Chapter 5: Deployment of the AAF On the Eve of Hostilities

Deployment of the Army Air Forces in 1941 was determined by the broad character of the AAF mission and by the existence of threats to our national interests from both the east and the west. As a component of the Army, the AAF was charged with “the preparation for and the execution of air operations” in defense of continental United States and our overseas possessions, and with similar responsibility for “operations outside the United States and its possessions as required by the situation.”1 The comprehensive nature of this mission demanded under the circumstances of 1941 a wide dispersal of Army air units, and at the same time, an effective concentration of experienced personnel within our continental limits for the organization and development of a gigantic program of expansion. it is not surprising, therefore, that the establishment of priorities and the allocation of units proved to be especially difficult tasks.

The number of fully trained and equipped units was not enough to meet all demands, a state of affairs shared by the AAF with other branches of the Army.2 At none of the overseas stations in 1941 was the local air contingent regarded as adequate – in strength, training, or equipment – to fulfill its mission; nor could any of them have been substantially reinforced except at grave cost to a training program which carried the chief hope of a prompt fulfillment of plans for a greatly expanded air force. But the AAF was rapidly gaining strength and there was reason to believe that achievement of the goals initially set was not too far distant. Moreover, if the AAF did not at the moment have all the units needed, it at least had a guide in parceling out its limited strength. As a result of the strategic plans discussed in

the preceding chapter, American air units were deployed in accordance with a larger scheme of action, which in the test of war would be proved essentially sound.

The Zone of the Interior

During the months just prior to active American participation in the war, the responsibilities and organization of air commands in the Zone of the Interior underwent several changes which were designed to improve the air defense of continental United States. According to accepted doctrines of Army air defense in 1940, the GHQ Air Force had two major combat functions: it was to operate as a striking force against enemy targets far beyond the range of other land-based weapons, and it was to provide the necessary close-in air defense of the most vulnerable and important points in the United States. The latter objective was not intended to include air protection of the entire continental coast line but was aimed at limiting the effectiveness of air attack upon vital areas.3 Antiaircraft artillery forces likewise had definite responsibilities in the event of enemy air action against the United States. In the light of British experience, however, air defense appeared to be a very complicated matter, involving the use of highly accurate means of detection, the development of both active and passive defense measures, and the coordination of military and civilian agencies. The United States in 1940 possessed only a few elements essential to air defense; it had neither a system nor a single agency responsible for protection against air attacks. But by 7 December 1941 a series of tests in the United States and firsthand study of British experience had resulted in formation of plans for air defense of the continent, and the AAF had emerged as the military agency responsible for that defense.

A first step toward coordination of air defense was taken early in 1940 when the War Department created the Air Defense Command. Headed by Brig. Gen. James E. Chaney and located at Mitchel Field, N.Y., the command was primarily a planning agency, charged with development of a system of unified air defense for cities, vital industrial areas, continental bases, and armies in the field. Although limited in size to a staff of only ten officers, the command undertook to study the special capabilities of pursuit aviation, antiaircraft artillery, radio equipment, barrage balloons, and passive defense measures, and to formulate the most effective combination of the several means of

defense. Under a strict interpretation of air defense, the new organization was not concerned with air striking units, which were designed to seek out and destroy hostile aviation great distances away was concerned only with the problem of protecting important areas and installations by interception and destruction of attacking enemy forces.4 Since the Air Defense Command was only a planning body, pursuit aviation remained under the jurisdiction of the GHQ Air Force.

In order to observe an air defense system in wartime operation, several groups of Army officers visited the British Isles in 1940 and returned with enthusiastic reports of the organization which was demonstrating its effectiveness against the Luftwaffe. By means of secretly developed radio detector instruments and a network of ground observers, the British had perfected a warning system which made possible the use of a ground, rather than an air, alert.5 Knowing accurately the altitude, speed, and course of approaching enemy formations, the British defending forces were able to keep their interceptor aircraft on the ground until the appropriate time for them to take off and engage the enemy. This method was far more efficient than the older procedure of operating continuous air patrols in the hope of discovering and intercepting hostile aircraft. Studies already made in the United States had indicated the important function of radio detector devices in air defense, and the Signal Corps was making progress in development of the special equipment.6 Consequently, in May 1940 the War Department directed that commanders of armies and overseas departments prepare or revise plans for an aircraft warning service which would include provision for use of detectors.7

The necessity for new radio equipment having been established, the Air Defense Command drew up detailed plans for a typical aircraft warning service with its three essentials: radar stations, a ground observer system, and filter and information centers. Procedures for the service were worked out in a test sector in the northeastern part of the United States, and methods were devised for coordinating the aircraft warning system, antiaircraft artillery, and interceptor aviation. It appeared, as a result of initial studies, that the organization for air defense of the United States should be based upon “strategic air areas” rather than upon a single command agency or upon any existing territorial divisions such as army or corps areas.8 Other factors in 1940 were working toward establishment of air areas in the United States;

because of the increasingly heavy responsibilities of the GHQ Air Force a decision was made to decentralize its training and tactical control, and accordingly four air districts were activated in January 1941 and the air units were assigned to these districts.9

Prolonged discussion of the assignment of the air defense mission terminated in a series of decisions announced in the spring of 1941. In March the entire responsibility for continental air defense for the first time was vested in one agency, the GHQ Air Force. At the same time the War Department established four strategic areas in the United States. Designated as the Northeastern, Central, Southern, and Western Defense Commands, the new agencies were to plan for complete, as opposed to solely air, defense of the areas. The existing air districts were redesignated as the First, Second, Third, and Fourth Air Forces, and to them, respectively, was delegated responsibility for air defense planning and organization along the eastern seaboard, in the northwestern and western mountain areas, in the southeastern area, and along the west coast and in the southwest. The areas assigned to the air forces were not entirely coterminous with the areas of the new Army defense commands. Adopting methods and procedures which had been developed by the Air Defense Command, the air forces organized interceptor commands which studied the air defense needs of their respective areas and established the foundation for aircraft warning systems with the widespread enlistment and training of civilian volunteers.10

For several reasons, the air defense of the United States was still incomplete on 7 December 1941.* There was a critical shortage of both radio equipment and aircraft of all kinds; the four air forces were charged with the training of combat units as well as providing continental air defense, and the dual responsibilities were more than could be discharged in view of the current shortages of experienced personnel and matériel. Nevertheless, significant advances had been made in the concept of a unified air defense and in the strategic area approach to the problem: large-scale Army maneuvers had tested the methods of air defense under simulated wartime conditions; plans had been made for civilian cooperation in air raid protection of large cities and other likely objects of enemy attack; and provisions had been made for a number of observation posts and filter and information centers. The preparations were not elaborate, for joint Army

* See Chapter 8.

Air Offensive Against Germany, AWPD/1

and Navy estimates did not visualize large-scale attacks on either the Atlantic or the Pacific coast in the initial stage of enemy operations. Carrier attacks and other types of unsustained assault were regarded as possible, and defensive preparations were made on the assumption that the exact locality of such attacks could not be foreseen and that priorities for protection of vital areas would be assigned only in the most general terms.11 The primary emphasis in American defense during 1941 was therefore on reinforcement of overseas bases, for so long as these were held, the likelihood of a serious attack upon continental United States was considered to be slight.

The reorganization of air commands and readjustment of responsibilities on the Zone of the Interior during the months prior to hostilities provided a model for overseas commands. Because of the integration of Army air units, both service and combat, into the AAF and the organization of the four air forces and their bases into the Air Force Combat Command in June 1941, the Army air arm by the following December was structurally well suited to the performance of its defense mission on the continent. Likewise of importance, the several air functions had been clarified and delineated in the organization of bomber, interceptor, air base, and air support commands within the several air forces. Overseas air units, although under the jurisdiction of local department commanders, reflected these continental concepts of organization and responsibility.

