and Nadzab offensives were first mooted the Allied commanders realised that it would be necessary, as a preliminary, to knock out the enemy’s air force. As Wewak had become

the enemy’s main air base in New Guinea, an area from which escorting fighters could operate to protect the Allied attacking bombers was needed. General Kenney later described his efforts to secure such a base:

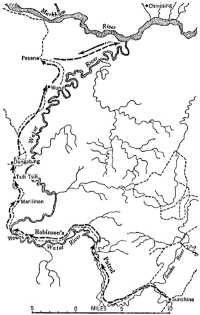

Ever since we first began to talk about capturing Lae and Salamaua, back during the Buna campaign, we had been looking for a place to build an airdrome close enough to Lae so that our fighters could stay around to cover either an airborne or seaborne expedition to capture those important Jap holdings. ... Whitehead finally located a flat spot along the upper Watut River, about 60 miles west of Lae and near a native village marked on the maps as Marilinan. It was a pretty name, the site looked good, and it was ideally located to support operations to capture Lae, Salamaua and Nadzab.40

Early in May 1943, General Savige, conscious that one of his tasks was to guard the Wau–Bulolo area from all directions including the North-west via the Watut and Wampit Valleys, had flown along the Wampit Valley and then west to the junction of the Watut and Markham Rivers and south to Sunshine He was impressed by the apparent ease with which aircraft could land in the Watut Valley and by the excellent track on the western edge of the wide, flat valley. This track had been improved soon after the Japanese invasion by Warrant-Officer Lumb41 who had penetrated to the coast near Madang, rounded up cattle, and overlanded them across New Guinea to Edie Creek.

Anxious to find out what the track and valley were like and whether the Japanese were infiltrating or patrolling the valley, Savige ordered the 24th Battalion which had been in his area for about a fortnight to supply a patrol. Lieutenant Robinson was chosen to lead it – a section of eleven men, a police boy, and native carriers. They set out from Sunshine on 7th May. The Angau officer who was to act as interpreter was ill and could not go, and, with but a rudimentary knowledge of pidgin, Robinson pressed on across country not yet entered by the army; on the third night he entered Wowos and next day crossed the Watut over Lumb’s cattle bridge.42 From the top of the ridge at the end of the upper Watut the men gazed down into the broad valley of the lower Watut with its kunai plains, villages, creeks and swamps. They entered Marilinan that evening.

As this was the first patrol to enter the Watut area since the Japanese landed Robinson decided to “show the flag”, and next day entered the villages of Tsili Tsili, Dungatung and Wuruf in military order and with fixed bayonets, to be greeted by the village dignitaries with the offer of the milk of green coconuts to drink. Next day Robinson met Lumb at Pesen, and he spent two days in the area reconnoitring to the junction of the Markham and Watut and collecting information.

Private Langford of the battalion’s Intelligence section used a camera, a valuable forethought on the part of the Intelligence officer, Lieutenant

24th Battalion patrol from Sunshine to Markham River, 7th–26th May

Bunsell,43 to take snapshots of the Watut area. Having finished its task, Robinson’s patrol returned with maps and photographs by the same route to Sunshine where it arrived on 26th May. Three days later an American air force reconnaissance party consisting of Major Cox, Captain King and Lieutenant Everette E. Frazier arrived at Sunshine. They were looking for an operational or staging fighter airfield north of Wau and had been unable to find anything suitable in the Wampit Valley. At battalion headquarters they heard about the Watut Valley’s possibilities and Lieutenant Robinson was summoned to enlarge on sections of his report dealing with Marilinan and Tsili Tsili. The upshot was that Robinson took Frazier on a quick reconnaissance of the area. By travelling light they arrived at Marilinan on 2nd June after two days and a half. Frazier decided that the old overgrown airstrip, although blocked on one end by a mountain, would be able to take transport planes and fighters. Robinson organised the local natives to prepare the airstrip by cutting the kunai and filling in the holes. On 6th June Cox and King arrived on foot and after reconnoitring the general area decided that Tsili Tsili was the more suitable spot for an air base. Natives were then set to work cutting and burning the six-feet-high kunai in a 100-foot wide swathe for about 1,200 feet while Robinson and Frazier returned to Sunshine.

