Chapter 16: The Drive to the East

Developing an East Front

Little affected by the bubbling, boiling political pots in Washington, London, North Africa, Italy, and Germany, little concerned with AFHQ’s plans for the invasion of the Italian mainland, General Alexander’s American, British, Canadian, and French soldiers continued their fight to clear Sicily. The arena of battle had shifted from the lowlands of the southeast corner to the mountainous Messina peninsula.

The Provisional Corps’ spectacular advance to Palermo completely overshadowed General Bradley’s II Corps maneuvers which, like those to the south, had also kicked off on 19 July. (See Map VIII) Enna, perched high on a mountain, dominated by the ruins of a large feudal castle, fell without a struggle, its importance to the Germans nullified by the advance of the 1st Canadian Division on Leonforte (which fell on 23 July) and the breakthrough by the 45th Division toward the north coast.

Matching the rapid advance of the Provisional Corps to Palermo, General Middleton’s 45th Division started its move for Palermo on the evening of 19 July. With the 180th RCT spearheading the advance northwest along Highway 121, the Americans overcame the Italian roadblock at Portella di Reccativo and made a nineteen-mile advance on the 20th. By the morning of 22 July, the 180th RCT was in the small town of Villafrati, only twenty-two miles from Palermo, and had patrols probing the outskirts of that port city. But the change in boundary, which gave the Provisional Corps the use of Highway 121, diverted the division’s main effort from Palermo to the north coast town of Termini Imerese, thirty-one miles east of Palermo. Accordingly, General Middleton sent his remaining two combat teams, the 179th and 157th, swinging north from Highway 121. At 0900 on 23 July, the 157th RCT reached the north coast road—Highway 113—at Station Cerda, five miles east of Termini Imerese. There the regiment turned left and right and cleared a stretch of the highway. Termini fell without a struggle, but a battalion moving eastward met Group Ulich, part of the newly arrived 29th Panzer Grenadier Division, just west of Campofelice. Though the battalion, aided by a company of tanks, managed to clear Campofelice, heavy enemy artillery and small arms fire coming from the ridge line across the Roccella River brought the Americans to a halt.1

On the 45th Division right, the 1st Division advanced from Enna in a far less spectacular, less rapid fashion because of greater opposition. Group Fullriede’s withdrawal from its westward facing salient southwest of the city during the evening of 19 July had not gone unnoticed, and General Allen sent the 26th Combat Team in pursuit. By then, the German battle group had passed through an Italian roadblock at Alimena and was side-slipping into a new east-west defensive line along Highway 120 from Gangi to Sperlinga. Facing south, these troops, according to the expectation of General Rodt, the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division commander, would prevent an American sweep around his division’s right flank. Although a small gap was still open in the center of his line, his left flank was secure, for Group Ens had withdrawn slowly from Canadian pressure east of Enna and had finally made contact with the Hermann Göring Division’s right flank near Regalbuto.

For the first time since the invasion, the two major German fighting units on the island had made physical contact. The gap which had existed in the center of the Axis front since 10 July was closed.2

Shortly before midnight on 20 July, the 2nd Battalion, 26th Infantry, led off the 1st Division’s advance on its new axis, the secondary road which wound through rough, mountainous terrain almost due north from Enna to Petralia. Pushed on by its aggressive commander, Lt. Col. Darrell M. Daniel, the 2nd Battalion moved into Alimena at 0500 the following morning. There, the Italian Group Schreiber made its final appearance. Sadly reduced by ten days of fighting and the loss of units at Portella di Reccativo, the Italian unit collected the remnants of an infantry battalion and a cavalry squadron north of Alimena to counterattack the 26th Infantry’s battalion. But American light tanks, which had been supporting Daniel’s battalion, spotted the concentration and, roaring down the road from Alimena, blasted into the Italian formation with all guns blazing. This dashing attack proved too much for the sorely tried Italians. Leaving most of their equipment behind, the Italians scattered into the surrounding hills and were seen no more. A few other Italians, hiding in the buildings of Alimena, proved more difficult to handle, and it was not until late afternoon that Colonel Daniel could report that the last of the enemy soldiers had been flushed out of basements and other hiding places.

The light tanks pushing on along the road to Petralia soon ran into direct enemy artillery fire covering a blown bridge just south of Bompietro, halfway to Petralia. The Germans, fearful that the 1st Division would move east from Alimena cross-country through the hills to Nicosia and into the gap which existed between the two battle groups, had deployed a provisional group at this point the previous afternoon to plug the hole.

It took until noon the next day, 22 July, before supporting 1st Division engineers could repair the bridge. Then, after a concentration by three artillery battalions, the 1st and 3rd Battalions, 26th Infantry, attacked across the small stream. Group Fullriede’s outposts put up stiff resistance—“the enemy resisted stubbornly, and, for the second time in Sicily, showed

Southern approach to Enna

artillery strength.”3 It was this German artillery, and the difficult terrain, that slowed the advance. The tanks were road-bound. The infantrymen were pinned down until the tanks could move forward to knock out at least some of the opposing guns. It was not until 1900 that the tanks managed to get through Bompietro with the 3rd Battalion, 26th Infantry, hard on their heels.

