Chapter 11: The Battle of Gazala (contd.): The Loss of Tobruk

ON 15th June General Rommel informed Comando Supremo that the enemy was probably withdrawing the bulk of his forces beyond the Egyptian frontier. Cavallero at once signalled to Bastico that the tactical success must be exploited and that a stalemate must be avoided, for the Axis forces could not undertake a long siege of Tobruk. Air forces would have to be withdrawn from North Africa at the end of June to assist in the capture of Malta, which was as necessary as ever; indeed Rommel’s urgent request for 8,000 men could not be met because Hitler had placed a ban on the movements of German troops by sea until the situation round Malta had been cleared up. General Rommel, for his part, required no prodding. Baulked in his attempt to cut off all the troops retiring from Gazala he lost no time in setting his forces in motion eastwards. The 21st Panzer Division was directed on El Duda, and the 90th Light was ordered (for the third time in a week) to advance on El Adem.

Before describing the outcome of these orders it will be convenient to consider briefly how the 8th Army was trying to cope with the situation. General Ritchie had not yet had the Commander-in-Chief’s approval for allowing Tobruk to be isolated (this was not given until 16th June) and could say no more than that Tobruk was to be a bastion upon which mobile operations could be based and that the 13th Corps was to deny it to the enemy. The 30th Corps would be responsible for the operations outside the perimeter, for which purpose General Norrie would have under his command the 7th Armoured Division, the 29th Indian Infantry Brigade at El Adem, and the 20th Indian Infantry Brigade at Belhamed. At the same time he was to complete the occupation of the positions on the frontier and organize a striking force with which to resume the offensive. The immediate problem was to strengthen the 7th Armoured Division, on which would largely depend any chance there might be of preventing the enemy from lapping round the southern flank of the 13th Corps. The only mobile formations available were the battered but resilient 4th Armoured Brigade and the 3rd Indian Motor Brigade. The flow of repaired tanks from the forward workshops was expected to be 15 to 25 a day, and about 9 a day were coming forward from Egypt; at this

rate it would be several days before the 2nd and 22nd Armoured Brigades could be re-equipped. In these straits General Ritchie’s reflections led him to turn to the idea of ‘Jock’ columns.

Since the very beginning of the war in the Western Desert these columns had been such a feature of the British mode of warfare that they deserve a word to put them into perspective. There is no doubt that they were a stimulating form of enterprise which at times caused the enemy anxiety and loss. Brigadier ‘Jock’ Campbell himself knew well their limitations, and in April 1942 General Auchinleck saw fit to lay down a policy for their use. Columns, he wrote, could harass or could carry out a pursuit against weak rearguards, but they could not drive home an attack against other than very weak resistance nor deny ground except for a very short time. He considered that their use tended to disperse resources (especially artillery) and to make the troops so accustomed to tip-and-run tactics that they might begin to regard all-out attack or protracted defence as exceptions rather than the rule. He therefore directed that columns should be sparingly used, and gave as examples of suitable tasks: raids on definite objectives; harassing, covering, and delaying operations ahead of a defensive position on a definite plan; support of armoured cars on reconnaissance; and, in certain circumstances, pursuit.

General Ritchie now felt that the column could help him in his predicament. He considered the enemy’s tanks to be superior to his own, and that therefore the offensive weapon must be the field gun. On 16th June he issued instructions for infantry divisions to split into two, with an advanced mobile element of regimental groups (or columns) of all arms and a rear or static clement occupying a sector of the frontier defences. A regimental column was to consist of the headquarters of a battalion or field regiment, a field battery, an anti-tank battery, an anti-aircraft troop, and a battalion of infantry (less one company) to provide local protection for the guns. But field guns were none too plentiful at this moment, and the arrival of the 1st South African and 50th Divisions in the frontier area was eagerly awaited. Not until 17th June was it known with any certainty what was their state of completeness. Meanwhile the Commander-in-Chief’s attention was firmly fixed on El Adem, and he constantly urged the Army Commander to reinforce it, which was just what General Ritchie could not do.

Two battalions of the 29th Indian Infantry Brigade (Brigadier D. W. Reid) held the locality of El Adem, with the third battalion—the 3rd Royal Battalion 12th Frontier Force Regiment—holding a detached position to the north-west at B 650. On 15th June the 90th Light Division made three attacks on El Adem and was beaten off. During the afternoon an attack by the 21st Panzer Division on B 650 was also beaten off and the 7th Motor Brigade was credited with very

effective co-operation. At 7.30 p.m. General Norrie spoke confidently to the Army Commander. He felt that El Adem would hold fast, but he did not then know that the 21st Panzer Division had just driven home an attack which overran and captured B 650 and its garrison. Next morning Norrie spoke very differently. He felt that his mobile troops were too few to guarantee support to the garrisons of El Adem and Belhamed for the next few days, and that without this support they could not be expected to hold out for long. He did not feel that the casualties which a last-ditch resistance would inflict on the enemy would compensate for the loss of these brigades. The Army Commander was not immediately available to give a ruling, but one was promised. A little after mid-day Norrie spoke to Messervy, saying that in his view there would have to be a complete withdrawal to the frontier. Meanwhile the 21st Panzer Division had passed on to El Duda, and the 90th Light had made another attack on El Adem while the two German reconnaissance units and the Ariete Division held off the attempts by 7th Motor Brigade to help. The 29th Indian Infantry Brigade continued to resist stoutly and the 90th Light Division, being in a bad way, was told to discontinue its attacks. At 5.30 p.m. General Ritchie (who had by now received the Commander-in-Chief’s authority to allow Tobruk to be temporarily isolated) told General Norrie that the local situation must govern the decision whether or not to give up El Adem, and because he could not tell what the situation was he delegated the decision to General Norrie. A little later Norrie decided to evacuate El Adem the same night. General Messervy had already made arrangements, and the Brigade successfully slipped away during the small hours of 17th June. In the circumstances this withdrawal was unavoidable, yet the effect, as 90th Light Division noted in its diary, was that it removed the southern corner-stone from the advanced defence line of the fortress of Tobruk.

