Chapter 15: The AAF in the Battle of the Atlantic

While undertaking to meet the emergency demands of the Philippines, Hawaii, Java, India, China, Australia, the South Pacific, Alaska, and Panama, not to mention other requirements of hemisphere defense, the AAF had been forced to deal with still another emergency problem in the Atlantic. The Germans fully appreciated the fact that American participation in the European war would depend for its success on the free and rapid movement of supply. Consequently, with the entry of the United States into active warfare against the Axis, it became a key point in German strategy to extend into American waters the counterblockade already undertaken by the U-boat fleet in the eastern and northern Atlantic. Except for a few planes which through the latter part of 1941 cooperated with the Navy in patrol of the waters off Newfoundland, the air forces of the U.S. Army had received neither responsibility for antisubmarine warfare nor training in its techniques. But they found themselves immediately after Pearl Harbor committed extensively to antisubmarine patrol for want of other forces which were both available and competent for the task.

That the Germans would move their U-boats into American coastal waters as soon as practicable after the formal entry of the United States into the war was implicit in the military situation as it developed from 1939 to 1941. The U-boat fleet was the only weapon with which Germany could implement a counterblockade. And since 1939 the Germans had been operating against British and neutral shipping at every opportunity in a campaign which, after the fall of France, was greatly facilitated by the construction of five operating bases on the Bay of Biscay. In the beginning of the war the submarines

had concentrated on the waters adjacent to the British Isles. Then, when British countermeasures made those areas too dangerous, they had moved out into the convoy lanes. As air antisubmarine patrol became more effective (in the summer of 1941, nearly one-third of the damaging attacks against submarines were credited to aircraft),1 the U-boats had moved still farther afield, extending their activity westward to 49° and as far south as Africa. By November, submarine activity off Newfoundland had brought from Adm. Harold R. Stark, Chief of Naval Operations, a request that the number of Army planes stationed at the Newfoundland Airport be increased to the full extent permitted by available facilities.2 And from Newfoundland it was but a relatively short distance to the coastal frontiers of the United States itself.

Indeed, the only surprising thing about the appearance of the enemy in U.S. coastal waters was that it took the U-boats nearly a month to become active there after our entry into the war. Adm. Karl Doenitz, who more than any one else in the German High Command was in a position to know the submarine situation, has since explained this delay by the fact that the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor came as a surprise to Germany’s political and military leaders. Hitherto, U-boat commanders had been restrained for political reasons from operating in American waters; and when the declaration of war removed those restraints, no submarines were immediately available for operations in the American coastal area. In December it proved possible to send out only six equipped for this purpose.3

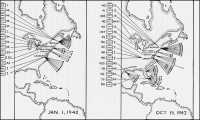

When they came, however, the U-boats struck with deadly effect. Beginning on 31 December, both Army and Navy sources began to report the presence of enemy submarines in American waters. On 7 January, COMINCH (Commander in Chief, U.S. Navy) reported that a fleet of U-boats was believed to be proceeding southward from the Newfoundland coast for an objective as yet unknown. The objective became quite apparent when, on 11 January, the enemy sank the SS Cyclops off Nova Scotia and torpedoed the tanker Norness three days later off Long Island. These sinkings head the tragically long list of similar losses in the coastal waters which served to bring home to the American public the grim realities of total war. The situation rapidly grew desperate. During the seventy-six days following the sinking of the Norness, fifty-nine ships, amounting to a total of over 350,000 gross tons, went down in the Eastern Sea Frontier. Nor did

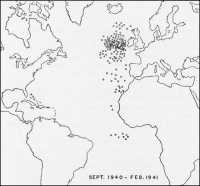

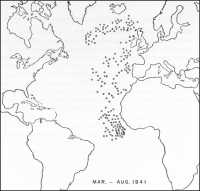

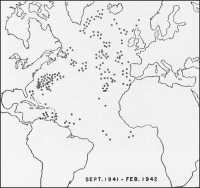

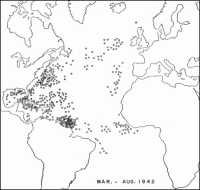

Sinkings of Merchant Vessels, September 1940–August 1942

Sinkings of Merchant Vessels, March–August 1941

Sinkings of Merchant Vessels, September 1941–February 1942

Sinkings of Merchant Vessels, March–August 1942

the German submarines confine their activity to that area. By February they were operating in the Gulf Sea Frontier where, during the ensuing two months, they accounted for eight merchant vessels. More alarming than this relatively light attack in the Gulf was the fact that by February a number of submarines had found excellent hunting in the Caribbean, especially in the waters off Aruba, Curacao, and Trinidad; during February and March they sank a total of forty-two merchant vessels in the Caribbean Sea Frontier.4 In short, enemy submarines hunted with relative impunity along the American coasts and with such success that they threatened the entire U.S. strategy in the Atlantic.

One of the more remarkable facts about the war was the well-nigh complete state of unreadiness in which this emergency caught the nation. Although the German submarine campaign in World War I lingered in the memory of Americans as a chief factor in our involvement in that struggle, and although for two years past a second German campaign had given repeated warning that the submarine again would be relied upon chiefly to offset the weight of American resources, when war came no master plan existed for coping with the danger. It is true that we had extended our bases eastward to Iceland with a view partly to the patrol of waters through which our shipping must pass, and that in this effort the maintenance of air patrols had been a primary consideration. But seemingly no one had seen fit to develop comprehensive plans and forces specially designed to counter the U-boat threat. As a result, the American war effort was to be challenged until September 1942 by deadly assaults on coastwise shipping, and not until the following summer would we be free of the fear that Germany might effectively cut the line of supply which supported our own and our allies’ operations in European and Mediterranean theaters.

Viewed broadly and from the vantage point provided by the lapse of time, it would appear that the situation required the immediate drafting of an over-all plan which viewed the Atlantic as a distinct theater of operations and brought together under a single directing agency all available resources to combat the submarine. In fact, such a proposal was ultimately made, and as the menace grew, vigorous efforts were expended to secure agreement at least on a plan to consolidate available air weapons in one command created specifically for the purpose of antisubmarine warfare and possessed of a strategic

mobility comparable to that enjoyed by the U-boat command itself.5 But all such efforts foundered on the rocks of inter-service controversy. The story of the antisubmarine air effort becomes, therefore, in no small part a story of jurisdictional and doctrinal debate punctuated by a series of compromises ending in a final compromise by which AAF forces withdrew from antisubmarine operations on the understanding that the Navy would relinquish all claim to control of long-range air striking forces operating from land bases.

It is not the purpose of this chapter to provide a full narrative of AAF antisubmarine activity. The bulk of that story falls chronologically outside the limits of this volume. It is necessary here, however, to consider the emergency problem which confronted the AAF on the outbreak of hostilities and the developments which led to the creation of the Army Air Forces Antisubmarine Command in October 1942. The operations of that command and the controversy which overshadowed its brief existence – extending from the fall of 1942 through the summer of 1943 – will receive separate treatment in the following volume.

The Question of Responsibility

Since the early development of military aviation in the United States, the Army and the Navy had differed on certain points regarding its control. With regard to land-based aviation engaged in seaward patrol, each service took a logical enough position. To the Army, land-based aircraft whether operating over land or water should be its responsibility. To the Navy, it seemed equally natural that operations over water against seaborne targets should be a naval responsibility. But since the air constituted a medium which extended over both land and water, arguments concerning its control could drift more or less at will for so long a time as national policy insisted on regarding the air arm as subordinate to either the Army or the Navy. It thus became a question that would have to be answered arbitrarily by some competent authority.

