Chapter 18: Germany Turns to the Balkans

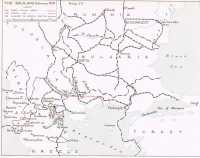

See Map 23

Map 23. The Balkans, February 1941

EARLY IN November the Greeks had successfully taken the shock of the initial Italian attacks; by the middle of the month they were striking back and quickly regained much of the lost ground. The Commander-in-Chief, General Papagos, naturally wished to exploit these successes before fresh forces from Italy—which were sure to come and indeed were already reported to be arriving—could intervene effectively. Being severely handicapped by the shortage of all kinds of transport, the Greek High Command planned first to press forward in the northern and central sectors so as to gain plenty of depth in front of the invaluable lateral road running from Koritsa to Leskovik. In the south they hoped to ease the heavy administrative burden by securing the small port of Santa Quaranta, and using it for the discharge of sea-borne supplies brought through the Gulf of Corinth. After these preliminary moves the main advance was to be made along the axis Argyrocastron-Tepelene, and was to culminate in the capture of Valona. The Italians would then have Durazzo as their only port, and the size of the forces that they could then keep in the field would be severely limited.

By the second week in December the Greeks had reached Pogradetz at the southern point of Lake Okhrida, and had penetrated deep into the mountains to the north-west of Koritsa; their northern flank was thus secure. In the centre they had made good progress in the direction of Berat, and in the south they had captured Santa Quaranta and Argyrocastron. The next step was to secure the important road-centres of Klissoura and Tepelene. By 10th January Klissoura had been captured but Tepelene was still in Italian hands. On the rest of the front it had been necessary to call a halt while communications were improved and the supply and transport organizations overhauled. Some sharp counter-attacks were made at various points by the Italians, but they were repulsed without great difficulty.

Although they were held up at Tepelene, the Greeks had every reason to be proud of their achievements. General Papagos had felt able to transfer troops from opposite the Bulgarian frontier, and by the end of the year had succeeded in making about thirteen divisions

available for the Albanian front. Meanwhile the Greeks had identified elements of some fifteen Italian divisions in the fighting. The Italians had the advantage of having been on a war footing for much longer than the Greeks, but when it came to fighting in the mountains they felt an acute lack of infantry, their divisions having been reduced from three infantry regiments to two.1 Against this, the Greeks had not the vehicles and mobile equipment with which to exploit the successes that they gained in the mountain fighting. Their lack of tanks and anti-tank weapons compelled them to keep away from the more open ground, so that their progress was slow and the strain on men and pack animals was very great.

During December, January, and the early part of February Air Vice-Marshal D’Albiac’s three bomber squadrons were directed almost entirely against ports, airfields and points on the Italian lines of communication, principally Valona, Durazzo, Berat and Elbasan. The weather could hardly have been worse; the heavy falls of snow, the prevalence of low cloud, and the severe icing conditions made flying difficult and hazardous. Based, as the bombers were, on airfields near Athens, every raid into Albania meant a preliminary flight of some 200 miles to the frontier, and later 200 miles back, over mainly mountainous country which made the navigational aids unreliable and added to the strain on the aircrews. In order to keep down the losses from the enemy fighters that were being encountered, over the targets in increasing numbers, it was necessary to provide escorts for the bombers.2 This was not easy to do, on account of the distance between the bomber and fighter airfields, the unreliable communications, and the constant changes of weather. Moreover, the squadrons were falling below strength and were handicapped by the shortage of spares, of ground equipment, and of transport. The salvage of any aircraft larger than a fighter along the narrow winding roads was almost impossible. All this tended to reduce the effectiveness of the small bomber force, and the determination of the pilots and aircrews to carry out their arduous tasks in spite of all difficulties deserves the highest praise.

Throughout January it became increasingly probable that the Germans intended to enter Bulgaria with a view to attacking the Greeks, who would then be faced with a war on two fronts. If this happened, the Greek situation would indeed be desperate. As it was, they had a great many difficulties to contend with on the Albanian front alone. Their battle casualties had not been excessive, in view of what they had achieved, but the weather was causing great hardship. Blizzards had been frequent, and large numbers of men were disabled by frostbite. Clothing and boots were woefully scarce,

and so were vehicles and pack animals. And unless something drastic was done there would be no gun ammunition left in two months’ time.

