Chapter 2: Diversionary Assaults

Treasury Island Landings1

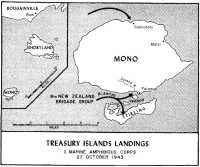

If the initial plans for the direct assault on the Buin area or the Shortlands had been carried out, the two small islands of the Treasury Group would have been bypassed and left in the backwash of the campaign. Instead, with the change in plans to strike directly at Empress Augusta Bay, the islands of Mono and Stirling became important as long-range radar sites and torpedo boat anchorages. Moreover, in an attempt to deceive the enemy as to the direction of the attack on Bougainville and convince him that the ultimate Allied aim might be the Buin area or the Shortlands, the seizure of the Treasurys was given added emphasis by being set as a preliminary to the Torokina landings. To help this deception succeed, reconnaissance patrols to the Shortlands and diversionary operations on the island of Choiseul—plus low-flying photo missions over the Shortlands—were scheduled by IMAC to increase the enemy’s conviction that the follow-up objective was the Shortlands.

This could have been a natural assumption by the enemy. The Treasurys are about 60 miles northwest of Vella Lavella and only 18 miles south of the Shortlands. While the size of the Treasurys limited consideration as a major target, Mono and Stirling were close enough to Shortland Island to cause the Japanese some concern that they might be used as handy stepping stones by SoPac forces. But then again, the Treasurys are only 75 miles from Cape Torokina—a fact which the Allies hoped might be lost on Bougainville’s defenders.

The Treasury Islands are typical of other small islands jutting out of the sea in the Solomons chain. Mono is a thickly forested prominence of volcanic origin, with abrupt peaks and hill masses more than 1,000 feet high in the southern part. These heights slope gradually in an everwidening fan to the west, north, and east coasts. The shores are firm, with few swamps, and rain waters drain rapidly through deep gorges. The island is small, about four miles north to south and less than seven miles lengthwise.

Stirling Island to the south is smaller, more misshapen. Fairly level, this island is about four miles long and varies from 300 yards to nearly a mile in width. There

are several small, brackish lakes inland, but the island is easily traversed and, once cleared of its covering forest, would be an excellent site for an airfield. Between these two islands is a mile or more of deep, sheltered water—one of the many anchorages in the Solomon Islands to bear the name Blanche Harbor. The combination of these features—airfield site, radar points, good anchorage—was the factor which resulted in the seizure of the Treasurys as part of the Bougainville operation.

Early information about the islands was obtained by an IMAC patrol which spent six days in the Treasurys in August, scouting the area, observing the movement of the Japanese defenders, and interrogating the natives. In this latter instance, the loyal and friendly people of the Treasurys were a remarkable contrast to the suspicious and hostile Bougainville inhabitants. Additional details were received from rescued aviators who found Mono Island a safe hiding place after their planes had been forced down by damage incurred in raids over Buin and the Shortlands. This first-hand intelligence was augmented by aerial photographs. The reports and photos indicated that the best landing beaches were inside Blanche Harbor, on opposite shores of Mono and Stirling. The only beaches suitable for LSTs, however, were on Mono between the Saveke River and a small promontory, Falamai Point.

As limited as this information was, the amount of intelligence on the enemy dispositions on the two islands was even more meager. The Japanese strength was estimated at 135 men, lightly armed. These were bivouacked near Falamai but maintained a radio station and observation posts in various areas. Natives reported that much of the time the Japanese moved about Mono armed only with swords or hand guns. Stirling Island was apparently undefended.

The 8th New Zealand Brigade Group, attached to I Marine Amphibious Corps for the seizure and occupation of these islands, arrived at Guadalcanal from New Caledonia in mid-September. Although the New Zealanders would form the bulk of the assault troops, the GOODTIME operation was IMAC-directed and IMAC-supported. The landing force comprised about 7,700 officers and men, of whom about 1,900 were from I Marine Amphibious Corps support troops—antiaircraft artillery, construction battalions, signal, and boat pool personnel. Marines attached to the brigade task organization included a detachment from the IMAC Signal Battalion and an air-ground liaison team from General Harris’ ComAirNorSols headquarters.

On 28 September, Brigadier Row, the landing force commander, was informed of the general nature of the GOODTIME operation, and planning in conjunction with Admiral Fort began immediately, although there was only enough information available to the commanders of the task group and the landing force to formulate a plan in broad outline. The task was far from easy, for the Southern Force was confronted with the same logistical and transportation problems that faced the Empress Augusta Bay operation.

Fort and Row decided that the main assault would be made in the area of Falamai, where beaches were suitable for LSTs. Stirling Island would be taken concurrently for artillery positions. No other landings were planned; but after Row was informed that the long-range radar would have to be positioned on the northern side of Mono to be of benefit to

Map 12: Treasury Islands Landings, I Marine Amphibious Corps, 27 October 1943

the Bougainville operation, another landing at Soanotalu on the north coast was written into the plans.

Final shipping allocation to Fort’s Southern Force included 31 ships of six different types—8 APDs, 8 LCIs, 2 LSTs, and 3 LCTs for landing troops and supplies, 8 LCMs and 2 APCs for heavy equipment and cargo. The limited troop and cargo capacity of this collection of ships and landing craft restricted the Southern Force’s ability to put more than a minimum of troops and supplies ashore initially, but this problem was solved by reducing the strength of the brigade’s battalions and limiting the number of artillery weapons, motor transport, and engineering equipment in the first echelon. The brigade’s assault units included 3,795 troops with 1,785 tons of supplies and equipment. Succeeding echelons were scheduled to sail forward at intervals of five days.

