Chapter 14: Transportation in the Pursuit

The Railways

At the end of July the main concern of the logistical planners had still been the threatening deficit in port discharge capacity. That problem was no nearer solution in the first week of August. But the sudden expansion of the lodgment area brought with it an inevitable shift in emphasis. For the next six weeks transportation was the lowest common denominator of supply operations, as the Transportation Corps found it increasingly difficult to carry out the injunction which had become so familiar to all movement orders: “The TC will furnish the necessary transportation.”

With the extension of the lines of communications the railways at last began to play their intended role. They had moved only negligible tonnages in June and July, in part because rail operations were uneconomical over short distances, in part because Cherbourg, the terminus of the main line, was not yet receiving supplies in great volume. But the logistical planners always intended, and in fact deemed it necessary, that the railways bear the main burden of long-distance hauling, and with the deepening of the lodgment in August the way was finally opened for them to assume that task.

France possessed a good rail network, totaling nearly 26,500 miles of single- and double-track lines. Until 1938 it had been divided into seven big systems (two of them state owned). In, that year these were combined into a single national system known as the Société Nationale des Chemins de Fer Français. The densest concentration of lines was in the north and west, and. Paris was the hub of the entire network. In physical characteristics and method of operation the French system was similar to others on the Continent. In general, its equipment, including rolling stock and loading and unloading facilities, was light in weight and small in capacity, and it relied heavily on manual labor. Rolling stock built in the United States for use on the continental lines had to be specially designed.1

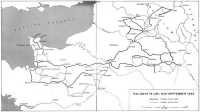

Although the OVERLORD logistic planners did not expect to have an elaborate rail network operating on the Continent in the first few months, they hoped to open at least one line along the main axis of advance. Plans had been made to rehabilitate a north-south line from Cherbourg via Lison Junction, St. Lô, Folligny, Avranches, and Dol to Rennes, where the first big depot area was expected to be established. From there one line was to be opened south and westward to the vicinity of Quiberon Bay, and a double-track line eastward from Rennes to Le Mans was to be reconstructed. (See Map 9.)

U.S.-built World War I Locomotives at the roundhouse in Cherbourg

At the time of the breakout at the end of July rail lines had been rehabilitated as far as tactical progress permitted. The main double-track line from Cherbourg to Lison Junction was in operation, a few branch lines in the Cotentin had been restored, and construction was about to start on two large marshaling yards south of Cherbourg in anticipation of the heavy shipments from that port.2

Railway operating units had been scheduled to enter the Continent via Cherbourg within the first three weeks of the landings. Because of the delay in opening the port, however, the first units were brought in across the beaches. They consisted mainly of the three operating battalions and two shop battalions which operated the existing lines under the direction of the 707th Railway Grand Division.

The movement of equipment was likewise delayed, and the first rolling stock, a work train consisting of a 25-ton diesel engine and ten flatcars, was mounted on heavy trailers, ferried across the Channel on an LST, and brought in across the beaches early in July. The movement of rolling stock to Cherbourg by train ferry, seatrain, and LST did not get under way until the end of the month. The seatrains Texas and Lakehurst brought in the first heavy equipment, including diesel and steam locomotives, tank and box cars, trucks, and bulldozers. Even then the condition

Gondola Rolling Out of an LST, specially equipped to carry rolling stock, Cherbourg, July 1944

of the port was such that the ships could not be berthed, and the heavy equipment had to be transferred to barges, transported to the quay, and then hoisted to the quayside tracks by crawler cranes.3 A large portion of the rolling stock was eventually ferried across the Channel in LSTs which had been fitted with rails.

The first important demand for deliveries by rail resulted directly from the Third Army’s forward lunge at the beginning of August. Rail transportation suddenly became economical and essential, for the long hauls to the army area immediately placed a heavy strain on motor transport. In anticipation of the need for rail facilities one engineer general service regiment was withdrawn from Cherbourg and put to work on the line running south from St. Lô immediately after the breakout from Avranches.4 Within a few days it was apparent from the speed of the advance that extraordinary efforts would be required to provide rail facilities in support of the army, and additional engineer regiments were therefore assigned to restore the lines south and east of Folligny. (Map 17)

The reconstruction of damaged rail lines could hardly keep pace with the advance of the combat forces. Nevertheless, every

effort was made to meet a request made by the Third Army on 12 August to open a line to Le Mans, where the army wanted delivery of approximately 25,000 tons of ammunition and POL within the next three days. The decision of 3 August by which the main effort was directed eastward rather than into Brittany made it desirable to develop other lines in addition to the one already planned. But much of the parallel line farther north, which ran from Vire eastward to Argentan and beyond, was still in enemy hands.

The line running southward to Rennes and then eastward could not be restored to operation quickly because of time-consuming bridging jobs at both Pontaubault, on the Sélune River south of Avranches, and Laval. Fortunately the condition of secondary lines made it possible to select an alternate route for temporary use pending the reconstruction of the main lines.5 The temporary route ran eastward from Avranches to St. Hilaire-du-Harcouet, south to Fougères, east to Mayenne, and then south to join the main line at La Chapelle. The reconstruction of even this route required several major bridging projects, the largest one at St. Hilaire,6 and beginning on 12 August elements of eleven engineer general service regiments were assigned to work on it.7 On 17 August, after many delays, the first of a scheduled thirty-two trains bearing supplies for the Third Army arrived at Le Mans.8

The first major movements of cargo via rail were carried out under something less than ideal conditions. Most of the route restored to operation thus far was single track, and there was virtually no signal system. Since two-way traffic on single-track lines was prohibited it was not long before congestion developed between Avranches and Le Mans. Meanwhile the inevitable shortage of empty freight cars developed at the loading points in the base areas.

The difficulties at Le Mans were aggravated by the severe damage to the yards. Here was a pointed example of the effect which Allied air bombardment could have on Allied ground operations, for the big terminal at Le Mans had been almost completely demolished by air raids. One roundhouse was completely destroyed, the other badly damaged, and the machine shop about two-thirds demolished. In addition there were the usual torn-up tracks and damaged locomotives. Lack of tools and equipment necessitated a high degree of improvisation. In the absence of a signal system, for example, flagging of trains during darkness was at first accomplished largely with flashlights, cigarette lighters, and even lighted cigarettes. Blacksmiths immediately went to work fashioning badly needed hand tools. Meanwhile, French railway workmen gradually began to appear with tools and missing parts from repair and maintenance machinery which had been hidden from the enemy. In some instances the men made use of spare parts that had been brought to France by the Americans during World War I.9

The condition of the Le Mans rail yards was typical of the destruction which the Allied air forces had inflicted on all important rail centers, junctions, and choke points in their efforts to isolate and prevent

Map 17: Railways in use, Mid-September 1944

[Map merged onto previous page]

enemy reinforcement of the lodgment area. Folligny had also suffered extensive destruction, and its yards were a mass of burned cars and twisted steel. Enemy destruction of rail lines, in contrast, was not extensive, and rehabilitation was much simpler than expected. In the demolition of bridges the enemy was more methodical, although even there the amount of damage was only about half as great as expected.10 Enemy-inflicted damage to equipment was also less than expected, and much rolling stock was captured and put to use. Nevertheless, the shortage of freight cars soon became a serious limiting factor because of the delay in moving equipment to the Continent and because of the losses resulting from Allied bombing of marshaling yards and locomotives. Destruction by the Allied air forces in fact threatened to have a more disastrous effect on the Allied logistic capabilities than on the enemy’s operations. Beginning late in June supply and transportation officials repeatedly asked that railway bridges, tunnels, and viaducts, whose repair entailed large expenditures of effort, be spared in the hope that the enemy would not destroy them in retreat.11

At about the time the first trains entered Le Mans the Allies completed their envelopment of the enemy forces in the Falaise area, making it possible to begin work on the northern line eastward via Argentan, Laigle, and Dreux. Reconstruction of that line was particularly important in view of the necessity of supporting an additional army over extended lines of communications, and the project was given a high priority.