With Bompietro taken, General Allen leapfrogged the 18th Combat Team to continue the push on Petralia, and to open a hole through which the 16th Combat Team, still at Enna, could move to the north coast.4 For this was still the mission of the 1st Division, even though it had been temporarily diverted by the need to clear up the Enna area. With Enna in hand, the division could move to the north coast at Cefalù, paralleling the British 30 Corps advance. Near midnight, 22 July, the 1st and 2nd Battalions,

Leonforte

18th Infantry, dismounted from trucks at Bompietro, and moved through the 26th Infantry on the road to Petralia. Just before 0900, 23 July, after a stiff fight along the southern slopes of the high ground overlooking Petralia, the 2nd Battalion, 18th Infantry, together with two companies from the 1st Battalion, entered the town. Immediately, Colonel Smith, the combat team commander, started his battalions east along Highway 120 toward Gangi to block the secondary road which leads northward toward Cefalù, the route the 16th RCT was to follow to the north coast. This was done by late afternoon.5

But Petralia proved to be as far to the north as the 1st Division would go on its drive. The division would not be given a chance to reach the Tyrrhenian Sea as had the 45th Division farther west, for the Seventh Army axis of advance was changed again, this time to the east. On 20 July, General Alexander had

issued new instructions to General Patton. Upon reaching the coast north of Petralia, Seventh Army would send strong reconnaissance patrols eastward along the two main east-west highways left uncovered by the Eighth Army’s shift of its western axis of advance. These were the north coast road and Highway 120 through Sperlinga, Nicosia, and Troina. Thus, General Alexander changed the boundary between the two Allied armies. From its previous location running due north paralleling Highway 117, the new boundary ran due east between Highway 120 and the road serving as the British 30 Corps axis of advance. If possible, General Alexander continued, the Seventh Army was to follow up these reconnaissance forces in strength. Apparently, then, General Alexander intended to make Palermo the Seventh Army main base of supply, and to bring at least a part of the Seventh Army on line with the Eighth Army. General Montgomery concurred in the need for Seventh Army assistance.

Except for the assignment of the two northern roads to the Seventh Army, General Alexander’s 20 July directive amounted to little more than a modification of his 18 July directive. It did not indicate his intention of throwing the Seventh Army full tilt against the Axis forces in the Messina peninsula. General Montgomery’s attempt to break through the enemy lines on the east coast was still in process, though getting nowhere, when Alexander published his new order. The Army group commander apparently still hoped that Montgomery’s push would be successful. The directive did nothing to the U.S. II Corps plans, except to add two more roads to worry about. General Bradley’s mission of going to the coast “north of Petralia” remained; the directive merely moved the point at which the north coast was to be reached from Campofelice east to Cefalù.6

Montgomery’s decision on 21 July to bring over the British 78th Division from North Africa to reinforce a new push around the western slopes of Mount Etna, his calling off of attacks by the British 13 Corps at the Catania plain, and his previous shifting of the British 30 Corps main axis of advance from Highway 120 farther south to Highway 121, indicated to General Alexander that the Eighth Army alone was not strong enough to drive the Germans from the Messina peninsula.

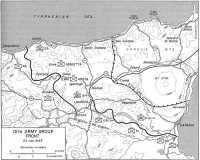

Just two days later, on 23 July, and after the capture of Palermo, General Alexander abandoned his scheme for a cautious, exploratory probing by the Seventh Army. Patton was now to employ his maximum strength along the two roads Alexander had given the Americans on 20 July. General Alexander had finally decided to place the Seventh Army on equal footing with the Eighth in order to finish off the remaining Axis forces. In other words, Messina was no longer solely an Eighth Army objective; Messina was now up for grabs.7 Map 3)

Map 3: 15th Army Group Front, 23 July 1943

Stopping the 1st Division drive for Cefalù at Petralia, and pivoting on the division, General Bradley began shifting the II Corps axis of advance to the east. General Patton had said that “the British have the bear by the tail in the Messina Peninsula and we may have to go in and help.”8 He therefore bolstered II Corps, to which he assigned the entire Seventh Army front. He stripped the Provisional Corps of the French 4th Tabor of Goums (which had performed well with the 3rd Division since its landing in Sicily on 14 July); the 9th Division’s 39th Infantry and its attached 34th Field Artillery Battalion; and other artillery units—and sent them scurrying eastward.9 General Patton also called for the remainder of General Eddy’s 9th Infantry Division to come over from North Africa because the 2nd Armored Division would be less useful in the mountainous terrain of northeastern Sicily and because both the 45th Infantry and 82nd Airborne Divisions would shortly have to be relieved to prepare for the invasion of Italy. General Eddy, a Regular Army officer since 1916, had led the

9th Division throughout the North African campaign, and would bring a tried fighting outfit to the Seventh Army for the final phases of the Sicilian operation.10

The news of Mussolini’s overthrow did not evoke much enthusiasm among the members of the Seventh Army’s front-line units. The soldiers did not believe it had really happened, and the news, if true, appeared to have little effect on reducing the scale of enemy resistance. If anything, the enemy seemed to be fighting more fiercely than ever to hold his mountain strongholds.11

Axis Reactions

Outwardly, with the fall of Mussolini, nothing had changed in Italy’s military policy or in the conduct of operations on Sicily. In reality, a profound change had taken place. The change did not stem from Rome, where Marshal Badoglio’s proclamations announced the continued vitality of the German alliance. Rather, the change stemmed from Hitler’s headquarters in far-off East Prussia.

Here, on 25 July, news of Mussolini’s dismissal led the angry Führer, among other things, to take drastic steps to save his embattled forces on the island. He excitedly told Jodl to evacuate all German personnel immediately from Sicily—take out the men, leave all the heavy equipment behind; move troops into northern Italy; occupy the mountain passes on the northern border; maintain firm control of the Italians; occupy Rome; capture the King, Badoglio, the Crown Prince, and other high-ranking officials; let the Germans take over the Italian Government; and find Mussolini and liberate him.

Relieved when he remembered that only part of the 1st Parachute Division had crossed into Sicily, he insisted that all the troops had to be taken out. What happened to their matériel did not matter in the least. “Everything will have to be done so fast,” Hitler said, “that the entire movement will be completed in two days—perhaps only one.” Warned by Jodl that no more than 17,000 men could be ferried over in one day under normal conditions, Hitler burst out with: “Well, they’ll have to crowd together. Do you remember how it was at Dunkerque? Is it not ridiculous to think that our Navy cannot ferry these men over such a small piece of water in two—nay in one day—provided the matériel stays behind?”

