Chapter 17: The Battle of Troina

The 1st Division’s pursuit of the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division from Nicosia came to an end on 29 July, when heavy rain and stubborn rear guard resistance stopped the 16th RCT about four miles east of the former Axis stronghold. That afternoon the forward troops of the 16th Infantry dug in on three hills which commanded the highway about three miles short of Cerami. Beyond Cerami, eight more miles of road would have to be taken before the 1st Division could enter Troina.

Meanwhile, General Rodt’s 15th Panzer Grenadier Division had completed its preparations to move back toward the Etna line, which, in the northern sector extended from Sant’Agata to San Fratello and Cesarò, first occupying an intermediate defense line hinged on Troina. Along this forward line, General Rodt disposed Group Fullriede in Troina and along the high ground north of the town, Group Ens in the terrain to the south.1 Rodt’s division, united for the first time during the campaign, maintained a loose contact with the Hermann Göring Division on its left near Regalbuto, and on the right with the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division, also pulling back along the north coast toward the Etna line. The Aosta Division, holding a vague sector between the 15th and 29th Panzer Grenadier Divisions, placed its four artillery battalions under German control just east of Troina.2 As early as 22 July, American intelligence officers were describing the Etna line with accuracy.3 But they guessed that the Germans were building up another, more highly organized, final defensive line from which they could launch a vigorous counterattack as well as screen a possible withdrawal to the Italian mainland.4

In this the Americans guessed wrong. General Hube had no concept of a final defensive line. Rather, he saw in the northeast sector of the island ground on which he could establish a succession of strongpoints—as opposed to a line of defenses—almost, but not quite, as though lateral means of communication did not exist. The fact that the terrain denied freedom of maneuver was something Hube could use to his advantage. If small garrisons proved effective, they could stay as long as they were not endangered by the fall of a flanking stronghold. And when the garrisons were in imminent danger of falling or of being encircled, they would have at their rear a good road along which

they could withdraw. At the same time, most of the defending forces would be well away from the front lines.

It was the failure to appreciate the priority which the Germans gave to their withdrawal movement that caused the Americans most of their trouble at Troina. This failure was spotlighted by the unremitting search for a final defensive line in the Seventh Army’s zone. All information pointed to heavy troop and matériel movements passing through, and not stopping at, Troina. Air reconnaissance also discovered a large bivouac area near Cesarò, and when direct observation from Nicosia and Cerami showed how lightly Troina was held, the guesses about where the Germans would hold focused farther and farther eastward. On 28 July, the II Corps G-2 believed the Germans would continue their rear guard actions and make a final stand either along a line located on high ground some five miles east of Troina, or along a line between Cesarò and Randazzo. The reason: “The successful defense of Catania and the Catania Plain have raised German morale and hopes to the point where they are willing to gamble two or three more divisions to hold a Sicilian bridgehead.”5

On 30 July, the II Corps G-2 said: “Indications from observed bivouac areas north of Cesarò and the general withdrawal of the enemy east of Cesarò following the day’s fighting are that the enemy is falling back to that area.”6

The II Corps and the 1st Division intelligence estimates also emphasized the poor condition and small size of the enemy force holding Troina. Relying chiefly on prisoner of war and civilian testimony, the 1st Division G-2 (Lt. Col. Ray W. Porter, Jr.) reported at 1215, 29 July, “Germans very tired, little ammo, many casualties, morale low.”7 And two days later, he said: “Offering slight resistance to our advancing force, the enemy fought a delaying action while the bulk of the force withdrew toward Cesarò. The delaying forces consisted of small groups of infantry with mortars and machine guns and were supported by artillery.”8 That same evening, 31 July, the II Corps announced: “Indications are Troina lightly held.”9

The terrain facing the II Corps forces on Highway 120 was difficult. Half a dozen ridge systems running generally north and south compartmentalize the terrain between Nicosia and Randazzo, and each series of hills commands the highway. Any of several might have served to anchor a defensive line forward of the Etna positions but the Troina ridge in particular possessed several choice features: avenues of communication in the vicinity of the town were so few and the hill systems so arranged that half a dozen fortified hills could completely control not only Highway 120 but also any endeavor to flank these positions—any attempt to envelop the town would require a very wide encirclement; gun positions in the town not only looked down on the highway, they could also pour effective fire on Cerami (from which an attack had to be launched) and especially on a wide curve which the highway made as it left Cerami; the cup-shaped valley between Cerami and Troina was exceptionally barren and devoid of cover; and, above all, since the Germans had shown from the beginning of the campaign

Troina ridge from the high ground near Cerami. Mount Etna is in the background

Looking west from the town of Troina

that the one line they insisted on holding was the line stretching along the southern base of Mount Etna, Troina was the best place along Highway 120 that would serve as the continuation of the line from Etna to the north coast. Nicosia and even Cerami were not only comparatively easy to outflank, but were also too far from the towns holding out against the Eighth Army—first Agira and Regalbuto, but above all Adrano and Catania. To give up these towns (except on a definite timetable) would mean that the greater part of the German garrison in Sicily would be trapped in the Etna area, the limited communications and stone walls of which had been a major factor in the entire delaying action. Again, to let Troina go and try to use Cesarò, (which had nearly the same bundle of things to recommend it) would bring the Allies entirely too close to the southern portion of the Etna line. Cesarò, had to be given up after, not before, Adrano, to allow the German center to evacuate along two roads to Messina instead of only one. In other words, the loss of Troina would mean that the entire Etna line would become a dangerous liability.

The terrain canalized the 1st Division’s advance, and Troina was an effective blocking point. The road itself came under interdiction possibilities at Cerami. Just south of Cerami, a high hill (Hill

1030), and just beyond that the Cerami River, afforded cover for an assembly area, and a stream-bed approach to the southeast of Troina—the so-called Gagliano salient. These features in the approaches to Troina weakened somewhat the all around defense capabilities.

