Chapter 6: End of a Mission

The Koiari Raid1

Throughout the expansion of the beachhead past the Piva River forks, the possibility of a major counterattack by the Japanese along the right flank was a constant threat. To short-circuit possible enemy plans to carry out a full-scale reinforcement effort along this route, a raid on Japanese lines in the southern part of Empress Augusta Bay was proposed. This would disrupt enemy communications, destroy installations and supplies, and obtain information about any troop movements towards the beachhead. The foray was aimed at reported Japanese installations near Koiari, about 10 miles down the coast from Cape Torokina.

The unit selected for this operation was the 1st Parachute Battalion (Major Richard Fagan), which had arrived on Bougainville from Vella Lavella on the 23rd of November. Fagan’s battalion was to operate much in the manner of Krulak’s group on Choiseul. The parachute battalion was to harass enemy units as far inland as the East-West trail but was to avoid a decisive engagement with major Japanese forces. A boat would rendezvous each night with the raiding unit if communications failed. The orders for withdrawal would be given by IMAC headquarters.2

The raid was originally scheduled for the morning of 28 November so that escorting destroyers of a shipping echelon could provide naval gunfire support if needed. A trial landing on the selected beach, about 3,000 yards north of Koiari, was made after dark on the 27th by one boat, whose crew then returned to report that there was no evidence of enemy in the area. Because of delay in the actual embarkation of the parachute battalion, however, the entire operation was postponed until the 29th.

Destroyer support would no longer be available, but this lack was not disturbing. One 155-mm howitzer battery from the 37th Division was in position near Cape Torokina to support the parachute battalion with long-range fire, and air support could be expected during the day. Two LCI gunboats, which had proved successful during the Treasurys operation, were also available. General Geiger, taking account of the fire support at hand, decided that one day’s postponement would not jeopardize the operation and another reconnaissance boat was sent to the selected beach late on the evening of 28 November. The second report was similar to the first: no enemy sighted. In view of later developments,

it is doubtful that either of the reconnaissance boats landed at the designated beach.

Fagan’s battalion, with Company M of the 3rd Raider Battalion and a forward observer team from the 12th Marines attached, embarked on board LCMs and LCVPs at Cape Torokina early on the morning of 29 November. One hour later, at 0400, the boats moved in toward the Koiari beach and the Marines were landed virtually in the middle of a Japanese supply dump. The surprise was mutual. A Japanese officer, armed only with a sword, and apparently expecting Japanese boats, greeted the first Marines ashore. His demise and the realization of his mistake were almost simultaneous. The Marines, now committed to establishing a beachhead in the midst of an enemy camp, dug in as quickly as possible to develop the situation.

Before the Japanese recovered from the sudden shock of American forces landing in the middle of the supply dump, the parachute battalion had pushed out a perimeter which extended roughly about 350 yards along the beach and about 180 yards inland. The force was split—the raider company and the headquarters company of the parachute battalion had landed about 1000 yards below the main force and outside the dump area. The Japanese reaction, when it came, was a furious hail of 90-mm mortar shells and grenades from “knee mortars.” The entire beachhead was raked by continual machine gun and rifle fire. Periodically the Japanese mounted a determined rush against one flank or the other. The Marines, taking cover in hastily dug slit-trenches in the sand, returned the fire as best they could. Casualties mounted alarmingly.

The battalion commander, meanwhile, radioed IMAC headquarters of the parachutists’ plight and requested that the unit be withdrawn since accomplishment of the mission was obviously impossible and the slow annihilation of the battalion extremely likely. General Geiger immediately took steps to set up a rescue attempt, but unfortunately the return radio transmission was never received by Fagan. By midmorning, Fagan’s radio failed and although it would transmit, it could not receive incoming messages. Contact with IMAC was later made over the artillery net to the forward observer team. At 0930, the beachhead was strengthened by the arrival of the two companies which had been separated. These Marines had fought their way along the shoreline to reach the main party, losing 13 men during the march.

As time passed, Fagan became more convinced that his battalion was in a tighter spot than IMAC headquarters realized. The battalion commander estimated that the Japanese force numbered about 1,200 men, with better positions than the Marines for continued fighting. When the first rescue attempt by the landing craft was beaten back by an intense artillery concentration along the shoreline, the situation looked even more grim. When a second rescue attempt was also repulsed by the Japanese artillery, the Marines resigned themselves to a long fight.

Late in the afternoon, when enemy trucks were heard approaching the perimeter from the south, the parachutists guessed that an all-out attack that night or early the next morning would attempt to wipe out the Marine beachhead. Taking stock of the situation—their backs to the sea, nearly out of ammunition, without

close support weapons—the Marine parachutists reluctantly but realistically concluded that the enemy’s chances for success were quite good.

During the day, 155-mm guns of the 3rd Defense Battalion at Cape Torokina registered along the forward edge of the parachutists’ perimeter, keeping the enemy from making a sustained effort from that direction. IMAC, in the meantime, sent an emergency message to the task force escorting transports back to Guadalcanal, and three of the screening destroyers immediately reversed course and steamed at flank speed for Bougainville. The three support ships—the Fullam, Lansdowne, and Lardner and one of the LCI gunboats arrived shortly before 1800. The Fullam, first to arrive, opened fire immediately under the direction of two gunfire officers from IMAC who had raced for the beleaguered beachhead in a PT boat.

There was little daylight left for shooting on point targets by the time the destroyers arrived. Unable to see the beach, they stationed themselves by radar navigation and opened up with unobserved fires which the gunfire officers adjusted by sound. The ships fired directly to the flanks of the Marine beachhead, while the 155-mm guns at Cape Torokina fired parallel to the beach. The effect was a three-sided box which threw a protective wall of fire around the Marine position. Behind this shield, the rescue boats made a dash for the beach. The Marine battalion, which had been alerted for the evacuation through the artillery radio net, was waiting patiently despite the fact that its last three radio messages had indicated that it was out of ammunition.

For some reason—probably because the Japanese were busy seeking cover from naval gunfire—there was no return enemy fire. As the rescue boats beached, the Marines slowly retired toward the shore. There was no stampede, no panic. The withdrawal was orderly and deliberate. After waiting to insure that all Marines were off the perimeter, the battalion commander gave the signal to clear the beach and at 2040 the last boat pulled away without drawing a single enemy shot. The artillery battery and the gunfire support ships then worked over the entire beach, hoping to destroy the Japanese force by random fires.

The attempt to raid the Japanese system of communications and supply along the Bougainville coast ended in a dismal failure. Although the Marines had landed in an area where great destruction could have been accomplished, they were never able to do more than hug the shoreline and attempt to defend their meager toehold with dwindling ammunition until rescued. In the pitch darkness at the time of evacuation, much of the Marine equipment was lost. Although the withdrawal was orderly, some crew-served weapons, rifles, and packs were left behind. Enemy supplies destroyed would have to be credited to the bombardment by Allied artillery and destroyers after the evacuation. The Marines estimated that the Japanese had lost about 291 men, about one-half of whom were probably killed and the others wounded. The Marine parachute battalion, which landed a total of 24 officers and 505 enlisted men plus 4 officers and 81 enlisted men from the 3rd Raiders, listed casualties as 15 killed or died of wounds, 99 wounded, and 7 missing.3

Hellzapoppin Ridge and Hill 600A4

After the move to Inland Defense Line F, corps headquarters kept its eyes on a hill mass some 2,000 yards to the front which dominated the area between the Piva and Torokina Rivers. These hills, if held by the Japanese, would give them observation of the entire Cape Torokina area and a favorable position from which to launch an attack against the IMAC beachhead. Geiger’s headquarters felt these hills were a continual threat to the perimeter.