The opening of the main route east of Rennes still awaited the reconstruction of a rail bridge at Laval.12 This was completed at the end of the month. Meanwhile reconnaissance parties had pushed on from Le Mans to examine the lines farther east. As could be expected, they found the railways between Chartres and Paris heavily damaged, for the Allied air forces had made special efforts to cut enemy lines of communications along the Seine. Once again, however, by circuitous routing it was possible to push a line eastward beyond Chartres. On 30 August the first American-operated train arrived at the Battignolles Yards in Paris, only four days after the surrender of the city. The opening of this line did not immediately permit heavy shipments to the French capital, however, and aside from engineer supplies, hospital trains, and civil affairs relief, little tonnage actually went forward.13 Most of the Seine bridges had been destroyed, and the Paris yards, which had only limited capacity at the time, provided only a narrow funnel for the supplies required beyond the Seine.14 By the end of the month the northern as well as the southern line was open to rail traffic, and Dreux and Chartres were for the moment at least to become the important railheads for the First and Third Armies respectively.15 The volume of traffic to these points was not initially large, however. Between 24 August and 2 September only seventy trains with slightly more than 30,000 tons were

dispatched from Le Mans to Chartres, and at the latter date the daily movements to Chartres were averaging 5,000 tons.16

The sudden need to rebuild the railways in August had made it necessary to augment greatly the work force employed in reconstruction and to reorganize the work of the ADSEC engineers. Until mid-August the Railway Division of the ADSEC Engineer Section directly handled all reconnaissance, planning, matériel procurement, and project assignment to various engineer units. In order to relieve this division of some of the details three provisional engineer groups, designated as A, B, and C, were activated late in August with the sole mission of railway reconstruction. Each group included an experienced engineer general service regiment as a nucleus, plus additional regiments and other detachments. Two groups were immediately given the task of opening the railways behind the two armies; the third was initially placed in support of the other two and later assigned to support the Ninth Army. In this way close engineer support in railway reconstruction was provided for each army, while the Advance Section continued to exercise over-all direction of the reconstruction.17 At the end of August more than 18,000 men, including 5,000 prisoners of war, were engaged in rail reconstruction projects.18

Despite the addition of limited rail transport to Chartres and Dreux the rapid extension of the lines of communications in the first days of September continued to outdistance the transportation resources. It was not immediately possible to move large tonnages across the Seine by rail because of damage to the bridges and lines in that area. On the southern edge of Paris the bridge at Juvisy-sur-Orge, a vital link connecting the area west of Paris with the rail net to the east, was a major reconstruction project.19 Only two or three trains per day moved forward from Chartres at first, and only small tonnages could be forwarded eastward through the narrow bottleneck of Paris beginning on 4 September.20 As long as the extension of rail operations attempted to match the speed of the pursuit operating units had to forego many of the facilities normal to railroading and adopt makeshift arrangements, particularly in connection with signaling. Operations often resembled those of a third-class Toonerville Trolley more than model railroading. Under those conditions the ghost of Casey Jones shadowed many an engineer on the forward runs; as it did on 5 September at Maintenon, northeast of Chartres, where a blacked-out trainload of high-octane gas roared around a downgrade curve and crashed into another train, sending flaming Jerricans into the night.21

Beyond the Seine the entire railway picture was considerably brighter. For one thing, a much more extensive network existed to the northeast, including many of the main lines of the French system, and it had been kept in much better repair. More important, the railways in that area were not as badly damaged. Allied planes had not attacked them as persistently, particularly in recent months, as they had the lines in the OVERLORD lodgment area, and the enemy had had even less opportunity

to destroy them in the rapid retreat to the German border. East of Paris the railways therefore offered every prospect of being restored to operation quickly and of being able to handle a large volume of traffic.

In order to make the best possible use of this network while the through lines along the Seine were being restored, logistical planners decided to continue the movement of as much tonnage as possible by truck to the Seine and to transfer supplies to the railways, which could then carry them forward to the army areas. Transfer points were eventually established just outside Paris, where the cargoes of the Red Ball convoys were transferred to the railways for movement to the armies.22 At the railheads another transfer of supplies was necessary, this time to army transportation. While this entailed additional handling of supplies, it promised to effect great savings in the use of motor transport.

In the meantime ADSEC engineers had set about making the necessary repairs to the rail lines extending eastward. In the First Army area Engineer Group A quickly opened a line from Paris northeast through Soissons, Laon, Hirson, and via secondary lines to Charleroi and eventually to Namur and Liége. Farther south Group C opened a route to the Third Army from Juvisy to Sommesous, where a transfer point was established, and then on to Commercy and Toul.23 An additional line was then opened from Laon (on the northern line) via Reims eastward to Verdun and Conflans. Later in the month a better route was opened still farther north in support of the First Army, running north and northeast from Paris to Compiegne, St. Quentin, and via Cambrai to Mons and then to Namur and Liége.24 In all this work the Americans made extensive use of captured materials.

By mid-September upwards of 3,400 miles of track had been rehabilitated and more than forty bridges had been rebuilt. Nearly all of this work was accomplished after the breakout from St. Lô.25 By the end of the month rail lines had been opened eastward as far as Liége in the north and Verdun and Toul in the south, and bridge reconstruction was in progress at all three places. The rehabilitation of the railway had therefore proceeded far beyond what had been planned by that date.

This progress was reflected in the increasing tonnages forwarded by rail. As of 1 August cumulative rail shipments had totaled only one million ton-miles. A month later the total had risen to 12,500,- 000, and by mid-September shipments were averaging nearly 2,000,000 ton-miles per day. Beginning with the first driblet of supplies forwarded via rail east of Paris on 4 September, the daily tonnages handled beyond the Seine by the middle of the month averaged 5,000 tons and continued to rise.26

Though the railways thus assumed a greater and greater portion of line-of-communications hauling, the burden on motor transportation was not immediately relieved,

for requirements in the forward areas were also increasing. The demands of the armies consistently absorbed all available lift, and transportation resources were to fall short of needs for some time to come. In mid-September bottlenecks in the Paris area and shortages of rolling stock still constituted serious limiting factors, and the railways were only beginning to come into their own as the principal long-distance carriers.

Motor Transport

Because the transition from rail to truck was necessarily a gradual process, motor transport inevitably played a much larger role than originally anticipated. It was a role for which the motor transport facilities of the theater were neither well suited nor prepared. Logistical plans had been consistently based on the assumption that trucks would not be used for supply hauling at distances greater than 150 miles on the lines of communications.27 Nor had the Transportation Corps been able to obtain, even on this assumption, either enough vehicles of any kind, let alone the types which it had requested, or enough properly trained drivers.

