Chapter 3: Assault on Cape Torokina

“... The Troops are Magnificent.”1

The Northern Landing Force arrived off Empress Augusta Bay for the assault of Cape Torokina shortly after a bright dawn on 1 November, D-Day. The approach to the objective area had been uneventful. After rendezvousing near Guadalcanal, the transports steamed around the southern and western coasts of Rendova and Vella Lavella toward the Shortland Islands. ComAirSols fighter planes provided protection overhead and destroyer squadrons screened the flanks. Submarines ranged ahead of the convoy to warn of any interception attempt by the enemy.

When darkness fell on 31 October, the convoy abruptly changed course and, picking up speed, started the final sprint toward Empress Augusta Bay. Mine sweepers probed ahead for mine fields and uncharted shoals, while Navy patrol bombers and night fighters took station over the long line of transports. Eight air alerts were sounded during the night. Each time the night fighters, directed by the destroyers, intercepted and chased the enemy snooper planes away from the convoy. The amphibious force, moving direct as an arrow toward the coast of Bougainville, was never attacked.

Nearing Empress Augusta Bay, the convoy slowed so that the final movement into the objective area could be made in daylight. General quarters was sounded at 0500, and, after the sun came up, the assault troops on the transports could see the dark shoreline and rugged peaks of Bougainville directly ahead. Only a thin cloud mist hung over the island, scant concealment for enemy planes which could have been waiting to ambush the amphibious force. The element of surprise, which had been zealously guarded during all preparations for the offensive, apparently had been retained. The conflicting

reports by Japanese snooper planes of task forces observed at various points from Buka to the Shortlands and Vella Lavella had the general effect of confusing the Japanese.2

At 0545, mine sweepers and the destroyer Wadsworth opened fire on the beaches north of Cape Torokina to cover their own mine-sweeping operations. As the Wadsworth slowly closed to within 3,000 yards to fire directly into enemy installations, the busy mine sweepers scouted the bay. Thirty minutes later, advised that no mines had been found, the transports moved into the area. Off Cape Torokina, each APA shelled the promontory with ranging 3-inch fire before turning hard to port to take Puruata Island under fire with 20-mm guns. At 0645, the eight troop transports were on line about 3,000 yards from the beach and parallel to the shoreline. Behind them, in a similar line, were the four cargo transports with the destroyer squadrons as a protective screen seaward.

On board the transports, observers peered anxiously toward the beaches near the Laruma River. A two-man patrol had been landed on Bougainville on D minus 4 days (27 October) with the mission of radioing information or lighting a signal fire near the Laruma if the Cape Torokina area was defended by less than 300 Japanese. Concern mounted as H-Hour approached without the expected message or signal. The alternatives were that the patrol had been captured or that the cape area was unexpectedly reinforced by the enemy. Because the landing waves had been organized to handle cargo and supplies at the expense of initial combat strength, any change in the enemy situation at this late date was cause for worry. H-Hour, set for 0715, was postponed for 15 minutes on signal from Admiral Wilkinson, but the landing was ordered as planned. (The patrol later reported unharmed, citing radio failure and terrain difficulties for the lack of messages.)

Preparatory fires by the main support group began as soon as visibility permitted identification of targets. From their firing positions south of the transport area, the Anthony and Sigourney—and later the Wadsworth—poured 5-inch shells into Puruata Island and the beaches north of Cape Torokina. The Terry, on the left flank of the transport area, fired into known enemy installations on the north shoulder of the cape. The effect was a crossfire, centered on the beaches north of Cape Torokina. This indirect fire on area targets was controlled by spotter aircraft.

Debarkation of troops began after the transports anchored in position and while the preassault bombardment crashed along the shoreline. The order to land the landing force was given at 0645, and within minutes assault craft were lowered into the sea, and embarkation nets tossed over the side of the transports. Marines clambered down the nets into the boats, and, as each LCVP was loaded, it joined the circling parade of landing craft in the rendezvous circles, waiting for the signal to form into waves for the final run to the beach. Nearly 7,500 Marines, more than half of the assault force, were boated for the simultaneous landing over the 12 beaches.

At 0710, the gunfire bombardment shifted to prearranged targets, and five minutes later the first boats from the

Landing craft is lowered over the side of the APA George Clymer on D-Day at Bougainville while Marines watch in the foreground. (USN 80-G-55810)

APAs on the south flank of the transport area started for shore. The support ships continued to shoot at beach targets until 0721, when the shelling was lifted to cover targets to the rear of the immediate shoreline. As the fire lifted, 31 torpedo and scout bombers from Munda streaked over the beaches, bombing and strafing the shoreline just ahead of the assault boats. The planes, from VMTB-143, -232, and -233, and VMSB-144, were covered by VMF-215 and -221 and a Navy fighter squadron, VF-17.3 The air strike lasted until 0726, cut short four minutes by the early arrival of the first landing craft at the beaches.

