Chapter 14: Commitments to China

It will be recalled that just at the close of Allied resistance in the Netherlands East Indies, General Brereton, under instructions from General Brett which were subsequently confirmed by the War Department, flew to India for the purpose of organizing an American air force in the India-Burma area. He had been preceded by Col. Francis M. Brady and was accompanied by a handful of AAF personnel who would form a nucleus for the new air force. Six heavy bombers were flown up from Java, and orders were issued for all planes and crews en route to the Netherlands East Indies by the African ferry to stop in India. Three vessels which had left Fremantle in Australia on 22 February, in company with the ill-fated Langley and Sea Witch, were on their way across the Indian Ocean with the ground echelon of two squadrons of the 7th Bombardment Group (H), the 51st Air Base Group, personnel of the 51st Pursuit Group, and ten P-40’s.* At Patterson Field, Ohio, the Tenth Air Force had been activated on 12 February. It was assigned to the newly created China–Burma–India theater,1 and General Brereton formally assumed command on 5 March. Such were the meager beginnings of an organization forced to operate at the end of a longer supply line than that of any other existing American air force, over distances within its theater that exceeded considerably those embraced by the bounds of the United States, and in an area possessed of few of the industrial facilities upon which air power is directly dependent.

It was the third extraordinarily difficult assignment which had fallen to the lot of General Brereton in the initial stages of the war with Japan. Formerly commander of the Far East Air Force in the Philippines

* See above, pp. 396–97.

and more recently of American air units operating in the Netherlands East Indies, he was now to command an air force based in India with a mission for the support of China. Key decisions would involve consideration of the interests, not always identical, of two major allies. Once again he had to improvise an organization in the face of a rapidly advancing enemy whose conquest of Burma, which held the key to any plan for the immediate assistance of China, would be completed before the Tenth could be given the means to fight. Lacking personnel, planes, and other equipment that make up an air force, Brereton would not even command the major American air unit operating within the theater. For ere the famed American Volunteer Group (AVG) had been inducted into the AAF in July, General Brereton was transferred, with such striking force as the Tenth possessed, to the Middle

The AVG

The exigency of war had determined the time and circumstances of General Brereton’s arrival in India, but the decision to conduct aerial operations in support of China came as a logical culmination of a well-defined American policy extending back to the Japanese occupation of Manchuria in 1931. At that time the American people had been unprepared to go beyond a general endorsement of the policy of nonrecognition for such conquests enunciated by Henry L. Stimson, Secretary of State, who was now serving as the Secretary of War. But we had watched with growing concern the progress of Japanese forces in China, and with increasing admiration the evident purpose of the Chinese to continue their resistance. This concern had become acute by 1941, when all approaches to China had been sealed off except for the Burma Road, a tortuous truck route hewed through the mountains between Lashio and Kunming in 1937–38.2 A quickened interest displayed in the Sino-Japanese conflict by the American government in 1941 reflected not merely a growing popular demand, in which the traditionally isolationist section of the press tended to join, but the government’s own concern over the prospect of an early involvement in war with both Germany and Japan. If we were to fight both of them (and the two had entered recently into a formal alliance clearly directed against the United States), the most realistic of considerations argued for every possible effort to strengthen China, especially in view of strategic plans then taking

shape which called for a holding effort against Japan until the major foe in Europe had been defeated. In anticipation of the passage of the Lend-Lease Act of 11 March, Mr. Lauchlin Currie had gone to China as economic adviser to President Roosevelt for study of her needs.3 He was followed in the spring by Brig. Gen. Henry B. Clagett, who was sent from the Philippines as an Air Corps officer for the purpose of reporting both on Chinese requirements and on the potentialities of the area for air operations.4 China’s requests for assistance under lend-lease aid emphasized the need of trucks to be employed on the Burma Road and of aircraft for the defense of her cities.5 Trucks and technical assistance in the operation of the Burma Road were readily provided, but there was a critical shortage of aircraft.6 At a time when our own expanding air arms easily could have absorbed the entire output of the American aircraft industry, there was a large backlog of British orders; and the problem was complicated further by the desire to send aid to Russia after the German attack in June. Nevertheless, August brought firm commitments to China for the provision of more than 300 training and combat aircraft, chiefly of models considered obsolescent for AAF and RAF needs, and cadres of American pilots and ground crews to render advisory assistance in the maintenance and employment of the planes. It had been agreed, moreover, that 500 Chinese fighter pilots, 25 bomber crews, and 25 armament and radio mechanics would be trained by the Americans, the first contingent to begin its training on 1 October.7 In that month an American military mission under Brig. Gen. John Magruder reached China to accomplish an over-all study of problems of supply and to provide necessary instruction in the use of American made equipment.8 Thus, by the fall of 1941 the way had been prepared for a strengthening of China’s resistance to Japanese aggression through the provision of matériel, training, and technical guidance.

Substantial quantities of material had been delivered or were under movement by that time, but certain features of the program, and notably those pertaining to a strengthening of the Chinese Air Force, required time for their development. And of time, by now, there was precious little; for the Burma Road, so crowded as to be subject to utter confusion, had been brought within the range of Japanese bombers. The prostrate Chinese Air Force for some time yet would be unequal to defense of the road, and to assign units of the American air force for the purpose was out of the question. But an answer to

the problem had been suggested by a retired Air Corps officer, Claire L. Chennault, who since 1937 had been serving as special adviser to the Chinese Air Force.

Known to Americans chiefly as a member of the “flying trapeze” team which over preceding years had electrified spectators at air shows and races by its demonstration of formation flying, Chennault was also a diligent student of fighter tactics.9 Having been retired from the Army in 1937 because of defective hearing, he promptly accepted the opportunity offered to him by the Chinese government to put some of his theories into practice under combat conditions. In China, he found the procurement of necessary equipment, even before the outbreak of war in Europe, an increasingly difficult problem for the Chinese Air Force. The Soviet Union had become after 1939 the main source of supply, a source cut off by her entry into war in June 1941. Recognizing a trend of events that ultimately would permit the Japanese to bomb Chinese targets at will, and convinced at the same time that the United States eventually would have to fight Japan, Chennault already had turned to the idea of recruiting for service in China an international air force that would include American planes manned by American pilots. The participation of German, Russian, and Italian airmen in the Spanish civil war offered a precedent for action against the Japanese; such action would provide, he believed, valuable experience for the Americans.10

Having secured the agreement of Generalissimo Chiang-Kai-Shek, Chennault returned to the United States early in 1941 with Gen. P. T. Mow of the Chinese Air Force. To the latter’s attempt to secure aid for a long-range program that would rebuild the Chinese Air Force, Chennault lent assistance, but he was more active in an effort to put across his idea of an international air force. In Washington he was aided by Chinese Foreign Minister T. V. Soong, and after preliminary discussions with the War, Navy, and State departments, Chennault presented the plan at the White House. There were, of course, arguments against the proposal, but the current trend of events argued strongly for it. The precedent in Spain might be dismissed as of doubtful validity, but to stand on the niceties of international law only to permit China to fall a complete victim of Japanese aggression was also a disturbing suggestion. The clinching argument was the inescapable necessity to provide aerial protection for the

Burma Road during the time needed for rehabilitation of the Chinese Air Force.