Using troop basis and logistical planning factors of that period, the Transportation Corps had calculated in the summer of 1943 that the Communications Zone would require 240 truck companies to meet the needs for the three main types of hauling—port clearance, static interdepot operations, and long-distance line-of-communications transportation. Theater headquarters rejected this estimate and in November 1943, after attempting to cut the requirement to 100 companies, finally approved an allocation of only 160 companies, This requirement was then sub mitted to the War Department as a special procurement project (PROCO).28

The scaling down of its request was only the first of the handicaps under which Transportation Corps labored in its attempt to provide adequate motor transport for the continental operation. In two other important features the procurement plan fell considerably short of its target. The theater chief of transportation had originally directed that the vehicle procurement project be based on a proportion of two heavy-duty trucks to one light. The heavier transport, such as the 10-ton semitrailer and truck-tractor combination, was desired for long-distance hauling, while the lighter types, like the 2½-ton 6- x 6, were to be used for static inter-depot movements, for clearance of railheads, and on the poorer roads in the forward areas. In the project which the theater submitted to the War Department, using the 160-company basis, the two-to-one proportion was not adhered to. Almost all of the companies were to be specially equipped for specific missions, however, and the request included a sizable allotment of heavy-duty transport. Only 25 companies of standard 2½-ton 6 x 6 trucks were provided. The remainder were to be made up as follows: 36 companies were to have the long-bodied 2½-ton COE (cab over engine) trucks, best adapted to hauling light but bulky engineer equipment such as Bailey bridging and POL pipe; 27 companies

General Ross, Chief of Transportation, ETOUSA

were to have 750-gallon tank trucks; 9 companies were to have 2,000-gallon semitrailer tankers; 2 companies were to have 5-ton refrigerator vans (reefers); 2 companies were to have 45-ton tank transporters, which were suitable for port clearance of heavy out-of-gauge equipment in addition to the purpose for which they were designed; and 59 companies were to have the tractor-drawn 10-ton semi-trailer.29

The production and delivery of this equipment was another matter. As the winter of 1943–44 passed it became increasingly doubtful that even the scaled-down program would be met. The War Department approved the request for heavy-duty vehicles in December, but production difficulties in the United States thereafter proved the major hindrance to the fulfillment of the theater’s needs. At the end of March 1944 the theater had on hand only 66 of the 10-ton semitrailers against a requirement of 7,194. It had received none of the 4,167 4- to 5-ton truck-tractors required for towing. On this combination of semitrailer and truck-tractor General Ross, the theater chief of transportation, had depended to bear the principal burden of line-of-communications hauling.30

In April the theater G-4 decided to pool all PROCO projects and issue trucks on the basis of priorities, further dimming the Transportation Corps’ prospects. Since equipment such as the truck-tractor was an item common to several other services there was no guarantee that the Transportation Corps would get what it needed, regardless of the foresight it might have shown in the early submission of its program. TC project equipment was issued to other services, and also to the armies in the spring of 1944, with the inevitable result of limiting the movement capabilities of the Transportation Corps.31

As D Day drew nearer the delay in the shipment of vehicles made theater officials increasingly fearful that serious shortages in cargo-hauling capacity would develop, and the whole problem of motor transport became of major concern. Early in April

the chief of transportation submitted detailed data to the War Department supporting his claim that the theater would require all of the vehicles requested in order to carry out its missions.32 By that time it was obvious that the vehicles requested by the theater could not be made available. Late in April the War Department therefore took steps to meet the deficiency by ordering the release of a variety of substitute types of equipment from the Army Ground Forces, the Army Air Forces, and the Army Service Forces. Included were several hundred 1½-ton truck-tractors with 3- to 6-ton semitrailers, 4- to 5-ton truck-tractors with 25- and 40-foot 12½-ton wrecking-type semitrailers, and other miscellaneous types. In addition, the ASF was ordered to divert from production 1,750 4- to 5-ton truck-tractors and 3,500 5-ton semitrailers which had been intended for the Ledo Road project in Burma.33 By this last-minute roundup and diversion of transport Washington hoped to tide the theater over the critical period pending the arrival of the project equipment it had requested. Finally, where it was impossible to issue heavy-duty vehicles, units were equipped with the standard 2½-ton 6 x 6 truck. Theater transportation officers later were of the opinion that the War Department’s inability to deliver heavy-duty vehicles contributed materially to the bogging down of operations in the first days of September.34

Planning for the theater’s transportation requirements, like the planning for ammunition supply, was characterized by the absence of mutually acceptable planning factors and by disagreement between the various headquarters concerned as late as a month before D Day. Elaborate precautions had been taken to insure coordination of all planning and adequate liaison between the various staffs, but General Ross was not even represented at 21 Army Group headquarters and found that reliance on the theater general staff for planning data was not satisfactory.35 The theater chief of transportation and the Forward Echelon, Communications Zone, had repeatedly asserted that the planned allocation of motor transport would be inadequate unless the planned build-up of reserves was scaled down, the build-up was reduced, or a larger portion of both reserves and troop units was held in the rear areas. The Forward Echelon had recommended an increase in the motor transport allocation of about a hundred companies.36 The ETOUSA G-3 had disallowed these requests.

Meanwhile, the SHAEF G-4 instituted his own studies of transportation needs, branding the theater staff’s computations as “unreliable” and “worthless.” According to the SHAEF planners, the theater had based its studies on much higher tonnage requirements than they considered

necessary.37 Estimates of transport capabilities naturally varied depending on the assumptions as to port capacities, the distribution of reserves, the type of motor transport available, and other factors.

By mid-May, after a recalculation of transportation requirements, the area of disagreement had narrowed somewhat. General Crawford reported to the War Department at that time that all headquarters were satisfied that the minimum motor transport requirements up to about D plus 50 could “just be met” if truck companies and vehicles became available as then scheduled.38 Some staff officers were less sanguine, predicting a shortage as early as D plus 30. They believed that the deficit could be eliminated only if the railways assumed a portion of the movement burden at an early date.39 Beyond D plus 50 the theater’s position was even more unpredictable because of the uncertainty over the receipts of heavy equipment.

The lag in delivery of motor transport equipment had a direct bearing on another important aspect of TC preparations—the training of drivers. As it did in the case of other types of service units, the theater agreed to accept partially trained truck units with the hope of completing their training in the United Kingdom. The lack of vehicles—particularly the special heavy-duty equipment—made this all but impossible. The small depot stocks which existed in the theater were earmarked as T/E equipment for high-priority units. In the fall of 1943 the Transportation Corps requested that at least a few of these vehicles (one or two semitrailers and truck-tractors for each company scheduled to operate them) be issued for training purposes. The proposal was not approved until May 1944, and only superficial training could be given in the short time that remained. Its inadequacy was eventually revealed by the damage which the heavy equipment suffered at the hands of inexperienced drivers.40

In still another vital aspect—adequate numbers of drivers—plans for a satisfactory motor transport system were at least partially voided by failure to take timely action on the chief of transportation’s recommendations. British experience in North Africa had long since demonstrated the value of having enough extra drivers to permit continuous operation of vehicles. With this knowledge theater TC officials had requested as early as August 1943 that an additional thirty-six drivers be authorized for each truck company so as to provide two drivers per vehicle (ninety-six per company) and thus make it possible to carry on round-the-clock operations. The ETOUSA G-3 initially disapproved the idea, insisting that it was unnecessary.