Unlike most other towns in Sicily, Cerami has wide streets. Through traffic would not be a great problem, and a few blown houses would not become an effective barrier. But as the highway comes in from the southwest, crosses the south end of town, then turns north, the exposed road emerges into point-blank range for any artillery in or south of Troina. Beyond Cerami, the highway bears east for a mile and a half before making a reverse loop which is a pocket. Sheltered from artillery positions on Monte Acuto by Hill 1234 on the north and from Troina by Hills 1140 and 1061 on the east, the road pocket around a small valley head was in complete defilade; high-angle fire alone could reach it. But the mountain streams that run through the pocket make steep gulches, and two blown bridges in the loop would add considerably to the 1st Division’s engineering problems.

Beyond the face of Hill 1030, Troina looks down the throat of any force approaching from the west. Two and a half miles of the road were completely dominated by positions in Troina and on the north extension of the Troina ridge.

Besides controlling the highway, positions in Troina also covered the hill noses west of the town. Any approach to Troina by troops north of the road must come down these noses, and artillery fire from across the small valley between them and Troina could literally slap an advance in the face. The major hill noses are those of Hills 1061 and 1035, which could be fired upon also from Monte Acuto. The south and southwest faces of Hill 1061 were defiladed from fire from Monte Acuto; but Hill 1035 (Monte Basilio), an extension of the Acuto ridge, was vulnerable to enfilade on both faces. Thus, an advance on Troina in the terrain north of the highway would be caught between two fires.

The Monte Acuto position, almost a mile high, marked one of the strong features of the German line. It dominated the lower ridges and ridge noses toward Troina. It covered the valley and the entire Troina front; the highway for some distance west of Troina, and east of the town as far as the Troina River crossing; the front of the positions south of Troina along the Gagliano road; and its own approaches: west from Capizzi, and southwest around the flank of Hill 1254 towards Cerami. Only from the north, where the ground ascended to Monte Pelato, was the Monte Acuto position vulnerable, but only if the defenders could not hold the higher points.

Troina proper, a town of 12,000 people, was itself a natural strongpoint, built on a bluff ridge, high and dominating. The highway did not go through the town; rather, it ran along the town’s front, then turned left and crossed the ridge through a sort of pass. This had several significant implications. First, Troina was not in itself a roadblock, but its high fortified position enabled it to control not only Highway 120, but also the road southeast to Adrano and a secondary road running southwest to Gagliano. Second, the highway swung around behind the ridge and was defiladed for some distance northeast toward Cesarò. This would make use of the highway possible even under attack from the west, and

make it available for a withdrawal from Troina should the situation become untenable. These advantages did not obtain against positions on the Troina ridge at Monte Basilio (Hill 1035) which, if taken, would threaten to cut off any forces in Troina from withdrawal to the east.

Troina’s streets were narrow with right angle turns. The main street made such a turn on the northeast face of a cliff. At the top of the town, two spires of a Norman church overlooked a small public square. At the cliff front a round feudal tower provided an ideal observation post. The streets, buildings, and massive stone houses made good holding places for infantry. Once beaten down from the front, the infantry could always crawl out the back way and down the road to Cesarò.

The Troina ridge extended northeast beyond the town, covered the Cesarò, road, and afforded excellent artillery emplacements. Shielding the town on the west was another ridge system, with key strongpoints both north and south of the highway, and there would occur some of the bitterest fighting in the battle for Troina, particularly at three key points: Hill 1061, north of the highway; Hills 1006 and 1034, south of the road. Below Hill 1034 the same ridge turned to the east, so that south of Troina the town’s defenses were at right angles to the positions north and west of the town. The south face held the key strongpoints of Hill 851, Monte Bianco, and Monte San Gregorio. Farther south lay the Gagliano salient: Gagliano, Monte Pellegrino, and Monte Salici, the latter two lying on high ground extending east across the Troina River. Gagliano was accessible by road from the south; it had few natural defenses and was too far from Troina to be held by a large force. An attacker could make use of the lower half of the Gagliano–Troina road to help gain flanking approaches to the other two hills in the salient and to the key points on the ridge line south of Troina. A powerful strike here could crack the salient and turn up both flanks, or else force a rapid withdrawal from the Pellegrino positions north to the ridge. This would pose a serious threat to the left flank of the Troina positions, and like Monte Basilio north of the town, the occupation of Monte Pellegrino would put the attackers in position seriously to threaten the highway east of Troina, the only good route of withdrawal.

Throughout the Troina area, the ground was rugged. Hill slopes rose abruptly, forming canyons rather than valleys, and usually separated by rocky streams only a few feet wide. The Americans would find these streams sown with mines. Soldiers would have to scramble over surfaces that would tax the agility of a mountain goat. They would find objectives as difficult to recognize as to reach, for the hills looked much alike, and a distinguishing feature noted from one angle would tend to disappear when viewed from a different angle. The Troina area was a demolition engineer’s dream. The smallest ravine was a deep gulch, and a destroyed road would require a bypass down a long descent. The terrain favored the first comer, especially the defender, and the Germans proved to be most adept in selecting and employing the terrain for defense.

1st Division patrols, from both the 16th and 18th RCT’s, on 30 July had already probed the approaches to Cerami. Noting some artillery and much activity in the town, they made no attempt to enter it. A 39th Infantry attack was scheduled for the following day. This

4th Tabor of Goums moving north of Highway 120 toward Capizzi, 30 July

unit, now under Col. H. A. Flint, had been attached to the 1st Division pending the arrival of the remainder of the 9th Division.

North of Highway 120 the 4th Tabor of Goums, attached to the 18th Infantry, moved toward Capizzi on 30 July without incident until late in the day. Then small arms and mortar fire stopped the goums. Not until daylight, 31 July, and only after a heavy volume of covering artillery fire were the Goumiers able to enter Capizzi. An advance that afternoon of a mile and a half northeast of Capizzi to Hill 1321 (Monte Scimone) stirred up only minor resistance. The Italian troops from the Aosta Division were falling back and in the process, though unknown to the Americans or Goumiers, were strengthening the right flank of the German defenses at Troina.10

South of the highway similar incidents occurred. A troop from the 91st Reconnaissance Squadron occupied Monte Femmina Morta (less than 1500 yards west of the German ridge positions—Hills 1006 and 1034—west of Troina) on 30 July and gained contact with 16th Infantry patrols. Another troop of the reconnaissance squadron, furnishing right flank protection for the division, made

contact with the Canadians in Agira, then moved northeast along the unimproved road toward Gagliano. Late in the afternoon, a huge crater just short of the village halted further progress. The enemy was nowhere in evidence.

