Chapter 16: Storage and Distribution

Growth of CWS Storage Activities

During the months before Pearl Harbor, new logistics responsibilities assigned to the Chemical Warfare Service led to major changes in storage facilities. The principal problems at the beginning of 1941 had been the storage of mobilization quantities of gas masks (and, to a lesser extent, the storage of toxic gases). The Army’s September 1941 call for CWS procurement of incendiary bombs and 4.2-inch mortar shells introduced a whole new set of storage needs, and greatly enlarged the scale of facilities planning. There could be no storage of bombs and shells in urban warehouses, nor was there space at Edgewood for the many new magazines which would be required.1 As early as the winter of 1940-41 the CWS had to lease large warehouses in Chicago and Indianapolis for storing items delivered by contractors, and the Indianapolis installation was subsequently (April 1942) to become a full-fledged depot. But far more than this was needed. New depots had to be quickly planned. The first was an addition to the recently authorized CWS Huntsville Arsenal which the Army was building in northern Alabama. Action for this facility, the future Gulf Chemical Warfare Depot, began in September 1941 with an authorization for the transfer of 282,000 square feet of proposed toxic gas storage yard construction from Edgewood to Huntsville.2 In November the Army informed the OC CWS that funds would be available to provide storage for 40,000,000 four-pound incendiary bombs. The planned Huntsville depot gained half the

number of magazines needed to fill this requirement, while the remainder was scheduled for construction at Pine Bluff, Ark., like Huntsville the site of a new CWS arsenal.3 During 1942 the storage area at Pine Bluff became the nucleus of another new depot, Midwest.

As soon as the country was actually at war, the Chemical Warfare Service took steps to provide itself with a major depot in the far west. The preferred location was the Salt Lake City area, and a desert valley some fifty-seven miles southwest of the city, in Tooele County, Utah, was selected in February 1942. The new facility, designated Deseret Chemical Warfare Depot, was under construction by the summer of 1942. Its principal function was to serve as another storage center for bombs, mortar shells, and toxics.4

Within a year of the attack on Pearl Harbor, therefore, the wartime storage requirements of the Chemical Warfare Service were well on the way toward being matched by Chemical Warfare facilities. In addition to the prewar storage areas at Edgewood and Indianapolis, new depots were virtually complete at the sites of the Pine Bluff and Huntsville Arsenals, while the Deseret Depot was being hurried into existence. Deseret began its active storage operations in October 1942, despite the fact that construction was still underway; the depots at Pine Bluff and Huntsville had been operating since summer. From some 2,500,000 square feet of storage space in June 1942, the total available to the CWS jumped to 19,500,000 square feet by the end of 1942 and to 23,000,000 square feet by the following June.5

With the activation of the new depots the CWS depot system consisted of five branch depots—Eastern (Edgewood), Gulf (Huntsville), Midwest (Pine Bluff), Indianapolis, and Deseret—and five chemical sections of Army Service Forces depots—Atlanta, Memphis, New Cumberland, San Antonio, and Utah.6 The missions of these installations varied considerably. The Indianapolis Depot became in effect (and eventually in name) a national control point for CWS spare parts.7 The other branch depots had in common a responsibility for reserve storage of CWS gen-

Table 9—CWS gross storage space in operation, 1945

[In Thousands of Square Feet)

| Warehouse | Shed | Igloo Magazine | Toxic Yard | Open | Total | |

| Totals | 3,866 | 107 | 1,656 | 20,632 | 3,257 | 29,518 |

| Eastern CWD | 306 | 13 | 115 | 258 | 188 | 880 |

| Indianapolis CWD | 233 | 78 | 311 | |||

| Gulf CWD | 708 | 624 | 868 | 1,185 | 3,385 | |

| Midwest CWD | 134 | 3 | 486 | 1,453 | 445 | 2,521 |

| Deseret CWD | 78 | 304 | 18,053 | 631 | 19,066 | |

| Northeast CWD | 13 | 90 | 132 | 235 | ||

| New Cumberland ASFD | 380 | 32 | 301 | 713 | ||

| Atlanta ASFD | 212 | 9 | 264 | 485 | ||

| Memphis ASFD | 254 | 49 | 5 | 16 | 324 | |

| San Antonio ASFD | 161 | 6 | 2 | 169 | ||

| Utah ASFD | 568 | 10 | 17 | 15 | 610 | |

| Chicago Warehouse* | 247 | 247 | ||||

| New York Warehouse* | 216 | 216 | ||||

| Hanford (Cal.) Warehouse* | 68 | 68 | ||||

| Independence (Cal.) Warehouse* | 68 | 68 | ||||

| San Francisco POE† | 89 | 89 | ||||

| New York POE† | 131 | 131 |

* CE, Quarterly Inventory, Sponsored, and Leased Facilities 31 Dec 44.

† Hemleben, CWS Activities at Ports of Embarkation, pp. 42, 206, 213. Approximately 15,000 sq. ft. of CWS warehouse storage space was in use by the Port Chemical Officers at the smaller Porte of Embarkation.

Source: ASF MPR-2-H, 31 Mar 4S, p. 39, except as noted.

eral supplies, but their main mission was the handling of chemical ammunition and toxics for zone of interior distribution, shipment to Ports of Embarkation, and reserve storage. Distribution of general supplies, both for zone of interior installations and the Ports of Embarkation, was handled in the main by the Chemical Sections of the ASF Depots, which also distributed training ammunition to their local Service Commands.8

One of the early concerns of the new Headquarters, Services of Supply, in the spring of 1942 was supervising and standardizing Technical Service depot activities. Immediately upon its activation the SOS called upon a group of commercial warehousemen to help solve Army warehousing problems. This group, working at the San Antonio General Depot, introduced a number of innovations into Army storage practices. Among these were the reduction of aisle space to a minimum by eliminating inventory aisles, and the mechanization of materials handling through the

use of fork-lift trucks and palletized loads.9 The CWS belatedly profited from the lack of peacetime expansion of storage facilities in that it could build the new depots along lines of contemporary storage practices and wartime Army requirements. At the prewar Eastern Depot at Edgewood storage space was distributed among a number of small buildings, all with floors at ground, rather than boxcar, level. The new CWS depots, on the other hand, were designed for more efficient concentration of storage, within limits of safety, and all had floors at boxcar level. The savings in aisle space and labor made possible by the new Army guidelines promised to be considerable.10