To the Transportation Corps the necessity to plan for twenty-four-hour operations was clear from the beginning, and the need for extra drivers became even

more urgent as the prospect of obtaining the original allocation of truck companies began to wane. It therefore persisted and at the end of the year succeeded in getting another hearing, this time buttressing its earlier arguments with additional experiential data from the Mediterranean theater. Early in 1944 General Lee personally interceded in support of the TC proposal, and approval was finally obtained from the theater to request the additional personnel. By that time the War Department had established a ceiling for the theater troop basis and refused to furnish additional men without making corresponding reductions elsewhere. Left with no other choice, the theater therefore took steps to make the necessary personnel available from its own manpower resources. In mid-April General Lee was ordered to transfer 5,600 men from units in the SOS in order to provide an additional 40 drivers for each of 140 companies. In ordering the release of the men General Lee warned chiefs of services and installations commanders that he would not countenance any unloading of undesirables. Despite this familiar injunction the truck companies were saddled with many individuals who could not be trained as drivers. The search for men, furthermore, fell short of the goal, and was too belated to permit adequate training before the units were called to perform their mission on the Continent.41

To compensate for these inadequacies the Transportation Corps resorted to still other expedients. Shortly before D Day most of the men in fourteen existing colored truck companies were transferred to other colored motor transport units, the intention being to fill the stripped units with other white troops. This did not prove immediately possible, however, and the fourteen companies remained inoperative as late as mid-August. Meanwhile, the loss of the fourteen units was temporarily compensated for by the transfer of their vehicles to two engineer general service regiments,42 which were converted into trucking units. By an involved administrative sleight of hand, the results of which were not entirely satisfactory, the deactivation of these units was therefore avoided, and the two organizations retained their designation as engineer regiments, although they were used as truck units by the engineer special brigades at the Normandy beaches.43 By such expedients some of the most urgent requirements were met, but the failure to furnish adequately trained men had its inevitable effect later, particularly in poor vehicle maintenance. Thus, still another of the Transportation Corps’ farsighted proposals was largely negated.

The delay in implementing the Transportation Corps’ recommendations on motor transport fortunately did not affect supply support in the first two months of operations. Despite the fact that only 94 of the scheduled 130 truck companies had

been brought to the Continent at the end of July, the available motor transport proved entirely ample for the short-distance hauling requirements in the period during which U.S. forces were confined to the Normandy lodgment.44

The breakout at the end of July quickly eliminated any existing cushion. The sudden success of early August brought heavy demands on all the available transport, for the amount of transportation in effect shrank with every extension of the lines of communications because of the longer turn-round required between the rear depots and forward dumps. Outstanding among the immediate tasks were movements of gasoline to the Third Army. On 11 August the daily POL hauling requirement for Advance Section was raised from 300,000 to 600,000 gallons. On 5 August 72,000 tons of ammunition were ordered to a dump forty miles inland from OMAHA Beach. A few days later a 10-ton flat-bed company was assigned a four-day haul of POL pipeline material. By mid-August hauling missions were more and more exclusively devoted to the movement of the barest essentials.45

In the second week of August the first steps were taken to meet the growing demands by augmenting the lift capacity of the Advance Section’s Motor Transport Brigade. On 10 August two companies of 45-ton tank transporters were converted to cargo carriers. A few days later ten additional trucks were distributed to each of fifty-five companies equipped with the 2½-ton 6 x 6, and 1,400 replacements were obtained for temporary duty to handle the additional equipment.46

During August the Advance Section also had the use of three British companies. Between 300 and 360 trucks, of 3-, 6-, and 10-ton capacity, were loaned by the 21 Army Group for a full month, and were used mainly to carry supplies from railheads forward to Third Army depots.47 In the armies, meanwhile, replacements were also used as relief drivers in order to make fuller use of available vehicles.48

By taking such measures and by increasing the use of army transport facilities for long-distance hauling, it was possible to support the forward elements at fairly adequate scales for the first three weeks of August. The decision to cross the Seine and press the advance eastward at this time, however, constituted an important departure from the OVERLORD plan and presented the Communications Zone with a much more serious logistic problem. To support the armies beyond the Seine the Communications Zone announced as its initial target the placing of 100,000 tons of supplies (exclusive of bulk POL) in the Chartres–La Loupe–Dreux triangle by 1 September. It assumed at first that approximately one fifth of this tonnage could be delivered by rail, leaving 82,000 tons to be moved by truck.49 The planners immediately realized that meeting this demand

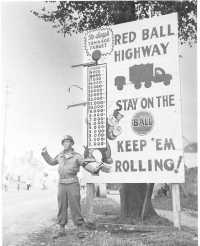

required a more effective marshaling of transportation resources. Out of this necessity the famed Red Ball Express was born.

Taking its name from railway parlance, the Red Ball Express was planned as a fast “through freight” which would have exclusive use of a one-way loop highway, operating round the clock and utilizing all available motor transport. Unfortunately there was little in the way of either plan or precedent which could be used in organizing the system. The Transportation Corps had given some thought to the problem during the planning period in the United Kingdom and had wanted to make a test run of continuous long-distance hauling for purposes of experimentation and training. It had planned to operate truck-tractor-semitrailer combinations over a 300-mile stretch continuously for several weeks with assumed stops for loading and unloading, regular halts for rests, meals, and maintenance, and alternating drivers. Such a trial run undoubtedly would have produced valuable data on such matters as maintenance, driver fatigue, requirements for various types of equipment and for drivers, and therefore would have aided materially in the preparation of SOP’s for operations of this type. But neither the equipment nor the manpower was available in time for such a test.50 The only training exercise which even faintly resembled the conditions of the later express system was a test run conducted to determine the efficiency of another Red Ball system—the shipping procedure devised to handle emergency shipments of supplies from the U.K. depots to the far shore. This procedure involved both rail and motor movements from the depots to the U.K. ports as well as cross-Channel shipping. Trucking units carried out a test run of this procedure on the night of 3–4 June, but the trial was of very limited duration, and while it revealed many defects it hardly served as a test of the type of continuous and large-scale motor transport operations which were now attempted.51

The urgency of the mission allowed little time for deliberation or planning, and the Red Ball Express therefore was largely an impromptu affair. Not until 23 August was the Advance Section questioned concerning its ability to make the desired deliveries.52 Two days later the convoys began to roll eastward. The Red Ball plan was worked out jointly by officers of Headquarters, Communications Zone, and the Advance Section, two of the officers most instrumental in its implementation being Lt. Col. Loren A. Ayers, chief of the Motor Transport Service, Headquarters, Communications Zone (later deputy commander of the Motor Transport Brigade), and Maj. Gordon K. Gravelle, also of COMZ headquarters. The plan called for the pooling of almost all of the Communications Zone’s motor transport facilities in one organization—the Advance Section’s Motor Transport Brigade (MTB), then commanded by Col. Clarence W. Richmond. It was agreed that the Advance Section should be given 141 truck companies with the understanding

that all would be placed on line-of-communications hauling with the exception of five companies reserved for railhead distribution in the Le Mans–Chartres area.53 Initially 118 companies were designated for Red Ball use.

More than seventy companies were already operating under the Advance Section, which on the first day was able to place sixty-seven companies in operation and deliver 4,482 tons of supplies to the Dreux–Chartres area. An additional forty-one companies were immediately allocated to Red Ball from the motor transport of the recently activated Normandy Base Section. The speed with which the system was organized is indicated by the fact that the Red Ball reached its peak performance within the first five days of operation. On 29 August 132 companies with a strength of 5,958 vehicles were committed and on that day 12,342 tons of supplies were delivered forward, a record which was not again equaled in the succeeding eleven weeks during which the express service continued to operate. Some of the initial confusion attending the organization of the express route is indicated by the fact that traffic control personnel were sent to Verneuil, west of Dreux, only to find after three days of waiting that the route had meanwhile been altered.54

Red Ball fell slightly short of its objective of 82, 000 tons to be delivered by 1 September. The time was then extended several days, and the tonnage target was also increased because of the inability of the railways to move the tonnage originally assigned them. By 5 September, the date at which the Red Ball’s original mission was considered completed, approximately 89,000 tons of supplies had been delivered to the Dreux–Chartres service area via motor transport.55 On that date

Col. Ross B. Warren replaced Colonel Richmond as commander of the Motor Transport Brigade. Deliveries in the first days had averaged approximately 7,400 tons. In addition, however, trucks of the Motor Transport Brigade hauled about 48,000 tons forward from railheads at Le Mans, Chartres, and Dreux.56