Not until the following morning, 31 July, when the reconnaissance troop tried to repair the crater south of Gagliano did a detachment of the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division put in an appearance and contest the road. And not until the next day, 1 August, after heavy supporting fires were laid on the enemy, did the reconnaissance troop enter Gagliano.11

Meanwhile, Colonel Flint’s 39th Infantry on 30 July had passed through units of both the 16th and 18th Regiments immediately north and south of the highway and by evening was prepared to jump off at dawn to take Cerami, then continue to Troina. Both objectives seemed ready to fall, for prisoners’ statements that day underscored the weakness of Troina’s defenders. Air reconnaissance confirmed this impression, for pilots could find little evidence of strong defenses around the town. Only light traffic passed between Troina and Randazzo. Troina seemed to be just another place with a skeleton garrison to fight a brief delaying action before pulling out, even though one report indicated that “they seem to be right in there.”12 Consequently, General Allen late on the evening of 30 July planned to reinforce the 39th Infantry’s attack by committing the 26th Infantry through the 16th south of the highway at darkness on 31 July for a direct thrust to Troina by daylight of 1 August.13 This, Allen hoped, would coincide with the 39th Infantry’s advance eastward from Cerami toward the northern edge of Troina.

In support of the attack, General Andrus, the 1st Division’s artillery commander, deployed an impressive array of supporting fires. Controlling the eight organic battalions of the 1st and 9th Divisions, plus almost the same number of artillery battalions attached from the II Corps, General Andrus had at his disposal 165 artillery pieces.14

This massive artillery support actually did not appear to be needed, for when Flint’s 39th Infantry jumped off toward Cerami at dawn on 31 July the troops met no opposition except that offered by the rough terrain north of the highway. By 0900 that morning a battalion was in Cerami.

Though Allen had contemplated moving Bowen’s 26th Infantry through the 16th Infantry for a direct thrust to Troina, Flint’s easy success made commitment of the 26th seem unnecessary. Allen therefore instructed Flint to continue alone, his mission to capture Troina and the high ground east of Troina astride Highway 120.15

Optimism was the order of the day when Generals Bradley and Allen visited Flint’s command post early in the afternoon. They passed along a report from civilians who said the town contained only a few troops, some antitank guns, an antiaircraft battery, and one heavy gun.

Forward Observation Post near Cerami. Artillery fire is being directed on Troina, in the distance

Artillery in position near Cerami. The 155-mm. rifle is firing on Troina

They informed Flint that they had no specific deadline for his capture of Troina. They also suggested he use a trail along an aqueduct for his approach to the town while artillery worked over the reverse slopes of the hills shielding Troina.16

Despite this optimism Flint’s troops were already running into trouble. German mortar and artillery fire denied the Americans a direct approach to Troina. Covered by heavy concentrations of supporting artillery, the regiment advanced only with difficulty. By the end of the day one battalion had reached Monte Timponivoli (Hill 1209), about halfway to the objective north of the highway, and two hills south of the road on line with Monte Femmina Morta.

Yet American optimism persisted. German prisoners emphasized “There is a pull-out now. Troina has a couple of guns in it.”17 General Allen still felt the 39th Infantry could take Troina alone, but he again turned to the idea of bringing up the 26th Infantry if it became necessary in the next few days.18

For Flint’s second day of attack on Troina, 1 August, the Tabor of Goums, released from attachment to the 18th Infantry and placed under division control, was to cover the 39th’s left flank by moving eastward toward Monte Acuto, then southeast to Monte Basilio, and eventually past Troina and the highway east of town. Flint’s scheme of maneuver envisioned Lt. Col. Van H. Bond’s 3rd Battalion making the main effort by following the general line of the highway to seize high ground adjacent to and north of the town. The other two battalions were to be echeloned to the rear on both flanks, the one on the right operating as far as two miles south of the highway.

Though the plan for the ground assault seemed to promise success, the artillery was unable to give the expected support because all the battalions could not be brought far enough forward in time for the attack. The road was in poor shape and clogged with traffic. The Luftwaffe (making one of its rare appearances) had strafed and bombed artillery positions and caused some confusion if not casualties. And German artillery was interdicting the routes of displacement.19

Despite the absence of what was considered adequate artillery support, Flint decided to go ahead. Perhaps he had little choice in the matter. The remainder of the 9th Division was scheduled to unload in Palermo on 1 August and General Allen felt a moral obligation to capture Troina before turning over “a tight sector” to General Eddy.20 In any event almost everybody expected Troina to fall easily.

When Colonel Bond’s 3rd Battalion, 39th Infantry, jumped off at 0500, 1 August the regiment was already halfway from Cerami to Troina: a scant four miles from the objective. Advancing southeast from Monte Timponivoli (Hill 1209)

39th Infantry half-track squeezing through a narrow street in Cerami

north of Highway 120, Bond hoped to move as rapidly as the terrain permitted. He would have to cross a series of abrupt hills that paralleled the highway, but these constituted no ridge line in the real sense of the term. The 3rd Battalion, though, would be advancing along hill noses west of Troina, noses covered by fire from Troina as well as from Monte Acuto. Colonel Bond was to be disappointed. His battalion immediately encountered mortar and small arms fire, and beyond one thousand yards from Monte Timponivoli the battalion could not advance. Artillery fire against suspected enemy positions having no effect on the intensity of the German reaction, Bond in mid-morning pulled back to his line of departure. (Map 5)

The withdrawal was fortunate. As a result, Bond was ready to meet and repel a relatively small German counterattack down the aqueduct trail from the north. With effective artillery support, Bond’s 3rd Battalion turned back the threat before noon. Yet continued mortar and machine gun fire from German positions east and north of Monte Timponivoli was in sufficient volume to negate hopes for any advance at all toward Troina.