The way paved for an approach to the practical problems of recruitment, training, and equipment, it was decided to attempt in the first instance only the organization of a fighter group of American airmen. Subsequent experience more than demonstrated the wisdom of this decision in favor of a modest beginning. To Chennault, time was of the essence; only by recruiting well-trained pilots and ground crews would it be possible to put the group into operation with the speed required. For personnel of this qualification, no source existed outside the air arms of the Army and Navy, and there he found a natural reluctance to yield up experienced personnel at a time when rapid expansion in all arms and services created the most acute shortages. With the men themselves, caution seemed to outweigh the promise of adventure and attractive financial rewards until it was made clear that the venture was not without official sanction and that officers volunteering could be placed on inactive status without loss of seniority. The required 100 pilots finally were signed, together with about 200 ground-crew personnel, and by 1 July the first contingent of the American Volunteer Group was on the West Coast ready to depart. Contrary to expectation, it had proved easier to find the planes than to get the men. Current production of all late-model pursuits was insufficient to meet requirements of the American and British air forces which carried a higher priority; but 100 P-40B’s (Tomahawks that were considered obsolescent by the AAF and RAF) previously allocated to Sweden were released for the purpose and reached Rangoon in time for the opening of training there in September.11

To take care of some of the legal problems, the Central Aircraft Manufacturing Corporation, owned by Curtiss-Wright and the International Company of China, which operated aircraft manufacturing plants in China, acted as agents between the Volunteer Group and the Chinese government. The Volunteers signed a contract for one year with Central Aircraft to manufacture, service, and operate aircraft in China. Great Britain made available a training base at Toungoo in Burma, where final preparations for combat could be completed without danger of Japanese air attack.

Implementation of hastily devised plans presented its own special difficulties. No provision had been made for replacements, some resignations

occurred, and a lack of spare parts plagued early efforts. In November, Chennault reported that only 43 of the original 100 planes were serviceable and that only 84 pilots remained fit for combat duty.12 Some of the most critically needed equipment was sent by air, but interested parties in the United States met with little success in an attempt to procure additional recruits. Chennault would have to do with what he had. On the eve of war, the Air Staff had under consideration a proposal to reinforce the Chinese defenses of Kunming with Philippine-based planes of the AAF in the event of an anticipated attack on this terminal of the Burma Road.13

A cardinal feature of Chennault’s plan was to avoid commitment of his force until it had been thoroughly trained and never to commit it piecemeal. General Magruder had been instructed to lend every assistance against possible pressure for a premature commitment.14 But after 7 December 1941, Rangoon, chief port of entry in Burma for supplies reaching China over the Burma Road, came under the threat of Japanese attack; and in response to a British appeal, one squadron of the AVG was sent to Mingaladon on 12 December. During the following week, the other two squadrons were moved east to Kunming for protection of the cities of southwest China and for patrol of the Burma Road, now subject to attack from near-by fields in Thailand. There, the AVG pilots first entered combat when, on 20 December, they inflicted heavy loss on Japanese bombers attempting an attack on Kunming. Three days later, the P-40B’s at Mingaladon inflicted comparable damage on a formation of enemy planes attacking Rangoon.15

As the battle for Burma became increasingly bitter, Chennault adopted a policy of rotating assignments that would give each squadron brief periods of comparative relaxation at Kunming, where combat missions were somewhat less frequent and exhausting. He resisted pressure to commit the entire AVG to Burma and divided his planes so that in addition to collaboration with a small RAF contingent in defense of Rangoon, he provided patrol of the Burma Road and a measure of support for Chinese ground forces along the Salween River.16 The policy followed actually represented the piecemeal commitment he had planned to avoid; but it enabled him to assist in holding the port of Rangoon until some of the supplies stockpiled there had been moved out for shipment to China, to protect the Burma Road

during that movement, and to provide after the fall of Burma the nucleus of an American air unit that would fight on in China.

The planes in their operations followed closely, however, preconceived tactical patterns. Using a two-ship element in hit-and-run tactics, the pilots extracted the fullest advantage from the superior diving and level-flight speed of the P-40B, while nullifying the enemy fighter’s superiority in maneuverability and rate of climb by avoiding dogfights. Against his bombers they also used a diving attack, frequently coming out of the dive to strike the bomber from below. The ruggedness of the P-40 and its superior firepower, together with an emphasis on accurate gunnery, constant reliance on the two-plane element, and the valiant work of ground crews enabled the “Flying Tigers” to destroy an almost incredible number of the more fragile Japanese planes while sustaining minimum losses. Even when the enemy after his first experience sought to wipe out the RAF and AVG contingents in Burma by sending an overwhelming fighter escort with his bombers, the air discipline of the American pilots held and kept down their losses. More serious losses were sustained in strafing attacks on the airfields they used, but the Volunteers to the last managed to keep a few planes in condition and offered at least a token resistance to almost every enemy attack. By the end of February, however, Rangoon had become a shambles, and during the first week in March the AVG pilots withdrew to Magwe. Following a heavy enemy attack on Magwe, they retreated over the China border to a forward base at Loiwing, where the Central Aircraft plant had been converted into an overhaul depot.17 By the close of April the campaign for Burma was approaching its end, and the squadron was forced back to Kunming, where it joined the remainder of the group.

The Burma Road was now useless, and Chennault, who had been recalled to active duty in April and promoted to brigadier general, sent part of his force east to Kweilin and Hengyang. This deployment promised better protection for the exposed cities of unoccupied China, and a fuller opportunity for activity against Japanese air forces. The AVG for all practical purposes had long since become a part of the armed forces of the United States, and plans had been made for its incorporation into the AAF. But the AVG was a volunteer group in fact as well as name; many of its personnel had no former identification with the AAF, and upon the dissolution of the

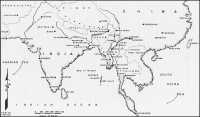

Map 23: China–Burma–India

organization they would enjoy a very real freedom of choice. Accordingly, at the request of the Generalissimo, formal action had been postponed until regular AAF units could be sent to assure continuity of operations.18 Meanwhile, a shipment of P-40E’s had been sent to Takoradi on the west coast of Africa, where they were assembled for ferrying to China. A few of these planes reached the AVG before the fighting in Burma had ended; others followed in May and June.19 And in the latter month, pilots of the 23rd Fighter Group,* which had been selected to replace the AVG, began to arrive under a plan to use them as replacements for the Volunteers until the new unit had built up sufficient strength to take over. There would be no break in the support rendered our Chinese allies by American pilots, however inadequate that support might be.