In this initial phase the Red Ball route consisted of two parallel highways between St. Lo and Chartres, one for outbound traffic and one for the return. (Map 18) Red Ball trucks actually traveled northward to the base depot in the vicinity of the beaches and even to Cherbourg to pick up their cargo, but St. Lô was the control point from which the convoys were dispatched forward. The entire express highway route was marked with the characteristic red ball marker which pointed the way for drivers. Because of the density of traffic, and in order to assure the most efficient control of traffic, specific rules were laid down to govern the operation of Red Ball trucks. Use of the highway, for example, was reserved exclusively for Red Ball vehicles; all traffic was to move in one direction; all trucks were to be organized into convoys which in turn were divided into serials; the maximum allowed speed was to be twenty-five miles per hour; convoys were not to halt except for the specific ten-minute “break” at exactly ten minutes before each even hour; a sixty-yard interval was to be maintained between all vehicles and there was to be no passing; stragglers were to fall in at the end of convoys hauling similar commodities and eventually rejoin their own

Directing traffic along the Red Ball Route. Sign shows tonnage target for the day, 5 September 1944

Map 18: Routes of the Red Ball Express

units upon return; disabled vehicles were to pull to the side of the road until evacuated or repaired by ordnance patrols.57

Such regulations were obviously needed if the stream of traffic was to be kept flowing smoothly and without congestion. Operations were to continue twenty-four hours per day, and in order to allow the best possible speed at night Red Ball convoys were freed from the usual restrictions regarding the use of “cat eyes” and were permitted to employ full headlights, initially as far east as Alençon and later throughout the Communications Zone. This relaxation of normal blackout regulations was made possible by the almost

total absence of the German Air Force west of the Seine. Bivouac areas for the truck companies assigned to the Red Ball Express were located south of Alençon, approximately midway along the express system and astride the outgoing and returning routes, thus permitting a change of drivers at the halfway mark on each run.58

Operating the Red Ball Express proved a tremendously complex affair entailing much more than simply driving trucks, for it required a multitude of ancillary services provided by services other than the Transportation Corps. In addition to actually operating the convoy the Transportation

Corps, in co-ordination with military police units, regulated the movement of traffic. Traffic control points were initially established in all the main towns to record the movement of convoys, check their destination and cargo, and inform convoy commanders on the location of refueling and water points and of ordnance maintenance units. Military police units aided in this control by regulating traffic at intersections and defiles, enforcing the restriction on the use of the Red Ball route, directing casual vehicles and stragglers, checking improper use of lights, and in general policing and patrolling the routes. Maintenance of the routes was a responsibility of the Corps of Engineers, which designated two general service regiments for the task and assigned specific sections of the highway to platoons bivouacked along the routes.59 Engineers also made several thousand road markers and additional signs in both French and English warning unauthorized vehicles to stay off the Red Ball routes. Ordnance units—mainly automotive maintenance companies—were initially stationed at eight of the principal towns along the route to afford repair facilities and provide replacement vehicles. In addition, ordnance maintenance shops sent patrols and wreckers out along the route. Signal Corps units provided radio communications between bivouac areas and diversion points, and a courier service was established between regulating stations and the forward dumps. Finally, the Medical Corps established an aid station in the bivouac area and provided ambulance service for the evacuation of casualties to near-by hospitals.60

The Red Ball plan was thus a well-conceived one. Unfortunately the actual operation of the express service, particularly in its early stages, left much to be desired. Many of its difficulties centered around the problem of traffic control. From the beginning Red Ball suffered a chronic shortage of MP’s to police the route, with the result that it was next to impossible to reserve routes for the exclusive use of Red Ball trucks and supporting vehicles. First Army, Third Army, and the Ninth Air Force all ran convoys over the routes without clearing with the Advance Section, and other vehicles, both military and civilian, attempted to move against the stream of traffic.61 Red Ball drivers regularly disregarded convoy discipline and the twenty-five-mile-per-hour speed restriction. The latter was a common violation of convoys attempting to make up lost time, and of stragglers determined to catch up with their convoys.62 Among British units gossip had it that to avoid a U.S. convoy one must “not only get off the road but climb a tree.”63

Meanwhile vehicles were often used uneconomically, both through loading to less than capacity and through delay and loss of time in loading and unloading. Only a few days after Red Ball began operations Colonel Ayers, following a study of the first tonnage reports, asked the COMZ G-4 to set minimum tonnages for each type of vehicle, in some cases 50 to 100 percent above rated capacity.64 In the early stages the loss of time resulted in

part from the scattered location of dumps at both ends. Even in late September an analysis in Normandy Base Section revealed that the fastest loading time for a convoy was 11.5 hours, while in a few cases 34 to 39 hours were required. Unloading in the forward areas was equally unsatisfactory. There were other factors which contributed to the delays in the base areas. Trucks were often sent to depots in advance of the time loading could begin, sometimes arriving before the depot received the order to ship. In other cases the number of trucks sent to the depots was inadequate to take loads with high bulk ratios. This difficulty was eventually remedied by requiring the chiefs of services to furnish cubage as well as tonnage estimates on requisitions so that traffic control regulating points could allot the proper number of vehicles.65

Maintenance of motor transport equipment also fell far short of the ideal. In mid-September it was discovered that no ordnance service was available on the return route between Chartres and St. Lô, and that twenty-seven companies of one truck group had been without maintenance between 10 and 12 September. In one survey eighty-one loaded vehicles were found unserviceable along the highway between Vire and Dreux.66 The lack of such service was particularly noticeable after the Red Ball route was extended on 10 September.

Another difficulty that plagued Red Ball operations was the “losing” of convoys through diversion to points other than ordered. The Communications Zone had complained as early as the first week in August about the armies’ practice of asking ADSEC drivers to deliver supplies to division supply points, admittedly an abnormal procedure. COMZ officials insisted that ADSEC drivers were not prepared to deliver supplies that far forward, that they were unfamiliar with routes in the forward areas, and that such a practice slowed the turn-round of trucks, entailed a loss of time, and generally limited the Communications Zone’s ability to meet the armies’ requirements.67 But that problem was soon put in the shade by the necessity to travel greater and greater distances to put down supplies even as far forward as the army maintenance areas. Convoy movement instructions were issued at the base depots in Normandy Base Section, which designated the regulating station through which cargoes were to be routed. The regulating station in turn designated the dumps at which convoys were to unload their supplies and notified the dumps of the approach of the convoy.68 This planned co-ordination and synchronization often broke down in practice. Regulating stations frequently did not get advance information from the bivouac area of the approach of convoys, and the dumps consequently often received notice of the approach of a convoy only a few minutes before its arrival instead of the six or seven hours intended. The Communications Zone attempted to correct this deficiency by directing the agencies dispatching convoys to inform regulating stations twice daily by TWX of the number of convoys and class of supply dispatched.

Such measures met only part of the difficulty. Convoy commanders found within only a week of the establishment of the express

that they had to travel farther and farther to reach the army dumps, and in some cases could not even find them. Despite the fact that Chartres had been designated as the terminus of the Red Ball, convoys were regularly diverted from the dumps west of the Seine to new ones farther east, with the result that within the first ten days of the operation the turn-round time was increased by 30 percent. Convoys often traveled an additional 50, 60, or even 100 miles before locating an appropriate dump, and after the Red Ball route had been extended to Hirson and Sommesous, in support of the First and Third Armies respectively, they sometimes went as far as Maastricht, Verdun, and even Metz, far beyond the official termini of the Red Ball routes.69 At times army dumps actually closed while convoys were en route from the regulating station. Commodity-loaded convoys, which were ordered to dumps of a particular class of supply, were often forced to “peddle” their loads until their cargoes were finally accepted.70

In the initial stages of the operation the control of Red Ball vehicles was extremely loose. The original injunction that convoys move in company strength was immediately violated, and was then relaxed to permit convoys of platoon strength.71 But detachments of a few vehicles were frequently sent to the base depots to pick up small consignments and then dispatched forward. Early in September Normandy Base Section noted that less than one third of all trucks were moving in organized convoys, and in the middle of the month the Communications Zone again forbade this practice. It directed that where the dispatch of a full company to the loading points was not warranted trucks were to be marshaled into convoys as complete company units before being cleared for the run forward of St. Lô.72

Part of the early confusion undoubtedly arose from the haste with which the Red Ball enterprise had been organized and the lack of experience in conducting such an operation. The fluid conditions in the army areas also contributed to the difficulties, for the constantly shifting maintenance area resulted in longer and longer turn-rounds, increased the difficulties of control, stretched the meager resources of the maintenance service, and upset all schedules of delivery.

