Chapter 5: Advance to Piva Forks

The Japanese Viewpoint1

Throughout the first weeks of operations on Bougainville, there was no indication that the Japanese were aware of the true intentions of the I Marine Amphibious Corps and its activities at Cape Torokina. Had the enemy guessed that the Allied purpose was limited only to the construction and defense of several airfields and a naval base in preparation for further operations, the Japanese might have objected more strenuously to the presence of uninvited co-tenants. But the Seventeenth Army, hesitating to commit the forces available at Buin before being more certain of Allied plans, held back.

The lack of immediate and continued aggressive action against the IMAC beachhead was a sore point between the Japanese sea command in the Southeast Area and the Seventeenth Army, which still chose to take a lighter, more optimistic view of the situation than the Navy. Admiral Kusaka’s Southeast Area Fleet contended that if the Allies constructed an airfield at Torokina, further Japanese operations on Bougainville would be impractical and sea movements impossible. General Hyakutake, though, argued that the Allies would occupy a base of operations and then at the first opportunity attempt to occupy the Buin sector with the main force while striking the Buka sector with other elements. In such a case, the Seventeenth Army explained, it was better to intercept such movements from prepared positions in the Buin and Buka sectors than to abandon these established positions to counterattack at Torokina.2

This may have been wishful thinking. Hyakutake was well aware of his own situation—there were no good roads leading into the Allied position over which the Seventeenth Army could mount a counteroffensive, and barges were in short supply. Two attempts to wipe out the beachhead had resulted in crushing defeats, and the Navy’s ill-timed Ro offensive had likewise ended with heavy losses. Reluctantly, the Japanese finally admitted what Allied planners had gambled on some time before—that a decisive counterstroke against the beachhead could not be undertaken for some time.

Despite this estimate, the Allies kept a wary eye on the enemy dispositions in the Bougainville area. Aerial reconnaissance to the north disclosed that the Japanese were constructing extensive defenses in the Buka area to keep their one remaining airfield in operation. The Allies reasoned that if the enemy was committed to a defense of Buka, then he was not likely to

draw troops from there for an offensive in the Empress Augusta Bay area. This removed one threat to the beachhead.

The main danger to the Allied position, however, was from the south where the bulk of the 6th Division and, therefore, most of the Seventeenth Army was located. The Japanese, moving by barge from Buin to Mawareka could strike overland from that point. The meager trail net from Mosigetta and Mawareka was the logical route of approach to Cape Torokina, and reliable intelligence reports indicated that these paths could be traveled by pack animals as well as by troops. This gave the Japanese the added capability of packing artillery into the area to support an attack. The overhanging jungle foliage would screen any movements of troops and make the task of detection more difficult.

A coastwatcher patrol kept the trails to Mosigetta and Mowareka under close surveillance. Daily air searches and photographs were made of the beaches in southern Empress Augusta Bay to detect evidence of enemy landings during the night. In addition, captured enemy letters, diaries, notebooks, and plans were processed and interpreted by intelligence officers for further information. These documents and interrogations of a few prisoners gave a comprehensive order of battle for the immediate area and some approximation of forces. The Japanese apparently had no immediate plans for a counterstroke. The constant and alert protection of the combat air patrol over Bougainville and the expanded and increased activity of Allied ships in southern Bougainville waters undoubtedly played a major role in discouraging the enemy from exercising this capability.

Supply Problems3

A number of changes in the disposition of IMAC units within the perimeter had been made during the widening of the beachhead to the 15 November line. After General Geiger took command of the Marine amphibious corps, all units temporarily attached to the 3rd Marine Division for the landing reverted to IMAC control once more, and defensive installations within the beachhead were improved and strengthened.

The Marine 3rd Defense Battalion, supported by long-range radar installations, continued to provide antiaircraft and seacoast artillery protection for the beachhead and offshore islands. All field artillery units—both Marine Corps and Army—were placed under central command as an IMAC artillery group to be available as massed fires for interdiction, neutralization, counterbattery, beach defense, or attack support. Brigadier General Leo M. Kreber of the 37th Division was designated commander of the artillery group. A corps reserve was established by withdrawing most of Lieutenant Colonel Shapley’s 2nd Raider Regiment from the front lines. This reserve was then held in readiness for counterattacks in any sector of the perimeter or for quick reinforcement of the front line defenses.

Following the battle of the Coconut Grove, contact with the main forces of the enemy was lost once more and the period was one of relative inactivity by

the Japanese. Perimeter units of the 3rd Marine Division and the 37th Division continued active combat patrolling, but there were few enemy contacts. The Japanese had apparently withdrawn. The activity by the IMAC forces was mainly to fix the location of enemy troops and to obtain information on the terrain ahead in preparation for the continuing expansion of the beachhead. After 15 November, these offensive moves were made to improve the defensive positions of the perimeter, and the attack objectives were usually just lines drawn on a map a certain distance from an established position. These moves to new phase lines were more in the nature of an active defense.

The 37th Infantry Division, during this period, found the expansion of the perimeter in its sector much less difficult than the Marines did in their sector. There was little enemy activity in front of the 148th and 129th Infantry Regiments after the Koromokina engagement, and the Army units received only glancing blows from scattered Japanese groups. Once the beachhead was carried past the outer limits of the swampy plains toward higher ground, the infantry regiments were on fairly firm terrain and could move without too much trouble. This sector of the beachhead also took on added strength as more Army support units continued to arrive with later echelons of shipping. After the movement to Inland Defense Line D, General Geiger allowed General Beightler to expand the 37th Division sector of the beachhead, coordinating with the Marine efforts only at the central limiting point on the boundary line between divisions. The lack of aggressive enemy action in front of the two Army regiments permitted the perimeter in this sector to advance more rapidly. This situation, in regard to enemy opposition, continued throughout the campaign until March 1944.