The final plans, issued by Row’s headquarters on 21 October, directed the 29th and 36th Battalions to land nearly abreast near Falami Point, with the 34th Battalion landing on Stirling Island. Simultaneously, a reinforced infantry company accompanied by radar personnel and

Seabees would go ashore at Soanotalu in the north. The two battalions on Mono would then drive across the island to link up with the Soanotalu landing force while naval base construction got underway at Stirling.

The initial landings in Blanche Harbor were to be covered by a naval gunfire support group of two destroyers, the Pringle and Philip. Liaison officers of IMAC planned the gunfire support, as the New Zealand officers had no experience in this phase of operations. While the brigade group expected to have no trouble in seizing the islands, the naval support was scheduled to cover any unforeseen difficulties. The gunfire plan called for the two destroyers to fire preparation salvos from the entrance to Blanche Harbor before moving in toward the beaches with the landing waves to take targets under direct fire. The IIIPhibFor, however, took a dim view of risking destroyers in such restricted waters. The desired close-in support mission was then assigned to the newly devised LCI(G)—gunboats armed with three 40-mm, two 20-mm, and five .50 caliber machine guns—which were making their first appearance in combat. Two of these deadly landing craft were to accompany the assault waves to the beaches.

After one final practice landing on Florida Island, the brigade group began loading supplies and embarking troops for the run to the target area. Admiral Fort’s Southern Force was divided into five transport groups under separate commanders, and these groups departed independently when loaded. The slower LSTs and LCMs left first, on the 23rd and 24th of October, and were followed the next day by the LCIs. The APDs sailed on 26 October.

The Southern Force departed with a message which delighted the New Zealanders as typical of the remarks to which Americans at war seemed addicted: “Shoot calmly, shoot fast, and shoot straight.”2

At 0540 on the 27th, the seven APDs of the first transport group lay to just outside the entrance to Blanche Harbor and began putting troops over the side into landing craft. Heavy rain and overcast weather obscured the beaches, but the preassault bombardment by the Pringle and Philip began on schedule. The USS Eaton moved to the harbor’s mouth and took up station as fighter-director ship as the destroyers registered on Mono Island. The firing was accomplished without assistance of an air spotter, who later reported radio failure at the critical moment. This probably accounts for the disappointing results of the preparatory bombardments, which proved to be of little value except to boost the morale of the assault troops. The Pringle’s fire was later declared to be too far back of the beach area to be helpful, and the bombardment by the Philip left a great deal to be desired in accuracy, timing, and quantity.

A fighter cover of 32 planes arrived promptly on station over the Treasurys at 0600, and, under this protective screen, the assault waves formed into two columns for the dash through Blanche Harbor to the beaches. Unexpectedly, enemy machine gun fire from Falamai and Stirling greeted the assault boats as they ploughed through the channel. At 0623, just three minutes before the landing craft nosed into the beaches on opposite sides of the harbor, the preassault cannonading ceased; and the two LCI gunboats—one on each

flank of the assault wave—took over the task of close support for the landing forces. At least one 40-mm twin-mount gun, several machine guns, and several enemy bunkers were knocked out by the accurate fire of these two ships. Promptly at 0626, the announced H-Hour, New Zealand troops went ashore on Mono and Stirling.

At Falamai, the 29th and 36th Battalions moved inland quickly against light rifle and machine gun fire, mostly from the high ground near the Saveke River. Casualties in the first wave were light—one New Zealand officer and five sailors wounded—and the second wave had no casualties.

The New Zealanders began to widen the perimeter as more troops were unloaded. At 0735, enemy mortar and medium artillery fire registered on the beach area, causing a number of casualties and disrupting unloading operations. Both LSTs were hit, with one ship reporting 2 dead and 18 wounded among the sailors and soldiers aboard. The other ship reported 12 wounded. Source of the enemy fire could not be determined. The Eaton, with Admiral Fort on board, ignored a previous decision not to enter Blanche Harbor and resolutely steamed between the two islands. This venture ended, however, when enemy planes were reported on the way, and the Eaton reversed course to head for more maneuvering room outside the harbor. Assured that the air raid was a false alarm, the destroyer returned to Blanche Harbor and added its salvos to those of the LCI gunboats. This fire, directed at likely targets, abruptly ended the Japanese exchange.

By 1800, the two battalions had established a perimeter on Mono Island and were dug in, trying to find some comfort in a dismal rain which had begun again after a clear afternoon. Evacuation of casualties began with the departure of the LSTs. With the exception of one LST, which still had 34 tons of supplies aboard when it retracted, all ships and landing craft had been unloaded and were on their way back to Guadalcanal by the end of D-Day. The casualties were 21 New Zealanders killed and 70 wounded, 9 Americans killed and another 15 wounded.

The landings at Stirling and Soanotalu were uneventful and without opposition. There were no casualties at either beachhead. At Stirling, the 34th Battalion immediately began active patrolling as soon as the command was established ashore. The Soanotalu landings proceeded in a similarly unhindered manner. A perimeter was established quickly, and bulldozers immediately went to work constructing a position for the radar equipment which was to arrive the next day.