The mechanization of materials handling at CWS depots began on a small scale during the summer and fall of 1942, in accordance with SOS policy and directives. The process of change was slow at first. Indianapolis Depot was using half a dozen fork-lift trucks for stacking materiel as early as July 1942.11 Gulf Depot, which had begun operations on “whiskey and manpower” in the spring of 1942, received its first fork-lift trucks in October, along with some warehouse tractors.12 Midwest and Deseret were operating fork-lift trucks by the spring of 1943, but Eastern Depot, with its complicated physical layout, did not begin this phase of mechanized storage until February 1944.13 Northeast Depot, activated in the spring of 1944, well after the early days of mechanization, used fork-lift trucks from the outset.14

The fork-lift truck made possible a number of labor- and space-saving advances in storage techniques. Chief of these was the palletized load, a unit of storage consisting of a pallet or wooden platform of a size to hold a given quantity of material, and built to leave clearance underneath for the forks of the fork-lift truck. Palletized loads, capable of being moved quickly into place with the fork-lift trucks, could be stored to considerable heights without danger of damage, thus making possible more economical use of space as well as of time and labor.15 Fork-lift trucks were also used in

Boxed cans of decontaminating solution stacked on pallets, wooden platforms built to leave clearance underneath for the forks of the fork-lift truck.

conjunction with many jigs, booms, and claw devices, most of them on-the-spot expedients, to improve the handling of bulky items. Deseret had a jig and boom attachment to the fork-lift truck in operation for unloading freight cars by October 1943. Jigs for simultaneous handling of up to nine 55-gallon drums of toxics were in use there during 1944, and similar methods came into use for loading the awkward incendiary bomb clusters.16

By 1944 the use of mechanized handling equipment had become general in CWS depots, and the savings in man-hours began to loom large. Eastern Depot found that the 40 man-hours previously needed to unload a boxcar could be cut to 20 or less, with 5 men doing the work of 10.17 Deseret cut crew time for the unloading of 100-lb incendiary clusters from 5 hours to 1 hour per car by using fork-lift trucks with homemade jigs.18 But fork-lift trucks brought problems as well as savings. Eastern Depot, which had never been built for mechanized handling equipment, frequently found itself in difficulties on this score. Its sixty-odd ground-level storage structures, scattered over two main areas a mile and half apart, made it hard even to get trucks from building to building, for they were not designed for cross-country operation. The trucks ultimately had to be mounted on low trailers constructed for the purpose, and towed from place to place by tractor. The depot also found that it needed an unusually large number of pallets if enough were to be on hand in any given area when required. By 1945 there were no fewer than 35,000 pallets of various sizes on the depot grounds.19

Storage and Transportation of Toxics

The problems of handling war-swollen stocks of general supplies by up-to-date methods came upon the CWS suddenly, but the task of storing items such as toxic agents was hardly new. The methods for storing and handling agents in bulk had been worked out during and after World War I by Edgewood Arsenal. The principal packaging device for toxics was the ton container, a steel cylinder with a capacity of 170 gallons (about 1900 pounds in the case of mustard). These were kept in open storage, resting horizontally on tracks designed to keep them off the ground and assure free circulation of air.

Edgewood had developed a deep respect for the problems inherent in handling and storing toxic agents and had worked out special techniques for testing, cleaning, and handling toxic containers. Men classified as toxic gas handlers had demonstrated an aptitude for the work and completed a special training course. This experience with a training program proved its value in another way after Pearl Harbor, when the depot at Edgewood found itself obligated to train cadres of toxic gas handlers for the new depots under construction.20 Midwest Depot, for example, sent seven enlisted men to the course at Edgewood in the summer of 1942 as the first step in getting its projected toxic yard into operation.

With the exception of Indianapolis, the new depots were meant to assume most of the responsibility for the storage of toxics. While Eastern was reaching its wartime maximum of some quarter of a million square feet of toxic yard space, its younger counterparts were hurrying to completion toxic yards which multiplied Eastern’s size many times over. Deseret alone had a toxic yard potential of over eighteen million square feet, and Midwest and Gulf had 2,300,000 square feet between them. But in the early days of wartime production it sometimes seemed as if_ storage space would never catch up with the demand. At Midwest Depot in 1942 the first shipment of toxics-525 ton containers of mustard—arrived just in time to fill the storage tracks available, and for the next eleven weeks construction of additional trackage was matched week after week by fresh shipments.21 Shipments of toxics into Deseret became necessary in October of 1942, though the depot had been only four months under construction. Over two thousand tons of mustard were received and stored there by mid-November, though most of the necessary mechanical handling

equipment was still lacking and the crews were still without permanent living quarters.22

The maintenance of toxics in storage involved a number of special problems arising from the nature of the materials. Mustard, which constituted by weight well over half of all the toxics produced by the CWS, required particular attention. In the form produced during most of the wartime period (the so-called Levinstein H) it contained about 30 percent of more or less unstable impurities which introduced some complicating factors when it was left in storage for any length of time. It evolved gases at a rate which sometimes built up dangerous amounts of pressure within the containers. It deposited tarry sludges which could not be drained out. Handlers had to learn techniques for testing pressures in containers, venting them when necessary, and cleaning them after they were drained. The possibility of leakage was always present, and with it the likelihood that other containers near the leaking one would become contaminated. Midwest Depot found it necessary at one time to segregate a large number of suspect toxic-filled containers in a “sick bay” to keep them from contaminating the rest of the toxic yard when, as sometimes happened, a combination of corrosion and high pressure produced a sudden spray of mustard through a leak.23

When toxics were stored in 55-gallon drums instead of ton containers, as necessity or convenience sometimes required, problems of corrosion and leakage multiplied. If the drums were shipped and stored standing on end they were likely to trap rain water on top and rust. If they were placed on their sides some of the bungs at the ends were likely to leak. Eventually CWS decided that in depots, at least, it was better to leave the drums on their sides and keep inspecting them for leaks, than to risk accelerated corrosion through rusting.24

In view of the undependability of containers and the highly dangerous character of toxic agents, it was very important that shipments of toxics be accompanied by guard details trained to handle such materials and to recognize and deal with potential sources of trouble. When large-scale shipments of toxics in and out of depots began in 1942, trained servicemen were picked up wherever they were available to act as guards and

Toxic gas yards, Midwest Chemical Warfare Depot, Pine Bluff Arsenal, Arkansas.

handlers. The first trainload of mustard from Huntsville Arsenal to the toxic yard at Midwest Depot, for example, was convoyed by the first 7 men the depot had sent to Edgewood for training as toxic gas handlers; they were simply detailed to stop off at Huntsville on their way back from Edgewood in order to accompany the train.25 In other cases the installation originating shipment provided a guard detail from its own military personnel to act as convoy.26 It seemed advisable as time went on to provide a centrally available and uniformly trained detachment to handle all convoy duties incident to the shipment of toxics and chemical munitions. Accordingly, in January 1943, on the recommendation of OC CWS, the Services of Supply directed the Chemical Warfare Service training center at Camp Sibert, Ala., to set up and train a detachment of 20 officers and 100 enlisted men for service as a guard and security unit for the shipment of toxics.27

The unit was duly brought into being at Camp Sibert as a section of the RTC Specialist Schools. Its enlisted men came from the 1st and 2nd

Regiments of the RTC, and the officers were attached from the CW Officers’ Replacement Pool. On 1 February 1944 the unit was transferred to Headquarters Detachment I, Chemical Warfare Center at Edgewood, where it remained for the rest of the war. Its strength rose to a wartime peak of about three hundred and fifty officers and enlisted men.28 The unit carried on a three-week training program for all men assigned to it.