The three ships of convoy ‘Excess’, whose eventful passage was described in the last chapter, had brought a welcome contribution of vehicles and stores of all kinds, and some field and anti-aircraft guns and ammunition. But the whole problem of arranging for the supply of war materials to Greece was very complicated. The Greeks had started the war with a large variety of weapons mainly of French and German make. In England there was no ammunition for these types; in the United States of America the small remaining stocks of French ammunition had either been delivered to Greece or were on their way. Further orders on the United States of America would affect the British armaments programme and in any case could not be met in time for Greece to receive supplies before the end of 1941. The only satisfactory solution would be to re-equip the Greek forces with British weapons. This, however, would take a long time because there were no reserve stocks; it would also seriously delay the equipping of our own troops. All that could be done immediately was to try to meet the essential needs of the Greek arsenal and supply the Greek forces with as much as possible of the Italian equipment and transport captured in Libya.

One effect of the Albanian war had been to add very greatly to the amount of shipping requiring escort in the Eastern Mediterranean and Aegean. During December and January seven convoys, of 63 ships in all, carried supplies to Greece from Alexandria and Port Said without loss. One of these convoys was escorted by Greek destroyers, as were several smaller convoys to Piraeus from Suda Bay and the Aegean ports.

Greek submarines had had some successes against the Italian supply line across the Adriatic, and had sunk a 12,000 ton transport and (according to the Italians) one other merchant vessel, but the lack of maintenance facilities caused this effort to fade out. Meanwhile continuous patrols of the Elaphonisos and Kithera Channels—north and south of the island of Kithera respectively—were maintained by British minesweeping corvettes and trawlers, sometimes supported by cruisers and destroyers. On February 3rd Greek patrol boats took over the Elaphonisos Channel, and two days later the enemy’s mining at Tobruk made it necessary for the British to relinquish responsibility for the Kithera Channel also. By this date no anti-torpedo baffle was in place at Suda Bay, so that, although this anchorage could be used as a base for operations by destroyers and light craft, cruisers and bigger ships could use it only as a quick fuelling base. The airfield at Maleme was taken into use by fighters of the Fleet Air Arm towards the end of January.

In view of the growing likelihood during January that troops would have to be moved back to the Bulgarian frontier, General Papagos decided to resume the offensive as soon as possible in a determined attempt to take Valona. A great deal depended upon the outcome of this operation, and the greatest single obstacle to a Greek success was deemed to be the supremacy of the Italian Air Force. The Greek Air Force had virtually ceased to exist and the Italian Air Force held undisputed mastery over the forward areas, where their continual air attacks had begun to tell on the morale of the Greek troops. Moreover the weight of the air attacks on the enemy’s rearward organizations was, in the circumstances, so small that it could hardly have interfered seriously with the flow of Italian reinforcements. The Greek High Command therefore appealed at this moment for more air reinforcements, and urged the Air Officer Commanding to change his bombing policy and use his squadrons in close support of the Greek troops. The success of the whole operation might depend upon the stimulus afforded by the sight of friendly aircraft overhead and by the satisfaction of seeing the Italians receive the punishment that the Greeks had endured for so long. Air Vice-Marshal D’Albiac recognized the force of these arguments and acceded to General Papagos’ request. Sir Arthur Longmore afterwards wrote, ‘There is no doubt that this departure from the orthodox was a great stimulant to morale’,3 and the Greeks were generous in their praise of the willingness of the Royal Air Force to take great risks in order to give as much encouragement as possible to the troops.

Further help was forthcoming from the Middle East Command. Six Wellingtons of No. 37 Squadron left Egypt for Greece on February 12th, and on the same night, making a special effort, they successfully attacked the airfields at Durazzo and Tirana. No. 33 Squadron (Hurricane) was also ordered to Greece; their ground crews sailed on the 15th, and the aircraft followed a few days later. For the better control of the air operations a Wing Headquarters was now formed at Yannina. All serviceable Blenheim I aircraft were moved forward to the landing strip at Paramythia, which was dry enough to take them, but which had to be provisioned by air for some days until communication by road could be established. A second fighter squadron was also sent forward, together with a few Hurricanes which had just arrived for the rearming of No. 80 Squadron. By the end of February the Wing had provided nearly 200 sorties in support of the Greek army. Since the Greek campaign began the Royal Air Force had lost 30 aircraft and the Italians 58.

To the great disappointment of the Greeks the weather became very bad soon after they had begun their attack on 13th February to

capture Tepelene, and although they met with some success at first the operation had to be suspended. By this time it had become evident that a big Italian offensive against the central sector was being prepared. It was not destined to succeed, but it marked the end of the Greek hopes of capturing Valona.

