Chapter 4: Holding the Beachhead

Expansion of the Perimeter1

The landings on Bougainville had proceeded as planned, except that the 3rd Marines encountered unexpectedly stiff resistance initially and the 9th Marines landed over surf and beaches which were later described as being as rough as any encountered in the South Pacific. The success of the operation, though, was obvious, and General Vandegrift, leaving Turnage in tactical control of all IMAC troops ashore, confidently returned to Guadalcanal with Wilkinson.2

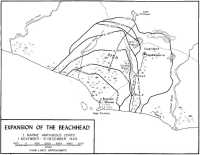

At daybreak the second day, the Marines began expansion of the beachhead. Flank patrols along the entire perimeter established a cohesive defensive front, and from this position a number of reconnaissance patrols were pushed forward. There was no enemy activity except occasional sniper fire in the vicinity of Torokina plantation and on Puruata Island, where the raiders were still engaged.

Patrols had to thread their way through a maze of swamps that stood just back of the beaches, particularly in the 3rd Marines’ zone of action. Brackish water, much of it knee to waist deep, flooded inland for hundreds of yards. The bottom of these swamps was a fine, volcanic ash which had a quicksand substance to it. Marines had trouble wading these areas, and bulldozers and half-tracks all but disappeared under the water.3

Only two paths led out of this morass, both of them in the sector of the 3rd Marines. These two trails, in some places only inches above the swampland, extended inland about 750 yards before joining firmer ground. One of the pathways, the Mission Trail toward the Piva River and Piva Village, was believed to be the main route of travel by the Japanese forces, and this trail was blocked on D-Day by the quick action of raider Company M. More detailed information on the extent of swamps and the location of higher ground would have been invaluable at this stage of beachhead expansion, but the aerial photographs and hasty terrain maps available furnished few clues

as to suitable locations for defensive positions or supply dumps. The result was complete dependence upon reports of the reconnaissance patrols.4

Because the routes inland were passable only to tracked vehicles, road building became the priority activity of the operation. Wheeled vehicles and half-tracks could be used only along the beaches, and in places where the shoreline was only a few yards wide, the supplies piled around had a paralyzing effect on traffic. The 53rd and 71st Seabees, which landed in various echelons with the assault troops, began construction of a lateral road along the beach while waiting for the beachhead to expand.

Construction of a similar road along the Mission Trail was handicapped by the swamps and the lack of bridging material. Progress was slow. Airfield reconnaissance on Cape Torokina was begun at daybreak despite the sporadic sniper fire, but plans for immediate patrols to seek airfield sites further inland was postponed by the need for roads and the limited beachhead.

Early on the morning of 2 November, a shift in the tactical lineup along the perimeter was ordered in an attempt to pull in the flanks of the beachhead and constitute a reserve force for IMAC. Prior to the operation, General Turnage had been concerned about the possibility of his lengthy but narrow beachhead being rolled up like a rug by enemy action. Without a reserve and unable to organize a defense in depth to either flank, the division commander had planned to move individual battalions laterally to meet enemy threats as they developed. Now, with the beaches in the 9th Marines’ sector unsuitable for continued use, and the 3rd Marines needing some relief after the tough battle to take Cape Torokina, redisposition of certain units was directed.5

At 0830, the 2nd Battalion, 9th Marines started drawing in its left flank toward the beach while 1/9, the extreme left flank landing team, began withdrawal to the vicinity of Cape Torokina. Some units moved along the beach; others were lifted by amphibian tractors. By nightfall, 1/9 was under the operational control of the 3rd Marines and was in reserve positions behind 1/3 on the right flank. Two artillery batteries of the 12th Marines registered fire on the Laruma River to provide support for 2/9 on the left flank.

The following day, 3 November, 2/9 made the same withdrawal and moved into positions to the right of the 2nd Raider Battalion. During the day, 1/9 relieved 1/3 on the right flank of the perimeter, and at 1800 operational control of Cape Torokina passed to the 9th Marines. At this time, 3/9 with its left flank anchored to the beach north of the Koromokina River, was placed under the control of the 3rd Marines; 1/3, withdrawn from action, was designated the reserve unit of the

Map 15: Expansion of the Beachhead, I Marine Amphibious Corps, 1 November-15 December 1943

9th Marines. In effect, after three days, the two assault regiments had traded positions on the perimeter and had exchanged one battalion.

The last Japanese resistance within the perimeter had been eliminated, also. On 3 November, after several instances of sporadic rifle fire from Torokina Island, the artillery pieces of a battery from the 12th Marines, as well as 40-mm and 20-mm guns of the 3rd Defense Battalion, were turned on Torokina Island for a 15-minute bombardment. A small detachment of the 3rd Raiders landed behind this shelling found no live Japanese but 8-10 freshly dug graves. The enemy had apparently been forced to abandon the island.

Extension of the perimeter continued despite the shuffling of front-line units. On the left, 3/9 and the two battalions of the 3rd Marines continued to press inland in a course of advance generally north by northeast. Contact was maintained with the 2nd Raider Battalion on the right of the 3rd Marines, and patrols scouted ahead with the mission of locating the route for a lateral road from the left flank to the right flank. The 2nd Raiders, moving along the Mission Trail in front of the 9th Marines, extended the beachhead almost 1,500 yards. In this respect, the addition of a war dog platoon to the front-line units was invaluable. Not only did the alert Doberman Pinschers and German Shepherds smell out hidden Japanese, but their presence with the patrols gave confidence to the Marines.

On 4 November, extensive patrolling beyond the perimeter north to the Laruma River and south to the Torokina River was ordered, but enemy contact was light and only occasional sniper fire was encountered. The 1/9 patrol to the Torokina River killed one sniper near the Piva, and some enemy activity was reported in front of 2/9; other than that, enemy resistance had vanished.

