Chapter 18: Breaking the San Fratello Line

On the same day (31 July) that Colonel Flint’s 39th Infantry opened the battle for Troina, Truscott’s 3rd Infantry Division arrived at Santo Stefano di Camastra to take the place of the 45th Division on the II Corps northern axis of advance.

Like Allen, Truscott faced difficult terrain and a stubborn enemy. From Licata to Palermo, the 3rd Division had operated generally in terrain where it had space for maneuver, sufficient roads and trails to accommodate supporting artillery and supply trains, and alternative routes forward. Now all this changed. Highway 113, the coastal route, is a good, hard-surfaced road, capable of carrying two-way military traffic. As Sicilian roads go, it is not crooked. But it has numerous curves, ideal places for roadblocks. On the inland side of the highway there are few lateral roads except the four that cross the mountains—usually they dead-end in the mountainous interior at typical Sicilian ridge-end towns, medieval in origin, and built on sites chosen because they were almost inaccessible. Thus, General Truscott had a choice of making his main effort either along the highway or across the northern slopes of the Caronie Mountains to outflank German coastal defensive lines. Either way, the defenders possessed the advantage: they could deny use of the highway by fire, by demolitions, and by liberal use of mines; they could delay inland movement by plotting defense positions along the several well-defined ridge lines which lie behind deep-cut mountain streams. Faced with this choice, Truscott decided that the 3rd Division would make its major effort through the mountains while units along the road would keep constant pressure on the enemy. To supply and to communicate with the units operating in the mountains, Truscott organized a Provisional Pack Train (mules) and a Provisional Mounted Troop (horses) under the command of Maj. Robert W. Crandall, a former cavalryman who had served under Truscott before the war. Some of the animals had been brought with the division from North Africa; the others had been acquired during the preceding three weeks of campaigning.1 Some had already seen action with the 179th Infantry the week before during that regiment’s advance to Mistretta.2

Despite the similarities of terrain and enemy, General Truscott had one trump card not available to General Allen. This was the possibility of amphibious landings—seaborne end runs. The enemy

Provisional pack train and mounted troops organized for 3rd Division supply and communication in the Caronie Mountains

along the north coast, almost no matter where he chose to make a stand, was vulnerable to this type of operation. As early as 30 July, Generals Patton and Bradley had taken note of this valuable military asset. In fact, they had considered an amphibious operation to assist the 45th Division in cracking the enemy’s Santo Stefano position, but enemy withdrawal had canceled this plan. By 2 August, General Patton had definitely decided to utilize his “Navy”—Rear Adm. Lyal A. Davidson’s Task Force 88—to assist the 3rd Division’s advance. But Davidson had sufficient landing craft to lift one reinforced infantry battalion, no more. Accordingly, the Seventh Army selected four tentative landing places, each behind a predicted enemy defense line, where a battalion-size amphibious end run might be executed. At General Bradley’s request, General Patton agreed to let the II Corps commander time any such operation so that an early link-up between the relatively small amphibious force and the main body of the 3rd Division would be assured. Bradley apparently felt that the Seventh Army commander might be hasty and rash in deciding missions to be executed, and he wanted the II Corps, in coordination with Truscott, to exercise full control over the forces involved.3

Enemy field of fire over Furiano River crossing site from San Fratello Ridge

Looking south over the Furiano River valley from the mouth of the Furiano River, San Fratello Ridge rising at the left. Railroad crossing can be seen in foreground, with highway crossing slightly above

For the first amphibious operations General Truscott selected Lt. Col. Lyle A. Bernard’s 2nd Battalion, 30th Infantry (which had been one of the assault battalions on 10 July), reinforced by Batteries A and B, 58th Armored Field Artillery Battalion, a platoon of medium tanks, and a platoon of combat engineers. The first mission of the task force was to plan a landing near the small town of Sant’Agata east of the Furiano River. Immediately beyond the Furiano River (fifteen miles east of Santo Stefano) lay the San Fratello ridge. If the Germans were going to fight anywhere on the north coast, Truscott judged that this would be the place.