As might be expected, the complete failure of the Italian plans for the rapid occupation of Greece caused much recrimination in political and military circles in Rome. It was obvious to everybody that not enough forces had been assigned to the task; in von Rintelen’s view the arrangements were suitable only for a military entry without any fighting, while the logistic organization was rudimentary and from the outset quite unequal to the strain. Marshal Badoglio was in the not entirely enviable position of being able to remind the Duce that the General Staff had estimated twenty divisions as the size of the force required. This he duly did, and on November 26th resigned his post as Chief of Staff. His place was taken by General Cavallero, an officer with a reputation for organizing ability. General Visconti Prasca had already been replaced in command of the Albanian front by General Soddu, the former Under-Secretary of State for War, but in December Soddu was removed in turn and Cavallero himself went to Albania. As if this was not enough for the bewildered Italian public, Admiral Cavagnari, the Chief of the Naval Staff; was replaced by Admiral Riccardi.

Having thus pinned the blame on his professional advisers Mussolini made great efforts to restore the Italian fortunes. Graziani and his troubles were forgotten, and the Albanian front assumed overriding importance. Mussolini announced to Hitler in a letter of 22nd November that no less than thirty divisions were being made ready for Albania. (By the middle of March 1941 a total of twenty-eight had indeed been sent there.) Hitler had been following the progress of events with some attention, and by 9th December a German Air Transport Group—the first unit of the Luftwaffe to be stationed in Italy—had begun to work between Foggia and Albania. Early in January he decided that further action on his own part was called for, and directed that a strong German contingent was to be put under orders for Albania. (Operation Alpenveilchen.) The Italians were not enthusiastic about this offer and succeeded in getting the proposed force whittled down to one mountain division, by stressing the difficulty of supplying a German force along the already overloaded line of communication. By the middle of February it seemed to the Germans that the Italians—with twenty-one divisions—were now capable of holding their own and were unlikely to lose Valona. As the German General Staff had come to the conclusion that no decisive success could be achieved in Albania at that time of year, even by German troops, the proposal to send the mountain division

was dropped and the Italians were left to themselves to pin down as many Greek and British forces as they could.

By the first week in January the prospects in Libya and Albania were distinctly encouraging. On both fronts the Italians had suffered serious reverses, while their irresolute defence of Bardia had confirmed the impression, gained during the fighting in December, that there were many Italians whose hearts were not in the war. It was at this moment that Germany’s intention of going to the help of her failing ally became apparent. Information was reaching London which showed that the Germans were busily making preparations in Rumania with the ultimate purpose of attacking Greece. There was little doubt that the move would be made through Bulgaria, where the Government appeared to have lost control of events and where the Press had become little more than a mouthpiece of Axis propaganda. Would Greece stand firm under this added threat? ‘. . . Although perhaps by luck and daring’, wrote the Prime Minister to the Chiefs of Staff on January 6th, ‘we may collect comparatively easily most delectable prizes on the Libyan shore, the massive importance of the taking of Valona and keeping the Greek front in being must weigh hourly with us’.

These anxieties were reflected in the instructions sent to the Commanders-in-Chief by the Chiefs of Staff on January 10th, a week after the capture of Bardia. The German advance into Bulgaria might be expected to begin in perhaps ten days time, and would probably be directed upon Salonika through the Struma valley. One armoured and two motorized divisions and parachute troops, supported by some 200 dive-bombers might be used; three or four more divisions might be added after March. The easterly route from Bucharest to Dedeagatch would probably not be used, being too near to the Turkish frontier; nor was an advance through Yugoslavia thought to be likely. Bulgaria was not expected to offer any resistance. In these circumstances His Majesty’s Government had decided that it was essential to afford the Greeks all possible help, in order to ensure that they would resist German demands by force. The extent and effectiveness of our help might well determine the attitude of Turkey, and it would have an influence upon opinion in the United States of America and Russia.

As soon as Tobruk had been captured, assistance to Greece was to take priority over all operations in the Middle East, though this decision was not to be taken as forbidding an advance to Benghazi ‘if the going is good’. But the Commanders-in-Chief were told once again that any immediate help provided must come from their resources. Wavell and Longmore were to go and confer with General

Metaxas in order to exchange views and to determine the size of force to be sent. The Chiefs of Staff in London were obviously not in a position to lay this down, but they expressed the view that assistance would have to take the form of furnishing specialist and mechanized units and air forces with which to support the Greek divisions. They specified various types of tank and artillery units that might be sent, in addition to three Hurricane and two Blenheim IV squadrons.