Next day Savige sent Robinson with Frazier to Port Moresby to assist the American air force with his knowledge of the country and in any other way possible. Frazier stated that Marilinan and Tsili Tsili could probably be used only until heavy rains began in September, and

all equipment would then have to be taken out or abandoned until the end of the rainy season. “But it could be anticipated that by that time the Allied advance ... would have reached Nadzab, a site already selected on the advice of Australians familiar with New Guinea as ideal for a permanent air base. The schedule would be tight, but it was believed that preparations could be completed at Nadzab in time to make the transfer before the rains made the move from Marilinan impossible.”44

As a result General Paul B. Wurtsmith and Lieutenant A. J. Beck landed two aircraft on the Marilinan strip on 13th June. Wurtsmith agreed that, although Marilinan could be lengthened a little more, it would be able to take nothing larger than Dakota cargo aircraft. He agreed with Cox and King, however, that Tsili Tsili was an excellent site, which could be made into an airfield with double runways 7,000 feet long and with plenty of room for dispersal areas. In order to act as guide, Lieutenant Robinson flew to Marilinan with the advanced party soon after Wurtsmith’s and Beck’s experimental landings. There he remained for three weeks assisting in locating camp sites and dispersal areas.

Construction began at Marilinan on 16th June when American engineers and a platoon of the 57th/60th Battalion were landed. By 20th June the Marilinan airfield had been sufficiently enlarged to land transports and a road had been constructed to Tsili Tsili where the engineers began work on the real air base. By 1st July Dakotas were able to land there. Within 10 days these dependable planes flew in a company of airborne engineers with miniature bulldozers, graders, carryalls and grass cutters. Before the end of July the new base was capable of handling 150 Dakotas a day.

On 26th July the first fighters landed at Tsili Tsili; on 5th August Lieut-Colonel Malcolm A. Moore (replaced on 27th August by Colonel David W. (“Photo”) Hutchison) assumed command of the Second Air Task Force in the Watut Valley where, by the 11th, there were about 3,000 Allied troops; on 17th August Herring established Tsili Tsili Force under the command of Lieut-Colonel Marston of the 57th/60th Battalion.45

Herring had made it clear to Marston in June that the Australian commander would be operationally responsible for the Tsili Tsili area. By using tact and common sense, and with the cooperation of the American commanders, Marston worked out his defensive plan so that the exceedingly liberal armament of every American air and construction unit would be used to the best advantage. One supply squadron had so many weapons that the American commander did not know what to do with them. It soon became obvious to Marston that “if someone didn’t coordinate and prepare a fire plan, if the necessity arose for the use of this plethora

of weapons, a proper hellzapoppin would be the result”. When the Americans knew what was wanted they set about implementing it in typical style. Moore lent Marston his Piper Cub aircraft for reconnaissance; Lieut-Colonel Murray C. Woodbury of the 871st US Airborne Engineer Battalion whose task was to construct the strips on a 24-hour schedule working at night under arc lights set his dozers and graders to work cutting fire lanes and fields of fire.

It would appear that the Japanese were deceived as to the relative importance of the airfields in the Bena Bena and Tsili Tsili areas. At least, they had no firm plan to capture Tsili Tsili as they did Bena Bena. Thus MacAdie’s deceptive tactics were successful, as was also Kenney’s idea that “if the Nip really got interested in the Bena Bena area, he might not see what we were doing at Marilinan”.46 Camouflage and clever flying by pilots also helped to hide the full significance of Tsili Tsili from the enemy until their two raids in mid-August, despite Tokyo Radio’s warning that Tsili Tsili would be bombed on 25th July. “My fingers by this time were getting calluses from being crossed so hard,” wrote Kenney, “but the Japs still showed no signs of knowing that we were building a field right in their back yard.”47

Before the establishment of Tsili Tsili Force on 17th August Australian and Papuan troops had not occupied positions forward of the Waffar River. To protect the Tsili Tsili airfield and to prevent the enemy using the tracks between Tsili Tsili, Pesen and Onga, Marston now decided to move his battalion forward. In its two months’ sojourn in the Watut Valley, patrols from the 57th/60th had seen no Japanese between the Watut and Onga, although natives reported sporadic enemy patrolling into the Chivasing, Kaiapit and Sangan areas.

The Amami–Onga area now claimed Marston’s attention. In August, at Amami where the high mountain spurs gave way to kunai flats, Lieutenant Frazier, Warrant-Officer Ryan of Angau and a small party of natives had made a small airstrip soon used by both American Piper Cubs and the RAAF Tiger Moths – the only means of supplying troops in the area. From Amami to Onga the flat country was suitable for the establishment of a jeep track, and at Onga tracks to Kainantu, Kaiapit and Pesen converged. Marston considered that an enemy force would have little difficulty following the track Onga–Amami–Pesen–Tsili Tsili. He therefore redisposed his force to meet this threat.48 Early in September one company was in the Amami–Onga area, where they improved the strip

to make it capable of taking transport aircraft; this solved the supply problem particularly when a jeep was landed to carry supplies forward to the platoon at Intoap, five hours’ walk away. This company also patrolled to join up with a patrol from the 2/7th Independent Company. A second company was in the Waffar–Markham–Pesen area, while the other two were disposed round Tsili Tsili and Marilinan.