The concentration of enemy movement towards and around El Adem had given the Desert Air Force plenty of targets at a short distance from the Gambut airfields. On the 15th June the Bostons and the fighter-bombers were out in strength, as were the new tank-destroying Hurricanes. This meant heavy escort duties for the fighters, which had also to protect convoy VIGOROUS as it returned to Alexandria. This convoy, as on the previous evening, was attracting a large part of the enemy’s air effort, and the German bombers based in

North Africa flew 193 sorties against it in the two days—another example of the interplay of sea, land, and air. Without this diversion

the air attacks on the retreating 8th Army on the evening of 14th June and during the 15th could have been much heavier than they were. But in that case the British fighters could have opposed them in strength, and although the 8th Army no doubt gained some respite

by the passage of the convoy at this particular moment, it is impossible to say how much.

The approach of the enemy so close to Gambut meant that Air Vice-Marshal Coningham was taking a risk in continuing to use these airfields. But if he withdrew the fighters thirty miles to Sidi Azeiz it would seriously limit the support they could give in the El Adem area. Behind a screen of patrols of No. 2 Armoured Car Company RAF there were four infantry battalions and three and a half antiaircraft batteries (ready to engage tanks if necessary) allotted to the close defence of the Gambut airfields for as long as he needed them, and Coningham decided to keep Gambut open for the time being and to remain there himself.

The next day, 16th June, was a particularly busy one for the Desert Air Force. In the El Adem-Sidi Rezegh area the Bostons made seven attacks and the fighter-bombers twenty. The 21st Panzer Division reported that it had been attacked for the first time by fighter-bombers firing a 2-cm. cannon which caused considerable losses in men and material.1 In the afternoon enemy fighters became increasingly active. They intercepted some of the Boston formations and followed them back to their landing-grounds at Baheira. However, only once did the Me.109s break through the escorting Kittyhawks, and no damage was done. It was undoubtedly a successful day for air support; cooperation between the 8th Army and the Desert Air Force worked well and the 21st Panzer Division had cause to report ‘Continual attacks at quarter hour intervals by bombers and low flying aircraft’, and to request urgent fighter protection.

On 17th June news of the withdrawal from El Adem seems to have travelled slowly, and did not reach the Desert Air Force until 3 p.m.—twelve hours after the event. The result was that for much of the day the Gambut airfields were in danger of attack from any columns of the enemy who might have by-passed the two remaining defended localities at Sidi Rezegh and Belhamed. As the British aircraft shuttled to and fro, the rearming and refuelling parties could hear the burst of their own bombs falling among the enemy’s foremost troops. The attacks were concentrated on the area between Sidi Rezegh and Belhamed because requests for air support were coming from the 20th Indian Infantry Brigade but none from the 29th.

The 20th Indian Infantry Brigade was a new formation which had not trained as a brigade. It had arrived in the Desert from Iraq in the first week of June and by the 10th was holding a main position at Belhamed, with a detached battalion at Sidi Rezegh.2 Late on 16th

June the 21st Panzer Division bit into Sidi Rezegh, reported stubborn resistance, and did not press on. General Norrie, however, was weighing (as he had done at El Adem) the possible loss of the Brigade against the damage it might do to the enemy. At 10.30 a.m. On 17th June he decided that the Brigade was to hold on as long as possible but would withdraw if in imminent danger of being overrun.

We must now turn to the 4th Armoured Brigade. This Brigade had been hastily reconstituted and by 16th June consisted of the composite regiments 1st/6th and 3rd/5th RTR; 9th Lancers, two squadrons strong; and a composite squadron from the 3rd and 4th County of London Yeomanry. It had under command the 1st RHA and the 1st KRRC. The brigade had about 90 tanks, but was undoubtedly a scratch affair as regards organization and equipment. On 16th June it had a brush with the enemy near Sidi Rezegh and leaguered about ten miles south-east of that place. On the morning of t 7th June the tanks were busy with maintenance, and two columns, each consisting of a horse artillery battery and an infantry company, set out—one to Sidi Rezegh and one to Pt 178—to help the 20th Indian Infantry Brigade. Early in the afternoon General Messervy ordered the whole Brigade to an area south of the Trigh Capuzzo between Belhamed and El Adem, with a view to striking at the enemy’s flank. Brigadier Richards doubted whether the area was suitable tactically, but before the brigade moved enemy columns appeared travelling rapidly eastward across it. These were in fact the 15th and 21st Panzer Divisions which Rommel had ordered to drive south-east and after a time to turn north to Gambut and cut the coast road. The British regiment closest to the enemy, the 9th Lancers near Hareifet en Nbeidat, faced north and engaged, and the 3rd/5th RTR soon came into action south-west of them. A slogging-match followed in which the British were handicapped since their artillery fire-power had been dispersed, most of the guns being with the harassing columns. After a couple of hours’ fighting it appeared that the enemy was pressing hardest against the 3rd/5th RTR. The 1st/6th RTR was ordered across to help, but because of misunderstandings a part only of the regiment got into action. The enemy kept up his attacks with the sun behind, and at about 7 p.m. Brigadier Richards began to withdraw south-eastwards. The enemy followed up until nearly nightfall and in particular severely pressed the 9th Lancers. After dark Richards decided to withdraw to a Field Maintenance Centre south of the Trigh el Abd where he would replenish and be in a position to strike at any enemy advancing eastward next day. But the Germans, who had broken off the action on Rommel’s orders, turned north, and a little after midnight the 21st Panzer Division reported that it had cut the coast road near Gambut. The 4th Armoured Brigade, with 58 fit tanks, spent

18th and 19th June in reorganization and maintenance, and was then ordered back to the Egyptian frontier.

By the time on 17th June that the 4th Armoured Brigade’s battle was ending General Norrie had concluded that Belhamed was nearly cut off. He therefore ordered the 20th Indian Infantry Brigade to withdraw to Sollum during the night 17th/18th. This withdrawal was only partially successful, for in the small hours the 1st South Wales Borderers and 3/18th Royal Garhwal Rifles ran into the German road blocks; in their uncombined attempts to run the gauntlet at dawn they were scattered and captured almost to a man. Brigade Headquarters, 1/6th Rajputana Rifles, and 97th Field Regiment, which had taken other routes, escaped.

