Part IV: The New Britain Campaign

Blank page

Chapter 1: New Britain Prelude

GHQ and ALAMO Plans1

By late November, the parallel drives of South and Southwest Pacific forces envisaged in ELKTON plans had reached the stage where General MacArthur was ready to move into New Britain, with the main target the enemy airfields at Cape Gloucester on the island’s western tip. The timing of the attack depended largely upon the availability of assault and resupply shipping, and the completion of Allied airfields on Bougainville and in the Markham-Ramu River valley at the foot of the Huon Peninsula. Complete control of the Vitiaz Strait, the prize sought in the pending operation, would give the Allies a clear shot at the Japanese bases on the New Guinea coast and a secure approach route to the Philippines.

The airstrips building within the IMAC perimeter on Bougainville provided the means for a heightened bomber offensive against Rabaul—raids which could count on strong fighter protection. With the completion of Torokina Field expected in early December, and the first of the Piva Field bomber runways ready by the month’s end, SoPac planes could throw up an air barrier against enemy counterattacks on landings on western New Britain. In like manner, the new Markham-Ramu valley fields increased the potential of American and Australian air to choke off raids by the Japanese Fourth Air Army based at Madang and Wewak and points west on the New Guinea coast.

While men of the Australian 9th Division drove the Japanese garrison of Finschhafen back along the shore of the Huon Peninsula toward Sio, other Australians of the 7th Division fought north through the Markham-Ramu uplands, keeping the pressure on the retreating enemy defenders. Behind the assault troops, engineers worked feverishly to complete airfields at Lae and Finschhafen, and at Nadzab and Gusap in the valley. Completion schedules were slowed by the seemingly endless rain of the New Guinea region, and the most forward strip, that at Finschhafen, could not be readied for its complement of fighters before 17 December. An all-weather road building from Lae to Nadzab, key to the heavy duty supply of the valley air bases, was not slated to be fully

operational until the 15th. Prior to that date, all troops and equipment were airlifted into the valley by transports of the Allied Air Forces.

Until the new forward bases were ready to support attacks on the next SWPA objectives, all the shipping available to Admiral Barbey’s VII Amphibious Force was tied up moving troops and supplies forward from depots at Townsville, Port Moresby, and Milne Bay. The landing craft and ships essential to a move across Vitiaz Strait against Cape Gloucester could not be released for rehearsal and loading until 21 November at the earliest.

These factors, coupled with the desire of planners to execute the movement to the target during the dark of the moon, combined to set D-Day back several times. The target date first projected for Cape Gloucester was 15 November; the date finally agreed upon was 26 December. In both cases, provision for a preliminary landing on the south coast of New Britain was also made, the advance in scheduling here being made from 9 November to 15 December. Altogether, the planning for the operation was characterized by change, not only in landing dates, but also in the targets selected and the forces involved.

General MacArthur chose to organize his troops for the operations on New Guinea and against Rabaul into two task forces. The headquarters of one, New Guinea Force, under Australian General Sir Thomas A. Blamey, conducted the Papuan campaign and directed the offensive operations on the Huon Peninsula. The first operation of the other, New Britain Force, led by Lieutenant General Walter Krueger, USA, was the seizure of Woodlark and Kiriwina. Krueger’s command, known as ALAMO Force after July, was next charged with the execution of DEXTERITY (the seizure of Western New Britain).

Technically, Blamey, serving as Commander, Allied Land Forces, had operational control of the national contingents assigned to his command. This assignment included the U.S. Sixth Army, led by Krueger, the Australian Military Forces, also led by Blamey, and the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army. Actually, most of the troops in Sixth Army were assigned to ALAMO Force, which MacArthur kept directly under his General Headquarters (GHQ). The effect of this organizational setup was to make New Guinea Force an Australian command to which American troops were infrequently assigned and to fix ALAMO Force as an American command with very few Australian units.

In contrast to the situation on land, no separate national task forces were created at sea or in the air. At a comparable level with Blamey, directly under MacArthur were two American officers, Vice Admiral Arthur S. Carpender, who led Allied Naval Forces, and Lieutenant General George C. Kenney, who headed Allied Air Forces. Each man was also a national contingent commander in his own force; Carpender had the Seventh Fleet and Kenney the Fifth Air Force. The Dutch and Australian air and naval forces reported to the Allied commanders for orders.

At this time, amphibious operations in the Southwest Pacific, unlike those in Halsey’s area where naval command doctrine prevailed, were not conducted under unified command lower than the GHQ level. Control was effected by cooperation and coordination of landing and support

forces. Neither amphibious force nor landing force commander had sole charge during the crucial period of the landing itself; the one had responsibility for movement to the target, the other for operations ashore. This deficiency in the control pattern, which was recognized as a critical “weakness” by MacArthur’s G-3, Major General Stephen J. Chamberlin, was not remedied until after DEXTERITY was officially declared successful and secured.2

Despite its complexity, the command setup in the Southwest Pacific had one indisputable virtue—it worked. And it worked with a dispatch that matched the efforts of Halsey’s South Pacific headquarters. Both GHQ and ALAMO Force displayed a tendency to spell out tactical schemes to operating forces, but this was a practice more annoying to the commanders concerned than harmful. Since frequent staff conferences between cooperating forces and the several echelons of command was the rule in planning phases, the scheme of maneuver ordered was inevitably one acceptable to the men who had to make it work. In like manner, differences regarding the strength of assault and support forces were resolved before operations began. When, at various points in the evolution of DEXTERITY plans, the differences of opinion were strong, the resolution was predominantly in favor of the assault forces.3

The GHQ procedure in planning an operation was to sketch an outline plan, including forces required and objectives, and then to circulate it to the Allied commands concerned for study, comment, and correction. In the case of DEXTERITY, the principal work on this first plan was done by Lieutenant Colonel Donald W. Fuller, one of the three Marines who were assigned to MacArthur’s headquarters as liaison officers shortly after the 1st Division left Guadalcanal. With the others, Lieutenant Colonels Robert O. Bowen and Frederick L, Wieseman, Fuller soon became a working member of the GHQ staff. He summarized the planning sequence at this stage by recalling:–