The Tenth Air Force

Meanwhile, in India the newly organized Tenth Air Force struggled with peculiar problems of command, mission, and impotence. On the collapse of the ABDA effort, it had seemed to Generals Brett and Brereton that Burma afforded perhaps the best opportunity for a continued resistance to the Japanese. Though Australia as well as Burma now was threatened, the latter presented the more immediate need for reinforcement. Tavoy had fallen to Japanese invaders as early as 19 January and Moulmein on 31 January; and as the enemy paused to bring up additional forces, Rangoon was the logical objective of a renewed thrust. An attack on Rangoon inevitably raised the question of continued supplies for China; and China, in addition to her own ability to engage the enemy, offered the promise of air bases within reach of sea communications upon which Japan’s victorious forces depended, and even within reach of Japan itself. As for the possibility that AAF bombers might make an immediate contribution to the defense of Burma, Brady (by then a brigadier general) had reported that heavy bomber operations against Bangkok and Saigon would be feasible from Akyab through use of Magwe and Toungoo as advanced bases.20

The objectives thus tentatively set at the time of Brereton’s departure from Java received support in Washington, where there was a keen awareness of the importance of aid to China. At the ARCADIA conference in January, it had been agreed that a high-ranking

* Pursuit units were redesignated “fighter” on 15 May 1942.

United States Army officer should be sent to the Far East to provide liaison between Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek and the ABDA Command, and early in February, Lt. Gen. Joseph W. Stilwell, who had once served as military attaché at Peking, received notice of his appointment as commander of U.S. Army forces in the newly created China-Burma-India Theater of Operations.21 Following the assignment of the recently activated Tenth Air Force to this theater, an advanced bombing detachment, known as FORCE AQUILA, was prepared under the command of Col. Caleb V. Haynes for a flight across the Atlantic and African routes to Karachi, with the eventual mission of bombing Japan from Chinese bases. Even as the end of resistance in Burma approached, plans were carried forward for another bombing project in China, one that was somewhat similar to Doolittle’s Tokyo mission in that there was provision neither for reinforcement nor replacement. Called HALPRO for its commander, Col. Harry A. Halverson, its departure was so delayed that it reached the Middle East during the crisis there in June, was pressed into service against the Germans,* and never reached the CBI.22 Colonel Haynes had reached India in early April, but with a force insufficient for, and under circumstances unfavorable to, the execution of his original mission.

The air force over which General Brereton assumed command on 5 March was largely an organization existing on paper. He had eight heavy bombers, the six brought up from Java and two B-17’s which had come in from Africa, eight bomber crews, and a few staff officers. The entire force was put to work three days later, not as bombers but as transports which from 8 to 13 March in an emergency operation transported 474 troops and 29 tons of supplies from India to Magwe in Burma, evacuating on the return flights some 423 civilians.23 Toward the close of this initial operation, reinforcements arrived from Australia, but instead of a fully equipped pursuit group, as expected, there were only ten P-40’s. Moreover, examination proved that most of the basic equipment of the units, including badly needed trucks, had been left in Australia, and for safety it had been considered necessary to send the ships around to the western port of Karachi.24 The British had evacuated Rangoon during the preceding

* In fact, the Halverson Detachment, together with the detachment flown in from India by General Brereton, formed the nucleus of the Ninth Air Force, which from 1942 to the fall of 1943 fought in the Middle East under Brereton’s command. (On HALPRO, see above, pp. 341–42.)

week, and Calcutta, chief port of India, had been rendered unsafe by enemy action on the periphery of the Bay of Bengal. The loss of all Burma seemed imminent, an invasion of India not unlikely.

Hope of substantial reinforcement, even the prospect of receiving the minimum administrative complement of an air force, depended upon a line of communications extending across the Indian and Atlantic oceans by way of the Cape of Good Hope, for Australia had need of all the limited resources available there. Moreover, the Japanese conquest of Java and the prior fall of Singapore had made the passage from Australia to India altogether too hazardous. The first convoy from the United States for India – carrying the Headquarters and Headquarters Squadron of the Tenth Air Force, the ground echelon of the 23rd Pursuit Group, the 3rd Air Depot Group, and personnel of the 1st Ferrying Group – was dispatched promptly enough on 19 March from Charleston, South Carolina. But with calls along the way at Puerto Rico, at Freetown, and at Capetown and Port Elizabeth in South Africa, this convoy would not reach India until mid-May.25

Fighter planes, meantime, had been shipped by water to the west coast of Africa for delivery by ferry to India. The first of them began to come into Karachi in April, but losses in transit were heavy and the planes themselves were destined ultimately for China.26 As for the sorely needed bombers, production was as yet unequal to the urgent demands of the several theaters, the expanding training program, the Navy, and our allies. Moreover, the ferry route across the Atlantic and Africa, still imperfectly developed and incompletely manned, exacted its toll of delay and loss en route.* There was an additional factor of misunderstanding between Washington and the theater, attributable to the inadequacy of communications and the unavoidable confusion which marked the first months of war, as to the number of planes actually on hand in India. Thus, War Department records indicated in mid-March that eighty P-40E’s had been delivered by the Australian convoy, and that nineteen B-17’s had been reassigned from Java to India. It appeared, then, that the Tenth Air Force possessed in the 51st a full pursuit group and with the 7th the equivalent almost of one equipped heavy bombardment group, when actually there were only ten P-40’s and the B-17’s were for the most part strung along the ferry route awaiting repairs or spare parts.

* See above, pp. 339–40.

Similarly, misunderstanding developed regarding the movement of P-40’s for the 23rd Group. In the absence of exact information as to the rate of their progress across Africa, the War Department was inclined to assume that unreported planes had reached India, when many were stopped along the way, some of them wrecked beyond repair and others requiring a major overhaul before they could continue. Even when a plane had arrived at Karachi, its engine was probably burned out and would have to be replaced – at a time when aircraft engines were almost as scarce as the aircraft themselves.27

Exact figures for this early period are virtually impossible to establish. But the whole story can be put in a capsule: in June, General Brereton left for the Middle East with virtually the entire striking force of the Tenth; in so doing, he took out the approximate equivalent of the tiny force of which he had assumed command four months before; and in the interval it had been possible to conduct operations only on the most meager scale.