On 17th June, as soon as Air Vice-Marshal Coningham learned for certain that the El Adem locality was in enemy hands, he ordered the Gambut airfields to be evacuated. As the enemy air forces were too busy protecting their own troops to bother about the British airfields, the fighters flew safely away to Sidi Azeiz and the airfield defence troops withdrew. Most of the day-bombers moved back from Baheira to near Mersa Matruh; the rest withdrew the following day. The tactical reconnaissance aircraft of No. 40 Squadron SAAF were already within the Tobruk perimeter. That the Desert Air Force had been able to stay in action well forward until the last possible moment is proof of its good organization. From 15th to 17th June it had been operating with skeleton maintenance crews, and ready to move at one hour’s notice. Yet the fighters had averaged 450 sorties, which means at least three flown by every available aircraft each day. The light bombers averaged 50 a day and dropped over too tons of bombs. Five German and three Italian aircraft had been shot down, while the British, not unexpectedly, lost sixteen.

Early on 18th June General Rommel reported to OKH that Tobruk was now invested and that an area extending to a distance of forty miles east and south-east of it had been cleared of the enemy. The DAK lay to the east of the perimeter, the Ariete Division to the south-east, the 10th Corps to the south, and the 21st Corps and a few German infantry to the west. Thus the rear of the intended operation against Tobruk was now safe from interference, and the British had lost the use of the Gambut airfields. Axis units had reported the discovery of large stocks of all kinds, principally in the Belhamed area and to the east of Gambut.

As late as 10 p.m. on 17th June General Auchinleck, as yet unaware of the evacuation of Belhamed and the defeat of the 4th Armoured Brigade, issued an order to General Ritchie to hold Tobruk and keep the enemy west of the general line Tobruk-El Adem-Bir el Gubi, to

hold the frontier, and to counter-attack when a suitable opportunity could be made. Ritchie had seen the Commanders of the 1st South African and 50th Divisions on 17th June, and estimated that nine 8-gun columns would be ready between 18th and 21st June. But by early morning on 18th June he realized that he was trying to do too much at once and signalled to the Commander-in-Chief that he was feeling the difficulty of acting aggressively against the enemy’s southern flank near Tobruk and at the same time implementing the plans for defending the frontier.

General Auchinleck flew up at once to discuss the matter. The outcome was that Tobruk was to come directly under Army Headquarters while the 13th Corps would be responsible for defending the frontier and for operating westward of it—in other words, for helping Tobruk from outside. The 30th Corps was to pass into general reserve in the Matruh area, where it would form and train a striking force with which, in due course, to resume the offensive. The 13th Corps, given time, would have available for its mobile operations the 7th Armoured Division (4th Armoured Brigade, 7th Motor Brigade and 3rd Indian Motor Brigade), in all sixty-six tanks and six ‘columns’, and one brigade each from the 1st South African and 50th Divisions, each contributing three ‘columns’. The rest of these two Divisions and the 10th Indian Division would occupy defensive positions on the frontier. Plans were made for two eventualities: one in which the enemy’s main thrust was directed towards the frontier, and the other in which it was made against Tobruk. The second was thought to be the more likely, but in the event the speed with which the assault on Tobruk was mounted precluded any effective help being given by the 8th Army from outside.

At this time the support which the Desert Air Force could give was rapidly dwindling. Not only had it lost the use of the Gambut airfields, but the Army could give no security at Sidi Azeiz against fast-moving enemy forces, and the DAK was known to be already well to the east of Tobruk. It was therefore necessary for Air Vice-Marshal Coningham to take the next step in his plans for withdrawal, namely to move the fighters back to airfields near Sidi Barrani. This meant that the whole fighter force, with the exception of No. 250 Squadron, whose Kittyhawks were equipped with long-range tanks, would now be out of range of Tobruk, but there was no alternative. The last aircraft took off from Sidi Azeiz on 19th June, and German reconnaissance troops were there next morning. The enemy’s air forces were unusually quiet on the 18th and 19th June, being no doubt fully occupied in preparing to make a very special effort on the 20th.

Before turning to the attack on Tobruk it will be of interest to consider the gist of a very full appreciation sent by the Commanders-in-Chief to the Chiefs of Staff on 20th June, based on the situation as

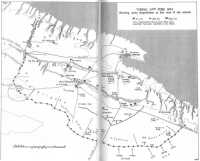

Map 29: Tobruk, 20th June 1942. Showing main dispositions in the area of the attack

from the town, giving a length of some thirty miles of front. They had been protected by barbed wire obstacles and an anti-tank ditch, but when first captured from the Italians the works had been criticized on the ground that they were refuges rather than fire positions. Within the outer ring, and about two miles from it, the Australians had constructed a second system of defence in 1941, known as the Blue Line. Both the outer perimeter and the Blue Line had been thickly mined, and between them numerous tactical minefields had been laid. The ground was generally open and sloped down from the perimeter to the town and harbour in a number of steps, of which the most prominent are the Pilastrino ridge (so-called, but in reality an escarpment, not a ridge) and the Solaro escarpment.

The 2nd South African Division inherited these defences when it arrived in Tobruk at the end of March 1942, and there is considerable conflict of evidence as to their condition both then and in June. In February 1942 the Commanders-in-Chief had decided, and it was commonly known, that Tobruk was not again to stand a siege, and with the Gazala position ranking as more important it is probable that nobody was interested in keeping the defences of Tobruk in first-rate condition. The anti-tank ditch, for instance, had not been kept in repair and in places had caved in or silted up, and large amounts of barbed wire had been lifted for use elsewhere. Moreover, the garrison had made a sortie towards El Duda during CRUSADER, for which gaps were prepared in the obstacles. Elsewhere, too, large numbers of mines seemed to have been lifted, though whether they were mostly old Italian mines or newer British mines is uncertain. Indeed by June 1942 little accurate information about the minefields or the buried telephone lines seems to have been available. Something of the state of affairs was realized by the 2nd South African Division which had been spasmodically cleaning out the existing works, making alternative gun positions, and inspecting minefields by sample checks.

The 2nd South African Division, of only two brigades, which now formed the main contingent of the garrison, had neither the experience nor the training of the 1st. It was not entirely untried, however, having captured Bardia and Sollum in January. On 14th May Brigadier H. B. Klopper had taken over command from Major-General I. P. de Villiers, who had left for an appointment in South Africa. The new commander had held important staff and training positions but had little operational experience other than at Bardia, when he had been GSO1 of the Division. The divisional staff had several newcomers in May 1942 and as a team was inexperienced.