The Marine half of the perimeter at this time, in contrast to the area held by the 37th Division, was still marked by lagoons and swamplands. In most places, the front lines could be reached only by wading through water and slimy mud which was usually knee deep, was often waist deep, and sometimes was up to the arm pits. The defensive perimeter in the Marine sector actually consisted of a number of isolated positions, small islands of men located in what was known locally as “dry swamp”—meaning that it was only shoe-top deep.4 The frequent downpours discouraged attempts to dig foxholes or gun emplacements. Machine guns were lashed to trees, and Marines huddled in the water. In this sultry heat and jungle slime, travel along the line was extremely difficult, and resupply of the frontline units was a constant problem.5

Improvement of the supply lines to the perimeter positions was the greatest concern of IMAC at this time. The seemingly bottomless swamps through which supply roads had to be constructed were a dilemma whose early solution appeared at times to be beyond the capabilities of the available road-building equipment and material. The move to Line D took in the site of the projected bomber and fighter strips near Piva, and although the

field telephone lines, the primary means of communication in the jungle, are laid by armed Marine wiremen on Bougainville. (USMC 67228B)

bomber field was already surveyed, construction was held up by the lack of access roads to the area. The diversion of equipment and resources to the construction of roads and supply trails instead of airfields handicapped the work which had begun on the fighter strip at Torokina and delayed the start of the Piva bomber strip, but the problem of supply was too pressing to be ignored.

By 16 November, the lateral road across the front of the perimeter was completed after two weeks of feverish activity. During the time of the Piva Trail and Coconut Grove engagements, the 3rd Battalion of the 3rd Marines had pushed the construction of this supply road as fast as the limits of men and machines would permit. The speed was dictated by the need to keep pace with the assault battalions which were seeking the main enemy positions before the Japanese could consolidate forces and prepare an established defense in depth. Engineers moved along with the 3rd Battalion as the Marines moved inland. On more than one occasion, bulldozer operators had to quit the machines and take cover while Marine patrols skirmished with enemy groups in a dispute over the right of way.

The end product was a rough but passable one-lane roadway which followed the path of least resistance, skirting along the edge of the swampy area. The road began near the Koromokina beaches, then wound inland for several thousand yards before cutting to the southeast toward the coconut grove and the Piva River. Small streams were bridged with hand-hewn timbers, and muddy areas were corduroyed with the trunks of fallen trees. In many instances, trucks were used to help batter down brush and small trees, with resultant damage to vitally needed motor transport. Dispersal areas were limited, and there was much needed work to be done on access, turn-around, and loop roads. But this rutted and muddy roadway joined the two sectors of the beachhead to the dumps along the shoreline and greatly aided the supply and evacuation problems of the frontline battalions.

As the latoral road was cut in front of 2/3, this battalion advanced about 1,000 yards inland to protect the roadway and to cover the widening gap created between the two divisions by the continual progress of 3/3 toward the Piva River. The road construction force and 3/3 broke out of the jungle at the junction of the Numa Numa and Piva trails on 16 November, having connected the lateral road with the amphibian tractor trails from the Cape Torokina area. Although rains sometimes washed out the crude trailway and mired trucks often stalled an entire supply operation, the roadway was assurance that the IMAC forces could now make another offensive-defensive advance, confident that the essential supplies would reach the front lines.

The critical supply situation had been corrected by an abrupt revision of the original plans. The rapidly changing tactical circumstances and the redisposition of combat elements along the beachhead left the beaches cluttered with all classes of supplies and equipment. After some semblance of order had been restored, it was apparent that the landing teams could not handle and transport their own supplies as had been planned. The battalions, striking swiftly at the Japanese, moved inland with what they could carry. Within a short time, most of the units were miles from their original shore party dumps. These were practically abandoned and became a source of supply on a first-come,

first-served basis to all units of the I Marine Amphibious Corps. Rations and ammunition were picked up by most units at the first available source.

The first corrective action by the Marine division’s G-4 and the division quartermaster was to direct that all shore party dumps revert to division control. A new plan was outlined under which the division quartermaster assumed responsibility for control and issue of all supplies in the dumps and on Puruata Island.6 A division dump or distribution point was established adjacent to the plantation area on Cape Torokina. All supplies littering the beach were recovered and returned to this area. Succeeding echelons of supplies and equipment arriving at the beachhead were also placed in this dump for issue by the division quartermaster.

Before the completion of the lateral road and control of supplies by the division quartermaster, the battalions holding the perimeter were supplied on a haphazard schedule by the versatile amphibian tractors. When the new program was effected, supplies were virtually leap-frogged forward in a relay system that involved handling of the same stocks as many as four times. This system, however, provided for an equitable distribution of ammunition and rations to all units. From the division dump at the beach, supplies were carried to regimental dumps, which in turn issued to the battalions. Trucks carried the supplies as far forward as possible, then amphibian tractors took over. As the battalions advanced, forward supply points were set up. An attempt was made to build up an emergency supply level at each of these forward points. The front lines, however, moved ahead so steadily that usually an untracked jungle stretched between the troops and their supply dumps. The LVTs, when possible, skipped these forward points to continue as close to the front lines as they could manage.

A total of 29 of these LVTs had been landed with the assault waves on D-Day and more arrived in later echelons. Their contribution to the success of the beachhead, however, was in far greater proportion than their number. Without the 3rd Amphibian Tractor Battalion (Major Sylvester L. Stephen), the operation as planned could not have been carried beyond the initial beachhead stages; and it was the work of the LVT companies and the skill of the amtrac operators that made possible the rapid advance of the IMAC forces during the first two weeks. The tractors broke trails through the swamps and marshes, ploughing along with vital loads of rations, water, ammunition, weapons, medical supplies, engineer equipment, and construction materials. Even towing the big Athey trailers, the LVTs were able to move over muddy trails which defeated all wheeled vehicles; and, in fact, the broad treads of the trailers sometimes rolled out and restored rutted sections of roadways so that jeeps could follow.

As might be expected, the maintenance of these machines under such conditions of operation became a problem. Many amtracs were in use continually with virtually no repairs or new parts. As a result, numerous tractors were sidelined

because of excessive wear on channels and tracks caused by the constant operation through jungle mud. The largest number of machines available at one time was 64, but the number of tractors still in service declined rapidly after the first two weeks. Ironically, by the time that a major battle between the Marine forces and the Japanese appeared likely (24 November), the number of amtracs available for use was 29—the same number that was available on D-Day.

Combat Lessons7

Throughout this period, the individual Marine (and his Army counterpart in the 37th Division) learned how to battle both the Japanese and the jungle. For two weeks the Marines had struggled through swamps of varying depth, matching training and skill against a tenacious and fanatic enemy. This fight for survival against enemy and hardship in the midst of a sodden, almost impenetrable jungle had molded a battlewise and resourceful soldier, one who faced the threat of death with the same fortitude with which he regarded the endless swamps and forest and the continual rain. Danger was constant, and there were few comforts even in reserve bivouac positions.