In addition, the operation was conducted under what the Transportation Corps regarded as an unsatisfactory control arrangement for motor transport. The organization of motor transport on the Continent presented no great problem as long as the command and organizational structure remained fairly simple. Until early August all hauling was carried out by the truck units of either First Army or the Advance Section, and centralized direction was achieved by virtue of First Army’s command of the entire lodgment area. Anticipating the time when it would have a role independent of the armies the Advance Section, barely a month before

D Day, had organized its truck units into the provisional Motor Transport Brigade in the firm conviction that centralized control of motor transport was desirable. In the early phases the MTB did not actually control truck units assigned to the

beach brigades or those assigned to port clearance at Cherbourg. After the drawing of the army rear boundary, centralized control of motor transport in the base area was in effect for only a short period early in August during which the Advance Section was the sole base section on the Continent.73

When the Red Ball Express was organized later in the month, centralization was achieved to the extent that the MTB, operating under the command of the Advance Section, was assigned responsibility for carrying out the mission and given the use of the bulk of the motor transport resources in the Communications Zone. The brigade’s control of movements was not actually complete, however, for a second COMZ section—Normandy Base Section—had been activated in the meantime, and the brigade theoretically did not have control beyond the Advance Section’s boundaries. This limitation was not serious at first, for the Advance Section initially controlled the entire area between St. Lô and the army rear boundaries. Normandy Base Section controlled the area north of St. Lô and was responsible for loading convoys and issuing movement instructions. But the control of motor transport operations became considerably more complex as commands were further multiplied, as the Red Ball route was extended, and as ADSEC responsibility was shifted farther eastward.

The Red Ball completed its original mission on 5 September, but necessity dictated that its life be extended, and the following day it entered its second and lengthier phase of operations. Five days later the Red Ball route was altered somewhat and extended eastward through Versailles, where it diverged into two routes, one extending northeast to Soissons (in support of the First Army) and returning via Fontainebleau, Etampes, and Alençon, and the other branching off from Versailles eastward to Rozay-en-Brie and Sommesous (in support of the Third Army) and also returning via Fontainebleau. On 20 September the northern route was extended still farther to Hirson, and there were other minor alterations in the routes followed.74

In the course of these changes additional base sections were also created and given area command. By early October Red Ball convoys were required to pass through as many as five sections, with all the delays entailed in the co-ordination of changes in route, supply, and traffic control. Even though the Motor Transport Brigade, an ADSEC organization, continued to operate the express system, many aspects of the enterprise, such as the provision of road and vehicle maintenance, policing, signal communications, and other services, were divided among the various base sections. The proper co-ordination of all these activities created an impossible administrative burden. The new sections did not always immediately assume responsibility for all these functions. In some cases they lacked military police or signal or engineer troops; often the new sections were not informed of the most recent operational instructions. Attempts were made to eliminate these difficulties by issuing clearer instructions to base sections, but the confusion and misunderstandings about the extent of control and responsibility of one base section vis-à-vis an adjacent one did not immediately clear up. Contrary to the

theory on which the base section system had been established, the Advance Section meanwhile attempted to exercise over-all supervision of movements along the entire Red Ball route and only incurred the criticism of other commands for its pains. Late in September the Seine Section (comprising the Paris area) complained that ADSEC representatives were making unauthorized diversions and changing consignments at truck-to-rail transfer points which were within Seine Section territory. Not until December, after the Red Ball had come to an end, was a system of uniform traffic regulations adopted.75

The difficulties inherent in decentralized control of an intersectional activity such as motor transportation illustrated an age-old problem—the conflict between the functional and regional division of responsibility. The Transportation Corps had fully recognized that jurisdictional problems would inevitably arise in a system of regional control and repeatedly advocated centralized control of operations which traversed sectional boundaries. But its recommendations had not been approved.

By the end of the pursuit in the middle of September Red Ball had delivered a total of 135,000 tons to the army service areas.76 The number of truck companies available to the MTB for the Red Ball runs fluctuated considerably, and the average was far below the peak strength of 132 attained within the first few days. In the first weeks of September approximately 115 truck companies were used, although the MTB sometimes had upwards of 130 companies assigned and the Communications Zone as a whole had 185 companies on the Continent.77

To muster this amount of transportation the Communications Zone had to resort to many expedients, among them the elimination of all unessential hauling and the temporary creation of provisional truck companies out of a variety of both service and combat organizations. At the very start forty companies were transferred from the Normandy Base Section to the MTB, and both base sections had to exercise the most stringent economy. The Communications Zone immediately called for surveys of all organic cargo-carrying vehicles of every unit assigned or attached to static or semi-static units and ordered that all vehicles, with drivers, that could be spared for four or more hours per day be made available on a temporary basis to base section transportation officers for inter-depot hauling and for port and beach clearance.78 In a further effort to meet requirements for line-of-communications hauling the Communications Zone reduced the activities at the beaches and ports by 50 percent and forbade the shipment of any supplies from the U.K. depots for which there was not an urgent need.79

To augment the available transportation, provisional truck companies were

Tractor-Trailer Combinations used on the Continent

4–5-ton, 4 x 4, truck tractor, COE, with 2,000-gallon gasoline semitrailer

1½-ton, 4 x 4, truck tractor with 3½-ton stake and platform semitrailer

12-ton, 6 x 4, truck with 45-ton trailer (tank transporter)

organized in the meantime from both service and combat units. In Normandy Base Section two engineer general service regiments were reorganized into seven truck companies each, and a chemical smoke generating battalion was reorganized as a truck battalion, its four companies being equipped with standard 2½- ton 6 x 6 trucks.80 An additional ten companies were organized from antiaircraft units. Finally, three infantry divisions recently arrived on the Continent—the 26th, 95th, and 104th—were immobilized and their vehicles were used to form provisional truck companies. More than forty companies were organized in these divisions with the aid of 1,500 vehicles which the Communications Zone drew from stocks intended for issue to other units.81

The Red Ball Express by no means accounted for all the hauling during the period of the pursuit, nor even for all the long-distance hauling. A considerable amount of transport was used in clearing ports, and the MTB devoted a sizable portion of its transport to hauling forward of the railheads.82 The armies also accounted for a substantial portion of long-distance hauling, although the extent and volume of it are not recorded. Like the Communications Zone, the armies took special measures to marshal all transportation resources and pressed every cargo-hauling vehicle into service. Both First and Third Armies made progressively greater use of both combat and service units that could be spared for cargo hauling. On 22 August General Bradley instructed both armies to leave their heavy artillery west of the Seine and to use the freed cargo trucks for supply movement, and the Communications Zone was asked not to move heavy-caliber ammunition beyond the Seine.83 Thereafter extensive use was made of all types of units. By the end of August the First Army was using engineer tactical transportation—three heavy ponton battalions, two light ponton battalions, and two dump truck companies—for supply movement.84 Within another two weeks it was using a total of eighteen battalions of its artillery, with approximately 450 trucks of the 2½-ton type or larger and more than 200 lighter vehicles (¾-ton). By the end of September these converted field artillery battalions alone had hauled 17,200 tons of supplies.85 Meanwhile 340 trucks were taken from antiaircraft artillery units to form provisional truck companies, and units of other services also assigned their organic transport to hauling army supplies. In this way vehicles were drawn from evacuation hospitals, gas treatment battalions, mobile refrigerator companies, salvage and repair companies, engineer camouflage units, signal depot and repair companies, ordnance maintenance companies, and other types of units.86 Third Army resorted to similar expedients.