As early as 1920 it had been recognized that, in providing an air arm for both services, there lay a serious danger of duplicating installations and equipment. In that year Congress, accordingly, had determined that the Army air arm should have responsibility for all aerial operations from land bases and that to naval aviation belonged all air activity attached to the fleet, including the maintenance of such shore

installations as were necessary for operation, experimentation, and training connected with the fleet. This legislation provided the basis for the two air arms, but left undefined the responsibility in cases where joint action might become necessary.6

After 1935 the controlling statement of policy on such points was provided by Joint Action of the Army and Navy, an agreement which sought to clarify the relationship between the two services but which was marked at the same time, as previously noted, by ambiguity on certain crucial questions.* By its provisions, the Navy held responsibility for all inshore and offshore patrol for the purpose of protecting shipping and defending the coastal frontiers, whereas the Army held primary responsibility for defense of the coast itself. Army aircraft might, however, temporarily execute Navy functions in support of or in lieu of Navy forces; and, conversely, Navy aircraft might be called upon to support Army operations. In neither case should any restriction be placed by one service on the freedom of the other to use its power against the enemy should the need arise. Each service was declared responsible for providing the aircraft required for the proper performance of its primary function – in the Army’s case, the conduct of air operations over land and such air operations over the sea as were incident to the accomplishment of Army functions; in the case of the Navy, conduct of operations over the sea and such air operations over the land as were incident to the accomplishment of Navy functions.7 All of which left the responsibility for the conduct of seaward patrols and the protection of shipping definitely up to the Navy.

But this formal agreement did not preclude further discussion. There remained, in particular, a question of command. It was still an open question whether the Navy should control all air operations in coastal defense or whether it should control only those operations specifically in support of the fleet. Naval spokesmen claimed that unity of command should be vested in whichever service held paramount importance in any given situation. Then, assuming that naval preeminence existed in coastal defense, they claimed that unity of command in such operations should rest with the Navy. The Army, sensing a train of thought which might prove ruinous to its control of air forces, raised its voice in protest. The assumption of naval preeminence in coastal defense, it declared unsound. In some situations

* See above, p. 68.

land-based bombers might well be the principal arm employed. Furthermore, since most situations in which the Navy would be called upon for coastal defense operations would be ones in which the GHQ Air Force would also be involved as a striking force, the Navy would, according to its own argument, gain control of Army air forces in any tactical situation then considered likely to develop. This, the Army felt, might lead ultimately to Navy control of all air forces. As late as December 1941 the problem was still under debate; but unity of command in defense of the eastern coast, as far as joint air action was concerned, for practical purposes was vested in the commander of the North Atlantic Naval Coastal Frontier (NANCF).8

The Navy, then, at the outbreak of war was responsible for the protection of coastwise shipping and for the conduct of offshore patrol. In other words, the responsibility for the development of antisubmarine defenses lay with the Navy. The Army air arm, on the other hand, was obliged to act in support of or in lieu of naval forces should it be called upon to do so, that is to say, it had an emergency responsibility. In addition, Joint Action had explicitly stated that, regardless of the presence or absence of the fleet, the GHQ Air Force retained the responsibility for reconnaissance essential to its own combat efficiency as a striking force. Prior to 1939, however, Army aviation had been restricted from proceeding more than 100 miles beyond the shore line. There remains some question regarding the precise origin of this restriction, but the evidence indicates that it came initially from the Navy and was imposed in accordance with an agreement between the Chief of Naval Operations and the Chief of Staff, U.S. Army. Joint exercises held in 1939 for the purpose of Army-Navy training had occasioned a strong protest on the part of the Army air commanders concerned, who argued that it was impossible to maintain the navigational efficiency of their units without flights beyond the 100-mile limit. It was accordingly agreed that longer flights might be undertaken provided special arrangements were in each instance made “well in advance.” Not only was this an administratively awkward arrangement calculated to discourage the development of any extensive training program, but the Air Corps thereafter became increasingly preoccupied with the many-sided problems of a gigantic program of expansion centering on the mission of strategic bombardment. December 1941 thus found those AAF

units best equipped for antisubmarine operations trained almost exclusively in the performance of their primary function of bombardment rather than in a secondary, emergency duty of antisubmarine patrol.9

More serious was the inability of the Navy to meet a crisis falling in an area of primary responsibility. Whether because of its traditional concern for the problems of the Pacific or for other reasons, the crisis of December 1941 found the Navy unable to perform the offshore patrol necessary in order to cope effectively with the submarines. The commander of the North Atlantic Naval Coastal Frontier (in February 1942 replaced by Eastern Sea Frontier), on whom fell the immediate responsibility for countering the submarine menace, reported that he had at his disposal on 22 December 1941, after other demands on his resources had been met, a force of some twenty surface vessels capable of taking limited action against submarines. This force he regarded as woefully inadequate for its task, since there was “not a vessel available that an enemy submarine could not outdistance when operating on the surface. “In most cases,” he added, “the guns of these vessels would be outranged by those of the submarine.”10 Nor was it possible to augment these forces to any appreciable extent before May 1942. Repeated and urgent requests for destroyers and escort vessels were denied by COMINCH on the ground that equally imperative needs existed elsewhere.11 This inadequacy of surface forces naturally threw a heavier immediate burden upon available air resources, but strength in naval aircraft at hand for antisubmarine patrol proved equally insufficient. Of approximately 100 planes at the disposal of the NANCF commander on the outbreak of war, the great majority were trainers, scouts, or transport types, unsuited for the task at hand. By the end of January the situation had improved slightly, though not in the category of long-range patrol. “There are,” the NANCF commander reported to COMINCH on 14 January 1942, “no effective planes attached to the Frontier ... capable of maintaining long-range seaward patrols.” In reply to his urgent request for at least one squadron of patrol planes, he was told that additional allocations depended on future production.12 Here, as elsewhere in these early days of 1942, the demands made upon all services for men and equipment were great but the supply small.

So it was that the burden of antisubmarine patrol fell heavily on

the Army Air Forces during December 1941 and the early months of

1942. Although neither trained nor equipped specifically for the purpose, Army units possessed aircraft whose range generally exceeded that of available Navy planes. As soon as the news of the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor arrived, the NANCF commander requested the commanding general of the Eastern Defense Command to undertake offshore patrols with all available aircraft. Accordingly, on the afternoon of 8 December 1941, units of the I Bomber Command began flights over the ocean to the limit of their range.13

But it was a motley array of planes that I Bomber Command assembled in December to meet the submarine threat. At virtually the same time that it was called upon to undertake overwater patrol duties, it was stripped of the best-trained of its tactical units for missions on the West Coast * and for overseas assignment. Every available Army plane in the First Air Force capable of carrying a bomb load was drafted to augment what was left of I Bomber Command. As a result of these frantic efforts, approximately 100 aircraft of various two-engine types were assembled and placed at the disposal of the naval commander. To this force, likened by one observer to Joffre’s taxicab army of 1914, the I Air Support Command added substantial aid in the way of reconnaissance.14

By the middle of January 1942, this Army patrol had gained a little in strength and regularity of operation. The I Bomber Command was by that time maintaining patrols at the rate of two flights each day from Westover Field, Massachusetts, Mitchel Field, New York, and Langley Field, Virginia, and was in the process of inaugurating similar missions from Bangor, Maine. These flights, averaging three planes each, extended, weather permitting and according to the type of plane, to a maximum distance of 600 miles to sea. The longer distances were covered only by the few B-17’s operating from Langley Field, seldom more than nine of which were in commission. In addition to the aircraft of I Bomber Command, I Air Support Command operated patrols during daylight hours in single-engine observation planes extending about forty miles offshore from Portland, Maine, to Wilmington, North Carolina. These planes were not armed, nor did they carry sufficient fuel for more than two or three hours’ flying, and not more than ten of them were maintained in the air along the

* See above, Chapter 8.

coast at any one time. On the whole, however, it was a creditable effort, considered as an emergency measure. By the end of January, I Bomber Command aircraft available for antisubmarine duty numbered a total of 119. Only forty-six of the aircraft could be considered in commission, but of this effective strength, nine were B-17’s capable of long-range patrol, and the rest were B-18’s and B-25’s,15 both types capable of covering extensive stretches of the threatened sea lanes.