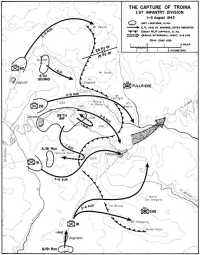

Map 5: The Capture of Troina, 1st Infantry Division, 1–6 August 1943

Pessimism might have been warranted had not Group Ens’ defenses south of the highway proved porous indeed compared to the defense put up thus far by Group Fullriede north of the road. Maj. Philip C. Tinley’s 1st Battalion, 39th Infantry, had its leading company three miles ahead of its line of departure and ensconced on Hill 1034, a key spot on the important ridge position west of Troina, about the time that Bond was repelling the counterattack to the north. Because the company had met no opposition, Tinley reinforced it early in the afternoon with another rifle company. As the lead company dug in on Hill 1034, the company coming up behind rounded up thirty prisoners and entered the perimeter. Either the 1st Battalion had moved too rapidly or Group Ens did not yet have its defenses well organized. In any event, Colonel Ens began to prepare to retake the high ground, less than a mile west of Troina, and dislodge the Americans, who had a clear view not only of the streets of Troina but of artillery positions farther to the east.

The contrasting fortunes of the battalions north and south of Highway 120 gave General Allen no sure guidance on whether or not to commit the 26th Infantry to reinforce the 39th Infantry’s attack. He first decided to act on the side of prudence and in mid-morning ordered Colonel Bowen to pass his 26th Infantry around Flint’s forces, to the north of the highway, instead of on the south side as originally planned. Operating north of the 39th Infantry positions, Colonel Bowen was to cut the highway about two miles beyond Troina by striking eastward, first to Monte Basilio, and then to a hill mass commanding the road. Now, too, the 16th Infantry was also to join the fight. Allen directed Colonel Taylor to attack on the 39th Infantry right, striking out from Monte Femmina Morta toward the south side of Troina and then on to Hill 1056, south of the highway and about a mile east of the town. By gaining Hill 1056, the 16th Infantry would cut the road leading from Troina to Adrano, one of the two exit roads from Troina available to the Germans. In effect, Allen was applying the same tactics used at Sperlinga and Nicosia the week before: a double envelopment of a strong, natural defensive position. General Andrus promised full support for the attack, scheduled to go off at 0500 on 2 August.21

Later, however as word of Tinley’s encouraging progress south of the highway came into division headquarters, Allen began to reconsider. After Flint insisted that his 39th Infantry could do the job alone, Allen definitely made up his mind to let Flint have another try at Troina. Adding support to this decision was a conversation Allen had with General Bradley. The II Corps commander expected the 9th Division to relieve the 1st, not on 4 August as originally anticipated but a day or two later. Since the 39th Infantry seemed to be moving, Bradley agreed that there was no reason for concern over the possibility that the arrival of Eddy’s troops might interfere with Allen’s attack—Troina would surely be taken in ample time to allow the 1st Division to retire to Nicosia and cede the field of battle to the 9th.22

But an hour later, near 1400, Allen again changed his mind. Now, though Flint’s regiment was to continue making the division’s main effort against Troina,

the 26th Infantry was to come up on Flint’s left to go for the hill mass which commanded the highway east of Troina. Taylor’s 16th Infantry was not to be used on Flint’s right, for it appeared that Tinley’s 1st Battalion, 39th Infantry, would be able to take the objective earlier contemplated for Taylor.

As for Bowen, since Allen did not specify the strength Bowen was to employ, the 26th Infantry commander proposed to use two battalions on Flint’s left, as Allen had suggested earlier in the morning. The 1st Division G-3, Lt. Col. Frederick W. Gibb, thought one battalion would be enough, since the Tabor of Goums would be operating on Bowen’s left. Bowen finally decided to jump off in a column of battalions. To satisfy his request for all possible artillery assistance, General Allen gave him four batteries of 155-mm. guns (Long Toms), four battalions of light artillery, and one medium battalion for direct support.23 Despite this help, Colonel Bowen was still worried over the scale of German resistance around Troina: “I think there is a hell of a lot of stuff there up near our objective,” he said, “and down south also.” All the information at Bowen’s disposal pointed toward “a very strong defense,” and he questioned whether “we have strength enough to do the job.” Later, when the 2nd Battalion, 26th Infantry, was moving toward its line of departure, Bowen thought it was “moving right into the teeth of the enemy and not around him.”24

The 4th Tabor of Goums would have been in agreement with Colonel Bowen’s estimate, for the Goumiers that day, trying to push from Monte Scimone to Monte Acuto, had advanced only a mile to the Troina River before being stopped by showers of mortar and artillery fire. Efforts to advance during the night and on the following day, 2 August, met with no success.25

Meanwhile, Flint, on the afternoon of 1 August and with General Allen’s permission, had been trying to take Troina alone. He ordered the 2nd and 3rd Battalions to launch a coordinated attack to the high ground north of Troina. But the push turned out to be a gentle shove that got nowhere. Enemy shelling was the obstacle. Adding to Flint’s problems was a counterattack at nightfall directed by Group Ens against Tinley’s 1st Battalion on Hill 1034, just west of Troina. The Germans “thumped hell out of A and C Companies.” Strong German artillery and mortar fire accompanied the thrust by some two hundred men, which scattered the American companies badly. Hoping to use his reserve company positions—more than a mile to the rear—as a rallying point, Tinley asked permission to withdraw. Flint grudgingly assented. By midnight, Tinley had the battalion well in hand, though Company A had only two platoons left, Company C slightly less. The entire battalion numbered about 300 men, and the Germans were less than 2,000 yards from the 1st Battalion’s positions. Ens had gained his objective, the important ridge line strongpoint at Hill 1034, but instead of exploiting this success, he set his troops to digging in along the ridge to block further

American attempts against Troina he expected from the west and south.26

The third day of the action against Troina on 2 August again proved fruitless. The Goumiers on the division’s left could not cross the Troina River and remained in place throughout the day. Flint’s 39th Infantry was able to do no more, every attempt to advance meeting scorching enemy fires. Only in the terrain between the Goumiers and the 39th Infantry, where the 26th Infantry entered the battle, did the 1st Division achieve any success, and this gain, a result of cautious advance, was only tentative in nature.