On the other hand, Marine occupation of the hills would provide a strong natural defensive position blocking the East-West trail at its Torokina River crossing and would greatly strengthen the final Inland Defense Line. That line, which included the hill mass, was to have been occupied by 30 November, but the supply problems through the swamps and the enemy action had caused an unavoidable delay. Despite the added logistical difficulties which occupation of this hill mass would involve, corps headquarters directed the 21st Marines to maintain a combat outpost on one of the hills until the perimeter could be extended to include this area.

On 27 November, a patrol of 1 officer and 21 men from Colonel Ames’ regiment moved to Hill 600 where observation could be maintained over the other two hills and the Torokina River. Hill 600, just south of the East-West trail, was bordered on the left by a higher, longer ridge about 1,000 feet high. A smaller hill, about 500 feet high, was farther south.

As a preliminary to eventual occupation of the hills by IMAC forces, the 1st Marine Parachute Regiment, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Robert H. Williams, was moved from reserve positions on Vella Lavella on 3 December. Two days later, this unit—actually just the regimental headquarters, the weapons company, and the 3rd Parachute Battalion—moved toward the largest of the three hills, Hill 1000. The parachute regiment made a forced march with a half-unit of fire and only three days’ rations. This shortage of food was later partially solved by an airdrop on the regiment’s position. Williams’ regiment pushed forward along the East-West trail almost to the Torokina River before turning to the north to start the climb of the ridgeline toward Hill 1000.

By the end of 5 December, the 1st Parachute Regiment with units of the 3rd, 9th, and 21st Marines in support, had established a general outpost line stretching from Hill 1000 to the junction of the East-West trail at the Torokina River. A Provisional Parachute Battalion, under Major George R. Stallings, was formed by Williams from regimental headquarters and Company I to occupy the left sector of his defenses.5 Williams’ command,

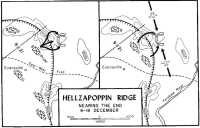

Map 21: Hellzapoppin Ridge, Nearing the End, 6-18 December

with about 900 men, was strung over a thinly held line about 3,000 yards in length. Meanwhile, the 21st Marines outpost on Hill 600 was reinforced. A full rifle company with a machine gun platoon and the IMAC experimental rocket platoon attached was moved forward to bolster the Marine defense on the two hills blocking the East-West trail.

The move to this hill mass overlooking the Torokina River was made at about the time that the Japanse evidenced a strong interest in these positions. During the period 27 November to 4 December, the enemy activity was confined to minor contacts along the perimeter with the Japanese using mostly long-range artillery fire to make their continued presence known. On 29 November, the Cape Torokina airfield site was hit by a number of 15-cm howitzer shells from extreme range. On 3 December, the Japanese attempted to shell the beachhead once more. This time the artillery was emplaced on a forward slope, and a fierce counterbattery fire from three battalions of 75-mm howitzers, one battalion of 105-mm howitzers, and one battery of 155-mm guns quickly smashed the Japanese position. The artillery spotting problem was further aided on 4 December by the delivery of two light planes. These slow-moving aircraft increased the effectiveness of artillery fire by allowing observers to spot targets of opportunity and request and adjust fires. The scout bombers which had been used as spotting planes flew too fast and had too many blind spots to be good observation planes.

The first enemy contact of any consequence since Grenade Hill came in the sector of the 9th Marines on 5 December. Colonel Craig’s regiment had been ordered

to expand the perimeter to make contact with the parachute regiment on Hill 1000, and, as a small patrol from 2/9 moved out, it was ambushed by about 10 Japanese. The Marines lost two killed and two wounded in the first exchange. The Japanese then withdrew. The following day a 40-man patrol from the 9th Marines aggressively scouted ahead of the regiment but did not encounter any enemy forces. This day, the entire beachhead took another jump forward as advance units of the three regiments pushed inland. On the right flank, 3/3 advanced from positions which had been occupied since 21 November and put a patrol on Hill 500 south of the strong 21st Marines outpost on Hill 600. This position was then strengthened by the extension of an amphibian tractor trail from the swamps to Hill 600, assuring an adequate supply route. The 9th Marines, on the far left, moved up to make contact with the Marines holding Hill 1000.

A general line of defensive positions now stretched from the area north of Hill 1000 along this ridge to the East-West trail and then to the two smaller hills, 600 and 500, south of the trail. With the extension of the supply lines, a growing supply dump called Evansville was established to the rear of Hill 600 near the East-West trail to insure supply of the final defensive line. The advance to Inland Defense Line H came on a day when the entire island was rocked by a violent earthquake. Earthworks and trenches were crumbled and gigantic trees swayed as the ground trembled and rolled. Persons standing were thrown to the ground by the force of the quake. Other earth tremors were recorded later, but none achieved the force of the quake of 6 December.

Movement to the final defense line came as minor patrol clashes were reported along the entire perimeter. On 7 December, the Provisional Parachute Battalion discovered abandoned positions on a 650-foot ridge which extended east from Hill 1000 toward the Torokina River, much in the manner that Grenade Hill was an offshoot of Cibik Ridge.6 Patrols returned to report that a number of well dug-in and concealed emplacements had been found on the ridge, and Williams made plans to occupy this area with part of his force the next morning. A patrol from the Provisional Parachute Battalion started down the spur on the 8th of December but was driven back by unexpected enemy fire. The Japanese, repeating a favorite maneuver, had returned to occupy the positions during the night.

The patrol reorganized and made a second attempt to seize the enemy position. No headway was made during a sharp exchange of fire. After eight Marines had been wounded, the patrol returned to the front lines. On the morning of 9 December, three patrols of the 3rd Parachute Battalion converged on the spur; each encountered light resistance and reported that the enemy broke contact and withdrew. Major Vance ordered Company K to move forward and secure the area. The advancing Marines soon discovered that, “far from withdrawing, the Japs were still there and in considerable strength.”7

Company K managed to penetrate the Japanese positions, but continued heavy casualties forced a withdrawal before the entire ridge could be captured. During this attack, the enemy fire showed few signs of slackening. Vance then ordered

Company L to outflank the Japanese lines, requesting the Provisional Battalion to support with Company I on the left flank. “Neither of these two units could make headway against the almost sheer sides of the ridge and the heavy fire of the enemy.”8 Several patrols from Company I were ambushed by Japanese in strong emplacements, and, during the confused close-range battle, one light machinegun squad became separated from the rest of the patrol. This squad did not return with the rest of the company, and an immediate search by a strong patrol failed to locate the missing men. Three of the Marines later returned to Hill 1000, but the rest of the squad were carried as casualties.

Despite a number of sharp attacks by the parachute regiment, the enemy position remained as strong as before. The Marines, eyeing the Japanese bastion, called for reinforcements to plug the weak spots caused by the casualties in the overextended lines, and two rifle companies from adjacent units were rushed to Hill 1000. Company C, 1/21, at Evansville, was attached to Vance’s unit and moved into the 3rd Parachute Battalion’s positions bringing much needed ammunition and supplies. At the same time, Company B, 1/9 advanced to cover the gap on the left between 3/9 and the lines on Hill 1000.

That afternoon, the parachute regiment was hit suddenly by a strong Japanese counterattack aimed at the center of the Marine positions on Hill 1000. An estimated reinforced company made the charge, but an artillery concentration centered on the saddle between Hill 1000 and the enemy-held spur broke the back of the Japanese rush. The quick support by 105-mm and 75-mm howitzers scattered the Japanese soldiers and ended the attack. The Marines, though, had 12 men killed and 26 wounded in the brief struggle.