Even so, Army forces were themselves seriously inadequate. In addition to the insufficient number of AAF forces available, Army units began antisubmarine operations under serious handicaps of organization, training, and equipment. Hunting submarines was a highly specialized task, as all concerned found out during the next few months. Yet little had been done prior to the outbreak of hostilities to train and equip Army units for work of this sort or to establish a system of joint Army-Navy control. Some steps, it is true, had been taken to provide the means of cooperation between the services, with the result that a joint control and information center was ready for operation at New York four days after the opening of hostilities. Fortunately, the delay of nearly a month in the enemy’s invasion of American waters gave the I Bomber Command time to organize some sort of wire communication service to all its bases, and to establish an intelligence system through which information could be relayed from headquarters to squadron operations rooms. But to the end of January the problem of transmitting intelligence remained a vexing one.16

In addition to the fact that most of the Army air units involved in the antisubmarine war were still in a training status, those best trained having been taken away for service in the west, they brought to their task equipment and experience conditioned almost entirely by the requirements of ordinary bombardment, which had little in common with antisubmarine attack. It is hardly surprising, then, that Army planes at first flew in search of U-boats armed with demolition bombs instead of depth bombs and manned by crews who were ill trained in naval identification or in the techniques of attacking submarine targets. Moreover, the aircraft themselves, although intrinsically better suited to this type of operation than most of the available Navy planes, nevertheless fell far short of maximum efficiency in antisubmarine patrol. All, with the exception of the few B-17’s, possessed

medium range only, and were relatively limited in their carrying capacity. And all as yet lacked special detection equipment.17

This, then, was the status of the air defenses which the United States could bring to bear against the enemy at the opening of a most critical phase of that costly and crucial battle of Atlantic shipping and supply. It was an inadequate effort, albeit the best that could be mounted in the existing circumstances. The explanation lies partly in the general state of American military preparedness existing prior to December 1941. The emergency in the eastern coastal waters was in a sense but one of several desperate situations which, taken together, stretched the resources of the U.S. armed forces in those dark days almost to the breaking point. But the weakness of the antisubmarine forces can be explained only in part by mere lack of men and equipment. It must be explained also in terms of a lack of the right kinds of equipment and of properly trained men – which, in turn, points unavoidably to faulty planning in the field of coastal defense during the years before the war.

But the opportunities of those years were now gone. The immediate question was what steps in addition to the first emergency measures should be taken to cope with the submarine attack. That question resolved itself into two parts: (1) what defenses could be provided on a continuing emergency basis; and (2) what systematic approach could be made to the entire problem.

In considering the contribution that could be made by the AAF to the solution of the initial problem, it must be borne in mind that there were many calls for planes but few planes in these first days of the war. At the very outset, reinforcement of the Philippines had been given the highest priority, and only by repossession of LB-30’s from the British had it been possible to get out to the Netherlands East Indies the meager force which after sustaining heavy losses fell back on Australia. The demands of Australian defense itself outstripped the equipment salvaged from the Java operations. It had been necessary to send help to Hawaii. Growing concern for the security of the South Pacific, of Alaska, and of the Panama Canal prompted additional demands. The requirements of air transport placed still another premium on the very planes which because of their range were best suited to antisubmarine patrol. Nor was it possible while meeting these emergency calls to overlook the urgent requirements of an expanding training program which at the level of unit training demanded

combat planes.* Little wonder that General Arnold, faced with the problem of parceling out inadequate resources, was able to make available for antisubmarine operations only limited forces.

Early Antisubmarine Operations

Within the limits imposed by the general emergency, the operational record of those AAF units – principally of the I Bomber Command – which participated in the antisubmarine war was on the whole very creditable. Life in the I Bomber Command moved at a hectic pace during the early months of war. The entire command had to be reorganized. Having been relieved during December and January of all but one of its bombardment groups (the 2nd), it had in the first two months of 1942 to assimilate two new bombardment groups (the 45th and the 13th) and two reconnaissance squadrons (the 3rd and 92nd).18 These units were for the most part as yet untrained even in the normal techniques of bombardment, to say nothing of the special tactics of antisubmarine warfare. Thus the command was faced with the double problem of reorienting the training of its units and adapting all its equipment to meet the requirements of its enlarged mission. Moreover, most of the new techniques had to be learned through actual experience; and, owing to the urgent need for antisubmarine patrols, the air units were forced to accomplish their training in the course of operational missions.19

Though even more understaffed than most organizations in those days, I Bomber Command headquarters, under the command of Brig. Gen. A. N. Krogstad, attacked these complex tasks with resourcefulness and vigor. On 12 December, General Krogstad set up an advance echelon at New York City to conduct tactical operations in conjunction with the NANCF, and this detachment was followed shortly by the entire headquarters staff. On 24 January the system of joint defense was extended by the establishment of a liaison office with the Sixth Naval District at Charleston, South Carolina. The 66th Observation

*As evidence of a continuing difficulty in reconciling the demand and the supply of equipment, it may be further noted that the emergency call from the Middle East in June was met by diversion of the Halverson detachment and the transfer of virtually all heavy bombers from India, that the 43rd Bombardment Group (H) which had reached Australia in March did not receive its planes until September, that the Eighth Air Force began operations with only one heavy bomber group, and that the subsequent requirements of the North African operation served to keep the combat strength of the Eighth in heavy bombers at no more than six groups until May 1943.

Group of the I Air Support Command with a few B-18’s was placed under the operational control of this office in order to reinforce naval patrol in that area.20

It soon became evident that successful warfare against U-boats demanded improved methods of joint control so that both air and surface forces might proceed to the scene of a U-boat sighting with the least possible delay. Here the British were able to offer valuable advice based on the already considerable experience gained by RAF Coastal Command in joint operations with the Royal Navy. With the help of RAF officers sent to America at the request of the Assistant Chief of Air Staff, Intelligence for the purpose of giving aid and counsel to the new antisubmarine force, steps were taken to make the joint control room in New York City truly a nerve center for joint action.21

Naturally enough, this extreme activity on shore was not at once reflected in correspondingly improved operations at sea. Handicaps involving training and equipment could not be overcome immediately. In fact, they German submarines ran little risk from aerial attack during January and February of 1942. Although operational hours flown by Army planes in the Eastern Sea Frontier amounted to almost 8,000, only four attacks were made, none of which appears to have resulted in damage to the target. By the end of March the situation had improved perceptibly. The U-boats, it is true, continued in steadily increasing numbers to exact a mounting toll of merchant shipping. But they also were meeting rapidly stiffening opposition. I Bomber Command planes flew almost as many hours in March as they had in the previous two months put together.22 They still made relatively few attacks, and those they made left much to be desired. Yet this expanded air patrol, by forcing the enemy craft to remain submerged for increasing lengths of time, curtailed the freedom with which they had operated hitherto. It is also worth noticing that a few Army planes (four to be exact) had begun to carry radar equipment. More rapid increase in the use of this critically important equipment was prevented by a shortage both of new sets and of spare parts for the few old ones available. And much work remained to be done before the potentialities of radar for antisubmarine purposes could be realized.23