There is no doubt that but for these special measures in marshaling the transportation resources in both the communications and combat zones the advance of the armies could not have been sustained as far as it was. Throughout the period of the pursuit motor transport, contrary to all expectations, bore the preponderant

burden of supply movement over distances up to 400 miles. By far the most lavishly publicized for this feat was the Red Ball Express. The campaign by which praise was heaped on the Red Ball driver in such public organs as The Stars and Stripes and Yank and in commendation from Headquarters, Communications Zone, undoubtedly served a useful purpose, dramatizing the urgency of moving supplies forward and enhancing the morale of men performing a duty which was monotonous, devoid of glamor, and normally unpublicized. Although his later performance in the XYZ operation, the express service organized to support the final drive into Germany in the spring of 1945, far surpassed that of September 1944, it was for the latter that the Red Ball driver was to be remembered and even memorialized in song in a Broadway musical show entitled “Call Me Mister.”87

But Red Ball was carried out at a terrible cost. As early as mid-September the mounting strain on both personnel and equipment was already clearly evident. The almost continuous use of vehicles without proper maintenance could have only one result—rapid deterioration of equipment. Just such a deterioration was reflected in the rise in major repairs, from 2,500 in mid-September to 5,750 by the end of the month.88 Contributing to this increasingly dangerous maintenance problem was the constant abuse of vehicles. Drivers habitually raced their trucks at double the established twenty-five-mile per hour speed limit, and overloading by 100 percent was an accepted practice as a result of authorization granted before D Day by the War Department.89 But the conditions under which overloading had been tested and approved by the Ordnance Department over improved roads at Aberdeen, Maryland, were not always duplicated on the grueling runs in northern France. In tires alone the replacement figure for the 8-ply 750 x 20 tire, the type most commonly used, rose from an average of 29,142 in preceding months to 55,059 in September, and in mid-September 40,000 of that type awaited repair.90 Theater stocks of tires were rapidly nearing exhaustion, as were spare parts and tools. Repair facilities simply were not equal to the task suddenly thrown upon them.

A similar strain was felt by personnel. Extreme fatigue not only resulted in accidents but also led to sabotage and malingering. In some instances drivers tampered with motor mechanisms with the express purpose of incapacitating their vehicles and falling out of a column.91 The Red Ball Express had even more sordid aspects. In the absence of enough MP’s for traffic and convoy control, the least scrupulous drivers sold their cargo on the French black market.92

Red Ball bore many of the defects of an operation hastily organized under the pressure of events to meet an emergency: there had been insufficient time for planning; extensive use had to be made of hastily organized provisional units, with all the disadvantages inherent in such practice; and there was a costly attrition

of equipment due to the necessity of temporarily suspending many of the normal precautions of maintenance. Red Ball was part of a gamble, part and parcel of the tactical decision to cross the Seine and exploit to the full the existing tactical advantage. That gamble had prospects of great rewards, and in the light of the optimistic tactical outlook at the time the all-out logistic effort was undoubtedly justified despite its great cost. But the result was debilitating to the logistic structure, and the effects were to be felt for several months to come.

Supply by Air

To alleviate the desperate shortage of transport in the period of the pursuit it was natural that air transport, like other movement facilities, should be exploited as fully as possible. Supply by air was no magic solution, however. The advantages it had of speed and freedom of movement were offset by many limitations, including low volume and tonnage capacity, uncertain availability of suitable aircraft, inadequate ground facilities at both loading points and landing fields, enemy interference, and hazardous weather. In recognition of the costliness involved in using troop carrier and transport aircraft for routine large-scale supply, field service regulations specified that supply of ground units by air was intended only as an emergency expedient. The normal mission for air transport as a medium of supply for other than airborne units included only the resupply of units which had been cut off from normal channels of supply by terrain, distance, or enemy activity.93

Subject to these restrictions the OVERLORD administrative plans had definitely contemplated the use of aircraft for both supply and evacuation. At the end of April 1944 Supreme Headquarters set forth the conditions and procedures for supply by air. It specified two types of supply—scheduled and emergency. The former was defined as supply by air provided to meet predetermined commitments normally anticipated and planned for in advance of an operation, such as the resupply of an airborne unit for a short period following a drop. Emergency supply was defined as that provided to meet demands resulting from unforeseen situations requiring urgent movement of either supplies or personnel.94

SHAEF also outlined the entire procedure by which bids for air supply were to be submitted and aircraft were to be allocated, and directed the Allied Expeditionary Air Force to establish an agency to control all air transport which might be allocated for supply and evacuation. In accordance with this directive the air commander in chief directed that the Combined Air Transport Operations Room (short title, CATOR) be established at Stanmore, England, as a special staff section of Headquarters, AEAF.

In effect CATOR was to serve as a regulating station for the control of all air traffic involving the use of Allied troop carrier and transport aircraft on supply missions other than those for airborne forces. The employment of all craft for such purposes was actually subject to the control of the Supreme Commander, who determined the allocation of craft in all cases of conflict between demands for emergency air supply and for airborne

operations.95 Subsequently both ETOUSA and 1st Army Group also issued instructions to their respective commands outlining the procedure to be followed in requesting air movement of supplies.

The use of air transport in June and July barely indicated the extent to which it was later to be developed, although the movement of both supplies and personnel by air filled an important gap in the meeting of emergency needs even in the first two months. The first supply by air in the OVERLORD operation consisted of prescheduled movements to the airborne units in the Cotentin and immediately revealed some of the difficulties inherent in the use of air for that purpose. Of 208 craft dispatched to the 82nd Airborne Division on D plus 1, 64 were forced to return to base with their loads by the sudden development of bad weather en route. Of the 250 tons dispatched, 155 were dropped, of which 90 percent was recovered by the ground units.

Supplies for the 101st Airborne Division were set up on an “on call” basis, but a misreading of ground panels by reconnaissance aircraft led to the dispatch of 118 planeloads of cargo which, it later developed, had not been requested and which the division was not prepared to receive. How large a portion of these supplies was recovered is unknown. Other aircraft flew successful on-call missions to the 82d Airborne Division in the first week, however, delivering supplies by either parachute or glider, the gliders carrying mainly 105-mm. howitzers and heavy machine guns.96

Twice in June supplies were flown to units other than airborne forces. On 8 June fifteen pounds of ether were dropped to a field hospital in the vicinity of Carentan, and two weeks later, during the period of the storm, food and water were dropped to an antiaircraft artillery unit isolated on the Iles St. Marcouf off UTAH Beach. Emergency deliveries by parachute were again necessary early in August when an infantry battalion was cut off by the enemy counterattack at Mortain. Lack of marking panels and prearranged drop procedure made it extremely difficult to locate the battalion accurately. On 10 August twelve aircraft successfully dropped loads of food, ammunition, and medical supplies on a hilltop east of Mortain, but of twenty-five craft dispatched on the following day less than half made successful deliveries, the remainder dropping their cargo a mile and a half short of the area as the result of poor visibility.97