The fighter cover throughout the day had shielded the troops ashore from enemy air attacks. The escorting destroyers, however, were hit by an enemy force of 25 medium and dive bombers at about 1530, and the USS Cony took two hits. Eight crewmen were killed and 10 wounded. The fire from the destroyer screen and the fighter cover downed 12 of the enemy planes. That night the bombers returned to pound the Mono Island side of Blanche Harbor and, in two raids, killed two New Zealanders and wounded nine.

Action along the Falamai perimeter the night of 27 October was concentrated mainly on the left flank near the Saveke River, the former site of the Japanese headquarters, and several attacks were beaten back. The following day, patrols moved forward of the perimeter seeking

the enemy, and one reinforced company set out cross-country to occupy the village of Malsi on the northeast coast. There was little contact. Japanese ground activity on the night of the 28th was light, and enemy air activity was limited to one low-level strafing attack and several quick bombing raids—all without damage to the brigade group.

By 31 October, the entire situation was stable. The perimeter at Falamai was secure, Malsi had been occupied without opposition, and radar equipment at Soanotalu had been installed and was in operation. With the arrival of the second echelon on 1 November, the New Zealanders began an extensive sweep of the island to search out all remaining enemy troops on the island. The going was rough in the high, rugged mountain areas, but, by 5 November, enemy stragglers in groups of 10 to 12 had been tracked down and killed. The New Zealanders lost one killed and four wounded in these mop-up operations.

Undisturbed for some time, the perimeter at Soanotalu was later subjected to a number of sharp attacks, each one growing in intensity. The Soanotalu force was struck first on 29 October by small groups of Japanese who were trying to reach the beach after traveling across the island from Falamai. These attacks continued throughout the afternoon until a final charge by about 20 Japanese was hurled back. Construction of the radar station continued throughout the fighting. Enemy contact on the next two days was light, and the first radar station was completed and a second one begun.

On the night of 1 November, a strong force of about 80 to 90 Japanese suddenly struck the perimeter in an organized attack, apparently determined to break through the New Zealand defense to seize a landing craft and escape the island. The fight, punctuated by grenade bursts and mortar fire, raged for nearly five hours in the darkness. One small group of enemy penetrated the defenses as far as the beach before being destroyed by a command group. About 40 Japanese were killed in the attack. The Soanotalu defenders lost one killed and nine wounded. The following night, 2 November, another attempt by a smaller Japanese force was made and this attack was also beaten back. This was the last organized assault on the Soanotalu force, and the remainder of the Japanese on the island were searched out and killed by the New Zealand patrols striking overland.

By 12 November, the New Zealanders had occupied the island. Japanese dead counted in the various actions totaled 205; the New Zealanders took 8 prisoners. It is doubtful that any Japanese escaped the island by native canoe or swimming. In addition, all enemy weapons, equipment, and rations on the island were captured. The Allied casualties in this preliminary to the Bougainville operation were 40 New Zealanders killed and 145 wounded. Twelve Americans were killed and 29 wounded.

During the period of fighting on Mono Island, activity on Stirling was directed toward the establishment of supply dumps, the building of roads, and the construction of advance naval base and boat pool facilities. Although several minor enemy air raids damaged installations in the early phases of the operation, the landing at Empress Augusta Bay diverted the attention of the enemy to that area and ended all Japanese attempts to destroy the force in the Treasurys.

Raid on Choiseul Island3

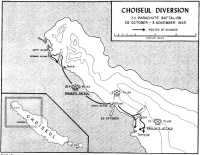

If the Japanese had opportunity to speculate on the significance of the Treasurys invasion, the problem may have been complicated a few hours later by a landing of an Allied force on the northwest coast of Choiseul Island, just 45 miles from the southeastern coast of Bougainville. The landing was another ruse to draw Japanese attention from the Treasurys, point away from the Allies’ general line of attack, and divert the enemy’s interest—if not effort—toward the defense of another area. More specifically, the Choiseul diversion was calculated to convince the Japanese that the southern end of Bougainville was in imminent danger of attack from another direction. The salient facts which the Allies hoped to conceal were that the real objective was Empress Augusta Bay, and that the Choiseul landing force consisted only of a reinforced battalion of Marine parachute troops.

Actually, the raid on Choiseul was a small-scale enactment of landing plans which had been discarded earlier. Choiseul was considered as a possible objective for the main Northern Solomons attack; but when the decision was made that the Allied attack would strike directly amidships on the western coast of Bougainville, the Choiseul idea was dropped. Then, when the suggestion was advanced by Major James C. Murray, IMAC Staff Secretary, that, because of the size and location of Choiseul, a. feint toward that island might further deceive the Japanese as to the Allies’ intentions, the diversionary raid was added to the Northern Solomons operation.

Choiseul is one of the islands forming the eastern barrier to The Slot; and as one of the Solomon Islands, it shares the high rainfall total, the uniform high heat and humidity common to other islands of the chain. About 80 miles long and 20 miles wide at the widest point, Choiseul is joined by reefs at the southern end of two small islands (Rob Roy and Wagina) which seems to extend Choiseul’s length another 20 miles. The big island is not as rugged as Bougainville and the mountain peaks are not as high, but Choiseul is fully as overgrown and choked with rank, impenetrable jungle and rain forest. The mountain ranges in the center of the island extend long spurs and ridges toward the coasts, thus effectively dividing the island into a series of large compartments. The beaches, where existent, vary from wide, sandy areas to narrow, rocky shores with heavy foliage growing almost to the water’s edge. Other compartments end in high, broken cliffs, pounded by the sea.