By the end of the following day, 5 November, the IMAC beachhead extended about 10,000 yards along the beach around Cape Torokina and about 5,000 yards inland. Defending along the perimeter were five battalions (3/9, 3/3, 2/3, 2/9, and 1/9) with 1/3 in reserve. The 2nd Raiders, leaving one company blocking Mission Trail, and the 3rd Raiders were assembled under control of the 2nd Raider Regiment commander, Lieutenant Colonel Alan Shapley, in IMAC reserve on Puruata Island and Cape Torokina.

All other IMAC units which had been engaged in shore party operations also reverted to parent control. By this time, two battalions of the 12th Marines were in position to provide artillery support to the beachhead and the antiaircraft batteries of the 3rd Defense Battalion were operating with radar direction. With all units now able to make a muster of personnel, the IMAC casualties for the initial landings and widening of the beachhead were set at 39 killed and 104 wounded. Another 39 Marines were reported missing. The Japanese dead totaled 202.

Nearly 6,200 tons of supplies and equipment had been carried to Empress Augusta Bay by the IIIPhibFor transports. By the end of D-Day, more than 90 percent of this cargo was stacked along the beaches in varying stages of organization and orderliness. The problem was complicated further by the final unloading of the four transports on D plus 1. Practically every foot of dry area not already occupied by troop bivouacs or gun emplacements was piled high with cargo, and the troops still serving as the shore party were hard-pressed to find additional

storage areas within the narrow perimeter. Ammunition and fuel dumps had to be fitted in temporarily with other supply dumps, and these in turn were situated where terrain permitted. The result was a series of dumps with explosives and fuels dangerously close to each other and to troop areas and beach defense installations.

Main source of trouble was the lack of beach exits. Some use of the two trails had been attempted, but these had broken down quickly under the continual drizzle of rain and the churning of tracked vehicles. The lateral road along the beach was practically impassable at high tide, and at all times trucks were forced to operate in sea water several inches to several feet deep. Seabees and engineers, attempting to corduroy some of the worst stretches, had their efforts washed out.

The bordering swamplands, which restricted the use of wheeled vehicles and half-tracks in most instances, forced the discovery of the amphibian tractor as the most versatile and valuable addition to the landing force. Already these lumbering land-sea vehicles had proven their worth in carrying cargo, ferrying guns, and evacuating wounded men through the marsh lands and the lagoons, and the variations of their capabilities under such extreme circumstances were just beginning to be realized and appreciated. The arrival of the LST echelons later brought more of these welcome machines to the beachhead.

IMAC and 3rd Marine Division engineers landed in the first echelons on D-Day, but reconnaissance to seek supply routes into the interior and supply dump locations was handicapped by the limited expansion of the beachhead. Many survey missions bumped into the combat battalions and were discouraged from patrolling in front of the defensive positions by the Marines who preferred to have no one in advance of the lines except Japanese. This problem was solved by the frontline units furnishing combat patrols for engineer survey parties who moved ahead and then worked a survey back to the old positions.

The swamplands were successfully attacked by a series of drainage ditches into the sea. As the ground dried, the volcanic ash was spread back as fill dirt. The airfield work was slowed by the many supply dumps and gun emplacements which had been placed in the vicinity of the plantation, one of the few dry spaces around. Many division dumps and artillery positions had to be moved from the area, including one battery of 90-mm guns of the 3rd Defense Battalion which occupied a position in the middle of the projected runway.

By the time the first supporting echelon of troops and cargo arrived on 6 November, the Torokina beachhead was still handicapped by the lack of good beach facilities and roads. Airfield construction had slowed the development of roads, and vice versa, and the loose sand and heavy surf action along the Cape Torokina beaches resisted efforts to construct proper docking facilities for the expected arrival of the supporting echelons.6 Coconut log ramps, lashed together by cables, were extended about 30 feet from the shoreline, but these required constant rebuilding. Later, sections of bridges were used and these proved adaptable to beach use.

The reinforcements arrived at Torokina early on the morning of 6 November. The

3,548 men and 6,080 tons of cargo were embarked at Guadalcanal on the 4th on eight LSTs and eight APDs, which were escorted to Cape Torokina by six destroyers. The APDs unloaded a battalion landing team from the 21st Marines and other division elements quickly and then headed back to Guadalcanal for another echelon. But the unloading of the LSTs was slowed by the crowded conditions of the main beaches and the lack of beach facilities. Most of the cargo was unloaded at Puruata Island where the tank landing ships could beach adequately, and the cargo was then transshipped to the mainland.7 This created something of a problem, too, for supplies were poured onto Puruata without a shore party to organize the cargo; and this condition was barely cleared up before another echelon of troops and supplies arrived.

Counterlanding at Koromokina8

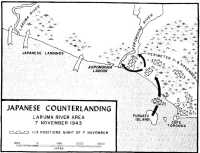

After the first desperate defense of Cape Torokina, the enemy had offered no resistance. Then, on 7 November, the Japanese suddenly launched a counterlanding against the left flank of the beachhead. The move caught the 3rd Marine Division in the midst of reorganization of the perimeter to meet the expected threat on the right flank.

The counterlanding fulfilled an ambition long cherished by the Japanese. At Rendova, an attempted landing against the Allied invasion forces fizzled out during a downpour that prevented the rendezvous of the Japanese assault force; and at New Georgia, the enemy considered—then rejected—an idea to land behind the 43rd Division on Zanana Beach. The Cape Torokina operation, however, gave the Japanese a chance to try this favored counterstroke. Such a maneuver was in line with the basic policy of defense of Bougainville by mobile striking forces, and, in fact, a provisional battalion was in readiness at Rabaul for just such a counterlanding attempt.