Evacuation of wounded from this battle area was particularly difficult. Only two trails led to the top of the hill—one a hazardous crawl up a steep slope, and the other a wider jeep trail leading toward the Torokina River. Torrential rains made both virtually impassable. At least 12 men were required to manhandle each stretcher case to an aid station set up about half-way down the rear slope. There, blood plasma and emergency care were given the wounded before they were carried to an amtrac trail at the foot of the hill. The wounded men were then moved across the swamps to roads where jeep ambulances were waiting.9

On the morning of 10 December, all units completed the advance to the final defense line along the general line of Hill 1000 to Hill 500, and the 1st Battalion of the 21st Marines moved forward under enemy mortar fire to take over responsibility for the defense of Hill 1000. There was no enemy action in the sectors of the 9th and 3rd Marines on either flank. At 0900, Lieutenant Colonel Williams met the commanders of 1/9 and 1/21 at his command post on Hill 1000, and the details of the relief of the 1st Parachute Regiment by 1/21 and of contact with 1/9 were worked out. There was still action by the enemy, though. A small Marine patrol scouting ahead of the lines to pick up the bodies of dead Marines was fired upon by an enemy force. The Marines drew back and called for an artillery concentration on the area before continuing the patrol. This time

there was only sporadic sniper fire. That afternoon the scattered elements of the parachute regiment moved off Hill 1000, leaving the unfinished business of the enemy stronghold and the difficulties of supply and evacuation to 1/21 and 1/9. The parachute troops, obviously ill-equipped and understrength for such sustained combat, moved into reserve positions behind the IMAC perimeter.

The strong Japanese position on the spur extending east from the heights of Hill 1000 resisted all efforts by the Marines for the next six days. The bitter fighting on this small ridge, which did not even show on the terrain maps provided by IMAC, earned for this stronghold the name of “Hellzapoppin Ridge.” Although Marines sometimes called the enemy position “Fry’s Nose” for the commander of 1/21, Lieutenant Colonel Fry, or “Snuffy’s Nose,” for Colonel Ames, the 21st Marines’ commander, the name of Hellzapoppin Ridge is more indicative of the fierce combat that marked the attempts to capture this spur.

This position, abandoned at the time, was first discovered on 7 December when an enemy operations map was picked up and interpreted. This document indicated that the ridge positions were those of a reinforced company from the Japanese 23rd Infantry. Enemy strength was estimated at about 235 men, but, beyond this, the Marines had no further information on the area which the enemy so stoutly defended. The ridge was about 300 yards long with steep slopes leading to a narrow crest some 40 yards wide. Combat patrols sought to uncover more information about this natural fortress, but the enemy resisted every attempt. All companies of 1/21 launched attacks against this position, but the enemy’s fierce fire drove them back. The Japanese appeared to be well dug in, with overhead cover, in a carefully prepared all-around defense.

Unable to define the limits of the Japanese position, the Marines were unable to bring any supporting weapons except 60-mm and 81-mm mortars to bear on the emplacements. The 60-mm mortars proved too light to open holes for the Marine attacks, and the heavier mortars also appeared to have little effect on the enemy positions. During the first stages of the repeated attacks on Hellzapoppin Ridge, and until the final assault on 18 December, artillery fire was also ineffective. Because the ridge was on the reverse slope of Hill 1000, the artillery batteries had trouble adjusting the angle of fire to hit the spur. The huge trees lining the ridge caused tree bursts, with no effect on the enemy bunkers. The enemy fortress, effectively defiladed by most of Hill 1000, was relatively immune to shelling.

At this time the Marine artillery firing positions were near the bomber airstrip in the vicinity of the Coconut Grove. The direction of fire was almost due east. This location, however, resulted in many “overs” on the enemy position or tree bursts in the jungle along the ridge of Hill 1000 where the front lines of 1/21 were located. Some casualties to Marine personnel were taken during attempts to bring the fire to bear on the enemy fortifications.

On the 13th of December, after repeated attempts to knock the Japanese off Hellzapoppin Ridge by artillery fire had failed, a request for direct air support was made to ComAirNorSols by General Geiger. The IMAC commander requested that the three scout bombers and three torpedo bombers which had just landed at the

newly completed airstrip at Torokina be used that afternoon. The six Marine planes, loaded with 100-pound bombs, made a run on the enemy position just at dusk after the target had been marked by smoke shells from 81-mm mortars. Four planes managed to hit the target area; but the fifth plane dropped its bombs well behind the Marine front line about 600 yards north of the enemy ridge. The explosions killed two Marines and wounded five. The sixth plane returned to Torokina without completing the mission. The Marines, somewhat dubiously, requested another strike for the next day.

For this mission, 17 torpedo bombers from VMTB-232 landed at Torokina airfield for a prestrike briefing. The locations of the Marine lines and the target area were described for the pilots before the planes took off again. This time the Marine lines were marked with colored smoke grenades and the target area with white smoke. The results were considerably better. The planes made the strike in column formation parallel to the front lines. About 90 percent of the bombs landed in the target area.

Another strike the following day, 15 December, was conducted in the same manner. Pilots of 18 TBFs (VMTB-134) landed at Torokina for an extensive briefing by the strike operations officer and a ground troop commander who then led the strike in an SBD. Smoke shells again marked the front lines and the target area, and the torpedo bombers hit the ridge with another successful bombing run. On the 18th of December, two final strikes completed the softening process on the enemy-held positions. Six planes from VMTB-134, each with a dozen 100-pound bombs, landed at Torokina once more for briefing before heading for the target. Each mission was led by the AirSols operations officer, Lieutenant Colonel William K. Pottinger, with the 21st Marines Executive Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Arthur H. Butler, as observer. The first strike was completed with all bombs reported landing in the target area. Later, five more TBFs made a second strike, this time dropping 36 bombs. The second strike was also guided to the target by the lead plane. At the end of this mission, the five planes continued to make strafing runs on the target and executed dummy bombing runs to hold the enemy defenders in place while the 21st Marines attacked and seized the ridge.

Prior to the two air attacks on the 18th, the I Marine Amphibious Corps and the 21st Marines made extensive preparations for the final assault on Hellzapoppin Ridge. A battery of 155-mm howitzers from the 37th Division was moved by landing craft (LCMs) to new firing positions near the mouth of the Torokina River. From this position the battery could fire north along the river valley and put shells on the south side and crest of the ridge without endangering the Marine lines. The 155-mm howitzers, which were moved into these temporary firing positions early on the morning of the 18th, opened fire at about 1000. Smoke shells were used for registration shots before the final concentrations were fired. The battery fired about 190 rounds in the next hour, hitting the ridge repeatedly although there was some initial difficulty in adjusting the fire to get hits along the crest of the knife-like ridge. The artillery shells cleared much of the brush and smaller jungle growth off the ridge, exposing the target to the two air strikes which followed the artillery fire.

Shortly after the final air attack,10 units of 1/21 and 3/21 (committed to action from the regimental reserve) moved off Hill 1000 and over Hellzapoppin Ridge in a coordinated double envelopment. The air attacks and the direct artillery fire had done the job. The blasted and shredded area revealed many dead Japanese. The stunned survivors who made a token resistance were quickly eliminated. After more than six days of repeated attacks on this defensive stronghold, Hellzapoppin Ridge was captured, and the enemy force cleared from the many concealed and emplaced bunkers. The victory cost the 21st Marines 12 killed and 23 wounded. More than 50 Japanese bodies were found in the area. The remainder of the enemy defenders had apparently fled the area.