Within the zone of the interior the principal job performed by the guard and security unit was to escort rail shipments of toxics and toxic filled munitions to and from depots, arsenals, and ports of embarkation. A guard detail, headed by a junior officer, took custody of each shipment at its point of departure, accompanied it via railroad caboose throughout its journey, maintained a continual alert for emergencies, checked the cars for evidence of contamination at each stop, and made detailed inspection of the condition of the shipment during major stopovers. All leaks found in containers or casings were repaired. Cars found to be contaminated through extensive leakages of toxics were promptly sidelined and guarded until they could be decontaminated or the contents reloaded.29

If the shipment was bound overseas, the guard detail went overseas with it. It supervised loading on shipboard and also guarded the materiel. While at sea it kept a daily check of the ship’s ventilating system to make sure that no toxic vapors were contaminating the air. The crew was equipped with gas masks and given instruction by the detail in gas mask drill, first aid, and decontamination. After the destination was reached, the cargo was inspected again before being unloaded.30

Storage of Other CWS Items

Incendiary Bombs

The transfer to the Chemical Warfare Service of responsibility for the incendiary bomb program in the late summer of 1941 brought with it the need for magazine operations on a scale hitherto reserved for Ordnance, Storage requirements for items capable of explosive or incendiary behavior—both of which could be expected from incendiary bombs in case of accidents—followed a fairly strict pattern based largely on Ordnance

experience with ammunition storage. From 1928 onward the typical Ordnance high-caliber ammunition magazine had been built in the form of what was called an igloo. Igloos, in Army terminology, were low concrete buildings of semi-cylindrical shape, covered with sod. The arching walls were designed to direct the force of an explosion upward.31 Several small igloos were already in existence at Edgewood Arsenal, including some half-dozen built as part of the emergency period expansion program in 1940-41.

When the incendiary bomb program materialized, the CWS at once began work on plans for igloo construction at the proposed new depots on a scale large enough to provide permanent storage for 40,000,000 four-pound bombs.32 A type of igloo used by Ordnance for the storage of smokeless powder became the prototype for the CWS building program. This igloo had exterior dimensions approximating 29 feet by 82 feet—twice the length of the igloos recently erected at Edgewood. According to estimates, it would store about 58,500 four-pound incendiary bombs in its 2,200 square feet of interior space. A 300-foot interval between igloos was considered standard.33

The new depots provided sites for hundreds of igloos. Two hundred and twenty went up at Midwest Depot, and some three hundred and fifty at Gulf Depot. Deseret accommodated 140 igloos. The activation of Northeast Depot in 1944 brought an additional fifty-eight igloos into the CWS storage program, so that altogether nearly eight hundred of these specialized magazines were brought into use by the CWS after completion of its original expansion plan at Edgewood.34

By the summer of 1942 the first shipments of incendiary bomb clusters were beginning to fill the new facilities. As the carloads arrived, the 100-pound clusters were manhandled into the igloos from the railroad docks via trucks and roller conveyors arid stacked inside by hand, as many as twelve to a stack. This procedure, time consuming and laborious as it was, remained without much change for more than a year until the use of fork-lift trucks and pallets became general. A number of devices had by then been improvised for handling 100-pound and 500-pound clusters.

Crane operated booms and jigs lifted a truckload of clusters at a single operation, the standard load being seven 500-pound M17 clusters.35

The igloo capacity of the CWS, despite its great expansion, was not enough to guarantee interior storage of bombs at all times. Frequently depots and arsenals found themselves obliged to resort to open storage. Furthermore, when supplies were moving quickly in and out of the depot, open storage was often the more economical of time and labor. Storage out of doors was not harmful if the necessary precautions were taken. The packaged clusters had to be placed on platforms allowing at least a few inches of air to circulate between them and the ground. Reasonable limits had to be observed in the size of the stacks, their nearness to each other, and the total number of clusters kept in one area.36 Of particular importance was the necessity for providing the stacked clusters with some protection from the elements. At first, it was customary to cover the stacks with tarpaulins. It was not sufficient, however, simply to drape the weatherproofing on the stacks. While the packaged clusters were not very susceptible to damage from occasional incidental sprinkling, they were, on the other hand, vulnerable to corrosion and rotting if the tarpaulins covered them so closely as to prevent the free passage of air.37 Some storage areas arranged stacks with a narrow row of boxes on top to provide a sort of ridgepole for the tarpaulin covering. Others used supporting frames of light timber. Midwest Depot, which found tarpaulins difficult to procure in quantity, hard to handle, and quick to deteriorate, devised a new system. The light timber “A” frames which had been constructed to support the tarpaulins were discarded. In their place 20 foot by 20 foot frames were built, covered with tarpaper, and placed on top of the stacks like so much shed roofing.38 This proved to be adequate protection and not too burdensome to handle, provided cranes were available.

Bleach

The packaging and storage of bleaching powder was hardly as big a responsibility as the handling of incendiaries, but it proved to be one of

the most troublesome episodes in the wartime storage experience of the CWS. Bleaching powder (calcium hypochlorite), in addition to its powerful oxidizing action, liberates free chlorine. Since it was a cheap and abundant commercial item it was an obvious choice for chemical decontamination of the persistent toxic agents, which decomposed into relatively harmless compounds when chlorinated. On the basis of World War I experience, the CWS considered bleaching powder its standard general-purpose decontaminating agent, and once the nation was at war again it prepared to lay in large supplies.