This raiding unit was actually a miscellany of troops from several regiments of the 17th Division. Specially trained, the battalion included the 5th Company, 54th Infantry; the 6th Company, 53rd Infantry; a platoon from the 7th Company, 54th Infantry; and a machine gun company from the 54th Infantry, plus some service troops. Japanese records place the strength of the battalion at about 850 men.9

The attack force started for Cape Torokina on the night of 1 November, but the reported presence of an Allied surface fleet of battleships and cruisers in the area, and the threat of being discovered by Allied planes, convinced the Japanese that a counterlanding at this time would be difficult. Accordingly, the attempt was postponed, and the troops returned to Rabaul while Admiral Kusaka’s Southeast Area Fleet concentrated on destroying the Allied interference before another try was made. The landing party finally departed Rabaul on 6 November, the four troop

Calf-deep mud clings to a column of Marine ammunition carriers as they move toward the front lines on Bougainville. (USMC 68247)

Admiral Halsey and General Geiger watch Army reinforcements file along the shore at Bougainville. (USMC 65494)

destroyers screened by a cruiser and eight escort destroyers.

Shortly after midnight, the transport group entered the objective area, but the first landing attempt was hurriedly abandoned when Allied ships were discovered blocking the way. The destroyers headed north again, then back-tracked closer to the shoreline for a second try. This time the troop destroyers managed to unload the troops about two miles from the beaches. The landing force demanded protective gunfire from the destroyers, but the Japanese skippers, considering the Allied fleet nearby, paid little heed. The troops, loaded in 21 ramp boats, cutters, and motor boats,10 were landed at dawn near the Laruma River, just outside the left limits of the IMAC perimeter.

First indication that a Japanese counterlanding was in progress came from one of the ships at anchor which reported sighting what appeared to be a Japanese barge about four miles north of Cape Torokina.11 Before a PT boat could race out to check this report, 3rd Marine Division troops on that flank of the beachhead confirmed the fact that enemy barges were landing troops at scattered points along the shoreline and that the Marines were engaging them.

The first landings were made without opposition. A Marine antitank platoon, sited in defensive positions along the beach, did not open fire immediately because of confusion as to the identity of the landing craft. The Marines who witnessed the landings said that the Japanese ramp boats looked exactly similar to American boats, including numbers in white paint on the bow.12 In the early dawn mist, such resemblance in silhouette was enough to allay the suspicions of the sentries. Once the alarm was sounded, artillery pieces of the 12th Marines and coast defense guns—including the 90-mm antiaircraft batteries—of the 3rd Defense Battalion were turned on the enemy barges and landing beaches.13

Instead of landing as a cohesive unit, however, the Japanese raiding force found itself scattered over a wide area, a victim of the darkness and the same surf troubles that earlier had plagued the Marines. Troops were distributed on either side of the Laruma and were unable to reassemble quickly. The Japanese were faced with the problem of attacking with the forces on hand or waiting to reorganize into tactical units. Under fire already, deciding that further delay would be useless, the enemy began the counterattack almost at once. Less than 100 enemy soldiers made the first assault.

The 3rd Battalion, 9th Marines (Lieutenant Colonel Walter Asmuth, Jr.)—occupying the left-flank positions while waiting to be moved to the Cape Torokina area—drew the assignment of stopping the enemy counterthrust. Artillery support fire was placed in front of the perimeter and along the beach. At 0820, Company K, 3/9, with a platoon from regimental weapons company attached, moved forward to blunt the Japanese counterattack. About 150 yards from the main line of resistance (MLR), the advancing Marines hit the front of the enemy force. The Japanese, seeking cover from the artillery fire, had dug in rapidly and, by taking

Map 16: Japanese Counter-landing, Laruma River Area, 7 November 1943

advantage of abandoned foxholes and emplacements of the departed 1/9 and 2/9, had established a hasty but effective defensive position.

Heavy fighting broke out immediately, the Japanese firing light machine guns from well-concealed fortifications covered by automatic rifle fire from tree snipers. Against this blaze of fire, the Marine company’s attack stalled. The left platoon was pinned down almost at once, and, when the right and center platoons tried to envelop the defensive positions, the dense jungle and enemy fire stopped their advance. The Japanese resistance increased as reinforcements from the remainder of the counter-landing force began to arrive. At 1315, the 1st Battalion of the 3rd Marines in reserve positions in the left sector was ordered into the fight.

While Company K held the Japanese engaged, Company B of 1/3 moved across the MLR on the left flank and passed through Company K to take up the fight. At the same time, Company C of 1/3 moved forward on the right. The 9th Marines’ company withdrew to the MLR leaving the battle to 1/3, now commanded by Major John P. Brody. In the five hours that Company K resisted the Japanese counter-landing, it lost 5 killed and 13 wounded, 2 of whom later died.

The two companies of 1/3 found the going no easier. The Japanese were

well-hidden, with a high proportion of machine guns and automatic weapons, and the Marine attack was met shot for shot and grenade for grenade. In some instances, Marines knocked out machine gun emplacements that were almost invisible in the thick jungle at distances greater than five yards. Tanks moved up to help with the assault, and the Marine advance inched along as the 37-mm canister shells stripped foliage from the enemy positions. High explosive shells, fired nearly point blank, erased many of the enemy emplacements, and in some cases the HE shells—striking ironwood trees—knocked enemy snipers out of the branches.

Late in the afternoon, the advance was halted and a heavy artillery concentration, in preparation for a full-scale attack by the 1st Battalion, 21st Marines, was placed on enemy defenses in front of the Marines. The artillery fire raged through the enemy positions; and to keep the Japanese from seeking cover and safety in the area between the artillery fire and the Marine lines, Companies B and C placed mortar fire almost on top of their own positions.

The attack by 1/21 (Lieutenant Colonel Ernest W. Fry, Jr.) was set for 1700 on the 7th, but the effective artillery-mortar fire and the approaching darkness postponed the attack until the following morning. Fry’s battalion, which landed on Puruata the previous day, was moved to the mainland to be available for such reserve work after the Japanese struck. The battalion spent the night behind the 1/3 perimeter, which, by the end of 7 November, was several hundred yards past the original perimeter position of 3/9 that morning.