The next three days were devoted to the extension of the perimeter to include this natural fortress and to improvement of the final defensive line. There was no enemy contact until the morning of 21 December when a reconnaissance patrol reported that about 14-18 enemy soldiers had been discovered on a hill near the Torokina River. A combat patrol from the 21st Marines immediately moved out to drive the Japanese from this hill, 600-A. The Marines lost one killed and one wounded in a short action that ended in a repulse for the attackers. Directed to put an outpost on Hill 600-A, a platoon from 3/21 (Lieutenant Colonel Archie V. Gerard) started for the hill early on the 22nd of December, but once more the Japanese had occupied a position in strength during the night. As the Marines reached the crown of Hill 600-A, a blast of small-arms fire from entrenched enemy forced them back down the hill. Company I of Gerard’s battalion then started forward to reinforce the platoon.

A double envelopment was attempted by Company I, but Japanese defenses on the reverse slope of Hill 600-A stopped that maneuver and pinned the attackers into an area between the enemy lines and the Marine base of fire. Company I, under heavy rifle and machine gun fire, wriggled out of this predicament and withdrew to request artillery support.

Another attack the next day, 23 December, by Company K of Gerard’s battalion ended up much in the same manner. The company, reinforced by a heavy machine gun platoon, attempted to break the Japanese hold on Hill 600-A by a direct attack, but the advance platoon took so much fire that the attack could not move forward. Company K withdrew and artillery support was requested. A 30-minute concentration pounded the forward slopes of the hill with the usual tree-bursts reducing the effectiveness of the fire. Then Company K started forward again. The attack was repulsed. A third attempt, after another mortar and artillery preparation, also failed. Company K then withdrew to the front lines.

The next morning, in preparation for another attack, scouts moved forward toward the enemy position. Inexplicably, after putting up a stiff fight for two days, the enemy had retreated during the night. Only one Japanese body was found in the 25 covered emplacements on the hill. Artillery fire had damaged only a few of the bunkers. The Marines, in attacking for two days, lost four killed and eight wounded.

The next several days were quiet, the Marines resting and preparing for a general

relief along the perimeter by the units of the Army’s Americal Division. There was no further action of any consequence before the Marines departed Bougainville. After the capture of Hill 600-A, the Japanese resistance consisted mostly of periodic shelling of the area around Evansville with 75-mm howitzers and 90-mm mortars. This firing, however, was sporadic and ineffectual. The Japanese quickly retreated past the Torokina River when combat patrols went out to eliminate the enemy fire.

Three final air attacks, two on the 25th and one on the 26th of December, apparently discouraged the Japanese from staging another attack on the perimeter. The object of the attacks was to clear out an area north of Hill 600-A where Japanese activity was reported by patrols. Eighteen torpedo bombers armed with 500-pound and 100-pound bombs blasted the target, and after the attacks patrols found the area abandoned. Trenches and installations indicated that about 800 Japanese had been in the area. A number of patrols across the Torokina River, however, failed to make contact with the enemy.

The relief of the Marine division from Bougainville had been expected since 15 December after the consolidation of the final defense line along Hill 1000 and Hill 600. As additional Army troops continued to arrive at the beachhead, Admiral Halsey directed the Army’s XIV Corps to assume control of the Bougainville operation, and, on 15 December, General Geiger turned over control of the beachhead to the commanding general of the XIV Corps, Major General Oscar W. Griswold. The relief of the 3rd Marine Division by the Americal Division began on the morning of 27 December when all units of the 9th Marines were relieved on frontline positions by the 164th Infantry and moved into bivouac areas in preparation for the return to Guadalcanal. The last units of the 3rd Marines manning perimeter positions were relieved by the 132nd Infantry on the afternoon of the 28th. With two regiments on line, command of the right sector of the beachhead was assumed by Major General John R. Hodge of the Americal Division. The 21st Marines was relieved by the 182nd Infantry on the 1st and 2nd of January 1944. By 16 January, the entire 3rd Marine Division had returned to Guadalcanal.

The raider and parachute regiments remained on Bougainville for two weeks after the 3rd Division departed as part of a composite command led by Lieutenant Colonel Shapley with Lieutenant Colonel Williams as executive officer. The provisional force manned the right flank of the perimeter along the Torokina and spent its time improving defenses and patrolling deep into enemy territory.11 By the end of January, the raiders and parachutists had turned over their positions to the Army and joined the general exodus of IMAC troops from the island. The 3rd Defense Battalion, which stayed on until 21 June, was the sole remnant of the Marine units that had taken part in the initial assault on Bougainville.

The damage to the Japanese forces in the nearly two months of Marine attacks was not overwhelming. The enemy committed his units piecemeal, and, although most of these were completely wiped out, the total loss was not staggering. The Marines estimated that 2,458 enemy soldiers lost their lives in the defense of the Cape Torokina area, the Koromokina counter-landing,

and the counterattacks in the Marine Corps sector. Prisoners numbered 25. Japanese matériel captured was also negligible and consisted of a few field pieces and infantry weapons.

The postwar compilation of Marine Corps casualties in the Bougainville operation totaled 423 killed and 1,418 wounded. The breakdown by major units was: Corps troops—6 killed and 31 wounded; 1st Parachute Regiment (less 2nd Battalion)—45 killed and 121 wounded; 2nd Raider Regiment (provisional)—64 killed and 204 wounded; 3rd Defense Battalion—13 killed and 40 wounded; and 3rd Marine Division—295 killed and 1,022 wounded.12

Completion of the Airfields13

For a period of about 10 days after the landings on Bougainville, the Allies had almost complete air superiority in the Solomons. The Japanese bases in the Bougainville area had been worked over so well and so many times by Allied air strikes and naval bombardments that the enemy experienced extreme difficulty putting them into operation again. As a result, the Japanese were forced to contest the Cape Torokina landings from bases at Rabaul and fields on New Ireland. By the time that the beachhead had expanded to include the Piva fields, the Japanese capability to threaten the beachhead from air bases in the Northern Solomons had been partially restored, and only repeated strikes against the fields at Buka, Kahili, and Ballale kept the Japanese air threat below the dangerous point. On 20 November, ComAirNorSols estimated that at least 15 known enemy airfields within 250 miles of Empress Augusta Bay were either under construction or were repaired and operational once more. Completion of airstrips within the Cape Torokina perimeter was then rushed to meet this growing enemy threat.

During the early stages of the beachhead, the construction of the airfields had been weighed against the immediate need for a road net to insure an adequate system of supply to the front lines. The road net had been given priority, and most of the efforts of the 19th Marines had been directed to this project. After the perimeter road was completed in time to support the fight for the Piva Forks, attention was again turned toward airfield construction. The road network was still far from finished, however. When the various artillery units and support outfits occupying the projected airfield sites were asked to move out of the way of construction work, the answer was usually a succinct, “Over which roads?”14

The Japanese, ironically, gave the construction gangs a big assist. The enemy emplaced several 15-cm howitzers in the high ground east of the Torokina River, and the construction work in the vicinity of the Coconut Grove appealed to his curiosity. As a result, whenever there was no combat air patrol over the beachhead, the Japanese were quite apt to drop shells into the airfield area. The Seabees and the

Piva airfields, the key bomber and fighter strips in the aerial offensive against Rabaul, as they appeared on 15 February 1944. (USN 80-G-250368)

Field artillery missions are fired against Japanese attacking the Torokina perimeter by 155-mm seacoast defense guns of the Marine 3rd Defense Battalion. (SC 190032)

Marine engineers moved to the end of the field which was not being hit and continued to work. The other tenants, though, anxious to avoid repeated artillery shelling, vacated the area.