The switch of American divisions gave General Fries’ 29th Panzer Grenadier Division ample time to retire along and near the coast to the Etna line, which ran roughly along the San Fratello–Cesarò road. The withdrawal was hampered, however, by heavy American artillery and naval gunfire and by repeated Allied air strikes. Naval gunfire bothered Fries’ units most, as Admiral Davidson’s warships busied themselves with numerous fire support missions along the coast from Santo Stefano eastward to Cape Orlando. To delay the 3rd Division’s advance to the new line, Fries deployed strong rear guards, units which included Italian troops.

By morning of 3 August, Fries’ outpost line had been driven in. The 15th Infantry, with the 2nd Battalion under Maj. Frank J. Kobes, Jr., operating on the road, and the 3rd Battalion under Lt. Col. Ashton Manhart paralleling the advance on the slopes of the mountains, hit the Furiano River during the afternoon. Here, the 2nd Battalion came under heavy fire, found the river bank and all likely crossing sites heavily mined, and halted. Though Colonel Johnson, the regimental commander, sent his Ammunition and Pioneer Platoon and the Antitank Company’s mine platoon forward to clear lanes, heavy fire from across the river put a stop to these efforts. It was obvious that a bridgehead would have to be established before the mines could be cleared. In preparation for seizing such a bridgehead the next morning, Johnson moved the 1st Battalion (Lt. Col. Leslie A. Prichard) up on line with, and inland from the 2nd Battalion. Farther inland some three miles, the 3rd Battalion had also arrived at the river, some two miles west of the town of San Fratello, after a slow and grueling march across deep gorges and over mountain trails so precipitous that several of the mules carrying rations and ammunition had lost their footing and tumbled to their deaths hundreds of feet below.4

At San Fratello, Fries had terrain scarcely less formidable than Rodt had at Troina, where, on this same day, the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division was throwing back every 1st Division thrust. Near its mouth the Furiano River is wider than most Sicilian rivers. Completely dominated by the ridge beyond, the river bed provided the Germans with a wide field of fire, as well as an ideal setting for liberal use of mines. The San Fratello ridge across the river has a seaward face about a mile and a half long, rising from a point six hundred yards from the beach and reaching a climax in the stony plug of Monte San Fratello, a rugged, flat-topped mountain some 2,200 feet high. The ridge then descends into a saddle to the town of San Fratello, a thousand yards farther south, before rising again into the Caronie Mountains. The road leading

southward to Cesarò, one of the four transverse roads across the mountains between Santo Stefano and Messina, twists and turns up the northeast angle of the ridge, and about halfway up turns west directly across the end of the ridge. It continues on this course for about a mile then turns south around the west face of Monte San Fratello against a sheer rock cliff, hairpins up the ridge crest, and then passes through the town. It is about eight miles by road from the coast to the town; it is another sixteen miles to Cesarò.

Along the entire face of the San Fratello ridge, pillboxes, trenches and gun emplacements made things tough for the 3rd Division. Particularly strong was a pillbox area near San Fratello, a strongpoint that extended along the road and up the mountainside against the cliff. Connected by trenches, these pillboxes blocked the approaches on the road from any direction and completely covered the Furiano River below. South of San Fratello, the ridge rises up as distinct as a camel’s back and is covered with large boulders and rock fences. Not far west of the town—where Manhart’s 3rd Battalion ended its march on 3 August in a state of exhaustion—the Nicoletta River comes into the Furiano River from a southwesterly direction. Between the two rivers, the Nicoletta ridge runs north and south along the approaches to the Furiano River. This high piece of ground, almost indispensable to an attacker before he could jump the Furiano River, was enfiladed from the north by Monte San Fratello, from the south by higher ground along the Cesarò road.