The North Atlantic

Army air units in Newfoundland, Greenland, and Iceland were few in number and small in size, but they were scheduled to be reinforced as rapidly as trained units became available in the United States. A large part of the activity in the North Atlantic was concerned with establishment and improvement of installations needed along the air route to Great Britain.* In an attempt to complete a network before winter began to close in, small detachments of Army airmen were rushing their work on communications and weather stations in Labrador, Baffin Island, Newfoundland, Greenland, and Iceland. By December 1941 ten stations, composing the skeleton of the Army’s first airways communications system outside the continent, extended in a thin line across the North Atlantic to the British Isles.12 Defense of these vital installations was a part of the mission of Army air units

in the North Atlantic, but the total mission was much more comprehensive and the means of accomplishment were dangerously inadequate. The First Air Force, with headquarters at Mitchel Field, New York, was acting as a major source of supply in the initial garrisoning and defense of North Atlantic bases. To the normal responsibilities of the I Interceptor Command was added the task of planning for the air defense of Nova Scotia and Newfoundland; detector sites were selected in cooperation with Canadian authorities, and representatives of the two nations worked toward a standardization of aircraft warning procedures in the area.13

The first movement of U.S. troops into Newfoundland occurred in January 1941 when a garrison arrived at St. John’s to form the nucleus of the Newfoundland Base Command.14 The command was ordered to defend U.S. military and naval installations in Newfoundland, to cooperate with Canadian and British forces defending Newfoundland and Canadian coastal zones, to support U.S. naval forces, and within prescribed boundaries to destroy any German and Italian naval, air, and ground forces encountered.15 Command difficulties arising from the presence of several nationalities at first hampered American forces in accomplishment of their mission; but unity of command for all forces on the island, which might have alleviated the difficulties, was obviously impossible so long as Canada was at war and the United States was not.

Initial plans for Army air garrisons called for a composite group,* numbering 263 officers and 2,842 enlisted men, to be stationed at the Newfoundland Airport at Gander Lake, but only one squadron had reached the station by the end of November 1941. A pursuit squadron was scheduled to be stationed at Argentia, site of a U.S. naval base on Placentia Bay, while Army airways detachments were planned for St. John’s airport on the eastern coast and for Harmon Field, Stephenville, in the western part of the island. In May 1941, the First Air Force sent the 21st Reconnaissance Squadron, equipped with six B-18’s, to the Newfoundland Airport, and in the following month eleven transport planes were allotted to the base command for moving supplies and men to the island. In August, when a few heavy bombers became available for transfer to Newfoundland, the 41st Reconnaissance Squadron replaced the 21st Squadron, and the defending air

* A composite group was made up of squadrons equipped with different types of planes.

force was then composed of 8 B-17B’s, 53 officers, and 449 enlisted men, plus an air base squadron.16 Under the guidance of Maj. Gen. Gerald C. Brant, Army commander in Newfoundland, policies on joint operations were arranged for the new B-17’s and for B-18’s operated by Royal Canadian Air Force units stationed at the Newfoundland Airport. Air operations were confined largely to reconnaissance, but occasional attacks were made against German submarines which approached the island shores.17 An increase in submarine activity in November brought a request from the Navy for more Army air units at the Newfoundland Airport in order to afford greater protection for Allied shipping and to insure the safety of essential sea communications.18 By the first week of December 1941 the 49th Bombardment Squadron, with nine B-17B’s, was preparing to depart the United States for Newfoundland, and the AAF was attempting to obtain a small supply of depth bombs which were needed for attacks on submarines.19

Air defense preparations in Greenland were not so far advanced as those in Newfoundland. Surveys which were made during the spring and summer of 1941 had failed to disclose any site suitable for an airfield on the eastern coast, but a promising site was found on the southern tip of the island at Narsarssuak, about thirty-five miles northeast of Julianehaab.20 In west Greenland a suitable location for a staging field was found in the Holstenborg district, and top priority was given to the building of runways and air base facilities in order to speed delivery of aircraft to Great Britain.21 Plans were made to develop the Narsarssuak site into a major air base as rapidly as possible, the Secretary of War having directed in the spring that establishment of a Greenland air base be accelerated.22 Proposed sites for other military installations were investigated during the fall of 1941 by Col. Benjamin F. Giles, an Air Corps officer who had been designated to head the Greenland Base Command.23 The planned Army air garrisons for Greenland, approved by the War Department in October, comprised one heavy bombardment squadron, one interceptor pursuit squadron, an air base squadron, weather and communications detachments, and air service units totaling 921 officers and men.24 Only a few weather, communications, and aviation engineering troops had arrived by December 1941; tactical squadrons could not be sent until construction of airfields and housing had been completed. Two stations in the Army airways communications system were in operation

in Greenland by this time, and two companies of aviation engineers were hurriedly constructing the facilities necessary for air defense of Greenland.25

American defense preparations in Iceland were accorded a degree of urgency not given to those in Greenland, even though more than 25,000 British troops were protecting the island. On 5 July 1941 President Roosevelt, in oral orders to the Army Chief of Staff and the Chief of Naval Operations, directed that one Army pursuit squadron with the necessary maintenance and administrative detachments be sent to Iceland as soon as practicable. The 33rd Pursuit Squadron was immediately prepared for shipment, and on 25 July the air echelon, with thirty P-40’s and three primary training planes, boarded the carrier Wasp at Norfolk, Virginia. Two days later an air base squadron sailed from New York for Iceland, and American planes shortly were operating from the Reykjavik airdrome in southwestern Iceland. The air service contingent was augmented in November by 21 officers and 336 enlisted men from the First Air Force, comprising ordnance, weather aircraft warning, and matériel units.26 American ground forces were also arriving in Iceland, but complete relief of British forces was not expected to be accomplished before May 1942; until that time the defense of Iceland was the joint responsibility of all air, ground, and naval forces stationed there.

Prior to the outbreak of hostilities in December 1941, American forces in Iceland were operating under orders which stipulated that the approach of any Axis forces to within fifty miles of the island would be deemed “conclusive evidence of hostile intent” and would justify attack by the American defenders. The mission of Army aviation, operating under the Iceland Base commander included independent action against sea, land, and air objectives, support of land and naval forces in offensive and defensive operations, aerial reconnaissance and photographic operations, and transportation of supplies and personnel. The 33rd Pursuit Squadron was of course incapable of carrying out all phases of the mission, and plans were being made for shipment of a bombardment squadron, and observation squadron, and an additional pursuit squadron.27

Reinforcement was delayed both by the shortage of trained squadrons in the United States and by the lack of proper aviation facilities in Iceland. British forces had prepared two airfields for limited operations and had formed a coastal observation network of thirty-nine

posts, all provided with telephone communications. But new airfields, improvements in existing airfields, and large quantities of aircraft warning equipment were required to complete the basic defense of the island. For stations not immediately adjacent to seaports, the supply problem was extremely difficult; there were no railroads, and many roads were closed during the winter. Utilities such as electric power and water were not available in sufficient quantities to supply the needs of the armed forces. in spite of the necessarily slow development of facilities, the first Army air units gained valuable experience in operating with the Royal Air Force at the Reykjavik and Kaldadarnes airdromes. An alert system was in use twenty-four hours a day, and air operations were carried out in accordance with procedures tested and established by the British during two years of war against the Axis.28