The combat Marine lived out of his marching pack with only a few necessities—socks, underwear, and shaving gear—and a veritable drug store of jungle aids such as atabrine tablets, sulpha powders, aspirin, salt tablets, iodine (for water purification as well as jungle cuts and scratches), vitamin pills, and insect repellent. Dry clothes were a luxury seldom experienced and then only when gratuitous issues of dungarees, underwear, and shoes were made. Knapsacks and blanket rolls seldom caught up with the advancing Marines, and most bivouacs were made in muddy foxholes without the aid of covering except the poncho—which served a variety of uses.

Troops received few hot meals, since food could not be carried from kitchens through the swamps and jungle to the perimeter positions. Besides, there were no facilities for heating hot water for washing mess kits if hot food could have been brought forward. Troops generally ate dry rations, augmented by canned fruit and fruit juices, and waited for cooked food until they were in reserve positions. When the combat situation and the bivouac areas in the swamps permitted, Marines sometimes combined talents and rations and prepared community stews of C-rations, bouillon powder, and tomato juice which was heated in a helmet hung over a fire. Only the canned meat or cheese, the candy bar, and the cigarettes were taken from the K-rations; the hardtack biscuits found little favor and were usually thrown away. After the beachhead became more fully established, bread was supplied by regimental bakery units and delivered to the front lines. The bread was baked daily in the form of handy rolls, instead of large loaves, which helped solve the problem of distribution to Marines in scattered positions.

Heat tabs met with varied reaction until the Marines found that at least two tabs were required to boil a canteen cup of water. Experience also taught that C-rations could be cooked twice as fast over one heat tab if the ration was divided in half. The first half-can could be heated,

then eaten while the second half-can was heating.

During the Marine advance, there was little water brought forward, and most of the drinking water was obtained from swamp holes and streams. This was purified individually by iodine or other chemicals supplied by the Navy Corpsman with each platoon. Despite this crude sanitation and continued exposure to jungle maladies, there were few cases of dysentery. The 3rd Marine Division, as a whole, maintained a healthy state of combat efficiency and high morale throughout the entire campaign.

The Marines, after defeating the Japanese in three engagements, were becoming increasingly skilled jungle fighters, taking cover quickly and quietly when attacked and using supporting weapons with full effectiveness. Targets were marked by tracer bullets, and the Marines learned that machine guns could be used to spray the branches of trees ahead during an advance. This practice knocked out many enemy snipers who had climbed trees to scout the Marine attack. Although visibility was usually restricted by the close jungle foliage, the Marines learned to take advantage of this dense underbrush to adjust supporting fires almost on top of their own positions. This close adjustment discouraged the Japanese from moving toward the Marine lines to seek cover during a mortar or artillery barrage.

In the jungle, 60-mm mortars could be registered within 25 yards of the Marine positions, 81-mm mortars and 75-mm pack howitzers within 50 yards, and 105-mm howitzers within 150 yards. The latter shell was particularly effective in jungle work, as were the canister shells used in direct fire by the 37-mm antitank guns. Both stripped foliage from hidden enemy positions, exposing the emplacements to a coordinated attack. Although the 60-mm and 81-mm mortars were virtually ineffective against emplacements with overhead cover, both shells were valuable in stopping attacks by troops in the open and in keeping the Japanese pinned to an area being hit by artillery.

Artillery was usually adjusted by sound ranging. The artillery forward observer, estimating his position on the map by inspection, requested one round at an obvious greater range and then adjusted the fire by sound into the target. The location of the target was then determined by replot, and the observer was able then to locate his position as well as the front lines.

Mortar fire was restricted in many cases by the overhanging jungle. Because most fighting was conducted at extremely close range, the mortar rounds in support were fired almost vertically with no increments. When there was any doubt about foliage masking the trajectory, a shell without the arming pin removed was fired. If the unarmed shell cleared, live rounds followed immediately.

Movement through the jungle toward Japanese positions was usually made in a formation which the 3rd Marine Division called “contact imminent.” This formation, which insured a steady, controlled advance, had many variations, but the main idea was a column of units with flank guards covering the widest front possible under conditions at the time. Trails were avoided. A security patrol led the formation; and as the column moved, telephone wire was unrolled at the head of the formation and reeled in at the rear. At the instant of

stopping, or contact with the enemy, company commanders and supporting weapons groups clipped hand telephones onto the line and were in immediate contact with the column commander. Direction and speed of the advance was controlled by the officer at the head of the main body of troops. A command using this formation could expect to make about 500 yards an hour through most swamps. Such a column was able to fend off small attacks without delaying forward movement, yet was flexible enough to permit rapid deployment for combat to flanks, front, or rear. This formation was usually employed in most advances extending the defensive sectors of the perimeter.

Holding the Marine front lines at this time were the 3rd Marines on the left and the 9th Marines on the right. Although Colonel McHenry’s 3rd Marines had responsibility for the left subsector, only one battalion, the 3rd, was occupying perimeter positions. The 1st Battalion was in reserve behind 3/3, and the remaining battalion, 2/3, was attached temporarily to the 129th Infantry in the Army sector. During this time, however, two battalions of the 21st Marines were attached to Colonel McHenry’s command for patrol operations. Elements of 2/21 took part in numerous scouting actions along the East-West trail past Piva Village to develop the enemy situation in that area; 1/21 moved into reserve bivouac positions behind the 3rd Marines.

On the 17th of November, the convoy bearing 3/21 (Lieutenant Colonel Archie V. Gerard) was attacked by Japanese aircraft off Empress Augusta Bay, and the APD McKean was hit and sunk. At least 38 Marines from 3/21 were lost at sea. Two days later, as 3/21 prepared to join the remainder of the regiment near the front lines, the battalion’s bivouac position near the beach was bombed by the Japanese and another five Marines were killed and six wounded. Gerard’s battalion joined the 3rd Marines for operations the same day. Without having been in action against the enemy, 3/21 had already lost as many men as most frontline battalions.