In closing the discussion, Hitler reminded Jodl of an important point. “Of course,” he said, “we will have to continue the game as if we believed in their [the Italians] claim that they want to continue [fighting].” To which Jodl agreed: “Yes, we will have to do that.” From then on, the Germans would mask their activities behind a cloak of secrecy.12

That night, General Jodl sent a teletype ordering Kesselring to evacuate Sicily. Since Jodl did not dare to entrust detailed instructions to conventional means of communication, he dispatched a personal representative to Rome to brief Kesselring on his role in Plan ACHSE.13

More detailed information and the repeated Italian declarations of continued cobelligerence mollified Hitler. He changed his mind on immediately evacuating the German troops from Sicily. The final evacuation would be delayed as long as possible.14

In Sicily, General Guzzoni was certain that the Allies would not invade the Italian mainland until after Sicily had first been subdued. Thus, the Sixth Army commander saw his mission as postponing the Allied conquest of the island as long as possible. If he received substantial reinforcements, he might even return to the offensive.15

But by then the command relationships in Sicily had changed. General Hube had committed elements of the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division along the north coast on 22 July, when he had nominally had tactical control of only the eastern half of the front. The commitment deployed German troops all along the front, from the eastern to the northern coast of Sicily. Since the Italian troops had lost almost all their combat effectiveness, the German troops had become the mainstay of the defense of the Messina peninsula.

On that same day, Hube had informed Guzzoni that he wanted tactical control of all the ground forces on the entire front. Guzzoni refused for two reasons. First, this arrangement would deal a severe blow to Italian prestige. Second, Guzzoni realized that Hube had developed a different concept of defense—one that he, Guzzoni, could not approve.16 Whereas Guzzoni still hoped eventually to regain the initiative, he suspected, and rightly that Hube had no intention of ever mounting a major counterattack—even though the situation had become somewhat stable by 21 July with the British advance on Catania stopped. The shift of the British main effort from Catania to Regalbuto and Leonforte and the highway system west of Mount Etna indicated a dispersal of effort. Withdrawal of the Axis forces from the invasion front and from western Sicily to the northeastern corner had been generally completed, except for some 15th Panzer Grenadier Division outposts in the northern sector. British attempts to break through would therefore meet solid opposition. Thus far, the American forces, still some distance west of the main defense line, constituted no immediate threat.

Guzzoni considered it feasible to defend northeastern Sicily on what the Italians and Germans commonly designated as the main line of resistance, a line from south of Catania to Santo Stefano di Camastra. He expected to hold this line long enough to gain enough time to build up the Etna line—from Acireale to San Fratello. In order to save those troops still west of

the main line of resistance Guzzoni on 21 July ordered both the XIV Panzer Corps and the Italian XII Corps to withdraw any outposts in the northern sector. He considered the troops on Sicily and those earmarked to arrive in the near future adequate not only to hold the line but also to form a reserve for a counterattack to regain the initiative, if only temporarily. What he needed was to keep together as a unit the newly arriving 29th Panzer Grenadier Division, rather than dissipate its strength by commitment in driblets.

But Hube refused to withdraw the northern outposts. He even committed a part of the new German formation on the northern coast. Quoting Hitler’s well-known doctrine of holding every foot of ground, Hube disclosed that no German commander would withdraw except under overwhelming pressure. These actions put an end to any intentions Guzzoni had to return to the offensive, even before it became painfully evident that Italian reinforcements were not going to be sent to Sicily. And although Guzzoni was still nominally in command of all tactical operations on Sicily, the preponderance of German over Italian combat troops on the island prompted him to bow to Hube’s decisions.17

On the other hand, General Hube’s actions were dictated by sound tactical reasons. He wished to give those German troops escaping from Palermo a chance to reach the Messina triangle. He also wanted to prevent the American Seventh Army from getting around the right flank of the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division and rolling up the entire Axis line. In accordance with the mission given him when he was sent to Sicily, Hube’s intentions were to execute an orderly withdrawal from the island, to include local counterthrusts but no major counterattack operations. The purpose of the entire operation was to gain time and to save German manpower for the expected future battles on the Italian mainland.

The Seventh Army’s arrival on the north coast on 22 July completely changed the situation. Except for remnants of Italian divisions, nothing stood in the way of an American drive on Messina via the north coast road. Experience had shown that Italian coastal units could not be depended on. The 15th Panzer Grenadier could not further stretch itself to cover the north coast road. Up to this time, the eastern and central sectors of the front had swallowed up all Axis reinforcements arriving on the island. To prevent an American breakthrough on the north, then, was the reason Hube had committed the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division.18

Convinced that a dual or vague command organization was detrimental to the future conduct of operations, Guzzoni settled for a compromise. In a conference on 25 July, he and Hube agreed, subject to the approval of their respective higher headquarters, that Guzzoni would nominally retain the over-all tactical command but with the tacit understanding that Hube would henceforth conduct the defense of the land front.19

The political upheaval in Rome having prevented an immediate reply to Guzzoni’s

and Hube’s joint proposal, Hube took over the actual conduct of ground operations on Sicily. He continued to discuss plans and decisions with Guzzoni and the Sixth Army staff directly or through the German liaison officer, General von Senger. And he tried to create the impression that the Germans on Sicily intended to fight to the bitter end. Guzzoni saw through the deception, but he was realistic enough to accept the situation. Though Guzzoni remonstrated with Hube against some of the latter’s decisions, he accepted German preeminence.