The 9th Marines (Colonel Edward A. Craig) landed unopposed over the five northernmost beaches—RED 3, RED 2, YELLOW 4, RED 1, and YELLOW 3. Although no enemy fire greeted the approach of the boats, the landing was unexpectedly hazardous. Rolling surf, higher and rougher than anticipated, tossed the landing craft at the beaches. The LCVPs and the LCMs, caught in the pounding breakers, broached to and were smashed against shoals, the beach, and other landing craft. The narrow shoreline, backed by a steep 12-foot embankment, prevented the landing craft from grounding properly, and this further complicated the landing.

Some boats, unable to get near the shore because of rough surf and wrecked boats, unloaded the Marines in chest-deep water. Other Marines, in LCVPs with collision-damaged ramps, jumped over the sides of the boats and made their way to shore. In spite of these difficulties, the battalion landing teams managed to get ashore quickly, and, by 0750, several white parachute flares fired by the assault troops indicated to observers on board ship that the landing was successful.

Once ashore, combat units of the 9th Marines completed initial reorganization and moved inland to set up a perimeter around the five beaches. Active patrolling was started immediately, and a strong outpost was set up on the west bank of the Laruma River. Other Marines remained on the beach to help unload the tank lighters and personnel boats which continued to arrive despite the obvious inadequacy of the beaches and the difficult surf. At least 32 boats were wrecked in the initial assault and lay smashed and awash along the beach. By mid-morning, hulks of 64 LCVPs and 22 LCMs—many of them beyond repair—littered the five beaches.4

The landings on the six southern beaches (YELLOW 2, BLUE 3, BLUE 2, GREEN 2, YELLOW 1, and BLUE 1) and the single beach on Puruata Island (GREEN 1) were in stark contrast to the northern zone. Enemy resistance in this area was evident almost as soon as the boat groups from the right-flank transports came within range. The 2nd and 3rd Battalions of Colonel George W. McHenry’s 3rd Marines landed on the three beaches south of the Koromokina River against small-arms fire. Surf was high but not difficult, and no boats were lost. The Marines, disembarking without delay, sprinted across the narrow beach to take cover in the jungle. Reorganization was completed quickly, and the battalions started to dig out the small number of Japanese defenders attempting to hold back the assault from hastily

prepared positions. In a few minutes, the scattered enemy in the area had been killed, and sniper patrols began moving inland. Contact was established with the 9th Marines on the left, but a wide swamp prevented linkup with the 2nd Raider Battalion on the right.

The raiders, led by Major Richard T. Washburn, went ashore in the face of heavy machine gun and rifle fire from two enemy bunkers and a number of supporting trenches about 30 yards inland. Japanese defenders were estimated at about a reinforced platoon. After the first savage resistance, the enemy fire slackened as the raiders blasted the bunkers apart to kill the occupants. Other enemy soldiers retreated into the jungle. Only after the beach area was secured did the raiders discover that the regimental executive officer, Lieutenant Colonel Joseph W. McCaffery, had been fatally wounded while coordinating the assault of combat units against the enemy dispositions.5

Extensive lagoons and swampland backing the narrow beach limited reconnaissance efforts, and reorganization of the assault platoons and companies was hindered by constant sniper fire. Despite these handicaps, the raiders pushed slowly into the jungle and, by 1100, had wiped out all remaining enemy resistance. Raider Company M, attached to the 2nd Raider Battalion for the job of setting up a trail block farther inland to stall any enemy attempt to reinforce the beachhead, moved out along the well-marked Mission Trail and was soon far out ahead of the raider perimeter.

The 1st Battalion of the 3rd Marines hit the hot spot of the enemy defenses. As the waves of boat groups rounded the western tip of Puruata Island, they were caught in a vicious criss-cross of machine gun and artillery fire from Cape Torokina and Puruata and Torokina Islands. Heading toward the extreme right of the landing area over beaches which included Cape Torokina, the 1st Battalion ploughed ashore straight through this deadly crossfire. An enemy 75-mm artillery piece, which had tried earlier to hit one of the transports, remained under cover during the aerial bombing and opened fire again only after the assault boats reached a point some 500 yards offshore. Its location was such that all boats heading toward the beach had to cross the firing lane of this gun.6

One of the first casualties in the assault waves was the LCP carrying the boat group commander. The command boat, blasted by a direct hit, sank immediately. The explosion resulted in dispersion, disorganization, and confusion among the boat group. In a split second, the approach formation was broken by landing craft taking evasive action to avoid the antiboat fire.