The enemy’s action in landing at scattered points along the shoreline resulted in several Marine units being cut off from the main forces during the day. One platoon from Company K, 3/9, scouting the upper Laruma River region, ambushed a pursuing Japanese patrol several times before escaping into the interior. This platoon returned to the main lines about 30 hours later with one man wounded and one man missing after inflicting a number of casualties on the enemy landing force. Another outpost patrol from Company M, 3/9, was cut off on the beach between two enemy forces. Unfortunately, the radio of the artillery officer with the patrol did not function, and so support could not be summoned.

The artillery officer found his way back to the main lines where he directed an artillery mission that landed perfectly on the Japanese position to the left. The patrol then moved toward the division main lines, only to find the beach blocked by enemy forces opposing Company K. A message scratched on the beach14 called an air spotter’s attention to the patrol’s plight, and, late that afternoon, two tank lighters dashed in to the beach to pick up the patrol. Sixty men were evacuated successfully after killing an estimated 35 Japanese. Only two of the Marines had been wounded.

Two other Marine groups became isolated in the fighting along the perimeter. One platoon from 1/3, scouting the enemy’s flank position, slipped through the jungle and passed by the enemy force without being observed. Choosing to head for the beach instead of the interior, the platoon struggled to the coast. There the patrol cleaned its weapons with gasoline from a wrecked barge, and spent the night in the jungle. The next morning, the attention of an Allied plane was attracted

and within an hour the platoon was picked up by a tank lighter and returned to the main lines.15 The other isolated unit, a patrol from Company B, was cut off from the rest of the battalion during the fighting and spent the night of 7-8 November behind the enemy’s lines without detection.

On the morning of 8 November, after a 20-minute preparation by five batteries of artillery augmented by machine guns, mortars, and antitank guns, 1/21 passed through the lines of the 1/3 companies and began the attack. Light tanks, protected by the infantrymen, spearheaded the front. Only a few dazed survivors of two concentrated artillery preparations contested the advance, and these were killed or captured. More than 250 dead Japanese, some of them killed the previous day, were found in the area.16 The battalion from the 21st Marines moved about 1,500 yards through the jungle paralleling the shoreline. No opposition was encountered. That afternoon, 1/21 established a defensive line behind an extensive lagoon17 and sent out strong patrols on mop-up duties. There was no enemy contact.

The following morning, 9 November, the area between the Marine positions and the Laruma River was bombed and strafed by dive bombers from Munda. The air strike completed the annihilation of the Japanese landing force. Patrols from 1/21 later found the bodies of many Japanese in the area, apparently survivors of the attacks of 7 and 8 November who had taken refuge in the Laruma River area. There was no further enemy activity on the left flank of the perimeter, and, at noon of that day, control of the sector passed to the 148th Infantry Regiment of the 37th Division, which had arrived the preceding day. The battalion from the 9th Marines moved to the right flank, and 1/3 returned to regimental reserve in the 3rd Marines area. Fry’s battalion, holding down the left-flank position, remained under operational control of the 148th Regiment until other units of the 37th Division arrived.

The Japanese attempt to destroy the IMAC forces by counterlanding had ended in abject failure. The landing force, woefully small to tackle a bristling defensive position, had only limited chances for success, and these were crushed by the prompt action of Company K, 3/9, and the rapid employment of the available reserve forces, 1/3 and 1/21.

Estimates differ as to the size of the raiding unit which the Japanese sent against a force they believed numbered no more than 5,000 men. Japanese records indicate that 850 men were landed, but IMAC intelligence officers believed that no more than 475 Japanese soldiers were thrown against the defensive perimeter. Most of these were killed in the artillery barrages and the air strike on 7-9 November. The landing site was an unfortunate choice, also. The Japanese had no idea of the exact location of the Allied beachhead and believed it to be farther east around Cape Torokina. The landing was not planned for an area so close to the beachhead. With all tactical integrity lost, forced to attack before they were ready and reorganized, the Japanese were handicapped from the first.

Another factor in the defeat was the Japanese inability to coordinate this counterattack with a full-scale attack on the opposite side of the perimeter, although this was the original intention of the counterlanding. The enemy’s error of carrying situation maps and operation orders into combat was repeated in the Laruma River landing. Within hours of the attack by 1/21 on 8 November, IMAC intelligence officers had the Japanese plan of maneuver against the entire beachhead and were able to recommend action to thwart the enemy strategy.

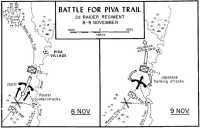

Piva Trail Battle18

The enemy pressure on the right flank of the perimeter began as a series of small probing attacks along the Piva Trail leading into the beachhead fronting Cape Torokina. Japanese activity on this flank, in contrast to the counterlanding effort, was entirely expected. Since D-Day, the 2nd Raider Battalion with Company M of the 3rd Raider Battalion attached had slowly but steadily pressed inland astride the trail leading from the Buretoni Mission towards the Piva River. This trail, hardly more than a discernible pathway through the jungle, was the main link between the Cape Torokina area and the Numa Numa trail; and if the Japanese mounted a serious counterstroke, it would probably be aimed along this route.

Advance defensive positions were pushed progressively deeper along this path by raider companies, and, by 5 November, the Marines had established a strong trail block about 300 yards west of the junction of the Piva-Numa Numa trails. Although the responsibility for the defense of this sector now belonged to the 9th Marines, the 2nd Raider Battalion still maintained the trail block. Until the night of 5-6 November, there had been no interference from the enemy except occasional sniper fire. That night, with Company E of the 2nd Raiders manning the defensive position, the Japanese struck twice in sharp attacks. Company E managed to repulse both attacks, killing 10 Japanese, but during the fight an undetermined number of enemy soldiers managed to evade the trail block and infiltrate to the rear of the raiders.