In October, when weather conditions began to interfere seriously with the operation of Navy patrol bombers in Iceland, the Chief of the Army Air Forces directed that a heavy bombardment squadron and the necessary service troops be sent immediately to Iceland, prepared to operate in lieu of naval air forces in protection of shipping as well as to operate in defense of the island.29 The decision represented a great concession on the part of the AAF, for at that time the Air Force Combat Command had a total of only thirty-four heavy bombers which were not earmarked for overseas stations and the transfer of eight planes to Iceland would have left only twenty-six heavy bombers in the United States. The proposed move was not made because of the poor condition of runways and the lack of base facilities in Iceland.30 Transfer of a medium bombardment squadron, equipped with eighteen B-25B’s, was being held up for the same reasons, and the first week in December found the AAF seeking approval of an extensive program of air base construction for Iceland. A study of the situation indicated the desirability of sending a complete heavy bombardment group to the island for operation against surface and undersea craft in conjunction with the Navy and for protection of shipping in the North Atlantic. There was likewise need for two medium bombardment squadrons to collaborate in the work, especially prior to development of facilities for heavy bombers. Addition of a pursuit group and construction of an air base on the east coast of the island were regarded as essential to thorough defense operations, for German aircraft at that time could fly without too much

risk over the greater part of Iceland.31 But despite the recognized need for Army air units at all North Atlantic bases, only token forces were deployed in the area by 7 December 1941.

The Caribbean

The concept of far-flung air defense was receiving wide application in the Caribbean area, with new air bases, nests of antiaircraft guns, and aircraft warning outposts fringing the Caribbean Sea.* Distributed among the military fields and installations were 1,112 officers and 14,974 enlisted men of the AAF and approximately 137 pursuit planes, 77 bombers, 22 attack aircraft, and 9 observation planes. Combat effectiveness, however, was not assured by numerical strength, for a majority of the men were incompletely trained and most of the aircraft were obsolete. Partially trained forces were expected to complete their training while performing basic defense duties, but the shortage of modern aircraft and the necessity of erecting barracks and other base facilities acted as deterrents to the program. More significant than the number and status of troops deployed in the area were the broader aspects of air force organization and planning and the position of air units in relation to other forces in the Caribbean Defense Command. Under the guidance of Maj. Gen. Frank M. Andrews, the scattered Caribbean units had been welded into an integrated air force which was essentially a task force, complete within itself, capable of both independent and cooperative action, a commanded only by air officers.32

The organization of the Caribbean Air Force represented a marked structural advance over the force which previously had been depended upon for the air defense of the Panama Canal. Although military aviation had been a part of canal defenses since 1917, until late in 1939 Army air units, then organized under the 19th Wing, had occupied a subsidiary position in the Panama Canal Department. During the early months of 1940 the whole subject of canal air defense was reexamined by the War Department, and with Air Corps expansion the 19th Wing developed into the Panama Canal Department Air Force, which in turn provided a nucleus for the Caribbean Air Force in the spring of 1941.

The capabilities of modern aircraft, as demonstrated in the European war, led American military commanders in the Canal Zone to

* See maps, p. 300 and p. 543.

Construction of Alaskan Landing Field, August 1941

Construction at a Camp in Iceland, November 1941

P-26

P-35

the conclusion that an air assault on the locks and other vital installations would be the most likely form of attack by an enemy in the area. The importance of air defense was consequently heightened, although the mission of Army air forces in the Canal Zone remained unchanged. A Joint Board report in 1937 had specified the joint mission of Army and Navy forces in the Panama Canal Department as “protection of the Panama Canal in order that it may be maintained in continuous operating condition.” obviously for passage of the fleet. The Army mission was to protect the canal against sabotage and against attacks by air, land, and sea forces, while the Navy mission was to support the Army in defending the canal and to protect shipping in the coastal zones. Local defense plans gave Army aviation the responsibility of air defense of the canal, with the understanding that naval patrol planes would carry out distant reconnaissance, patrolling, reporting, and tracking. The two major tasks of the Army air component consisted of furnishing an offensive or striking force to destroy enemy vessels encountered and of furnishing a defensive force to combat air attacks. Similar missions were assumed by other Army air contingents as bases were established throughout the Caribbean and by the Caribbean Air Force upon its activation in May 1941.33

Of the several outlying sites in the eastern Caribbean, Puerto Rico presented the most advanced stage of development in air defenses by December 1941, primarily because preparations had begun early in 1939. The Air Corps had previously been unable to secure approval of an air base in Puerto Rico, for the War Department regarded such a development as purely a wartime measure. A site in the Punta Borinquen area was selected for a major air base, and seven sites were chosen for auxiliary airfields. In December 1939 the 27th Reconnaissance Squadron arrived from the United States to begin the air defense of Puerto Rico. One year later, approval had been granted for creation of a composite wing in Puerto Rico, to consist of an interceptor group, one heavy and one medium bombardment group, two air base groups, two reconnaissance squadrons, and one observation squadron. Cadres for some of the units were sent from the United States early in 1941, and by subdividing they furnished the skeleton forces needed for activation of other units. The 13th Composite Wing, under the command of Brig. Gen. Follett Bradley, became the initial unifying agency for military aviation in Puerto Rico, while a provisional air defense command was established to

direct the operation of antiaircraft artillery, aircraft warning services, passive defense measures, and interceptor aviation. The last element was conspicuous by its absence throughout most of 1941, but the plan for unified air defense was keeping pace with developments in the Zone of the Interior. The aircraft strength of the 13th Wing by the end of April 1941, consisting of only three A-17’s and twenty-one B-18A’s, was not sufficient to meet either defense or training needs of the 27th Reconnaissance Squadron, the 25th Bombardment Group (H), and the 40th Bombardment Group (M), which made up the tactical component of the wing. The Army air garrison in Puerto Rico was therefore not called upon at that time to assist in establishing air defense units on other island of the Caribbean.34

In Jamaica, Antigua, St. Lucia, British Guiana, and the Bahamas, Army engineers were constructing facilities at each base to permit operations by one heavy bombardment group and one long-range reconnaissance squadron. An airfield in Trinidad was being furnished with similar facilities, along with provisions for one interceptor pursuit group.35 Bermuda, while not in the Caribbean area, was related to both Caribbean and continental defense, and airfield construction on the leased site was being designed to accommodate one composite group of the AAF.36 Accommodations at the new bases did not necessarily determine the size of garrisons, for tactical units were not available in sufficient numbers to be stationed at all of the fields. The approved peacetime garrisons called for one heavy bombardment squadron and a group headquarters at Bermuda, an airways detachment at Jamaica, Antigua, St. Lucia, and British Guiana, and a composite wing of one heavy bombardment group, one pursuit group, and one reconnaissance squadron at Trinidad.37 Considerable importance was attached to early garrisoning of the Piarco airport at Trinidad. In the latter part of April 1941 a base force sailed from new York, while an air contingent of some 400 officers and enlisted men with six B-18A’s moved from the Canal Zone to Trinidad.38 In July other Caribbean bases began to receive garrisons, when airways detachments and infantry units were shipped from New York to British Guiana and St. Lucia. Similar forces were sent to Antigua in September and to Jamaica in the following month.39