The result was a complete mixup of assault waves. A total of six boats were hit within a few minutes; only four of them managed to make the beach. As the first waves of boats grounded on the beaches, the Japanese opened up with machine gun and rifle fire, and mortar bursts began to range along the shoreline. A withering fire poured from a concealed complex of log and sand bunkers connected by a series of rifle pits and trenches.

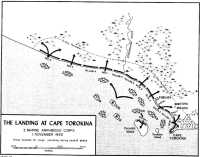

Map 14: The Landing at Cape Torokina, I Marine Amphibious Corps, 1 November 1943

The enemy emplacements, barely above ground level and hidden beneath the tangled underbrush along the shoreline, were sited to cover the beaches and bay with interlocking bands of fire. The preassault bombardment by gunfire ships and planes had not knocked out the enemy fortifications; in most cases it had not even hit them.

The Marines, with all tactical integrity and coordination lost, plunged across the thin strip of beach to take cover in the jungle. An orderly landing against such concentrated fire had been impossible. After the scrambling of the assault waves, units from the battalion landing team had gone ashore where possible and practically every unit was out of position. Contributing to this confusion was the fact that the majority of the boats hit were LCPs carrying boat group commanders. The Japanese, correctly surmising that the more distinctive LCPs were command craft, directed most of their fire on these boats.

The initial reorganization of the elements of the battalion landing team was handicapped further by the wounding and later evacuation of the battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Leonard M. Mason. Control of boat teams was difficult under the pounding of 90-mm and “knee mortar”7 bursts mixed with the raking fire of machine guns and rifles. Platoons and squads from all companies were mixed along the beach. The original plans directed Company A to land on Cape Torokina, but after the assault waves were dispersed and tangled by the effective fire of the Japanese 75-mm artillery piece, elements of Company C landed on the promontory. Several squads from Company F of the 2nd Battalion also landed in this area and were forced to fight their way along the beach to reach their parent unit. Only Company B of the 1st Battalion landed on its assigned beach. Casualties were fairly light, though, despite the intense fire of the enemy. In addition to at least 14 men lost in the landing craft which had been sunk, fewer than a dozen Marines had been killed on the beach.

The 1st Battalion hesitated only a short time; then the extensive schooling of the past asserted itself. Training in small unit tactics against a fortified position now paid big dividends. Rifle groups began to form under ranking men, and the fight along the shoreline became a number of small battles as the Marines fought to widen their beachhead against the enemy fire. As the Marines became oriented to their location and some semblance of tactical integrity was restored, the pace of the assault quickened.

Before the operation, all units had been thoroughly briefed on the mission of each assaulting element, and each squad, platoon, and company was acquainted with the missions of other units in the area. In addition, each Marine was given a sketch map of the Cape Torokina shoreline. Small groups formed under the leadership and initiative of junior officers and staff noncommissioned officers, and these groups, in turn, were consolidated under one command by other officers. Bunker after bunker began to fall to the coordinated and well-executed attacks of these groups. As the Japanese defensive complex slowly cracked, the 1st Battalion command was established under the battalion executive officer, and the hastily re-formed companies took over the mission of the area in which they found themselves.

The efficient reduction of the enemy’s defensive position added another testimonial to prior training and planning. Officers of the 3rd Marine Division had studied the Japanese system of mutually protecting bunkers on New Georgia and decided that in such a defensive complex the reduction of one bunker would lead to the elimination of another. In effect, one bunker unlocked the entire position. The quickest way to knock out such pillboxes with the fewest casualties to the attacking force was for automatic riflemen to place fire on the embrasures of the bunker while other Marines raced to its blind side to drop grenades down the ventilators or pour automatic rifle fire into the rear entrance.

By midmorning, through such coordinated attacks, most of the Japanese bunkers on Cape Torokina had been knocked out. The position containing the murderous 75-mm gun was eliminated by one Marine who, directing the assault of a rifle group, crept up to the bunker and killed the gun crew and bunker occupants before falling dead of his own wounds. After the last emplacement was silenced late that afternoon, Marines counted 153 dead Japanese in the Cape Torokina area.

For a while, the situation on the right flank had been touch and go. One hour after the landing, a variation of the time-honored Marine Corps phrase was flashed from the Cape Torokina beach. “The situation appears to be in hand,” was the first message, but a few minutes later a more history-conscious officer flashed an amended signal: “Old Glory flies on Torokina cape. Situation well in hand.” The most expressive message, however, to observers on board the transports was the report from a young officer to Colonel McHenry: “... the troops are magnificent.”8 The Marine officers who had directed the assault on the fortified positions added sincere endorsements to this expression of admiration.