The 9th Marines, at this time, occupied positions generally along the west bank of the Piva River. Amtracs were the only vehicles which could negotiate the swamp trails from the beaches, and the supply situation in this sector was critical. Most of the 9th Marines’ units were forced to take working parties off the front lines to hand-carry supplies forward and to break supply trails into the regiment’s position. Evacuation of wounded was also by hand-carry. The period after the movement to Phase Line D was spent improving the defensive position, seeking enemy activity, and gathering trail information. A number of patrols moved across the Piva River looking for enemy action, but there were few contacts in the several days following the final Coconut Grove action.

The Battle of Piva Forks8

Combat activity in the Marine sector picked up again on the 17th and 18th of November after all units had devoted several days to organization of the defensive perimeter and extension and improvement

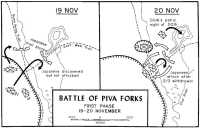

of supply lines. The 37th Division sector remained relatively inactive, with few reports of enemy sighted. Marine units started aggressive patrolling in search of routes of advance and terrain information as far out ahead as the next phase line to be occupied by the 21st of November (Inland Defense Line E). There were minor skirmishes with enemy outposts as the Marines scouted the jungle, but the flareups were brief and there were few casualties to either side. In the 9th Marines subsector, both 1/9 and 2/9 reported that enemy activity had increased, and the 3rd Marines reported that all units along the line had been in contact with small parties of Japanese. A patrol from 3/3 successfully ambushed a Japanese group, killing eight enemy soldiers and one officer who had in his possession a sketch of Japanese dispositions to the immediate front. The drawing, and other captured documents, indicated that the enemy was preparing extensive defenses along both the Numa Numa and the East-West trail.

Another patrol from 3/3, moving down the Numa Numa trail on 18 November, discovered an enemy road block about 1,000 yards to the front. A patrol from 1/21, probing along the East-West trail, encountered a similar enemy position about halfway between the two branches of the Piva River. This was further evidence of Japanese intentions for a determined defense of this area, and plans were made for an immediate attack. The 3rd Raider Battalion was attached to the 3rd Marines to release 3/3 (Lieutenant Colonel Ralph M. King) for the reduction of the Numa Numa trail position the following day.

King’s battalion, accompanied by light tanks, cut through the jungle to the left in front of the 129th Infantry subsector. After an artillery preparation, the battalion struck the enemy position in a flanking attack that completely routed the Japanese. A total of 16 dead enemy were found, although more than 100 foxholes indicated that at least a reinforced company had occupied the position. King’s battalion immediately took possession of the trail block and established a perimeter defense at the junction of the Numa Numa trail and the Piva River. Meanwhile, 1/3 and 1/21 had advanced without difficulty, opposed only by a few bypassed survivors from King’s attack. The 3rd Raiders then moved forward to be available for support, and 2/3—released from operational control by the 129th Infantry—also started east behind the Numa Numa trail toward an assembly area. The march was made under fire; the Japanese sporadically shelled the advancing battalion with 90-mm mortars.

The following morning, 20 November, the same Japanese company that had been forced to withdraw the previous day came bouncing back, full of fight. The enemy attempted to outflank the Marine positions along the trail, but King’s battalion drove the enemy back again. The Japanese then undertook to harass the Marines by sniper fire and mortar concentrations, and the resistance grew more determined when King’s force started a counterattack.

Two of the light Marine tanks were disabled in the close fighting along the trail before the Marine battalion could advance. The general course of attack by 3/3 was east along the Numa Numa trail toward the two forks of the Piva River.

A number of changes in the front line dispositions were ordered as 3/3 advanced. The 3rd Raider Battalion moved out of reserve positions to cover the slowly widening gap between the 129th Infantry and the 3rd Marines. At the same time, Lieutenant Colonel Hector de Zayas’ 2/3 on the right of 3/3 passed through the front lines of 2/21 to advance across the west fork of the Piva River. The objective of 2/3 was the enemy position reported earlier between the two forks of the Piva River. The Piva crossing was made over a hasty bridge of mahogany timbers thrown across the stream by engineers. The enemy outpost was then discovered abandoned but clumsily booby-trapped. The only opposition to the attack by 2/3 was scattered snipers and several machine gun nests. By late afternoon of the 20th, de Zayas’ battalion was firmly astride the East-West trail between the two forks of the Piva River. Elements of the 21st Marines, now in reserve positions behind the two battalions of the 3rd Marines, moved forward to take up blocking positions behind Colonel McHenry’s regiment.

As the Marine forces prepared to continue the attack, the opportune discovery of a small forward ridge was a stroke of good fortune that ultimately assured the success of the Marine advance past the Piva River. This small terrain feature, which was later named Cibik Ridge in honor of the platoon leader whose patrol held the ridge against repeated Japanese assaults, was reported late on the afternoon of the 20th. The area fronting the 3rd Marine positions had been scouted earlier, but this jungle-shrouded elevation had escaped detection. Although the height of this ridge was only 400 feet or so, the retention of this position had important aspects, since it was the first high ground discovered near the Marine front lines and eventually provided the first ground observation posts for artillery during the Bougainville campaign. There is no doubt that the enemy’s desperate attempts to regain this ground were due to the fact that the ridge permitted observation of the entire Empress Augusta Bay area and dominated the East-West trail and the Piva Forks area.

All this, however, was unknown when First Lieutenant Steve J. Cibik was directed to occupy this newly discovered ridge. His platoon, quickly augmented by communicators and a section of heavy machine guns, began the struggle up the steep ridge late in the afternoon of the 20th. Telephone wire was reeled out as the platoon climbed. Just before sunset, the Marines reached the crest for the first look at the terrain in 20 days of fighting. Daylight was waning and the Marines did not waste time in sightseeing. The remaining light was used to establish a hasty defense, with machine guns sited along the likely avenues of approach. Then the Marines spent a wary night listening for sounds of enemy.

The next morning Cibik’s men discovered that the crest of the ridge was actually a Japanese outpost position, used during the day as an observation post and abandoned at night. This was confirmed when Japanese soldiers straggled up the opposite slope of the ridge shortly after daybreak. The enemy, surprised by the unexpected blaze of fire from their own outpost, turned and fled down the hill.

Map 19: Battle of Piva Forks, First Phase, 19-20 November

After that opening move, however, the enemy attacks were organized and in considerable strength. Cibik’s platoon, hastily reinforced by more machine guns and mortars, held the crest despite fanatical attempts by the Japanese to reoccupy the position. The Marines, grimly hanging to their perch above the enemy positions, hurled back three attacks during the day.