In March, too, the Civil Air Patrol began offshore flights with the aircraft of its newly created Coastal Patrol. These civilian aircraft,

ranging from light single-engine to twin-engine types, as yet carried no bombs, and for the most part were unable to fly patrols of any great distance; but they managed nevertheless to relieve the Army units, especially those of the I Air Support Command, of some of the routine reconnaissance flying. They operated under the guidance of that command, which in turn served under the operational control of the I Bomber Command.24

On 26 March 1942, an agreement was reached between the Army and Navy which clarified for the time being the relationship of both these Army air commands to the naval command. Heretofore the Army units had been operating under the control of the commander of the Eastern Sea Frontier, but the system rested on grounds outlined only very generally in joint Action and of recent months rendered soft and untrustworthy by prolonged debate. There had even been talk of “mutual cooperation” rather than “unity of command.” Some firm decision on the matter was therefore essential to efficient joint operations. It finally came in a message sent by the joint Chiefs of Staff to the commanding generals of all defense commands which unequivocally vested jurisdiction in the sea frontier commanders over naval forces allocated thereto and all Army air units engaged in operations over the sea for the protection of shipping and against enemy seaborne activities. Lt. Gen. Hugh A. Drum, commanding general of the Eastern Defense Command, promptly made available to the commander of the Eastern Sea Frontier all units of I Bomber Command, I Air Support Command, and the Civil Air Patrol, with the exception of three bombardment and four observation squadrons which were held as operational training units for the training of personnel in sea search.25

Generally speaking, the problem facing the AAF antisubmarine force had by the end of March assumed a more or less distinct outline. The I Bomber Command had made progress toward adjustment to the tactical situation into which it had been so suddenly thrust, but Brig. Gen. Westside T. Larson, who on 7 March had succeeded General Krogstad in command of the organization, was able to point out several impediments remaining in its path. Shortages in personnel and equipment, ineffective telephone and radio communication systems, a joint control room that, despite efforts made to improve it, still proved unsatisfactory – these were some of the difficulties he saw still to be overcome. In addition, he pointed urgently to the need for

AAF Antisubmarine Operations

operating bases south of Langley Field and for increased mobility on the part of the units under his command in order that advantage might be taken of a wider operating area.26

Any doubts regarding the necessity for extending the antisubmarine activity of the AAF and for increasing the mobility of its units were dispelled during the next two months by the Germans themselves who began rapidly to shift the emphasis of their attack toward the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean areas. This move on the part of the enemy found American defenses again unprepared, and the shift in operating area was accompanied by a sharp rise in the number of merchant ships lost in the coastal waters. In April, twenty-three ships were lost in the Eastern Sea Frontier, as compared to two in the Gulf Sea Frontier. In May, the number lost to submarine action in the former dropped to five, while the corresponding figure for the latter rose to forty-one. This total of forty-six merchant vessels lost during the month represents the high point in the U-boat offensive in the two home sea frontiers.27

In answer to an urgent request from the commander of the Gulf Sea Frontier for air reinforcement, a detachment of twenty B-18’s was sent south; and shortly thereafter, on 26 May, Maj. Gen. Follett Bradley, commanding general of the First Air Force, set up the Gulf Task Force of the I Bomber Command. This new organization was composed initially of the detachment of B-18’s mentioned above, together with two observation squadrons (the 97th and 66th) and all units of the Civil Air Patrol then engaged in antisubmarine patrol in the Gulf Sea Frontier. Its headquarters, temporarily located at Charleston, South Carolina, was ultimately established at Miami, Florida. The command relationship between the Gulf Task Force and the Gulf Sea Frontier was similar to that which existed between the I Bomber Command and the Eastern Sea Frontier.28

It soon became evident that the need for Army air patrol in the Gulf area exceeded the ability of this small task force to meet it. Accordingly, a few days after it had been established, General Arnold requested the Third Air Force to use certain of its training units for antisubmarine patrol in the course of their regular over-water training missions, such flights to be directed by the Gulf Task Force. For its part, Third Air Force, various units of which had maintained sporadic patrols of the Florida and Gulf areas since December 1941, proposed to place eight B-17’s, operating from Barksdale Field, Louisiana, and

MacDill Field, Florida, at the disposal of the Gulf Task Force. A plan embodying these recommendations was put into effect on 1 July 1942. In addition, two observation groups (the 128th and the 124th) were attached to the Gulf Task Force in early July primarily for the purpose of forming and training Civil Air Patrol groups in the Gulf area. Meanwhile, arrangements had been made to establish a joint operations center at Miami, to be built on the general pattern being evolved for similar purposes in New York City. The project was initiated in June. By September, the I Bomber Command was operating from ten bases scattered along the coast line from Westover Field, Massachusetts, to Galveston, Texas.29

During April, May, and June of 1942, I Bomber Command planes, and those serving under the operational direction of that command, attacked enemy submarines at a steadily increasing rate. Although hours flown during this period showed a slight decrease in monthly total from the record activity registered in March, the number of attacks for the three-month period turned out to be almost seven times greater than for the first three months of the year. And of the fifty-four attacks recorded, at least seven appear to have resulted in some damage to the enemy craft. As yet, however, no attack had resulted in the destruction of a U-boat. Nonetheless, the total harassing effect seems to have been considerable, as is suggested by the enemy’s tendency to shift the attack to the areas less effectively covered by air patrol.30

More promising was the tactical experience gained in the course of those first six months of continuous operations. It was necessarily a period of training and experimentation, and the later effectiveness of the Army antisubmarine campaign depended to a large extent on the experience gained from January to July of 1942. Fortunately, both Army and Navy antisubmarine forces were able to draw largely on the experience of the British for their initial stock of tactical data, and they made extensive use of their opportunity. Of particular aid to the AAF units was the help given by two liaison officers sent to the United States in February.31

Study of British intelligence data indicated that, prior to August 1941, British aircraft had executed 270 attacks on U-boats, as a result of which two U-boats had been definitely sunk and five more probably sunk. On the basis of this experience, not wholly encouraging in the sum total, British analysts had been able to arrive at certain very

important tactical conclusions. For example, they determined that the probability of a successful attack on a long-submerged submarine was extremely small. Conversely, only U-boats which could be attacked while on the surface or within, at most, thirty seconds after submerging offered profitable targets, a fact which encouraged the use of depth bombs set for detonation at relatively shallow depths, say twenty-five to thirty feet. British experience also indicated that, to insure a successful attack, one of the bombs dropped must explode within little more than a dozen feet of the U-boat’s hull.32

Such items of tactical information the American units welcomed and found very valuable. But much of the job of hunting U-boats had necessarily to be learned by doing. Consequently, during these early months of the campaign, each AAF unit operated for tactical purposes in large part as its commander saw fit; and the data on each attack were eagerly studied in I Bomber Command headquarters with a view to the evolution of a tactical doctrine of its own. Many of the lessons were elementary. It was found to be well, for instance, not to pay too much attention to the appearance of oil slicks on the surface of the water, as they did not indicate necessarily the presence of a submarine. From the air, too, it was easy to mistake the wake left by the fin of a shark for that produced by the periscope of a submarine, a fact from which the larger forms of marine life may on more than one occasion have suffered.33

Many other lessons involved increasingly subtle understanding of the conditions under which attacks might be undertaken with the greatest chance of success – the use, for example, of cloud cover as a means of concealment and surprise in daytime attacks, and an approach toward the target down the moon path by night. If a submarine submerged before an attack could be delivered, it was found to be advisable for the attacking plane to use “baiting” tactics, which involved leaving the area for a good interval and then returning to it in the hope that the enemy might in the meantime have surfaced and be thus open to another attack. In many other respects the learning process was far from complete by July of 1942. Opinion still differed as to the advisability of dropping an entire bomb load on the initial contact; and it was still debated whether it was better to attack the U-boat from the side or along its longitudinal axis. But the data was beginning to arrive in quantity sufficient soon to remove such questions from the realm of opinion. Finally, the development of

radar had opened up an entirely new field for investigation in antisubmarine tactics, though as yet little had been done in this country along that line and only a few Army aircraft were specially equipped.34