The following day was quiet, but anticipating further attempts by the Japanese to steamroller past the road block, the 2nd and 3rd Raider Battalions, under regimental control of the 2nd Raider Regiment, were moved into position to give ready support of the road block. The raiders remained attached to the 9th Marines, and Colonel Craig continued to control operations of both regiments.19

The first enemy thrust came during the early part of the afternoon of 7 November, shortly after Company H of the 2nd Raiders had moved up to the trail block to relieve Company F which had been in position the night before. A force of about one company struck the defensive block first; but Company H, aided by quick and effective 81-mm mortar fire from 2/9 in the defensive perimeter to the rear of the trail block, turned the enemy’s assault. One platoon from Company E, 2nd Raiders, then rushed to the trail block to reinforce

Company H until another raider unit, Company G, was in position to help defend the trail. The enemy, unable to penetrate the Marine position after several furious attacks, withdrew about 1530, and was observed digging in around Piva Village, some 1,000 yards east. The Japanese force was estimated at about battalion strength.

Several small-scale attacks were started later that afternoon by the Japanese, but each time the two raider companies called for mortar concentrations from 2/9 and the assaults were beaten back. One determined attempt by the Japanese to cut the trail between the road block and the IMAC perimeter was repulsed by Company G. During the night, the enemy rained 90-mm mortar fire on the trail block and sent infiltrating groups into the Marine lines, but the two raider companies, sticking to their foxholes, inflicted heavy casualties by withholding return fire until the enemy was at point-blank range. One Marine was killed.

Early the next morning, 8 November, Company M of the 3rd Raiders hurried forward to relieve Company H while Company G took over the responsibility for the trail block. Company M took up positions behind the trail block and deployed with two platoons on the left side of the trail and one platoon on the right. Before Company H could leave the area, however, enemy activity in front of Company G increased and returning patrols reported that a large-scale attack could be expected at any time. Reluctant to leave a fight, Company H remained at the trail block. The Japanese assault was not long in coming. Elements of two battalions, later identified as the 1st and 3rd Battalions of the 23rd Infantry from the Buin area, began pressing forward behind a heavy mortar barrage and machine gun fire. By 1100, the trail block was enveloped on all sides by a blaze of gunfire as the Marine units sought to push the attackers back. Company G, solidly astride the trail, bore the brunt of the enemy’s assault.

Shortly after 1100, Company E moved from a reserve area into the trail block and took up positions on the right of Company G. The platoons of Company E were then extended to the right rear to refuse that flank. At this time, the combined fronts of G and E Companies astride the Piva Trail measured about 400 yards. An hour later, at noon, Company L of the 3rd Raiders also advanced from a reserve area and stationed itself on the left flank of Company G. The Marine position now resembled a rough horseshoe, with Companies E, G, and L holding the front and flanks and Companies H and M connecting the trail block to the main IMAC perimeter.

Flanking movements by either the attackers or the defending Marines were impossible because of the swampy ground on either side of the trail, and two attempts by enemy groups to envelop the flanks of the Marine position ended as near-frontal attacks with heavy casualties to the attacking troops. In each instance, the Japanese were exposed to the direct fire of a Marine company in defensive positions. Both attacks were beaten back.

At 1300, with the enemy assault perceptibly stalled, the 2nd Raiders attempted a counterattack. Company F, returned to the trail block from a reserve area, together with Company E began a flanking maneuver from the right. After struggling through the swamps for only 50 yards, the two raider companies struck a large force of Japanese, and the fight for possession of the trail began once more.

Map 17: Battle for Piva Trail, 2nd Raider Regiment, 8–9 November

The enemy soldiers, attempting another counterattack, ran full into the fire of Company G’s machine guns and once again took heavy casualties. Half-tracks of the 9th Marines Weapons Company, with two supporting tanks, moved forward to help the Marine attack gain impetus, but the thick jungle and the muddy swamps defeated the attempts of the machines to reinforce the front lines. Unable to help, the machines began evacuating wounded. By 1600, the fight at the trail block was a stalemate. The Marines were unable to move forward, and the enemy force had been effectively stalled. Another Japanese counterattack, noticeably less fierce than the first, was turned back with additional casualties to the enemy.

With darkness approaching, the raider companies were ordered to return to their prepared lines, and the Marines began to withdraw through the trail block. Company F covered the disengagement and beat back one final enemy attempt before the withdrawal was completed. The raider casualties were 8 killed and 27 wounded. The Marines estimated that at least 125 Japanese had been killed in the day’s fighting.

That night, General Turnage directed Colonel Craig to clear the enemy from the area in front of the 9th Marines and the trail block so that the perimeter could be advanced. Craig, planning an attack with an extensive artillery preparation, decided to use Shapley’s 2nd Raider Regiment again because the raiders were already familiar with the terrain. The attack was to be supported by 2/9 with a section of tanks and half-tracks attached.

At 0620 the following morning, 9 November, the raider units returned to the trail block area which had been held overnight by Company M and a fresh unit, Company I. The two assault companies deployed behind Company I with Company L taking positions on the left of the trail and Company F on the right side of the trail. At 0730, the artillery preparation by 1/12 began to pound into the Japanese positions ahead of the trail block. More than 800 rounds were fired as close as 250 yards from the Marine lines to prepare the way for the attack by the two raider companies.

The Japanese, though, had not waited to be attacked. At first light, the enemy started strong action to overrun the trail block and moved to within 100 yards of the Marine position. There they had established a similar trail block with both flanks resting on an impassable swamp. Other enemy soldiers, who had crept up to within 25 yards of the front lines during the night, remained hidden until the artillery fires ceased and the raider companies began the attack. Then the Japanese opened up with short-range machine gun fire and automatic rifle fire.