The island was populated by nearly 5,000 natives, most of whom (before the war) were under the teachings of missionaries of various faiths. With the exception of a small minority, these natives remained militantly loyal to the Australian government and its representatives. As a result,

coastwatching activities on Choiseul were given valuable assistance and protection.

Combat intelligence about the island was obtained by patrols which scouted various areas. One group, landed from a PT boat on the southwest coast of Choiseul, moved northward along The Slot side of the island toward the Japanese base at Kakasa before turning inland. After crossing the island to the coastwatcher station at Kanaga, the patrol was evacuated by a Navy patrol bomber on 12 September after six days on the island.

Two other patrols, comprising Marines, naval officers, and New Zealanders, scouted the northern end of the island and Choiseul Bay for eight days (22-30 September) before being withdrawn. Their reports indicated that the main enemy strength was at Kakasa where nearly 1,000 Japanese were stationed and Choiseul Bay where another 300 troops maintained a barge anchorage. Several fair airfield sites were observed near Choiseul Harbor, and a number of good beaches suitable for landing purposes were marked. Japanese activity, the patrols noted, was generally restricted to Kakasa and Choiseul Bay.4

During the enemy evacuation of the Central Solomons, Choiseul bridged the gap between the New Georgia Group and Bougainville. The retreating Japanese, deposited by barges on the southern end of Choiseul, moved overland along the coast to Choiseul Bay where the second half of the barge relay to Bougainville was completed. This traffic was checked and reported upon by two active coastwatchers, Charles J. Waddell and Sub-Lieutenant C. W. Seton, Royal Australian Navy, who maintained radio contact with Guadalcanal.

Seton, on 13 October, reported the southern end of Choiseul free of Japanese, but added that at least 3,000 to 4,000 enemy had passed Bambatana Mission about 35 miles south of Choiseul Bay. On 19 October, the coastwatcher reported that the enemy camps in the vicinity of Choiseul Bay and Sangigai (about 10 miles north of Bambatana Mission) held about 3,000 Japanese who were apparently waiting for barge transportation to Bougainville. Seton indicated that the Japanese were disorganized, living in dispersed huts, and were short of rations. They had looted native gardens and searched the jungle for food. Further, the Japanese were edgy. All trails had been blocked, security had been tightened, and sentries fired into the jungle at random sounds.5

After this information was received at IMAC headquarters, Vandegrift and Wilkinson decided that a diversionary raid on Choiseul would be staged. On 20 October, Lieutenant Colonel Robert H. Williams, commanding the 1st Marine Parachute Regiment, and the commanding officer of his 2nd Battalion, Lieutenant Colonel Victor H. Krulak, were summoned from Vella Lavella to Guadalcanal. At IMAC headquarters, Williams and Krulak conferred with Vandegrift and his staff. The orders to Krulak were simple: Get ashore on Choiseul and make as big a demonstration as possible to convince the

Map 13: Choiseul Diversion, 2nd Parachute Battalion, 28 October - 3 November 1943

Japanese that a major landing was in progress. In addition, reconnaissance would be conducted to determine possible sites for a torpedo boat patrol base.

The IMAC operation order, giving the code name BLISSFUL to the Choiseul diversion, was issued on 22 October. Based on information and recommendations from Seton, the Marines’ landing was set for the beaches in the vicinity of Voza village, about midway between Choiseul Bay and Bambatana Mission. There the beaches were good, friendly natives would help the invading forces, and there reportedly were no enemy troops. Moreover, it was firmly astride the main route of evacuation of the Japanese stragglers from Kolombangara and points south. After receiving the order, Krulak went to the airstrip on Guadalcanal, and, while waiting for a plane to take him back to his command, wrote out the operation order for his battalion’s landing.

This was to be the first combat operation of the 2nd Battalion as well as its first amphibious venture. Although equipped and trained for special assignments behind enemy lines, these Marines—known as Paramarines to their comrades—never chuted into action because suitable objectives were usually beyond the range of airborne troops and the necessary transport planes were in chronically short supply. The 1st Parachute Battalion, however, had taken Gavutu and Tanambogo Islands before going to Guadalcanal to take part in the defense of the airfield there in 1942. This battalion had then formed the nucleus for the present 1st Parachute Regiment, now consisting of three battalions in IMAC reserve at Vella Lavella. Each battalion, of three rifle companies each, was armed with a preponderance of light automatic and semi-automatic weapons. The nine-man squads in Lieutenant Colonel Krulak’s rifle platoons carried three Johnson light machine guns6 and six Johnson semi-automatic rifles; each company had, in addition, six 60-mm mortars.

Krulak’s return to his command set off a flurry of near-frenzied activity, since the battalion had a minimum of time for preparation. For the next four days, officers and men worked almost around the clock to assemble equipment, make final plans, and brief themselves on the task ahead. On the 24th, Coastwatcher Seton and two of his native guides arrived at Vella Lavella to meet Krulak’s officers and men and give them last-minute information. After being briefed by Seton, Krulak requested and was given authority by IMAC to operate in any direction on Choiseul, if consistent with his mission.