Despite the attention given to new bases, the Canal Zone continued to be the focal point of Caribbean defenses. France Field on the Atlantic side of the Zone and Albrook Field on the Pacific side were

air bases of long standing, while a d permanent base, Howard Field, was nearing completion three miles from Albrook. Scattered throughout Panama were seven auxiliary airfields, two of which were ready for immediate use, and a number of emergency landing fields which did not require extensive improvements. By the first week of December 1941 a total of 183 planes, as opposed to an authorized strength of 396, were assigned to bases in the Canal Zone. At Albrook Field were 114 aircraft of all types, including 71 P-40’s, while France Field had 40 planes, most of them obsolete, and Howard Field had 20 aircraft, including 12 A-20A’s. Such outmoded types as the P-26 and the A-17 made up a large part of the strength; their value in protecting the canal was negligible.40 Of eight B-17’s, which comprised the heavy bombardment force of the entire Caribbean area, four had been sent to Trinidad and four were in Panama by November, but the growing crisis in the Far East resulted in a move to concentrate the planes in the Canal Zone by December. Tactical units defending the canal included the 6th and 9th Bombardment Groups (H), the 59th Bombardment Squadron (L), the 16th, 32nd, and 37th Pursuit Groups, the 7th and 44th Reconnaissance Squadrons, and the 39th Observation Squadron. Three air base groups, and air depot, and signal and ordnance units performed the necessary service functions in the Canal Zone.41

Steps toward coordination of defense efforts in the Caribbean area had been taken early in 1940. Joint Army and Navy war plans, recognizing the possibility of enemy action in the region, had defined the bounds of a Caribbean theater, and Army plans provided for designation of the commanding general of the Panama Canal Department as commanding general of the theater. In the spring of 1941 the plans were put into action with formation of the Caribbean Defense Command; organization of a single air force as a part of the command was a natural concomitant to the action. The defense command was divided into Panama, Puerto Rico, and Trinidad sectors, the commanders of which were responsible for defense of the respective areas and for training of all assigned personnel except those of the Caribbean Air Force. The air force, organized on a theater-wide basis subdivided into bomber, interceptor, and service commands, was charged with planning, training, and execution of plans for air operations and defense against air attack throughout the Caribbean. The basic principle of its organization was the concentration of force

under one command in order that the full weight of available air power could readily be thrown against an enemy at whatever point he might appear.

Operational planning in the Caribbean took on a new note of realism during the months just prior to American entry into the war. Joint plans for armed assistance to certain South and Central American republics, kin the event of attack by non-American state or by “fifth columnists,” provided for action by Caribbean defense forces and also troops in the United States. Essential features of the plan called for the occupation on forty-eight hours’ notice of strategic interior points by Caribbean-based troops transported by air, the prompt occupation of seaports by naval forces, and the reinforcement of these forces by Army expeditionary troops dispatched from the United States. It was clear that the security of the Panama Canal would be menaced by the successful overthrow of recognized governments in countries near the canal and the establishment of regimes opposed to the principles of Pan American solidarity. Although there was no occasion to invoke these plans, their existence gave the Caribbean Air Force a high priority in the delivery of transport planes from the United States and enabled Caribbean defense force to experiment with airborne operations in the fall of 1941. Following activation of an infantry airborne battalion at Howard Field and arrival of a parachute battalion from the United States, cooperative exercises were carried out by ground and air forces in the Canal Zone, and subsequent reassignment of the airborne units from the Panama Canal Department to the Caribbean Air Force for training purposes made possible a higher degree of coordination. Of the overseas departments of the Army, the Caribbean Defense Command was unique in the possession of airborne forces on the eve of hostilities.

Local planning for armed assistance to Latin-American republics served to emphasize the need for closer Army-Navy coordination in the Caribbean. A considerable body of evidence indicated that “voluntary cooperation” would not insure effective joint defense,, but the insistence of the Caribbean Defense commander upon unity of command was to no avail prior to American entry into the war. The subject of joint action came to the fore in mid-1941 when an increasing number of reports of Axis vessels in Caribbean waters led the local Navy commandant to request assistance from the Caribbean Air Force. By September the air force had been asked to assume 50

per cent of all search operations in the area. Total compliance would have completely disrupted the striking force which the bomber command was obligated to maintain in order to attack enemy naval craft or installations within its radius of action. Both naval and military forces were operating below their authorized strength, and regardless of desires for mutual assistance and plans to that end, the Caribbean area was sadly deficient in the matter of aerial overwater reconnaissance.

The vital importance of this phase of canal defense was revealed in an estimate of enemy capabilities prepared by the Caribbean Defense Command in the latter part of November 1941. Japan was regarded in respect to the canal itself as the primary potential enemy, and a carrier-based attack from the Pacific was considered “not an improbable feat.” Other possibilities were taken into account, but it was concluded that in any event the most important defensive measure was “increasing and thorough reconnaissance and observation of the air, sea, and land approaches to the Canal Zone.” Existing forces in the are were regarded as sufficient to repel any probable initial attack on the canal provided they were given timely warning of the approach of hostile forces. The inability of defending naval and military air forces to perform the required amount of reconnaissance and to provide the “timely warning” constituted perhaps the chief weakness in Caribbean defense immediately prior to American entry into the war. It was a weakness which was recognized by both Army and Navy commanders, their expressed hope lay in the postponement of attack by an enemy until the defending forces could achieve the proper degree of coordination and the necessary equipment for complete coverage of the vast sea frontiers.

The emergence of the air weapon as the predominant element of Caribbean defense was not unnatural in the light of the European war and the geography of the area. The experience of Great Britain and other countries at the hands of the Luftwaffe had affected the growth of American air power in general and the strengthening of overseas garrisons in particular. The climax of prewar air preparations in the Caribbean occurred in September with the elevation of General Andrews from his post as head of the air force to that of the Caribbean Defense Command, marking the first time an airman had ever commanded all Army forces in the area. The Caribbean Air Force, now under the command of Maj. Gen. Davenport Johnston, was not

adequately equipped by 7 December 1941 to carry out all of its responsibilities. Although approximately 165 P-40’s had arrived in the Caribbean, they were not furnished with the necessary devices to assure interception or to operate effectively at night. The pursuit aircraft were on the alert twenty-four hours a day, but only about 50 per cent of their practice missions resulted in interceptions. A mere handful of heavy bombers comprised the only long-range aircraft in the area. The absence of air bases on outlying islands in the Pacific left western approaches to the canal but poorly covered, and the plan to furnish armed assistance to Latin-American countries created further demands on the limited number of aircraft. But by virtue of its organization as an integrated force and its acquisition of base sites far to the east of the canal, the Caribbean Air Force was approaching a suitable stage of preparedness – at least for its task of defense against a European enemy.42

Alaska

The youngest and smallest overseas air force was located in Alaska, where some 2,200 officers and men of the AAF were stationed by the first week in December 1941.43 Aircraft and tactical units had not been sent to Alaska until construction of Elmendorf Field at Anchorage was well under way. When the first Air Corps representatives, consisting of one officer and two enlisted men, arrived for duty at Anchorage in July 1940, only preliminary work had started on the field; but by early 1941 a temporary hangar was ready for use and tactical units began to arrive from the United States. In the latter part of February the 23rd Air Base Group, the 18th Pursuit Squadron with twenty P-36’s in crates, and the headquarters squadron of the 28th Composite Group took up quarters at Elmendorf. These units were followed in March by the 73rd Bombardment Squadron (M) and the 36th Bombardment Squadron (H), equipped with a total of twelve B-18A’s.

Consolidation of the military air units occurred on 29 May with formation of the Air Filed Forces, Alaska Defense Command. The new organization was charged with training of Air Corps personnel, maintenance of aircraft, and planning and execution of Alaskan air defense. On 17 October the designation Air Field Forces was changed to Air Force, Alaska Defense Command.44 The Alaskan air force, more closely related to the Zone of the Interior than other overseas

air forces, depended upon a complicated chain of command. In order to communicate with officials in Washington it was necessary for the air force to direct its correspondence through the Alaska Defense Command, which forwarded the material to headquarters of the Western Defense Command at San Francisco; only from this point could the correspondence be sent directly to the War Department. The close attention given to Alaskan air needs by both the Alaska and the Western Defense Commands, however, tended to compensate for any delays encountered in the routing of requests.