Before this decision on policy reached the Commanders-in-Chief, they had a good idea of what was in the wind from an Air Ministry telegram, warning Longmore of the scale of air assistance to Greece that was being contemplated. He pointed out that this would mean, in effect, the transfer of perhaps all three of his Hurricane squadrons from Libya; that even if they were sent there were no airfields large enough for them in the Salonika area, and none at present available within reach of the Italians, in Albania; that his only two Blenheim IV squadrons—other than those on convoy escort along the Red Sea route—were supporting the advance of the Army in Libya. To withdraw these bombers and fighters would not only severely handicap all the Libyan operations, but would give the Italian Air Force time to reorganize and be reinforced from Italy. General Wavell’s reaction was to urge the Chiefs of Staff to consider most earnestly whether the German concentration in Rumania was not a bluff to induce us to disperse our force in the Middle East, to stop our advance in Libya when it was going so well, and to play upon the Greek morale. On the other hand, if the reports were accurate and if a determined German advance was about to begin, nothing that we could send from Egypt would arrive in time to stop it.

Although these expressions of doubt crossed, in transmission, the Chiefs of Staff’s instructions, they drew from the Prime Minister an immediate rejoinder, amplifying the reasons for. the Government’s decision. The German concentration in Rumania was certainly no bluff, nor was it a move in the war of nerves. The force might not be large but it would be of deadly quality. If not stopped it might play the same part in. Greece as the breakthrough of the German Army on the Meuse played in France. All the Greek, divisions in Albania would be fatally affected. The destruction of Greece would eclipse the victories gained in Libya and might affect the Turkish attitude decisively, especially if we had shown ourselves callous of the fate of an ally. Large interests were therefore at stake. The matter had been earnestly weighed by the Defence Committee of the Cabinet. ‘We expect and require prompt and active compliance with our decisions for which we bear full responsibility.’

By this time General Wavell had already made his arrangements to go to Athens and was preparing to send to Greece such units as

could be made immediately available. He had learnt from Major-General T. G. G. Heywood, the Army member of the military mission, that the Greeks would be unlikely to ask for field or medium artillery for the Albanian front, but would probably want transport and antiaircraft artillery. These were two of his own worst shortages: the former was wanted everywhere, and in particular for maintaining the momentum of the advance in Libya; the latter was already stretched to the utmost, and any despatches to Greece would be at the expense of the naval and air bases and the troops in the forward areas. The appearance of the Luftwaffe within the last few days increased the need for strengthening the anti-aircraft defences; it was certainly an inopportune moment for weakening them.

General Wavell left for Athens on 13th January. Air Chief Marshal Longmore was visiting his units in Libya at the time, and followed two days later. Meetings took place with the President of the Council, General Metaxas, the Commander-in-Chief; General Papagos, and their staffs. Admiral Cunningham was represented by the British Naval Attaché, Rear-Admiral C. E. Turk.

As regards the Albanian front General Papagos explained that his worst shortages were of transport, clothing, and anti-tank and antiaircraft artillery. General Wavell at once decided to divert, to Greece a shipload of transport vehicles which had just reached Egypt, and to follow this up with as many captured Italian lorries as possible as soon as they could be got back to Alexandria and shipped. He had very few pack animals and none to spare. He had already sent 180,000 pairs of boots, 350,000 pairs of socks, large numbers of blankets and much clothing from his reserve stocks. He mentioned his own acute shortage of anti-aircraft artillery, but having understood that the Greek advance in Albania was being much hampered by low-flying attacks, he offered to send a combined anti-aircraft and anti-tank regiment for use on that front. This was politely but quite definitely refused as was the offer of a company of light tanks, on the ground that it would be too difficult to maintain them.

As for the provision of further air support, Air Chief Marshal Longmore could make no definite promises, in view of his many commitments, but asked that the work on the airfields in the area south and west of Mount Olympus should be pressed on with all speed in order that fourteen squadrons could be handled. The provision of these, in a serviceable state, would be the limiting factor in sending squadrons from Egypt. His considered opinion was that two fighter squadrons and one Blenheim squadron were the most that could be accommodated in Greece at present, in addition to the four squadrons already there, and they would be sent at once.

Discussion on the German preparations in Rumania showed that the Greeks did not regard an advance to be immediately practicable,

on account of the bad state of the roads and the lack of bridges. This did not mean that they questioned the facts; indeed, they estimated six German divisions, including one armoured division, to be in southern Rumania. Bulgaria had four divisions on the Greek frontier and, five opposite Turkey, and could mobilize nine more. General Papagos explained that the concentration of the Greek forces against the Italians had left only about four weak divisions on the Bulgarian front. He estimated that for the defence of Eastern Macedonia and Salonika a further nine divisions with appropriate air forces would be needed.