The enemy’s action delayed part of Company F, with the result that, when Company L began the attack at 0800, only half of Company F moved forward. Coordination between the two attacking units was not regained, and, by 0930, the raider attack had covered only a few yards. The two companies were forced to move along a narrow front between the swamps, and the enemy fire from a large number of machine guns and “knee mortars” stalled the Marine attack.

Neither the tanks nor the half-tracks could negotiate the muddy corridor to reinforce the Marine attack. Unable to flank the enemy position, the raiders could move forward only on the strength of a concentrated frontal attack. The fight along the corridor became a toe-to-toe slugging match, the Marines and Japanese screaming at each other in the midst of continual mortar bursts and gunfire. Slowly at first, then with increasing speed, the Marine firepower overcame that of the Japanese. The raider attack, stalled at first, began to move.

Threatened by a desperate enemy counteraction on the right flank, Colonel Craig—personally directing the attack of the raiders—moved Company K into the gap between Companies L and F and deployed the Weapons Company of the 9th Marines on the right rear of the trail block for additional support. These moves stopped the Japanese counterattack on that flank. Later, another platoon from Company M moved into the front lines to lend its firepower to the raider advance.

Suddenly, at 1230, the Japanese resistance crumbled and the raider companies pressed forward against only scattered snipers and stragglers. By 1500, the junction of the Piva-Numa Numa Trail was reached, and, since no enemy had been seen for more than an hour, the assault units halted. Defensive lines were dug, and patrols began moving through the jungle and along the Numa Numa Trail. There was no contact, and a large enemy bivouac area along the Numa Numa Trail was discovered abandoned. More than 100 dead Japanese were found after the attack. The Marines lost 12 killed and 30 wounded in the operation.

An air strike set for early the next morning, 10 November, was delayed for a short time by the late return of a patrol from Company K, 3rd Raiders, which had been on an all-night scouting mission to Piva Village. The patrol reported no contacts. Twelve torpedo bombers from Marine squadrons VMTB-143 and -233 based at Munda then bombed and strafed the area from the Marine position to Piva Village. The front lines were marked by white smoke grenades and a Marine air liaison party guided the pilots in their strike. The first bomb fell within 150 yards of the markers. A 50-yard strip on both sides of the Numa Numa Trail was worked over by the planes, and, at 1015, the infantry began moving toward Piva Village.20

Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. Cushman’s 2/9, followed closely by 1/9 commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Jaime Sabater, passed through the raider companies and moved along the trail. The advance was unopposed, although scattered enemy equipment, ammunition, and weapons—including a 75-mm gun and a 37-mm gun as well as rifles and machine guns—were found. Another 30-40 dead Japanese were also found in the area, apparent victims of the extensive air and artillery support of the Marines.

By 1300, the two battalions of the 9th Marines had moved through Piva Village and into defensive positions along the Numa Numa Trail. Aggressive patrols began fanning out toward the Piva River and along the trail, seeking the enemy. The IMAC beachhead, by the end of the day, was extended another 800 yards inland and contact had been established with the 3rd Marines to the left.

The 2nd Raider Regiment, which had taken the full force of the enemy’s attack on the right flank, returned to bivouac positions within the perimeter as the division reserve force. In the space of three days, the threat to the beachhead from either flank had been wiped out by the immediate offensive reactions of the 3rd Marine Division. The attempted mouse-trap play by the Japanese to draw the Marine forces off balance towards the Koromokina flank, to set the stage for a strike from the Piva River area, had been erased by well conducted and aggressive attacks supported by artillery and air. The landing force of nearly 475 Japanese on the left flank had been almost annihilated, and at least 411 Japanese died in the attacks on the right flank.

Another factor in the success of the beachhead was the continued arrival of reinforcements, a testimonial to the foresight of General Vandegrift who had insisted that the buildup of the forces ashore not wait the 30-day interval which had been planned. The 148th Regimental Combat Team of the 37th Division began arriving on 8 November, in time to take over responsibility for the left sector of the perimeter, allowing Marine units in that area to revert to their parent units and bolster the right flank defense. In addition, the arrival of these troops and additional equipment and supplies allowed the perimeter to expand to include a center sector.

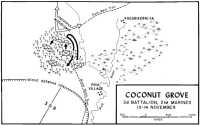

The Coconut Grove21

The second major battle in the vicinity of the Numa Numa Trail began after a two-day lull following the seizure of Piva Village. During that interval, only minor skirmishes occurred, most of them inadvertent brushes between Marine scouting patrols and Japanese stragglers. Although contact with the main force of the enemy had been lost, there was little doubt that the enemy was still present in large numbers north of the Piva River. The 9th Marines, holding the area around Piva Village, concentrated on improving the supply routes into its position. Defensive installations and barriers were also extended and strengthened.

As the beachhead slowly widened behind the 3rd and 9th Marines, airfield reconnaissance efforts were extended, and, during the time that the trail block fighting was underway, a group of Navy and Marine engineers with construction battalion personnel were busy making a personal ground reconnaissance of an area which had earlier been selected as a possible airfield site. This location, about midway between the Koromokina and Piva Rivers, was about 5,500 yards inland or about 1,500 yards in advance of the 3rd Marine Division positions.

The engineers, accompanied by a strong combat patrol, managed to cut two 5,000-foot survey lanes nearly east to west across the front of the IMAC perimeter. The patrol then returned to report that at least one bomber strip and one fighter strip could be constructed in the area scouted. The survey party was unchallenged by the enemy, although a combat patrol the following day clashed with a Japanese patrol near the same area.