Equipment and supplies for the operation were presorted into four stacks; and late on the afternoon of the 27th of October the parachute battalion and its gear was embarked on board eight LCMs borrowed from the Vella Lavella boat pool. Krulak’s three companies were reinforced by a communications platoon, a regimental weapons company with mortars and light machine guns, and a detachment from an experimental rocket platoon (bazookas and rockets) from IMAC. Total battalion strength was 30 officers and 626 men. In addition, one naval officer accompanied the battalion for reconnaissance purposes related to the possible establishment of a torpedo boat base.

At dusk, when four APDs which had just completed the Treasury landings arrived

off Vella Lavella, the troops and equipment were transferred from the LCMs to the McKean, Crosby, Kilty, and Ward in a quick operation that was completed in less than 45 minutes. The destroyer division, with the USS Conway acting as escort, sailed from Vella Lavella at 1921. The Conway’s radar would locate the landing point in the dark.

Moving in column through the night, the convoy was sighted shortly after 2300 by an enemy snooper plane which dropped one bomb, scoring a near miss on the last APD in line. Shortly before midnight, at a point some 2,000 yards off the northwest coast of Choiseul, the convoy stopped, and a reconnaissance party in a rubber boat headed toward shore to scout the landing area. A signal light was to be shown if no enemy defenders were encountered. While waiting for the signal, Krulak ordered Companies F and G into the landing boats.

After waiting until 0019 (28 October), Company F headed toward the beach with Company G close behind. The operation order had directed Company G to make the initial assault, but the APDs had drifted apart and the Kilty with Company F embarked was closer to shore. Since no light on shore was yet discernible, the Marines expected opposition. The landing, however, was uneventful, and the patrol was waiting on shore. Observers on ship reported later that the light was visible at 0023, just four minutes after the parachute companies began the run for the beach. After setting the troops ashore, the landing craft immediately returned to the transports to bring in a load of supplies.7

A lone enemy plane detected the Conway standing patrol duty seaward, and dropped two bombs near the ship. The Conway, reluctant to draw attention to the landing, did not return the fire, and the enemy plane droned away. An Allied escort plane, assigned to protect the convoy against such attacks, drew considerable criticism, however, for not remaining low enough to spot such bombing runs.

Two hours after arrival in the area, the convoy reversed course and steamed back to Vella Lavella, leaving behind four landing craft (LCP(R)) with their crews for the battalion’s use. These craft were dispersed under the cover of overhanging mangroves near the offshore island of Zinoa, and the Marines turned to moving supplies off the beach. Seton, who landed on Choiseul with the battalion, disappeared into the bush and returned almost immediately with a group of native bearers. With their help, the Marines moved into the jungle. The transfer was none too soon; enemy reconnaissance planes appeared at dawn to bomb the area but without success.

Early on the morning of the 28th, a base of operations was established on a high jungle plateau about a mile to the northwest of Voza and outposts were set up on the beach north and south of the village. Security was established and wire communications installed. The plateau, behind natural barriers of rivers and high cliffs, was an ideal defensive spot and a necessary base camp for the heavy radio gear with which IMAC had equipped the parachute battalion.

During the day of 28 October, while the Marines established their camp, another enemy flight appeared and raked the beachhead with a strafing and bombing attack. The effect was wasted. The Marines had dispersed; their equipment had been moved; and good camouflage discipline had been observed. Too, the natives had obliterated every sign of a landing at Voza and established a dummy beachhead several miles to the north for the special benefit of Japanese planes seeking a target.

Informed by Seton’s guides that the Marine battalion, was bivouacked between a barge staging-replenishment base at Sangigai about eight miles to the south and an enemy outpost at the Warrior River about 17 miles to the north, Krulak on the morning of the 29th sent out reconnaissance patrols to the north and south. These groups were to locate trails, scout any enemy dispositions, and become familiar with the area.

Krulak personally led one patrol toward Sangigai, going overland toward the Vagara River which was about halfway between the Marine camp and the enemy base. While part of the patrol headed inland toward the high ground to the rear of Sangigai, to sketch the approaches to the village, the Marine comander led the rest of the patrol to the river. There the hidden Marines silently watched a group of about 10 Japanese unloading a barge; and since this appeared to be an excellent opportunity to announce the aggressive intentions of the Krulak force, the Americans opened fire. Seven of the Japanese were killed, and the barge sunk. Krulak’s section then returned to the base, followed shortly by the other half of the patrol. After the attack order was issued, a squad was sent back over the trail to the Vagara to hold a landing point for Krulak’s boats and to block the Japanese who might be following the Marines’ track. The patrol ran into a platoon of the enemy about three-quarters of a mile from the original Marine landing point and drove the Japanese off.8

At 0400 the following morning, 30 October, Krulak led Companies E and F, plus the rocket detachment, toward Voza for an attack on Sangigai. The barge base had been marked as a target since 22 October. To help him in his assault, and give the impression of a larger attacking force, Krulak requested a preparatory air strike on reported Japanese positions northwest of the base. Estimated enemy strength was about 150 defenders, although Seton warned that Sangigai could have been reinforced easily from the southwest since the Marines’ landing.

Krulak’s attack plans were changed at Voza, however, since one of the four boats had been damaged a few minutes earlier in an attack by Allied planes. The strafing ended when the fighter pilots discovered their error and apologized to the boat crews with a final pass and a clearly visible “thumbs-up” signal. The requested air strike at Sangigai hit at 0610 with better results. While 26 fighters flew escort, 12 TBFs dropped a total of more than two tons of bombs on enemy dispositions.