Throughout 1943 several Intelligence groups were operating behind the Japanese lines in the areas with which this volume is chiefly concerned. A few examples will illustrate the type of work carried out by these groups and the dangers confronting them in hostile territory.49

Behind Finschhafen two coastwatchers, Captain L. Pursehouse (Angau) and Lieutenant McColl50 (RANVR) had in March 1943 witnessed the battle of the Bismarck Sea. A month later McColl, when walking down a path from their hut, was surprised by enemy fire from a near-by clump of bamboos. He fired a magazine from his Owen into the bamboos and then doubled back to the hut. In his haste he slipped and fell whereupon several Japanese rushed in firing to finish him off. Regaining his feet and still clutching his empty Owen he reached the jungle where he watched the Japanese surround the house and capture it empty. McColl rejoined Pursehouse at their rendezvous and, as it was obvious that their position had been given away to the Japanese by the natives, they were ordered to Bena Bena.51

To the west Lieutenant L. J. Bell (RANVR) and Sergeant Hall52 were watching the enemy along the Rai Coast near Saidor. A party led by Captain Fairfax-Ross53 was in the process of relieving the two men in February when natives led Japanese to the Australians’ camp at Maibang. In the ensuing melee Fairfax-Ross was wounded but the two parties managed to fight their way out. Natives then led the Japanese to the supply hide-outs and killed Bell and two others. The remainder of the men then made the arduous journey back over the forbidding Saruwageds to Bena Bena.

At the beginning of 1943 Lieutenant Greathead’s54 party had clashed with Japanese patrols near the lower Ramu and had withdrawn to

Area of Mosstroops’ operations

Bena Bena. By mid-March the party had arrived again on the Ramu about 60 miles from its mouth. Supply difficulties were aggravated when a plane guided by Flying Officer Leigh Vial crashed in the mountains killing all aboard. Greathead was then ordered back to Mount Hagen to hold the airfield if Bena Bena was lost.

A difficult and hazardous patrol by Private Curran-Smith,55 accompanied by Private Hunt56 and Warrant-Officer England57 of Angau had left Bundi in March 1943 for Atemble, Mugunsif, Josephstaal, Apowen, Mosapa and Wasambu areas. Living in this area until August among natives of whose feelings they were not certain, the men were a prey to the many rumours which any man who has been isolated in enemy territory will readily remember. The patrol gathered much valuable information but it lived on its nerves, as for most of the period each member

was in a separate area from the others and was accompanied only by police boys. Persistent reports of the enemy’s intention to occupy Atemble culminated on 12th August when a party of about 20 Japanese attacked Curran-Smith in the Josephstaal area. He escaped across the Assai River, was lost for three days in the jungle, and suffered from malaria before finding Greathead’s camp at Mount Hagen.

Far in advance of the battle areas and scattered round the periphery of New Guinea most of these small parties were, naturally enough, experiencing difficulty with the natives. Captain Ashton’s58 party had been flown to the Sepik at the end of February and had headed for Wewak until the men learnt from friendly natives that other natives, not so friendly, were leading two parties of Japanese from Wewak to look for them. Ashton then retraced his steps endeavouring to get far enough from Wewak to deter the enemy from following. Early in April while they were changing their sweat-drenched clothes in a native village and while Lieutenant J. McK. Hamilton was adjusting his transmitter, there was suddenly a yell and a fusillade of shots poured into the hut. Half-dressed the party dashed out the back door just as a grenade came in the front. Hamilton became separated from the others and followed the first creek he found towards the Sepik. He waded through the mud by night and at dawn rolled in the mud as a protection against mosquitoes as he slept. Four days later he reached Marui on the Sepik and was fed and clothed by Father Hansen, a day before the other three members of the patrol reached this haven, having travelled without equipment, boots and food. The party was evacuated by Catalina at the end of April.

The Sepik and Wewak areas about which the Allies were anxious to obtain information were proving trouble spots. A party led by Lieutenant Fryer59 and accompanied by a Dutchman, Sergeant H. N. Staverman of the Netherlands Navy, and an Australian, Sergeant Siffleet,60 arrived in the well-populated Lumi area south of the Torricellis in July. After reaching Lumi, Fryer and Staverman parted, Fryer to remain in the general Sepik area and Staverman to penetrate across the border into the hills behind Hollandia. Once again the unreliability of the natives led to failure. Fryer’s party was trapped by apparently friendly natives a few miles south of Lumi. The Australians managed to beat off the attack, but in the process their carriers deserted and seven weapons were lost. The party escaped south and joined Lieutenant Stanley’s61 party at Wamala Creek, a tributary of the Yula River. Fryer and Stanley then sent a signal asking for retaliatory action against the offending villages. After some delay a strafing attack was carried out in mid-September by two Lightnings on empty bush and near a friendly village.