Jumping off at 0500 that morning in a column of battalions, the 26th Infantry moved eastward slowly, hampered by the lack of success of the units on its flanks as well as by unsatisfactory communication with them. The leading battalion met little ground opposition, and though they received increasingly heavy enemy artillery fire as well as occasional small arms fire, the forward elements pushed ahead more than a half a mile to Rocca di Mania. With the regiment’s flanks already exposed, further advance seemed not only risky but pointless. Bowen halted his troops and awaited the following day and the execution of a stronger attack which General Allen was even then planning and preparing.

By this time, Allen was finally convinced that he had to make a large-scale and coordinated effort to smash the Troina defenses. His new plan involved employing additional forces in a frontal assault which he hoped would develop in its later stages into a double envelopment.27 He attached a battalion of the 18th Infantry to the 16th on the division’s right for an attack from Gagliano to Monte Bianco, about two miles south of Troina, a key strongpoint on the German ridge defense line. The organic infantry battalions of the 16th Infantry were to take the town and cut the road to Adrano. The 39th Infantry was to seize Monte San Silvestro, two miles northwest of Troina and then go into division reserve. The 26th Infantry was to continue its encircling movement of Troina, swinging past the 39th Infantry to take Monte Basilio and then moving southeast to cut the highway behind Troina.

Though the main attack was scheduled to start at 0300, 3 August, the 2nd Battalion, 16th Infantry, moved out shortly after midnight, leading the regiment in its swing to the south toward the southern corner of the German ridge positions, where the ridge line swings in its arc to the east. The 3rd Battalion followed. By dawn, the leading elements of the battalions were halfway up the slopes of the ridge, ready for the final assault. But as daylight came, German small arms and machine gun fire interfered. The men were pinned to the ground. Several attempts to get the assault moving failed, and by noon it was evident that the 16th Infantry could not move.

Having reached that conclusion shortly before noon, General Allen ordered the battalion of the 18th Infantry attached to the 16th to push beyond its originally assigned objective and take high ground a half mile south of Troina. The 1st Battalion, 16th Infantry, was to assist.

The battalion from the 18th Infantry had been advancing from Gagliano without opposition, though hindered by terrain. General Allen wanted the battalion to speed up its movement, for the two battalions of the 16th Infantry, pinned down on the ridge slope, appeared to be in a precarious position. What Allen wanted to do was divert German attention from the main body of the regiment.28

Before the battalions coming up from the south could start a real push, Group Ens mounted a counterattack around noon, using infantry and tanks in an attempt to throw the advance troops of the 16th Infantry off the slopes of the ridge. Responding to a request from Colonel Taylor, General Andrus put the fire of six battalions of artillery along the high ground. This, plus dogged fighting by the infantry, prevented the men from being overrun.

Although stalled in this counterattack, Colonel Ens kept exerting pressure throughout the afternoon. The strongest effort occurred around 1500, when two hundred men came into such close contact with the American troops that artillery support could not be used. By the end of the day, Companies E and F, 16th Infantry, seemed to have little more than one platoon each remaining, with the others missing. Though the 3rd Battalion, 16th Infantry, was in better shape, it was in no condition to resume the attack.29

Nor could the two battalions on the south make much progress in driving toward Troina from Gagliano. German raids on both flanks and effective fire stopped the push about halfway to Troina.30

Still hoping to keep the attack going on his right (south) flank, General Allen ordered one of the two battalions to make a wider swing to the east and attempt to outflank Troina completely. But a few minutes later, the assistant division commander, General Roosevelt, arrived in the area, took one look at the terrain to the east, and advised Allen against the move. The terrain, much of it sheer rock, and the condition of the units—badly scattered in the process of getting this far—seemed to rule out success.31

Conditions north of the highway were hardly better. A battalion of the 26th Infantry reached its initial objective, Monte Basilio, with surprising ease, about the same time that a battalion of the 39th Infantry had, with the same facility, reached Monte San Silvestro. Yet soon after the leading troops of both regiments reached these hill masses, enemy artillery began to pound them. Observing that the fire was coming from reverse slope positions to the north and east, positions difficult to reach with artillery, Bowen called for an air strike. Some half a dozen Spitfires responded about 1100 and bombed and strafed the north slopes of Monte Castagna and Monte Acuto. The enemy shelling lessened as a result.32

About the time that Bowen was getting his air strike, Flint called for another. He had learned that a road, not shown on available maps, ran generally east and northeast from Capizzi for some fifteen miles to link Monte Acuto, Monte Pelato,

and Monte Camolato. Guessing that the Germans had concentrated their artillery along this road, Flint requested help from the air. Unfortunately, part of Bowen’s forward units and the Goumiers were so close to the road that division headquarters disapproved the request.33

Part of the caution at division headquarters developed after the Spitfires which had responded to Bowen’s call inadvertently strafed the Goumiers, though no serious harm had been done. The Goumiers were still immobilized at the Troina River under the shadow of Monte Acuto, still trying to get across the river and up on the high ground, still incurring heavy casualties in the process.

Communication with the 4th Tabor was rarely as good as with American subordinate units, and for seven hours that day the division headquarters had no word from the Moroccans and consequently no clear knowledge of their location. This did not prevent three artillery battalions from delivering counterbattery fire most of the afternoon against reported enemy guns a hundred yards from where the Goumiers had last reported their positions.