Unable to use the boats for passage to the Vagara, Krulak ordered his troops to begin a route march overland from Voza. Seton and his native guides led the way, followed by Company F (Captain Spencer H. Pratt) with a section of machine guns

and the rocket detachment. Company E (Captain Robert E. Manchester) and attached units followed. At about 1100, Japanese outposts on the Vagara opened fire on the Marine column. Brisk return fire from the parachutists forced the enemy pickets to withdraw towards Sangigai.

Following the envelopment plan he had formulated on the 29th, Krulak sent Company E along the coastline to launch an attack on Sangigai from that direction while the remainder of the force, under his command, moved inland to attack from the high ground to the rear and east of Sangigai. The assault was set for 1400, but as that hour drew near, the group in the interior found that it was still a considerable distance from the village. The mountainous terrain, tangled closely by jungle creepers and cut by rushing streams, slowed Krulak’s force, and, by H-Hour, the column was still not in position to make its attack effort. When the sound of firing came from the direction of Sangigai village, the second force was still moving towards its designated jump-off point. Seton’s natives, however, indicated that the enemy were just ahead.

Company E, moving along the beach, reached its attack position without trouble. Although the assault was delayed a few minutes, the company opened with an effective rocket spread and mortar fire. As the Marines moved forward, the Japanese defenders hastily withdrew, abandoning the base and the village to flee to the high ground inland. The Marine company entered the village without opposition.9

The enemy’s withdrawal to prepared positions inland fitted perfectly into Krulak’s scheme of maneuver. The Japanese moved from the village straight into the fire of Company F, and a pitched battle that lasted for nearly an hour ensued. An enveloping movement by the Marines behind the effective fire of light machine guns forced the Japanese into several uncoordinated banzai charges which resulted in further enemy casualties. As the Marines moved once more to turn the enemy’s right flank, the Japanese disengaged and about 40 survivors escaped into the jungle. A final count showed 72 enemy bodies in the area. Krulak’s force lost four killed. Twelve others, including Krulak and Pratt, were wounded.

Company E, possessors of Sangigai, had been busy in the interim. Manchester’s company, using demolitions, destroyed the village, the Japanese base and all enemy supplies, scuttled a new barge, and captured a number of documents, including a chart of enemy mine fields off southern Bougainville. The Marines then withdrew to the Vagara to board the four landing craft (the disabled boat had been repaired) for the return to Voza. Krulak’s force, after burying its dead, retraced its path to the Vagara and spent the night in a tight defensive perimeter.10 Early the

next morning, 31 October, the landing craft returned to carry the parachutists to Voza and the base camp.

With the battalion reassembled once more, the Marines prepared ambushes to forestall any Japanese retaliatory attacks, and aggressive patrols were pushed out along the coast to determine if the Japanese were threatening and to keep the enemy off balance and uncertain about Marine strength. A Navy PBY landed near Voza the following day to evacuate the wounded Marines and the captured documents; and, on the same day, in answer to an urgent request by Krulak, 1,000 pounds of rice for the natives and 250 hand grenades and 500 pounds of TNT were air dropped near Voza. Several brisk engagements between opposing patrols were reported on this day, 1 November, but the base camp was not attacked. Seton’s natives, however, reported that Sangigai had again been occupied by the Japanese.

After Krulak returned to the base camp on 31 October, his executive officer, Major Warner T. Bigger, led a patrol to Nukiki Village, about 10 miles to the north. No opposition was encountered. On the following day, 1 November, Bigger led 87 Marines from Company G (Captain William H. Day) toward Nukiki again to investigate prior reports of a large enemy installation on the Warrior River. Bigger’s instructions were to move from Nukiki across the Warrior River, destroying any enemy or bases encountered, and then move as far north as possible to bring the main Japanese base at Choiseul Bay under 60-mm mortar fire. Enemy installations on Guppy Island in Choiseul Bay were an alternate target.

The patrol moved past Nukiki without opposition, although the landing craft carrying the Marines beached continually in the shallow mouth of the Warrior River. Since the sound of the coxswains gunning the boats’ motors to clear obstructions was undoubtedly heard by any enemy in the area, Bigger ordered the Marines to disembark. The boats were then sent downriver to be hidden in a cove near Nukiki. Bigger’s force, meanwhile, left four men and a radio on the east bank of the river, and all excess gear including demolitions was cached. Mortar ammunition was distributed among all the Marines. The patrol then headed upriver along the east bank, and the Warrior was crossed later at a point considerably inland from the coast.

By midafternoon, the natives leading the patrol confessed to Bigger that they were lost. Although in the midst of a swamp, the Marine commander decided to bivouac in that spot while a smaller patrol retraced the route back to the Warrior River to report to Krulak by radio and to order the boats at Nukiki to return to Voza. In response to Bigger’s message, Krulak asked Seton if he had any natives more familiar with the country north of the Warrior River; the only man who had visited the region was sent to guide the lost Marines.

The smaller patrol bivouacked at the radio site on the night of 1-2 November and awoke the next morning to the realization that a Japanese force of about 30 men had slipped between the two Marine groups and that their small camp was virtually surrounded. Stealthily slipping past enemy outposts, the patrol members moved to Nukiki, boarded the boats, and returned to Voza. After hearing the patrol’s report, Krulak then radioed IMAC for fighter cover and PT boat support to

withdraw the group from the Choiseul Bay area.