The routine was then to let all services study the outline plan for a prescribed period and then hold a conference in GHQ. The commanders concerned [including General MacArthur], the General Staff, and Technical Services GHQ then discussed the plan and, if any objections were made, they were resolved at that time. After everyone appeared happy, the plan was filed. It was never issued formally but merely handed out for comment. The next step was the issuance of orders which were called “operations instructions.” This was actually the only directive issued to conduct an operation ... never while I was there was any command ever directed to conduct an operation in accordance with General MacArthur’s outline plan.4

On 6 May, ALAMO Force had received a warning order from GHQ which set a future task for it of occupying western New Britain by combined airborne and amphibious operations. Engrossed as it then was in preparations for the Woodlark-Kiriwina landings, General Krueger’s headquarters had little time for

advance planning, but, as the weeks wore on toward summer, attention focused on the target date in November. Although the assault troops were not yet formally named, there was no doubt that they would be drawn from the 1st Marine Division, and the division sent some of its staff officers to Brisbane in June to help formulate the original plans. These Marines served with Sixth Army’s staff in the Australian city, the location of MacArthur’s headquarters as well as those of the principal Allied commands. In the forward area, at Port Moresby in the case of GHQ, and Milne Bay for Krueger’s task force, were advance headquarters closer to the scene of combat. Members of the Sixth Army staff were detailed to additional duty as the ALAMO Force staff, and the traffic between Brisbane and New Guinea was heavy. After the initial GHQ outline plan was circulated on 19 July, ALAMO planners were not long in coming up with an alternate scheme of their own.

Conference discussions tended to veer toward the ALAMO proposals which differed mainly in urging that more forward staging areas be used that would place troops nearer the targets selected and thus conserve shipping. A second outline plan circulated on 21 August was closer to the ALAMO concept and named the units which would furnish the assault elements: 1st Marine Division; 32nd Infantry Division; 503rd Parachute Infantry Regiment. By mid-September, preparations for the operation were far enough along so that detailed planning could be undertaken. MacArthur’s operations instructions to cover DEXTERITY were published on the 22nd; six days later, an ALAMO Force draft plan was sent to GHQ for approval.

After a summer of discussion, refinement, and change, General Krueger’s plan called for seizure of a foothold on New Britain’s south shore at Lindenhafen Plantation on 14 November and subsequent operations to neutralize the nearby Japanese base at Gasmata. Once the Gasmata effort was well underway, the main DEXTERITY landings would take place at Cape Gloucester with the immediate objective the enemy airfields there. The eventual goal of the operation was the seizure of control of Western New Britain to a general line including Talasea on the north coast’s Willaumez Peninsula and Gasmata in the south.

The assault force chosen for the Gasmata operation (LAZARETTO) was the 126th Infantry,5 reinforced as an RCT with other 32nd Division units and Sixth Army troops. To carry out operations against Cape Gloucester (BACKHANDER), General Krueger designated the 1st Marine Division, reinforced by the 503rd Parachute Infantry. In ALAMO Force reserve for all DEXTERITY operations was the remainder of the 32nd Division. While the 32nd was a unit of the Sixth Army assigned to ALAMO, both the Marine and parachute units were assigned from GHQ Reserve, which came immediately under MacArthur’s control.

The basic scheme of maneuver proposed for BACKHANDER called for a landing by the 7th Marines (less one of its battalions),

organized as Combat Team C, on north shore beaches between the cape and Borgen Bay. Simultaneously, the remaining battalion of the 7th, suitably reinforced, would land near Tauali just south of the cape to block the trail leading to the airfields. Shortly after the Marines landed, the 503rd was to jump into a drop zone near the airfields and join the assault on enemy defenses. The 1st Marines, organized as Combat Team B, would be in immediate reserve for the operation with Combat Team A (the 5th Marines) on call subject to ALAMO Force approval. The intent of the operation plan was to use as few combat troops as possible and still accomplish handily the mission assigned.

On 14 October, GHQ, returned the ALAMO plan approved and directed that Combat Team B be staged well forward along the New Guinea coast, at Oro Bay or Finschhafen rather than Milne Bay, if it developed that Allied Air Forces could provide adequate daylight cover over loading operations. Similarly, authorization was given to increase the strength of the assault forces if late intelligence of the enemy garrison developed the need. In order to conserve operating time and get more value out of the shipping available, maximum use was ordered made of Oro Bay as a supply point for BACKHANDER.

After considering the ALAMO Force plan, Admiral Carpender agreed to use two of his overworked transports together with all the LSTs, LCIs, and smaller amphibious craft available to Seventh Fleet to support the operation. Close on the heels of this commitment, Admiral Barbey protested the exposure of his priceless transports to enemy attack and proposed instead “to restrict the assault ships to those which could discharge their troops directly to the beaches,” in order “to reduce the turn-around time and thereby reduce the hazards from air attack.”6 The matter was brought to MacArthur’s attention, but he refused to specify the equipment to be used; however, he did relay to General Krueger his intention that all “troops and supplies that you wished landed must be landed and in such order as you consider necessary.”7 The Seventh Fleet commander then made arrangements to borrow six APDs from Third Fleet in return for extending the loan period of four APDs then being used by Halsey in South Pacific operations. Once replacement ships were obtained, the attack transports were scratched from the task organization of assault shipping.

When the first ALAMO plan for DEXTERITY was being prepared, the probable enemy garrison in the target area was estimated at being between 3,000 and 4,000 men. Toward the end of October, the evidence assembled by coastwatchers, scouts, and other intelligence agencies pointed strongly to a sharp increase in the number of defenders, particularly in the Cape Gloucester vicinity. Krueger’s order of battle officers now considered that there were as many as 6,300 troops to oppose the landings and probably no less than 4,100. In order to counter this new strength, it seemed imperative to the commanders concerned that the BACKHANDER landing force be reinforced.