In March, the impending loss of all Burma and the threat to India itself had resulted in the selection of Karachi as a port of entry and a center for the preparation of incoming organizations. Located on the western side of India, it was free, for the moment at least, from the threat of enemy interference and was advantageously situated with reference to air and water routes upon which operations in the CBI would be chiefly dependent. To General Brady was assigned the responsibility for establishing there a reception, classification, and training center that eventually, together with the installations of the Air Transport Command, became one of the major centers of AAF activity in the East.* 28 Brig. Gen. Raymond Wheeler, of the Services of Supply, came there from Iran to undertake, while preparing plans for theater supply, improvement in the docking and storage facilities of a port hitherto not fully developed.29 Meanwhile, the several hundred AAF personnel who had recently arrived from Australia gave their attention to the completion of a partially prepared British encampment for their own occupancy and to the inauguration of a training program. There was plenty to do, but morale inevitably reached an unusually low ebb. A thousand miles from the battle in Burma, their handful of planes was held in anticipation of enemy moves which might include attacks on the western ports of India; yet there were not enough aircraft even for training. Pilots and crews

* See above, p. 333, [.340 p. 340.

who had lost their edge on long sea voyages grew more stale as they awaited their turns with the few planes on hand. Shortages of tools and other equipment were acute. The men lived in an area barren of trees and grass on the edge of the Sind desert, from which sand and dust provided a well-nigh constant annoyance. Rations were British. Reading matter, cigarettes, candies, beer, and ordinary post exchange supplies were unobtainable. Worst of all was the lack of mail. Having been constantly on the move, most of the men had received no news from their families since leaving the United States in December or January.30

General Brereton located his own headquarters at New Delhi in order to be near the several British authorities with whom he would have to deal, and there in March he held a series of conferences on some of the larger questions pertaining to the establishment of the Tenth. The critical shortage of shipping directed the attention of the conferees particularly to resources available in India, for it was evident that a policy of living off the land would have to be followed insofar as it was possible. There were delays because of the necessity for coordination of action with both London and Washington, but the discussions progressed smoothly and prepared the way for successful collaboration in the implementation of policies which over the ensuing years assured, under the provisions of reverse lend-lease, substantial assistance for the Americans.31 Fortunately, in April a technical mission headed by Mr. Henry F. Grady arrived from the United States for a comprehensive survey of Indian resources with reference to the needs of American forces, and it thus became possible for General Brereton to concentrate on pressing matters of a more strictly military nature.32

Already Brereton had passed on to AAF Headquarters the benefit of his firsthand experience with combat units in the Philippines, Australia, and Java. While recognizing the critical need which had forced the sending out of imperfectly trained units even before the outbreak of hostilities, he now urged that personnel be fully trained and equipped before shipment overseas, whatever cost of delay in forwarding reinforcements might be entailed.33 His suggestions Included detailed recommendations for training and improvement of equipment and tactics.34 For his own force, he pleaded especially for medium bombers. Limited target areas located at distances which precluded the use of fighter escort, the lack of reconnaissance and photographic

units, and unfavorable atmospheric conditions combined to make high-altitude bombing of questionable value and argued for the superior speed of the mediums. The supply at the time, however, was unequal to the demand, and only in late April was it agreed, in partial concession to his continued requests, that the 7th Bombardment Group should be converted into a composite group of two heavy and two medium squadrons, the latter to be equipped with B-25’s.35 Not until July did the B-25’s arrive in sufficient numbers to permit commitment of one of the squadrons to combat. He also sought fighters superior to the P-40, and received the promise of P-38’s at some indefinite time in the future.36 But the Tenth would get along with the P-40 for more than a year, and for a while yet with few of them.

Although General Brereton had brought out of Java a few key personnel for the new air force, there were several important posts for which no qualified men were available. Consequently, one of his first acts after assuming command had been to radio Washington asking assignment from the staff of the North African mission in Egypt of Col. Victor H. Strahm to be his A-3 and Brig. Gen. Elmer E. Adler to establish an air service command. The assignment of Strahm was promptly approved, but some delay was experienced in securing the transfer of General Adler, who as chief of the air section of the North African mission since the fall of 1941 had gained a variety of experience which made him especially well qualified to undertake the planning and establishment of air services in the new theater. Not until 26 April did he arrive in India. With him came Lt. Col. Reuben C. Hood, Jr., and Capt. Gwen Atkinson, and on 1 May, with only Adler, Hood, and Atkinson on hand, the air service command was activated.37 Until the arrival of the convoy from America two weeks later with supplies and additional personnel, the command remained in effect a small planning staff.

Meanwhile, to Brereton’s chief of staff, Brig. Gen. Earl L. Naiden, had fallen the task of planning an air transport service from India to China, a problem that took on increasing significance as the Japanese pressed forward in Burma. Foreseeing the loss of Rangoon, the War Department had directed Brereton shortly after his arrival in India to survey an air route for the movement of supplies from India to Chunking.38 At the time, it was felt that central and northern Burma could probably be defended; and so the problem appeared to be that of providing for an air lift of supplies from Assam in the

extreme east of India to bases in Burma for transfer to Chungking by land transport. General Naiden’s survey indicated that the normal run should be between the RAF base at Dinjan and Myitkyina, with occasional runs as far as Yunnanyi after the monsoon was spent. There was only one airdrome suitable for the purpose at Dinjan, where three would be required, and the unusually heavy rainfall of the region left little prospect that the additional fields could be made ready before fall. A field at Myitkyina could be put in satisfactory state by 15 May, and two others could probably be completed by November. With these limitations, he doubted that more than twenty-five planes could be operated, and he anticipated that the service would be uncertain during the approaching rainy season.39

Though the Americans had not yet had time to explore thoroughly the idiosyncrasies of the Indian transportation systems, it was already evident that they must depend upon air transport between Karachi and Dinjan hardly less than from Assam to Burma. Accordingly, by the end of March, General Naiden had drafted plans for two transport commands: the Trans-India would operate between Karachi and Dinjan, and the Assam-Burma-China would run from Dinjan to Myitkyina and occasionally to Loiwing under a plan to extend the service in time to Kunming and Chungking. Col. Robert Tate eventually assumed command of the Trans-India operations. Colonel Haynes, then en route to India with a flight of transports and bombers, was chosen for the other command.40 Pending Haynes’ arrival, Col. William D. Old proceeded to Dinjan during the first week of April on assignment as executive officer and to take charge of preliminary arrangements.

His first immediate task, aside from the routine of providing quarters and supplies for personnel, was to assist in the delivery of 30,000 gallons of aviation gasoline and 500 gallons of lubricants to China for the use of Colonel Doolittle’s Tokyo raiders, then already at sea aboard the Hornet.* Ten Pan American DC-3’s from the trans-African contract services had been made available to haul the gasoline, of which 8,000 gallons were in Calcutta, where the tactical situation demanded that it be moved immediately. There was not enough storage space at Dinjan, and so two of the transports on 6 and 7 April hauled the fuel from Calcutta to Asansol in western Bengal, whence it was subsequently transferred via Dinjan to China.41

* See above, pp. 438–44.