The expansion of the beachhead to Inland Defense Line E jumped off at 0730 on the morning of 21 November. The general plan called for a gradual widening of the perimeter to allow the 21st Marines to wedge a defensive sector between the 3rd and 9th Marines. This action would then put all three Marine infantry regiments on the front lines. Colonel Ames’ 21st Marines passed through the junction of the 3rd and 9th Marines and crossed the Piva River without difficulty. By early afternoon, the two assault battalions (1/21 and 3/21) had reached the designated line, and the attack was held up to await further orders. The approach march had been made without enemy interference, except on the extreme left flank where a reinforced platoon, acting as the contact between the 21st Marines and the 3rd Marines, was hit by a strong Japanese patrol. The Marine platoon managed to repulse this attack with heavy losses to the enemy. Important documents, outlining the Japanese defenses ahead, were obtained from the body of a dead Japanese officer.

By 1425, the 21st Marines had established a new defensive sector, and contact between 3/21 and the 9th Marines had been established. There was, however, no contact between 1/21 and 3/21 along the front

lines. The remaining battalion, 2/21, was then released from operational control by the 3rd Marines, and this unit moved into reserve positions behind 3/21 and 1/21 to block the gap between the battalions.

The enemy resistance in the 3rd Marines’ sector, however, was unexpectedly strong. All three battalions were engaged with the Japanese during the course of the advance. The left battalion, 3/3, crossed the Piva River without trouble and advanced toward a slight rise. As the 3/3 scouts came over the top of this ridge, the Japanese opened fire from reverse slope positions. The scouts were pinned down by this sudden outburst, but after the rest of the battalion moved forward a strong charge over the ridge cleared the area of all Japanese. Before the battalion could consolidate the position, though, enemy 90-mm mortars registered on the slope, and the Marines were forced to seek shelter in the 200 or more foxholes which dotted the area. These enemy emplacements and the steep slope prevented many casualties. The 3rd Battalion decided to halt in this position and a defensive perimeter was set up for the night.

The 2nd Battalion, making a reconnaissance in force in front of the 1/3 positions, bumped into a strong enemy position astride the East-West trail near the east fork of the Piva. About 18 to 20 pillboxes were counted, each of them spitting rifle and machine gun fire. De Zayas’ battalion managed to crack the first line of bunkers after some fighting at close range, but could make no further headway. Company E, attempting to flank the enemy positions to relieve the intense fire directed at Company G, was knocked back by the Japanese defenders. Aware now that the enemy was organized in considerable depth, the battalion commander ordered a withdrawal to allow artillery to soften up the enemy positions.

The retrograde movement was difficult since there were many wounded Marines and the terrain was rugged, but the withdrawal was managed despite the determined efforts by the Japanese to prevent such a disengagement. After de Zayas’ battalion had reentered the lines of 1/3, the Japanese attempted a double envelopment of the position held by the 1st Battalion (now commanded by Major Charles J. Bailey, Jr.). This was a mistake. The enemy followed the obvious routes of approach down the East-West Trail, and his effort perished in front of the machine guns sited along this route by 1/3. Bailey’s battalion then extended to the left toward Cibik Ridge.

The 9th Marines, meanwhile, had crossed the Piva River in the right sector and were now occupying a new line of defense about 1,000 yards east of the river. The new positions extended from the beach to the 21st Marines in the center sector. The 129th Infantry, completing the general advance of the Marine-Army perimeter to Inland Defense Line E, also moved forward another 1,000 yards. The 37th Division unit was also unopposed.

Action along the entire beachhead dwindled on the 22nd of November. The 21st Marines bridged the gap between the two front line battalions by shifting 3/21 about 400 yards to the right to make contact with 1/21. A considerable gap still existed between the 21st Marines and the 3rd Marines. This break in the defensive lines was caused by the fact that the frontage of the Marine positions was greater than anticipated because of map inaccuracies.

The expansion of the perimeter was halted on these lines while a concerted

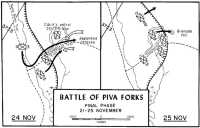

Map 20: Battle of Piva Forks, Final Phase, 21-25 November

attack was planned to push the Japanese out of the strongly entrenched positions ahead. The enemy fortifications, which faced nearly south because of the twists of the trail, would be assaulted from the west to east in a flanking attack. To insure a coordinated advance, the attack was set for 24 November, with the East-West trail as the boundary between the assaulting regiments.

It was now apparent that the main Japanese dispositions had been reached, and intensive preparations for the full-scale assault on the enemy forces were rushed. All available tanks and supporting weapons were moved forward into positions behind the 3rd Marines as fast as the inadequate trail net would permit. Engineers and Seabees worked to extend the road as close to the Piva River forks as possible, erecting hasty bridges across the Piva River despite intense sniper fire and harassment by enemy mortars. Supply sections moved huge quantities of ammunition, rations, and medical supplies forward in a relay system that began with trucks and amtracs and ended with Marines hand-carrying the supplies to the front lines. A medical station was established near the terminus of the road to facilitate evacuation of the wounded. All signs indicated that the 3rd Marines, scheduled to advance on the 24th, would be meeting a strong enemy force.

By the evening of the 22nd, several changes had been made in the sector of the 3rd Marines. The 2nd Raider Battalion, now attached to the 3rd Marines, was ordered to relieve King’s battalion on the small hill which had been taken the day before, and 3/3 then moved to a reserve

bivouac area behind 1/3 and nearly abreast of 2/3. The dispositions of the 3rd Marines at this time resembled a triangle with the apex pointed along the East-West trail toward the Japanese positions. The 1st Battalion was in front, with 3/3 on the left of the trail and 2/3 on the right. Cibik’s force, holding a position in front of the perimeter, was reinforced with a company of raiders and a platoon from the 3rd Marines Weapons Company. By this time, the observation post was defended by more than 200 Marines and bristled with supporting weapons. The Japanese, to reclaim this position, would have to pay a terrible price.

On 23 November, artillery observers moved to the crest of Cibik Ridge to adjust fires in preparation for the attack the next day. The Marines holding the front lines marked their positions with colored smoke grenades, and both artillery and mortars were then registered in the area ahead. The sighting rounds caused some confusion when several explosions occurred within the Marine positions. It was then realized that the Japanese were firing in return and using the same smoke signals for registration on the Marine lines.