A wide divergence was now apparent between the British and Greek views. The army units offered by General Wavell amounted to two regiments of field artillery, and one or two of medium artillery; one anti-tank regiment; one cruiser tank regiment; and one or two batteries of anti-aircraft artillery. General Metaxas considered that the arrival of such a force would have none of the desired results. It was likely to provoke an attack by the Germans, and possibly by the Bulgarians also, which the British and Greeks would not be strong enough to check. The effect on Yugoslavia would be very different from what the British expected: he had a categorical assurance that Yugoslavia was resolved to oppose the passage of German troops through her territory, but that this assurance would be withdrawn if the German aggression were provoked by the presence of British forces in Salonika.

The most important step, in the President’s opinion, was to clear up the situation in Albania; this would release large Greek forces for the Bulgarian front. As soon as these were available he would welcome British assistance. The best plan therefore was to make all possible secret preparations for landing a British expedition at Salonika and the neighbouring ports, but to send no troops at all until they could arrive in sufficient numbers to act offensively as well as defensively. General Metaxas therefore proposed that a joint study should be made by the staffs; the Greeks themselves would then make the necessary preparations. The move of British troops to Greece should take place only if German troops crossed the Danube (or the frontier of Dobrudja) and penetrated into Bulgaria. General Wavell, loyally supporting his instructions, maintained the British view ‘with all the arguments I could command’, but without success. The President added that this should not be interpreted as a final refusal, but as a request for postponement. Finally, and with great emphasis, he said that if Salonika were attacked the Greeks would fight to the last; the British could rest assured that the Greeks would be with them to the end whether Germany came in or not; there would be no question of a separate peace.

The refusal to accept the immediate offer of British Army units

applied also, as far as the Salonika area was concerned, to units of the Royal Air Force. General Metaxas agreed, however, that this area should be used for the re-forming of the Greek Air Force. Air Chief Marshal Longmore welcomed this decision, as it offered an opportunity of developing the appropriate airfields; these would be available in emergency as advanced landing grounds and refuelling bases. Permission was given for officers of the British Air Mission to visit them, and also to reconnoitre airfields on the islands of Lemnos and Mitylene. Longmore had already been told that aircraft for the reconstituted Greek Air Force would come out of his own reinforcements, and some 30 of the first Mohawk fighters to arrive had been promised to Greece. Unfortunately, a defect had been found in the engines of these aircraft, which made a major modification necessary, so that further delays would occur before they could reach the Middle East. He was now told that 500 Tomahawk fighters had also been purchased from the United States of America and that 300 of these would reach Takoradi during the next five months. Little was known of their operational characteristics; but as they were fitted with American guns they would be useless until supplies of American ammunition could also reach the Middle East. As it was not known when this would happen, it was impossible for the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief to make a firm plan for rearming his own squadrons or those of the South African or Greek Air Forces. He could only urge the Air Ministry to keep up the supply of Hurricanes at the highest possible rate because the question of the supply of American aircraft had not yet been clarified.

On hearing the result of the discussions the Chiefs of Staff replied that the Defence Committee had noted the Greek Government’s refusal of British units for the Albanian front and that there could be no question of forcing our aid upon them. As regards Salonika it was assumed that General Metaxas was fully aware of the information which had prompted His Majesty’s Government to make their offer; if so, we must submit to his judgment. But Wavell and Longmore were instructed before leaving Athens to make it quite clear that, if the special force proposed by the British was not despatched until after the German advance had begun, it would certainly be too late. For their own information the Commanders-in-Chief were told that there could be no question of sending to Salonika, either now or later, an expedition strong enough to act offensively as well as defensively. It was even possible that British forces might have to be sent to Turkey instead of to Greece. Therefore no preparations for the reception of British troops at Salonika and neighbouring ports were to be made except for those units needed for the maintenance of any air squadrons operating from that area.