Colonel Haynes arrived at Dinjan to assume his new duties on 23 April. With him was Col. Robert L. Scott, who had flown out in the same flight from the United States, and they were joined at Dinjan by Col. Merian C. Cooper. The task confronting them, to say the least, was discouraging. Although the equipment of the Americans was limited to thirteen DC-3’s and C-47’s, the single airfield already accommodated two British squadrons and was so crowded as to make proper dispersal of aircraft impossible. While barracks were under construction, the men were housed in mud and bamboo bashas with dirt floors. Messing facilities were poor; the quality of the food worse. Quartered more than ten miles from the airdrome, the Americans depended entirely on the British for ground transportation.42 Even more disconcerting was the absence of anything approaching an adequate defense against air attack by the Japanese. A single British pursuit squadron operated without benefit of an air warning system, and there were no antiaircraft guns.43 To avoid the probably disastrous effect of a sudden attack, the Americans undertook to get their planes into the air by dawn, and all servicing and cargo operations for planes landing during the day had to be handled with the utmost expedition. Under these circumstances, ordinary working hours were out of the question. The men generally worked from long before daybreak until late at night.44

The command had begun operations at a crucial point in the Japanese campaign for Burma. Following his capture of Rangoon, the enemy had grouped forces for a drive on Mandalay, key city of central Burma. General Stilwell, commanding the Chinese Fifth and Sixth armies, joined the British in an attempt to establish an effective line of defense. But by 25 March the Japanese had passed beyond Toungoo, by 2 April had forced the evacuation of Prome, and thus compelled the Allied forces to abandon their first line of defense. Their withdrawal to the north turned into a full retreat, and then under incessant pressure from the Japanese into a rout. Unable to challenge seriously the enemy’s supremacy in the air, meager RAF and AVG forces withdrew. During the last week in April, Lashio, railhead for the Burma Road, fell; and by the opening of May, Mandalay had been captured. The campaign drew quickly to a close. On the 6th the Japanese made their position in the southeast secure by taking Akyab on the Bay of Bengal, the point originally selected by General Brady as a base for American bombers. The following day

they moved into Bhamo, and on 8 May the enemy climaxed his northward drive by capturing Myitkyina, key base in the current plan for maintaining an air cargo line to China. With this defeat, Allied resistance on the ground for all practical purposes ended, the AVG squadron withdrew to Kunming, and Stilwell began his famous walk out of Burma.

To the Allied defense against this drive, the Tenth Air Force had been in no position to make a direct contribution. Conferring with Stilwell on 24 March at Magwe, near the current fighting, Brereton had reported that his air force would not be ready for combat for another month, an estimate which proved in fact to have been optimistic. Its assistance in combat was necessarily limited to the indirect aid provided by a few bombing missions which, considered either individually or collectively, can be regarded as having little more than a nuisance value.

The first combat mission of the Tenth was flown on the night of 2 April. Brereton planned two missions for that date, one against the Rangoon area and another against shipping targets in the region of the Andaman Islands, where a Japanese fleet that included carriers was reportedly assembled for an attack on Ceylon. At Asansol one of the two B-17’s assigned to the Rangoon mission cracked up on take-off with loss of its entire crew, and though the second took off well enough, it was forced by mechanical failure to turn back to base before reaching the target. That night the second mission, led by Brereton in person and flown by two B-17’s and one LB-30, successfully attacked enemy shipping near Port Blair in the Andaman Islands. Having dropped eight tons of bombs from 3,500 feet, the crews claimed hits on a cruiser and a transport. Antiaircraft fire both from the ships and from batteries on shore was encountered, and the planes subsequent to the bombing were attacked by enemy fighters. Two of the bombers received damage, but all returned to base.45

At General Stilwell’s insistence, the Tenth thereafter devoted its attention to the Japanese in Burma.46 On 3 April six bombers took off from Asansol to strike at docks and warehouses in Rangoon. Incendiary and demolition bombs were used to start three large fires; no resistance from enemy pursuits developed; one B-17 was lost on the return trip, cause unknown.47 By 16 April the planes had been put in good enough shape to send again six bombers to Rangoon. Having taken off this time from Dum Dum near Calcutta, they first dropped

flares to illuminate the target and then unloaded forty-two 250- and 300-lb. bombs. No enemy fighters challenged the effort and heavy flak was evaded, but numerous searchlights made it impossible to estimate the results of the bombing. Once more, on 29 April, a flight of bombers hit the docks at Rangoon with 500-lb. bombs. The enemy put up interceptors and antiaircraft fire, but all planes returned without damage.48 On the nights of 5 and 6 May, the bombers struck at Mingaladon, former RAF airdrome near Rangoon which the Japanese were using as a base for interceptors. On the night of the 5th, two flights of two B-17’s each scored hits on a hangar and parked planes; it was estimated that forty planes had been destroyed and twenty-five damaged, but searchlights, antiaircraft fire, and attacking enemy fighters made accurate observation difficult. On the following night, three B-17’s scored a direct hit on a fuel dump. On the night of 9 May, six B-17’s engaged in a joint attack on Mingaladon and the Rangoon docks. Though attempted interception by the enemy failed, it prevented accurate observation of bombing results.49

At this point, attention was drawn from Rangoon by the capture on 8 May of Myitkyina. Recently counted upon as a key base on the air route to China, its airfield now represented a serious threat to the whole air cargo project. Dinjan lay within easy range of fighters based at Myitkyina, and until more adequate provision could be made for the defense of Dinjan, Myitkyina became a target of prime importance to Tenth Air Force bombers. The heavies ran their first mission in direct defense of the air cargo line to China on 12 May when four B-17’s, flying from Dum Dum, heavily damaged the runways and fired several parked aircraft in a daylight attack on Myitkyina airfield. Two days later the attack was repeated with further damage to runways and the destruction of several buildings. After another two-day interval, a third attack followed. Reconnaissance after the mission revealed no signs of activity at the airdrome, which for a time at least was in an unusable state.50

To the transport pilots themselves had actually fallen the most dramatic role for American airmen in the attempt to defend Burma. Pressed immediately on arrival at Dinjan into emergency deliveries of ammunition, fuel, and supplies to the Allied forces in Burma, they brought out on the return flights an increasing number of wounded troops and civilian refugees. When after the fall of Mandalay it became obvious that Myitkyina and Loiwing were also doomed, Army

pilots began to ignore the normal load limits. Planes built to carry twenty-four passengers often took off with more than seventy. Some of the civilian pilots vigorously opposed the practice at first, but after seeing military pilots flying incredible loads without mishap, they too revised their estimate of the capabilities of the planes and joined wholeheartedly in the effort. In the process, the DC-3 and its Army equivalent, the C-47, established a lasting reputation for dependability and durability under the most adverse flying conditions.51

Both Haynes and Old took regular turns as pilots during these emergency operations. All crews were badly overworked, but not a plane was lost, though the unarmed craft were completely at the mercy of possible interception by the enemy. As Allied defenses in Burma crumbled, the emphasis on cargo transport gave place to one on evacuation of personnel, and in a series of hairbreadth escapes most of Stilwell’s staff was flown out to India.52 After the general himself elected to remain and walk out with what was left of his command, the transports dropped food and medicines to his columns on their slow trek to safety. On 21 May, Stilwell reached a village near the Burma-India border, whence he proceeded by air to Dinjan for conference with Generals Wavell, Brereton, and Naiden; and the major part of the air transport operation was over.53 But for the assistance of columns which had chosen to move northward, food and supplies continued to be dropped whenever possible; and after it became apparent that the Japanese would not take Fort Hertz, one of the DC-3’s successfully landed on a field reputed to be less than a thousand feet in length and took off with a load of disabled Ghurkas. The strip eventually was lengthened to render landings and take-offs less hazardous, and Fort Hertz assumed importance as a way-stop on the India-China transport line.54

Questions of Command and Mission

The rapid Japanese advance through Burma had long since called into question most of the assumptions upon which original plans for the Tenth Air Force had been based. The Tenth now faced the question of whether its mission, at least for the time being, should be limited to the defense of India – indeed, whether there was much point in thinking of support for China until India had been made secure against threatening forces in Burma, the Bay of Bengal, and the Indian Ocean. In any case, it was clear that earlier concepts of air

transport operations for the movement of supplies to China had been overly optimistic; the crucial air link in the supply line would have to be longer than had been anticipated, and plans would have to be revised to take into consideration new operational hazards and a heavier demand for equipment and personnel. There were other questions of similar import and difficulty, but all of them tended to turn on a basic question of mission which had become involved in a somewhat complex problem of command.