The decision to station military air units in Alaska had not been made until after the outbreak of war in Europe, although the Air Corps for some years had advocated such a move. Once the threat to American security became clear, there was a general agreement as to the necessity for systematic air defense of Alaska. But determination of the position which military aviation would occupy in the total system of Alaskan defense required a considerable amount of discussion among the services, and several basic issues were not settled until the eve of hostilities. Brig. Gen. Simon B. Buckner, Jr., heading the Alaska Defense Command, sought approval of a program of strategically located airfields and adequate garrisons for the bases. It was estimated that any enemy assault on the territory would be primarily an air attack, which could be opposed only by air forces previously stationed in the area. In joint plans of the Army and Navy, however, Alaskan defense was essentially a function of the Navy, supported by air and ground forces at those points where coastal installations required protection from air raids. Little attention was originally given to the potentialities of long-range striking forces in opposing an enemy assault, although the Air Corps was convinced of the importance of all phases of military aviation in Alaskan defense. Because of the nature of the terrain and the lack of transportation facilities, ground forces were virtually tied to their stations, and local Army commanders felt that only string air forces and a system of well-developed airfields could assure the mobility needed to repulse a coordinated enemy attack.45 The practicability of air operations in Alaska had been demonstrated by both military and commercial aircraft, and a new AAF cold-weather experimental station at Ladd Field, Fairbanks, was preparing to conduct tests which would reveal better methods of equipping aircraft for arctic operations.

The plan for air defense, as worked out by the Alaska Defense

Command, provided for a group of advanced bases, a series of intermediate airfields, a chain of fields between Anchorage and the United States, and an extensive aircraft warning system. The first item provoked the greatest amount of discussion among the services responsible for protection of Alaska. The older theory of Alaskan defense had been centered around the Seward–Anchorage areas, supplemented by joint Army and Navy defense of naval installations at Kodiak Island; and control of the North Pacific was naturally regarded as a task of the Navy, operating from bases at Kodiak and Dutch Harbor. The latter base, on Unalaska Island in the Aleutians, constituted the westernmost installation in the area. Protection of Dutch Harbor was a function of Army air units, and since that protection could not be furnished without air bases in the vicinity, the Alaska Defense Command proposed to construct a field on Umnak Island, sixty-five miles west of Dutch Harbor. Naval authorities viewed the proposal as undesirable, for Umnak had no adequate harbor development and construction of the base would put an increased strain on sea communications at a time when shipping was at a premium.*

There was, however, a cogent reason for development of an airfield on Umnak, beyond considerations of immediate protection of Dutch Harbor. Such a base would increase the striking range of Army bombers, enabling them to command a radius of 400 miles greater than would be possible from such a point as Chignik, on the Alaska Peninsula. It was important that any hostile force be intercepted before it could launch an attack, and it was likewise important that enemy forces be prevented from establishing bases in the outer Aleutians. For both contingencies, the existence of an airfield and a long-range striking force in the Aleutians seemed to be necessary. The Aleutian Islands comprised steppingstones which could lead in two directions, and their offensive possibilities for American forces would be nullified by a lack of airfields. At the insistence of the Navy Department the Umnak proposal was referred to the Joint Board of the Army and Navy, and approval was given on 26 November 1941.46

The remainder of the air defense program met with little opposition. Airfield construction was proceeding under the direction of Army engineers and the Civil Aeronautics Administration, although in the colder areas of Alaska the work was impeded by arctic conditions. Heavy rainfall, particularly along the southern and western

* See maps, p. 305 and p. 463.

coast line, prevented uninterrupted work. Every advantage had been taken of the summer months, and by the fall of 1941 Elmendorf, Ladd, Kodiak, Yakutat, and Nome fields were capable of supporting tactical operations by at least one squadron each, while more than a dozen additional fields of various sizes were nearing completion. A detailed plan had been drawn up for aircraft warning installations, including radar detector stations and filter centers. The plan was approved on 3 December, but almost no equipment was available for use.47 Army airways communications personnel, who had arrived in the spring of 1941, were operating at four stations, despite difficulties imposed by peculiar radio atmospherics and the lack of adequate power.48

No additional air units were sent to Alaska prior to the opening of hostilities, and the inability of the single composite group to carry out assigned functions of Army aviation was chief cause of concern to commanding officers. In Alaska, as at other overseas bases which were within reach of reinforcement by air from the United States, the AAF adhered to the policy that the aviation complement of Army garrisons should be held to the minimum required to meet initially such emergencies as might arise. The policy was based upon the generally sound principle of concentration of force within the United States under plans to utilize the special mobility of the air weapon in case of attack upon any of our outposts. But the heads of both the Alaska and the Western Defense Commands, along with Lt. Col. Everett S. Davis, commanding officer of the air force, joined in urging that additional air units be sent to Alaska for permanent station. It was pointed out that an attack or threat was regarded as a possibility. On islands off Alaska Peninsula and along the north and west coasts of Alaska, numerous sites existed which might be used for hostile landings. With only a small amount of work, enemy forces might prepare sheltered bays and landing strips for use as temporary naval and air bases and it would be difficult for defenders to dislodge them. Commanders responsible for Alaskan defense felt that in an emergency air reinforcements from the United States, in all probability, would not arrive in time. Granted that reinforcements could reach Alaska in time, pilots and crewmen trained only in the United States would be unfamiliar with the Alaskan terrain and flying conditions, and the

resulting loss of life and equipment might be prohibitive. The heads of the Alaska and Western Defense Commands therefore maintained that the air defense of Alaska must be made by planes permanently stationed in the territory and by crewmen trained in the area.49

Headquarters of the AAF appreciated the urgency of the situation in Alaska, and remedial action was promised as soon as the necessary aircraft should become available.50 Early in November the Chief of the AAF directed that plans be made to send a complete bombardment group to Alaska, and studies were also undertaken to determine the requirements for accommodating a pursuit group in the same area.51 These moves had not advanced beyond the planning stage by 7 December 1941, and the aircraft strength in Alaska still consisted of twelve B-18A’s and twenty P-36’s. The 28th Composite Group, though undermanned and poorly equipped, had been trained in Alaskan flying, and every pilot had made several landings at each airfield then ready to receive planes.52 Numerous flights had been made for the purpose of aerial photography and mapping, and coastal patrols were being run from Seward to Point Barrow.53 Combat crews were ready for transition to more up-to-date planes, but the relatively low priority held by Alaska among the overseas garrisons precluded the assignment of any modern planes to the North Pacific area.54 The air force of the Alaska Defense Command was, in fact, the only overseas air force which did not possess a single up-to-date plane prior to the outbreak of hostilities. The necessity for Alaskan air defense was by this time clearly recognized, and\ decision required to implement that defense had been rendered.