Generally speaking, Army antisubmarine operations fell into three broad categories: routine patrol of areas in which the threat of enemy action existed, special patrol of an area in which a particular U-boat was known to be lurking (a process known sometimes as a “killer hunt” and carried out often in conjunction with naval air and surface forces), and cover for convoys sailing within range of land-based aircraft. The first two of these activities, involving as they did an attempt to search out and attack the enemy, constituted the offensive phase of the campaign. The last, consisting of the direct protection of shipping, was primarily defensive in character, although it was recognized that the vicinity of a convoy was a likely place for U-boats to be found.35 It was not, however, until after 15 May 1942 that the Army units were called upon for regular convoy cover, for it was not until that date that the Navy felt able, in terms of escort vessels and aircraft, to inaugurate a convoy system for coastal shipping.36 Beginning in May, I Bomber Command aircraft were requested by the sea frontier commanders to take part in the protection of convoys from Key West to the Chesapeake Bay, and during the summer steps were taken to extend protection to the oil and bauxite shipping in the Caribbean. The Navy was able to assume a large share of this convoy air cover. By the end of May, it was employing long-range PBY type aircraft with an endurance of fifteen hours over the most distant convoy routes.37 Nevertheless, convoy protection was already competing strongly for the services of AAF antisubmarine units.

Six months of experience in U-boat hunting began to bear fruit during July, August, and September in a noticeably higher level of success in the attacks made by units operating under I Bomber Command control. Although the number of attacks fell off rapidly after the high record of June, the proportion of those considered damaging to the submarine increased remarkably. Whereas during the previous three months only seven of the fifty-four attacks were thus assessed, during July, August, and September eight out of twenty-four attacks were believed to have damaged the enemy craft, and one, executed on 7 July, resulted in a sure “kill.”38

Still more interesting is the fact that the frequency of attacks made

by Army aircraft shows a rough correlation with the density of U-boats in the coastal waters and with the rate of merchant vessel sinkings. Since May the Germans had shifted the weight of their effort steadily southward until, by September 1942, they had virtually abandoned the Eastern and Gulf Sea frontiers. After 4 September, no sinkings occurred in those waters as a result of enemy submarine action during the remainder of the year. June 1942 had witnessed the pattern of sinkings moving toward the Gulf and Caribbean areas. By August, the Gulf was practically free of sinkings, which by that time were heavily concentrated around Cuba and in the waters off Trinidad. By September, the enemy had given up attacks around Cuba, Haiti, and Puerto Rico but continued in the Trinidad area, where since February of 1942 a group of submarines had been consistently successful in the vulnerable oil and bauxite shipping lanes.39

This gradual withdrawal of the enemy reflects the steady increase in both the weight and quality of the American antisubmarine effort. That effort involved the operation of Navy and Army units, of surface and air craft, and it would be futile to try to evaluate precisely the relative importance of any one factor. The coastwise convoy system, which the Navy was able to inaugurate in May, made it possible for shipping to move in the American waters with greater security, and it thereby did much to reduce the margin of profit the U-boat command might expect from its activity in the western Atlantic. But it is also true that this margin of profit was cut drastically by the extension and increasing effectiveness of air patrol. In the eastern Atlantic, the U-boat captains had demonstrated their unwillingness to operate in areas systematically covered by aircraft, and it appears that they continued to follow this policy in the western Atlantic as well. Their decision, to be sure, did not result directly from the damage sustained from attacks by American aircraft. In the course of 59,248 operational hours flown between January and October 1942, the I Bomber Command reported not many more than 200 sightings, in only eighty-one of which instances did attacks of any sort ensue. These attacks resulted in the destruction of one U-boat, the probably serious damage of six, and the less serious damage of seven more. Attacks by naval aircraft occurred with increasing frequency, amounting in all to well over half the total made by aircraft during the period and in the area under review. But it is still doubtful whether the total weight of air attack proved decisively

damaging to the U-boat fleet.40 Rather, aircraft made their contribution by forcing the enemy to submerge so frequently and to stay down for such long intervals that their targets disappeared and their activity became handicapped to the point where the returns barely justified the expense.

According to postwar statements by Admiral Doenitz, the balance sheet of profit and loss for activity in the western Atlantic favored the submarine for a longer period than the U-boat command had anticipated. The success of the first U-boats in American waters had been, as expected, very considerable. American defenders were inexperienced, whereas U-boat commanders had behind them more than two years of operations. Every available submarine had, therefore, been sent into the American zone. But it had been expected that the resulting successes would soon fall off, and-it was a matter of some surprise to the Germans that until the end of September 1942 their efforts remained profitable despite the long inoperative passage out and back and despite the fact that the rapidly stiffening defenses off the northeast coast had long since forced the U-boats to look farther south for easy and economical victories.41

Although driven from the home waters, and to a possibly decisive extent by air power (Admiral Doenitz tells us that air reconnaissance and attack was the antisubmarine measure most feared by the U-boat command), the enemy had by no means been defeated. He had merely concentrated his efforts in other areas – and so effectively that in November 1942, two months after he had virtually abandoned the American home waters, he destroyed more Allied and neutral shipping than in any month since June.42

While I Bomber Command was helping to drive the U-boats from the home waters, and in the process was becoming an organization especially trained and equipped for antisubmarine warfare, other AAF units were also actively engaged against enemy submarines in other parts of the western Atlantic. A few Army B-17’s, seldom more than a squadron, continued during 1942 to supplement the Navy’s air arm in the Newfoundland area.43 But it was in the Caribbean that the Army units saw their most intensive and continuous action. Units of the Caribbean Air Force, organized on 1 March 1942 into the Antilles Air Task Force in compliance with an order from the parent organization dated 16 February, devoted almost their entire effort for the remainder of the year to antisubmarine operations

in support of the naval forces of the Caribbean Sea Frontier, from which headquarters they received their operational direction.44

The U-boats had made their presence felt in the Caribbean on 16 February. Attacking with impunity, they sank several tankers off Aruba on that date and even shelled an oil refinery on the island itself.45 By the end of September 1942, they had sunk 173 merchant vessels in the western area of the Caribbean Sea Frontier. Shipping losses reached their peak in August, with a total of thirty-three sinkings in that area.46 The Caribbean, which offered an especially valuable opportunity in the oil and bauxite traffic between the Curacao-Aruba-Trinidad area and the continental United States, had thus become a favorite hunting ground for the enemy raiders.

The forces available to the commander of the Caribbean Sea Frontier, including those of the Antilles Air Task Force, were admittedly insufficient during the early months of 1942 to provide effective defense. Army bombardment forces available in February 1942 included not more than forty operational B-18’s in the medium bomber class, plus about seven light bombers of the A-20 type. They included no long-range planes at all. These meager bombardment forces, together with a few pursuit squadrons, were scattered about the Caribbean in Trinidad, Curacao, Aruba, St. Lucia, Surinam, British Guiana, Puerto Rico, St. Croix, and Antigua. By the end of the summer, the task force could count on few if any more bombers than it had reported in February, although its strength in fighters had more than doubled.47 The U.S. Navy meantime, however, had materially increased the scope and effectiveness of its effort in the Caribbean, and although the Antilles Air Task Force had remained in strength substantially as before, its units had acquired valuable experience since February. Whereas prior to July they had executed very few attacks, in July and August they reported more than a score.48 During the fall of 1942, the U-boat command sharply reduced its activity in the Caribbean to concentrate its attention on the North Atlantic convoy area and the approaches to Northwest Africa.