No sooner had the depots begun to fill their warehouses with drums of bleaching powder than difficulties began to appear. The bleach was not high-test hypochlorite, a product of relative purity and stability, but a lower commercial grade of variable composition and inconvenient characteristics. It came packed in large steel drums, covered, but not tightly sealed. The powder took up moisture from the air and began evolving chlorine, sometimes at a rate sufficient to blow the tops off the drums. At the same time it was slowly but steadily corroding its containers, not only from the inside, but, thanks to careless packing and the resultant dusting of bleach on the drum exteriors, from the outside as well. This double process of decomposition and corrosion was accompanied by a parallel decline in the potency of the bleach itself. By the time the country entered its second year of war much of the bleaching powder held in storage by the CWS had become worthless.39

The situation had not failed to arouse concern. The CWS sought the advice of its suppliers at a conference at Niagara Falls in November, 1942. But the manufacturers could not offer much comfort. They themselves had never found an economical container for bleach more effective than the galvanized steel drum. Furthermore, it had never been customary in industry to keep bleaching powder in storage for more than a few months. After this meeting Lt. Col. Ludlow King, Chief of Inspection Branch, Industrial Division, OC CWS, was detailed to study possible substitute containers and came to the conclusion that no available metal drum could be regarded as offering guaranteed satisfaction for the long-term storage of ordinary American bleach. The CWS then adopted the practice of packaging bleach for storage in steel drums which had been provided with heavy coats of baked lacquer, inside and out. Containers of this sort

appeared to be the best available for the purpose, though they, too, were not immune from corrosion.40

In addition to improving the containers, CWS technicians could attack the problem of storing bleach successfully through improving the bleach. In early 1943 there seemed no immediate likelihood of procuring high-test hypochlorite from American sources for CWS use.41 Fortunately another source of relatively stable bleaching powder was at hand. The British had been producing a surplus of bleach of a quality well above that of the American commercial grade, and from the fall of 1942 substantial quantities of this product were made available to the CWS through reverse lend-lease. Between September 1942 and March 1943 a total of nearly 16,000 tons of British bleach entered the CWS supply system, twice the amount obtained from American manufacturers in the same period.42 But this windfall was not without its disadvantages. The British bleach arrived packed in drums which did not meet demonstrated storage requirements. The CWS promptly repackaged it in 100-pound lacquered steel drums. The job of repackaging was one of the most laborious experienced by the depots. The bleaching powder, as just noted, was corrosive and the chlorine gas it evolved was both suffocating and poisonous. The crews engaged in shoveling the bleach from container to container were obliged to wear full protective equipment, including gas masks and special clothing. They were greatly relieved when the task was done.43

Packing and Packaging

The problems encountered in keeping bleach in storage constituted only one instance of a general deficiency. Items had entered the distribution system before techniques had been developed to keep them in storage safely or see them on their way with reasonable assurance of safe arrival. One of the obvious responsibilities of a distribution system is to get materiel to its destination intact. To a large degree the successful fulfillment of this responsibility depends on the protection provided by the packing methods utilized. This fact is especially true when the system

must supply expeditionary forces through all the hazards of wartime communications and in virtually all the climates of the world. The demands of the war on the CWS packaging techniques revealed shortcomings that had escaped notice during the peacetime years and the prewar build-up. It took many months for CWS packing doctrine and practice to catch up to the requirements of global war.44

For the most part, CWS packing and packaging had met ordinary peacetime standards. Packaging specifications were often simply references to ICC requirements for shippers using common carriers. Many items were never considered liable to overseas shipment and were packed in a manner suitable to the needs of domestic railroad requirements only, while even material bound overseas was given only the care and safeguards of normal peacetime ports and shipping. In some cases packing specifications which in themselves might have been basically sound were waived for shipments designated “emergency.” The shortcomings of the existing packaging practices became generally apparent after the first major overseas landing operation by American forces in French North Africa late in 1942. Under the pressure of rough and hasty handling, improvised storage, over-the-beach landing, salt water corrosion, emergency unpacking, and the like, all factors inevitably associated with supply in an active theater of operations, many CWS packing and packaging methods failed to meet the demands made of them. This was true of Army packing in general, and theater complaints became the subject of top level Army concern.45

CWS officials, studying the reports of packaging failures and corrosion overseas, found six major factors responsible for the trouble: (1) inadequate packing and packaging design particularly in the selection of packing materials; (2) poor workmanship by inexperienced labor; (3) insufficient emphasis by inspectors on adherence to packaging standards; (4) poorly designed blocking and bracing, in view of the rough handling to be expected; (5) unanticipated outdoor storage; (6) unanticipated climatic conditions.46 It was evident that immediate action was needed to redesign inadequate packages and packing to meet the actual stresses encountered.

A packaging unit was created within the Technical Division early in 1943 and assigned specialized personnel and laboratory space at Edgewood Arsenal. This unit, subsequently raised to branch status, began at once to develop new designs and specifications where the need existed.47 The basic problems dealt generally with increasing the strength of packages, cutting size and weight down as far as practicable, denying access to water or water vapor, inhibiting corrosion, and preventing mildew. Such things as materials shortages had to be kept in mind as well as the matter of ease and speed of packaging. The variety of overseas destinations multiplied the difficulties. The Pacific theaters, though the first impact of their requirements seems to have been less than that of the North African landings, presented some of the most complex problems. Supplies there were often landed on small beaches, without mechanical equipment or trained labor, and, in the early days especially, under the fire of enemy snipers or aircraft. Sometimes materiel was simply floated ashore. Once landed, it had to be hauled through jungles, stored during tropical rainstorms, and protected somehow from the corrosive humidity.48

The point of departure for packaging development in the CWS, as in the other branches of the Army, was War Department Specification 100-14A, which prescribed general requirements and indicated standard methods of crating and boxing. Within these limits, whenever possible, and outside them when necessary, the CWS packaging laboratory developed specific packaging requirements for all the items in the CWS supply system.

Crates were used for packing a few comparatively bulky CWS items, such as smoke tanks and smoke generators. These had to be specially designed in each case, with particular care to make sure that hard surfaced points on the item or the bracing were not so placed as to abrade the waterproof paper liner. Corrosion prevention for hardware was accomplished by cleaning all ferrous surfaces and coating them with grease or oil.