In the meantime aviation engineers opened emergency landing strips in the beachhead area, the first of them within the first week of the invasion, making it possible to air-land supplies and personnel on a larger scale. Small shipments of supplies began in the third week of June. Air transport was used most heavily during the period of the storm, a total of approximately 1,400 tons of supplies, mostly ammunition, being shipped in the week of 18–24 June. By the end of July the IX Troop Carrier Command had flown approximately 7,000 tons of supply to U.S. forces on the Continent.98 Meanwhile air transport was increasingly employed for the evacuation of casualties. By the end of July about 20,000 troops, approximately one fifth of all U.S. casualties, had been

evacuated to the United Kingdom via air.99

Although the cumulative tonnage transported to the Continent in the first two months was not large, air transport had definitely proved its worth. First Army, having tasted its advantages, was anxious to establish air service on a scheduled basis. In fact, there was suspicion in July that the army was already making unauthorized use of air transport, for the First Army supply services in mid-July began to call regularly for delivery of over 400 tons per day by that means. By informal agreement with the Ninth Air Force these demands were reduced to a maximum of 250 tons. But CATOR began to question the “emergency” nature of the army’s requests, and both the U.S. administrative staff at 21 Army Group and SHAEF shortly thereafter issued reminders that air shipments were to be called for only when supplies were urgently needed and no other means of transportation was available. They gave instructions that all items not in the emergency category be stricken from supply-by-air demands (known as SAD’s).100

As this attempt was made to keep the use of air transport within prescribed bounds, steps were taken to develop the theater’s airfreight capacity to its full potential. In mid-June Supreme Headquarters directed the AEAF to prepare and submit plans for supply by air at the rate of 1,500 tons per day by D plus 30–35, and 3,000 tons per day by D plus 45. The main problem involved in developing such capacity lay in the provision of landing fields on the Continent, and within a few days the AEAF responded with a plan outlining the requirements for fields and the supplies and units needed to build them. SHAEF approved the plan and on 11 July directed the 21 Army Group commander and the Commander-in-Chief, AEAF, to provide the airfields and other facilities as early as possible.101 By mid-July, then, plans had been initiated to provide landing facilities on the Continent capable of receiving a total of 3,000 tons per day, half in the British sector and half in the American.102

This goal had not yet been reached at the end of the month, but the Allies intended shortly to test the expanded organization to the extent of a 500-ton lift to each sector.103 The desirability of developing the largest possible airlift potential became even more apparent within the next few weeks. Only a few days after the breakout at Avranches logistic planners at SHAEF began to study the possibility of supporting a rapid advance to the Seine. Included in their calculations was a consideration

of the extent to which such a drive might be supplied by air. At that time there were plenty of aircraft that could be utilized to deliver the 3,000 tons per day to the Continent, the only question being whether they should be used in planned airborne operations.

Far more serious a limiting factor was the inadequacy of reception facilities on the Continent. To make full use of the available airlift six strips, each with an estimated capacity of 500 tons per day, would have to be either captured or constructed. At the beginning of August the Allies had only one administrative field on the Continent, at Colleville, near OMAHA Beach, and the airlift organization had thus far been tested only to the extent of delivering about 500 tons per day to the U.S. sector.104

There was little doubt that air supply would add substantially to Allied offensive capabilities. It was estimated that the delivery by air of 1,000 tons per day would expedite by several days the accumulation of reserves necessary for crossing the Seine and would increase by two divisions the force that could be supported in an offensive across that river. On 12 August SHAEF announced to the major subordinate commands its intention of making air transport available up to 1,000 tons per day to the forward areas should the army groups desire such support. It indicated that aircraft would be withdrawn temporarily for contemplated airborne operations, but could thereafter be released in larger quantity for the support of U.S. forces beyond the Seine.105 The 21 Army Group accepted the offer with alacrity, replying on 14 August that it desired, subject to a small lift for British account, more than 2,000 tons per day for support of U.S. forces, initially in the Le Mans area and later shifting to the region of Chartres–Dreux.106 One day later SHAEF approved the immediate expansion of deliveries by air up to 2,000 tons per day to the Le Mans area, although it had little expectation at first that deliveries could average more than 1,000 tons. SHAEF tentatively limited the use of aircraft for this purpose to ten days—that is, until 25 August.107

The SHAEF offer proved timely indeed. On 15 August Third Army was already nearing the Seine and was experiencing critical shortages of many items, particularly gasoline. On the very day on which the SHAEF authorization was made it therefore requested daily air shipment of at least 1,500 tons of supplies directly to airfields in the army area.108 In view of its extended position and the speed of its advance, Third Army’s needs were obviously the most pressing, and it was natural that the expanded airlift capacity should be devoted initially to meeting that army’s requirements. Shipments under the new program did not get under way until 19 August, when the first deliveries, consisting of rations, were made to a newly

opened field at Le Mans.109 In the next few days deliveries averaged less than 600 tons per day, and it soon became apparent that the critical supply situation in the forward areas would not be appreciably relieved by 25 August, the date up to which the enlarged airlift had been authorized.

The entire logistic situation was actually worsening. On 20 August the Third Army had already started across the Seine and was operating with less than two units of fire and less than one day’s reserve of rations and gasoline under its immediate control. Both Third and First Armies were getting only the barest daily maintenance forward. The increasingly acute supply situation impelled Third Army on 22 August to ask that the airlift be extended an additional ten days.110

In forwarding this request to Supreme Headquarters, the 12th Army Group took the occasion to reinforce it with additional argument. It described the dire supply situation in both its armies and asserted that regardless of the bad weather and the construction difficulties at Le Mans, which had prevented full use of the available lift, supply by air had already been of unquestionable value. The army group was hopeful that some of the initial handicaps—particularly the scarcity of landing fields—would soon be overcome, for deliveries were shortly expected to begin at newly opened fields at Orleans. General Moses estimated that the need for air-transported supplies would continue at least until 10 September.111

Fully aware that the continued allocation of troop carrier and transport aircraft would hamper the training and preparations of the Allied airborne forces, SHAEF nevertheless decided to permit the airlift of supplies to continue, although at reduced capacity. On 25 August it directed the First Allied Airborne Army to prepare to make a daily allotment of 200 aircraft with a daily lift capacity of 500 tons beginning on 26 August. The allotment was to be increased to 400 craft with the return of aircraft (425 planes) which had been loaned to Allied forces in the Mediterranean for the southern France airborne operation.112

Up to 25 August the performance of the airlift had been something less than spectacular, although the 4,200 tons delivered in the first week undoubtedly aided in maintaining the momentum of the pursuit. Several factors had operated to frustrate the development of the airlift’s full potential. The lack of continental airfields imposed the greatest restriction at first, and backlogs of both loaded planes and requisitions developed. On 22 August 383 loaded C-47’s were held at U.K. airdromes for lack of forward terminal airfields, and CATOR was forced to ask the army group G-4 to indicate priorities for supplies ready for air delivery.113

Scarcities bred scarcities. Airfields for both tactical and administrative use were urgently needed. To restore captured fields and to build new ones, engineer materials had to be shipped in transport that was already desperately inadequate. Army group at one time found it necessary in the midst of the pursuit to allocate as much as

2,100 tons per day of the meager transportation resources for forward fighter field construction.114 The air forces were naturally reluctant to release tactical fields needed for their operations, and supply operations were therefore restricted to fields not occupied by tactical air units, or to fields which they had abandoned or which were unsuitable for tactical aircraft.115 Meanwhile, imperfect “mounting” arrangements in the United Kingdom, aggravated by a shortage of trucks, created delays in the loading of planes, further hindering the optimum development of the airlift in its early stages.