On Puruata Island, the 3rd Raider Battalion (Lieutenant Colonel Fred D. Beans) landed with one reinforced company in the assault and the remainder of the battalion as reserve and shore party. Only sporadic fire hit the boats as they neared the island. By 0930, the raiders had established a perimeter about 125 yards inland against hidden snipers and accurate machine gun and mortar fire. The Japanese, obviously outnumbered, gave little indication of yielding, and, by 1330, the reserve platoons of the battalion were committed to the attack. The raiders, with the added support of several self-propelled 75-mm guns attached from the 9th Marines, then moved about halfway across the island.

Puruata was not declared secured until mid-afternoon of the following day. A two-pronged attack, launched by the raiders early on the morning of 2 November, swept over the island against only sporadic rifle fire, and, by 1530, all Japanese resistance on the island had been erased. Only 29 dead enemy were found, although at least 70 were estimated to have been on the island. The remainder had apparently escaped to the mainland. The raiders lost 5 men killed and 32 wounded in the attack.9

Marines wading ashore on D-Day at Bougainville, as seen from a beached LCVP. (USN 80-G-54348)

Puruata island in the foreground, Torokina airfield in the background, appear in an aerial photograph taken on 13 December 1943. (USMC 68047)

The Marines’ fight uncovered extensive enemy defenses which were not disclosed in aerial photographs taken before the operation. The entire headland was ringed by 15 bunkers, 9 of them facing to the west and 6 of them overlooking the beaches on the east side of the cape. Behind this protective line and farther inland was another defensive line of eight bunkers which covered the first line of fortifications. Two other bunkers, about 750 yards inland, provided additional cover to the first two lines.

Constructed of ironwood and coconut logs two feet thick, the bunkers were bulwarked by sandbags and set low into the ground. Camouflaged by sand and tangled underbrush, the bunkers were hard to detect and difficult to knock out without flamethrowers or demolitions. Despite this, the 3rd Marines suffered few casualties in destroying this defensive installation. Twenty of the bunkers had been eliminated by the coordinated fire and maneuver of individual Marines; the remaining five were blasted apart by self-propelled tank destroyers firing 75-mm armor-piercing shells directly into the embrasures.

The enemy 75-mm artillery piece sited as a boat gun hit 14 boats during the initial landings before it was put out of action. Only four of the boats sank. Despite the high velocity of the shells and the slow speed of the landing craft, the 50 or more rounds fired by the enemy scored remarkably few hits. This was attributed to two factors: the poor accuracy of the Japanese gunners and the limited traverse of the gun. Marines found, after knocking out the bunker, that the aperture in the pillbox permitted the muzzle of the gun to be moved only three degrees either way from center. This prohibited the gun from bringing enfilade fire to bear on the beaches. Had this been possible, the large number of boats along the shoreline would have been sitting targets which even poor gunners could not miss, and the casualties to the landing force would have been correspondingly greater.

The unexpected resistance on Cape Torokina and Puruata island after the naval gunfire bombardment and bombing was a sharp disappointment to IMAC officers who had requested much more extensive preparatory fires. The gunfire plan, which was intended to knock out or stun enemy defenses that might delay the landing, had accomplished nothing. The Anthony, firing on Puruata Island, reported that its target had been well covered; but the raider battalion, which had to dig the defenders out of the emplacements on the island, reported that few enemy installations had been damaged.

The Wadsworth and Sigourney, firing at ranges opening at 11,000 to 13,000 yards, had difficulty hitting the area and many shots fell short of the intended targets. The Terry, closest to the shore but firing at an angle into the northwestern face of Cape Torokina, was poorly positioned for effective work. None of the 25 bunkers facing the landing teams on the right had been knocked out by gunfire, and only a few of the Japanese huts and buildings inland were blasted by the ships’ fire. The gunnery performance of the destroyers left much to be desired, IIIPhibFor admitted later. Particularly criticized was the fact that some ships fired short for almost five minutes with all salvos hitting the water. After two or three rounds, the range should have been adjusted, but apparently the practice bombardment at Efate had not been sufficient.

The long-range sniping at Cape Torokina with inconclusive results was vindication for the IMAC requests prior to the operation that the destroyers move as close to the shoreline as possible for direct fire.

The sad thing about the whole show, to the corps and division gunfire planners, was that the means actually were available to give us just what we wanted, but were dissipated elsewhere in what we felt was fruitless cannonading.10

Valuable lessons in gunfire support were learned at Bougainville that D-Day. For one thing, the line of flat trajectory fire in some places passed through a fringe of tall palm trees which exploded the shells prematurely and denied direct observation of the target area. Further, the ships had trouble seeing the shoreline through the combination of early morning haze and the smoke and dust of exploding shells and bombs, rising against a mountainous background.

Although the enemy airfields in the Bougainville area were knocked out by Admiral Merrill’s final bombardment and the prior action of ComAirSols bombing strikes, the Japanese reaction to the landing came swiftly. At 0718, less than two hours after the transports appeared off Cape Torokina and about eight minutes before the first assault boats hit the beach, a large flight of Japanese planes was detected winging toward Empress Augusta Bay. The transports, most of them trailing embarkation nets, immediately pulled out of the bay toward the sea to take evasive action again.