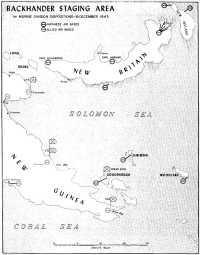

Map 22: BACKHANDER Staging Area, 1st Marine Division Dispositions, 18 December 1943

On 2 November, during a conference at 1st Marine Division headquarters attended by the division commander, Major General William H. Rupertus, Admiral Barbey, and Colonel Clyde D. Eddleman, Krueger’s G-3, the matter was considered at length. Under existing plans, the ratio of assault troops to defenders would be 1.8 to 1 if the 503rd landed and only 1.3 to 1 if weather prevented the drop. If an additional Marine battalion landing team was committed, the ratio would rise to 2 to 1 (or 1.7 to 1 without paratroops), a balance closer to the clear superiority experience demanded for an attacking force. Eddleman recommended to Krueger that a landing team of Combat Team B be employed at Tauali and that all of Combat Team C land east of the airfield. General Rupertus seconded this finding with proposals for several alternative landing schemes, one favoring the change endorsed by Eddleman. Conclusively, the ALAMO staff came up with a new estimate of the situation on 5 November that recommended an additional battalion be employed. A query from ALAMO headquarters to GHQ at Brisbane brought a quick reply that Krueger had full authority to use the battalion if he so desired.

In addition to getting a sufficient number of assault troops ashore at BACKHANDER, Krueger’s staff was gravely concerned about the possible need for reinforcement. To meet this contingency, they recommended that shipping to lift the remainder of Combat Team B to the target be available at its staging area on D-Day. The same requirement was stated for Combat Team A, then at Milne Bay and the unit of the 1st Division farthest from Cape Gloucester. Admiral Barbey was prepared to furnish the ships required, using LCIs to move Combat Team B and transports to shift Combat Team A to Oro Bay, where it could move on, should it prove necessary, in APDs and LCIs. Many of the vessels Barbey designated would have to do double duty; first at Gasmata, then at Gloucester.

With amphibious shipping heavily committed until late November to support Huon Peninsula operations, the time for rehearsal, training, and reoutfitting before DEXTERITY got underway was woefully short. The lapse of six days then figured between LAZARETTO and BACKHANDER landings gave planners little leeway, and tight scheduling for maximum shipping use made no provision for losses at Gasmata. Under the circumstances, General Krueger asked General MacArthur for permission to set back the landing date for LAZARETTO to 2 December. At the same time, in consideration of the delay in the completion of the Huon airfields and the increased demand for shipping, Krueger suggested a BACKHANDER D-Day of 26 December. MacArthur approved deferral of the landing dates for the two operations and eventually decided upon 15 and 26 December after additional changes in forces and objectives.

Even while the date for LAZARETTO was being altered, the need for undertaking the operation at all was being seriously questioned, particularly by Allied Air Forces.8 Kenney’s staff was swinging strongly to the opinion that the forward airstrip planned for the

Lindenhafen Plantation beachhead was not necessary to future air operations. Reinforcing this conclusion was the fact that long-range fighter planes would be in short supply until February 1944. Replacement and reinforcement aircraft scheduled to arrive in the Southwest Pacific had been delayed, and, in November, Kenney had to curtail daylight strikes on Rabaul to conserve the few planes he had. The Allied air commander could promise fighter cover over the initial landings at Gasmata, but nothing thereafter. The assault troops would have to rely on antiaircraft fire to fend off Japanese attacks. Perhaps the most disquieting news was that the enemy was building up his garrison at Gasmata, apparently anticipating an Allied attack.

With General Kenney reluctant to regard LAZARETTO as an essential operation and unable to provide aerial cover after it began, the Gasmata area lost its appeal as a target. On 19 November, following a conference with air, naval, and landing force representatives, the ALAMO Force G-3 concluded that carrying through the operation would mean “that we can expect to take considerable casualties and have extensive damage to supplies and equipment as a result of enemy bombing operations subsequent to the landing.”9 An alternative objective, one closer to Allied bases, less vulnerable to enemy air attack, and more lightly defended, was sought.

Generals Krueger and Kenney and Admiral Barbey met on 21 November to decide on a new objective. They chose the Arawe Islands area off the south coast of New Britain, 90 miles closer to Cape Gloucester than Gasmata. Kenney’s staff had considered placing a radar station at Arawe before the LAZARETTO project clouded and still was interested in the area as a site for early-warning radar guarding the approaches from Rabaul. The conferees agreed that Arawe would also be a good location for a motor torpedo boat base from which enemy barge traffic along the coast could be blocked. There is evidence that the Commander, Motor Torpedo Boats of the Seventh Fleet was less convinced of the need for this new base, but his objections were evidently not heeded at this time.10 A powerful argument in favor of the choice was the denial of the site to the Japanese as a staging point through which reinforcements could be fed into the Cape Gloucester area. Then, too, the diversionary effect of the attack might draw off defenders from the main objective.11

General MacArthur quickly approved the findings of his field commanders and confirmed the landing date they asked for, 15 December.12 On 22 November,

amended operations instructions for DEXTERITY were issued by GHQ cancelling LAZARETTO and substituting for it the DIRECTOR (Arawe) operation. An immediate benefit of the switch was a gain in shipping available for BACKHANDER and an increase in the number of troops ready for further operations. The suspected enemy garrison at Arawe was far weaker than that known to be at Gasmata, and the mission assigned the landing force was less demanding in men and matériel resources.

The LAZARETTO task force built around the 126th Infantry was dissolved and its elements returned to ALAMO Force reserve. A new task force, half the strength of its predecessor, was formed using troops released from garrison duties on Woodlark and Kiriwina. Named to command the DIRECTOR Force, which centered on the 112th Cavalry, was Brigadier General Julian W. Cunningham, who had commanded the regiment during the occupation of Woodlark.

The abandonment of LAZARETTO gave GHQ planners a welcome bonus of combat troops available for further DEXTERITY operations. Once the Japanese threat at Cape Gloucester was contained and both flanks of Vitiaz Strait were in Allied hands, the seizure of Saidor on the north New Guinea coast could follow swiftly. An outline plan for the Saidor operation issued on 11 December mentioned that either an RCT of the 1st Marine or the 32nd Infantry Divisions might be the assault element. Within a week, changes in the composition of the BACKHANDER Force had narrowed the choice to an Army unit.

On 17 December, impressed by the evident success of DIRECTOR operations, General MacArthur ordered preparations for the capture of Saidor to get underway with a target date on or soon after 2 January. Many of the supporting ships and planes employed during the initial landings at BACKHANDER would again see service at the new objective. ALAMO Force issued its field order for Saidor on the 22nd, assigning the 126th Infantry (Reinforced) the role of assault troops. Krueger saved invaluable preparation time by organizing a task force which was essentially the same as the one which had trained for LAZARETTO.