By the time that Inland Defense Line F had been occupied on 28 November, clearing of the projected bomber and fighter strips was well underway. The work was speeded by the arrival on the 26th of November of the 36th Naval Construction Battalion which brought all its equipment and went to work almost full time on the Piva fields. Meanwhile, the Torokina strip had been unexpectedly put into operation. About noon on the 24th, Seabees and engineers working on the airstrip were amazed to see a Marine scout-bomber preparing to land on the rough runway. Quickly clearing the strip of all heavy engineering equipment, the construction workers stood by while the Marine pilot brought his plane into a bumpy but successful landing. The emergency landing of the plane, damaged in a raid over Buka, initiated operations on the new strip.

Admiral Halsey, whose cheerful messages delighted the South Pacific Forces all through the long climb up the Solomons ladder, provided a fitting note of congratulations on the completion of the fighter strip:

In smashing through swamp, jungle, and Japs to build that air strip, your men have proven there is neither bull nor dozing at Torokina. ... A well done to them all. Halsey.15

The advance naval base and boat pool, which had been underway since the first landings, was also rushed toward completion during the month of November. This gave the III Amphibious Force torpedo boats a wider range, and these ubiquitous craft then prowled along the Bougainville coast as far north as Buka and as far south as the Shortlands in protective patrols.

The Torokina strip was finally declared operational on 10 December, just one month after the initial construction was started. At dawn on the 10th, Marine Fighter Squadron 216, with 17 fighter planes, 6 scout bombers, and 1 cargo plane, landed as the first echelon. The following day, 11 December, three Marine torpedo bombers landed and these were joined six days later by four aircraft from an Army Air Forces squadron. The first direct air support mission was flown on 13 December with Hellzapoppin Ridge as the target, while combat air patrols began flying from the former plantation site on 10 December, the day that the planes arrived. Later in the month, additional flights including night fighter patrols, began operations from the Torokina strip.

After the completion of the first field, work was rushed on the Piva bomber field, and early in December another full-strength naval construction battalion, the 77th, arrived to help with the job. As the network of roads throughout the perimeter was completed, the 71st and 53rd Seabees also went to work on the airfields. The Piva bomber field received its first planes on 19 December, and was completely operational on 30 December. The Piva fighter field, delayed by lack of matting, was operational on 9 January, after the main units of the 3rd Marine Division were withdrawn from the island.

With the opening of three Allied airfields on Bougainville, the Japanese capability to threaten the Allied position on

Cape Torokina from the air was virtually eliminated. The tactical importance of these airstrips was demonstrated in the quick support given the ground troops in the attack on Hellzapoppin Ridge, but the advantage was strategic as well as tactical. The Torokina airfields brought Allied air power to within 220 miles of Rabaul and allowed fighter aircraft to escort bombers on air strikes against Japanese bases on New Britain and New Ireland. The completion of the three fields on Bougainville, and a fourth field at Stirling Island in the Treasurys, marked the successful achievement of the primary aim of the Bougainville operation.

The constant pressure which the expanding air strength of the Allies exerted upon the Japanese installations was reflected in the attempts which the enemy made to delay the Torokina airstrips. During the first 26 days of operation at Torokina, the beachhead had 90 enemy alerts. The vigilance of the ComAirNorSols fighter cover and the accuracy of the Marine 3rd Defense Battalion’s antiaircraft fire was indicated by the fact that bombs were dropped during only 22 of these alerts. Casualties from enemy air action up to 26 November were 24 killed and 96 wounded. Damage was restricted mainly to the boat pool and supply stocks on Puruata Island.

During the time that the 3rd Marine Division remained on the island, the Japanese managed to bomb the perimeter only five more times, and the interval between alerts grew increasingly lengthy. For the entire period 1 November to 28 December, there were 136 enemy air alerts with bombs dropped during only 27 of these alerts. The total casualties in enemy air raids were 28 killed, 136 wounded, and 10 missing.

Japanese Counterattacks, March 194416

Several weeks after the 3rd Marine Division departed Bougainville, the XIV Corps became aware of gradually increasing enemy activity around the area of the Torokina River and the right sector of the beachhead now being held by the Americal Division. Immediate offensive efforts were directed toward the Torokina sector, and aggressive patrols by the Americal Division erased the threat to the perimeter by driving the Japanese out of prepared positions along the coast near the Torokina River. The bunkers and pillboxes encountered were destroyed. The perimeter, however, was not extended to cover this area.

The following month, Japanese patrol action was more aggressive, and throughout February the entire perimeter was subjected to a number of sharp probing attacks by small groups of enemy soldiers. The two frontline divisions, keenly aware that the perimeter might soon be tested by another determined Japanese attack, prepared extensive defenses to meet it. Fortifications in depth were constructed, and the entire front was mined and wired where possible.

The Japanese, after being forced to withdraw from the heights around the Torokina River late in December, began planning the counterstroke about the middle of January. Determined to end the Allied possession of the Cape Torokina area, the enemy readied the entire 6th Division, plus a number of special battalions from the Seventeenth Army. This force began training for the operation while support troops started building roads toward the Cape Torokina area from Mawareka. This offensive was to be a joint Army-Navy effort, but when Truk Island in the Central Pacific was hit by a large Allied carrier force on 16 February 1944, the remainder of the naval air strength at Rabaul was dispatched to Truk. The Seventeenth Army then carried on the operation alone.

As expected by Allied intelligence officers, the trail net from Mosigetta–Mawareka was the main route of travel, and a rough road was completed during the early part of the year. This route had its share of troubles, though. Sections of the road were washed out by rains, and swollen rivers carried away the hasty bridges thrown across them by the Japanese engineers. Additionally, the Japanese activity along this road was a prime target for repeated aerial attacks from patrolling Allied planes. Japanese barge movements along the coast were so harassed by Allied torpedo boats, LCI gunboats, and patrol planes that only a few of the barges remained afloat by March. In the end, the enemy force was required to move overland through the jungle, tugging and pulling artillery and supplies behind.

The Japanese offensive, known as the Ta operation, included elements from five infantry regiments—the 13th, 23rd, 45th, 53rd, and the 81st—and two artillery regiments. The attack force numbered about 11,700 troops out of a total force of some 15,400. The general plan of the Ta operation was a simultaneous attack on the Allied perimeter from the northwest, north, and east, while the artillery units pounded the objective from positions east of the Torokina River. The attack opened on 8 March with a simultaneous shelling of the Torokina and Piva airstrips and a sudden thrust at the 37th Division lines near Lake Kathleen in the center of the perimeter.

The Army division held its positions against light probing attacks and waited for the all-out assault. The following day three battalions from the 13th and 23rd Infantry slashed at 37th Division positions in an effort to penetrate the Army lines and obtain high ground where they could emplace artillery weapons to threaten the airfields. The 145th Infantry bore the brunt of these attacks, and by the 12th of March had made three counterattacks to dislodge the enemy forces and restore the lines. During these bitter struggles, the entire enemy force was virtually annihilated; 37th Infantry Division troops counted 1,173 dead Japanese in the area after the attacks.

While this fight raged, another strong Japanese force suddenly assaulted the Americal Division in the area of the upper Torokina River. The action here was considerably less violent but more protracted than in the 37th Division area, and the Japanese forces were not driven back until the 29th of March. The enemy in this area suffered 541 casualties.