The first enemy flight of about 30 planes, evidently fighters from the naval carrier groups land-based in New Britain, was intercepted at about 0800 by a New Zealand fighter squadron flying cover over the beachhead. Seven of the Japanese planes were knocked down, but not before a few enemy raiders strafed the beaches and dive-bombed the frantically maneuvering APAs and AKAs. Ten minutes later, another flight of enemy fighters and bombers struck the area in a determined attack, but were turned away by the fierce interference of other ComAirSols planes, including Marine fighters from VMF-215 and VMF-221. Radical evasive tactics by the transports—aided by excellent antiaircraft gunnery by the destroyer screen and savage pursuit by the fighter cover—prevented the loss of any ships, although the Wadsworth took some casualties from a near miss. The fighter cover downed eight planes, and the destroyer screen claimed another four raiders.

Two hours after the attack began, the APAs and AKAs returned to resume operations. Valuable time, however, had been lost. Intruding enemy planes continued to harass the transports, but unloading operations kept up until about 1300, when the arrival of another large formation of about 70 enemy planes put the ships into action again.

One APA, the American Legion, grounded on a shoal and remained there during the attack despite the persistent efforts of two tugs which attempted to free it. A destroyer resolutely stood guard, pumping antiaircraft fire into attacking planes. The ship was pulled free before the air attack was driven off. As before, the aggressive fighter cover and heavy fire from the destroyer screen prevented damage to the amphibious force, and the ships turned back to the task of unloading. During the attacks, the Allies claimed 26 enemy planes as shot down—four more

than the Japanese records indicate—with the loss of four planes and one pilot. For the first day, at least, the threat of enemy air retaliation had been turned back.

Establishing a Beachhead11

Ashore, the defensive perimeter now stretched a long, irregular semi-circle over the area from the Laruma River past Cape Torokina, a distance of about four miles. Only the northern beaches were quiet; the area around the cape was still being contested by snipers within this perimeter and by small groups of enemy in the jungle outside the line. Within this area, the logistics situation was beginning to be cause for concern.

Confusion began after wrecked tank lighters and personnel boats were broken on the northern beaches, closing those areas to further traffic. When unloading operations began once more after the first air raid, the northern beaches were ordered abandoned and all cargo destined for the 9th Marines sector was diverted to beaches south of the Koromokina River. This change, the only move possible in view of the difficult surf conditions, led to further complications because the beaches in the 3rd Marines’ sector were already crowded, and the coxswains on the landing craft had no instructions regarding where the supplies should be dumped.

The landing beaches in the 3rd Marines’ sector were hardly an improvement. Few had any depth, and from the outset it was apparent that the swampy jungle would stall operations past the beaches. The only means of movement was laterally along the thin beach, and the gear already stacked along the shoreline was causing congestion along this route. The difficult terrain inland made the formation of dumps impractical, so all cargo was placed above the high water mark and some degree of orderliness attempted. Despite this, the 9th Marines lost much organizational property and supplies, most of which was never recovered.

As cargo and supplies mounted on the beaches assigned to the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 3rd Marines, the bulk cargo was diverted further to Puruata Island. The landing craft were unloaded within a few hundred yards of the battle between the raiders and the small but determined group of defenders emplaced there. Almost 30 percent of the total cargo carried by the 12 transports was unloaded by 1130 of D-Day, and this figure was extended to almost 50 percent completion by the time that the APAs and AKAs had to depart the area for the second time. The cargo remaining on board was varied; some ships had unloaded all rations but little ammunition. Other transports had unloaded ammunition first and were just starting to move the other supplies.

While the combat troops ashore prepared to defend the newly won beachhead,

the transport groups proceeded to unload as rapidly as the air attacks, loss of boats, and elimination of a number of beaches would permit. By 1600 on D-Day, only the four northernmost transports—the ones most affected by the boat mishaps and the unsuitable beaches—still had cargo on board.

The quick unloading of the other five APAs and three AKAs, despite the interruptions, was a reflection of the measures taken by Admiral Wilkinson and General Vandegrift to insure rapid movement of supplies ashore. Embarked troops on each APA and AKA had been required to furnish a complete shore party of about 500 men. During the unloading, 6 officers and 120 men remained on board ship to act as cargo handlers while a further 60 were boat riders to direct the supplies to the proper beaches. Another 200 Marines stayed on each beach to help unload the landing craft. The remaining personnel were used as beach guides, vehicle drivers, cargo handlers, and supervisors.12 The 3rd Service Battalion, augmented by supporting troops—artillerymen, engineers, military police, signal men, tank men, communicators, and Seabees—formed the bulk of these working parties. In some instances, these supporting troops were not released to their units until several days after the beachhead had been established. In all, about 40 percent of the entire landing force was engaged initially in shore party activities.