One aspect of the BACKHANDER plan of operations—the air drop of the 503rd Parachute Infantry—gathered opposition from all quarters as the time of the landing grew nearer. Krueger’s staff was never too enthusiastic about the inclusion of the paratroopers in the assault troops, but followed the outline put forward by GHQ. Rupertus was much less happy with the idea of having a substantial part of his force liable to be cancelled out by weathered-in fields or drop zones at the most critical stage of the operation.13 On 8 December, Allied Air Forces added its opposition to the use of the 503rd with Kenney’s DIRECTOR of operations stating that “ComAAF does not desire to participate in the planned employment of paratroops for DEXTERITY.”14 The air commander understood that a time-consuming plane shuttle with a series of drops

was planned, a maneuver which would greatly increase the chance of transports being caught by the expected Japanese aerial counterattack on D-Day. In addition to this consideration, Kenney found that the troop carriers needed to lift the 503rd would crowd a heavy bomber group off the runways at Dobodura, the loading point for the air drop. The displaced bombers would then have to operate from fields at Port Moresby, where heavy weather over the Owen Stanley Mountains could keep them from supporting the operation.

The stage was set for the change which took place on 14 December at Goodenough Island where MacArthur and Krueger were present to see the DIRECTOR Force off to its target. The two generals attended a briefing on the landing plans of the 1st Marine Division where Colonel Edwin A. Pollock, the division’s operations officer, forcefully stated his belief that the drop of the parachute regiment should be eliminated in favor of the D-Day landing of the rest of Combat Team B to give the division a preponderance of strength over the enemy defenders. Pollock’s exposition may have swung the balance against use of the paratroops,15 or the decision may have already been assured;16 in either event, the order went out the next day over Krueger’s signature changing the field order for BACKHANDER. The seizure of Cape Gloucester was now to be an operation conducted by a unit whose components had trained and fought together.

Training and Staging BACKHANDER Force17

For effective planning of DEXTERITY operations, General Krueger and the Allied Forces commanders had to strike a balance between the flexibility necessary to exploit changing situations and the exact scheduling required for effective employment of troops, ships, and supplies. The changes wrought in ALAMO Force plans were keyed, therefore, to the physical location of troops in staging and training areas, to the contents and replenishment potential of forward area depots, and to the number and type of amphibious craft available. Throughout the later stages of the planning for BACKHANDER, the variations in scheme of maneuver and number of troops employed were based upon a constant factor, the readiness of the 1st Marine Division for combat.

When the division left Guadalcanal on 9 December 1942, many of its men were walking hospital cases wracked by malarial fevers or victims of a host of other jungle diseases. All the Marines were bone tired after months under constant combat strain and a rest was called for. No more

perfect tonic could have been chosen than Australia.

Melbourne, where the division arrived on 12 January, became a second home to the men of the 1st. Fond memories of the city and of the warm reception its people gave the Marines were often called to mind in later years by those who served there. Rewarded in a hundred ways by its release from the jungles of the Solomons and a return to civilization, the 1st Division slowly worked its way back to health and battle fitness. Although at first as many as 7,500 men at a time were down with malaria or recovering from its ravages,18 the number dwindled as climate and suppressive drugs took effect.

A training program, purposely slow-starting, was begun on 18 January with emphasis during its initial phases on the reorganization and reequipment of units and the drill and physical conditioning of individuals. By the end of March, practice in small-unit tactics was the order of the day. Through April, May, and June, all men qualified with their new basic weapon, the M-1 rifle, a semi-automatic which replaced the bolt-action Springfield M-1903 carried by American servicemen since the decade before World War I. Nostalgia for the old, reliable ‘03 was widespread, but the increased firepower of the M-1 could not be denied.

In April and May, battalions of the 5th and 7th Marines practiced assault landings on the beaches of Port Philip Bay near Melbourne. One of the two ships used was a converted Australian passenger liner and the other was the only American attack transport (APA) in the Southwest Pacific. Sent over from Halsey’s area, the APA was assigned to Barbey’s command to give him at least one of the Navy’s newest transports for training purposes.19 With the help of the experienced Marines, VII Amphibious Force officers worked out a series of standing operating procedures during the exercises which would hold for future training and combat usage.

While it was in Australia, the 1st Division had no opportunity to use the variety of specialized amphibious shipping that had come into use since its landing on Guadalcanal. Most LSTs and LCIs were sent forward to Papuan waters as soon as they arrived from the States; the LCTs, which were shipped out in sections, joined the ocean-going ships as soon as they were welded together. In the combat zone, the landing ships were urgently needed to support the operations of New Guinea and ALAMO Forces. The Marines’ chance to familiarize themselves with the new equipment would come in the forward area where GHQ planned to send the division after it completed a summer of intensive field training in the broken country around Melbourne.

As a necessary preliminary to effective large unit training and operations, the division was organized into combat and landing teams on 25 May. Many of the supporting unit attachments were the same as those in regimental and battalion

embarkation groups already in existence. In terms of the general order outlining the assignments, the combat team was described as “the normal major tactical unit of the division,” and the landing team was “regarded essentially as an embarkation team rather than a tactical unit.”20 Many of the reinforcing units in the battalion embarkation groups would revert to regimental control on landing, and, similarly, the division expected to regain control very soon after landing of supporting headquarters and reserve elements included within regimental embarkation groups.

In mid-summer, while 1st Division units were either in the midst of combat team exercises, preparing to take the field, or squaring away after return, a Sixth Army inspection team made a through survey for General Krueger of the Marine organization. The Army officers came away much impressed, noting:–

[This division] is well equipped, has a high morale, a splendid esprit and approximately 75% of its personnel have had combat experience. The average age of its enlisted personnel is well below that in Army divisions. ... At the present time, the combat efficiency of this division is considered to be excellent. In continuous operations, this condition would probably exist for two months before declining. With rest and replacements between operations, it is believed that a better than satisfactory combat rating could be maintained over a period of six months.21

The inspection team expressed some concern about the substantial incidence of malaria in the division’s ranks, but made its finding of combat efficiency “Excellent” despite this. The very apparent high morale was attributed to the 1st’s experienced leadership, as all the division staff, all regimental and battalion, company and battery commanders had served on Guadalcanal.22 This pattern of veteran leadership was evident down through all ranks of the division with a good part of the infantry squads and artillery firing sections led by combat-wise NCOs.