Command difficulties had first arisen with the flying of the Tenth’s initial combat mission on 2 April. At the conference between Stilwell and Brereton late in March, it had been agreed that the air force when ready would be used in support of Allied forces in Burma. General Stilwell consequently received with some surprise the news of the Andaman Islands mission; and General Brereton, who regarded the function of the heavy bomber as distinct from that of air-ground support, was similarly surprised to receive a prompt request from the theater commander for a report on the capabilities of the air force in order that he might plan for its use in support of critical ground operations.55 The mission itself had been flown against enemy forces whose threatening position with reference to India and Ceylon caused the British to propose to Washington a close coordination of defensive efforts between the Tenth and the RAF, and on 15 April the War Department informed Stilwell that the American air force would be used in the Bay of Bengal and Indian Ocean area north of Ceylon in conformity with British plans.56 But General Stilwell, fearful of the interpretation that might be placed on the action by the Chinese, protested a decision made without reference to him as theater commander and meanwhile withheld the appropriate orders to Brereton.57 And so when the latter, who had been informed of the War Department message to Stilwell, was shown a message from the Air Ministry in London confirming the agreement and urging that it be put into immediate effect, he had little choice but to seek direction from the War Department, pointing out that he lacked instructions either from Washington or the theater. In reply, he promptly received a directive to cooperate with the British as requested.58 But while this served well enough to clarify his immediate responsibility, it left a delicate problem of his relation to the theater command.

If there were elements of the comic opera in the continuing exchange of messages which preceded a general understanding that the

Tenth – whose largest mission to date comprised a total of six bombers would remain under theater control but with instructions for the time being to cooperate with the RAF,59 the exchange also revealed some of the extraordinary perplexities of the CBl that would add to the story of air operations in that theater an unusually complex chapter on administration. There was no escape from the necessity to base in India any effort for the support of air operations in China, and thus no possibility of indifference to the security of India itself. Yet, the forces available were wholly inadequate for either mission, and they necessarily served chiefly as a token of intent. Changes thus tended to acquire a significance altogether out of proportion to the forces involved. Fortunately, the fear of enemy domination of the Indian Ocean was soon eased by indications that the Japanese fleet was withdrawing its units to Singapore, that Port Moresby in New Guinea rather than Ceylon was the enemy’s next objective, and by the British landing at Madagascar on 4 May, which coincided with the enemy withdrawal after the Coral Sea action. Accordingly, on 24 May the order committing the Tenth Air Force to operations under RAF supervision was rescinded by the War Department in a message to General Stilwell, who promptly replied that it would be recommitted to a mission primarily in support of China.60

Thus the mission of the Tenth Air Force remained as it had been originally fixed, but that mission still presented its own peculiar problems of command. General Stilwell’s responsibilities argued for the location of his headquarters at Chungking, while practical considerations indicated that Brereton’s headquarters should be in the base area of India. At the same time, it was evident that the principal combat effort of AAF units in the CBI must be made in China. Hundreds of miles and imperfect communications consequently separated the two American headquarters, and, similarly, the ranking air headquarters would be far removed from the principal area of combat operations. Some of the difficulties inherent in this arrangement already had been indicated. When in March it became known that only ten P-40’s were carried by the convoy from Australia, General Brereton sought the assignment to the Tenth of the pursuit planes destined for the AVG by way of Africa and Karachi, only to be turned down by the War Department.61 Thereupon, he suggested that the AVG immediately be inducted into the AAF and be assigned as a pursuit group under Chennault’s command, to the Tenth Air Force.62 Induction of the

AVG had already been agreed upon, but subject to the provision of a full American pursuit group in China;63 and on 10 May the War Department informed Brereton that the 23rd Pursuit Group, scheduled to replace the AVG, would not be assigned immediately to the Tenth.64 At about the same time he learned that HALPRO, as a special bomber project, would operate in China independently.65

At this point, General Stilwell intervened to avoid the administrative inconvenience and embarrassment that would arise from the independent operation of two groups, each of them larger than the entire combat strength of the theater’s air force. On 17 May he notified the War Department that, subject to further instructions from Washington, the Tenth Air Force would have charge of all preparations for reception of HALPRO, which would be assigned to the Tenth upon its arrival in the theater, and that Brereton’s headquarters would control the induction of the AVG and command the 23rd Group after the induction.66 And this was the policy destined ultimately to prevail.

The AVG contracts were due to expire on 4 July, and the induction into the AAF of such of its personnel as so elected was set for that date. It was planned to place in China by that time a small force of medium bombers in addition to the 23rd Group, whose elements as they arrived in the theater moved forward to come under the command of General Chennault.67 In recognition of the geographical distance separating China from India and of General Chennault’s experience and prestige, AAF fighter and bomber units in China would be organized into the China Air Task Force (CATF) assigned to the Tenth and commanded by Chennault.68 The date for its activation also was set for 4 July.

Meanwhile, AAF detachments moved into China during May and June in preparation for the change-over. The movement of personnel and equipment was unavoidably slow and difficult, and not without disappointment – even tragedy. The first flight of B-25’s earmarked for the CATF reached Dinjan on 2 June with Maj. Gordon Leland commanding. It was planned that on the following day the flight would be completed to Kunming after a bombing of Lashio en route. The planes belonged to the 11th Bombardment Squadron (M), recently assigned to the 7th Group and detached for service in China. In the face of an unfavorable weather report and against the advice of Colonel Haynes, the six planes took off early the next morning. They

unloaded their bombs on the Lashio airfield, but subsequently three planes – including that of Major Leland – crashed into a mountain side while flying through an overcast at 10,000 feet, and another plane was abandoned when it gave out of gas near Chanyi. Only two of the aircraft landed at Kunming, one with its radio operator who had been killed in a brush with enemy fighters.69 Six other B-25’s led by Maj. William E. Bayse, veteran of the Java campaign, arrived at Kunming without mishap during the next two weeks.70 Some of the pilots had participated in the Doolittle attack on Tokyo.