In sharp contrast to the weeks of November and December, the main enemy

thrusts during the March counterattack continued in the perimeter sector held by the 37th Division. After the staggering repulse near the center of the perimeter, the Japanese forces moved toward the Laruma area, where four more determined attacks were launched against the Army positions. A coordinated attack in two places on the northwest side of the perimeter on the 13th and 14th was repulsed by the 129th Infantry, and more than 300 Japanese were killed. On the 17th of March, the Japanese struck another blow at the 37th Division positions and were met by a tank-infantry counterattack that killed another 195 enemy.

The sixth and final attack against the XIV Corps perimeter was launched on the 24th of March. Japanese fanaticism carried the attack as far as one of the battalion command posts of the 129th Infantry before the penetration was sealed off. Another 200 Japanese perished in this last attack. The following day, XIV Corps artillery shelled the retreating Japanese, and the last bid by the enemy to retake the Cape Torokina area was over. Admiral Halsey, describing the “Ta” operation later, reported:–

The attack came against positions that had been carefully prepared in depth, with well-prepared fields of fire and manned by well-disciplined, healthy, and ready-to-go troops of the 37th and Americal Division. Some damage was done by enemy artillery but the damage did not prevent aerial operations. The Japanese infantry attacks were savage, suicidal, and somewhat stupid. They were mowed down without mercy and the attack was actually broken up by the killing of a sufficient number of Japanese to render them ineffective. At this writing, over 10,000 Japanese have been buried by our forces on Bougainville. The remainder can probably manage to keep alive but their potential effectiveness and heavy weapons have been destroyed.17

The XIV Corps estimated that more than 6,843 Japanese had died in the futile charges against the strong Allied positions from 8 to 25 March. These casualty figures compare favorably with Japanese records which indicate that the Ta attack force lost 2,389 killed and 3,060 wounded. In addition, various supporting units under direct control of the Seventeenth Army suffered casualties of about 3,000 killed and 4,000 wounded.18

At the time of the attack against the XIV Corps perimeter, the Antiaircraft and Special Weapons Groups of the Marine 3rd Defense Battalion were operating under the tactical control of Antiaircraft Command, Torokina, an XIV Corps grouping of all air defense weapons. For some time, enemy activity over the beachhead had been restricted because of the almost complete dominance of Allied aircraft. As a result, the Marine weapons were seldom fired. When the Japanese attack was launched, the 90-mm batteries were employed as field artillery.

The Marine batteries were usually registered by an Army fire direction center on various targets beyond the range of light artillery units and adjusted by aerial observers. Most of the firing missions were targets of opportunity and night harassing registrations on enemy bivouac and supply areas. The Marine weapons fired a total of 4,951 rounds of ammunition in 61 artillery missions.19

On the 13th of March, two 90-mm guns from the Marine unit were moved toward the northwest side of the perimeter with the mission of direct fire on a number of enemy field pieces and other installations located on a ridge of hills extending in front of the 129th Infantry. Emplacement of the guns in suitable positions for such restricted fire was difficult, but both guns were eventually employed against limited targets of opportunity. The guns were later used to greater advantage to support the soldiers in local counterattacks against the Japanese forces.

The 155-mm seacoast defense guns of the Marine battalion were also used as field artillery in defense of the perimeter. The Marine battery was called upon for 129 firing missions in general support of the Army defenses and was usually employed against long-range area targets. The big guns fired 6,860 rounds, or 515 tons of explosives, against enemy positions.

In addition, two of the 40-mm guns from the Special Weapons Group were moved into the front lines in the Americal Division sector for close support. There were few suitable targets for the guns in the slow action in this area, and only two or three bunkers were hit by direct fire. One weapon, however, fired over 1,000 rounds in countermortar fire and to strip obstructing foliage from enemy positions. Targets being scarce, the guns were sometimes used as sniping weapons against individual Japanese.20

The defense battalion was the last Marine Corps ground unit withdrawn from Bougainville. It departed Cape Torokina on 21 June, nearly eight months after the initial landings of the battalion on 1 November with the assault waves. The withdrawal came one week after Admiral Halsey’s South Pacific Command was turned over to Vice Admiral John H. Newton and all the Solomon Islands were annexed as part of General MacArthur’s Southwest Pacific Command. The South Pacific campaign against the Japanese was virtually ended. Ultimately, the Cape Torokina area was occupied by Australian forces which, by the end of the war, were closing slowly on Numa Numa and the last remnants of the Bougainville defenders.

Conclusions

In an analysis of the operations against the Japanese in the Northern Solomons, three points of strategic importance are apparent. The first of these is that despite the risk inherent in attacking deep into enemy-held territory, the Allied forces successfully executed such a venture. Diversionary and subsidiary actions were so timed and executed that the Japanese were deceived as to the intentions and objective of the final attack. The South Pacific forces also gambled and won on the premise that the ever-increasing superiority of Allied air and sea power would counterbalance the vulnerability of extended supply lines attendant upon an operation so close to Rabaul.

Another point is that, although the operations in Bougainville and the Treasurys were planned, directed, and executed by South Pacific Forces, the campaign was partially a maneuver to provide flank security for the advance of the Southwest Pacific Forces along the northern coast of New Guinea. The need to strike at a point which would insure this flank security was the factor which resulted in the selection

of Cape Torokina as the I Marine Amphibious Corps objective.

The third point is that the Bougainville campaign was wholly successful, with a minimum of lives lost and matériel expended. Seizure of a shallow but broad beachhead by Marine units and the expansion of this perimeter with the subsequent and continued arrival of Army reinforcements was an economical employment of both amphibious troops and infantry.

The operations in the Northern Solomons knocked the Japanese off-balance. The only enemy activity was a day-to-day reaction to Allied moves. After 15 December, Allied air superiority south of Rabaul was unchallenged, and the Japanese cancelled further naval operations in the latitude of the Bougainville operation. There were other considerations, however. The enemy was pressed by additional Allied moves in the Central Pacific, the loss of the Gilbert Islands, and the continued advance of General MacArthur’s forces in the Southwest Pacific. The success at Bougainville, however, led to the eventual collapse of the enemy’s defensive positions in the Bismarcks.

The Bougainville campaign was intended to accomplish the destruction of enemy air strength in the Bismarcks; not only was this accomplished but the by-products of the campaign were so extensive that the subsequent operations at Green Island and Emirau were accomplished virtually without enemy opposition, and the entire enemy offensive potential in the Bismarcks area was destroyed. In the matter of ultimate achievement and importance in the Pacific War, the Bougainville operation was successful beyond our greatest hopes.21

By tactical considerations, the planning of the Northern Solomons campaign was daring, yet sound. The diversionary landing on Choiseul and the operations in the Treasurys were conceived to mislead the Japanese, and these maneuvers served as the screen behind which the I Marine Amphibious Corps moved toward the actual point of attack. The surprise achieved by the landings at Empress Augusta Bay is evidence of astute, farsighted thinking behind these operations.

The tactical stroke which decided the success of the Bougainville operation was the selection of the Cape Torokina beaches as the landing site. To pick a landing area lashed by turbulent surf, with tangled jungle and dismal swamps immediately inland, was a tactical decision which the Japanese did not believe the Allied forces would make. Amphibious patrols had failed to scout the exact beaches chosen and general knowledge of the area was unfavorable. Despite these disadvantages, the shoreline at Cape Torokina was picked because the Japanese had decided not to defend such an unlikely area in strength.