Nicosia

Hube’s assumption of real command and his employment of German divisions brought to an end the rapid advances of the Seventh Army. Oriented eastward, the II Corps would face difficult terrain and a most tenacious foe, highly skilled in the conduct of defensive operations.

The II Corps was to advance toward Messina along two separate axes: Highway 113 along the north coast, and Highway 120 through Nicosia, Troina, Cesarò, and Randazzo. Between the two major axes of advance, and parallel to them, ran the Caronie Mountain chain, the highest mountains on the island except Mount Etna. Extremely rugged, not flattening out to any appreciable degree until just west of Messina, the mountain chain had practically no road net save the four roads that crossed it in a general north-south direction.

The north coast axis of advance—Highway 113—skirted the rim of what resembled a washboard, created by numerous short streams flowing down from the mountain crests at frequent intervals to empty into the sea. The streams themselves were obstacles to advance, but high, steep ridges separating the stream were even more formidable and created positions of great natural strength. In addition, those ridges over which the four transverse roads ran also provided significant defensive lines. The coastal highway itself followed a narrow level belt between the ridge ends and the beaches At some places where the ridge ends came flush to the Tyrrhenian Sea, the road lay bracketed into the cliff directly above the surf. In one instance—at Cape Calavà (east of Cape Orlando)—the road swung past the point through a short tunnel. The coastal railroad from Palermo to Messina also followed the beach line, usually running between the highway and the sea crossing the streams on iron bridges, tunneling frequently through the ridges. Though exposed to attack from the sea the coastal highway offered defenders a series of good positions.

The other axis of advance—Highway 120—passed along the southern slopes of the Caronie Mountains. The road was narrow and crooked, with steep grade and sharp turns. In many places, heavy vehicles had to stop and back up in order to negotiate a turn. Like the coastal region, the mountainous area would provide a determined enemy with numerous ideal defensive positions. But unlike the north coast road, which lay exposed to seaborne assault, the mountains dominated Highway 120 on both sides.

The highland divide between the axes of advance would also contribute a special feature to the campaign in the Messina peninsula. Because the divide contained some of the most rugged and inaccessible terrain in Sicily, and because its slopes dominated the two major east-west arteries the mountain chain would separate the

Caronia Valley, typical of the rugged terrain in the Caronie Mountains

Gangi, with Mount Etna in the distant background

American forces advancing along the roads except at lateral roads, thereby precluding mutual support. Supply problems would be greatly magnified. The II Corps advance toward Messina would proceed over two distinct battlegrounds.

In order to establish a solid front before pushing on to the east, General Bradley first brought the 45th Division on line with the 1st Division while keeping the momentum of the latter’s attack. The 45th Division had come out on the north coast near Termini Imerese, and though it immediately turned toward the east, its front line was fifteen miles behind the 1st Division at Petralia. Until the 45th Division came up with the 1st Division, the II Corps would exert unequal pressure and enable the Germans to shift forces from one highway to the other to counter the two distinct American thrusts. The 91st Reconnaissance Squadron filled the gap between the 1st Division and the British 30 Corps on the right, but because General Bradley was again concerned about the Enna situation, he held the 16th RCT in corps reserve to counter a sudden Axis movement against his right flank. (Map 4)

General Allen brought forward the

Map 4: II Corps Advance, 24–31 July 1943

26th RCT and passed it through the 18th RCT east of Petralia on the morning of 24 July to take Gangi and the high ground beyond, then Sperlinga, just three miles from Nicosia.20

To cover this movement, the 18th Combat Team, late in the afternoon of 23 July, dispatched a company of infantry to the high ground southeast of Gangi. But before the company reached its objective, the regimental reconnaissance platoon moved into Gangi and found the

town clear of Germans. Group Fullriede had pulled its outposts back toward the main defensive line extending in an arc forward of Nicosia.

The 26th Infantry, after clearing the Bompietro road junction, pushed toward Gangi, straddling Highway 120 with a two-battalion front. Against light and intermittent artillery fire, the 1st Battalion moved north of the road toward Hills 825 (Monte Cannella) and 937 (Monte Caolina), while the 3rd Battalion headed for Hill 937 south of the road. When the 1st Battalion commander, Major Grant, reported Hill 825 nothing more than a big, barren slab of rock, impracticable to occupy, which the battalion could cover from high ground then held farther to the west, the combat team commander, Colonel Bowen, agreed that it was not necessary to take it. Though the 2nd Battalion commander, Colonel Daniel, made a similar report on Hill 937, Colonel Bowen directed him to secure the objective because Bowen wanted to push the 3rd Battalion around to the right and then cross-country directly into Nicosia, eight miles away. Daniel complied, and sent Company G to occupy the hill, one platoon of which reached the crest near midnight.

Daybreak of 25 July brought heavy enemy artillery fire across the entire 26th Infantry’s front. General Rodt had reinforced Group Fullriede during the night with troops that had just returned from the eastern sector. With this added strength, Colonel Fullriede sent a battalion of infantry to retake Hill 937. The American platoon outposting the crest, its leader a casualty, withdrew and rejoined the rest of the company at the western base of the hill. Disturbed by the failure to hold Hill 937 without a fight, Colonel Bowen ordered the 2nd Battalion to “work hard on it—get it back.”21 As Generals Allen and Roosevelt began pressing Bowen to retake the hill, Bowen, in order to relieve some of the pressure on the 2nd Battalion, directed the 1st Battalion, north of the road, to move forward and occupy Hill 825, even though Major Grant felt “there is no place to put anyone if we did have it.”22 Bowen also directed the 3rd Battalion to swing around the right of Hill 937 and pinch the Germans between the other two battalions.