Movement of the P-40’s from Africa continued to be slow, and the induction of the AVG, from the first a perplexing problem, proved disappointing in its results. It had been hoped that the transition might be made without serious loss of personnel or reduction in the effectiveness of an organization which had so well demonstrated its fighting ability. Several weeks before induction was scheduled to take place, however, it had become obvious that only a few of the men could be retained. War-weary and eager to visit their homes before undertaking another long period of foreign service, they desired immediate leaves which the induction board was not authorized to grant. Some preferred to take remunerative positions with the China National Airways and Hindustan Aircraft companies rather than accept the grades offered them by the Army; many formerly belonged to the Navy or Marines and preferred to return to those branches of the service; some expressed resentment over the manner in which the induction was handled; and a few were not able to pass the required physical examination. Eventually when the induction board, presided over by Chennault and made up largely of Tenth Air Force officers, completed its canvass of the personnel, they found that only five pilots and a handful of ground men had chosen to stay with the AAF in China. Approximately twenty of the pilots agreed, however, to remain on duty until further replacements could arrive, and one of them lost his life in combat during this extra tour.71

Activation of the CATF on 4 July 1942 marked an important turning point in the war in China. But the AVG as it now passed into history had set the pattern for subsequent air operations in that theater, and its score of almost 300 enemy planes destroyed at a cost of less than 50 planes and only 9 pilots provided a challenging record for its successors.72

Meanwhile, uncertainties existed regarding the control of the air

supply line upon which operations in China depended. Upon being informed early in March that development of the air ferry* to China would be a responsibility of the Tenth, General Brereton had requested that ferrying personnel and equipment sent to the theater be assigned to the air force. Brig. Gen. Robert Olds of the Air Corps Ferrying Command objected on the ground that such an arrangement would result in diversions from the transport service to combat organizations.73 Brereton having renewed his request on 9 April, the War Department replied that policies relating to the movement and supply of planes would be administered throughout by a central office in Washington, but that insofar as ferry operations were affected by military developments in India the control would be exercised by Brereton. To this rather ambiguous explanation there was added the information that the air freight service from Assam to China would be operated by the 1st Ferrying Group under the control of Stilwell.74 General Arnold, after Brereton had indicated a continuing concern over the uncertainties and confusion of command responsibilities,75 attempted to clarify the problem in a message to Stilwell which declared that Brereton held responsibility and authority over aircraft between Karachi and Calcutta, while General Stilwell would control aircraft designated for service to China. The latter was also vested with authority to change the location of operating stations and ferry control detachments in both India and China. It further was promised that an officer who fully understood ferrying operations would be provided for Brereton’s staff.76 The general statement of policy, however ambiguous it seemed at the time, at least provided a principle of action which, with the passage of time and a better understanding by all parties concerned, permitted the development of a centralized control of strategic air services while not entirely ignoring the normal prerogatives of a theater command in the event of an extreme emergency. But the administrative division between trans-India and India-China operations ran counter to the arguments of experience soon gained in operating the service.

During his incumbency at Dinjan, Colonel Haynes had discarded

* Originally the term “ferry” was used in the CBI to describe organizations more largely concerned with air transport operations than with the ferrying of aircraft. It is possible that some of the misunderstandings which developed stemmed from this loose usage, which in turn reflects the general difficulty experienced in clarifying the many problems arising from this new type of air operation. (See above, Chapter 9.)

in effect the original plan for separate operation of the Trans-India and Assam-Burma-China lines. Manpower and storage space at Dinjan were unequal to the demands of a plan requiring transfer of cargo, and frequently Trans-India planes were sent on into Burma and China. Eventually, the two transport commands were merged as the India-China Ferry, which continued until the Air Transport Command took over in December 1942. Haynes was transferred to China in June for command of the bombers in the China Air Task Force, and Scott quickly followed under a similar reassignment for command of the fighters. Colonel Tate, commander of the Trans-India Ferry, subsequently took command of the India-China Ferry.77

Despite uncertainties that would not be fully clarified for another six months, the pioneering pilots and transport aircraft of the Assam-Burma-China Ferry had shown the way for the famed “over the Hump” service that would follow. Although the volume of freight hauled had not been great, it had been carried under the most trying circumstances and with a degree of success which encouraged the continuation of plans that would depend upon air transport to a much greater extent than had been originally considered. Cargoes included passengers, gasoline, oil, bombs, ammunition, medical supplies, food, aircraft parts, a jeep, and two disassembled Ryan trainer aircraft. More than 1,400,000 pounds were moved eastward from Dinjan, and approximately 750,000 pounds were brought west on return trips.78 And in addition, the men and planes had explored the possibilities of troop-carrying and supply-dropping over Burma – services destined to prove the key to victory in a successful reinvasion of Burma two years later.

Meantime, the arrival in mid-May of the convoy from the United States had permitted substantial progress toward the establishment of a service command. In addition to needed supplies, it brought the 3rd Air Depot Group. Already Agra had been chosen as the most desirable location for the main depot, and negotiations for allocation of the site were completed by 19 May. On 28 May the air depot group arrived there to establish the 3rd Air Depot, with Col. R.R. Brown as depot commander and Lt. Col. Isaac Siemens in command of the group. For a time the men lived in tents, while awaiting completion of barracks. Construction work depended heavily on native labor and, in the absence of enough heavy machinery, progressed slowly. American mechanics and aircraft specialists of various sorts doubled as

carpenters, ditch diggers, and at whatever other tasks needed to be done. There was work for all at Agra; and this, plus the evident progress made, prevented development of morale problems comparable to those existing earlier at Karachi.79

The service command would serve both India and China. To assist in carrying out this large mission, the 59th Matériel Squadron (soon redesignated 59th Service Squadron) was divided into small base units to serve the needs of combat stations. The unit’s headquarters was located at Allahabad, selected as base for the heavy bombers, and there, too, was stationed Base Unit Number One. Other base units were assigned to Kunming, Aura, Dinjan and Chabua, Chakulia, and Bangalore, the latter being the location of Hindustan Aircraft, Ltd., which was to be changed over by agreement with the British from a manufacturing plant to a repair, and overhaul depot for American-made aircraft.80 During May additional personnel for the service command arrived and received assignments. On 23 May, Lt. Col. Daniel F. Callahan was made chief, maintenance and repair division, and the following day Col. Robert C. Oliver reported to become chief of staff to General Adler, Hood taking the assignment as chief, supply division. No headquarters and headquarters squadron was created, personnel normally constituting such an organization being assigned to the Tenth Air Force and detailed to duty with the service command.81

By late June, Adler’s infant command was beginning to function in the routine fields of receipt, storage and issue, distribution, maintenance, repair, overhaul, and salvage. Other duties requiring attention were local procurement, manufacture of certain items, and various responsibilities in connection with maintenance and repair work, which by that time had begun at the Hindustan plant at Bangalore. The command suffered with other organizations the common difficulties of the theater at this time-poor communications, shortage of motor vehicles, dependence upon unskilled or semiskilled native labor, and always the weather.82

The combat force of the Tenth proper was still limited to a handful of heavy bombers, some of them badly worn. Its combat operations continued, therefore, on the scale set by its earlier missions to Burma. Turning on 25 May from its effort to assure the neutralization of Myitkyina airfield, it struck again that night with five B-17’s at targets in the Rangoon area. One of the planes was forced to turn

back, two were damaged.83 Attacks on Myitkyina were resumed on the 29th, when four planes bombed from 23,000 feet. The following day a similar attack was made, but as no enemy activity was in evidence on either occasion the attacks were discontinued.84 During the first week of June, the small force undertook its final flights over Burma before the weather and a shortage of spare parts combined to ground the last of them.85 Five planes attacked the Rangoon docks and harbor area on 1 June, reporting that one tanker had been sunk and that another had been left listing.86 Three days later, two bombers struck at the same target area without observing the results; attacked by ten fighters, one plane was destroyed, another seriously damaged.87 And this was the last until the monsoon lifted.