General Wavell arrived back in Cairo on the evening of the 17th, having visited Crete and having had a discussion with Admiral Cunningham at Alexandria on the way. He immediately cabled his own views on what had occurred. He thought that the British proposal was a dangerous half-measure. The help suggested would not be enough to give the weak Greek forces at present holding the Bulgarian front the support they would need if the Germans were really determined to capture Salonika. Almost inevitably we should be compelled to send further troops in haste or become involved in retreat or defeat. If valuable technical troops were now sent to Salonika and Germany made no move, they would be locked up to no purpose. Meanwhile, the advance into Libya would come to a halt and the Italians would be given time to recover. Both from the naval and air points of view there would be great advantages in securing Benghazi, but air protection during the advance and afterwards would be essential, and he regarded the shortage of fighter aircraft and anti-aircraft equipment as the most serious factor in the present situation. The result of dispersing resources still farther—to cover Salonika, for instance—would be weakness everywhere, with no port, base, or other vulnerable point properly defended. The arrival of the German Air Force in the Mediterranean increased the gravity of this matter. General Wavell added that he thought Germany might well hesitate to violate Bulgarian neutrality, because this would expose the Rumanian oilfields to air attack. Finally, he was of course ready to send the strongest force available if the War Cabinet ordered him to do so, but he felt it his duty to communicate the foregoing views and to state his conclusions : that the Greek refusal should be accepted; that reconnaissances and preparations of the Salonika front should go ahead; but that no promise should be given to send troops at any future date.

On 21st January the Commanders-in-Chief received the British Government’s conclusions reached in the light of the Greek refusal and of the appearance of the Luftwaffe in the Central Mediterranean. First, the capture of Benghazi was clearly of the greatest importance. It ought to become a strongly defended naval and air base, and its use should enable the long overland line of communication to be dropped, with a great saving of men and transport. Secondly, the German Air Force must be expected to spread into the Dodecanese Islands and threaten Alexandria, the Canal, and the sea communications with Turkey and Greece. It was therefore important to capture these islands, particularly Rhodes, as soon as possible. The troops for this expedition would have to be found from Middle East resources, to which would soon be added the Special Service troops

about to sail in the Glen ships.4 Thirdly, it was confirmed that No. 11 (Blenheim) Squadron and No. 112 (Gladiator) Squadron were to go to Greece. The Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief was now to regard as his first duty the maintenance at Malta of ‘a sufficient air force to sustain its defence’, and to help in this HMS Furious was shortly to take a third consignment of Hurricanes to Takoradi. Finally, a strategic reserve should be created, with the primary object of rendering assistance to Turkey and Greece within the next two months. It was hoped that this force would soon attain the equivalent of four divisions. The arrival of these instructions from the Chiefs of Staff coincided with the welcome news of the capture of Tobruk.

Having been asked for their comments, the three Commanders-in-Chief replied agreeing that the capture of Benghazi and Rhodes was of urgent importance and ‘noting’ the need for forming a strategic reserve. They thought that the reinforcements and equipment which General Wavell was expecting to receive would go some way towards enabling the Army to carry out its various tasks, but the sort of risks which the Navy and Air Force had been taking with weak forces against an unenterprising enemy would not be justified against the Germans. It was fully intended to push on to Benghazi, but the subsequent development and defence of this port would be governed primarily by the arrival of equipment from England. More supply ships would be essential; in the meantime, by using men-o’-war and by continuing to run light craft long after they were due for a refit, a limited supply line by sea could be kept going, but only as far as Tobruk; so that the need for a land route would not disappear. The Navy had not enough light craft and escort vessels to safeguard a sea supply line stretching as far as from John-o’-Groat’s to Land’s End, and at the same time cover the convoys to Malta and the increasing traffic in the Aegean—not to mention any other operations. As it was, traffic between Cyprus, Palestine, and Egypt had to run unescorted. Admiral Cunningham required, first, a flotilla of destroyers and two modern cruisers with good antiaircraft armament; next, a number of small merchant ships of about 2,000–3,000 tons and a speed of at least ten knots. These were not to be found in the Mediterranean; he had already been compelled to take three ships off the feeder service to Greece and Turkey in order to run a supply service even to Sollum.

The capture of Rhodes was obviously an urgent requirement and would be done as soon as possible after the arrival of the Glen ships. If the Luftwaffe began to operate from the Dodecanese the whole coast from Haifa in Palestine to Apollonia in Cyrenaica would be within range of German bombers. Even if Benghazi were in our

hands, the air threat to Egypt would remain until Rhodes had been taken, so that fighters would have to be kept in Egypt for the present for the defence of the naval base and the Canal. There seemed, to be no signs of the men and equipment for the three fighter squadrons which the Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief had been authorized to raise. As regards Malta, the Air Chief Marshal pointed out that it was not easy to fly fighters to the island even from Libyan airfields at this time of year.