By late afternoon, each landing team reported its mission accomplished. In the absence of any identifiable terrain features in the interior, the landing teams had been directed to extend the beachhead certain distances, and, by the end of D-Day, each of the battalions was established in a rough perimeter along the first of these designated Inland Defense Lines. The division front lines extended into the jungle about 600 yards near the Laruma River and about 1,000 yards in front of Cape Torokina. Although the 1st Battalion, 3rd Marines, in the area of the cape plantation, and the 3rd Raiders on Puruata Island were still receiving occasional sniper fire, the remainder of the perimeter was quiet and defense was not a special problem.

There was, however, still congestion on the shoreline. In order to bring some order out of the near chaos on the beaches and to reduce the paralyzing effect of the mountains of supply piled helter-skelter, additional Marines from the combat forces were detailed as labor gangs to sort the supplies and haul them to the front-line units. This placed a double-burden on some units who were already near half-strength by the assignment of troops to the shore party work.

An additional problem, late on D-Day, was the correlation and coordination of the defensive positions and missions of the many assorted and unrelated supporting units which had landed during the day. These included echelons of artillery, antiaircraft artillery, and seacoast defense units. The 12th Marines, decentralized with a battery attached to each landing team, was in varying stages of readiness for defense of the beachhead. Battery B, in the 9th Marines area, was in position by early afternoon but was so engaged in cargo hauling that the first requests for a firing mission could not be completed. Other batteries were also in position by the end of D-Day, and several had fired registration shots and were available for intermittent fires during the first night.

The remaining batteries were ready for support missions the following day.

Selection of positions in most areas was difficult. The battery supporting the 2nd Raider Battalion was forced to move inland about 100 yards through a lagoon before a position could be located. Two amphibian tractors ferried the guns and most of the ammunition across the water, and the artillerymen transferred the remaining ammunition from the beach to the gun position by rubber boats. This battery registered on Piva Village by air spot, and the next day fired 124 rounds on suspected enemy positions in the vicinity of that village.

Antiaircraft batteries (90-mm) and the Special Weapons Group of the 3rd Defense Battalion landed right behind the assault units. Advance details of the seacoast defense battery also moved ashore early and immediately began seeking suitable positions to mount the big guns. After the first air raid on the morning of D-Day, the remaining antiaircraft guns of the Marine defense battalion were hurried ashore so that protection of the beachhead could be increased as soon as possible. By nightfall of D-Day, 20 40-mm guns, 8 20-mm guns, and the .50 and .30 caliber machine guns of the battalion were integrated into the defense of the perimeter and were ready for action.

As nightfall approached, the frontline units sited all weapons along fixed lines to coordinate their fire with adjacent units, and all companies set up an all-around defense. Supporting units on the beach also established small perimeters within this defensive line. There was to be no unnecessary firing and no movement. Marines were to resort to bayonets and knives when needed, and any Japanese infiltrators were to be left unchallenged and then eliminated at daybreak. An open-wire telephone watch was kept by all units, and radios were set to receive messages but no generators were started for transmissions.

The night passed as expected—Marines huddling three to a foxhole with one man awake at all times. A dispiriting drizzle, which began late on D-Day afternoon, continued through the night. Japanese infiltrators were busy, and several brief skirmishes occurred. An attack on a casualty clearing station was repulsed by gunfire from corpsmen and wounded Marines; and one battalion command post, directly behind the front lines, was hit by an enemy patrol. The attackers were turned back by the battalion commander, executive officer, and the battalion surgeon who wielded knives to defend their foxhole.

While the Marines ashore had busied themselves getting ready for the first night of defense of the beachhead, the transport groups proceeded with the unloading details. At 1645, the transports were advised to debark all weapons, boat pool personnel, and cargo handlers and leave the area at 1700. The four transports still with supplies aboard (the Alchiba, American Legion, Hunter Liggett, and the Crescent City) were to keep working until the final moment and then leave with the rest of the transports despite any Marine working parties still on board.

Admiral Wilkinson, aware that the situation ashore was well under control, had decided that all ships would retire for the night and return the next day. In event of a night attack, the transports in Empress Augusta Bay would be sitting ducks. The admiral felt that his ships could not maneuver in uncharted waters at night, and that night unloading operations were not feasible. The admiral had another reason, too. An enemy task force of four

cruisers and six destroyers was reported heading toward Rabaul from Truk, and these ships, after one refueling stop, could be expected near Bougainville later that evening or early the next morning. The amphibious force, as directed, moved out to sea for more protection.