Besides the 2nd South African Division there were three formations in Tobruk—the 32nd Army Tank Brigade (Brigadier A. C. Willison), the 201st Guards Brigade (Brigadier G. F. Johnson), and the 11th Indian Infantry Brigade (Brigadier A. Anderson). The 32nd Army

Tank Brigade now consisted of the 4th RTR of three squadrons with 35 fit Valentines between them, and the 7th RTR (with some reinforcements from the 8th and 42nd RTR) of two squadrons with 26 fit Valentines and Matildas. The battalions of the 201st Guards Brigade were the 3rd Coldstream Guards, and the 1st Sherwood Foresters and 1st Worcestershire Regiment who had just been assigned to the Brigade. The Brigade commander was a newcomer to the Middle East who had only taken over on 17th June. The Coldstream Guards were up to strength, were fairly complete in equipment, and had ten 6-pdr anti-tank guns. The Sherwood Foresters were nearly up to strength and had most of their equipment, together with four 6-pdrs, which were new to them. The Worcestershires were still recovering from the sharp action at Pt 187 on 14th June; they were about 500 strong and had little besides their personal weapons. The 11th Indian Infantry Brigade consisted of a weak anti-tank company; the experienced 2nd Cameron Highlanders; the 2/5th Mahratta Light Infantry, which contained a high proportion of young reinforcements; and the 2/7th Gurkha Rifles, who had seen little fighting as yet. Under Brigadier Anderson’s command there was also a composite battalion from the 1st South African Division named “Beergroup’ after its commanding officer, Lieut.-Colonel J. M. de Beer.

The field artillery in Tobruk consisted of the 2nd and 3rd South African Field Regiments and the 25th Field Regiment RA.3 There were two medium Regiments RA, the 67th and 68th, each with eight 4.5-inch guns and eight 155-mm. howitzers. Besides the infantry’s anti-tank guns already mentioned there were the 6th South African Anti-Tank Battery and ‘A’ Battery 95th Anti-Tank Regiment RA, both very weak. In all the garrison possessed fifteen 6-pdrs, thirty-two 2-pdrs, and eight anti-tank Bofors—not a very large provision. Antiaircraft guns were also few: eighteen 3.7-inch guns of the 4th AA Brigade RA and the light guns of the 2nd South African LAA Regiment. Eighteen 3.7-inch guns had been removed on 8th Army’s orders on 16th June, and sent back to the frontier positions.4

Many units whose primary role was not fighting had been withdrawn from Tobruk, but there remained a number of administrative establishments, under control of Headquarters 88th Sub-Area (Brigadier L. F. Thompson). Apart from vehicles with units there were ten transport companies—British, South African, and Indian. All unwanted ships, mainly storeships and lighters, were sailed for Alexandria on 16th and t 7th June. There remained a Naval Establishment under the Senior Naval Officer, Inshore Squadron, Captain P. N. Walter, RN, with a Naval Officer in charge, Captain F. NI. Smith,

RNR No. 4.0 Squadron SAAF having been withdrawn, there were now no aircraft in Tobruk. An Air Support Tentacle, however, was left with General Klopper’s Headquarters. As regards supplies, Tobruk was well provided, there being some 3 million rations, 7,000 tons of water, and 1½ million gallons of petrol. Stocks of field artillery ammunition stood at over 130,000 rounds, medium at about 18,000, two-pounder at 115,000, and six-pounder at 23,000.

On 15th June General Klopper took command of all troops within the perimeter, and at a conference held that day he told his subordinates that Tobruk would be held as part of the 8th Army’s plan (which he outlined to them) and must be prepared to resist for three months. No tactical questions were discussed, probably because Klopper had not received his detailed orders from the 13th Corps. Brigadier Willison, however, who had been through the siege in 1941, when he had been the commander of the reserve, made privately to General Klopper some suggestions for changing the organization and dispositions based on his previous experience. This was taken in good part, but produced no change. A further proposal by Brigadier Johnson, whose brigade, together with the 32nd Army Tank Brigade, would be in reserve, that he and Brigadier Willison should set up a combined battle headquarters was apparently agreed to in principle, but seems to have been deferred as being premature until the direction of the enemy’s attack was apparent.

On 16th June General Gott’s headquarters were still in Tobruk, and at a meeting with the Army Commander he suggested that he should remain to take command. General Ritchie did not agree, and that afternoon Gott departed, leaving three of his staff to assist General Klopper in administrative matters. His final instructions to Klopper were to make three more sets of plans: for co-operating at once with the harassing forces outside Tobruk in keeping open its lines of communication, for re-establishing the Belhamed locality in conjunction with the 30th Corps, and for the withdrawal of the Tobruk garrison eastwards, covered on the south by the 30th Corps. This was a considerable addition to the already heavy burden on Klopper and his staff.

General Klopper held his next conference on 18th June but, beyond declaring that Tobruk was now besieged and would be held, he announced no new plans or dispositions. Brigadier Willison again offered some suggestions, his main point being that the chance of a landing by sea was very slight compared with an attack against the perimeter, and that the number of troops locked up in guarding the coast was excessive. Again he received a courteous hearing, but General Klopper seems to have been satisfied and quietly confident. He had written in this spirit to General Theron in Cairo on 16th June, and on the 18th signalled to General Ritchie that the position was

very satisfactory, and that his harassing of the enemy was being effective.

The dispositions of the garrison at dawn on 20th June were as shown on Map 29, with the 6th South African Infantry Brigade in the north and north-west, and the 4th South African Infantry Brigade in the centre holding as far east as a point about one mile west of the El Adem road. From there to the sea was held by the 11th Indian Infantry Brigade, whose units from west to east were ‘Beergroup’, the 2nd Cameron Highlanders, the 2/5th Mahratta Light Infantry, and the 2/7th Gurkha Rifles. In garrison reserve the 201st Guards Brigade was disposed above, and the regiments of the 32nd Army Tank Brigade below, the Pilastrino ridge.

The 2nd and 3rd South African Field Artillery Regiments were supporting the two South African Infantry Brigades, and the 25th Field Regiment RA was supporting the 11th Indian Infantry Brigade. The 68th and 67th Medium Regiments RA were allotted to the western and eastern halves of the whole front. It was General Klopper’s intention that the artillery should fight as a whole under his CRA, Colonel H. McA. Richards, but no orders to carry out this intention can be traced. Plans for counter-attacks—doubly important when the perimeter is long for the number of defending troops—remained nebulous as far as Divisional Headquarters were concerned, although Brigadier Johnson had on 16th June made some tentative arrangements with the commanding officers of the 25th Field Regiment RA and the 2nd South African Field Regiment. General Klopper’s own Headquarters was divided into two separate portions and was centrally situated in the so-called Pilastrino caves, where the road from Pilastrino to the harbour crosses the Solaro escarpment.