When the I Marine Amphibious Corps was relieved by XIV Corps on 15 December, General Geiger’s Marine forces could leave the island confident that the beachhead was firmly anchored along the prescribed lines and that the mission was complete. Advance naval base facilities were installed and functioning; one fighter strip was in operation and another underway, and a bomber field was nearly complete. Equally as important, a road net capable of carrying all anticipated traffic was constructed or nearly finished throughout the beachhead. This last achievement, as much as the rapid completion of airfields, insured the continued existence of the Cape Torokina perimeter against Japanese attacks.

That the operations ashore were successful though faced by three formidable obstacles—Japanese forces, deep swamps, and dense jungle—is a tribute to the cooperation of the Marine Corps, Army, and Navy units assigned to the I Marine Amphibious Corps.

For the 3rd Marine Division, which formed the bulk of the IMAC forces initially, the months of hard fighting established skills and practices which lasted throughout the Pacific campaign. The Marines of General Turnage’s division first experienced the difficulties of maintaining supply and evacuation while under enemy fire at Cape Torokina. If there had been any misgivings about committing an untested division to such a task, these were dispelled by the manner in which the Marines conducted the operation. After the campaign, General Turnage wrote: “From its very inception it was a bold and hazardous operation. Its success was due to the planning of all echelons and the indomitable will, courage, and devotion to duty of all members of all organizations participating.”22

By the time of the Piva Forks battle, the 3rd Division Marine was a combat-wise and skilled jungle fighter capable of swift movement through swamps and effective employment of his weapons. By the end of the campaign, the Marine was a veteran soldier, capable of offering a critical appraisal of his own weapons and tactics as well as those of his opponent.

This increased fighting skill was reflected by mounting coordination between all combat units, with lessening casualties. In this respect, the 3rd Medical Battalion achieved a remarkable record of rescue operations which, despite the complexities of evacuation, resulted in less than one percent of the battle casualties dying of wounds. Aid stations were located as close to the front lines as possible. Wounded Marines were given emergency treatment minutes after being hit. The casualties were removed by amtracs to hospitals in the rear, or, in the case of seriously wounded Marines, to more extensive facilities at Vella Lavella. The hospitals on the beach were subjected to air raids and shelling, but the treatment of wounded continued despite these handicaps.

Disease incidence was low, except for malaria which had already been contracted elsewhere. The construction work on the airfields and roads resulted in the draining of many adjacent swamps which aided the malaria control. There were no cases of malaria which could be traced to local infection, and dysentery and diarrhea were practically nonexistent—a rare testimonial to the sanitary regulations observed from the start of the operation. Before the campaign, many preventive measures were taken. Lectures and demonstrations which stressed the value of clothing, repellents, bug spray, and head and mosquito nets were part of the preoperation training. Their effect and the discipline of the Marines is reflected in the fact that few men were evacuated because of illness.

The Marines learned that, with few exceptions, jungle tactics were a common sense application of standard tactical principles and methods to this type of terrain. Control of troops was difficult but could be accomplished by the “contact imminent” formation described earlier. During most of the fighting, command posts were situated as close to the front lines as

possible—sometimes as near as 75 yards. Although this close proximity sometimes forced the command post to defend itself against enemy attacks, Marine officers felt that such a location provided more security. Additionally, this close contact allowed rapid relay of information with resultant quick action. The command post was usually in two echelons—the battle or forward CP with the commanding officer and the operations and intelligence officers, and the rear command post manned by the executive officer and the supply and communications officers.

Defense in the jungle usually took the form of a thinly-stretched perimeter with a reserve in the center. Organization of the positions was seldom complete. Sometimes a double-apron fence of barbed wire blocked some avenue of approach, but usually a few strands of booby-trapped wire sufficed. The Marines took a lesson from the Japanese and cleared fields of fire by removing only a few obstructing branches from trees and underbrush.

As the fighting moved through the jungles, the Marines found that the automatic rifle (BAR) was the most effective weapon for close combat. Light and capable of being fired instantly, the BAR was considered superior to the light machine gun for most occasions. The machine gun, however, had its adherents because of its mobility and low silhouette. These rapid-fire weapons and the highly regarded M-1 rifle were used most of the time in jungle attacks. The .30 caliber carbine most Marines dismissed as too light in hitting power, too rust-prone, and too similar in sound to a Japanese weapon. The heavy machine gun was too heavy and too high for jungle work except for sustained firing in a defensive position.

Supporting weapons such as the 37-mm antitank gun and the 75-mm pack howitzer were effective in the dense foliage, but these guns were difficult to manhandle into position and could not keep up with the advance in a rapidly changing tactical situation. The 81-mm mortars, augmented by the lighter 60-mm tubes, provided most of the close support fires. These weapons achieved good results on troops in the open, but were too light for emplaced bunkers. The Marines were supported on two occasions by an Army unit with chemical mortars (4.2 inch), and these were found to be extremely effective against pillboxes and covered positions.

Several attempts were made to use flame throwers in stubborn areas, and these weapons had a demoralizing effect on the Japanese. Many bunkers were evacuated by the enemy before the weapons could be fired against the position. The flame throwers quickly snuffed out the lives of the Japanese remaining in their emplacements. Ignition of the fuel was difficult in the jungle, but Marines solved this by tossing incendiary grenades against a bunker and then spraying the position with fuel. The 2.36-inch antitank bazooka was used on enemy emplacements on Hellzapoppin Ridge, but the crews were unable to get close enough for effective work. The experimental rockets, which were used in the latter stages of the campaign, were highly inaccurate against small area targets and revealed the positions of the Marines.

The Japanese proved to be as formidable an enemy as the Marines expected. The Japanese defenses were well-placed and skillfully concealed and camouflaged. Expenditure of ammunition was small and fire from the bunkers was deadly. Foxholes were cleverly camouflaged and only

narrow, inconspicuous lanes of fire were cleared. Fire was limited to short range. Most Marines were killed within 10 yards of enemy positions. In such actions, the rate of the wounded to the dead was high, and the majority of bullet wounds were in the lower extremities. This reflected the Japanese tendency to keep firing lanes low to the ground.

Grenades were used extensively, both by hand and from launchers. The concussion of these enemy grenades was great but fragmentation was poor. The Japanese weapon most feared by the Marines was the 90-mm mortar which the enemy employed with great skill. The enemy shell contained an explosive with a high velocity of reaction which resulted in a concussion of tremendous force. The sound of this blast was almost as terrifying as the actual burst. One Marine regiment, assessing the effect of this weapon against the Marines, estimated that at least one-fifth of all battle casualties were inflicted either by the blast concussion or fragments from this enemy shell.

The Japanese, however, displayed what the Marines believed was amazing ineptness in the tactical use of artillery. The gunnery was excellent, and fire from the light and heavy artillery pieces was accurately placed on road junctions, observations points, front lines, and supply dumps. But the placement of firing batteries was so poor that, almost without exception, the Japanese positions were detected and destroyed within hours after firing was started. The enemy fired concentrations of short duration, but, despite this, the muzzle blasts of the weapons were detected and the positions shelled by counterbattery fire.