Just west of the Furiano River, Highway 113 passed southward around a prominent spur, about one-third the height of Monte San Fratello, and crossed the river on a high stone-arched bridge, now blown from end to end. From the bridge north to the sea, a distance of about a mile, the river bed widened out. From the high ground east of the river the defenders could observe the narrow coastal plain as far west as Caronia. This advantage the Germans put to good account, and in the days ahead accurate enemy artillery fire played havoc with any movement eastward along the highway. Inland, a flanking movement might be covered from the enemy’s view, but the roughness of the terrain would make progress slow and coordination difficult. This was by far the toughest enemy position the 3rd Division had as yet encountered in Sicily. Like Middleton’s men on Bloody Ridge, Truscott’s regiments were to learn to stay “with the damn fight till it’s over.”5

At 0600 on 4 August, after spending the night in developing the enemy’s defenses along the river, the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 15th Infantry, jumped off in the attack. A scheduled thirty-minute artillery barrage failed to come off because the supporting artillery battalions had displaced forward only during the night and had had no chance to register. On the left, Kobes’ 2nd Battalion tried first to cross the river to the left of the demolished highway bridge, between the bridge and the sea. Within forty minutes the battalion was stopped cold by heavy enemy fire pouring down from the ridge, and by the dense mine fields in the river bed. For almost four hours the battalion tried to get across the open area. Every attempt failed. Even naval gunfire support and the smoking of Monte San Fratello did little to help.

Highway 113, shown running west along the north coast line to Cefalù from the juncture with the San Fratello–Cesarò road at lower left

Looking north over the San Fratello–Cesarò road. Cesarò (left center) and Highway 120 are at the southern terminus of the San Fratello road

San Fratello Ridge from the highway. The town of San Fratello is at upper right

In the middle of the afternoon, Kobes changed the direction of his attack, lunged to the right of the bridge site, and sent two companies to attack Hill 171, just across the river and an apparent German strongpoint. All went well on the near bank. But when the two companies came into the open river bed, the Germans met them with a withering hail of machine gun and mortar fire. A few men of the forward platoons managed to get across the river to huddle under the steep river bank. At dark, Kobes called them back. Prichard’s 1st Battalion suffered much the same fate; it too had been unable to get across the river.

It had been a costly day for the 15th Infantry—103 casualties, no ground taken. But this action showed General Truscott that the San Fratello ridge was not to be taken by a frontal attack executed by only two infantry battalions, no matter how much fire support those battalions were given.

The next day (5 August) turned out to be more a day of preparation than of progress. Truscott decided to shift the division’s main effort to the right, through the mountains, to strike at the San Fratello ridge from the south and roll the defenders into the sea. Truscott ordered Colonel Rogers to take the two remaining battalions of his 30th Infantry to the area then occupied by the 3rd Battalion, 15th Infantry, west of San Fratello, to attack the next day with all three battalions to take the town and cut the road to Cesarò. At the same time, the two 15th Infantry battalions near the coast were again to storm the west slope of Monte San Fratello.6

Across the river, however, General Fries was already taking steps to evacuate the San Fratello ridge. The withdrawal of the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division from Troina during the night had uncovered Fries’ left flank. Farther south the British 78th Division was nearing Adrano, the key to the center of the Axis front, while on the east coast, the British 50th Division had entered Catania. The entire central and eastern sectors of the front were pulling back slowly in accordance with General Hube’s decision to form a shorter defensive line nearer Messina. Though American units on the south had not yet reached the Cesarò road, General Fries feared that they would do so shortly, thus making an envelopment of his San Fratello positions possible. Too, ever since the commitment of his division on the north coast, Fries had been worried about the possibility of an Allied attack from the sea behind his main lines of resistance. He had tried to provide some safeguard against such an attack, but he could never spare more than one battalion for this purpose. It was a lengthy coast line with numerous suitable landing places, and Fries knew he could not guard them all. He had instructed all service troops and other units committed on or near the coast to guard against a surprise Allied landing, but even this measure afforded little real security; it only provided a watch at the most dangerous points.