The enemy had made several attempts to capture Tobruk’s last outpost at Acroma, whose small garrison from the 2nd Transvaal Scottish and Die Middellandse Regiment resisted stoutly until withdrawn on 18th June. South African armoured cars and small mobile columns kept an eye on the enemy and reported him to be thickening up on the south-east, south, and west. From which of these directions would the attack come? It was General Auchinleck, distant in Cairo, who most clearly read the signs. At 6.30 a.m. on 20th June he signalled to General Ritchie: ‘Enemy’s movements yesterday show intention launch early attack Tobruk from east ... ’ And an hour later, ‘Am perturbed by apparently deliberate nature your preparations though I realize difficulties. Crisis may arise in matter of hours not days and you must therefore put in everything you can raise ... ’ Before the first of these messages was sent the attack on Tobruk had already begun.

A word of explanation is called for about the sources from which the rest of this chapter is drawn. In the fighting at Tobruk on 20th and 21st June the British garrison was defeated and only a few escaped capture. Almost all the relevant contemporary documents are missing. The story has therefore had to be built up from the personal accounts of individuals after their return from captivity, and of those who avoided capture. Between their various versions there are many points of difference. The German records have been useful, but it is difficult to reconcile their timings with those given by British eyewitnesses from memory. The net result is that the sequence of events is probably fairly correct, though the actual timings are open to doubt. In some of the detailed fighting it is impossible to be sure what occurred.5

General Rommel had lost no time in deciding upon his front of attack, which was the same as he had chosen for the intended assault in the previous November—namely, the south-east. The positions of his German troops in the area El Adem–Belhamed–Gambut were well suited to this, and the plan was for the DAK to attack the sector which happened to be held by the 2/5th Mahratta Light Infantry, with the 21st Panzer Division on the right, the ‘Menny’ group of the infantry of the 90th Light Division in the centre, and the 15th Panzer Division on the left. The 20th Italian Corps was to attack still farther to the left, which brought it opposite the front held by the Cameron Highlanders. Behind the DAK would follow one division of the 10th Corps to occupy the captured posts, and its second division would be around El Adem. Farther south would be the newly arrived Littorio Division, while in the direction of Bardia and Sidi Azeiz the 90th Light Division, less the Menny group, together with the 3rd and 33rd Reconnaissance Units, would hold the attention of the British on the frontier.6

As regards timing, General Rommel decided that it would be better to take advantage of the disorganization that had followed the British defeat than to spend much time in making elaborate preparations. He had obtained the willing consent of Field-Marshal Kesselring to use the Luftwaffe at its greatest possible strength to deliver a highly concentrated attack on the front to be assaulted. Kesselring was, as

we know, anxious to have done with Tobruk and turn again to Malta, and the clearly defined target no doubt made the idea an attractive one from his point of view, particularly as the distance from the nearest British airfields made it unlikely that there would be any appreciable opposition in the air.

General Rommel issued his orders for the attack on 18th June. Reconnaissances were to be made on the 19th; otherwise no movements towards the assembly positions were to begin before the late afternoon. This drew something of a protest from the DAK, but a personal visit by Rommel quickly made it clear that the original order held good. An entry in the DAK’s diary that evening gives a hint as to their doubts. It reads: ‘The fact that the divisions will move during darkness into an assembly area with which they are unfamiliar will probably not work out badly.’ Nor did it; the reconnaissances had no doubt been very thorough, and the handicap to the artillery in moving into their positions so late was to a large extent offset by the use of aircraft to open the bombardment of the perimeter defences.

In the event every bomber unit in North Africa was drawn upon, and some aircraft were even transferred there from Greece and Crete. The total force of serviceable aircraft actually used against Tobruk on 20th June consisted of some 80 to 85 bombers, 21 dive-bombers (Stukas) and 40 to 50 fighter-bombers, the majority German—a grand total of some 150 bombers of various types. In addition there were about 50 German and over loo Italian fighters available as escorts. The nearness of the landing-grounds at Gazala and El Adem made possible the ‘shuttling to and fro’ remarked by eye-witnesses, and in this way the German aircraft flew no less than 580 bomber sorties in the day (30 of which were from Crete), and the Italians 177. The German share of the total bomber load was well over 300 tons and that of the Italians probably about 65 tons. Two Stukas were lost in a collision, one Me.110 crash-landed, but the Italians suffered no losses.

A brief summary of the day’s progress from the point of view of the attackers will serve as a background to the somewhat confused story of the defence. By 4 a.m. the troops were in position, well back from the perimeter. At about 5.20 the bombers began to pound the sector between the Tobruk-Bardia and Tobruk-El Adem roads. The Menny group then worked forward and shortly before 7 a.m. was ready to assault. The engineers made crossings over the anti-tank ditch and by 7.45 the tanks were ordered to advance. By now several of the foremost posts had been captured and the infantry were reported as making good progress. The first tanks of the 15th Panzer Division crossed the ditch at 8.30 and those of the 21st Panzer Division not long afterwards, having been delayed in traversing the minefield. The Ariete also crossed the ditch, but met strong opposition and failed to

get through the wire. Part of 20th Corps was therefore ordered to follow 15th Panzer Division, which had driven back some British tanks ‘in a stubborn fight’ and was steadily advancing towards the road junction (King’s Cross). By 1 p.m. the 21st Panzer Division had caught up and half an hour later Rommel announced that the dominating heights four to five miles from the harbour (i.e. King’s Cross) had been captured. Shortly after 2 p.m. the harbour came under artillery fire. The 21st Panzer Division’s advance was then directed on Tobruk, while the 15th was to protect its left flank by operating towards Fort Solaro. (It actually moved west above the Pilastrino ridge.) At 5 p.m. the 21st Panzer Division asked that fire on the town and harbour should cease, and at 5.15 reported that it was advancing from the airfield towards Tobruk. At 7 p.m. it reported that the town had been captured. At 8 p.m. General Rommel ordered the occupied areas to be mopped up, embarkations to be prevented, and the attack to be continued at first light next day.