To these comments the Chiefs of Staff replied that Admiral Cunningham’s naval requirements would be met during the next three months; the necessary merchant ships would be collected from other areas as soon as possible. Once again they stressed the need for abolishing the overland line of communication in Cyrenaica; when Benghazi became a well-filled base with substantial reserves of supplies there would be no need for coastal convoys to run continuously. They hoped that the coastal and anti-aircraft defences of the port would be largely provided by captured Italian guns and equipment. As regards the Dodecanese, the Glen ships would arrive early in March and it was hoped that the first major operation would be undertaken by the middle of March at the latest.55 Finally, Sir Arthur Longmore was given authority to form as many new squadrons as his resources permitted; a concession which, in the circumstances, he could not regard as very helpful. In short, the impression left upon the Commanders-in-Chief was that they would have to live for some time largely upon what General Wavell called their ‘leanness’.

Towards the end of January the Chiefs of Staff became convinced that preparations were being made for a German move into Bulgaria, and His Majesty’s Government turned its attention to the increasing danger threatening Turkey. At the staff talks the Turks had accepted the idea of a single Allied front in the Balkans.6 They realized that Greece had first claim to British aid both in men and materials, but if their own country were attacked they would certainly want, above everything else, aircraft—especially fighters—and anti-aircraft artillery. They were dissatisfied at the inability of the British to work to a firm programme, even for the supply of aircraft which had long been on order for the Turkish Air Force. Many of their squadrons were therefore grounded, and training was being delayed. They had promised to hasten the preparation of ports, airfields and communications to which the British attached so much importance, but they naturally hesitated to do anything which might plunge them into war against the Axis before their own formations were suitably

trained and equipped. The report of the staff talks reached London on 22nd January, and on the 31st the Prime Minister addressed a personal appeal to the President of the Turkish Republic.

He pointed out that the Bulgarian Government were allowing the Germans to establish themselves on Bulgarian airfields, and drew attention to the consequent grave danger to Turkey. The remedy was to adopt similar measures. The British Government would send to Turkey at least ten squadrons of fighters and bombers apart from those now in action in Greece, as soon as they could be received. They were also prepared to send 100 anti-aircraft guns from Egypt. More air forces would follow. Together we should be able to threaten to bombard the Rumanian oilfields if the Germans were to advance into Bulgaria. At the same time the threat to Baku might well restrain Russia from giving any help to the Germans.7

This message caused the Chiefs of Staff to change the emphasis in their recent instructions to the Commanders-in-Chief. The ‘Graeco-Turkish situation’ was now to have first place in their thoughts, and steps to counter German infiltration into Bulgaria were to be given the highest priority. Benghazi was to be captured as quickly as possible, provided this could be done without prejudice to the European interests. Action against the Dodecanese was more urgent than ever because of the need for good communications with Turkey. Air Chief Marshal Longmore was warned that if the Turkish Government accepted the Prime Minister’s proposals the ten squadrons referred to were to be found by him. He expressed astonishment that squadrons should be sent to Turkey, where they might be locked up doing nothing, at a time when operations against the Italians in Cyrenaica and Eritrea were in full swing and there was an urgent need to oppose the Luftwaffe in the Mediterranean. The reply was that they must try to deter Germany from absorbing in turn Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, thus dominating the Eastern as well as the Central Mediterranean. When he restated his many shortages and pointed out that his replacements of aircraft were barely keeping pace with current wastage, he was told that by the end of March he might expect to have received a further 100 Hurricanes, 120 Blenheim IVs, 45 Glenn Martins and 35 Wellingtons, so that by careful planning and by taking risks—particularly against the Italians—it might be possible to meet all his commitments. It was admitted, however, that the Air Force would be stretched to the utmost.

The Prime Minister’s message was not, however, received with much enthusiasm by the Turkish President. The presence of British army and air units in Turkey would inevitably mean the entry of Turkey into the war, which, in the opinion of the President, would

not be in the best interests of either Britain or Turkey. Turkey was still very short of military equipment and supplies, and until her state of preparedness was much improved she was not prepared to take any action likely to provoke the Germans.

Meanwhile, the Greeks had suffered a grievous loss in the sudden death, on January 29th, of General John Metaxas, whose resolute leadership had been an inspiration to the whole nation. It can never be easy to succeed a dictator, and there were obvious difficulties in store for the new President, M. Alexander Koryzis, Governor of the National Bank of Greece and former Minister of Public Assistance. On February 8th—two days after the British had entered Benghazi—M. Koryzis reaffirmed the determination of Greece to resist a German attack at all costs, and repeated the declaration made by General Metaxas that no British troops were to be sent to Macedonia unless the Germans crossed the Rumanian frontier into Bulgaria. Staff talks had been taking place during the past three weeks to investigate the possible composition of a British force to be sent in that event, and M. Koryzis now suggested that this matter should be settled, in order to determine whether the British and Greek forces together would be sufficient to check the German attack and encourage Yugoslavia and Turkey to take part in the struggle. He added his conviction that the premature despatch of an insufficient force would be treated by the Germans as a provocation; it would destroy even the faint hope that the attack might be avoided.