Because the numerous swamps and difficult jungle terrain prohibited the possibility of extending the beachhead immediately to cover the proposed airfield site, General Turnage decided that a combat outpost, capable of sustaining itself and defending the selected area until the front lines could be lengthened to include it, should be established at the junction of the Numa Numa and East-West Trails. On 12 November, the division commander directed the 21st Marines (Colonel Evans O. Ames) to send a company-sized patrol up the Numa Numa Trail the following morning. This group was to move to the junction of the two trails and reconnoiter each trail for a distance of 1,000 yards. This would delay any Japanese attempts to occupy the area, and would prevent having to fight an extended battle later for its possession.

At this time, the 21st Marines had two battalions ashore and a third due to land within the next few days. Fry’s battalion was still in support of the 37th Division on the left, and 2/21 (Lieutenant Colonel Eustace R. Smoak) was then in bivouac near Cape Torokina. Smoak’s battalion, with the regimental command post group, had arrived on 11 November. Alerted for action, 2/21 moved to a new bivouac area about 400 yards behind the 9th Marines and waited for orders.

On the night of 12 November, the division chief of staff (Colonel Robert E. Blake) directed that the size of the patrol be increased to two companies with a suitable command group and artillery observers to establish a strong outpost at the trail

Map 18: Coconut Grove, 2nd Battalion, 21st Marines, 13–14 November

junction. Aware of the importance of the mission, Smoak requested and received permission to use his entire battalion in the assignment.

At 0630 the following morning, 13 November, Company E as the advance unit of 2/21 moved to the assembly area behind the 9th Marines but was ordered to hold up at this point. An hour later, with the remainder of the battalion still engaged in drawing ammunition, water, and rations, Company E was directed to begin the advance. The remainder of the battalion would follow as soon as possible. An artillery observer party, attached to the battalion, failed to arrive until after Company E had departed.

The rifle company cleared the 9th Marines perimeter at 0800, and three hours later was ambushed by a sizeable enemy force located in an overgrown coconut palm grove about 200 yards south of the trail junction which was the objective. Company E deployed to return the fire, but mortar shells and machine gun fire restricted movement and casualties began to mount.

The enemy had won the race for the trail junction.

Although it is possible that the Japanese had been in an organized position in the coconut grove for some time, it is unlikely that the airfield reconnaissance patrol would have been allowed to operate without attack if such were the case. A better possibility is that the Japanese moved into the position coincidental with the decision by Turnage to establish an outpost there.

Smoak’s battalion, at that time some 1,200 yards to the rear of Company E, received word of the engagement at 1200. The battalion, pulling in its slower moving flank security patrols, hurried up the trail toward the fight. By 1245, 2/21 was about 200 yards behind Company E and a number of disturbing and conflicting reports were being received. The battalion commander was told that Company E was pinned down by heavy fire and slowly being annihilated. A personal reconnaissance by an officer indicated that the company had taken severe casualties and needed help immediately. While artillery assistance was ordered, Smoak sent Company G forward to help the beleaguered Company E, and Company H was ordered to set up 81-mm mortars for additional support.

In the meantime, more conflicting reports were received as to the enemy’s location and the plight of Company E. As might be expected, several of the messages bordered on panic. Smoak then moved his own command group nearer to the fire fight, and sent Company F forward so that Company E could disengage and withdraw to protect the battalion’s right flank. Company G was directed to maintain its position on the left.

In a matter of moments, the combat situation deteriorated from serious to critical. Company F failed to make contact with Company E, the battalion executive officer became a casualty, and a gaping hole widened in the Marines’ front lines. Company E, not as badly hurt as had been first reported, was rushed back into the lines and established contact with Company G. There was no sign of Company F. At 1630, with communication to the regimental command post and the artillery battalions knocked out, Smoak ordered his companies to disengage and withdraw from the coconut grove. A defensive line was established several hundred yards from the enemy position.

Shortly after the Marines began to dig in along the trail, a runner from Company F returned to the lines to report that Company F—failing to make contact with Company E—had continued into the Japanese position and had penetrated the enemy lines. The company had taken heavy casualties, was disorganized, and seeking to return to the 2/21 lines. Smoak ordered the runner to guide the company around the right flank of the Marine position into the rear of the lines. The missing company returned, as directed, about 1745. At 1830, communication with the regimental CP and the artillery battalions was restored, and artillery support requested. Concentrations from 2/12 were placed on the north, east, and west sides of the battalion’s lines; and the 2nd Raider Battalion, now attached to the 21st Marines, was rushed forward to protect the communication and supply lines between 2/21 and the regiment. There were no enemy attacks and only sporadic firing during the night.

The following morning, despite sniper fire, all companies established outposts and sent out patrols in preparation for a coordinated attack with tank support. A scheduled air strike was delayed until the last of these patrols were recalled to positions within the Marine lines. At 0905, the 18 Navy torpedo bombers then on station began bombing the coconut grove and the area between the enemy position and the Marine perimeter. A Marine air-ground liaison team directed the strike. Artillery smoke-shells marked the position for the aviators, who reported that 95 percent

of the bombs fell within the target area. Bombs were dropped as near as 100 yards from the forward Marine foxholes.

Unfortunately, the ground attack was delayed until 1100 by the need to get water to the troops, so that the effect of the air strike was lost. A break in communications further delayed the attack, and new plans were made for an attack at 1155. A 20-minute artillery preparation followed by a rolling barrage preceded the assault. At 1155, 2/21 began moving forward, Company E on the left and Company G on the right with Companies F and H in reserve. Five tanks from Company B, 3rd Tank Battalion, were spaced on line with the two assault companies.

In a short time, the attack had stalled. The Japanese soldiers had reoccupied their positions; and the enemy fire, plus the noise of the tanks and the rolling barrage, resulted in momentary loss of attack control. The tanks, depending upon the Marine infantry for vision, lost direction and at one point were directing fire at Marines on the flank. One tank was knocked out of commission by an enemy mine, and another was stalled by a hit from a large caliber shell. The battalion commander, seeing the confusion, ordered the attack to cease and the companies to halt in place. This act restored control, and after the three remaining tanks were returned to a reserve position, the attack was continued behind a coordinated front. The enemy positions were overrun, and the defenders killed. Mop-up operations were completed by 1530, and a perimeter around the position was established. Only about 40 dead Japanese were found, although the extent of the defensive position indicated that the enemy strength had been greater. The Marines lost 20 killed (including 5 officers) and 39 wounded in the two days of fighting.