Despite its almost exclusive preoccupation theretofore with submarine warfare, the Antilles Air Task Force remained at the end of 1942 officially a striking force whose primary function was to guard against possible attack on the Panama Canal. The prolonged presence

A B-18 on Patrol in the Caribbean

of a French aircraft carrier at Martinique continued to lend an air of immediacy to the threat which originally had determined this mission, and it was doubtless for this reason that the Antilles Air Task Force never evolved, as did I Bomber Command, into an organization shaped for the primary purpose of antisubmarine warfare. Indeed, by the fall of 1942 plans were under way for extending the activity of I Bomber Command, in its as yet unofficial capacity as the AAF antisubmarine force, to bases in the Caribbean; and in August, a few B-18’s of its 40th Bombardment Squadron had been in fact sent on detached service to the Puerto Rican and Trinidad areas. This experiment in sending antisubmarine forces to outlying bases on a detached service status proved administratively unsatisfactory, but plans nevertheless continued to point toward I Bomber Command as the organization that would be responsible for AAF specialized antisubmarine activity wherever it might be undertaken.49

When on 15 October 1942 the I Bomber Command became the Army Air Forces Antisubmarine Command with a materially expanded mission, it was still a comparatively small organization and one as yet inadequately trained and equipped for its task. From a high point of 216 planes in July, a point reached just after the submarine menace within the area of its operations had begun to decline, the I Bomber Command had suffered a decrease in combat strength until in October it reported only 148 aircraft. Of these, twelve were B-17’s, fourteen B-18’s, thirty-five B-25’s, and three B-24’s; the rest, a mixture of A-20’s, A-29’s, and B-34’s, lacked sufficient range for anything except strictly coastal patrol. Some twenty-seven planes were at this time equipped with radar; this number, too, represented a marked decline since July. But the command had made great progress toward becoming an effective antisubmarine striking force. It had accumulated the many benefits of a wide and varied experience, and its personnel stood ready to provide effective leadership in the definition of tactical doctrine, the shaping of training, and the adaptation of equipment to the peculiar requirements of a larger mission. It had come to be recognized that the long-range B-24 was especially well suited to the demands of antisubmarine warfare, and in September the command had received the first of the planes that would thereafter become the principal reliance in the AAF’s antisubmarine effort.50

Genesis of the Army Air Forces Antisubmarine Command

Meanwhile, the American high command was struggling with the more fundamental problems of antisubmarine policy. As has already been noted in this volume and will be noticed repeatedly hereafter, the question of shipping proved again and again the most crucial of those faced in attempts to meet the demands of our hard pressed forces in the Pacific and to provide for an early assumption of the offensive against Germany. And so threatening to the basic strategy agreed upon for the conduct of the war was the submarine attack that no possibility of taking effective action against it could be overlooked.

Two things the submarine crisis had immediately made clear: an effective antisubmarine campaign would require more aircraft than could be supplied from current production designed for Navy use, especially in view of the many demands on naval air strength; and a large proportion of the necessary aircraft would have to consist of land-based types, admittedly better suited, because of their speed, range, and firepower, for antisubmarine attack than the seaplane.* It was soon evident, too, that these requirements could be met either by turning over to the Navy a force of Army land-based bombers sufficient to allow that service to accomplish the task by itself, or by setting up a separate command within the AAF to be specially trained and equipped for antisubmarine warfare and with that as its sole duty. Thus the AAF units engaged in the anti-U-boat war became almost at once the subject of a jurisdictional controversy.

The issue first arose in acute form when the Navy acted early in 1942 to secure a force of land-based bombers for its own use. On 15 January, the Air Staff had under consideration a request from Rear Adm. John H. Towers, chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, for the transfer to the Navy from future production of Army-type

* On 5 March 1942, Admiral King wrote to General Arnold as follows: “The experience of the last two winters has demonstrated that naval aviation missions such as convoy escort, observation, scouting and patrolling over the sea, and the protection of shipping in the coastal zones, cannot be accomplished by seaplanes based on ice-bound bases in the North Atlantic and Pacific areas. In addition to this experience, a study of the purely naval operations of the Coastal Command of the Royal Air Force has led to the conviction that for such missions, carried out from prepared fixed bases, multi-engined landplanes have certain characteristic advantages m increased range, ease of maintenance, and facility of operation, over seaplanes.” The Navy’s carrier-based planes which lent important weight to the antisubmarine war in its later phase were not employed in the Atlantic until March 1943

planes of approximately 200 B-24’s and 900 B-25’s and B-26’s.51

A formal request by Admiral King to the Chief of the Army Air Forces on 14 February sought provision for the transfer of a total of 400 B-24’s and 900 B-25’s, and expressed the hope that by allocation from current production it might be possible to meet requirements for 200 B-24’s and 400 B-25’s prior to 1 July 1943.52 It was argued by Admiral Towers in support of the Navy’s claim that arbitrary limitations as to type of aircraft or weapon employed should not be allowed to restrict the effectiveness of either AAF or naval aviation. He further argued, citing the Army’s need for dive bombers which was currently being met in part by a Navy-developed type, the mutual advantage of an exchange of equipment.53 To General Arnold’s headquarters, however, the problem assumed a quite different aspect. Preoccupied with the difficult task of meeting urgent defensive requirements in all theaters and at the same time of building up a bombardment force with which to carry the air war into the heart of Germany, that headquarters viewed the proposed diversion of 1,300 bombers with dismay. Estimated total deliveries of the B-24 type to June 1942 amounted only to 230 aircraft. Estimated deliveries of all heavy bombers for the calendar year 1942 were no more than would be required for the equipment of thirty-four heavy groups set up without provision for depot reserve. As for the medium bombers, it was anticipated that without further diversion the Army Air Forces would suffer a shortage of 850 airplanes.54 The AAF’s first reaction was, therefore, expressed in the following unequivocal terms: “There are no heavy or medium bombers available for diversion to the Navy.”55

At the same time, Arnold and his staff faced a serious dilemma. On the one hand, they felt committed to the task of mounting the strategic bombardment offensive against Germany, a task which already had been made tentatively a vital part of the combined Anglo-American strategy and in which the Air Staff had great faith. On the other hand, the German submarine attack, if not in some measure countered, could quite conceivably prevent the build-up in the United Kingdom for the bomber offensive – indeed, it could, and was, endangering the entire Anglo-American war effort. There was consequently no question but that Army bombers would have to be employed in antisubmarine operations. If they could not be provided in the numbers requested by the Navy for antisubmarine and other

activities, they would have to be provided for the purpose of countering the U-boat threat in whatever quantity considered feasible in the light of other commitments.

Such being the case, the Air Staff preferred to retain possession of the antisubmarine bomber forces to be made available and to employ them in accordance with the Army responsibility set forth in joint Action for operations “in support of or in lieu of naval forces.” In that way, it was felt, a serious duplication of equipment, maintenance, and supply would be avoided, which otherwise would eventually “deny the essential difference between armies and navies.”56 The question of duplication was all the more serious because it was evident that the bombers requested were not to be employed exclusively for antisubmarine operations in the Atlantic.57 In other words, the implications of the proposed transfer were far reaching in their effect on the fundamental question of control of land-based aviation engaged in seaward operations.58

General Arnold proposed, therefore, as a solution of the problem of providing additional forces for antisubmarine warfare a compromise which would retain the principle of ultimate responsibility as set forth in joint Action and which enjoyed the support of precedent. In a letter of 9 March 1942 to Admiral King, he proposed “the establishment of a Coastal Command, within the Army Air Corps, which will have for its purpose operations similar to the Coastal Command, Royal Air Force,” operating “when necessary” under the control of proper naval authorities. The advantages of such an organization, he felt, would be compelling. It would be uniquely trained and equipped for the job. It would also possess the flexibility necessary for antisubmarine action, and could readily be reduced in strength as the need decreased, the units then simply reverting to normal bombardment duty without becoming stranded wastefully in a naval program which presumably would then have no place for them.59 This proposal of General Arnold’s sounded the keynote for AAF policy in the negotiations which culminated in the creation of the AAF Antisubmarine Command.