The enemy may have lacked shells because of the difficulty of supply through the jungle, but “there is no reasonable explanation for the Japanese repeatedly placing their guns on the forward slopes of hills under our observation and then firing them even at twilight or night when the muzzle flashes of the guns fixed their positions as surely as if they had turned a spotlight on them.”23

As for the artillery support offered by the 12th Marines (and later the 37th Division units), the 3rd Marine Division stinted no praise in reporting that the accurate artillery fire was the dominant factor in driving the Japanese forces out of the Torokina area. At least half of the enemy casualties were the direct result of artillery shelling. The preattack bombardment fired before the Battle of Piva Forks was devastating evidence of the force of sustained shelling. The Marines, aware that the all-around defensive system of the Japanese discouraged flank attacks, depended upon the fires of the supporting artillery to pave the way for the infantry to close with the enemy. This infantry-artillery cooperation was one of the highlights of the Bougainville campaign. A total of 72,643 rounds were fired by Marine artillery units in support of the attacks by the IMAC forces.

The greatest advance in supporting arms techniques was in aviation. Prior to the operation, the Marines had a tendency to regard close air support as a risk. The infantrymen wanted and needed direct support from the air, but their faith as well as their persons had been shaken on occasion by air support being too close. Ground troops felt insecure with only smoke to mark their front lines and targets, and airmen were hesitant to bomb after it became known that the Japanese

shot white smoke into the Marine lines to deceive the airmen into bombing their own people. Since it was known from the New Georgia campaign that the enemy troops tended to close in against the front lines to wait out a bombing attack, preparations for close air support at Bougainville started with the idea of developing techniques which would result in maximum accuracy at minimum distance from Marine lines.

Prior to the operation, three air liaison parties were organized and trained. In addition, each battalion and regiment sent a representative to the training school so that each infantry command post would have a man available to direct the close support missions. The prestrike briefings by both the strike operations officer and a ground officer familiar with the terrain was another innovation. How well this system succeeded is demonstrated by the fact that in 10 missions requested by forces on Bougainville, the only casualties to ground troops were from bombs inexplicably dropped 600 yards from a well-marked target. The other nine strikes were highly successful and in two instances were made within 75 yards of the front lines without harm to the infantry.

Before the Cape Torokina operation, air support was employed mostly against targets beyond the reach of artillery. The Bougainville fighting showed that air could be employed as close to friendly troops and as accurately as artillery, and that it was an additional weapon which could be used to surprise and overwhelm the enemy. Much credit for developing this technique should go to Lieutenant Colonel John T. L. D. Gabbert, the 3rd Division Air Officer, and the ground and flying officers who worked with him.

The work of the amphibian tractor companies is another highlight of the operation. Throughout the campaign, these machines proved invaluable. Had it not been for the amtracs, the supply problem would have been insurmountable. The 3rd Amphibian Tractor Battalion transported an estimated 22,992 tons of rations, ammunition, weapons, organizational gear, medical supplies, packs, gasoline, and vehicles, as well as reinforcements and casualties. A total of 124 amtracs were landed, but the demand was so great and jungle treks so difficult that only a few were in operating order at any one time. These, however, did yeoman work, and the list of the duties and jobs performed by these versatile machines varied from rescuing downed aviators from the sea to conducting scouting trips along the front lines. The appreciation and affection felt by the Marines for these lumbering lifesavers is best expressed by this comment:–

Not once but all through the campaign the amphibian tractor bridged the vital gap between life and death, available rations and gnawing hunger, victory and defeat. They roamed their triumphant way over the beachhead. They ruined roads, tore down communication lines, revealed our combat positions to the enemy—but everywhere they were welcome.24

Not to be overlooked in an analysis of the campaign is the contribution to the success of the Cape Torokina operation by the 19th Marines. The Marine pioneers and engineers, with a Seabee unit attached, landed with the assault waves on D-Day and for some time functioned as shore party personnel before being released to

perform the construction missions assigned. Only one trail to the interior existed at the time of landing; in slightly more than two weeks a rough but passable road connected all units along the perimeter. This provided a vitally necessary supply and reinforcement route for further advances.

One of the reasons the Marines gained and held the perimeter was this ability to construct quickly the necessary roads, airfields, and supply facilities. Engineering units and Seabees of the I Marine Amphibious Corps built and maintained 25 miles of high-speed roads as well as a network of lesser roads within the space of two months. This work was in addition to that on two fighter strips and a bomber field. The Japanese had not developed the Cape Torokina area and therefore could not defend it when the Marines landed. After the IMAC beachhead was established, the Japanese employed a few crude pieces of engineering equipment in an attempt to construct roads from the Buin area toward Empress Augusta Bay. The project was larger than the equipment available. The attacking force for the Ta operation had to struggle more than 50 miles through jungle, swamps, and rivers tugging artillery, ammunition, and rations over rough jungle trails. XIV Corps was able to meet this threat over IMAC-constructed roads, which permitted reinforcements to rush to the perimeter at high speed.25

The solution of the logistics muddle, which started on D-Day and continued for several weeks, was another accomplishment which marked the Bougainville campaign. With the exception of the unexpected accumulation of supplies and equipment which nearly smothered the beaches early in the operation, logistical planning proved to be as sound as conditions permitted. An advance base at Vella Lavella for a source of quick supply to augment the short loads carried ashore on D-Day proved to be unnecessary in the light of later events. The III Amphibious Force lost a minimum of ships during the Bougainville operation, a stroke of good fortune that accrued as a result of air domination by the Allies. This permitted direct and continued supply from Guadalcanal. More than 45,000 troops and 60,000 tons of cargo were unloaded in the period 1 November-15 December, with no operational losses. With the exception of the first two echelons, all supplies were unloaded and the ships had departed before nightfall.

The lack of an organized shore party for the sole purpose of directing and controlling the flow of supplies over the beachhead was partially solved by the assignment of combat troops for this duty. Luckily, the enemy situation during the early stages at Cape Torokina was such that nearly 40 percent of the landing force could be diverted to solving the problem of beach logistics. This led to many complaints by assault units, which—despite only nominal opposition by the Japanese during the landing stages—protested the loss of combat strength at such a time.

It is to General Vandegrift’s credit that quick unloading was assured by the assignment of infantrymen to the task of cargo handling. This, however, was a temporary measure to meet an existing problem and would have been unfeasible in future operations where opposition was more determined. His action, though, was an indication of the growing awareness that

beach logistics was a vital command responsibility. It is interesting to note that after the Bougainville operation a number of units recommended that the shore party be augmented by additional troops or personnel not essential to operations elsewhere. Later in the war, combat leaders realized that nothing was more essential than an uninterrupted flow of supplies to the assault units, and that the complicated task of beach logistics must be handled by a trained shore party organization and not an assigned labor force of inexperienced personnel.

The Bougainville operation was no strategic campaign in the sense of the employment of thousands of men and a myriad of equipment requiring months of tactical and logistical maneuver. As compared with the huge forces employed in later operations, it was a series of skirmishes between forces rarely larger than a battalion. Yet, with all due sense of proportion, the principal engagements have the right to be called battles, from the fierceness and bravery with which they were contested and the important benefits resulting from their favorable outcome.26

The campaign for the Northern Solomons ended as the Bougainville operation drew to a close. The end of the Solomons chain had been reached, and new operations were already being planned for the combined forces of the Southwest and South Pacific commands. The general missions of the campaign had been accomplished. Rabaul was neutralized from airfields on Bougainville, and the victory won by Marines and soldiers at Cape Torokina allowed other Allied forces to continue the attack against the Japanese at other points.

The final accolade to the Bougainville forces is contained in the message General Vandegrift sent his successor, General Geiger, when the Marine forces returned to Guadalcanal:–

I want to congratulate you on the splendid work that you and your staff and the Corps did on Bougainville. The spectacular attack on Tarawa has kind of put Bougainville off the front page; but those of us who know the constant strain, danger, and hardship of continuous jungle warfare realize what was accomplished by your outfit during the two months you were there.27