Bigger was unaware of the activity behind him. Intent upon his mission, he decided to continue toward Choiseul Bay. After determining his position, Bigger ordered another small patrol to make its way to the river base camp and radio a request that the boats pick up his force that afternoon, 2 November. This second patrol soon discovered the presence of an enemy force to Bigger’s rear, and was forced to fight its way towards Nukiki. This patrol was waiting there when the landing craft returned to Nukiki.

The main force, meanwhile, followed the new guide to the coast and then turned north along the beach toward Choiseul Bay. Opposite Redman Island, a small offshore islet, a four-man Japanese outpost suddenly opened fire. The Marines quickly knocked out this opposition, but one Japanese escaped—undoubtedly to give the alarm.

Because any element of surprise was lost and thinning jungle towards Choiseul Bay provided less protection and cover for an attacking force, Bigger decided to execute his alternate mission of shelling Guppy Island. Jungle vegetation growing down to the edge of the water masked the fire of the 60-mm mortars, so Bigger ordered the weapons moved offshore. The shelling of Guppy was then accomplished with the mortars emplaced on the beach with part of the baseplates under water. The enemy supply center and fuel base was hit with 143 rounds of high explosives. Two large fires were observed, one of them obviously a fuel dump. Bigger’s force, under return enemy fire, turned around and headed back toward the Warrior River.

The Japanese, attempting to cut off Bigger’s retirement, landed troops from barges along the coastline; and the Marine force was under attack four separate times before it successfully reached the Warrior River. There the patrol set up a perimeter on the west bank and waited for the expected boats.

Several men were in the river washing the slime and muck of the jungle march from their clothing when a fusillade of shots from the opposite bank hit the Marine force. The patrol at first thought it was being fired upon by its own base camp, but when display of a small American flag drew increased fire, the Marines dove for cover. Heavy return fire from the Marine side of the river forced the enemy to withdraw. Seizing this opportunity, Bigger directed three Marines to swim across the Warrior to contact the expected boats and warn the rescuers of the ambush. Before the trio could reach the opposite shore, though, the Japanese returned to the fight, and only one survivor managed to return to the Marine perimeter.

Even as the fierce exchange continued, the Marines sighted the four boats making for the Warrior River from the sea. An approaching storm, kicking up a heavy surf, added to the difficulty of rescue. Under cover of the Marines’ fire, the landing craft finally beached on the west shore, and the Bigger patrol clambered aboard.

One boat, its motor swamped by surf, drifted toward the enemy shore but was stopped by a coral head. The rescue was completed, though, by the timely arrival of two PT boats—which came on the scene with all guns blazing.11 While the

patrol boats raked the jungle opposite with 20-mm and .50 caliber fire, the Marines transferred from the stalled craft to the rescue ships and all craft then withdrew. A timely rain squall helped shield the retirement. Aircraft from Munda and PT boats provided cover for the return to Voza.

The time for withdrawal of the battalion from Choiseul was near, however, despite the fact that Krulak’s force had planned to stay 8-10 days on the island. On 1 November, another strong patrol, one of a series sent out from the Voza camp to keep the enemy from closing in, returned to the Vagara to drive a strong Japanese force back towards Sangigai. From all indications, the Japanese defenders now had a good idea of the size of the Krulak force, and aggressive enemy patrols were slowly closing in on the Marines. Seton’s natives on 3 November reported that 800 to 1,000 Japanese were at Sangigai and that another strong force was at Moli Point north of Voza.

After the recovery of the Bigger patrol from Nukiki, IMAC asked Krulak to make a frank suggestion as to whether the original plan should be completed or whether the Marine battalion should be removed. The Cape Torokina operation was well underway by this time, and IMAC added in its message to Krulak that Vandegrift’s headquarters considered that the mission of the parachute battalion had been accomplished. Krulak, on 3 November, radioed that the Japanese aggressiveness was forced by their urgent need of the coastal route for evacuation, and that large forces on either side of the battalion indicated that the Japanese were aware of the size of his force and that a strong attack, probably within 48 hours, was likely. The Marine commander stated that he had food for seven days, adequate ammunition, and a strong position; but that if IMAC considered his mission accomplished, he recommended withdrawal.

Commenting later on his situation at this time, Krulak remarked:–

As a matter of fact, I felt we’d not possibly be withdrawn before the Japs cut the beach route. However, we were so much better off than the Japs that it was not too worrisome (I say now!) The natives were on our side—we could move across the island far faster than the Japs could follow, and I felt if we were not picked up on the Voza side, we could make it on the other side. Seton agreed, and we had already planned such a move. Besides that we felt confident that our position was strong enough to hold in place if necessary.12

On the night of 3 November, three LCIs appeared offshore at a designated spot north of Voza to embark the withdrawing Marines. In order to delay an expected enemy attack, the Marines rigged mine fields and booby traps. During the embarkation, the sounds of exploding mines were clearly audible. Much to the parachutists’ amusement, the LCI crews nervously tried to hurry embarkation, expecting enemy fire momentarily. Krulak’s battalion, however, loaded all supplies and equipment except rations, which were given to the coastwatchers and the natives. Embarkation was completed in less than 15 minutes, and, shortly after dawn on the 4th of October, the Marine parachute battalion was back on Vella Lavella.