It also reflected the profound influence exerted by the RAF Coastal Command on AAF thinking. That the Coastal Command should provide something of a blueprint for a similar organization in the United States was very natural, for it had pioneered in antisubmarine warfare under circumstances roughly analogous to those

in which the American forces found themselves fighting in 1942. The British had solved the problem of coordinating the activities of land-based aviation with those of the Royal Navy and the Fleet Air Arm by creating a special RAF command, equipped and trained for sea search and attack and placed for purposes of operational control under the Admiralty. Details of this arrangement had been made available to interested headquarters in Washington by the British officers detailed to advise the American antisubmarine forces. Admittedly far from perfect, the system they described bore the authority of more than two years’ experience in joint action, experience marked by close and effective cooperation between the services. The Admiralty set forth the general pattern of antisubmarine operations and left it to Coastal Command to direct the activities of its own units within that over-all strategic pattern. Sea and air officers in charge of operations worked in the same quarters from identical intelligence data presented on the same plotting charts. Interchange of information thus became virtually automatic.* 60

No immediate results followed General Arnold’s proposal. By May, however, the submarine situation itself pointed more imperatively than words to the need for some change in the existing system of control. Most of the May sinkings had occurred in the Gulf and Caribbean areas. Scarcely adequate to protect shipping in the Eastern Sea Frontier, the existing organization of antisubmarine operations proved powerless to cope with a greatly extended area of activity. Above all, there was the ugly fact that during that month sinkings in both these sea frontiers had risen to an alarming figure. Despite energetic efforts on the part of both Navy and AAF agencies to meet a rapidly changing situation with machinery constructed essentially on static principles, the extension of AAF antisubmarine operations merely emphasized the faults inherent in the existing system of command and control.

The agreement reached late in March had placed unity of command over all air forces operating over the sea in the coastal defense areas in the hands of the sea frontier commanders. This seemed a convenient enough arrangement for the time being, but in reality it merely made more definite what had hitherto been left vague. It did

* The contrast between this concept of operational control and that followed by the U.S. Navy should be noted. The U.S. Navy preferred to exercise more detailed supervision of the operations of Army units assigned to its control through such lower echelons of command as the sea frontier and the naval district.

nothing to meet the problem of deploying land-based aviation effectively in antisubmarine warfare. The trouble was that no single command, either in the Navy or Army, was solely responsible for the conduct of the antisubmarine war. The result was that a multiplicity of regional headquarters within a system constructed originally to meet the needs of a static defense robbed the air arm of what the AAF considered its primary advantage, namely its mobility as an offensive striking force.

Most AAF units engaged in the campaign served under the operational control of the I Bomber Command, which remained the only organization capable of coordinating such an enterprise. But the I Bomber Command was still theoretically a bombardment force, and as long as it retained a dual responsibility its training and tactical development had literally to be carried on at two levels – for high-level bombardment and for low-level attack against submarines. This situation prevented it from concentrating as fully on the anti-U-boat war as the nature of that conflict required. The system over which it presided was, moreover, loosely integrated. The Civil Air Patrol served under the I Air Support Command for operational control. I Air Support Command, in turn, operated under the control of I Bomber Command. Units of the Third Air Force, brought in as an emergency measure to meet the crisis in the Gulf area in May, operated under the control of the Gulf Task Force of the I Bomber Command. And this system, such as it was, as yet did not extend to the Caribbean, where the Antilles Air Task Force operated independently under the Caribbean Sea Frontier. Administratively speaking, the situation was even more complicated because all units were administered through either the First Air Force or the Third Air Force, both of which had to go through their respective defense command headquarters before reaching Headquarters, AAF.61 Within the Army itself, then, the organization was poorly adapted to meet the challenge of an opponent that operated with extreme mobility under a strictly unified command.

Another serious difficulty arose from the fact that the AAF units were, according to joint agreement, allocated to the sea frontier commanders. These allocations were treated by the Navy as more or less permanent arrangements which, except in grave emergency, would prevent the AAF units serving under one frontier commander from operating in the territory of another. This tendency to tie

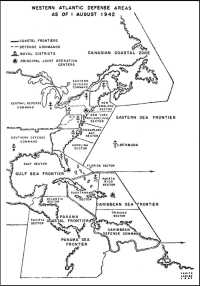

Western Atlantic Defense Areas as of 1 August 1942

down the antisubmarine aviation to regional commands fortunately did not extend to the naval districts, for if the practice had been followed there it would have vitiated the effectiveness of the air arm. Mobility, on which this effectiveness was considered to depend, was nevertheless seriously obstructed by the difficulty of moving aircraft assigned to one sea frontier to meet sudden requirements in an area under the jurisdiction of another.62 Although a function of COMINCH, the antisubmarine campaign in the western Atlantic remained in practice a decentralized effort, its flexibility, especially in the deployment of land-based aircraft, and its integration of tactical procedure seriously compromised by a rigid system of regional control.63

A centralized command thus became the key to AAF thinking as far as it concerned the participation of Army air units in the antisubmarine war. That campaign needed other things, to be sure. It needed better equipment, a better training program, a better communications system. Above all, AAF observers felt it needed a truly mobile air arm. But all of these requirements depended in one way or another on the attainment of a more unified command. Opinion, however, in AAF quarters was not quite unanimous as to the nature and extent of this unified jurisdiction. Obviously the entire American antisubmarine campaign, involving surface as well as air forces, would profit by centralized control if any part thereof would. And, if operational control by the Navy were to continue, as seemed likely, then it would be well for a single Navy commander, rather than several, to exercise that control over AAF units. But many AAF observers, apprehensive of the direction in which a unified naval command would lead the air forces allocated to it, preferred to think in terms of a unified command for antisubmarine aviation as a matter of primary importance, assuming, no doubt, that such an air command would be capable of answering the needs of the air arm even under the over-all control of the Navy. Some felt that this command should consist only of land-based units; others argued that it should also include Navy and Marine heavier-than-air craft engaged in the antisubmarine campaign. All agreed, however, that the successful participation of the AAF in the Battle of the Atlantic depended on the creation of a separate command, comprising at least the AAF units, responsible directly to Headquarters, AAF, and trained and equipped for the sole purpose of hunting U-boats.64

What gave particular point to these arguments was the radical divergence in strategic policy existing between the AAF and the Navy with regard to the employment of land-based antisubmarine aviation. That difference in concept helps explain both why the AAF was concerned to create an antisubmarine coastal command of its own, and why it hoped to secure an interpretation of the Navy’s operational control in terms comparable to those governing RAF Coastal Command. Almost from the beginning, the question had arisen whether aircraft of the AAF should be employed defensively, that is, primarily for the protection of convoys, or as a mobile striking force capable of carrying the battle to the enemy wherever he might be hunting.