At 2300 that night, 1 November, the four transports which were still to be unloaded were ordered to reverse course and head back toward Empress Augusta Bay while the rest of the transports continued toward Guadalcanal. The four transports, screened by destroyers, regulated their speed and direction so as to reach the Cape Torokina area after daybreak. A short time later, alerted to the fact that a large enemy fleet was in the area, the transports headed back toward Guadalcanal again.

Admiral Merrill’s Task Force 39, after the successful bombardment of Buka and the Shortlands which opened the Bougainville operation, had moved north of Vella Lavella to cover the retirement of the transport group. At this particular time, Merrill’s concern was the condition of his force which had been underway for 29 hours, steaming about 766 miles at near-maximum speed. Although the cruisers were still able to fight, the fuel oil supply in the destroyers was below the level required for anything but small engagements at moderate speeds.

So, while Merrill’s cruisers waited, one of the two destroyer divisions in the task force turned and headed for New Georgia to refuel. That afternoon, 1 November, while an oil barge was pumping oil into the destroyers at maximum rate, the report of the Japanese fleet bearing down on Bougainville was received. The destroyers, impatient to get going, hurried through the refueling.

At 1800, all destroyers raced out of Kula Gulf to rejoin Merrill. The 108-mile trip was made at 32 knots, although the engines of two of the destroyers were on the verge of breakdown. By 2330, the ships joined Merrill’s cruisers south of the Treasurys, and the entire task force headed toward Bougainville where it interposed itself between the departing transports and the oncoming enemy fleet. Allied patrol planes had kept the attack force under surveillance all day, and, by nightfall, the direction of the Japanese ships was well established. If the Allied thinking was correct, another trap had been baited for the Japanese. The enemy, guessing that the same task force that hit Buka had provided the shore bombardment for the Cape Torokina landing, might be lured into assuming that the fighting ships were now low on fuel and ammunition and had retired with the transports. If that was the enemy assumption, then Merrill was in position for a successful ambush.

Moving slowly to leave scant wake for enemy snooper planes to detect, Merrill’s force was off Bougainville by 0100, 2 November, and beginning to maneuver into position to intercept the enemy fleet. At that time, the enemy was about 83 miles distant. Merrill’s basic plan was to stop the enemy at all costs, striking the Japanese ships from the east so that the sea engagement would be deflected toward the west, away from Bougainville. This would give his ships more room to maneuver as well as allow any damaged ships to retire to the east on the disengaged side. Further, Merrill respected the Japanese torpedoes and felt that his best chance to divert the enemy force and turn it back—possibly without loss to his own

force—was by long-range, radar-directed gunfire.

The naval battle of Empress Augusta Bay began just 45 miles offshore from the beachhead whose safety depended upon Task Force 39. Merrill’s cruisers opened fire at 0250 at ranges of 16,000 to 20,000 yards. The enemy fleet, spread out over a distance of eight miles, appeared to be in three columns with a light cruiser and destroyers in each of the northern and southern groups and two heavy cruisers and two destroyers in the center. Detection was difficult because, with the enemy so spread out, the radar on Merrill’s ships could not cover the entire force at one time.

The enemy’s northern force was hit first, the van destroyers of Task Force 39 engaging this section while the rest of the American ships turned toward the center and southern groups. As planned, the attack struck from the east. Task Force 39 scored hits immediately, drawing short and inaccurate salvos in return. The Japanese, relying on optical control of gunfire, lighted the skies with starshells and airplane flares; but this also helped Task Force 39, since the enemy’s flashless powder made visual detection of the Japanese ships almost impossible without light.

The two forces groped for each other with torpedoes and gunfire. In the dark night, coordination of units was difficult and identification of ships impossible. The maneuvering of Merrill’s task units for firing positions, as well as the frantic scattering of the enemy force, spread the battle over a wide area, which further increased problems of control and identification. On at least one occasion, Task Force 39 ships opened fire on each other before discovering their error.

In such confused circumstances, estimation of damage to either force was almost impossible, although some of the American destroyers believed that their torpedoes had found Japanese targets, and other enemy ships were believed to have been hit by gunfire. In the scramble for positions to take new targets under fire, two destroyers of Merrill’s force scraped past each other with some damage, and several other close collisions between other destroyers were narrowly averted. One American destroyer, the Foote, reported itself disabled by an enemy torpedo and two other destroyers were hit by gunfire but remained in action. The only cruiser damaged was the Denver, which took three 8-inch shells and was forced to disengage for a short time before returning to the fight.