The first echelons of the division to move northward to join ALAMO Force were the engineer and pioneer battalions of the 17th Marines. On 24 August, the engineers (1/17) sailed from Melbourne for Goodenough Island to begin construction of the division’s major staging area. The pioneer battalion (2/17) moved by rail to Brisbane, “where it drew engineering supplies, transportation, and equipment of the regiment, and stood by to load this material on board ship if a wharf labor shortage developed.”23 It departed for Goodenough on 11 September. The 19th Naval Construction Battalion, which served as the 3rd Battalion, 17th Marines, was working at the big U.S. Army Services of Supply (USASOS) base at Cairns, north of Townsville, and remained there under Army control until the end of October.

The formal movement orders were issued to the division on 31 August, setting forth the priority of movement of units and the amount and type of individual

and organizational equipment that should be taken. In general, 40-days’ rations, quartermaster, and medical supplies were to be loaded, as well as a month’s supply of individual and organizational equipment and 10 units of fire for all weapons. Reserve stocks of all classes of supply, and any material not available on first requisition to USASOS, were to be forwarded to the division’s resupply points. The troops themselves were to take only the clothing and equipment necessary to “live and fight,”24 storing service greens and other personal gear in sea bags and locker boxes for the better day when the pending operation would be over and a hoped-for return to Australia the reward for success.

The division’s main movement began on 19 September when Combat Team C finished loading ship and sailed from Melbourne in a convoy of three Liberty ships; its destination was Cape Sudest near Oro Bay. Three more convoys carrying the remainder of the division cleared Melbourne over the next several weeks, with the last Libertys pulling out with the rear echelons of division headquarters and Combat Team B on 10 October. The 18 ships used, hastily converted from cargo carriers, were far from ideal troop transports. Galleys, showers, and heads had to be improvised on weather decks, and the holds were so crowded that many men preferred “to sleep topside, fashioning out of ponchos and shelter halves and stray pieces of line rude and flimsy canvas housing.”25 Happily, the voyage had an end before the objectionable living conditions became a health hazard.

After its move, General Rupertus’ command was dispersed in three staging areas that corresponded, in nearness to the target, with the roles the combat teams were scheduled to play in BACKHANDER operations. Encamped at Cape Sudest was the main assault force, Colonel Julian N. Frisbe’s 7th Marines, suitably reinforced as Combat Team C. At Milne Bay, farthest from Cape Gloucester, was Combat Team A, centered on Colonel John T. Selden’s 5th Marines; Selden’s troops, scheduled for a time to be the assault force at Gasmata, were now ticketed as reserves for Gloucester. On Goodenough Island, Combat Team B, under Colonel William J. Whaling, and the remainder of the division moved into camps the 17th Marines had wrested from the jungle. On 21 October, ALAMO Force Headquarters joined the division on Goodenough, moving up from Milne Bay in keeping with General Krueger’s desire to keep close to the scene of combat. (See Map 22.)

Each division element, immediately after arrival in its new location, unloaded ship and turned to setting up a tent camp. Before long, combat training was again underway at Oro Bay and Goodenough with emphasis on jungle operations, a species of warfare all too familiar to Guadalcanal veterans. At Milne Bay, Combat Team A had to clear and construct its own camp area while providing 800-900-man working parties daily to help build roads and dumps in the base’s supply complex. Colonel Selden rotated the major labor demand among his battalions, giving them all a chance to work as a whole to finish their living area and get a

start on jungle conditioning and combat training.26

On 1 November, with the arrival of the Seabees of 3/17 at Goodenough, the organic units of the 1st Division were all assembled in the forward area. The Japanese attempted a lively welcome by sending bombers and scout planes over Oro Bay and Goodenough throughout the staging period; these raids, seldom made in any strength or pursued with resolution, caused no casualties or damage in Marine compounds and only slight damage to adjoining Army units. The enemy effort had nothing but nuisance value as far as stemming preparations for future operations was concerned, but it did give the Japanese a pretty fair idea of the Allied buildup along the New Guinea coast.

In order to give the troops assigned to DEXTERITY adequate opportunity to familiarize themselves with the landing craft they were to use, Admiral Barbey had to devise a system that would allow him to use a small number of craft to train a large number of men. There was no time to fit the construction of an amphibious training base on New Guinea, similar to those in Australia, into support plans for the move against New Britain. Five months was the lowest estimate of the time necessary to complete such an undertaking, and the men, materials, and ships necessary to support it could not be spared from current operations. On 16 August, Barbey recommended the establishment of a mobile training unit consisting of enough landing craft and supporting auxiliaries to perform the amphibious training mission in the forward area. Carpender and MacArthur both concurred in the recommendation, and the mobile group was organized with headquarters at Milne Bay.

Marines from all three 1st Division staging areas made their practice landings on the beaches of Taupota Bay, a jungled site on the north shore of New Guinea in the lee of the D’Entrecasteux Islands. At Taupota there was opportunity to put ashore enough troops, vehicles, and supplies to test landing and unloading techniques. On 22 October, 1/1 in two APDs and two LSTs lifted from Goodenough to the practice beaches. There the assault troops went ashore in LCVPs from the destroyer-transports and were followed by landing ships with a full deck-load of vehicles plus 40 tons of bulk stores. Since all of the division pioneers were attached to the 7th Marines at Cape Sudest, there was no experienced nucleus for the shore party. One LST took three hours to unload, the other four and a half, prompting VII Amphibious Force to observe that “unloading parties provided were quite inadequate and very little appreciation was shown for the necessity of getting the craft off the beach as quickly as possible.”27

The critique of the faults of this landing, together with a more comprehensive application of the newly promulgated Division Shore Party SOP,28 enabled 2/1, using the same ships and landing scheme

two days later, to halve unloading time. On 28 and 31 October, the 7th Marines mounting out from Oro Bay and Cape Sudest was able to land all infantry battalions and supporting elements in the pattern of assault waves coming from APDs, followed by LCIs with support troops, and LSTs with vehicles and bulk cargo. The unloading time per LST was cut to less than an hour by means of adequate troop labor details and the application of cargo handling techniques developed in training for the landings. Combat Team A was able to profit from this experience when the reinforced 5th Marines’ battalions made a series of trouble-free practice landings from LSTs and LCIs between 14 and 30 November.29

During the amphibious training period, Marine assault troops landed as they would at Cape Gloucester in ships’ boats, LCVPs and LCMs. No serious obstacles existed off the chosen beaches which could bar landing craft from nosing ashore, and the amphibian tractors organic to the 1st Division were reserved for logistical duties. That role promised to be quite important to the success of the operation. Extensive tests in the jungles that fringed the staging areas showed that the LVT could negotiate terrain, particularly swamp forest, that was an absolute barrier to other tracked vehicles, even the invaluable bulldozer. The cargo space of 1st Amphibian Tractor Battalion’s standard LVT (1) Alligator could hold 4,500 pounds, and that of the few newer, larger LVT (2) Buffaloes that were received a few days before embarkation could contain 6,500 pounds.30 The tests also revealed that the LVT was a splendid trail breaker for tractors, a fact that had immediate application in the plans for employment of artillery at Cape Gloucester.