Naval doctrine emphasized the basically defensive functions of convoy escort and the patrol of more or less fixed sectors of the coastal waters. In June, Admiral King expressed the official Navy position on this point with the utmost clarity in a letter to General Marshall dated the 21st: “I might say in this connection that escort is not just one way of handling the submarine menace; it is the only way that gives any promise of success . ... We must get every ship that sails the seas under constant close protection.”65 AAF students of the problem expressed an equally marked preference for the offensive. Defensive measures, they maintained, while essential to the immediate task of protecting shipping and for that reason deserving a high priority, could never dispose of the U-boat menace but must be supplemented by a vigorous offensive campaign in which the strategic movement of the submarine fleet could be promptly countered by a corresponding shift in the weight of air attack. Admittedly, the airplane as it was equipped in the summer of 1942 lacked the killing power necessary to destroy many submarines. But it was improving; and in the meantime, it possessed great searching power by means of which it could render an area unprofitable for the enemy to work.

Whenever a sinking occurred or the presence of a submarine was detected, long-range planes should be sent to the spot for intensive search, a policy which required a highly mobile force.66 Here again RAF Coastal Command lent the support of its experience. Air Marshal P. B. Joubert, when asked in August 1942 for a statement of the principles upon which his command operated and to which it owed its success, replied in part that “while a certain amount of close escort of convoys, particularly when threatened, is a necessary feature

of air operations, the main method of defeating the U-boat is to seek and strike.” He continued, “The greater portion of the air available should always be engaged in the direct attack of U-boats and the smallest possible number in direct protection of shipping,” for it had been the experience of the RAF “that a purely defensive policy only leads to heavy loss in merchant shipping.”67

With the need for reform in the antisubmarine campaign in mind, and impelled by the desperate shipping situation, the War Department in May 1942 demanded action. On the 20th of that month, the Assistant Chief of Staff, Operations Division, directed the commanding generals of the AAF and the Eastern Defense Command to take necessary steps to improve the antisubmarine activity being undertaken under the First Air Force and the I Bomber Command. In addition to indicating certain physical reforms, he requested General Arnold to reorganize the I Bomber Command in such a way as to “fulfill the special requirements of antisubmarine and allied air operations, in consonance with the Army responsibility in operating in support of, or in lieu of naval forces for protection of shipping.”68 By taking this action, the War Department recognized that the participation of its air arm in the war against the U-boat was no longer merely an emergency measure, but one likely to continue as long as the submarine menace lasted. And in doing so it found itself in a strong position. The AAF possessed vitally needed weapons and had already taken part in antisubmarine operations for nearly five months, during which time it had laid the ground work for an effective organization, had developed special techniques, and had prepared plans for a more ambitious effort.

The directive of 20 May stated further that, although unity of command was vested in the Navy, the Army must be prepared to submit recommendations and to take every action to make antisubmarine warfare fully effective. Accordingly, plans of a more or less specific nature soon appeared, plans embodying both the jurisdictional and the strategic policy of the AAF, sometimes in their more extreme forms.69 Official action, however, took a much slower course, dictated by the immediate, practical need for a compromise settlement which would recognize the primary interests of both services.

In a memorandum to Admiral King, General McNarney, Deputy Chief of Staff, on 26 May outlined the War Department plan for reorganizing its antisubmarine program. The I Bomber Command

was to be organized as a unit for antisubmarine “and related operations” on the East and Gulf coasts. Air bases were to be established at strategic locations in order to take maximum advantage of the mobility of land-based aircraft. As soon as available, ASV-equipped aircraft would be welded into units “particularly suited for hunting down and destroying enemy submarines by methods developed by our experimental units which have been operating off Cape Hatteras.” Mobility was to be the keynote of this reorganized force. When a unit moved to an area outside the Eastern Defense Command, it would operate under the control of the particular sea frontier commander concerned, but it would still remain assigned to the I Bomber Command. Movement to and operation in areas beyond the jurisdiction of the parent organization would be viewed as a temporary detachment.70

Admiral King’s reaction to these cautious proposals was expressed with equal caution. While approving in general of the plan, he made it clear that he intended to make no radical change in the existing system of operational control vested in the sea frontier commanders. It would be necessary for the commander of the Eastern Sea Frontier, who was responsible for the protection of shipping in both the Eastern and Gulf Sea frontiers, to request air coverage for convoys operating outside the Eastern Sea Frontier from the commander of the Gulf Sea Frontier. This arrangement, he explained, did not present any administrative difficulty. It would mean only that aircraft attached to one sea frontier would not be required to operate in another sea frontier “unless exceptional conditions make it necessary.” In a note to the sea frontier commanders concerning General McNarney’s proposal, he further clarified his policy by stating that the division of aircraft, both Army and Navy, as between the sea frontiers, would be a matter under the cognizance of his headquarters.71

While these discussions continued with little promise of radical reorganization in the program as a whole, shipping losses continued to occur at an appalling rate. On 19 June, General Marshall expressed his fear that “another month or two” of similar losses would “so cripple our means of transport that we will be unable to bring sufficient men and planes against the enemy in critical theaters to exercise a determining influence on the war.”72 This note of alarm elicited from Admiral King an energetic defense of the system of convoy and an equally positive criticism of the AAF doctrine of an air offensive

against the U-boat at sea. Patrol and hunting operations had time and again proved futile, he asserted. The “killer” system, whereby contact with a submarine is followed continuously and relentlessly, required more vessels and planes than were available. The only way he believed it possible to eliminate the U-boat menace was to wipe out the German building yards and bases-”a matter which I have been pressing with the British, so far with only moderate success.”* But even this form of offensive strategy would do little more toward making the Atlantic safe for Allied shipping than a complete system of convoy cover and escort could achieve.73

He therefore proposed extending and intensifying the convoy system as the most effective step toward reducing the submarine menace. Specifically, he urged the Army to make available as air cover for escorted convoys a total of 500 planes, 200 of which should be deployed in the Caribbean and Panama Sea frontiers, where the convoy system was being extended in order to protect the vital oil and bauxite shipping from South America. These 500 planes, he felt, were a bare minimum, but they would effectively supplement the total of 550 patrol and 300 observation planes the Navy hoped to employ in the four western Atlantic sea frontiers.74

On 7 July 1942, in a memorandum to the Secretary of the Navy, the Secretary of War reopened the question of antisubmarine organization with a fresh proposal. He called attention to the increasing rate of shipping losses and to the current antisubmarine effort which, he said, had proved “largely ineffective.” The trouble, he continued, lay primarily in an inefficient system of command and control with regard to ASV-equipped aircraft:–

Authority and responsibility is at present divided between many commands and echelons of command. The flow of communications through so many channels inevitably consumes time and effort and interferes with the most effective employment of the forces available. Centralized control to enable the instant concentration of available forces at points of major threat is required. This situation has assumed such a critical aspect that drastic measures should be taken immediately.75

In order, therefore, to provide a greater degree of flexibility “than appears to exist under the Naval District system and our Eastern Defense Command set-up,” and to take advantage of the mobility of

* It may be noted in this connection that from October 1942 until June 1943 the Eighth Air Force had as its objective of highest priority the bombing of German submarine shore facilities.

aircraft, he suggested that a single sea frontier command be established, extending from Maine to Mexico and covering the Atlantic and Gulf areas, with a naval officer in charge of it. The specialized antisubmarine command then being developed by the Army Air Forces would be placed under the operational control of that naval officer. To this proposal, Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox replied in much the same words as used by Admiral King a month earlier: the answer to the antisubmarine problem lay “in augmenting our forces rather than in further changes in the system of command which now seems to be working effectively.”76 In reply, Secretary Stimson stated that the War Department was planning to provide for antisubmarine operations all reinforcements “that can be diverted from other tasks.” Specifically, 175 ASV-equipped bombers were to be furnished I Bomber Command, and it was felt that this force would be adequate if freed from restrictions “which are inherent in inflexible command systems based upon area responsibility.”* 77