Regaining the hill in the early afternoon, two companies of the 2nd Battalion began a short-range, murderous fire fight with the Germans, who withdrew just off the crest down the eastern slope. German and Italian artillery fire raked the hilltop, but the two American companies stood firm. By this time, Brig. Gen. Clift Andrus, the 1st Division’s artillery commander, had six artillery battalions plus two 155-mm. gun batteries firing in support of the 26th.23 As the 3rd Battalion came almost in line with the hill and turned toward the highway to take Hill 962 (Monte Barnagiano) in rear of the Germans on Hill 937, the Germans pulled away from this enveloping threat, and just before midnight, the 3rd Battalion pushed onto Hill 962.

The enemy was far from finished. Instead of hitting with a counterattack, then pulling out when American counterpressure became strong, the German reaction to the capture of Hill 962 was as strong

as against the loss of Hill 937. When Colonel Bowen, on 26 July, sent the 1st Battalion to Hills 921 and 825, eight hundred yards farther east, the Germans knocked the assault elements back to their starting line. South of the road, the Germans threw the 3rd Battalion off Hill 962, to start a seesaw battle, with Germans and Americans in alternate possession of the crest. Hill 962 soon became a no man’s land, with Germans on the eastern slopes, Americans on the western, and artillery controlling the top. Not until evening did the 3rd Battalion, with support from a battalion of the 16th Infantry, finally gain full possession of Hill 962.

General Bradley had released two battalions of the 16th Infantry from corps reserve that morning to enable General Allen to make a double envelopment of Nicosia. With the 26th Infantry apparently stopped on Highway 120 and the Germans showing no signs of giving up their positions around Sperlinga and Nicosia, General Allen that afternoon sent the two battalions of the 16th Infantry south of the highway and around Hill 962 toward Sperlinga. The 18th Infantry, north of the highway, was to swing past the 26th Infantry, take high ground north of Sperlinga and cut Highway 117, the lateral road through Nicosia, then move south to assist the 16th in clearing Nicosia and Sperlinga. The 91st Reconnaissance Squadron was to continue roving in the gap between the two armies, the 4th Tabor of Goums was to work on the left of the 18th Infantry. In explaining his attack plan, General Allen said, “Had we kept up just a frontal attack, it would have meant just a bloody nose for us at every hill.”24

The envelopment started at 1600, 26 July, as the 26th Infantry fought off renewed German counterattacks; the approach of darkness prevented more than a slight advance. Next day, 27 July, the 16th RCT south of the road was stopped cold in its drive on Sperlinga and Nicosia. North of the highway, while one battalion of the 18th Infantry cleared the two hills that had given the 26th Infantry so much trouble, another battalion, aided by the Goumiers, swung farther north to the approaches to Monte Sambughetti, a towering hill mass 4,500 feet high. An infantry company pushing up the hill took 300 Italian prisoners, and battalion patrols moved farther to the east and cut Highway 117.

Trying to jar the Germans loose from their positions forward of Sperlinga and Nicosia, General Allen ordered thirty-two light tanks from the 70th Tank Battalion, plus a platoon of tanks from the 753rd Medium Tank Battalion, to sweep south to the highway in front of Hill 825, coming out near Hill 962. The light tanks deployed at 2030 that evening and, covered by the mediums, roared down to the highway, where they “sprayed for miles around for at least ten or fifteen minutes before receiving artillery fire” and withdrawing. The sweep cost three light tanks and six casualties, but it gained one German antitank gun and bolstered the morale of the American infantrymen on the surrounding hills. By then, the German forces on the Nicosia front had decided to withdraw.

The German withdrawal during the night of 27 July opened the way to the 1st Division. By 0830, 28 July, the 3rd Battalion, 16th Infantry, had patrols in Sperlinga, and two hours later in Nicosia. Some sniping was encountered as well as

resistance from dug-in emplacements on a few high, rocky points in the north end of town. Before the day was over, the 16th Infantry had captured seven hundred Italians and a few Germans who failed to escape from Nicosia.

For General Guzzoni, the loss of Nicosia was a frustrating development. He had intended to hold Nicosia, which he considered one of the key positions on his main line of resistance. He thought that Hube had the same idea. But during the afternoon of 27 July, Guzzoni had learned from the XII Corps headquarters that Colonel Fullriede had received orders to withdraw.

General Guzzoni’s immediate inquiries produced the information that Hube was beginning the withdrawal to the Etna line. Though the Sixth Army commander did not know it, Hube’s chief of staff on 26 July had attended a meeting at Kesselring’s headquarters and had returned the same day to Sicily with verbal authorization to start consolidating the German forces on the island for immediate evacuation. Hitler’s reaction to Mussolini’s dismissal was taking effect. Early on 27 July, therefore, Hube had instructed Rodt to reconnoiter suitable defensive positions just forward of the Etna line for the withdrawal of Group Fullriede that night.

At Guzzoni’s request late in the afternoon of 27 July, Hube promised to amend his orders to Group Fullriede. The German battle group would stop its withdrawal and would organize a new line running along the Nicosia–Agira road, thus closing the gap which had existed between Rodt’s two battle groups. Guzzoni then promised that the remnants of the Aosta Division would hold the 3,000-foot-high mountain pass (Colle del Contrasto) on Highway 117 about halfway between Nicosia and Mistretta. By consolidating the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division and holding the pass, the Axis could stop an American thrust north along Highway 117 and thus protect the interior flanks of the 29th Panzer Grenadier and Assietta Division deployed along the north coast. Guzzoni was also worried that an American breakthrough at the pass would unhinge from the north coast the entire main line of resistance, a move that would seriously endanger all of the Axis units to the south.