After dark, Capt. Guido Verlet was able to pull his Tabor of Goums back from the Troina River and out of enemy fire. Shortly thereafter Verlet himself was in Capizzi to plead for a half-hour artillery concentration on enemy positions two hundred yards east of where the 4th Tabor had spent the day. This, he was sure, would enable the Goumiers finally to take Monte Acuto.34 Dubious, the artillery refused; friendly troops were too close, and their locations not altogether clear.

Meanwhile, a battalion of the 26th Infantry had moved east early that morning with the purpose of coming abreast of the other two battalions of the regiment near Monte Basilio. The battalion became lost, wandered in the hills, and finally came to rest on Monte Stagliata, some two miles west of the other regimental elements on Rocca di Mania and Monte Castagna.

This lost battalion could have been of use on Monte Basilio, which was struck in the early afternoon of 3 August, first by a heavy barrage of artillery fire, and then by Group Fullriede infantrymen. Stubborn defensive fires from the American riflemen and machine gunners, supported by effective artillery concentrations, repulsed the German effort to retake this key terrain feature. But Monte Basilio, vulnerable to enfilade fire on both faces, continued to take a pounding from Monte Acuto and from the Troina area.

Although successful in its defensive stand, the battalion on Monte Basilio was in no condition to resume the 26th Infantry’s attack to cut the highway east of Troina. During a lull that afternoon, when General Allen suggested that the 39th Infantry might move its leading battalion forward about 800 yards to Monte di Celso, Flint agreed. “There is nobody there now,” Flint said. “We can take it over if you want.”35 Yet when a company started to move toward the high ground shortly before dark, artillery and mortar fire heralded an infantry counterattack that scattered and disorganized the American unit and drove

the riflemen back to the regimental positions.

Actually, the Germans had telegraphed their intention, but the division headquarters had been asleep at the switch. About an hour and a half earlier, the 26th Infantry had become aware of German infiltration—troops “walking up the stream bed”—on its right flank. Colonel Bowen had reported this to division headquarters, but the Division’s G-3 had apparently failed to pass the information on to Flint.36

Despite its failure to take Troina by the fourth day of the attack, the division had made some important gains. The 16th and 39th Regiments, though temporarily disorganized by counterattacks, retained positions seriously threatening the town. And Bowen’s 26th Infantry on Monte Basilio could call interdictory fire on Highway 120 beyond Troina, thereby disrupting German communications.

During the evening of 3 August, General Allen ordered renewal of the attack by the units already committed and with added strength from the south against the Gagliano salient. Instructing Colonel Smith to bring forward a second battalion of his 18th Infantry, General Allen gave Smith responsibility for a zone on the extreme right flank. Smith was to control not only two of his own organic battalions, but also the 1st Battalion, 16th Infantry, already in the area. By these means, Allen hoped to execute what would be in effect a pincers movement by the two regiments on the flanks: the 18th Infantry on the south, the 26th Infantry in the north, while the two regiments in the center, the 16th and 39th, exerted frontal pressure against the town.37

General Allen would have been even more hopeful of success had he known what effect the fighting of the past two days had had on the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division. The German division had incurred heavy losses, at least 1,600 men. Furthermore, the XIV Panzer Corps had given General Rodt the last of its reserve units during the night of 3 August.38

General Hube, the XIV Panzer Corps commander, was not only watching the situation closely at Troina, he was also concerned with the sector immediately to the south where the Canadians were advancing along Highway 121. Early 30 July, following a heavy artillery preparation, Canadian troops had struck hard in a move to jump the Dittaino River, clear Catenanuova, and present the newly arrived British 78th Division with a bridgehead for the attack toward Regalbuto on the left, Centuripe on the right. As both Canadian and British troops converged against Regalbuto and Centuripe, the former fell on the evening of 2 August, the latter the following morning. The two main outposts in the German defense of Adrano thus lay in Allied hands.39

If the British pressed beyond Regalbuto and cut the Troina–Adrano road, as Hube was sure they would, the German corps commander had to face the danger that the Canadians might turn north and cut Highway 120 east of Troina. In that

case, withdrawal of Rodt’s division would be imperative.40 But as long as Rodt’s troops retained their escape route to the east, there was no reason to give up the defenses at Troina that had proved so effective. Although the Allies were seriously threatening the Etna line by 4 August they had not yet cracked it. Hube’s timetable for evacuating Sicily (although formal evacuation had not yet been ordered) hinged on holding the Etna line as long as possible, and this Hube was determined to do. As a result, Rodt’s units dug in still more firmly around Troina for what they expected might be a last-ditch stand.41

The Germans were surprisingly successful during the morning of 4 August, the fifth day of the battle for Troina. North of Highway 120, Group Fullriede was particularly aggressive in its defense. Counterattacks by infiltrating parties kept the Americans off balance and inflicted heavy casualties. South of the highway, Group Ens, perhaps not quite so aggressive in launching counterattacks, remained firm in its defensive positions. By noon, it was evident that the 1st Division needed more assistance to get the attack moving.

Help appeared from the skies. General Bradley had successfully solicited two large-scale air attacks, one scheduled around noon, the other at 1700, each by thirty-six P-51 planes. In addition, General Allen had obtained the promise of eight P-51’s to bomb and strafe Monte Acuto at 1445.42

The planes turned out to be A-36’s (modified P-51’s), but this made little difference. Throughout a good part of the afternoon, as artillery added its weight, American aircraft plastered Troina and the surrounding hills, though Monte Acuto escaped—the pilots failed to identify that target. Reactions from the ground units were uniformly enthusiastic: “Air and artillery bombardment lovely.” “The enemy is completely unnerved.” “Have captured a few Germans and they are jittery, and they seem to be attempting to give themselves up.” “It took a lot of pressure off our troops.”43

Though all four of General Allen’s regiments moved rapidly during the afternoon of 4 August to take advantage of the demoralization of German troops, the benefit proved to be only temporary. The American units could register only slight gains before meeting fire and counterattacks. One battalion of the 18th Infantry managed to dislodge the Germans from the base of Monte Pellegrino (a key strongpoint in the Gagliano salient positions) before setting up its own perimeter for the night; but try as it might, the battalion could not dislodge the Germans from the rest of the hill. North of Highway 120, two battalions from the 39th Infantry moved quickly down the slopes of Monte San Silvestro and against

some ineffectual fire reached Monte San Mercurio, about a mile northwest of Troina. The 26th Infantry finally cleared Rocca di Mania, more than two miles northwest of Troina, but when the men on Monte Basilio tried to move eastward, they ran into Group Fullriede’s last reserve, but a force strong enough to make the Americans retire to their mountain position.