Because of the lack of adequate roads through the mountains, Fries’ units south of San Fratello, as well as some of those in Rodt’s sector, had to use the Cesarò–San Fratello road to reach the coastal highway to withdraw to the east. Realizing this, Fries kept one reinforced battalion in the Monte San Fratello positions to hold until all troops and vehicles to

the south had passed around the mountain on their way to the east. He also deployed a reinforced Italian regiment from the Assietta Division to hold the ridge line south of the town. The remainder of the two divisions, less the artillery which stayed in position to cover the withdrawal, began moving eastward during the night.7

General Truscott had not fully appreciated the difficulty of the mountainous terrain over which the 30th Infantry would be operating. What was supposed to be a coordinated attack on the morning of 6 August turned into a series of un-coordinated battalion-size thrusts.

At the highway bridge, following a half-hour artillery and smoke preparation, both Prichard’s 1st Battalion and Kobes’ 2nd Battalion, 15th Infantry, jumped off at 0600. The belts of German fire proved to be so effective that progress was limited to only a few yards. Prichard’s battalion on the right managed to get across the river and to within a thousand yards of the Cesarò road. But this cost heavy casualties and by 1400 the battalion was barely hanging on. On the left, Kobes’ battalion met much the same fate trying to take Hill 171. Company G, followed by Company F, crossed the river and went 600 yards up the slopes of the hill before the Germans began firing automatic weapons, following this up with deadly accurate mortar fire. If the small arms fire lacked the intensity of previous days, the German mortar fire proved to be as effective as before. Company G stalled.

A flanking maneuver by Company F offered more promise. Swinging around the stalled Company G, passing along the river bank for a short distance, Company F turned right and advanced up a draw toward a German outpost line. Though eventually spotted, the troops were close enough to leap into the German positions before heavy fire could be brought to bear. But even this success was not sufficient to drive the Germans from the crest of the hill. While reorganizing in a small grove of trees preparatory to going for the top, Company F was hit by a small counterattack supported by mortar fire. The last two company officers were hit, and though the company, under its noncommissioned officers, beat off the German threat, it could not get moving again.

Kobes, feeling that his two companies could not gain the hill, sent word for them to hold until nightfall, then to pull back across the river. Despite strong German combat patrols that ranged the slopes of the hill that night, Companies F and G, after several fire fights, recrossed the Furiano where the 2nd Battalion, 7th Infantry, had moved up to cover their withdrawal. Just a little earlier, the 1st Battalion had also recrossed the river. At a cost of thirty dead and seventy wounded, the 15th Infantry had failed to gain any ground.

While this action was taking place near the highway bridge, Colonel Rogers’ attempt to roll up the German flank also bogged down. It had taken Colonel Rogers’ two battalions until 2200 on 5 August to get even as far as a forward assembly area, well to the west of the Nicoletta River. Colonel Manhart’s 3rd Battalion, 15th Infantry—attached to Colonel Rogers for this operation—had crossed the Nicoletta River earlier that evening and had gained a foothold on the Nicoletta ridge overlooking the Furiano River, a good position from which to start

an assault on San Fratello at the prescribed time the following morning. Having gained this position, Manhart sent guides back to lead Colonel Rogers’ two 30th Infantry battalions to the ridge.

When the guides arrived, Lt. Col. Fred W. Sladen, Jr.’s 1st Battalion and Lt. Col. Edgar C. Doleman’s 3rd Battalion prepared to move forward. The early morning hours turned out to be nightmarish for both battalions. Leaving their assembly area at 0200, the battalions moved slowly through murky darkness preceded by Manhart’s guides. Unfortunately, the guides had trouble picking their way through the woods and down the rocky ridges, and the 3rd Battalion, leading the way, soon became badly strung out. Not until 0530 did the head of Doleman’s battalion arrive at Manhart’s positions on the Nicoletta ridge; it took another hour and a half (until 0700) for the rest of the battalion to come in. Sladen’s 1st Battalion had even tougher going. Its guides lost their way, and the battalion wasted thirty minutes backtracking to the correct trail. After several more delays caused by the rough terrain and by the need to wait for the mule train to catch up, the head of the 1st Battalion finally arrived on the west slopes of the Nicoletta ridge—south of the other two battalions—at 0630. But not until 0900 did Sladen have all of his men together.