Hawaii

Air defenses in the Territory of Hawaii were the result of more than twenty years’ development, and their status by 7 December 1941 was relatively imposing. A total of 754 officers and 6,706 enlisted men made up the personnel complement of the Hawaiian Air Force, which was concentrated on the island of Oahu. The force, commanded by Maj. Gen. Frederick L. Martin, was organized tactically into the 18th Bombardment Wing, with headquarters at Hickam Field, and the 14th Pursuit Wing, with headquarters at Wheeler Field. Units of the bombardment wing included the 5th and 11th Bombardment Groups (H), the 58th Bombardment Squadron (L), and the 86th Observation Squadron.55 The latter unit was stationed

at Bellows Field, a road distance of some twenty-eight miles from Hickam. The 15th and 18th Pursuit Groups, components of the pursuit wing, were stationed at Wheeler, although one squadron was in training at Haleiwa, a small field in the northern section of the island. Two air base groups, a transport squadron, maintenance companies, and service detachments made up the remainder of the air force.*

In addition to the major airfields on Oahu, emergency and auxiliary fields had been prepared on other islands of the Hawaiian group, including Kauai, Lanai, Hawaii, Maui, and Molokai.56 Of the 231 military aircraft assigned to the air force on 7 December, approximately half the number could be considered up-to-date models. Twelve B-17D’s, twelve A-20A’s, twelve P-40C’s, and eighty-seven P-40B’s comprised the more modern aircraft, while thirty-three B-18A’s, thirty-nine P-36A’s, fourteen P-26’s, and an assortment of observation, training, and attack planes made up the remainder of the total.57

The Hawaiian Air Force had existed as an integrated command only slightly more than one year. From the time of the arrival of the first tactical squadron in 1917 to 1931, when the military air component in the territory comprised some seven tactical squadrons and two service squadrons, the air units had been loosely attached to the Army’s Hawaiian Department without benefit of an air commander. In 1931 an important administrative step was taken in formation of the 18th Composite Wing, which provided the separate squadrons with an air headquarters. Expansion of the Air Corps brought about a need for further reorganization in Hawaii, and on 1 November 1940 the Hawaiian Air Force was activated and its bombardment and pursuit units were organized into separate wings. Although the air force remained under the command of the Hawaiian Department, it had acquired the integrated structure necessary for efficient operation.58

Since 1935 the War Department had given first priority to the Hawaiian Islands in the distribution of troops and munitions among overseas garrisons. But, upon the outbreak of war in Europe, the necessity for giving attention to bases in the North Atlantic and the Caribbean, together with the urgent demands of a vast program of expansion, had altered peacetime priorities; and not until early 1941 was it possible to send modern planes and additional antiaircraft artillery

* See map, p. 196.

to the Hawaiian Department.59 The aircraft strength at the beginning of 1941 consisted of 117 planes, all of them obsolescent or antiquated.60 In mid-February, thirty-one P-36’s, with pilots and crew chiefs, were placed aboard the carrier Enterprise at San Diego, California, and sent to the Hawaiian Islands. Modern pursuit planes were made available within the next two months, and by mid-April a total of fifty-five P-40’s had been transferred via carrier from the West Coast to Oahu, where they were flown off the deck to Army airfields.61

A decision to allocate B-17’s to the Hawaiian Air Force provoked a considerably greater amount of discussion and entailed for more intricate planning than did the transfer of the P-40’s. Heavy bombers could reach their destination only by flying, and no mass flight of heavy bombers had ever been made over the 2,400-mile stretch between the West Coast and Hawaii. In official quarters there was at first some hesitation to undertake such an operation for fear of public reaction in the event of failure.62 The need for an air striking force in Hawaii, however, seemed to justify the risks involved, and early in April the Fourth Air Force began to make preparations for ferrying twenty-one B-17’s to the Hawaiian Islands. The 19th Bombardment Group, under the command of Lt. Col. Eugene L. Eubank, was selected to fly the planes, and service tests were conducted on the aircraft before they were certified for the operation. Weather data and navigational problems were studied, while arrangements were made for assistance by the Navy Department, Pan American Airways, and commercial radio stations in San Francisco and Honolulu. The Navy stationed four guard vessels at 500-mile intervals along the path of the flight, and all naval vessels in the vicinity were asked to transmit weather information. The Navy also assisted in establishing communication facilities to insure the proper ground-air liaison in San Francisco and Honolulu; commercial airline officials in the same locations agreed to transmit weather forecasts and mad signals; and commercial radio stations in the two cities arranged to provide homing signals by broadcasting continuously during the flight. As a result of thorough preparations, the flight was accomplished without undue incident. On 13 May twenty-one B-17D’s took off from Hamilton Field, California, and on the next morning, after an average elapsed time of thirteen hours and ten minutes, the planes landed at Hickam Field within five minutes of the estimated time of

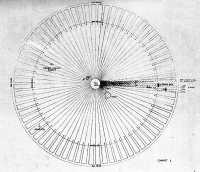

Search Sectors: A Plan for the Employment of Bombardment Aviation in the Defense of Oahu.

arrival. Members of the Hawaiian Air Force, who had never flown heavy bombers, began to receive intensive instructions from fifteen crew members who had made the flight, while the remainder of the 19th Bombardment Group sailed back to the mainland.63

The allocation of a greater number of heavy bombers to the Hawaiian Air Force than to any other overseas garrison in the spring of 1941 was an indication of a growing concern over the possibility of war in the Pacific. It was also a testimony to the importance of Hawaiian defense, an importance which stemmed both from the existence of Pearl Harbor naval base on Oahu and from the position of the Hawaiian Islands in continental and hemisphere defense. The duties of Army and Navy forces protecting the islands had been clearly defined in joint defense plans. The principal joint task assigned to forces permanently based in the territory was “to hold Oahu as a main outlying naval base.”64 In accordance with standard procedures established for American forces on the continent and overseas, the Army was to provide the mobile land and air forces required for direct defense of the island coast lines against attack, while the Navy was to conduct operations directed toward defeat of an enemy force in the vicinity of the coast and to support the Army in repelling attacks on coastal objectives. To accomplish its mission the Navy was charged with the provision and operation of “a system of offshore scouting and patrol to give timely warning of an attack, and in addition, forces to operate against enemy forces in the vicinity of the coast.”65 It thus became the responsibility of the Navy to maintain the long-range reconnaissance that would be required for advance notice of an approaching enemy, but to the Army fell the operation of an air warning system that would promptly alert all defense forces against specific attacks by air. Since such a division of responsibility called for close cooperation between the services, Army and navy commanders in Hawaii had agreed that if the threat of a hostile attack were sufficiently imminent to warrant joint action, each commander would “take such preliminary steps as are necessary to make available without delay to the other commander such proportion of the air forces at his disposal as the circumstances warrant.”66

These arrangements, it can easily be seen, were more theoretical than practical, more general than specific. The need for a thorough reconsideration of Hawaiian air defense led the War Department General Staff in July 1941 to order that the AAF make a study of

“the air situation in Hawaii.” The result was formation of a detailed plan for the employment of bombardment aviation in the islands. The plan, drawn up by the Hawaiian Air Force, regarded the two existing pursuit groups as adequate so long as they were maintained at full combat strength. Projected radar installations – six detector stations were in operation by December 1941 – were also considered to be reasonably sufficient. The heart of the plan lay in three major provisions: a complete and thorough air reconnaissance of the Hawaiian area during daylight; an attack force available on call to hit any target located as a result of the search; and, if the objective should be an aircraft carrier, attack against the target on the day before it could maneuver into position to launch its planes for an assault on Oahu. An early morning carrier attack was regarded as the most likely line of action to be taken by an enemy. The proposed plan for air defense pointed out that if the Hawaiian Air Force were to assume responsibility for its own reconnaissance, seventy-two B-17’s would be required to search daily the area within the circle of an 833-nautical-miles radius from Oahu, each plane covering a 5° sector. Since the required number of planes represented more heavy bombers than were then in use in the entire AAF, the plan obviously could not be put into operation. But the position of the Hawaiian Air Force had been made a matter of record; an aggressive defense, provided by long-range striking planes, was felt to be “the best and only means” of locating and attacking enemy carriers before they could come within launching distance of Oahu.67