Krulak’s estimate of the Japanese intentions was correct. Within hours of the Marines’ departure, strong Japanese forces closed in on the area where the parachute battalion had been camped. The enemy had been surprised by the landing

and undoubtedly had been duped regarding the size of the landing force by the swift activity of the battalion over a 25-mile front. Then, after the operation at Empress Augusta Bay got underway, the Choiseul ruse became apparent to the Japanese, who began prompt and aggressive action to wipe out the Marine force. The continued presence of the Allied group on Choiseul complicated the evacuation program of the Japanese, and, once aware of the size of the Krulak force, the enemy lost no time in moving to erase that complication.

Before the battalion withdrew, though, it had killed at least 143 Japanese in the engagement at Sangigai and the Warrior River, sunk two barges, destroyed more than 180 tons of stores and equipment, and demolished the base at Sangigai. Unknown amounts of supplies and fuel had been blasted and burned at Guppy Island. Mine field coordinates shown on the charts captured at Sangigai were radioed to the task force en route to Cape Torokina, vastly easing the thoughts of naval commanders who had learned of the existence of the mines but not their location. Later, the charts were used to mine channels in southern Bougainville waters that the Japanese believed to be free of danger.

The destruction of enemy troops and equipment on Choiseul was accomplished at the loss of 9 Marines killed, 15 wounded, and 2 missing in action. The latter two Marines were declared killed in action at the end of the war.13

The effect of the diversionary attack upon the success of the Cape Torokina operation was slight. The Japanese expected an attack on Choiseul; the raid merely confirmed their confidence in their ability to outguess the Allies. In this respect, the Japanese were guilty of basing their planning on their opponents’ intentions, not the capabilities. There is little indication that enemy forces in Bougainville were drawn off balance by the Choiseul episode, and enemy records of that period attach little significance to the Choiseul attack.

This may be explained by the fact that the main landing at Cape Torokina took place close on the heels of Krulak’s venture and the ruse toward Choiseul became apparent before the Japanese reacted sufficiently to prepare a counterstroke to it. Certainly, the size and scope of the landing operations at Empress Augusta Bay were evidence enough that Choiseul was only a diversionary effort.

The Japanese14

Enemy reaction to the Allied moves was a bit slow. The Japanese knew that an offensive against them was brewing; what they could not decide was where or when. The Seventeenth Army was cautioned again to keep a watchful eye on Kieta and

Buka, and General Hyakutake in turn directed the 6th Division to maintain a firm hold on Choiseul as well as strong positions in the Shortland Islands. Then, the Japanese defenders on Bougainville waited for the next developments.

After the Allied landings in the Treasurys, the Japanese thinking crystallized: Munda was operational; Vella Lavella was not. Therefore, the only targets within range of New Georgia were the Shortlands or Choiseul. And based upon this reasoning, the Allies scarcely would attempt a landing on Bougainville before staging bases on Mono or Choiseul were completed. Reassured by this assumption, the Japanese relaxed, confident that the next Allied move would come during the dark quarters of the moon—probably late in November.

With the Allied move toward Choiseul, the Japanese were more convinced that the Allied pattern was predictable. With a firm foothold on Mono and Choiseul, the Allies would now move to cut Japanese lines and then land on the southern part of Bougainville in an attempt to seize the island’s airfields. Basing their estimates on the increased number of Allied air strikes on Buka and the Shortlands, the Bougainville defenders decided that these were the threatened areas. All signs pointed to a big offensive soon—probably, the Japanese agreed—on 8 December, the second anniversary of the declaration of war.

The enemy had no hint that such an unlikely area as Empress Augusta Bay would be attacked. The defense installations were concessions to orders directing that the western coast be defended, and the troops at Mosigetta—the only force capable of immediate reinforcement to the Cape Torokina area—were alerted only to the possibility that they might be diverted on short notice to the southern area to defend against an assault there.

Japanese sea and air strength was likewise out of position to defend against the Bougainville thrust. Admiral Mineichi Koga, commander in chief of the Combined Fleet at Truk, had decided earlier to reinforce Vice Admiral Jinichi Kusaka’s Southeast Area Fleet and the land-based planes of the Eleventh Air Fleet at Rabaul so that a new air campaign could be aimed at the Allies in the South Pacific. This operation, Ro, to start in mid-October, was to short-circuit Allied intentions by cutting supply lines and crushing any preparations for an offensive. To Kusaka’s dwindling array of fighters, bombers, and attack planes, Koga added the planes from the carriers Zuikaku, Shokaku, and Zuiho—82 fighters, 45 dive bombers, 40 torpedo bombers, and 6 reconnaissance planes.

Koga’s campaign, though, was delayed. Allied radio traffic indicated that either Wake or the Marshall Islands would be hit next, and to counter this threat in the Central Pacific, Koga sent his fleet and carrier groups toward Eniwetok to set an ambush for the Pacific Fleet. After a week of fruitless steaming back and forth, the Japanese force returned to Truk, and the carrier groups moved on to Rabaul. The Japanese admiral had at first decided to deliver his main attack against New Guinea, but the Treasurys landings

caused him to swerve towards the Solomons. Then, when Allied activities between 27 October and 1 November dwindled, the fleet again turned toward New Guinea to take up the long-delayed Ro operation. The elements of the Japanese fleet reached the area north of the Bismarcks on 1 November, just in time to head back towards the Solomons to try to interrupt the landings at Cape Torokina.