For the greater number of CWS items, boxes of one sort or another were devised and specified. In some cases the specifications were changed over and over again in the attempt to attain the best possible protection in the face of a variety of hazards. The 500-pound aimable cluster, M19, an adapter holding thirty-eight M69 incendiary bombs, was one such

example. The bombs had to be kept moistureproof, particularly since their fuzes contained black powder and would become inactivated if subjected to high humidity. There was no point in using vaporproof film covering with silica-gel dehydrator, as prescribed for moistureproof packing in some other services, because there was almost no silica-gel available to the CWS, nor could handlers conveniently or economically wrap the awkwardly shaped cluster in film without puncturing it. The first solution arrived at was a metal-sheathed, hermetically sealed plywood box. This proved satisfactory on an experimental basis, but attempts to secure rapid quantity production failed. Then a similar box made entirely of steel was substituted; it was unduly heavy but otherwise almost as satisfactory as the first. Again, production fell, in this case as a result of failure to observe the close tolerances needed to assure a vaporproof seal. By this time, however, a double steel drum pack (two steel drums fitted end to end over the cluster and sealed with a clamp and a sponge rubber gasket) had been worked out and proved to meet the basic requirements. This pack was ultimately adopted as standard. Subsequent difficulties ensued when stocks of fully dried wood for interior bracing ran out. To avoid raising the humidity inside the pack, a new bracing system was worked out incorporating moisture laden wood. This problem was solved only as the war ended.49

While troubles of this sort kept the packaging laboratory busy throughout the war, the worst of the lag in packaging development was overcome in the course of 1943. Before the year was out the packaging development chief was able to venture the opinion that most of the big changes had already been made.50 But many routine packaging and packing designs remained to be worked out and revised during the remaining two years of war. Generally speaking, the problem of safely containing bulk quantities of highly reactive chemicals under wartime conditions was never solved. There was no certainty that existing containers for toxics would not burst or corrode, and the ever-present possibility of “leakers” in lots of toxic-filled drums or munitions imposed a perpetual state of alert on depot and transportation personnel. Even so familiar a commercial item as bleaching powder developed problems of corrosion in storage, mentioned earlier in this chapter, which were ameliorated but

Drums of bleaching powder stacked at a depot in England, August 1943.

never completely solved before hostilities ceased, remaining to challenge the ingenuity of CWS technicians in the years that followed.

Distribution

The CWS distribution system functioned in general along lines laid down by the ASF. Its depots were allocated responsibilities by OC CWS in such a way as to conform with Army requirements for regional decentralization. For the most part its filler depots were located well back of the seaboard—in Utah, Arkansas, and northern Alabama, for example—a circumstance which tended to reduce congestion at and near the ports, as far as CWS materiel was concerned. The one major exception was Eastern Depot at Edgewood, Md., the original center of the distribution system; but the policy of moving storage functions back from the crowded coast was applied at Eastern also, when first the major part of its general supplies responsibility and then a substantial share of its ammunition storage functions were shifted inland to New Cumberland and Northeast Depots respectively. The CWS, which for years before the war had a minimal distribution load centering on a single depot consisting mostly of gas masks, succeeded in getting a nationwide depot system into operation,

meeting modern standards of depot management and materials handling, shipping large quantities of ammunition and toxics without serious incident, and keeping supplies moving to overseas theaters, Lend-Lease nations, and the training centers at home.

Supplying the Corps Areas

During the emergency period before the entry of the United States into the war, the CWS, like the other supply services, supplied equipment to zone of interior installations and units through the several Corps Area commanders.51 As in the period before the emergency each Corps Area Headquarters received requisitions from posts under its jurisdiction, edited them, and forwarded them to the appropriate supply service. CWS materiel was supplied by OC CWS through the depot at Edgewood. The first expansion of the peacetime distribution system centered in Edgewood Arsenal came early in 1941 when the Boston Chemical Warfare Procurement District was designated as the source of supply for training masks for posts in the First, Second, Third, and Ninth Corps Areas, and the Chicago District became the source for the remaining areas.52 (At this period training masks for the suddenly expanded Army were the chief distribution responsibility of the CWS.) The new CWS depots and the chemical sections of the ASF depots did not begin to figure in the active distribution system until the end of the emergency period.

A few weeks after Pearl Harbor the War Department moved to expedite the distribution process by ending the role of the Corps Area Headquarters as a middleman between posts and depots. Henceforth, depots were to receive consolidated requisitions directly from post supply officers and make shipment accordingly.53 By this time the chemical sections of the general depots were ready to bear their share of the distribution load. Accordingly, a new regional supply system was set up by OC CWS, giving Edgewood Depot responsibility for serving Corps Areas I-III, the chemical section of Atlanta General Depot responsibility for Corps Area IV, the chemical section of Memphis General Depot responsibility for Corps Areas V-VII, the chemical section of San Antonio General Depot responsibility for Corps Area VIII, and the chemical section of

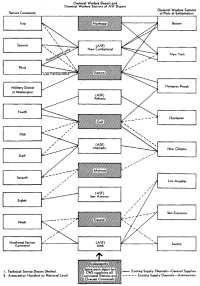

Utah General Depot responsibility for Corps Area IX. These chemicals supply points were required to maintain computations of unit allowances and records of current status of CWS materiel authorized for organizations in the Corps Area served.54 This regional distribution system for general supplies was the first and basic step in CWS participation in the War Department’s continuing campaign to decentralize supply functions and maintain balance in movement of materiel. World War I experience in the clogging of supply lines at the Ports of Embarkation provided a warning of the vital necessity of balancing supply movements with supply facilities, an example reinforced by the threat of congestion at east coast ports in 1942. The CWS regional distribution plan described above was limited to general supplies, such as protective equipment, and still left Edgewood with a disproportionately large share of responsibility. The system approached completion before the year was out, though, as one by one the new CWS branch depots were activated. Each of these became responsible not only for general supplies but also for the distribution of ammunition and toxics on a regional basis. Thus Gulf Depot dealt with the Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Corps Areas (or Service Commands, as they were subsequently designated), Midwest with the Seventh and Eighth, and Deseret with the Ninth. The remaining Service Commands, the First, Second, and Third, continued to draw on Eastern Depot at Edgewood for the chemical ammunition. Eastern’s supply load was further reduced on 30 April 1943 when its responsibility for the distribution of general supplies was cut back to that area of the Third Service Command south of Pennsylvania. The First and Second Service Commands, plus Pennsylvania, were served thereafter by an additional chemical section, that of the New Cumberland ASF Depot. Again in 1944 Eastern’s storage and shipping load was divided when the activation of Northeast Depot (on a site originally developed by the Ordnance Department) provided an additional East Coast depot for chemical ammunition, a facility particularly helpful in providing extra back-up storage for the New York Port of Embarkation. (See Chart 2 for CWS distribution network.)