The ability of the Hawaiian Air Force to perform its mission was affected in the fall of 1941 by a decision of the War Department to send reinforcements to the Philippines and by calls from the Navy Department for assistance in the defense of outlying islands in the Hawaiian area. The former gave the Hawaiian Air Force a lower priority in allocation of aircraft and required a diversion of some of its strength. The naval requests for assistance proved to be only a threat of diversion, but the total effect of these actions was to draw attention away from the immediate defense of Oahu. The Navy, which was charged with defense of certain outlying islands, found that because of a shortage of aircraft it would not be able to provide air forces for protection of Midway and Wake islands. late in October a Navy request for Army air garrisons met with the reply that essential installations must first be provided before any aircraft could

be stationed on the islands.68 The Navy was rapidly improving airfields at both locations, but service and maintenance facilities and housing were not then satisfactory for permanent garrisons. Nevertheless, the commander of the Hawaiian Department, Lt. Gen. Walter C. Short, on 28 November notified the War Department that two pursuit squadrons, each consisting of approximately 120 officers and men and 25 P-40’s, were ready for dispatch by carrier to Wake and Midway. The islands were to be reinforced also by Marine aircraft within a few days. When it was pointed out that the P-40’s would be frozen to the islands because of their inability to land on carriers, the Navy advised that final decision as to shipment of the planes should be held in abeyance.69

By this time, military and naval commanders in Hawaii had received warning of an impending break in American and Japanese relations, and forces in the islands had been placed on alert. The standard operating procedure of the Hawaiian Department outlined three alerts: the first required defense against acts of sabotage and uprising within the islands; the second called for security against attacks from hostile subsurface, surface, and air forces, in addition to defense against acts of sabotage; and the third provided for occupation of all field positions by all units, in preparation for the maximum defense of Oahu and Army installations on outlying islands in the Territory of Hawaii.70 Because a local estimate of the situation indicated that sabotage was more likely than outright attack by hostile forces, the Hawaiian Department ordered Alert No. 1 into operation and notified the War Department of its actions. Aircraft were concentrated in hangars or in open spaces near by, and extra guards were placed about the aircraft and military installations. Construction was started on protective fencing and floodlighting projects.71 Of the imminence of hostilities, there was little doubt; but it was generally felt that the most likely area of attack was in the Philippines.72 The eve of hostilities therefore found the Hawaiian Air Force continuing, as it had throughout the fall of 1941, to aid in rushing aerial reinforcements to the Philippines.

The Philippine Islands

American forces in the Philippine Islands were not ready for war by December 1941, but they were well aware of the threat of war and preparations were going forward in accordance with the plan to

hold the islands against enemy assault. Army air units, organized into the Far East Air Force under Maj. Gen. Lewis H. Brereton, had a total of some 8,000 officers and men and more than 300 aircraft, concentrated largely on the island of Luzon. Fewer than half of these aircraft were suitable for combat, and much of the equipment for air defense was still awaiting shipment from the United States.73 But the air force was equipped with thirty-five heavy bombers, more than any other Army air force, either on the continent or overseas. This fact was significant, for the Philippines had not always enjoyed top priority among American outposts. Indeed, for many years the Air Corps garrison there had been regarded as little more than a token force and had not been considered capable of meeting “serious contingencies.”74 As late as the spring of 1940, military aviation in the islands consisted of a mere handful of obsolete planes such as the P-26 and B-10, and during the summer of 1940 only three B-18’s were allotted to the Philippines. No additional aircraft could be spared at that time from units in the United States, and prospects of an early augmentation of pursuit strength were dimmed by a statement from the Air Corps that the twenty-eight P-26’s then assigned to the Philippine Department would have to suffice until late in 1941.75 Between the time of this statement and the outbreak of hostilities in the Pacific, however, War Department policy with regard to the Philippines underwent a drastic change, and the rapid expansion of aerial defenses in the islands represented one of the more important results of that change.

The possibility of American involvement in a Pacific war had been heightened in the fall of 1940 by formation of a pact between the Axis powers and Japan. Agreeing to support each other’s efforts in establishing and maintaining “a new order of things” in Europe and East Asia, the parties announced that they would assist one another “with all political, economic, and military means when one of the three contracting powers is attacked by a power at present not involved in the European war or in the Chinese-Japanese conflict.”76 The reference of course was obvious, and it carried a threat which President Roosevelt described in terms of the greatest danger faced by the nation since settlement of the continent.77

As part of a prompt attempt to strengthen the defenses of our most western outpost insofar as it was possible, the Chief of the Air Corps in October directed that forty-eight P-35’s, scheduled for shipment to

Sweden, be diverted to the Philippines. Late in November the 17th and 20th Pursuit Squadrons arrived from the United States and took up their station at Nichols Field on the outskirts of Manila.* In March 1941 the Hawaiian Department was ordered to ship eighteen B-18’s by transport to the Philippines, and the following month a merchant ship sailed from the United States for Manila bearing thirty-one P-40B’s. The arrival of reinforcements and the prospect of receiving additional aircraft necessitated the creation of a more modern air organization in the Philippines. The Army air garrison, which had hitherto been organized into the 4th Composite Group, consisted of the Headquarters and Headquarters Squadron, the 3rd Pursuit Squadron, and the two new pursuit squadrons at Nichols Field, and the 28th Bombardment and 2nd Observation Squadrons at Clark Field, approximately sixty miles north of Manila. On 6 May 1941 these units, along with the 20th Air Base Group and supporting units, were organized into the Philippine Department Air Force. This change proved to be only the first of a series of steps designed to bring about a more effective air force structure in the Philippines.78

The German attack on Russia in June 1941, together with mounting evidence of Japan’s intention to take advantage of the greater freedom of action resulting therefrom for the purpose of a conquest of southeast Asia, lent a new sense of urgency to all defensive preparations in the Pacific and particularly to those in the Philippines.79 Gen. Douglas MacArthur, military adviser to the Philippine government and former chief of staff of the U.S. Army, was recalled to active duty effective 26 July 1941 and placed in command of United States Army Forces in the Far East.. The Philippine Department Air Force, which became a part of the new command, was given a more flexible organization and a new designation on 4 August, when it became the Air Force, United States Army Forces in the Far East. The force by this time was able to put into the air one squadron of P-40B’s, two squadrons of P-35A’s, one squadron of P-26A’s, and two squadrons of B-18’s, but against even a mildly determined and ill-equipped foe, this show of air strength would have been sadly deficient. Japanese capabilities argued therefore for a radical upward revision in the apportionment of aircraft to the Philippines; moreover, the geographical position of the islands afforded the United States an opportunity, while providing for their greater security, to emphasize its opposition for further Japanese

* See maps, p. 202 and p. 221.

aggression in Asia. AAF Headquarters felt that a striking force of heavy bombers would be a necessary part of any attempt to guarantee the security of the Philippines, and there was a feeing among War Department officials that the presence of such a force would act “as a threat to keep Japan in line.” Consequently, and as a part of the over-all plan for maintaining a strategic defensive in the Pacific, the AAF now allocated to the Far East four heavy bombardment groups, to consist of 272 aircraft with 68 in reserve, and an additional two pursuit groups of 130 planes.80

Although the supply of aircraft in the United States did not permit immediate implementation of these plans, the necessary authority was received early in August when the Secretary for War approved a program for sending modern planes to the Philippines as soon as they became available. Arrangements were made for fifty P-40E’s to be sent directly from the factories and for twenty-eight P-40B’s, taken from operating units, to be shipped to the Philippines in September. Procurement of heavy bombers was more difficult, for in the summer of 1941 not a single group in the AAF was completely equipped with such planes. The 19th Bombardment Group, which had ferried the first B-17’s to Hawaii in May, was selected for permanent transfer to the Philippines, and the group was given priority in the assignment of B-17’s. So urgent was the need for heavy bombers in the Far East, however, that the AAF did not wait for the 19th Group to pioneer an air route to the Philippines. By the end fo July it had been decided that a provisional squadron from the Hawaiian Air Force would make the first flight of land-based bombers across the Pacific.