The 2nd Battalion emerged from this battle as a combat-wise unit. A series of events, unimportant on the surface, had resulted in serious consequences. The attack on 13 November with companies committed to action successively without prior reconnaissance or adequate knowledge of the situation was not tactically sound. Company E was beyond close supporting distance when attacked, and the conflicting reports on the number of casualties forced the battalion commander to push his remaining strength forward as quickly as possible. These units were engaged prematurely and without plan. The orderly withdrawal on 13th of November, and the prompt cessation of the attack on 14 November when control was nearly lost, was convincing evidence that 2/21 was rapidly gaining combat stability. The last well-coordinated attack was final proof.

In view of the bitter fighting later, the lack of preparatory artillery fires before Company E began its advance on 12 November has been pointed out as a costly omission. Actually, had the presence of the extensive and well-organized Japanese position been determined by prior reconnaissance, the support of this valued arm would have been used. Marine commanders were well aware that infantry attacking prepared defenses would sustain heavy casualties unless the assaults were preceded by an effective combination of the supporting arms—air, artillery, or mortars.

The seizure of the coconut grove area allowed the entire beachhead to leap forward another 1,000 to 1,500 yards. By 15 November, the IMAC perimeter extended

to the phase line previously established as Inland Defense Line D.

Defense of the Cape Torokina Area22

In the first two weeks of operations on Bougainville, the Marine-Army perimeter had progressed to the point where nothing less than an all-out effort by major Japanese forces could endanger its continued success. From the long and shallow toehold along Empress Augusta Bay on D-Day, the IMAC perimeter gradually crept inland until, on 15 November, it covered an area about 5,000 yards deep with a 7,000-yard base along the beach. Included within this defensive area were the projected sites of a fighter strip at Torokina and fighter and bomber strips near the coconut grove.

The expansion of the beachhead and the arrival of the first echelons of the 37th Division marked a change in the command of the troops ashore. General Turnage had been in command of the 3rd Marine Division and all IMAC troops on the beachhead since D-Day;23 but after the arrival of the Army troops, IMAC once more took up the command of all forces ashore. On 9 November, Vandegrift relinquished command of the Marine amphibious corps to Major General Roy S. Geiger, another Guadalcanal veteran, and returned to the United States. With the arrival of the second echelon of the 37th Division on 13 November, its commander, Major General Robert S. Beightler, assumed command of the Army sector of the perimeter.

The enemy’s attempts to bomb the beachhead after D-Day were sporadic and uncoordinated. The fighter cover of ComAirSols, which included Marine Fighter Squadrons -211, -212, -215, and -221, permitted few interlopers to penetrate the tight screen; and the Japanese—after the losses taken in the strikes of 1 and 2 November—could not mount an air attack of sufficient size and numbers to affect the beachhead defenders. The enemy air interference over Cape Torokina was limited to a few night raids, and these were intercepted by Marine planes from VMF(N)-531.

During the first 15 days of the beachhead, there were 52 enemy alerts, 11 bombings, and 2 strafing attacks. The only significant damage was done in a daylight raid of 8 November during the unloading of a follow-up echelon of troops and supplies. More than 100 Japanese fighters and carrier bombers jumped the 28 badly outnumbered AirSols planes, and, during the air melee over the beachhead, the transport Fuller was bombed. Five men were killed and 20 wounded. A total of 26 Japanese planes were claimed by the Allied fighters. Eight AirSols planes, including one from VMF-212, were lost.

In the first days of the beachhead, the responsibility for turning back any coordinated sea and air operations by the Japanese rested with the overworked cruiser-destroyer forces of Admiral Merrill and the planes of ComAirSols. Admiral Halsey, weighing the risk of carriers in enemy waters against the need to cripple further the enemy’s strength at Rabaul, on 5 November

sent Admiral Frederick C. Sherman on a dawn raid against New Britain with the carriers Saratoga and Princeton. Despite foul weather, the carrier planes—97 in all—found a hole in the clouds and poured through to strike the enemy fleet at anchor in Simpson Harbor. The planes reported damage to four heavy and two light cruisers and two destroyers.

Six days later, three carriers (Essex, Bunker Hill, and Independence) on temporary loan from Nimitz’ Central Pacific fleet struck from the east while Sherman’s force hit from the south. The 11 November strike found few targets. The enemy fleet was absent from Rabaul; but the carrier planes knocked 50 Japanese interceptors out of the air and worked over the few ships in the harbor. The two raids ended the Japanese attempts to destroy the Bougainville beachhead by concerted air and sea action.

While the perimeter had been slowly pushed inland, the arrival of additional troops and supplies strengthened the IMAC position. By the time of the arrival of the third echelon on 11 November, beach conditions were more favorable and facilities to allow quick unloading were developed. The third and fourth echelons were unloaded and the ships headed back towards Guadalcanal within the space of a day. During the period 1-13 November, the following troops, equipment, and supplies were delivered to the beachhead:24

| Date | Echelon | Ships | Troops | Cargo tons |

| 1 Nov | 1 | 8 APA, 4 AKA | 14,321 | 6,177 |

| 6 Nov | 2 | 8 APD, 8 LST | 3,548 | 5,080 |

| 8 Nov | 2A | 4 APA, 2 AKA | 5,715 | 3,160 |

| 11 Nov | 3 | 8 APD, 8 LST | 3,599 | 5,785 |

| 13 Nov | 4 | 4 APA, 2 AKA | 6,678 | 2,935 |

| Total | 33,861 | 23,137 |