Meanwhile Staverman and Siffleet with two Indonesian soldiers had crossed the Torricellis early in July. Learning of the Japanese patrols searching for Fryer they warned him by radio before setting out for the Dutch border. During August and September little was heard from them but at the beginning of October Siffleet, who had been left with one Indonesian at Woma, signalled that Staverman and the other Indonesian had been killed by Japanese guided by unfriendly natives. Siffleet stated that he and his companion would destroy their codes and withdraw south across the Bewani Mountains. He was instructed to proceed to the Wamala Creek base but nothing further was heard of him until it was learnt that he had been captured.

From the hills behind Finschhafen across the Saruwageds to the Rai Coast near Saidor, south across the Finisterres to the Ramu, west to the Sepik and outside the Japanese strongholds of Wewak, Aitape and Hollandia, these brave men gathered what information they could. Information useful for the air attacks on the Wewak area and the assault on the Huon Peninsula was gathered at the cost of several lives. These parties were often dogged by ill fortune and handicapped by the unreliability of the natives, but a share in the success of the Allied armies in New Guinea was their reward.

Enemy activity and intentions in the Sepik area were of great interest to both General MacArthur’s and General Blamey’s headquarters and both were keen to find out more. To General Herring on 28th June Blamey wrote:–

It is extremely important that we should get further information concerning enemy activities in this area, and do everything possible to enlist the natives on our side, or at least draw them away from the Japanese. ... One thing may need to be watched with these ... patrols, and that is, that the Japanese have very considerable forces along the coast in the area in which they will be working. Small patrols of ours, essential for the purpose of getting information, may get away with it, but if we make a show of force at all, with say, 20 or 30 men, the enemy could very easily and quickly bring a force of several hundred or more against them. This would not only make it difficult for us to maintain observation in that area, but it could, with the superior force of the enemy, have the very effect on the natives that we want to avoid, and that is, that they would give allegiance to the stronger force.

By 13th July a memorandum was produced in MacArthur’s headquarters recommending the establishment of a base on Lake Kuvanmas in the Sepik area for the purpose of obtaining Intelligence, gaining meteorological information, favourably influencing the natives, reconnoitring for possible airfields, and protecting Intelligence parties operating in uncontrolled areas. As 500 Japanese had been reported 40 miles North-west of Lake Kuvanmas, and as the Japanese were believed to have at least 20,000 troops in the Wewak area and 5,000 in the vicinity of Hansa Bay, it was important that the position should not be discovered. If it was discovered, it could not be defended. The chances of success therefore seemed less than 50 per cent, but, as the author of the memorandum (Colonel Van S. Merle-Smith) wrote:

Even partial success over a short period will yield benefit enough. GOC, NGF and LHQ are keen to take the chance, the risk to our planes is real. However, the risk at any one time is real – I would recommend that the project be backed.

Two days later GHQ approved a plan for the establishment of a guerilla column on the Sepik. The force under the command of Major Farlow62 would be known as “Mosstroops”63 and would be flown in and supplied by air. The main task of Mosstroops would be to protect the special patrols operating in the area. At this time these patrols comprised, as well as the AIB patrol of Fryer, the FELO patrol of Stanley and the AIB-NEFIS64 patrol of Staverman, Lieutenant Barracluff’s65 patrol on the April River, Lieutenant Boisen’s66 patrol between the April River and Lake Kuvanmas and Captain J. L. Taylor’s Angau patrol near Lake Kuvanmas itself. Taylor had long been the district officer in this area, and, as mentioned, had been in a party which explored the Mount Hagen area in 1933 and had led a patrol thence to the Sepik in 1938-39.

In the month after the issue of the order by General Headquarters, 71 men were recruited in Australia for Mosstroops. An advanced party of four officers and one signaller under Captain Blood67 (“Blood Party”) was landed by Catalina at Lake Kuvanmas on 9th August; five days later Blood was informed by a local luluai that two Japanese patrols were on their way to the lake. Next day the enemy patrols approached nonchalantly, making no attempt to seek cover. They received a warm reception. “Native constables stood firm using their 303’s like veterans,” reported Blood. It was only when, after a 50 minutes’ fight, the Japanese brought up mortars and sent a third party to cut off the Australians that Blood retired to a sago swamp with weapons, ammunition and codes intact. After great hardships in very rough country the party arrived exhausted at Wabag on 23rd September.