The regional allocation of responsibilities among the facilities in the CWS depot system served to meet ASF requirements for decentralized supply. The designation of depots by function—filler, reserve, distribution, or key—was also accomplished in accordance with ASF standards, though

Chart 2: Schematic diagram, chemical warfare supply, as of 6 December 1944

Source: Baltimore-Liaison Office, Storage Branch, Supply Division, OC CWS, Dec. 1944.

in an organization as small as the CWS, this required the assignment of multiple missions to most of the installations. Distribution depots were those which supplied materiel to posts, camps, and stations within a designated region. The chemical sections of ASF depots and the CWS branch depots fulfilled this function for general supplies and ammunition respectively. Reserve depots stored additional stocks for the replenishment of the distribution depots; this function was also included in the missions of all CWS storage installations, with a range of materiel, broad or limited as the case might be, specified in each instance. Filler depots provided a storage service for the Ports of Embarkation by filling Port requisitions out of their stocks, thus reducing the likelihood of an unmanageable accumulation of goods on the seaboards. Each CWS installation had a mission assignment as a filler depot for one or more ports. Key depots were those whiCh stocked special items whose distribution could be more usefully accomplished from centralized control points than through the standard regional setup. The only CWS depot with this type of mission was Indianapolis, which controlled the distribution of all CWS spare parts.

An additional measure of specialization was carried out by the major CWS branch depots. Eastern, Gulf, and Midwest Depots shared locations with three of the four CWS arsenals. They took advantage of this circumstance to act whenever practicable as primary destinations for the products of their respective arsenals regardless of the ultimate destination envisaged. This tended to reduce crosshauling and backhauling by keeping the materiel out of any actual transit until it was needed. In order to perform the same service for Rocky Mountain Arsenal, which had no CWS depot at hand, Deseret established a storage area under its own jurisdiction adjacent to the arsenal.

Stock Control

A major purpose of the decentralizing of depot functions was, as has been stated, the avoidance as far as possible of the inevitable tendency to choke the lines of distribution with an oversupply of goods, a condition particularly acute at the ports, where the lines of distribution converged on a few overcrowded centers. A rigorous system of stock control, based on limitation of station stock levels and the provision of careful controls on the rate at which materiel moved to the ports was the obvious corollary of the new depot system. In 1942 the Control Division, ASF, made a survey of stock control practices in the CWS. The survey disclosed that a records system fot approximately 1,000 items, including components,

was maintained. Of this number only thirty-eight were fast moving items, and on these a daily report was received from each depot and port of embarkation. This report which listed on-hand figures, was used as a basis for filling requisitions and setting up credits. On another sixty items weekly reports were made to the Office of the Chief, and on still another sixty-five, monthly reports were made. The remaining chemical warfare items were reported periodically. A record of all chemical warfare items in CW depots was maintained on hand-posted sheets in the OC CWS, as well as on a prescribed hand-posted form in the depots. The survey found that the system was workable only because there were few items and because the bulk moved slowly.55

Early in 1943 the Assistant Chief of Staff, ASF, for Operations, Maj. Gen. LeRoy Lutes, requested the chiefs of the various technical services to submit recommendations for implementing a stock control system.56 During the next two months the ASF worked up a tentative stock control manual which was issued on 3 May 1943.57 This manual was to be later revised several times on the basis of actual experience.58 When issuing the tentative stock control manual, Headquarters, ASF, at the same time directed the technical services to set up stock control, storage, and maintenance units in their headquarters.59

The tentative stock control manual stipulated that the new system was to go into effect by 1 June 1943. It provided that each post, camp, and station as of that date would have an established supply level based on the actual needs of troop units. This level in most cases was first established as a 90-day level, a figure which fluctuated from time to time. All stocks above the established level were to be declared excess and returned to the depots. Stock levels were also established for the depots. Much cooperation was necessary among the commanding officers of the headquarters of the technical services, the headquarters of the service commands, the depots, and the post supply officers in order to fix accurate stock levels, but this objective was gradually accomplished.60

An important feature of the new stock control system was the scheduled requisitioning of supplies. Troop units sent their requisitions to the post supply officer who in turn presented his requisitions to the depot on a standard form and according to a fixed schedule. This innovation helped to prevent alternate periods of peak and slack activity in the depots. Station supply officers kept the chiefs of the technical services informed on the stock status of their particular stations and in that way the volume of stock to be maintained at the depots was gauged.61

Though the stock control system led to marked improvement in the issue of items, a serious deficiency in the distribution system still remained. That deficiency was failure to control the flow of materials from production lines to the depots. “That,” said General Lutes after the close of World War II, “is an excellent illustration of one of the most important lessons about Army supply; that is, that the supply process is an individual entity and cannot be broken down into uncoordinated phases such as production, stock control, and distribution.”62 With the advent of the supply control system in the Army in the spring of 1944 came a concerted effort to coordinate the various phases of the supply process.63

Lend-Lease

While the Chemical Warfare Service’s program for supplying U.S. forces was moving into high gear, a parallel supply effort was already under way. The inclusion of the defense needs of friendly nations among the supply responsibilities of the Army antedated Pearl Harbor by more than a year and was given statutory authority by the Lend-Lease Act of March 1941. That portion of the War Department’s lend-lease commitments represented by chemicals and chemical warfare supplies fell to the CWS to fulfill. The task of receiving and satisfying the demands of U.S. allies for such materiel was supervised by the Navy and International Aid Branch of OC CWS, but the main burden fell upon the regular staff and operating organizations in CWS.64 The official beginning of CWS participation in lend-lease dated from shortly after the Lend-Lease Act was passed,

but CWS concern with the war requirements of the British Empire went back somewhat farther than that. Though it was not called upon for foreign aid materiel in 1940, as was the Ordnance Department,65 the CWS at this time did have very close liaison with the British Purchasing Commission, particularly on the procurement of chemicals. The official in charge of the procurement of chemicals on the British Purchasing Commission (BPC) was an American CWS reserve officer in the New York Chemical Warfare Procurement District, Lt. Col. W. Hepburn Chamberlain. Colonel Chamberlain’s acquaintance with British requirements for chemicals enabled him to gauge the extent of the demands which would be made on American chemical resources under similar conditions, and the more he studied the matter the more he became convinced that the United States estimates were much too low. In 1940 Chamberlain left the BPC to join the Office of Production Management, where he was instrumental in impressing upon the leaders of the American chemical industry, with whom he was well acquainted, the need for expansion to meet wartime needs. In processing orders for the British (and that included the entire British Empire and its allies) he negotiated with the leaders of the American chemical industry on the expansion of existing plants or the building of new ones. These plants were a distinct asset to the nation once it got into the war.66 Colonel Chamberlain was called to active duty as an Army colonel shortly after Pearl Harbor and became the officer in charge of lend-lease operations in the CWS throughout the greater part of the war.