In Combat Team C’s Oro Bay training area, Alligators were used successfully to smash a path through the jungle for 4/11’s prime movers and the 105-mm howitzers they towed. To distribute the weapons’ weight over a large area, truck wheels were mounted hub to hub with the howitzer wheels.31 The one-ton trucks assigned to haul 1/11’s 75-mm pack howitzers proved unequal to the task of following in the LVTs’ rugged trace, and the 11th Marines’ commander, Colonel Robert H. Pepper, took immediate steps to secure light tractors from the Army as supplementary prime movers for his three pack battalions.32 The potential of the LVTs was firmly demonstrated to the ALAMO Force artillery officer who watched them work in a swampy area of Goodenough on 4 December. He reported to the ALAMO chief of staff:–

Performance was impressive. Knocked over trees up to 8” in diameter and broke a trail through the densest undergrowth. The branches, trunks, and brush formed a natural matting capable of supporting tractors and guns. I believe that with a limited amount of pioneer work practically any jungle country can be traversed with artillery drawn by tractors if preceded by two LVTs.33

As this demonstration was being conducted, the movements to final staging areas had begun. On 3 December, a detachment of Combat Team B left

Goodenough for Cape Cretin near Finschhafen, followed on the 11th by the rest of the 1st Marines and its attached units. From this point nearest to the target area, the landing team assigned the role of taking and holding the trail block at Tauali, the 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines, and the rest of the combat team destined to follow the 7th Marines across the main beaches, would mount in separate convoys for D-Day landings. Accompanying Combat Team B was the Assistant Division Commander, Brigadier General Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr., and his staff.

Between 7 and 18 December, all elements of the division that would land with or under command of Combat Team C during the initial phase of BACKHANDER, moved from Goodenough to Cape Sudest. General Rupertus, the task force commander, shifted his CP to Oro Bay at this time, leaving only the division rear echelon on Goodenough. Colonel Selden’s Combat Team A at Milne Bay made ready to sail for Cape Sudest on D minus one (25 December) to be in position as division reserve to answer a call for reinforcements. The team was to move from Milne in transports and transfer at the Oro Bay staging area to landing ships for further movement to Cape Cretin. ALAMO Force placed a hold order on the commitment of one 5th Marines battalion (3/5) so that it might be used to seize either Rooke or Long Islands as the site for a sentinel radar guarding the overwater approaches to the main objective from the northwest. Besides this tentative mission, another possible employment of the battalion was as part of the reserve in support of the assault units of the 1st Division.

The major part of the BACKHANDER Force assembled in the staging area for the assault phase of the operation was organic to the 1st Marine Division. One unit, in fact, was peculiarly the division’s own, its air liaison detachment. Impressed by the need of a light plane squadron to handle reconnaissance and air spotting, the division commander’s personal pilot, Captain Theodore A. Petras, and the division air officer, Lieutenant Colonel Kenneth H. Wier, had recommended in early summer of 1943 that such a unit be formed within the division. General Vandegrift agreed and was able to persuade General MacArthur to provide the division with 12 Army L-4 Piper Cubs. When General Rupertus took over the 1st’s command, he endorsed the idea fully and directed Petras to organize the unit and run its training program.

Volunteers with flying experience were called for and 60 men applied; from this group, 12 pilots, 1 officer and 11 enlisted men, were selected. Mechanics for the Cubs were similarly chosen and the maintenance men who kept up Petras’ transport served as their instructors. For two and a half months before D-Day, the makeshift air force worked intensively to reawake flying skills and to learn with the artillery suitable techniques for air spotting of targets. The most serious problem faced was the lack of adequate air-ground communication; the radios available were unreliable and a system of visual signals was developed. For movement to Cape Gloucester, the planes were dismantled and loaded on board LSTs scheduled to arrive on D-Day.34

In addition to the force of light planes, General Rupertus also had a pool of landing

craft under his direct command, both elements which would give him greater flexibility in meeting combat emergencies or in taking advantage of sudden changes of fortune that might affect the Japanese defenders. The boat crews were not sailors, however, but Army amphibian engineers, members of a provisional boat battalion of the 592nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment. The engineers, manning LCVPs and LCMs, were products of a special training program in the States through which the Army anticipated and met some of the problems that arose in conducting amphibious operations. Used in strength first in the Lae-Finschhafen campaign, the engineers were prepared to move supplies of troops from ship to shore or shore to shore, to act as a shore party, to man beach defenses, and, in sum, to make themselves generally useful.35 At Cape Gloucester, since the Marines had their own shore party, the amphibian engineers provided only a part of their services, but these were of inestimable value.

A more usual attachment to BACKHANDER Force in Marine experience was the assignment of Colonel William H. Harrison’s 12th Defense Battalion to the operation. The rapid-firing 40-mm guns of the battalion’s Special Weapons Group would augment the fire against low-level attackers put up by Battery A of the division’s 1st Special Weapons Battalion. The searchlight battery and the 12th’s 90-mm Group would guard the beachhead from bombers making their runs above the reach of automatic weapons. A platoon of 155-mm guns from the Seacoast Artillery Group was to come in with the light antiaircraft elements of the battalion,36 while the remainder of Harrison’s artillery would arrive with the garrison force.

BACKHANDER Landing and Support Plans37

Throughout the evolution of BACKHANDER plans, the 1st Marine Division expressed its determination to preserve its tactical integrity as a unit and to place “an overwhelming force on the beach against a determined enemy.”38 The operation plan that finally governed the Cape Gloucester assault mirrored this concept of the division’s most efficient employment.