Apparently neither Rodt nor Fullriede received word of Hube’s promise to delay Group Fullriede’s withdrawal from Nicosia, for without informing the Aosta Division, Fullriede began withdrawing his battle group that night to the new positions he and General Rodt had previously reconnoitered: six miles east of Nicosia extending from Gagliano (just north of Agira), through Serradifalco and Cerami (both on Highway 120), to Capizzi (some three miles north of Cerami). The Aosta Division hastily joined the German withdrawal. The result was that some units became lost in the mountainous terrain while others, apparently not receiving the withdrawal order, stayed to fend off the American thrust on Nicosia the following day. At the important mountain pass on Highway 117, a battalion of the Aosta Division pulled back to join the general rearward movement, and, as a consequence, opened the north coast road to American advance.25

Coast road patrol passing the bombed-out Castelbuono railroad station, 24 July

Along the North Coast

Despite mine fields and blown bridges, the 45th Division had advanced rapidly during the night of 23 July and the following day. The newly committed Group Ulich of the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division was not strong enough to contest seriously the American advance. By blowing the bridge over the Malpertugio River, five miles east of Cefalù, and by liberally planting mines in the river bed, Group Ulich brought the 157th Infantry to a temporary halt. The 179th Infantry, which had been following a secondary road six miles inland, reached the town of Castelbuono, eight miles north of Petralia. This brought the 45th Division on line with the 1st Division.

When General Bradley directed General Middleton to keep the pressure on along the north coast road, Middleton sent the 180th Infantry through the 157th on the evening of 24 July. The 180th Infantry crossed the Malpertugio River during the night, and under almost constant artillery, mortar, and machine gun fire, on the following day uncovered a new German line on the high ground just forward of the Pollina River, where the Germans occupied an extremely strong, natural defensive position hinged on the 3,000-foot-high Pizzo Spina. The coastal highway skirts the base of almost vertical cliffs leading

to the crest of the heights. With their main battle position on the west side of the river, the Germans did not demolish the highway bridge, but deployed their infantrymen and supporting weapons on the ground controlling the coastal highway. The first American task was seizure of Pizzo Spina, and Colonel Cochrane, the 2nd Battalion commander, hoping to nutcracker the Germans, sent Company F to occupy a defended blockhouse at a bend in the highway just under the enemy guns on Pizzo Spina, and Company E inland up a ravine to come in on the left of the German line.

While Company E made its tortuous way through the ravine toward the southern slopes of Pizzo Spina, Company F, under heavy German artillery and small arms fire, took, but soon gave up, the blockhouse and withdrew.

Cochrane immediately sent in Company G, which, with the reorganized Company F, tried a frontal attack against the German positions. Scaling the almost vertical cliffs, with friendly artillery bursting fifty to seventy yards ahead of the skirmish line, using rifle fire, rifle grenades, and 60-mm. mortars to aid their advance, the two companies climbed from sea level to almost 3,000 feet in less than a thousand yards. But it was slow going. The advance brought down damaging barrages from enemy artillery and heavy weapons, and German infantrymen rolled hand grenades down the slopes. The supporting 4.2-inch mortars, from positions 500 yards behind the line of departure, blanketed observed and suspected targets, and with white phosphorus shells neutralized some enemy positions high among the crags.

Just as the advance seemed about to stop, Company E bounded in on the German left and overran that end of the enemy line, gaining positions near the pinnacle of Pizzo Spina. Able to enfilade the rest of the German line, the company drove the Germans down the eastern slopes. Company F moved up to the pinnacle, while Company G dropped off the slopes to occupy the blockhouse position on the highway.

Group Ulich was not yet ready to give up its Pollina River line. Shortly after the Americans occupied Pizzo Spina, the Germans launched the first of three counterattacks against the mountain pinnacle. German direct artillery fire from across the river at ranges of less than 3,000 yards was precise in searching out American positions. But observation posts on Pizzo Spina enabled American artillery observers to bring down heavy fire on the counterattacking forces. Along the coastal highway, a platoon of 4.2-inch mortars stopped one German thrust by laying down a 100-round, thirty-minute, mixed white phosphorus and high explosive concentration. Though some small units gave way slightly, and though the line close to the shore surged back and forth for a depth of three hundred yards, the Americans held. After one last try just before darkness, the Germans pulled back across the river, with American artillery fire so heavy and accurate that the Germans could not demolish the bridge.26

The 180th Infantry could not seize the opportunity to pursue. Fourteen unidentified naval vessels, four of which were believed to be cruisers, were sighted off

Campofelice, between Cefalù and Termini Imerese. Fearing that these were Axis ships, General Bradley halted the 45th Division advance and instructed General Middleton to prepare to defend the coast line against a possible Axis amphibious landing. The 180th Infantry consequently faced toward the sea near Pizzo Spina, while the 157th Infantry, with tanks from the 753rd Medium Tank Battalion, deployed along the beaches in the rear. Not until early the next afternoon, 26 July, did a division artillery liaison plane identify the vessels as American destroyers and mine sweepers.27

Oddly enough, General Hube feared that these vessels were part of an Allied amphibious force moving to a landing in the rear of the Santo Stefano line, the northern hinge of the main line of resistance. He, therefore, alerted Axis units all the way to Calabria to be ready to repel a landing.28

Group Ulich, meanwhile, had moved to a new line closer to Santo Stefano di Camastra, a line which ran from Castel di Tusa (on the coast) south through Pettineo to Castel di Lucio, the northern half resting behind the Tusa River. Late in the afternoon of 26 July, the 2nd Battalion, 180th Infantry, reached the Tusa River, halted in the face of heavy German small arms and artillery fire, and found the Germans in a strong, natural defensive position on a very steep hill forming the eastern slope of the Tusa River valley. Here, too, the Germans had not demolished the highway bridge.