Shells from long-range enemy guns were also falling on Torokina strip and an echelon of LSTs unloading near the cape. The observers on Cibik Ridge shifted registration fires toward several likely artillery positions and the enemy fire ceased. The news that the enemy had artillery support for the defense of his positions was disturbing, though. Scouts had estimated that the enemy force, located in the area around the village of Kogubikopai-ai, numbered about 1,200 to 1,500. The addition of artillery support would make the job of reducing this strong position even more difficult.

The attack order for 24 November directed the two battalions, 2/3 and 3/3, to advance abreast along the East-West trail and attack for about 800 yards beyond the east fork of the Piva River. Seven battalions of artillery—four Marine and three Army—would provide support for the attack after an opening concentration of 20 minutes fire on an area about 800 yards square. During the day of 23 November, while the artillery group registered on all probable enemy positions, Bailey’s 1/3 moved every available weapon, including captured Japanese guns, into the front lines. By nightfall, 1/3 had emplaced 44 machine guns across the trail and had registered the concentrations of a dozen 81-mm mortars and 9 60-mm mortars along the zone of action of the attacking battalions.

Early the next morning, the two battalions began moving out of bivouac and up the trail toward the front lines held by 1/3. It was Thanksgiving Day back in the States; but on Bougainville this was just another day of possible death, another day of attack against a hidden, determined enemy. Few Marines gave the holiday any thought—the preparations for this advance during the last two days had built up too much tension for anything but the job ahead. Behind the Marines, in the early dawn mist, trucks and amtracs churned along muddy trails, bringing forward last loads of rations, ammunition, and medical supplies. Tanks, assigned to a secondary role in this attack, clanked toward the front lines to move into support positions.

At 0835, just 25 minutes before the attack hour, the seven battalions of the artillery group opened fire on the Japanese

positions in front of the 3rd Marines. From the opening salvo, the roar of the cannon fire and the sharp blasts of the explosions in the jungle ahead merged into a near-deafening thunder. In the next 20 minutes or so, more than 5,600 shells from 75-mm and 105-mm howitzers hammered into the Japanese positions. The enemy area was jarred and shattered by more than 60 tons of explosives in that short time. At the same time, smoke shells hitting along the hills east of the Torokina River cut down enemy observation into the Marine positions.

As H-Hour approached, Bailey’s battalion, from the base of fire position astride the East-West trail, opened up with close-in mortar concentrations and sustained machine gun fire which shredded the jungle ahead, preventing the Japanese from seeking protection next to the Marine lines. But just before the attack was to jump off, Japanese artillery began a counterbarrage which blasted the Marine lines, pounding the 1/3 positions and the assembly areas of the assault battalions. The extremely accurate fire threatened to force a halt to the attack plans. At this point, the value of Cibik Ridge was brought into full prominence. The forward observer team on the ridge discovered the location of a Japanese firing battery and requested counterbattery fire. There were several anxious moments when communications abruptly failed, but the line break was found and repaired in time.

The enemy guns were located on the forward slope of a small coconut grove area some several thousand yards from the Piva River. As the two Marine officers watched, the return fire from the 155-mm howitzer battery of the 37th Division began to explode near this grove. Fire was adjusted quickly by direct observation, and in a matter of moments the enemy battery had been knocked out of action.9

Even as the last Japanese artillery shells were exploding along the Marine lines, the two assault battalions began forming into attack formation behind the line of departure. At 0900, as the continuous hammering of machine guns, mortars, and artillery slowly dwindled to a stop, the two battalions moved through the 1/3’s lines and advanced.

After the continuous roar of firing and explosions for more than 20 minutes, a strange stillness took over. The only sounds were those of Marines moving through the jungle. The neutralization of the enemy positions within the beaten zone of the artillery preparation had been complete. The first few hundred yards of the enemy positions were carried without difficulty in the incredible stillness, the Marines picking their way cautiously through the shattered and cratered jungle. Blasted and torn bodies of dead Japanese gave mute evidence of the impact of massed artillery fires. Enemy snipers, lashed into positions in tree tops, draped from shattered branches.

This lull in the battle noise was only temporary. Gradually, as the stunned survivors of the concentrated bombardment

began to fight back, the enemy resistance swelled from a few scattered rifle shots into a furious, fanatical defense. Japanese troops from reserve bivouac areas outside the beaten zone were rushed into position and opened fire on the advancing Marines. Enemy artillery bursts blasted along the line, traversing the front of the advancing Marines. Extremely accurate 90-mm mortar fire rocked the attacking companies.

Enemy fire was particularly heavy in the zone of 2/3 on the right of the East-West trail, and de Zaya’s battalion, after moving about 250 yards, reported 70 casualties. A small stream near the trail meandered back and forth across the zone of advance, and the attacking Marines were forced to cross the stream eight times during the morning’s movement. At least three enemy pillboxes were located in triangular formation in each bend of the stream, and each of these emplacements had to be isolated and destroyed. A number of engineers equipped with flame throwers moved along with the assault companies, and these weapons were used effectively on most bunkers. The Japanese, fully aware of the death-dealing capabilities of the flame throwers, directed most of their fire toward these weapons. Many engineers were killed trying to get close enough to enemy emplacements to direct the flame into the embrasures.

The attack by King’s battalion (3/3) on the left of the East-West trail encountered less resistance, and the battalion was able to continue its advance without pause. Many dazed and shocked survivors of the bombardment were killed by the attacking Marines before the Japanese could recover from the effects of the artillery fire. But by the time the battalion had moved nearly 500 yards from the line of departure, the enemy forces had managed to reorganize and launch a desperate counterattack which King’s men met in full stride. Without stopping, 3/3 drove straight through the enemy flanking attempt in a violent hand-to-hand and tree-to-tree struggle that completely destroyed the Japanese force.

By 1200, after three full hours of furious fighting, the two battalions had reached the initial objectives, and the attack was held up for a brief time for reorganization and to reestablish contact between units. Following a short rest, the Marines started forward again toward the final objective some 350-400 yards farther on. Meanwhile, artillery again pounded ahead of the Marine forces and mortars were moved forward. The final attack was supported by 81-mm mortars; but as the advance began again, enemy counter-mortar fire rained on the Marines. The attack was continued under this exchange of supporting and defensive fires.