The extremely heavy air and artillery bombardment, which was heaviest in the neighbourhood of Post R 63, effectively neutralized the defenders, and by about 7.45 a.m. a breach had been made between Posts R 58 and R 63 and the 2/5th Mahrattas had committed their reserve to an unavailing local counter-attack. At about 7 a.m. Brigadier Anderson had ordered the carrier platoon of 2/7th Gurkhas over to the threatened point, and had reported to General Klopper that his front had been penetrated but counter-measures had been taken and things were in hand. Klopper’s reply gave Anderson to understand that a battalion of tanks and some infantry were being sent up to counter-attack.

Soon afterwards, Headquarters 11th Indian Infantry Brigade realized that events were taking an ugly turn and reported accordingly to the Division. At 9.30 Brigadier Anderson telephoned in person, for there was as yet no signs of the counter-attacking force which he was expecting to meet and steer into action to seal off the German penetration. By 10 a.m. resistance by the Mahrattas had ceased.

General Klopper’s intention had been that the counter-attack force should be under command of 32nd Army Tank Brigade, who would make whatever arrangements were necessary with the Guards Brigade and 11th Indian Infantry Brigade. The orders issued do not seem to have been understood in this sense; at any rate Brigadier Johnson and Brigadier Willison never met, although the former, listening to the noise of battle, had already suggested opening a joint battle headquarters near King’s Cross. Willison called Lieut.-Colonel W. R. Reeves of the 4th RTR to his own headquarters and ordered him to counter-attack in the south-east sector. Reeves returned to his

battalion and got his tanks on the move, but valuable time had been lost in the journey to and from Brigade Headquarters. Meanwhile, two companies of the Coldstream Guards and a platoon of anti-tank guns had been ordered to move to a point near King’s Cross and to stand by for counter-attack. At about 9.30 the officer commanding this detachment met Colonel Reeves, whose tanks were just going into action and who had certainly not grasped that any infantry were to co-operate with him. The detachment commander reasonably decided that as there was no plan his small force could do nothing but await events.

Colonel Reeves took his battalion forward to hull-down positions covering known gaps in the Blue Line minefields. The German tanks appeared to be moving north and fanning out east and west, but their movements were slow and the fire of the tanks and of the 25th Field Regiment seemed to be holding them in check. Meanwhile Brigadier Willison had ordered the 7th RTR to concentrate west of King’s Cross, and Lieut.-Colonel Foote, moving ahead of his battalion, met Lieut.-Colonel Reeves. They agreed that the situation was serious but not desperate, and that there was a prospect of stopping the enemy on the Blue Line. Colonel Foote decided to bring his battalion up on the right (i.e. south) of the 4th, but first sought out Brigadier Anderson, to whom he imparted his opinion and decision. Anderson agreed, but asked that one squadron—the battalion had only two—should be sent south to support the Cameron Highlanders.

At Divisional Headquarters all seemed well enough. General Klopper had been expecting the assault to open with a feint and seems to have thought at first that a feint was in fact being made. (This is surprising in view of the concentration of aircraft and the tremendous din.) When it was clear that this was the real thing, it seemed at divisional headquarters that a counter-attack had been ordered in good time and the absence of news of its progress was taken to mean that nothing untoward was happening. Then came a reassuring report from Brigadier Anderson based on his conversation with Colonel Foote. Two troops of the 5th South African Field Battery and the 9th South African Field Battery were successively ordered to the King’s Cross area, but nothing else was done. The Air Support Tentacle had reported to Advanced Air Headquarters what was known of the situation, and as a result nine Bostons escorted by long-range Kittyhawks were sent to attack vehicles concentrated near the gap in the perimeter.

Just before noon the German thrust began again in three prongs, all converging on King’s Cross: one along the Bardia road, one from the south-cast, and one from the south. The events and timings of the mêlée which followed are uncertain, but the result is quite clear. By about 2 p.m. all the artillery on and in front of the Blue Line had been destroyed with the exception of a few detachments. The 4th

RTR had ceased to exist as a unit, and its surviving tanks, perhaps six, joined the 7th Battalion. The squadron sent to support the Cameron Highlanders had been recalled and was destroyed en route. Headquarters 11th Indian Infantry Brigade had been scattered and was moving to a rendezvous south of Tobruk town.

Although King’s Cross had passed into enemy hands only vague information reached Divisional Headquarters until Brigadier Anderson arrived between 3 and 4 p.m. with some account of the situation. General Klopper, however, had already heard enough to make him uneasy, and at about 2 p.m. he ordered the Guards Brigade to form a new line facing east and to deny the Pilastrino ridge to the enemy. He ordered Brigadier Hayton, commanding 4th South African Brigade, to take over the Cameron Highlanders and ‘Beergroup’ and reorganize the defence in that area. He also instructed the 4th and 6th South African Brigades to prepare a company each to attack the German leaguers the same night.

The two parts into which the German advance now divided—the thrust of 21st Panzer Division towards Tobruk and the attack of 15th Panzer Division along the Pilastrino ridge—will here, for the sake of clarity, be treated separately.

At about 2.30 p.m. the 21st Panzer Division began to descend the escarpment from King’s Cross by the road running north to Tobruk. It met and scattered the remains of the 7th RTR, and there was now nothing between it and Tobruk except the 9th South African Field Battery and a troop of the 5th, a troop of the 231st Medium Battery RA and four guns of the 277th Heavy Anti-Aircraft Battery RA. The field guns delayed the advance until about 4 p.m. when they were forced westwards. Rommel wrote of the ‘extraordinary tenacity’ of a British strong-point near ‘the descent into the town’; it was about here that some of 5th Panzer Regiment’s tanks came under the close fire of the heavy anti-aircraft guns, which claimed to have disabled several of them.7 At about 6 p.m. the leading German troops began to enter the town.

The German advance had naturally caused a crisis in No. 88 Sub-Area. The commander, Brigadier Thompson, after several personal reconnaissances, obtained General Klopper’s agreement to put the demolition scheme in hand. At about 6 p.m., on his own initiative, he ordered demolitions to begin. Although time was now very short a large amount of damage was done to the petrol and water installations, and to the harbour facilities. Brigadier Thompson himself was taken prisoner, fighting on a roof. All craft had meanwhile been ordered to sail for Alexandria and left harbour under fire, partly covered by a smoke-screen laid by a MTB. The last craft, containing the naval demolition parties, was sunk in the harbour; Captain Smith was

mortally wounded and Captain Walter wounded and captured. In all, two minesweepers and thirteen craft of various sorts escaped, and one minesweeper and a total of twenty-four launches, tugs, schooners, and landing craft were lost in harbour or on passage to Alexandria.