While the 2nd Battalion made a show of crossing the river near the bridge, the 3rd Battalion, 180th Infantry, swung inland to outflank the German position. At 2030, the battalion seized a high hill overlooking the village of Tusa, two miles inland from the coast, west of the Tusa River and at the end of a fishhook road. Across the river, on a high ridge at another road end, lay the village of Pettineo. Since the Tusa and Pettineo ridges formed the key to a successful Tusa River crossing, the 3rd Battalion’s mission was to get up on the Pettineo ridge, from where it could then drive north and strike the main German position near the coast on the flank and in the rear.

Early on the morning of 27 July, the 3rd Battalion made its move. Tusa fell at 0600; there was little opposition. But nine hours later, the 3rd Battalion had managed to progress only a few hundred yards more, up to the curve of the fishhook road overlooking the river. Cognizant of the threat that this movement presented to his main battle position, Col. Max Ulich had a reinforced infantry battalion well dug in on the Pettineo ridge to block the 3rd Battalion.

The inability of the 3rd Battalion to get across the Tusa River and outflank the main German line threw the entire weight of the attack on the 1st Battalion, 180th Infantry, which tried to cross the river near the coast. One company managed to get across the bridge just after noon, but artillery fire had so damaged the bridge structure that it collapsed shortly thereafter.

This, coupled with heavy enemy fire, prevented the battalion from reinforcing the one company on the east bank of the river. Though it managed to hold on to a precarious position for the rest of the afternoon, just after dark the battalion commander pulled the company back to the west side of the river.

It was on the same evening, thirty miles inland, that the Germans had given up Nicosia. Though Guzzoni might disagree with Hube on some matters, he was in basic agreement with the German commander that the Axis front as it was then constituted could not long be held with the forces available on the island. The eastern third of the front, manned by the reinforced Hermann Göring Division, appeared to be relatively strong and could be expected to hold. But the pressure being exerted by the Americans and the Canadians against the northern and central sectors seemed to demand a consolidation of the Axis forces on the shorter front of the Etna line. The German withdrawal from Nicosia was the beginning of this consolidation. On the next day, 28 July, as the 1st Division entered Nicosia, Group Ens gave up Agira to the 1st Canadian Division and pulled back toward Gagliano to join forces with Group Fullriede. The Hermann Göring Division extended its eastern flank to block a further Canadian advance, while the entire 15th Panzer Grenadier Division prepared to block a push eastward by the 1st Division. Thus, on 28 July, the central sector of the Axis front had consolidated near the Etna line. To cover this pullback, and to delay the Americans on the north coast as long as possible, General Hube ordered the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division to hold forward of Santo Stefano di Camastra at least through the night of 30 July before moving back on line with the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division.

In the meantime, plans for a combined Anglo-American August offensive had solidified. On 25 July, General Alexander had met with his two army commanders at Cassibile, the new 15th Army Group command post south of Syracuse. Here the plan for the expulsion of the Axis forces from the Messina peninsula was agreed on and placed in effect. The Seventh Army was to continue eastward along the two axes previously assigned in “a sustained relentless drive until the enemy is decisively defeated.”29 General Bradley’s II Corps would continue to control the ground operations along both axes.30

The Eighth Army was to make its major effort on the left with the British 78th Division thrusting to the north along the Catenanuova–Centuripe–Adrano axis and the 1st Canadian Division driving to the east along Highway 121 through Regalbuto. On the Eighth Army’s right, the 13 Corps was to feint an attack toward Catania to deceive the Germans into thinking this was the main British effort. After the fall of Adrano, which General Montgomery estimated to be the key to the main Axis Etna positions, he expected the Germans to pull out of Catania. Then the 13 Corps would exploit to Messina around the eastern side of Mount Etna.31

General Bradley, in accordance with the new directive to push on to the east—although his push had never really stopped—decided to relieve the 45th Division

with the 3rd Division on 31 July and to pass the 9th Division through the 1st Division. But assembling the bulk of the 9th Division would take time, and Bradley directed General Allen to keep the 1st Division moving toward Cerami and Troina until the 9th Division could effect relief.32

The American and British foot soldiers would have plenty of help in this final push to evict the Axis forces from Sicily. The Allied air forces roamed almost at will through the skies above the battlefield. Almost no hostile aircraft rose to contest Allied air superiority. By the time Palermo fell, no Axis aircraft were operating from Sicilian airfields; all had been withdrawn to the Italian mainland or destroyed. With the enemy’s air out of the way, the attention of the Allied air commands could turn to rendering direct and close support to the foot soldiers.

The Seventh Army’s advance on Palermo had been so swift that it had been unnecessary to call in many close support air missions, with the result that most tactical sorties had been flown well ahead of the advancing units in strafing and bombing attacks against targets of opportunity and the road networks leading to the active front. Group Ulich had suffered heavily from just such attacks, losing fifty vehicles and a complete artillery battery while on the way to oppose the 45th Division’s advance along the north coast road.33

By this time, too, Allied fighters, fighter-bombers, and light bombers operated from captured airfields on Sicily—at Licata, Ponte Olivo, Comiso, and others. Both the U.S. 31st and 33rd Fighter Wings flew under XII ASC control. By 30 July, all units of the U.S. 64th Fighter Wing had moved to Sicily. Ample air support would be available to support the final drive.34

Naval support was also available, if not in the quantity that had been available on 10 July. On 27 July, when Palermo was first opened to Allied shipping, Admiral Hewitt created Naval Task Force 88, consisting of the last few remaining American warships in Sicilian waters. Under the command of Rear Adm. Lyal A. Davidson, NTF 88 became “General Patton’s Navy”—set up to support the Seventh Army’s operations along the north coast.35 To carry out this mission, Admiral Davidson was initially assigned 2 cruisers, 14 destroyers, 14 MTB’s, 19 landing craft (2 LSTs, 10 LCI(L)’s, 7 LCTs), and a number of small escort craft.36 On the east coast, Admiral Cunningham had warships available to support the Eighth Army operations, and was prepared to furnish a number of landing craft to lift British ground units around the stubborn German Catania defense line. Rear Adm. R. R. McGrigor, the senior British naval officer in Sicily, had completed all preparations necessary to launch an amphibious end run.37