King’s battalion was hit hard once more, but managed to keep going. Enemy machine gun and rifle fire from positions on high ground bordering a swampy area raked through the attacking Marines, forcing them to seek cover in the knee deep mud and slime. Company L, on the extreme left, was hit hardest. Reinforced quickly with a platoon from the reserve unit, Company K, the company managed to fight its way through heavy enemy fire to the foot of a small knoll. Company I, with the battalion command group attached, came up to help. Together, the two companies staged a final rush and captured the rising ground. After clearing this small elevation of all enemy, the battalion

organized a perimeter defense and waited for 2/3 to come up alongside.

The 2nd Battalion, moving toward the final objective, was slowed by strong enemy reinforcements as it neared its goal. Quickly requesting 60-mm and 81-mm mortar concentrations, the 2nd Battalion overcame the enemy opposition and lunged forward. The final stand by the Japanese on the objective was desperate and determined, but as the Marines struggled ahead, the resistance dwindled and died. The 2nd Battalion then mopped up and went into a perimeter defense to wait out the night. Behind the two front battalions, however, the battle continued well into the night as isolated enemy riflemen and machine gunners that had been overrun attempted to ambush and kill ammunition carriers and stretcher bearers.

During the day, the corps artillery group, providing support for the Marine attack, fired a total of 52 general support missions in addition to the opening bombardment. Nine other close-in missions were fired as the 37th Division also moved its perimeter forward. In all, during the attack on 24 November, the artillery group fired 4,131 rounds of 75-mm, 2,534 rounds of 105-mm, and 688 rounds of 155-mm ammunition.

The casualties during this attack also reflected the intensity of the combat. After the conclusion of the advance by the Marines, at least 1,071 dead bodies of Japanese were counted. The Marine casualties were 115 dead and wounded.

For some Marines, the day was Thanksgiving Day after all. A large shipment of turkeys was received at the beachhead, and, unable to store the birds, the division cooks roasted the entire shipment and packed the turkeys for distribution to front line units.10 Not every isolated defensive position was reached, but most of the Marines had a piece of turkey to remind them of the day.

Grenade Hill11

The following morning, 25 November, the 3rd Marines remained on the newly-taken ground, while a number of changes were made in the lineup along the perimeter. Two days earlier, General Turnage had directed that the 3rd Marines and the 9th Marines exchange sectors as soon as possible. This move would allow Colonel McHenry’s 3rd Marines, by now badly depleted by battle casualties, sickness, and exhaustion, to take over a relatively quiet sector while the 9th Marines returned to action.

The changes had been started on the 24th while the 3rd Marines were engaged in the battle for Piva Forks. The 1st Battalion of the 9th Marines, now commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Carey A. Randall, was in regimental reserve positions behind 2/9 and 3/9 on the right flank when alerted by a warning order that the battalion would move on 30-minute’s notice.

Late in the afternoon, Randall’s battalion was ordered to move north along the Piva River to report to Colonel McHenry’s regiment for operational control. Shortly before dark, Randall reported to McHenry and was directed to an assembly area. The battalion was to be prepared for relief of the front lines as soon after daybreak as possible. The 2nd Battalion of the raider regiment, with two companies of the 3rd Raiders attached, was also ordered to move up behind the 3rd Marines for commitment to action.

On the morning of the 25th, as the 2nd Raiders and 1/9 moved toward the front lines to extend the perimeter, a number of other changes were directed. De Zayas’ 2/3, south of the East-West trail, extended its right flank to the southeast to make contact with the 21st Marines. King’s battalion, 3/3, organized defensive positions on the left of the East-West trail to make contact with Cibik Ridge where a reinforced company was holding. As the front lines were straightened, 1/3 was withdrawn from action and 3/9 moved into reserve positions behind the 3rd Marines. To substitute for the loss of 1/9 and 3/9 to the left sector, a newly arrived battalion of the 37th Division was attached to the 9th Marines. This unit, the 1st Battalion of the 145th Infantry, was placed in reserve positions in the extreme right sector near Piva Village.

Meanwhile, as these changes were made, the 2nd Raiders and 1/9 moved east along the East-West trail to begin the day’s attack. Randall’s 1/9 was to move up Cibik Ridge and then attack almost directly east on a front of 400 yards to extend the left flank of 3/3. The 2nd Raiders were to attack on the left flank of 1/9 on a front of about 800 yards. The objective, an area of high ground north of the East-West trail, was about 800 yards distant.

Randall’s battalion, guided by a patrol from Cibik Ridge, proceeded single file to the crest. There the Marines could see the attack objective ahead. At 1000, after another crushing 10-minute artillery preparation, the attack was started straight down the opposite side of Cibik Ridge. The assault companies lined up with A on the left and C on the right. Company B was to follow on order. Attached machine guns supported each company, and a heavy mortar barrage from Cibik Ridge pounded ahead as the Marines attacked. At the foot of the ridge, both attacking companies were held up by extremely heavy machine gun fire from concealed positions on a small knoll just ahead. The fight for this knob of ground continued the rest of the day.

The 2nd Raiders, meanwhile, had advanced against sporadic resistance. The attack was held up several times by enemy groups; but, as the raiders prepared to assault the defenses, the enemy suddenly gave ground to retire to new positions. By afternoon, Major Washburn’s battalion had occupied the hill mass dominating the East-West trail and established a strong perimeter defense on the objective to wait for the battalion from the 9th Marines to come up on line.

Randall’s battalion, however, had its hands full. Both attack companies had committed their reserve platoons to the assault of the small knoll facing them without making headway. The enemy was well dug-in with a complete, all-around defense. Marines estimated that the small hill was held by at least 70 Japanese with 4 heavy (13-mm) machine guns and about 12 Nambu (6.5-mm) machine guns. In addition, the Japanese apparently had plenty

of grenades, since a continual rain of explosives was hurled from the enemy positions. The Marines, unable to advance against this formidable strongpoint, dubbed the knoll “Grenade Hill.”

Many attempts to envelop this position were repulsed. At some points, the Marine attackers were only five yards from the enemy emplacements, engaged in a hot exchange of small-arms fire and grenades, but unable to carry the last few yards. The fight was conducted at such close quarters that the mortars on Cibik Ridge could not be registered on the enemy position. Many of the dugouts along the side of the hill were destroyed by the Marine attacks, but the crown of the hill was never carried. One platoon from Company A, circling the knoll to the left, managed to fight up a small trail into the position. Fierce enemy fire forced the Marines back before the crest of the ridge was reached. Fourteen Japanese were killed by the Marine platoon in this attempt to take the hill.