The first direct impact of the Lend-Lease Act on the CWS came in April 1941, when the Secretary of War directed the transfer of 200,000 service masks, complete with spare canisters and repair kits, to Great Britain, for ultimate transshipment to Yugoslavia. The Chicago Procurement District’s storage warehouse filled the order.67 During the same month the first British requisitions for phosgene arrived.68 In the course of the next few months the British requisitioned a number of defensive

chemical warfare items and chemicals.69 More significant in terms of the future were the preparations under way late in 1941 for the first transfers to the British of incendiary bombs, destined to be the largest single item of lend-lease materiel handled by the CWS.70 As early as October 1941, the Lend-Lease Administrator allocated $10,000,000 to the Army for construction of an incendiary bomb plant at Pine Bluff.71 Planners thus fully realized that during the following year the major effort in the early production of incendiary bombs by the CWS would be for British requisitions, despite the fact that the United States entered the war in December. Though the CWS, in the absence of any directive to the contrary from higher authority, filled American requisitions for magnesium incendiaries before authorizing manufacture for British requirements, roughly two-thirds of the production of magnesium incendiaries (M50) went to fill British requirements. This two to one ratio was observed faithfully enough to give the WPB the impression that it had been based on a formal Anglo-American agreement.72 The first lend-lease shipment of incendiary bombs was sent to Great Britain early in 1942. Before the war was over, a total of over 66,000,000 of the 4-pound magnesium bombs, M50, valued at more than $172,000,000 had been shipped to England, as well as 15,000 1000-pound aimable clusters, and a few M69 oil (napalm) incendiaries.73

Of the chemical agents that the CWS procured for the British, by far the most important was white phosphorus. Shortly after the United States entered the war the British were looking forward to an ultimate supply of a thousand tons of white phosphorus per month from the CWS. The total they actually received during the course of the war exceeded 16,000 tons.74 The chief obstacle was not so much the production of the agent itself as the difficulty of getting it shipped. A critical shortage of

containers early in 1943 produced a proposal for a 70 percent cut in British allocations of white phosphorus. This evoked an immediate protest from the British supply mission. It called attention to the fact that the Combined Raw Materials Board had suggested that vital shipping space would be saved if the United Kingdom stopped importing American phosphate rock to make its own phosphorus and depended instead on getting the finished product from America. One of the two British phosphorus plants had already been closed down in consequence, and closure of the other was imminent. The shortage of shipping space being more serious than the shortage of steel for containers, the British view prevailed, and most of the cut in the white phosphorus allocation was restored.75

Of the other standard chemical agents, substantial quantities of phosgene and FM (titanium tetrachloride, used as a filling for smoke shells) went to Great Britain under lend-lease action. But the shipments of industrial chemicals which the CWS procured for British needs were often of greater importance than these. For example, a total of 34,000 tons of ethylene glycol, an engine coolant and antifreeze, was shipped to the United Kingdom during the war. Two special purpose rubber substitutes, neoprene and polyvinyl chloride, accounted for shipments of 7,500 tons and 8,500 tons respectively. It would take the enumeration of over fifty other chemicals to complete the list. Also of importance in the British lend-lease program were CWS-supplied smoke grenades, HC smoke mixture, and a number of items of protective equipment.76

The principal customer for CWS lend-lease shipment, after Great Britain, was the U.S.S.R. But unlike the British program, which was dominated by the mass production and shipment of incendiary bombs, the Russian requisitions were mainly for industrial chemicals. Chief among these, in terms of tonnage shipped, were methanol (28,000 tons), caustic soda (22,500 tons), phenol (18,000 tons), and ethylene glycol (13,000 tons). The only munitions which the CWS shipped to the U.S.S.R. in quantity were smoke pots. The Russians received about 1,300,000 M1 smoke pots (HC), and 130,000 floating smoke pots.77 The heavy tonnage of caustic soda reflects in part the U.S.S.R.’s strong demand for this chemical, for use in refining petroleum. The requisition came after the Germans had retreated from the Caucasus at the start of 1943 and the

Russian refineries had begun to receive once again the products of the Caucasian oil fields. After an all-out effort by CWS officials to locate every available source and organize immediate delivery, fifty-six carloads of caustic soda were assembled in Chicago and sent on their way. Somewhat later in the war, procurement of caustic soda was transferred from the War Department to the Treasury Department. Other chemicals sent to the U.S.S.R. by the CWS went into the manufacture of such military necessities as smokeless powder, plastics, explosives, and high octane gasoline.78

shipping problems present to some extent in lend-lease distribution generally tended to become more acute in the case of the Russian supply program. Chief of these was the problem of coordinating shipments with vessels. Before 1942 was out, large stocks of some chemicals were being held in warehouses and War Department holding and reconsignment points because ships were not available to take them overseas.79 It became evident eventually that the Russians were putting off acceptance of requisitioned chemicals for shipment whenever they had cargoes of greater concern to them ready to fill the available ships. In some instances these delayed chemicals were finally diverted to American war production, as in the case of 900 tons of unused sodium bromide.80 For the most part, the CWS had to meet the storage problem as best it could. Special care had to be given to keeping containers in good condition during periods of unscheduled storage. On one occasion an inspection team from the Chemical Commodity Division, OC CWS, finding it necessary to perform an emergency repaint job on large lots of chemical containers held at Cheyenne, Wyo., had to call on Quartermaster troops for help in order to prevent further large-scale deterioration.81

Canada, Australia, French North Africa, China, and Brazil also received substantial amounts of CWS-procured materiel, though Canadian shipments were purchases, rather than lend-lease. The CWS sent to Canada some 3,500 tons of mustard gas and smaller amounts of lewisite, phosgene, and smoke mixture (FS), together with 400 tons of whetlerite and

several hundred smoke generators.82 Australia, preparing for the possibility of invasion after Pearl Harbor, felt it advisable to stockpile 4,000,000 civilian gas masks. As only a quarter of these could be produced locally, over 3,000,000 were requisitioned and obtained from the United States.83 The CWS participated in the task of rearming the French by shipping to North Africa all the chemical warfare items for initial equipment and maintenance for the eleven French divisions being outfitted there in 1943. Service gas masks and dust respirators were the major items in this program.84 The CWS also contributed its share to the limited flow of American supplies to China, via the China-Burma-India Theater. For the most part the CWS materiel sent to China consisted of weapons and ammunition, some of it for use in conjunction with General Stilwell’s campaigns in Burma. Among the major items were 327 4.2-inch mortars, 1,470 portable flame throwers (for which the demand was increasing in the CBI Theater), over 500,000 mortar shells, and over a quarter of a million smoke grenades. Half a million outlet valve assemblies went overseas to keep the Chinese gas mask factories going.85 Brazil received as lend-lease materiel the chemical warfare equipment needed to outfit the troops it sent to Europe early in 1944. Over and above these items, the CWS sent about 500 tons of bleaching powder to Brazil.86 Small amounts of CWS materiel went as lend-lease to more than a dozen other countries. The final CWS report listed a total of 312 separate items procured for lend-lease.87