Even as the 3rd Division began its move forward to effect the relief of the 45th Division on the north coast road, General Middleton on the morning of 28 July leapfrogged regiments, ordering the 157th Infantry forward to take up the fight. Colonel Ankcorn’s leading battalions failed

to get off to a fast start, for a blown section of the coastal road west of the Pollina River delayed their arrival at the Tusa River until late in the afternoon. Eventually, at 1745, the 1st Battalion, 157th Infantry, relieved the 180th Infantry Battalion at the river. Immediately, Colonel Murphy, the battalion commander, sent Company B across the river to the left of the demolished bridge and along the flat coastal strip. Though it suffered some casualties from mines and from enemy artillery fire, Company B started working up the slopes of the Tusa ridge—Hill 335—across the top of which the 3rd Battalion, 15th Panzer Grenadier Regiment had dug in. In the meantime, Company C crossed the river to the right of the demolished bridge and started up the forward slopes of the hill, finally reaching a terrace just under the steep crest where heavy small arms and mortar fire forced a halt. Company A, put in on the right of Company C, could make no more progress. As night came, both companies clung precariously to their terrace perch. But by this time, Company B had succeeded in reaching the top of the ridge overlooking the sea. The company was low on ammunition, but it formed a line near the edge of a clearing, and, though harassed throughout the night by sniper fire and hand grenades, it held.

While the 1st Battalion developed the Tusa ridge positions, the 2nd Battalion, 157th Infantry, had swung inland, passed through the 3rd Battalion, 180th Infantry, at Tusa, and crossed the river into Pettineo by darkness of 23 July. In contrast to the tough resistance encountered by the 180th Infantry the previous day, the only opposition to the advance on the 28th came in the form of a small counterattack launched by a portion of the 2nd Battalion, 15th Panzer Grenadier Regiment. Thereafter, the Germans pulled back to the high ground along the Motta d’Affermo–Mistretta road. The same day, to the south, the 18th RCT began sending patrols north on Highway 117 toward Mistretta, thereby threatening the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division’s open left flank.

On the morning of 29 July, the 2nd Battalion pushed out toward Motta, driving for two hills south of town. This day, though, the enemy refused to relinquish ground, and the battalion’s attempt to flank the German line to the north was of no avail. To add weight to the turning movement, Colonel Ankcorn, the 157th Infantry Combat Team commander, committed the 3rd Battalion, which crossed the Tusa River behind the 1st Battalion, moved south toward Pettineo, then turned inland to drive directly on Motta. Covered by a three-battalion artillery concentration (almost 1,500 rounds) which forced the two forward companies from the 1st Battalion to cling to their terrace walls while shells exploded almost in their faces, the 3rd Battalion moved slowly toward Motta. The advance was still uphill, for Motta itself was some 900 feet higher than the Tusa ridge line and represented the key terrain before Santo Stefano, the 45th Division’s objective. This ground the 45th Division would remember as “Bloody Ridge.” By 1900, somewhat disorganized, the two 157th Infantry battalions halted for the night short of Motta.

The 29th Panzer Grenadier Division was still not ready to give up this line before 30 July. Though General Fries had lost the Tusa River line and faced the threat of an envelopment of Santo Stefano from the south—Mistretta (ten miles to the south) was entered by American

Demolished bridge along highway 117 between Santo Stefano and Mistretta slows down 45th Division troops

troops on 29 July—he ordered Colonel Ulich to mount a counterattack on the morning of 30 July to retake the Tusa ridge to slow the American advance toward Santo Stefano from the west. General Fries was confident that the rough nature of the terrain between Mistretta and Santo Stefano, coupled with the ease with which Highway 117 could be blocked at almost any point, precluded any rapid American advance from the south. The most serious threat to Santo Stefano remained the 45th Division; this was the unit that had to be halted if Santo Stefano was to hold out another twenty-four hours. To make the counterattack, General Fries attached to Group Ulich a battalion from the 71st Panzer Grenadier Regiment and two battalions from the division’s artillery.

At 0430, 30 July, without preparatory artillery fires, the German attack jumped off from just north of Motta. Initially, it achieved full surprise and gained some ground, but at heavy cost. The 1st and 3rd Battalions, 157th Infantry, recovered their composure quickly and dug in to hold. Alert to its supporting role, the 45th Division artillery began firing soon after the attack developed. From the south, the 2nd Battalion poured heavy fire on the German flank. By noon, the impetus of the German attack slowed considerably. After taking a fifteen-minute, three-battalion artillery concentration shortly after 1300, the Germans stopped.

That night, the 157th Infantry resumed its advance. Motta fell without a fight. Leaving one reinforced battalion to hold Santo Stefano as long as possible, General Fries moved his division eastward. The town fell the next morning.38

For the 45th Division, Santo Stefano marked the end of active combat operations in Sicily, although the 157th Infantry would take part in an operation near Messina late in the campaign. For a short time, at least, the division could enjoy a respite from the bloody business of war.

In its first twenty-one days of combat in World War II, the 45th Division had earned an enviable reputation. It had marched and fought from Scoglitti to the north coast, suffered 1,156 casualties, and taken 10,977 prisoners.

As the 3rd Division moved into line on the north coast, the 1st Division, on the II Corps southern axis, Highway 120, began what was to be its hardest and bloodiest battle of the Sicilian Campaign—Troina.