The programme outlined by Hitler in his letter to Mussolini of November 20th could not, in the event, be carried out in full.8 Mention has already been made of General Franco’s refusal to receive German troops in Spain early in January 1941. Bulgaria was invited to follow the example of Hungary and Rumania by adhering to the Tripartite Pact between Germany, Italy, and Japan, but declined to be hurried, principally because she was nervous of Russia and Turkey. But although she was unwilling to side openly with Germany, she promised to give secret support for the German preparations for an attack upon Greece; when the time came she would offer no resistance to the passage of German troops through her territory but she would make no promise of active support.

By about the end of the year the results of Germany’s further diplomatic activities were broadly as follows. She could not be certain that Yugoslavia would stand aside while Greece was attacked, but had to assume that the passage of German troops through Yugoslavia would not be permitted. Action by Turkey against Bulgaria was unlikely, but would have to be guarded against; the

Bulgarians would therefore have to mobilize in time to protect themselves. The attempts to divert Russia’s attention from the Balkans had been singularly unsuccessful; she had continued to watch German activities very closely and had even made a cautious attempt to influence Bulgaria herself. When the Russians enquired the meaning of the German concentration in Rumania and the preparations for moving into Bulgaria, they were told that the British were to be driven out of Greece but that the Germans had no intention of violating Turkish neutrality unless Turkey herself intervened.

The main German forces began to move into Rumania through Hungary early in January, the, arrangements for their reception having been made by the strong Army and Air Missions ostensibly set up to organize and train the Rumanian forces. The directive for operation ‘Marita’ was issued by Hitler on 13th December, in confirmation of plans already well advanced. The object was to move through Bulgaria and occupy Grecian Macedonia, and possibly the whole mainland of Greece as well, in order to prevent the British from establishing under the protection of a Balkan front an air base which would be a threat to Italy and to the Rumanian oilfields. The forces allotted were the 12th Army, then in Vienna under Field-Marshal List, supported by Fliegerkorps VIII, under General Frh. von Richthofen. Field-Marshal List was to have five army corps headquarters; one group of four armoured divisions; and one motorized, two mountain, and eleven other divisions. Fliegerkorps VIII would consist of 153 bombers (39 Ju 88, 114 Ju 87) and 121 fighters (83 Me 109, 38 Me 110). There would be a liberal allotment of anti-aircraft (flak) units.

The 12th Army was told to be ready to start moving into Bulgaria any time after 7th February, but the severity of the weather made it impossible to keep to the programme of train moves, and the preparations for crossing the Danube were held up by the treacherous ice. On 6th February the date was postponed a fortnight. Meanwhile the bad weather had interfered with the moves of the air forces, and a thaw in the middle of February made most of the Rumanian airfields unusable. On the 17th Hitler ordered a further postponement: the bridging of the Danube was to start on February 28th, and the first crossing on March 2nd. The attack on Greece was to be made in the first few days of April.

Thus the information which led His Majesty’s Government to offer help first to Greece and then to Turkey was timely and accurate. In the circumstances this is not surprising, for Hitler could only allay the suspicions of Russia, Turkey, and Yugoslavia, by creating the impression that Germany’s intervention in the Balkans was directed only against Britain and her ally, Greece. The time factor

was of great importance to him, for there seemed no likelihood of the Italians being able to clear up the Greek situation unaided, and he particularly did not wish German military intervention to drag on in such a way as to interfere with the preparations for the attack on Russia. For it was this attack—‘Barbarossa’—that really mattered; everything else was subsidiary and he had laid down in his Directive of 18th December that preparations for ‘Barbarossa’ must be completed by 15th May. In deciding that there would be time to carry out ‘Marita’ first, Hitler was staking heavily on the correctness of his political judgment. For if Turkey should turn hostile in consequence of German military activity so near her frontier, the German General Staff estimated that ‘Barbarossa’ could not begin on the intended date. Nor would it be wise to begin ‘Marita’ unless Yugoslavia, whose frontier lay so close to the approaches to Salonika, could be relied upon to remain passive. The risk was accepted, however; but on the day of the Yugoslav coup d’état, 27th March 1941, Hitler postponed ‘Barbarossa’ about four weeks.

Blank page