Supplying the Ports of Embarkation

A basic responsibility of zone of interior distribution was supplying the ports of embarkation, the Army commands which, under the general authority of the Chief of Transportation, supervised the transfer of men and materiel overseas. Within each of these commands a chemical officer served as adviser to the commanding general on technical matters in his

field while at the same time heading an organization performing a variety of CWS functions. The port chemical officer had a training mission, giving refresher training in protection against toxic gas to station personnel and troops bound overseas as well as decontamination training to help avoid accidents in handling toxic cargoes. He had an inspection mission, involving the checking of CWS cargoes for serviceability, safety, and proper loading and stowing. Finally he had a supply mission which required him to act as CWS supply officer at his post, forwarding requisitions from the theaters, filling shortages for units in transit, receiving, storing, and preparing for export CWS materiel received, and maintaining stock control records accordingly.88 This supply function enabled the post chemical officers to serve as the link between the CWS distribution system and the ports, as represented by the commanding generals of the ports of embarkation and their staff sections. For the chemical officers were responsible in the first instance to the port commanders, rather than to the Chief of the CWS, and their activities in the field of overseas supply were carried on under the immediate direction of the ports’ overseas supply officers.89 Indeed, as far as the overseas theaters were concerned, CWS supply liaison was maintained through the overseas supply divisions of the ports, the agencies which first edited their requisitions, and hence only indirectly with the port chemical officers.90

Chemical sections were first activated in the ports of embarkation in the latter part of the emergency period. A chemical section existed in the San Francisco General Depot (which acted as supply agency for the San Francisco Port before Pearl Harbor) as early as October 1940, but the first Port Chemical Warfare Sections, properly so called, were those activated at the New York and New Orleans Ports of Embarkation in August 1941. Within three months after Pearl Harbor, CWS sections were in operation at the Seattle, Charleston, and Boston Ports of Embarkation, as well as at San Francisco, where the supply functions were shifted to the Port of Embarkation in December 1941. The Chemical Warfare Section of the Hampton Roads Port of Embarkation came into being in August 1942, and that month also saw the beginning of CWS supply functions at the Los Angeles subport, an installation which attained independent POE status in the fall of 1943. The volume of CWS lend-lease cargo passing

through the Portland, Ore., subport necessitated the appointment of a port chemical officer there in September 1942. A final addition to the number of port chemical officers was made in December 1943 when a CWS officer was assigned to the Baltimore Cargo Port of Embarkation.91

As in the case of the service commands, the ports of embarkation operated under a regional allocation of CWS supply facilities. According to the pattern that ultimately emerged, the west coast ports dealt with Deseret and Utah Depots for CWS ammunition and general supplies respectively. Midwest and Memphis Depots served New Orleans Port of Embarkation similarly, with additional supplies shipped from Gulf Depot. The east coast ports were served by Eastern, Gulf, and Northeast CWS Depots and the ASF Depots at New Cumberland and Atlanta. The depots dealt with port requisitions directly and on a priority basis, advising OC CWS of shipments made. The CWS made periodic efforts to speed up the processing of requisitions which could not be filled at once from stocks on hand. In 1944, the chiefs office received permission from Headquarters, ASF, to short-cut prescribed procedures by acting itself to teletype an order to a second depot to fill shortages in a requisition which the original depot could not complete. This system served to make OC CWS a clearinghouse for the speedier dispatch of unfilled extracts of requisition to known sources of supply and ended the necessity of having depots send them haphazardly from one to another until supply could be made. It also eliminated the additional delay involved in the earlier practice of routing the final shipping order back to the original depot before shipment was made to the ultimate supplier.92

By and large, the supply function of the chemical sections of the ports was an extension of the work of the depots. The tasks of storing, maintaining, shipping, and receiving were similar, as were many of the problems encountered. The sections had to devote time to checking the adequacy of packing and marking, replacing corroded containers, and maintaining surveillance over toxics. As the system of regional filler depots was elaborated by the ASF and the supply services, the ports of embarkation were enabled to close out a substantial share of their storage operations, but some necessarily remained to be performed on the spot.

The scale of operations varied considerably from port to port. The San Francisco Port of Embarkation, bearing primary responsibility for supply of the Pacific theaters, processed a rising flood of CWS equipment and

materiel, the monthly total reaching a peak of 63,287 measurement tons in July 1945, just as the war was being won. Incendiary bombs, grenades, napalm, mortar shells, toxics, and gas masks dominated the shipments.93 The New York Port of Embarkation, which received the requisitions of the European and Mediterranean theaters, shipped its peak load of CWS materiel in April 1944, just before the Normandy landings, when 48,109 measurement tons were processed.94 The other ports never dealt with burdens of this magnitude, but many of them had special needs to satisfy. The New Orleans Port of Embarkation, for example, shipped the variegated and often highly dangerous supplies needed for support of the San Jose research project in the Canal Zone. The Seattle Port of Embarkation experienced an emergency period during the Japanese invasion of the Aleutians in mid-1942, when men and supplies had to be gotten to bases in Alaska as rapidly as possible. The danger of submarine attacks in the early days of the war was such that some ports had to handle shipments diverted from more hazardous routes; the Los Angeles Port of Embarkation more than once had to ship organizational equipment to the China-Burma-India Theater for units whose personnel were shipping out by way of Charleston. This responsibility involved cross-country liaison through a representative of the unit concerned.

Generally speaking, the pace of the American war effort in the zone of interior tended to slacken in the summer of 1945, when only the conquest of Japan remained to be achieved. But the CWS experienced an opposite trend. The possibility of an all-out struggle in the Japanese home islands gave increasing significance to the chemicals, incendiaries, and smoke in the CWS arsenal and kept the rate of CWS distribution high. It was at this point, as noted above, that the CWS workload at the west coast ports rose to its peak. Then in August came the sudden surrender and the end of hostilities. The CWS effort, like that of the rest of the armed forces, made a full about turn. The storage and distribution network that had grown in four years from a single small depot to a system embracing ten major storage installations and as many port of embarkation sections, prepared to face the new responsibilities of demobilization.