In the meantime, Manhart’s battalion had jumped off at 0730. Despite heavy enemy fire, it reached and crossed the Furiano River, and began working its way up Hill 673, the key to the enemy’s ridge positions on the south. It got only part way up the southern slopes of the hill before being stopped by enemy fire. As soon as Manhart’s battalion cleared the ridge, Doleman began to move, echeloned to the right rear. But Doleman’s battalion was delayed an hour when one company strayed off course and was punished severely by enfilading fire along the Nicoletta ridge. At 0900, Doleman’s battalion finally crossed the Nicoletta ridge and went down the eastern slopes toward the river. Below the crest the going was easier. A crossing was made and Doleman came up on line with the 15th Infantry battalion. Here it too was stopped by enemy fire. Though Manhart finally managed to get one platoon to the crest of the hill later in the afternoon, it was promptly forced back by the Italian and German defenders. At midnight, the two battalions still lay along the lower slopes of Hill 673.

Sladen’s 1st Battalion, 30th Infantry—the farthest to the right of the three battalions—was out of touch with the other two American units for most of the day and had little idea of what was happening on its left. At 0930, Sladen finally was able to send his men up and across the Nicoletta ridge, two companies leading, two companies behind. But as with Doleman’s one company, enfilading fire from Monte San Fratello and from positions south of the Nicoletta ridge played havoc with the companies. For almost an hour the battalion suffered under a rain of heavy explosives. Both leading companies became badly disorganized. Finally, one of the companies, plus about half of the other one—the rest of the unit had gone astray while moving through thick brush—reached the Furiano River, The depleted company never did get across because of heavy artillery fire and it remained for the rest of the day in a draw at the bottom of the ridge. The other company did get across the river at 1530, got to within six hundred yards of the

crest of the ridge, but could progress no further. Since the company’s effort was isolated, Sladen called the men back.

Several hours before this, General Truscott, after touring the area in which the 30th Infantry was operating and realizing just how difficult the terrain was, decided to outflank the San Fratello line by sea: to land Colonel Bernard’s small task force behind the enemy’s line in conjunction with a renewal of the division’s attack the next morning.8 Just after noon, Truscott ordered Bernard’s force to an embarkation point a mile west of Santo Stefano. Unfortunately, the Luftwaffe picked this particular time to interfere with Truscott’s operations. Even as Bernard marched his infantrymen, artillerymen, and engineers toward Santo Stefano, four German aircraft swooped out of the sky over Santo Stefano’s beaches, bombing and strafing the loading area. Although two of the attackers were shot down by antiaircraft fire, one LST was badly damaged. Because this was a key landing vessel, General Truscott postponed the amphibious end run for twenty-four hours while the Navy brought up another LST from Palermo.9

With the amphibious end run postponed for at least a day, General Truscott turned again to the job of keeping the pressure on the San Fratello defenders, hoping that the limited successes gained on the far right might be exploited. He sent General Eagles, the assistant division commander, to supervise the 30th Infantry’s operations on that flank, and he ordered Colonel Sherman’s 7th Infantry into position along the Furiano River near the coast to exploit any successes the 30th Infantry might gain.10

Both Manhart’s 3rd Battalion, 15th Infantry, and Doleman’s 3rd Battalion, 30th Infantry, launched another attack on Hill 673 early in the morning of 7 August. This time, Doleman’s battalion made the main effort. Again there was difficulty in maintaining contact, and again units became disorganized.