Brereton’s Departure for the Middle East

By mid-June, when the monsoon had come, the Americans were beginning to appreciate the magnitude of the task involved in establishing and operating an air force in Asia. The report of the Grady mission, plus three months of experience gained by the Tenth, had revealed that even for a small force the logistical problem was staggering. Unable to use the more direct routes through the Mediterranean and across the Pacific, and forced to sail in convoys for protection against enemy submarines, ships from the United States required two months to make the 13,000-statute-mile voyage. Furthermore, the demands of more active theaters for cargo ships, transports, and escort vessels were so heavy that bottoms allotted to Asia were kept to the barest minimum.88 And after the ships reached India the logistical problems were by no means at an end. Japanese naval and air action in the Bay of Bengal restricted the use of Calcutta and forced incoming ships to dock along the west coast, where only three ports of any importance were available – Cochin, Bombay, and Karachi. Cochin was entirely too far south to serve as an American port of entry; Bombay was overtaxed with British shipping. Hence, although heavy port equipment had to be imported and existing storage space greatly enlarged, the original choice of Karachi had been confirmed by subsequent study.89

Had it been possible to use ports on the eastern shore, a third important problem might have been less troublesome; but dependence on Karachi forced a maximum dependence on the Indian railroads. Outside northwestern India, the railway system was not highly developed,

and by American standards was grossly inefficient throughout. Four different gauges of track required numerous extra handlings of freight by slow-moving, physically weak native laborers. In eastern India, further delays were imposed by the use of ferries instead of bridges for crossing numerous streams; on the important Calcutta-Assam line of communications, there existed not a single bridge over the Brahmaputra River and its tributaries. The railways, already weakened by a transfer of locomotives and rolling stock to Iran and forced now to haul the products of the industrial centers of eastern India which normally went by sea from Calcutta, were unable to absorb American traffic without countless breakdowns and heartbreaking delays. After a two-month voyage from the United States, equipment generally took six additional weeks in moving from Karachi to Assam. For goods to reach Kunming from Karachi, unless entirely carried by air, it generally took longer than the voyage from the United States.90 The highway system, which was in even worse condition than the railroads, could not accommodate any, appreciable additional load. First-class, all-weather highways were rare, and even these generally were too narrow to permit two-way traffic. The best of them, too poorly graded and banked for efficient use by high speed vehicles, were frequently rendered impassable by monsoon rains.91 Initially, however, the inadequacy of the highway system hardly proved a major handicap, since very few trucks were available to the Tenth. Because river boats ordinarily carried a considerable volume of freight on the Ganges and Brahmaputra rivers, that means of transportation was not overlooked in the early planning, and especially in plans for the movement of cargoes between Calcutta and Assam. Unfortunately the river-boat fleets, like rolling stock, required extensive replacements. Moreover, the railway system had not been planned to complement the riverways; main railway lines frequently paralleled the course of the rivers, and this was particularly true in eastern India.92 The communication system presented equally disturbing problems. Telegraph and telephone lines extended to practically every section of the country, but equipment and methods were hopelessly outmoded for military purposes.93

In setting up an air transport service for aid in overcoming these difficulties, still other problems were met. Existing airfields had been located and constructed primarily with a view to commercial rather than military needs. Runways were generally too short and too lightly

constructed for use by either speedy pursuits or fully loaded bombers and transports. Repair and maintenance facilities, in addition to quarters for personnel, had to be provided on existing fields, while strategic requirements called for the construction of many entirely new installations. Local materials and native labor had to be used, which proved another retarding factor.94

Another problem was the climate. India has been fittingly described as “too hot, too cold, too wet, too dry.” Excessive rainfall during the wet monsoon retarded construction and restricted operations; dust conditions during the dry season caused heavy wear on aircraft engines. In those sections of the country in which Americans were stationed, the greatest trouble arose from the effects of excessive heat and humidity on personnel. Reduced resistance as a result of the enervating climate tended to make them easy victims of the many endemic diseases. Only constant alertness could prevent malaria, typhus, cholera, heat rash, and fungus growths from seriously crippling the air force.95

Yet, by the end of June 1942 appreciable progress had been made in establishing the Tenth Air Force and preparing for postmonsoon operations. Approximately 600 officers and 5,000 enlisted men were on hand, while aircraft strength had increased sufficiently to permit a general eastward deployment of combat units. The 11th Bombardment Squadron (M), the 16th Squadron of the 51st Fighter Group, and the three squadrons of the 23rd Fighter Group were already in Kunming; headquarters of the 7th Bombardment Group had moved to Barrackpore, near Calcutta, while its two heavy squadrons, the 9th and 436th, were established at Allahabad; advance parties of the two remaining squadrons of the 51st Group were in Dinjan to prepare for the arrival of its air echelon; and the 22nd Squadron (M) was expected to begin operations from Andal at the end of the monsoon.96

But before June had run its course, the build-up of the Tenth received a serious setback. The Combined Chiefs of Staff had regarded the Middle East and Far East theaters as interdependent, and had stipulated that plans for their reinforcement should remain flexible in order that units might be shifted on short notice to whichever area appeared to have the greater need.97 And now in Africa, Rommel again had the advantage over the British, was indeed in position to challenge the whole Allied cause in the Middle East. Consequently, on 23 June, General Brereton received orders to proceed to the

Karachi Air Base, 1942

Middle East with all available bombers and to assume command of American forces there for the assistance of the British.98 He was authorized to take with him all personnel necessary for the staffing of a headquarters, and all cargo-type planes required for transportation. Further, he was instructed to appropriate whatever supplies and equipment might be needed from India-bound cargoes passing through the Middle East.99 Three days later he left India, taking with him General Adler, Colonel Strahm, and several other key officers,100 and he was soon followed by the planes and crews of the 9th Bombardment Squadron (H).101 The most dependable ferry pilots were selected to transport ground personnel and equipment for the bomber detachment.102

General Naiden, Brereton’s successor in command of the Tenth Air Force, was left with a crippled air transport system, a skeleton staff, and virtually no combat strength outside the task force in China. The future of the Tenth, and with it the extent of our continuing aid for China, now depended on the news from the Middle East.