A crisis had also occurred at Divisional Headquarters. Reports during the afternoon were scanty, and at 4 p.m., while shells were falling around and a miscellaneous collection of men and vehicles were passing through, apparently from Pilastrino, tanks were seen to the east. General Klopper judged that his headquarters would be overrun in a matter of minutes, and ordered his staff to destroy their documents and disperse. A rendezvous was appointed at Sollum. The signal office, telephone exchange, and most of the wireless sets were destroyed; only a few sets in trucks survived. The German tanks, however, moved away, but Divisional Headquarters was now in a state of self-inflicted paralysis. At about 6.30 Klopper decided to move to the headquarters of the 6th South African Brigade at Ras Belgamel in the north-western sector, but his earlier decision to disperse his own headquarters had deprived him of the means of exercising command.

We must now return to the Pilastrino ridge, above (i.e. to the south of) which the 201st Guards Brigade was now disposed from a point about one mile south-west of King’s Cross to Fort Pilastrino four miles away. From cast to west were the Sherwood Foresters, Brigade Headquarters, the Coldstream Guards, and, in the Pilastrino area, the Worcestershires. These dispositions required some little time to take up; for instance two companies of the Coldstream Guards, as has been related, had been sent earlier in the day to near King’s Cross. There was practically no natural cover at all and the rocky ground made digging almost impossible.

The attack by 15th Panzer Division along the ridge began at about 5 p.m. Two companies of the Sherwood Foresters were soon overrun, the Coldstream Guards were engaged, and at about 6.45 Brigade Headquarters was captured. It seems that a message reached the Sherwood Foresters from Brigade Headquarters that the brigade was surrendering, and their remnants ceased to resist. Major H. M. Sainthill. commanding the 3rd Coldstream Guards, extricated his No. 4 Company, some fifty survivors of the other companies, and six antitank guns, and withdrew to Fort Pilastrino. The Germans (whose role was to protect the flank of the advance on Tobruk town) did not follow up.

In the meantime Brigadier Hayton had told Lieut.-Colonel Geddes Page of the Kaffrarian Rifles, which lay west of ‘Beergroup’, to contact ‘Beergroup’ and the Cameron Highlanders. Some tanks were roaming about in this area and a shell destroyed the Kaffrarian

Rifles’ wireless link. From the subsequent silence Brigadier Hayton concluded that the battalion had been overrun. At Fort Pilastrino he had no news of the general situation, and at about 4 p.m., on a report of tanks in the distance, he decided to move his headquarters four miles to Fig Tree. The move was confused, and for the next three hours the 4th South African Brigade was without command. Just about the time when this headquarters moved, Lieut.-Colonel I. B. Whyte, commanding the 3rd South African Field Regiment, unable to gain touch with the Brigadier or the CRA or the divisional headquarters, decided that something must be done. He and Lieut.-Colonel O. W. Sherwell, of the 2nd South African Field Regiment, resolved to concentrate their guns (about fifty in number) at Fort Pilastrino and there withstand an enemy advance from the east. He then conferred with Lieut.-Colonel J. O. Knight of the Worcestershire Regiment and Major Sainthill of the Coldstream Guards and all agreed to fight it out where they were. But these stout-hearted officers were fated to have no chance to carry out their resolve.

The situation at nightfall was broadly as follows. In the extreme east the 2/7th Gurkha Rifles were resisting attempts to mop them up. In the south the Cameron Highlanders, ‘Beergroup’, and the Kaffrarian Rifles, which had been by-passed by the main German thrust, had prepared for all-round defence. The Coldstream Guards, the Worcestershire Regiment and Colonels Whyte and Sherwell with their guns were preparing to give battle at Pilastrino. The 6th South African Brigade had not been engaged and the 4th had dealt with demonstrations only. Brigadier Willison, with General Klopper’s permission, was planning to break out with the survivors of his brigade, on wheels. In the administrative areas round the town and harbour there was confusion and chaos. Into the western sector of the perimeter there was a steady percolation of miscellaneous stragglers, the backwash of the day’s fighting. General Klopper and some of his staff were at Headquarters 6th South African Brigade, but had lost control. The enemy had gone into leaguers for the night. At last light a small force of Bostons made an attack on targets in the south-eastern sector, and single Bostons came over during the night: this was all that the Royal Air Force could do.

Until the dispersal of Divisional Headquarters the signal communication with 8th Army had been fairly good, though there were considerable delays. By 4.30 p.m. the advance of enemy tanks to a mile west of King’s Cross had been reported, and at about 6 p.m. came the news that the garrison had no tanks left and that the eastern sector had been badly mauled. A naval signal then brought word that tanks were approaching Tobruk harbour. It was at about this time that

General Klopper reached the 6th South African Brigade’s headquarters. He had decided that the position of his troops was hopeless and issued a warning order that all units should prepare for a mass break-out at 10 p.m. At 8.8 p.m. he sent a message to 8th Army: ‘My HQ surrounded. Infantry on perimeter still fighting hard. Am holding out but I do not know for how long.’ This message, received shortly after midnight, confirmed the impressions which had been steadily growing that the situation in Tobruk was desperate. Earlier in the day General Ritchie had ordered the Both Corps to push the 7th Armoured Division northwards to Sidi Rezegh, but it is evident from the enemy’s reports that the ring was in no danger of being broken. Indeed, writing shortly after the event, General Ritchie recorded that ‘I deplore more than ever that I found it impossible in the circumstances to give General Klopper any material assistance by operations from outside. The fact is that I was being held off by considerable enemy forces which could so delay my advance as to make this impossible in the time the enemy took to reduce Tobruk.’