Using one platoon from Company I in the lead—the rest of the company had disappeared during the previous day’s fighting—and pushing Company K after it, Doleman started his attack at 0530. Almost immediately the infantrymen received heavy fire. As daylight broke, Doleman could see that the face of the hill on which his two companies were trying to move forward was subject to enfilading fire from the south. This fire, combined with the defenses on the hill itself, made an advance to the top seem most unlikely. Doleman accordingly called off these two companies, started them back down the hill, and dispatched his last unit, Company L, to work up the hill farther to the west. But during the withdrawal, the two forward units became even more scattered, so that by the time they returned to their starting position, Doleman could count—in addition to Company L—only one platoon from Company K, one squad from Company I, and two platoons from Company M. Company L attacked up the west slopes of Hill 673 only a short distance before being halted by heavy enemy fire pouring

down from the summit. Doleman left the company on the slopes while he tried to reorganize his battalion for another attack.

Late in the afternoon, the two battalion commanders, Colonel Rogers, and General Eagles worked out a new plan for a coordinated attack on Hill 673. Manhart agreed to turn over to Doleman his Company K and a mortar platoon, and to send his other two companies in on Doleman’s left when the attack went off. Doleman was to make the main effort, this time just before total darkness set in.

At 1930, the battalions jumped off, with Company L, 30th Infantry, leading the way. Despite heavy enemy fire, the rifle companies moved slowly up the slopes, maintaining contact with each other, fighting a truly coordinated battle. The line that had held for so long began giving way and finally cracked. Just before midnight, Company L, 30th Infantry, gained the crest of the hill, closely followed by the rifle companies of the 15th Infantry. Once on top, the Americans began digging in, as Doleman and Manhart pushed up their supporting heavy weapons companies to provide close fire support.

This proved fortunate because the Italians and Germans, under a withering forty-five minute artillery barrage, moved back against the two depleted American battalions on Hill 673. For almost two hours, a savage, close-in, sometimes hand-to-hand battle raged across the top of the hill. Manhart and Doleman committed everything they had in the effort to hold on, even distributing machine gun ammunition to the riflemen to keep them firing. Grenades, bayonets, even rocks, played a part in the struggle. Finally, at 0200 on 8 August, the enemy pulled away from the hill, going north toward the coast.11

To the south of Hill 673, an area from which enemy fire had plagued Doleman and Manhart all day, Sladen’s 1st Battalion, 30th Infantry, had tried hard to cover the other units by going for the high ground to knock out the enemy guns. The battalion’s attempt was unsuccessful, as the men from the other two units could testify. It took Sladen’s rifle companies until the middle of the afternoon to get organized, and even then Sladen could not find all of his small units. Except for a platoon from Company C that managed to get a short way beyond the river and annoy the Italians along the ridge—taking a beating for its pains—and for another patrol that eventually contacted the units on Hill 673, the 1st Battalion, 30th Infantry, did little to assist in reducing the San Fratello positions.

By this time, however, Colonel Bernard’s small task force was nearing the beaches east of Sant’Agata. At noon, 7 August, General Truscott, with General Bradley’s approval, had decided to launch the once-postponed end run early on the morning of 8 August. Sherman’s 7th Infantry was to penetrate the enemy’s defenses on the coast to effect the link-up, which Truscott hoped would take place before noon.12

At 1700, then, Bernard’s force again moved from its bivouac area to the beaches west of Santo Stefano. Another LST had arrived from Palermo. But again the Luftwaffe almost knocked out the operation. Just before the ground troops began

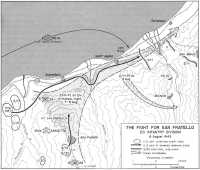

Map 6: The Fight for San Fratello 3rd Infantry Division 8 August 1943

loading, German aircraft dropped out of the clouds in a bombing and strafing attack aimed at the beached landing craft. This time the Luftwaffe did not succeed. Though an LST and an escort vessel were damaged, hurried repairs made the LST sufficiently seaworthy to go on with the operation. At 1940, the ten landing craft pulled away from the beaches as Admiral Davidson’s two cruisers and six destroyers moved in to provide cover.