By midafternoon, Company B was ordered from Cibik Ridge to plug the gap between the 1/9 attack and the positions of 3/3 on the right. Company B moved down the slope of Cibik Ridge toward the East-West trail south of Grenade Hill and continued east on the trail for several hundred yards in an attempt to locate the left flank of the 3rd Marines. Shortly before dusk, the company abruptly ran into a Japanese force. After an intense but short fire fight, the Marine company decided that the Japanese position on higher ground was too strong to overrun and broke off contact. The company then withdrew to a defensible position closer to Cibik Ridge. The Japanese made a similar decision and also withdrew. Company B, out of touch with 1/9 and unable to locate the left flank of 3/3 before dark, organized a defense position across the trail and settled down to wait for morning.

Meanwhile, the fight for Grenade Hill had dwindled and stopped. The two companies of 1/9, unable to capture the hill, dug in around the base of the knob to wait for another day. The 2nd Raiders, on the objective, remained in front of the lines in a tight defensive ring.

The next morning, 26 November, scouts from 1/9 reported that the Japanese had quietly withdrawn from Grenade Hill during the night and the small knoll was abandoned. The two assault companies rushed for the hill at once, taking over the enemy positions along the crown of the knoll. The small knob of ground, about 60 feet across at the base and hardly more than 20 feet high, was dotted with a number of well-constructed and concealed rifle pits and bunkers. Each bunker was large enough for at least three enemy soldiers. Only 32 dead Japanese were found on the hill. At 1015, the attack was pushed forward again and contact was made with Company B. This company, during the morning, had linked up with the left flank of the 3rd Marines, thereby establishing contact along the line. Company B then joined with 1/9 to complete the move to the final objective. By nightfall, the ridgeline blocking the East-West trail was in Marine hands.

During the attacks of 25-26 November, the Marines lost 5 killed and 42 wounded. At least 32 Japanese had been killed in the assaults on Grenade Hill, and there had undoubtedly been additional casualties in the attacks in other areas. The number of enemy killed during the period 18-26 November in the 3rd Division sector was at least 1,196, although the total number of

casualties must have been considerably higher than that figure.12

The fight for expansion of the beachhead in this area was recorded as the Battle of Piva Forks, and marked the temporary end of serious enemy opposition to the occupation and development of the Cape Torokina area. The only high ground from which the enemy could threaten or harass the beachhead was now held by IMAC forces, and possession of the commanding terrain facing the Piva River gave the Marine regiments an advantage in defending that sector.

After the objective of 26 November had been secured, the remainder of the directed reliefs were completed. The 3rd Battalion of the 9th Marines relieved 3/3 in the front lines, and this battalion then became the reserve unit behind 1/9 and 3/9. Control of 1/3 was then shifted to the 9th Marines, and at 1600 on the afternoon of the 26th, the 3rd Marines and 9th Marines exchanged commands in the left and right subsectors. The 21st Marines, maintaining positions in the center subsector, moved forward about 500 yards after the attack on Grenade Hill. The IMAC dispositions at the conclusion of the fighting on 26 November had the 148th and 129th Infantry Regiments on line in the 37th Division sector, and the 9th Marines, the 21st Marines, and the 3rd Marines on line, left to right, in the Marine sector.

For the 3rd Marines, this last move to the right sector completed a full cycle of the beachhead which was begun on D-Day. Following the landing, the regiment moved toward the Koromokina River, then traveled inland through the jungle and swamps to the Piva Forks area. Finally, after 27 days of jungle fighting, the regiment was back near Cape Torokina within the limits of patrols of the first two days ashore.

In the right sector, the exhausted infantry battalions of the 3rd Marines were given a respite by the formation of a composite battalion from among the Regimental Weapons Company, the Scout Company, several headquarters companies, and supporting service troops. This makeshift battalion took over a position along the Marine lines on the 28th of November and maintained the defense until early in December so that Colonel McHenry’s 3rd Marines could reorganize and rest. The Army battalion, 1/145, assigned to this sector was also placed in frontline defenses under the operational control of the 3rd Marines and aggressively patrolled past the Torokina River seeking the enemy.

The Japanese, however, evidently intended to do no more than keep this area under observation. Other than a few brushes with enemy outposts, the 3rd Marines were out of contact with the Japanese for the remainder of the campaign. The problem, as before, was mainly one of maintaining and supplying the Marine fighting units in the midst of swamplands.

On the 28th of November, General Geiger ordered that the IMAC perimeter in the center and left subsectors be moved forward to Inland Defense Line F, and, after this line was occupied, artillery was displaced forward to defend the area seized and to support the last push to the final beachhead line.13

The area fronting the Marine perimeter at this time varied from mountainous terrain to deep swamps and dense jungle.

Numa Numa trail position in the swamp below Grenade Hill held by Marines of Company E, 2/21. (USMC 69394)

Marine wounded are carried down a steaming jungle trail from Hill 1000 during the fighting in early December. (USMC 71380)

The 9th Marines, on the right flank of the 37th Division, reported rugged terrain in this subsector with many ridges and deep gorges cut by waterfalls and streams: The 21st and 3rd Marines, however, still faced the task of holding areas in the midst of swamps. These, the Marines reported, were not impassable, but it was certain that large forces of enemy could not advance through these swamps without detection by one of the many patrols which roved back and forth between units during the day. At night, small groups moved into the swamps as listening posts.

Every possible battle position, however, was wired and mined. Gaps in the frontline defense were covered by automatic weapons. The Japanese, however, never attempted an infiltration during this time, and only scattered groups of enemy were encountered. These were evidently only scouts who were trying to keep the Marines’ progress under surveillance.

The Marines continued to gain combat experience. Two rules of jungle warfare were found invaluable during this period. The first rule was to avoid using the same trail twice in a row—because the second time the trail would be ambushed. The second rule was to avoid heckling a Japanese outpost twice unless prepared to fight a full-scale battle on the second go-around. Inevitably, in these brushes with the Japanese, the second fight was more vicious and determined than the first. While the enemy did not actively seek out the Marine units for battle, the small outpost engagements convinced the Marines that the enemy was still in the area in force and prepared to fight any further expansion of the beachhead.