Meanwhile, Captain McNamara68 and Sergeant Parrish,69 after being cut off from Blood’s party during the attack on Lake Kuvanmas, had hidden in a sago swamp. They decided to remain in the general area because they knew that Taylor’s and Boisen’s parties were heading for the lake. On 20th August six Japanese and a dozen armed natives attacked again but the two Australians fired on them as they fanned out, causing the natives and then the Japanese to panic and withdraw. By this action McNamara held the position until the arrival of Taylor.

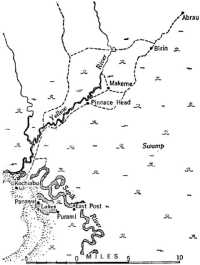

Mosstroops’ staging camps on the Sepik and Yellow Rivers

During August Farlow and a small number of his officers and men reached Mosstroops’ advanced headquarters at the junction of the Yellow and Sepik Rivers. On 5th September Farlow and Captain Grimson70 reconnoitred Lake Yimas and next day Captain Cardew71 with 5 men and 6 native constables were landed on the lake. That afternoon the enemy, with good warning from the natives, attacked this party forcing it to abandon its stores and withdraw south after inflicting 9 casualties. In his withdrawal south Cardew was entirely dependent on air droppings for supplies. The party reached Wabag on 29th October.

At one stage Farlow had plenty of worries. Not only were Blood’s, McNamara’s and Cardew’s parties missing, but nothing had been heard from Barracluff since he and Father Hansen had been left at the April River early in August when Tayfor and his party marched to Lake Kuvanmas. Boisen was therefore instructed to send out police patrols to search for him and Blood. Air reconnaissances early in September disclosed that Barracluff’s camp was intact but empty and that the launch Osprey was missing. On 10th September Squadron Leader Coventry72 who had previously found Cardew’s missing party, picked up the beginning of a radio signal “To Cov from Joe ...” which then faded out. The only “Joe” known in the area was Barracluff. Nothing was subsequently heard of Barracluff.

In spite of this unfortunate start and although the enemy was now aware that something was happening along the Sepik, it was decided to insert the balance of Mosstroops into the Sepik-Yellow River area. On 10th September Captain Milligan73 landed from a Catalina and

established a base on the Sepik but on the same day the river became swollen making Catalina landings dangerous. A temporary base was then established at Lake Panawai, and the remainder of Mosstroops and stores were flown in. By the beginning of October the movement was complete and the work of establishing a line of communication up the Yellow River and staging camps at Makeme, Birin and Abrau was begun. Advanced headquarters moved early in October from Lake Panawai to Pinnace Head.74 The Catalina unloading point for supplies was at Kochiabu just downstream from the Sepik-Yellow River junction. Thus for a few weeks after their disastrous start Mosstroops had a chance to establish themselves.

News now arrived that Staverman had been killed and the remaining members of his party would cross the mountains to the head of the Yellow River. Lieutenants Fryer and Black75 went out to find this party but returned on 23rd November having failed to do so.

On 20th October a strong party of Japanese in two pinnaces landed at East Post, forcing the five men at the base there to withdraw. Next day a group under Captain Fienberg76 arrived from Panawai and found that the enemy had gone, after having taken the wireless set and other gear. East Post was again attacked on 20th November but the Japanese were driven off with losses.

Captain McKenzie and 23 of the 2/7th Commando Squadron arrived by air on 21st November and were posted at Purami, whence they patrolled.

General Blamey was apparently convinced that Mosstroops were doing a good job because on 6th December he wrote to General MacArthur to say that New Guinea Force and Allied Air Forces were discussing the withdrawal of Mosstroops but that he was not willing to withdraw them unless ordered to do so. General Chamberlin, however, advised MacArthur that the original purpose of Mosstroops was not being accomplished, air transport requirements had been increased, and a fighter airfield was no longer required in the area. Blamey now decided that it was advisable to withdraw Mosstroops.

Japanese aircraft attacked Kochiabu on 8th December. At this stage Major Farlow was informed that maintenance by aircraft could no longer be guaranteed and on 14th December he was instructed that all parties would be removed. Between the 16th and 19th aircraft took out the whole force of 102 Europeans and 127 natives-20 plane loads.

Bena Force and Tsili Tsili Force, as well as Mosstroops and the special parties, by harassing the enemy and by letting him know that Australian troops were spread from one end of New Guinea to the other, helped to cause uncertainty in his mind and forced him to dissipate strength which he might have conserved to meet the gathering storm round Lae.