At the San Fratello line, despite shelling from Davidson’s warships during the day, General Fries’ rear guards had begun pulling out of their positions, covered by the defenses on Hill 673. That evening, one of the warships laid a barrage on the highway bridge across the Rosmarino River, some two and a half miles east of Sant’Agata, and set off demolitions which the Germans had placed to blow the bridge after passage of the last group of defenders from the San Fratello ridge. Since the river bed had already been heavily mined, the withdrawal of the rear guard units had

to be halted until engineers could clear a route. (Map 6)

By 0300, German engineers completed the bypass across the river. The 2nd Battalion, 71st Panzer Grenadier Regiment, plus part of the Assietta Division’s 29th Infantry Regiment (most of this regiment was left along the San Fratello ridge to delay American follow-up movements) started across the bypass. At this very moment, Bernard’s infantrymen came across the beaches.

According to General Truscott’s concept of Bernard’s operation, the amphibious force was to land near Terranova (east of the Rosmarino River), attack inland to seize Monte Barbuzzo (about a mile to the southwest), cut the coastal highway, and trap the defenders holding the San Fratello ridge. At 0150, 8 August, the small naval force hove to off the coast, its presence undetected. Companies F and G, 30th Infantry (the first wave) and one tank platoon and an engineer platoon (the second wave) immediately began loading into LCVPs from the two LSTs. At 0230, the two waves started their final run in from about six thousand yards out. The LSTs and the one LCI (which carried Company E) followed to about 1,500 yards offshore, where the LSTs launched sixteen Dukws loaded with Bernard’s headquarters personnel and Company H.

At 0315, Companies F and G touched down and started inland toward the high ground less than a mile away. The other waves followed at fifteen-minute intervals, with all troops and vehicles unloaded by 0415.

Surprise was complete, but reaction was swift from the German battalions spread from the Rosmarino River all the way back to San Fratello. Company G on the right drew the first German fire just after crossing the railroad, some two hundred yards inland. A short while later, Company F jumped a small group of Germans drowsily awakening from a sound sleep. By 0430 the beach was secured, and the lead companies began moving inland for what they thought was Monte Barbuzzo. But Colonel Bernard now realized that his force had not landed where it was supposed to land. Rather than being east of the Rosmarino River near Terranova, he had been put ashore west of the river, nearer Sant’Agata, and he began to change his plans. Since his force could not get to Monte Barbuzzo before the 7th Infantry jumped off to link up, Bernard determined to occupy high ground on both sides of the river. This would give him good defensive terrain and would also provide cover for the oncoming 7th Infantry.

At just about this time, however, the Germans launched their first counterattack. Part of the German battalion had already crossed to the east side of the river, but the elements in and near Sant’Agata, delayed by the demolished bridge, now found themselves between the 7th Infantry—which had jumped off at 0600—and Bernard’s task force. Fighting in two directions, the Germans sent a small infantry detachment supported by two Italian Renault and two German Mark IV tanks to open a route to the east along the coastal highway.

It was a short-lived effort. Bernard’s armored field artillery batteries and the platoon of medium tanks took the German counterattack under fire and quickly destroyed both Italian and one of the German tanks. At this, the Germans pulled back into Sant’Agata. The American artillery pieces and the tanks moved

Sant’Agata from the seaward side of San Fratello Ridge. The view follows Highway 113 along the coast past Sant’Agata (middle distance) to Cape d’Orlando (top center). The town of Acquedolci is at extreme left

into position in a lemon grove north of the highway. From here they could cover the coastal road east and west.