By 0332, Task Force 39 was plainly in possession of the field. The enemy force, routed in all directions, had ceased firing and was retiring at high speed. Merrill’s cruiser division ceased firing at 0349 on one last target at ranges over 23,000 yards. This ended the main battle, although the TF 39 destroyers continued to scout the area for additional targets and disabled enemy ships. At daybreak, TF 39 was reassembled and a flight of friendly aircraft appeared to provide escort for its retirement. The Foote was taken under tow and the return to Guadalcanal started. The Merrill force believed that it had sunk at least one enemy light cruiser and one destroyer and inflicted damage on a number of other ships. This estimate was later found correct.13 In addition, the

Japanese also had several ships damaged in collisions.

Task Force 39 was struck a few hours later by a furious air attack from more than 70 enemy planes, but the Japanese made a mistake in heading for the cruisers instead of the destroyers guarding the disabled Foote. The heavy antiaircraft fire and the aggressive protection of the ComAirSols fighter cover forced the enemy planes away. The air cover shot down 10 planes, and the ships reported 7 enemy aircraft downed. Only one American cruiser, the Montpelier, was hit by bombs but it was able to continue. While the air battle raged, the amphibious force’s transports reversed course once more and returned to Cape Torokina without interference and completed the unloading. The sea and air offensive by the Japanese had been stopped cold by the combined action of ComSoPac’s air and sea forces.

The Japanese14

To the Japanese defenders, the sudden appearance of a number of transports off Cape Torokina on the morning of 1 November came as something of a shock. All Japanese plans for the island had discounted a landing north of Cape Torokina because of the nature of the beaches and the terrain. If the Allies attacked the western coast of Bougainville, the enemy thought the logical place would be southern Empress Augusta Bay around Cape Mutupena. Japanese defensive installations, of a limited nature, were positioned to repel an Allied landing in this area.

But the small garrison in the vicinity of Cape Torokina, about 270 men from the 2nd Company, 23rd Regiment, with a regimental weapons platoon attached, was well trained. From the time that the alarm was sounded shortly after dawn on 1 November, the Japanese soldiers took up their defensive positions around the cape and prepared to make the invading forces pay as dearly as possible for a beachhead.

The invading Marines found the island’s defenders dressed in spotless, well-pressed uniforms with rank marks and service ribbons, an indication that the Cape Torokina garrison was a disciplined, trained force with high morale, willing to fight to the death to defend its area. But after the first day, when the Japanese were knocked out of the concentrated defenses on Cape Torokina, the enemy resistance was almost negligible. A wounded Japanese sergeant major, captured by Marines the second day, reported that the understrength garrison had been wiped almost out of existence. The prisoner confirmed that the Japanese had expected an attack on Bougainville for about three days—but not at Cape Torokina.

With the notice of the Allied operations against Bougainville, all available Japanese air power was rushed toward Rabaul, and Admiral Kusaka ordered the interception operations of the Southeast Area Fleet (the Ro operation) shifted from New Guinea to the Solomons. Because all planes of the 1st Air Squadron and additional ships were already en route to Rabaul, this action placed the entire mobile surface and air strength of the Combined Fleet under the direction of the commander of the Southeast Area Fleet.

The protests of some commanders against the use of surface vessels in the area south of New Britain—which was well within the range of the area dominated by the planes of ComAirSols—were brushed aside. Combined Fleet Headquarters, convinced that this was the last opportunity to take advantage of the strategic situation in the southeast, was determined to strike a decisive blow at the Allied surface strength in the Solomons and directed Kusaka to continue the operation.

After the battle of Empress Augusta Bay, however, the defeated Japanese retired from the area with the realization that combined sea and air operations were difficult with limited air resources, especially “in a region where friendly and enemy aerial supremacy spheres overlapped broadly.”15

The Seventeenth Army, charged with the actual defense of Bougainville, took the news of the Allied invasion a bit more blandly:

In formulating its operation plan, the Seventeenth Army planned to employ its main force only on the occasion of an army invasion in the southern or northern region, or the Kieta sector. Therefore, at the outset of the enemy landing in the vicinity of Torokina Point, the Seventeenth Army was lacking in determination to destroy the enemy. The army’s intention at that point was only to obstruct the enemy landing.16

There were many avenues of obstruction open to the Japanese, despite the fact that the Allied sea and air activity probably discouraged the enemy from many aggressive overtures. Deceived originally as to the intentions of the Allies, the Japanese apparently remained in doubt for some time as to the strategical and tactical importance of the operations at Cape Torokina. The enemy could have counter-landed or prevented extension of the defensive positions and occupation of the projected airfield sites by shelling or air bombardments. But none of these courses of action were initiated immediately or carried out with sufficient determination to jeopardize the beachhead seized by the IMAC forces.

The chief threat to the Cape Torokina perimeter seemed to be from the right flank. Operation orders, taken from the bodies of dead Japanese at Cape Torokina, indicated that forces in the area southeast of the Cape could strike from that direction, and it was to this side that the IMAC forces ashore pointed most of their combat strength.