Preparations for the flight were made with utmost secrecy. Since information was lacking on airfields in Australian territory, two Army officers were flown by Navy plane from Honolulu in order to survey facilities at Rabaul in New Britain, at Port Moresby in new Guinea, and at Darwin in Australia. Runway construction on Midway and Wake islands was pushed by naval authorities, while picked crews from the Hawaiian Air Force underwent intensive training for the unprecedented flight. On the morning of 6 September the 14th Bombardment Squadron (H), consisting of nine B-17D’s and seventy-five crew members under the command of Maj. Emmett O’Donnell, Jr., took off from Hickam Field and headed for the first stop at Midway, 1,132 nautical miles distant. The first leg of the flight was completed after seven hours and ten minutes. The crews refueled and serviced

their own planes, staked them down for the night, and then retired for a few hours’ rest, with many of the men sleeping under the wings of the aircraft. At 0445 the next morning the planes took off for Wake Island, 1,035 miles away, where they arrived at 1120.

Since the next hop to Port Moresby involved flying over some of the Japanese mandated islands, the planes took off at midnight in order to pass over the territory unseen and thereby avoid any possible international incident. Climbing from their usual altitude of 8,000 feet to 26,000 feet, the bombers turned out all lights and maintained complete radio silence over the islands. Although they flew in a heavy rain and without communications, the B-17’s kept their assigned positions, and the 2,176-miles hop to Port Moresby was completed at noon on 8 September (local time). Australian officials were most hospitable to the crews, who remained at Port Moresby until the morning of 10 September. The next hop, 934 miles to Darwin, was covered in six and one-half hours, and early on the morning of 12 September the planes took off for Clark Field, near Manila. Upon encountering stormy weather, the B-17’s maneuvered into storm echelon, flying over water at an altitude of from 100 to 400 feet. By mid-afternoon the bombers reached Clark Field, where they landed safely in a blinding rain.81 Successful completion of the historic flight, despite primitive servicing facilities and incomplete weather data, offered reassuring proof that the Philippines could be reinforced by air.

General MacArthur, who regarded the air defense of the islands as one of the more serious deficiencies to be remedied, urged prompt action to provide additional aircraft and the equipment for an adequate aircraft warning service. A program of airfield development was already under way, and funds had been provided for a more extensive program. particularly welcome therefore was the news that his command was scheduled to receive before the end of November a light bombardment group equipped with fifty-two A-24’s and a heavy bombardment group with twenty-six B-s. These forces were the practical expression of a policy which, despite the many urgent demands on the AAF’s limited resources, gave to the Philippines the highest priority in the delivery of needed combat forces. indeed, out of an anticipated production in the United States of 220 heavy bombers by the end of February 1942, no less than 165 of the planes had been scheduled for delivery to the Philippines.82

Inasmuch as the aerial route via Midway and Wake was endangered

by the proximity of Japanese forces in the mandated islands, the AAF late in the summer of 1941 undertook to secure approval of a project for a South Pacific ferry route which would enable heavy bombers to reach the Philippines without passing near Japanese territory. During the previous two years, in fact, the Air Corps had attempted to acquire airfield facilities on a number of Pacific island steppingstones to the Far East. Without such bases, the Air Corps did not believe that full advantage could be taken of the potentialities and capabilities of long-range aircraft. The recommendations had been repeatedly turned down, however, and as late as February 1941 the War Department pointed out that it had no plans for movement of long-range Army aircraft to the Far East and that it could then visualize no need for such plans. It consequently seemed inadvisable to establish air bases which “might possibly fall into the hands of the enemy.” But within six months the situation was reversed. Not only did the War Department approve AAF plans for a South Pacific air route, but the project received top priority among those agencies charged with its development. After investigation of several possible routes, the AAF on 3 October forwarded its recommendations to the Chief of Staff, who immediately approved them and issued the necessary orders. The commanding general of the Hawaiian Department was placed in charge of the project, and the Navy and State departments pledged their aid in rapid completion of the undertaking.

Funds were promptly made available from defense aid appropriations, after a presidential letter of 3 October authorized the Secretary of War to “deliver aircraft to any territory subject to the jurisdiction of the United States, to any territory within the Western Hemisphere, to the Netherlands East Indies and Australia” and to construct the facilities needed for effecting such delivery. The State Department opened negotiations with the governments of the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Australia, the Netherlands, and the Free French in order to secure authority for the use of territory under their jurisdiction in the South Pacific. In Hawaii, after receipt of the War Department directive, General Short conferred with the commandant of the Fourteenth Naval District regarding the possibility of using fields under construction by the Navy at Palmyra and Samoa. Upon learning that the necessary facilities would not be completed at Samoa prior to 1 May or at Palmyra prior to 1 August 1942, General Short dispatched survey parties to investigate the possibility of providing minimum

facilities on Christmas and Canton islands, as well as in the Fiji Islands, New Caledonia, and Australia, by 15 January 1942.* It developed that the Navy could not offer assistance in construction until after completion of its own projects; the Hawaiian Department therefore was dependent upon whatever shipping and construction forces the Army could provide.

Results of initial investigations showed that at least one 5,000-foot runway in the direction of the prevailing wind could be prepared by 15 January 1942 at four sites: Christmas, Canton, Suva in the Fiji Islands, and Townsville on the east coast of Australia. By the first week in November the required diplomatic clearances had been received, along with assurances of cooperation from the several governments. In New Caledonia, where Australian forces were making defense preparations with the permission of the Free French, representatives of the Hawaiian Department negotiated with Australian authorities for improvement of airfields which could be used on the South Pacific route. This action resulted in provision of the necessary staging point between the Fiji Islands and the continent of Australia. Responsibility for development of the route from Australia to the Philippines was vested on 27 October in the commanding general of U.S. Army Forces in the Far East. General MacArthur had already initiated surveys of air facilities along that portion of the route and had established contacts with the senior British and Netherlands East Indies authorities. The Hawaiian Department commander continued to direct the development of the ferry route east of Australia. Chartering all the available tugs and barges in the vicinity of Oahu, Army engineers moved construction equipment, personnel, and their own water supply to Canton and Christmas, while the Hawaiian Department secured the services of a commercial engineering company for other points along the route. New Zealand officials, who had agreed to improve an airfield at Nandi in the Fiji Islands, made available all the equipment they could gather for the project.83

Pending completion of the South Pacific route, heavy bombers destined for the Philippines continued to use the route via Midway and Wake. The presence of Japanese air units in the Caroline and Marshall islands constituted a threat both to the Midway and Wake bases and to American aircraft in flight; but defending naval forces were ordered to take special precautions at the two bases, and heavy bomber crews

* See map, p. p. 429.

were instructed to take evasive action in order to avoid contact with Japanese air units.84 By the middle of October, General MacArthur had chartered two ships to transport aviation fuel to Rabaul, Port Moresby, and Darwin, and arrangements had been made for further shipment of fuel to these points from the United States. Since Wake and Midway still had sufficient supplies o fuel for ferrying purposes, the route was ready for more flights of heavy bombers. The 19th Group at Hamilton Field, California, was alerted on 16 October for its flight to the Philippines. Although depot overhaul of the twenty-six B-17’s delayed the departure of some of the planes, by the morning of 22 October the last of the aircraft had completed the flight to Hickam Field. Here the group was divided into several flights, since not all of the staging points were capable of accommodating twenty-six bombers at one time. The first flight took off from Hickam Field on 22 October. The entire movement was plagued by unfavorable weather and engine trouble, but within one week the first eight planes arrived at their final destination.85 By 6 November twenty-five B-17’s of the 19th Group had landed at Clark Field; and the final plane, grounded at Darwin because of engine changes and weather, soon arrived safely.86