The best gain had been made in the south, where part of the 18th Infantry was getting into position to roll up the Gagliano salient and thrust an attack home against the southern approaches to Troina. This development seemed promising, all the more so since the Canadians, pressing on beyond Regalbuto, had that same day crossed the Troina River and taken firm possession of a stretch of the Troina–Adrano road.

By this time, the remainder of Eddy’s 9th Division was coming into the Nicosia area preparatory to relieving the 1st Division. General Bradley had instructed General Eddy to replace Allen’s forces east of Troina so that the 9th Division could continue along the axis of Highway 120 to break the next German defensive line, expected to be uncovered in the Cesarò, area. Eager to enter the fray, yet denied maneuver room in the Troina area, Eddy, with his sights fixed on Cesarò, planned to commit Col. Frederick J. DeRohan’s 60th Infantry on the 1st Division left. With the Tabor of Goums attached, DeRohan was to make a difficult cross-country advance generally eastward from Capizzi, across Monte Pelato and Camolato; he was to debouch from the hills on the north-south Sant’ Agata–Cesarò road and be ready to attack Cesarò. By that time, Eddy hoped, the 1st Division would have cleaned up Troina so that he could commit Col. George W. Smythe’s 47th Infantry along Highway 120 for a direct advance on Cesarò. There the 47th Infantry could assist DeRohan’s enveloping attack from the north.

What Eddy envisioned was making a wide bypass of Troina on the north and striking quickly toward the next enemy defensive line. As an added dividend DeRohan’s movement, starting before the Germans had given up Troina, might prompt the Germans to loosen their hold on Troina in order to escape a trap at Cesarò. On the assumption that Allen would have Troina by nightfall on 5 August (at the end of the sixth day of attack) and that the relief could be completed that night, General Bradley directed Eddy to start moving the 60th Infantry eastward from Capizzi on the morning of 5 August. This would permit the 60th to work its way toward Cesarò while the 1st Division and the attached 39th Infantry completed the reduction of Troina.44

As the 60th Infantry, with the Goumiers attached, started its cross-country strike toward Cesarò on 5 August, the 1st Division resumed its attack against Troina. On the left, Bowen’s 26th Infantry was unable to move forward because of rifle fire and artillery shelling. Twice Bower asked for air support—once against Monte Acuto, the second time against “some guns which we cannot spot from the ground. ... Make it urgent.”45 But the missions scheduled could not get off the ground because of fog at the airfields.46

The 26th Infantry, without gaining

ground, sustained serious casualties. In the afternoon, after an estimated sixty Germans attacked Monte Basilio, only seventeen men from Company I could be located. The fighting had been hot and heavy. Pvt. James W. Reese, for example, had performed with exceptional heroism. Moving his mortar squad to a more effective position, he had maintained a steady fire on the attacking Germans. When they finally located his squad and placed fire against the mortar position, Reese sent his crew to the rear, picked up his weapon and three rounds of ammunition (all that was left), moved to a new position, and knocked out a German machine gun. Then picking up a rifle, Reese fought until killed by a heavy concentration of German fire.47

By late afternoon the 26th Infantry was in bad shape. The 2nd and 3rd Battalions, on Monte Basilio for almost three days, had been virtually cut off from supplies for much of the time and were running low on food and ammunition. Two aerial resupply missions, one by artillery observation planes on 5 August and one the following day by XII Air Support Command aircraft, failed to bring sufficient relief.48

In contrast with the 26th Infantry, Flint’s 39th Infantry made a solid gain. During the preceding night, two battalions worked their way east from Monte di Celso and Monte San Mercurio. Reaching a point about a mile due north of Troina, they turned southeast to cut the highway. When daylight came, the Germans spotted the movement. Accurate machine guns, small arms, and mortar fire in heavy volume stopped the American advance and sent the men of one rifle company back in disorganization. Using two tanks as roving artillery, the Germans pounded away at Flint’s troops. At noon, Colonel Flint ordered his men to desist from further eastward advance. It would be enough, he instructed, if they dug in where they were and did no more than threaten the eastward exit from Troina.

Late in the afternoon, eighteen A-36’s in two groups bombed east and west of Troina. Flint, thinking this was the start of another air-artillery show (although he had not been informed that one was coming off), queried Colonel Gibb on this matter. Gibb laconically answered: “Bombing unscheduled.” The division had no plans to exploit the unexpected appearance of the American fighter-bombers. The 39th remained buttoned up.49

Similarly, Taylor’s 16th Infantry spent the day trying to advance against the two key points on the ridge system west of Troina—Hills 1034 and 1006—but made no headway because it had to devote its major effort to warding off German counterattacks and digging in for cover against accurate German fire.

South of Troina, where Smith’s 18th Infantry tried to seize the dominating hills of the Gagliano salient as well as the two hills—Bianco and San Gregorio—closer to Troina, the Americans were no more successful. Heavy German fire, small counterattacks, and mine fields reduced American units in strength and prevented them from seizing the commanding ground. Rifle companies numbering

sixty-five men became common. At the end of the day, Group Ens still held the vital heights.