Meanwhile Company G, having finished off the small pocket of German resistance which had been opposing its advance, moved up to the highway. One platoon established a roadblock covering the eastern exits from Sant’Agata, another took up security positions around the artillery and tanks, while the remainder of the company established a block on the secondary road which winds inland to Militello. At the same time, Company F fanned out toward the Rosmarino River, crossed it without difficulty, and secured the high ground on the east bank blocking the highway and the trail which leads inland to San Marco d’Alunzio. Both of Company H’s machine gun platoons went into position to cover Company F’s right flank.

Hardly had these dispositions been completed when the Germans, trying to find an inland route around Bernard’s coastal positions, struck at Company F. One German group with two motorcycles, a vehicle loaded with cans of gasoline, and two troop carriers filled with soldiers, moved down the trail from San Marco. At the same time, another small column came down the coastal highway from the east. With Company H’s machine guns sending out steady streams of flanking fire at both German columns, Company F held fast. The German gasoline vehicle was hit and burned; all other German vehicles were put out of action. Again the armored artillerymen came into action. This combination of American fires proved too much. As the German column on the coast road pulled back toward Terranova, a few Germans from the San Marco column managed to get past Company F’s roadblock and to escape to the east.

Bernard’s third rifle company, Company E, met problems of a different nature. Late in receiving Bernard’s change of plans, the company had moved inland from the beaches toward what the company commander mistook for Monte Barbuzzo. But in the rough terrain, the company broke in half. Two of the rifle platoons stayed with the company commander; the other rifle platoon and most of the weapons platoon went off to the south, still moving inland toward what the rifle platoon leader thought was his objective. The company commander then learned of Bernard’s change of plans and he took his two rifle platoons to a position on Company F’s right flank and helped that company fend off the German counterattacks. The rest of the company, which did not learn of the change in plans, continued up the river bed and finally turned east, well inland from the rest of the battalion. The men entered San Marco at 1130, passed through, and climbed up to a high ridge about a mile northeast of the town. This the platoon leader took to be Monte Barbuzzo, and dug in to hold on until the rest of the battalion arrived.

At San Fratello, meanwhile, the thinning out of the German and Italian defenders made the task of clearing the ridge a relatively easy one for the 7th Infantry. By 1130, the 2nd Battalion, 7th Infantry, was in Sant’Agata after overcoming the remnants of the small force that had previously tried to break out of Bernard’s trap. What was left of the 2nd Battalion, 71st Panzer Grenadier Regiment, moved inland to circle past the American block east of town. At 1230, 7th Infantry patrols made contact with Bernard’s Company G east of Sant’Agata. By this time,

Plasma being administered to a wounded soldier in a first-aid station in Sant’Agata

too, Colonel Rogers’ 30th Infantry, with Manhart’s battalion still attached, was in San Fratello and on Monte San Fratello. This day, the Italians did not seriously contest the American advance. Either because they knew they were being left behind by the Germans, or because they had fought themselves out, the Assietta men surrendered in droves, almost a thousand to Doleman’s battalion alone.

For Bernard’s Companies E, F, and H, the fighting was not over, for they lay in the line of German withdrawal to the east. Concentrating on the hill mass in and near San Marco, the Germans, usually in small parties, pushed continuously at the three American companies, and at the two American platoons northeast of San Marco. Sometimes small enemy counterattacks came down the coastal highway from the east, in an evident attempt to coordinate attacks with withdrawals inland. Eventually, except for about one company and a few vehicles, the German battalion succeeded in making good its escape.

Truscott’s first amphibious end run, while achieving surprise, had failed to cut off the German 29th Panzer Grenadier Division. Most of that division had already retired by the time Bernard’s force landed. At best, the end run deprived the Germans of the use of the Rosmarino River as a defensive phase line. It probably

San Marco D’Alunzio, with the mouth of the Rosmarino River at left center and with railroad bridge just visible

did encourage the Germans to give up the San Fratello ridge a few hours earlier than they had intended. Even a landing on the correct beaches east of the Rosmarino River would have done little better.13

Late in the afternoon of 8 August, the 7th Infantry closed up to the Rosmarino River. That evening it resumed the advance along the north coast road.