The tasks set General Rupertus’ force were threefold: to land in the Borgen Bay-Tauali areas, establish beachheads, and capture the Cape Gloucester airfields; to construct heavy duty landing strips at Gloucester as soon as possible and assist Commander, Allied Air Forces in establishing fighter sector, air warning, and radio navigational facilities; and to extend control over western New Britain to include the general line Itni River-Borgen

Bay, with patrols to investigate the possibility of developing an overland supply route to Gilnit village on the Itni. Within the airfield defense perimeter BACKHANDER Force was to establish, construction priority was assigned facilities to accomodate an Allied fighter-interceptor group.

Basically, the scheme of maneuver developed to capture Cape Gloucester called for simultaneous landings east and west of the airfields, each site about seven miles from the point of the cape itself. On GREEN Beach near Tauali, Lieutenant Colonel James M. Masters, Sr., would land his battalion, 2/1, and its attached units, seize a limited beachhead, organize it for defense, and hold it against enemy forces attempting to use the coastal trail to reach the airfields or to withdraw from them. On the opposite side of the cape, on a pair of beaches (YELLOW 1 and 2) near Silimati Point, Colonel Frisbie’s 1st and 3rd Battalions, 7th Marines would land in assault followed by 2/7, with the mission of seizing a beachhead, organizing it for defense, and covering the landing of the rest of the assault force.

Shortly after H-Hour, 3/1 would begin landing behind 3/7 on the westernmost beach, YELLOW 1. Once ashore, the battalion, resting its right on the coast, would attack west on a 500-yard front to seize the first of a series of phase lines designated to guide the attack toward the airfields. During the afternoon of D-Day, the remainder of Colonel Whaling’s combat team would land, assemble just outside the right flank of the beachhead perimeter behind 3/1, and prepare to attack west on order.

After landing, Combat Teams B and C were to retain a number of the units assigned to them under direct command, but a large portion of their strength was to revert to control of the force commander. The combat teams kept their close-in supporting weapons, tanks, and antitank guns, but lost their artillery and antiaircraft guns to the force. Each team also kept its attached engineer company, its scout platoon, and its detachments from the division medical and service battalions. Since its primary mission was defense of a beachhead perimeter in tangled jungle terrain, Combat Team C could not make best use of some of its attachments. Accordingly, the force shore party was reinforced by the military police, motor transport, and amphibian tractor units once assigned to Colonel Frisbie’s command. Similar attached units with Combat Team B remained under Colonel Whaling’s control to support the advance up the coastal road.

In planning the disposition and employment of field artillery, Colonel Pepper’s 11th Marines’ staff picked out the one open area of any extent within the chosen beachhead, a patch of kunai grass on the right flank with a good all-around field of fire, as the postlanding position of 4/11. The 4th Battalion’s 105-mm howitzers, in direct support of Combat Team B, could reach the airfield but also could fire on counterattacking enemy anywhere along the perimeter and its approaches. With the only good artillery position inside the beachhead going to 4/11, the 75-mm pack howitzers of the 1st Battalion landing in direct support of Combat Team C were left to “fend for themselves in an area that appeared fairly open with only scattered growth” near Silimati Point.39 Both

artillery battalions were assigned a platoon of LVTs to help them reach and maintain their firing positions in what was expected to be very rugged terrain. The 75-mm packs of 2/11, sailing and landing with Combat Team B, were to set up in what seemed a suitable area just off the coastal road outside the perimeter. While the field artillery landing on the YELLOW Beaches would revert from combat team to 11th Marines’ control, Lieutenant Colonel Masters on GREEN Beach was to keep command of Battery H of 3/11 as an integral part of his landing team. The 12th Defense Battalion’s Seacoast Artillery Group commander was to coordinate the fire of all weapons used against seaborne targets.

The antiaircraft units assigned to BACKHANDER Force were to come under Colonel Harrison of the 12th Defense Battalion as senior antiaircraft officer. Initially, he would also control air raid warning throughout the force, but this service would become a function of the Allied Air Forces’ Fighter Sector Commander, as soon as this officer landed and had his radar and communications in operation. The sector commander controlled all airborne Allied fighter units assigned to protect the Cape Gloucester area and, in addition, could order antiaircraft fire withheld, suspended, or put up in special defensive patterns through Harrison’s fire direction center.

The engineer plan for BACKHANDER operations gave primary responsibility for tactical support to Colonel Harold E. Rosecrans’ 17th Marines, with airfield repair and construction assigned to a base engineers group built around two Army engineer aviation battalions. In addition to the usual combat engineer tasks of construction, demolition, and repair, the lettered companies of 1/17, attached to combat teams, provided flamethrower teams to work with infantry against enemy fortifications. Colonel Rosecrans’ regimental Headquarters and Service Company, 1/17 (less Companies A, B, and C), and 3/17 formed a combat engineer group which was responsible for water supply, for construction, repair, and maintenance of roads, bridges, and ship landing facilities, and for any other construction task assigned. Through contacts made by officials of the Australia-New Guinea Administrative Unit (ANGAU) accompanying the task force, it was hoped that maximum use could be made of native labor in all engineer missions.

The 17th Marines’ 2nd Battalion, the division’s pioneers, formed the backbone of the shore party. Reinforced by two companies of replacements and the transport and traffic control units drawn from Combat Team C, the shore party under Lieutenant Colonel Robert G. Ballance was responsible for the smooth and effective unloading of all task force supplies. In order to expedite the job of getting bulk stores off LSTs, a system of overlapping dumps was planned, with each beached LST sending its cargo to its own class dumps, sharing with other ships only those on the flanks of its unloading area. Most of the supplies were mobile loaded on trucks to be run off LSTs to the dumps. In order to make mobile loading work, General Krueger’s headquarters assigned 500 reconditioned 2½-ton trucks to temporary use of BACKHANDER Force, with the drivers recruited from an Army artillery battalion not actively committed to ALAMO operations. The trucks were to make a round trip circuit from LST to dump and return with the ships to the staging areas. All tractors and trucks organic

to 1st Marine Division units, that were not needed for tactical purposes in the early stages of the landing, were to report to the shore party for use in moving supplies.