Despite his defensive success on 5 August, General Rodt knew that he could not hold out in Troina much longer. With his units badly depleted and his men near exhaustion, he had already requested—though it was disapproved—Hube’s permission to withdraw some 5,000 yards to a new defensive line. Rodt’s greatest concern was the threat that American units north of Troina, particularly the 26th Infantry on Monte Basilio, were exerting against Highway 120 east of the town. Sensitive to the necessity of preventing the Americans from cutting his single escape route out of Troina, Rodt had made his strongest effort north of the highway where his troops had manhandled Bowen’s and Flint’s regiments. Though he felt he had the situation under control at Troina, Rodt had nothing substantial with which to contest the wider envelopment that DeRohan’s 60th Infantry represented. Also, he was concerned with maintaining contact on his left flank with the Hermann Göring Division, which was slowly being pushed back up against Mount Etna by the British 30 Corps. Only a slight penetration as yet existed on his left flank, but the absence of German reserves on the island made Rodt doubtful that the Germans could long contain the British threat.

Because of the tense situation along the entire front late on 5 August—the greatly reduced combat efficiency of the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division, the over-all lack of German reserves, the danger of an Allied breakthrough of the Etna line in the Cesarò area, the possibility of Allied seaborne landings in his rear—Hube followed Rodt’s suggestion and decided to withdraw to a shorter line. This line, which Hube designated as the shorter bridgehead line (Guzzoni called it the Tortorici line), extended from Giarre on the east coast over Mount Etna to Randazzo, Poggio del Moro, and on to the north coast at Cape Orlando. Ordering his divisions to make a fighting withdrawal on successive phase lines, Hube hoped to gain a week in pulling back to the new line. If he could have his troops in this new position by the morning of 12 August, he would be more than satisfied.50

Guzzoni, still nominally in command of the Axis forces on Sicily (though he had surrendered most of his prerogatives on 25 July), protested Hube’s decision to start withdrawing from the Etna line on 5 August. Guzzoni thought the movement premature, particularly since the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division still held firmly in the northern sector near San Fratello. But over Guzzoni’s protests, Hube started to withdraw his forces in the eastern and central sectors of the front during the night of 5 August. In fact, on the east coast, the Hermann Göring Division began withdrawing from Catania during the evening of 4 August, leaving only a rear guard to contest British entry the following morning. The

Generals Huebner and Allen, 8 August

29th Panzer Grenadier Division was to hold until forced to withdraw by pressure.

At the conference with Guzzoni on 5 August, the Germans urged the Sixth Army commander to transfer his headquarters to the Italian mainland. Suspecting that the Germans requested this because they wanted a completely free hand in Sicily, Guzzoni asked whether the Germans intended to withdraw even beyond the Messina Strait. Though the Germans emphatically denied this, Guzzoni remained on Sicily five more days. Not until Comando Supremo charged him with the defense of a part of Calabria did Guzzoni evacuate his headquarters to the mainland.51

At Troina, with permission at last to withdraw, Rodt started to pull out his troops late in the evening of 5 August. Leaving behind rear guards to delay the Americans, he moved his forces east along Highway 120 to Cesarò. By nightfall of 6 August, Rodt’s men occupied a defensive line just west of Cesarò, and most of his heavy equipment was already on its way to Messina for evacuation from Sicily.52

The 15th Panzer Grenadier Division did not slip away from Troina without detection. American patrols late on 5 August reported Monte Acuto abandoned, German fires slackening, and even some positions no longer held. One patrol managed to reach the crest of Monte Pellegrino, earlier firmly defended, without opposition.

Despite the signs of German withdrawal, General Allen had had enough experience at Troina to be wary. He made elaborate preparations for the renewal of the attack on 6 August, the seventh day of his effort to take the town. Planners outlined harassing and preparatory fire missions in great detail. Staff members requested at least seventy-two A-36’s to bomb the last half-mile of the highway east of Troina and to strafe the road as far east as Randazzo. Yet Allen withheld the hour of the attack until noon, presumably on the basis that if the Germans were going, it was better to let them go. For the subordinate units, the missions remained much the same as they had been for the past two days. A fifteen-minute artillery concentration was to precede the attack.53

All this proved unnecessary. By dawn of 6 August it was clear that the Germans were gone. Soon after 0800, 16th Infantry

patrols were in Troina and meeting only sporadic rifle fire that was easily silenced.

Troina itself was in ruins. Only several hundred inhabitants remained to welcome the Americans, most of the others having fled to the hills. One hundred and fifty dead—civilians as well as German and Italian soldiers—lay in the highway, in the streets, in demolished houses, in the round feudal tower that had been used as a German observation post. Plaster dust and the stench of death filled the air. Rubble completely blocked one street. The water mains were broken. The main street, where it made the right-angle turn on the northeast face of the cliff, was completely blown away. A 200-pound aerial bomb lay unexploded in the center of the church.

That afternoon, General Allen relinquished his zone to General Eddy, and the 47th Infantry passed around Troina on its way to Cesarò.

General Allen also relinquished command of the 1st Division. He and the assistant division commander, General Roosevelt, turned the division over to Maj. Gen. Clarence R. Huebner and Col. Willard G. Wyman. General Allen would return to the United States to take command of another division, the 104th Infantry Division, which he would lead with distinction in northwest Europe; General Roosevelt, after serving as Fifth Army liaison officer to the commander of the French Expeditionary Forces in Italy, would earn a Medal of Honor during the Normandy invasion of 1944 as assistant division commander of the 4th Infantry Division.54

The end of the battle for Troina may well have seemed to the 1st Division commander and his assistant like a most unsatisfactory time to turn over the command of “The Big Red One” to General Huebner. For it had taken the 1st Division, reinforced with an additional regiment, a solid week to reduce defenses that had originally seemed easy enough to crack with a single regiment. In the process, the division was depleted in strength, reduced to weariness. Perhaps some of this depletion, some of this weariness, could have been avoided had the intelligence estimates of the last few days in July not been so inaccurate. Perhaps more could have been avoided had General Allen, after the failure of the 39th Infantry to take Troina on 1 August, committed more of the division’s strength, instead of waiting for two more days to do so. Evaluation of the division’s performance in the fighting at Troina might also involve an answer to the question: did the expected relief by Eddy’s incoming 9th Division contribute to the initial optimism and a possible desire to spare the troops?