About 9 p.m. there began an exchange of messages by radiotelephone between the BGS 8th Army and General Klopper, of which short notes exist. Brigadier Whiteley asked if the situation was in hand and for how long Klopper could hold out. The answer ran ‘... Situation not in hand. Counter-attack with lnf Bn to-night. All my tanks gone. Half my guns gone. Do you think it advisable I battle through? If you are counter-attacking let me know.’ This was referred to General Ritchie, and the BGS replied: ‘Come out tomorrow night preferably if not tonight. Centre line Medauar-Knightsbridge-Maddalena. I will keep open gap Harmat-El Adem. Inform me time selected and route. Tomorrow night preferred. Destruction petrol vital.’ With this General Klopper had to be content and a sad series of discussions took place with Brigadier Hayton, Brigadier Cooper, Colonel Richards, and others. Brigadier Anderson awaited orders near-by but took no part in the debate. Brigadier Hayton said that it was impossible to break out without transport and no one knew what had happened to the transport.8 He advocated a stand in the western sector. Brigadier Cooper on the other hand was prepared to attempt a break-out. Other officers, among them the CRA, argued that the position was hopeless mainly because the artillery now had only the ammunition in its limbers which would not last long. They suggested that all mobile troops, at least, should escape.

At length at about 2 a.m. on 21st June General Klopper sent this message to 8th Army: ‘Am sending mobile troops out tonight. Not possible to hold tomorrow. Mobile troops nearly nought. Enemy captured vehicles. Will resist to last man and last round.’ This decision

was approved by most of his subordinates but viewed with misgiving by some. A certain amount of digging and other defensive preparations had been going on, and were continued. Some time between 5 and 6 a.m. however General Klopper changed his mind and concluded that the advantages that he could gain for the 8th Army by prolonging resistance would be negligible, and would not justify the casualties that must be expected. Some time about 6 a.m. General Ritchie at last made touch with Klopper, and this record of their exchange of messages remains:

‘Army Comd. Noted about mobile elements. In respect remainder every day and hour of resistance materially assist our cause. I cannot tell tactical situation and must therefore leave you to act on your own judgement regarding capitulation. Report if you can extent to which destruction POL effected.9

GOC Situation shambles. Terrible casualties would result. Am doing the worst. Petrol destroyed.

Army Comd. Whole of Eighth Army has watched with admiration your gallant fight. You are an example to us all and I know South Africa will be proud of you. God bless you and may fortune favour your efforts wherever you may be . .

For both commanders these minutes in which each had to admit failure—the one to hold on, the other to help—must have been bitter indeed.

Soon after this General Klopper sent out parlementaires and it was not long before the German officers charged with receiving the surrender arrived at his headquarters. The orders to surrender took some time to communicate to units and were received with general amazement and often with disbelief. Once however they were understood there was a general destruction of weapons and equipment. Last to surrender were the Gurkha Rifles on the evening of list June, and the Cameron Highlanders—after a threat of extermination if they persisted in disregarding a general capitulation—on the morning of 22nd June. Numerous small parties and individuals did their best to escape, but the only considerable successful attempt was led by Major Sainthill of the Coldstream Guards. He collected 199 officers and men of his battalion, all his remaining anti-tank guns, and 188 men of other units. This column burst out of the perimeter in the south-west corner and near Knightsbridge was picked up and escorted to safety by South African armoured cars working with the 7th Armoured Division. There were some notable lesser attempts: Lieut. L. Bailie and Sergeant G. R. Norton of the Kaffrarian Rifles with a small party reached the El Alamein position 38 days after the fall of Tobruk.

Sergeants J. H. Brown and C. A. Turner of the Coldstream Guards who, in carriers, had fallen behind Major Sainthill’s column, struggled on and brought their men and machines safely in.

The number of prisoners taken at Tobruk is not known for certain, but was probably made up of:

| British troops | 19,000 |

| South African Europeans | 8,960 |

| South African Natives | 1,760 |

| Indian troops | 2,500 |

| Total | 32,220 |

or perhaps 33,000 in all.

The booty captured at Tobruk and Belhamed, and in various dumps in the desert, gave the Germans practically everything they needed except water. The Panzerarmee’s figures show that of a total of over 2,000 tons of fuel about 1,400 tons were found at Tobruk and only 20 tons at Belhamed. Large quantities of ammunition, both British and German, were found, together with some 2,000 serviceable vehicles and about 5,000 tons of provisions.

The German casualties for 20th June are not known, but were certainly light. Their total casualties since the beginning of the fighting on 26th May were reported to OKH on 24th June as having been approximately:

| Officers | 300 |

| NCOs | 570 |

| Other ranks | 2,490 |

which represented about 15% of their strength. The officer casualties had been particularly high, reaching as much as 70% in the Panzer units and in the lorried infantry.

The fall of Tobruk came as a staggering blow to the British cause. For South Africa it was particularly tragic, since about one third of all her forces in the field went into captivity. The suddenness of the collapse, almost before it was generally realized that the place was again being besieged, made the shock all the greater. Tobruk had previously withstood a siege for seven months: how came it, then, that a garrison of much the same size could only resist for one day? First Singapore and now Tobruk. What hope was there, on this showing, of saving Egypt? Worse still, what was the matter with British arms?

Small wonder that the Prime Minister, who heard the news in Washington, felt that it was one of the heaviest blows of the war. This climax to a series of misfortunes and defeats was among the reasons which caused a motion expressing no confidence in the central direction of the war to be tabled in the House of Commons on 25th June.10

The reasons for the disaster are plain enough. In the first place it had been commonly known since February that there was no intention of accepting a second siege. This knowledge led to Tobruk not being properly prepared to withstand a siege or even a determined assault. It seems clear that in making their plans after the withdrawal from the Gazala positions neither General Auchinleck nor General Ritchie realized the full extent of the 8th Army’s defeat. Had they done so, they would scarcely have attempted to carry out three simultaneous policies—to continue the battle in the Tobruk area, to organize the defence of the frontier, and to prepare for a counter-offensive. In the narrower field of tactics there can be no doubt that the commander and staff of the 2nd South African Division had not the experience to enable them in the difficult circumstances to make the best use of the forces available. Whether the best would have been good enough against Rommel and his Panzerarmee, exhilarated by success and by the nearness of the prize, is another matter—especially as he was supported by strong and concentrated air forces which had the stage practically to themselves because almost all the fighters of the Desert Air Force were out of range. The resulting onslaught was devastating; apart from the shelling nearly 4.00 tons of bombs were dropped in a short time on a very small sector of the defences.

For General Rommel the triumph must have been all the sweeter for having been so boldly and so easily won. It seemed to open the way for the quick conquest of Egypt. The world rang with his fame, and he was immediately promoted Field-Marshal. It was a great moment, and no Fate whispered that he would never experience a greater.

Blank page