Assault troops headed for Cape Gloucester were to carry 20-days’ replenishment supplies of all types as well as three units of fire for task force weapons. The garrison troops would bring in 30-days’ supplies, three units of fire for ground weapons, and five units of fire for antiaircraft guns. In order to insure a smooth flow of supplies to Cape Gloucester, and the eventual maintenance of a 30-day level there, the 1st Division established a control system for loading and resupply. At Cape Sudest on Oro Bay, the main supply base for BACKHANDER operations, an officer from the division quartermaster’s office acted as forwarding officer, his main duty to insure the movement of essential matériel to the combat zone. Supplies and personnel needed at the objective were to be funnelled through a regulating officer, who established priorities for loading and movement, and a transport quartermaster, who planned and supervised the actual loading.

Admiral Barbey’s allocation of shipping to lift the BACKHANDER Force made the LST the main resupply vessel. With mobile loading of most bulk stores, a practiced shore party, and a dump plan that promised swift clearance of ships’ cargo space, the amphibious force commander felt that he could risk the vulnerable LSTs in the combat area. The schedule of arrival and departure of the hulking landing ships, often dubbed Large Slow Targets by crew and passengers, was kept tight to lessen exposure to enemy air attack. Since the logistic requirements of shore-to-shore operations meant that many vessels would make repeated trips to the YELLOW Beaches, the speed of unloading promised to pick up as shore party and ships’ crews became more experienced.

The LST had a prominent part, too, in the medical evacuation plan for BACKHANDER. The flow of casualties during the first days of the operation would be from landing force units through the evacuation station run by the naval element of the shore party. Men hit during fighting immediately after H-Hour would be sent out by the first landing craft available to APDs riding offshore; once landing ships had beached, the wounded would be carried on board over the ramps into special areas set aside for casualty treatment. Medical officers and corpsmen from Seventh Fleet were assigned to all ships used as transports for the assault forces. To give the best possible care to the seriously wounded on the return voyage to New Guinea, Army surgical-medical teams were present on one LST of every supply echelon. At Cape Sudest, an LST equipped as an 88-bed hospital ship was ready to receive casualties from Cape Gloucester and pass them on to base hospitals ashore when their condition warranted. As soon as the combat situation permitted, casualties requiring less than a month’s bed care and rest would be kept at Cape Gloucester in garrison force hospitals.

The total of shipping assigned to BACKHANDER support was not impressive in comparison to the large number of vessels needed to land and protect a division in the Central Pacific. There was no need, however, for massive invasion armadas. Because of the wider range of objectives that the large islands of the southern Pacific gave them, MacArthur and Halsey seldom had to send their assault

troops against heavily fortified Japanese positions. This fortunate circumstance shaved the requirement for naval gunfire support ships, or at least gave the operations against Central Pacific fortress islands a higher priority of assignment. Similarly, the availability of land-based Allied air in significant force made the use of carrier planes wasteful when the naval pilots could be better employed against other targets.40

In total, Admiral Barbey as Commander, VII Amphibious Force assigned himself as Commander, Task Force 76, the BACKHANDER Attack Force, 9 APDs, 33 LSTs, 19 LCIs, 12 LCTs, and 14 LCMs to transport, land, and maintain the assault and garrison troops. The LCTs and LCMs plus five LCIs were assigned to the Western Assault Group (GREEN Beach) under Commander Carroll D. Reynolds; the rest of the LCIs, the APDs, and the LSTs were part of the Eastern Assault Group scheduled for the YELLOW Beaches. Admiral Barbey commanded the ships at the main landing as well as the naval phases of the whole operation.

For fire support duties, Commander Reynolds had two destroyers and two rocket-equipped amphibious trucks (DUKWs) carried in LCMs. To cover the landings on the eastern side of Cape Gloucester, Barbey had 12 destroyers in addition to his flagship and two rocket-firing LCIs.41 Escorting and supporting the attack force would be TF 74 under Vice Admiral V. A. C. Crutchley, RN, who had two Australian and two American cruisers with eight destroyers. The bombardment plan called for TF 74 to guard the approach of the main convoy against surface attack, to shell the airfield area before and immediately after the landing, and to retire westward when released by Barbey to take part in further operations.

All air units supporting the Cape Gloucester landings came under Brigadier General Frederick A. Smith, Jr.’s 1st Air Task Force with headquarters at Dobodura. From first light on D-Day, a squadron of fighters would escort the Eastern Assault Group to the target, with three squadrons successively covering the landings, and a fifth screening the planned retirement in midafternoon. Several destroyers in the attack force, including the Conyngham, had the special communications equipment and trained personnel to act as fighter director ships. During the time the main convoy was in the Cape Gloucester area, fighter control would remain afloat. Bomber control was a function of the Army’s 1st Air Liaison Party, part of BACKHANDER Force, which was to land with General Rupertus’ headquarters, establish contact with Dobodura, and direct aerial support of ground operations.

In the hour immediately preceding H-Hour, high-level bombing by five squadrons of B-24s would hit defensive positions back of the YELLOW Beaches while destroyers shelled the same target area. When naval gunfire was lifted, three squadrons of B-25s would streak across the coast bombing and strafing the immediate beach area, while a fourth squadron blanketed a prominent hill behind the beaches with white phosphorus bombs. At the same time, across the cape, another medium bomber squadron was slated to bomb and strafe GREEN Beach defenses before 2/1’s landing craft touched down.

On overhead standby during the initial landings would be four squadrons of attack aircraft; if they were not called down, these A-20s would hit targets south and east of the airdrome before returning to base. Later on D-Day morning, both a heavy and a medium bomb group would attack enemy bases and routes of approach along the southern coast. Nine squadrons of B-24s and four of B-25s that took part in the morning missions were to refuel and rearm immediately after landing at their home fields on New Guinea, and strike again in the afternoon at enemy installations west of the beachhead.

As the time of the main landings at Cape Gloucester neared, the Japanese defenders of New Britain were increasingly alert to the probability of Allied attack. The enemy commanders at Rabaul, however, could only guess where and in what strength the assault would come. Cape Gloucester’s airfields seemed a logical main target but so did Gasmata’s, and there were a number of lesser bases on both coasts that had to be considered and defended. The terrain of the island itself may perhaps have played the largest part in determining the ALAMO Force objectives and Eighth Area Army’s countermoves.