Chapter 8: France, Belgium, and Germany

Breaking out of Normandy, the Allied armies quickly drove south and west into Brittany and surged eastward across northern France. By late August 1944 they had overrun the territory slated in OVERLORD for capture by D plus 90, with the exception of the principal Brittany ports, and in addition they had captured Paris and established bridgeheads across the Seine. Following on the heels of the retreating and disorganized enemy forces, the Allies moved weeks, then months ahead of the tactical timetable. Meanwhile, the DRAGOON forces had invaded southern France and had driven swiftly toward a junction with the armies to the north. At the end of September the Allies had gained possession of practically all of France, Luxembourg, and Belgium, and the southern part of Holland.1

Transportation in Relation to Tactical Developments

The rapid advance across France soon outstripped the means of logistical support, forcing constant readjustment of plans, improvisation, and hand-to-mouth supply operations. From a transportation point of view two problems loomed large in sustaining the onrushing Allied forces: the development of sufficient port facilities to receive and clear the growing volume of men and materials arriving on the Continent; and the distribution of troops and supplies from the beach and port areas over greatly extended lines of communication. Neither of the problems was satisfactorily solved during the two months following the break-through.

Plans for the development of the Brittany ports were upset by stubborn German resistance and extensive enemy and Allied destruction of facilities. The urgent need for additional ports to augment Cherbourg, the invasion beaches, and the minor Normandy ports caused Allied transportation planners to reassess the port situation, and in September finally led to a decision to abandon the idea of a major port development in Brittany and to concentrate on the newly captured ports of Antwerp, Le Havre, and Rouen. In the absence of adequate discharge capacity, port congestion was chronic, and a growing number of ships had to be held offshore to serve, in effect, as floating warehouses.

The problem of providing transportation to the interior was even more pressing. The lengthening lines of communication and the increased requirements of the combat forces did not permit the

establishment of the planned series of base, intermediate, and advance depots, and created a growing gap between the Normandy supply installations and the forward areas. Transportation facilities were too limited to bridge the gap. Rail line rehabilitation and pipeline construction were pushed forward vigorously, but they simply could not keep pace with the advancing armies. The main reliance had to be placed upon motor transport. Aside from performing the essential tasks of port clearance and base hauling, trucks carried the bulk of the troops and supplies that were moved forward during this period. As transportation planners had feared, there were not enough drivers and equipment to meet the needs. Minimum requirements were met only by overworking the men and vehicles, neglecting proper maintenance, and diverting trucks from port clearance and other essential work. Supplementing the overland carriers, air supply played a minor but important role in meeting emergency needs of the tactical forces.2

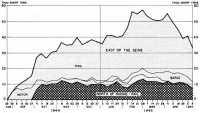

Overextended supply lines and increased German resistance brought the Allied advance to a virtual halt by the latter part of September. The relatively stable period that followed was marked by an improved transportation situation. The ports of Le Havre and Rouen were placed in operation, taking up some of the slack caused by the failure to open the Brittany ports and making it possible to close the beaches and a number of minor Normandy ports. Cherbourg continued as a major port, although it never attained its planned discharge capacity, and in the south Marseille satisfactorily handled traffic for the 6th Army Group. Considerable progress was made in rehabilitating the railways, which then took over an increasing share of the burden from the hard-pressed motor transport facilities.

The great turning point in the development of transportation operations was the opening of Antwerp on 28 November 1944. The huge port had been captured virtually intact early in September, but it could not be used until the Germans had been cleared from the approaches to the Scheldt Estuary. Possessing sufficient facilities to handle the bulk of the incoming U.S. and British cargo and located far closer to the fighting front than the ports already in operation, Antwerp was a major factor in solving the tight interior transport situation. The opening of Antwerp, to be sure, did not immediately resolve all transportation difficulties. It took some time to dissipate the shipping congestion; port clearance remained a limiting factor; and other ports and lines of communication had to be kept in use. Nevertheless, placing Antwerp in operation made it possible to provide increasingly better transportation service and placed the logistical support of the Allied armies on a far sounder basis.

New difficulties were encountered during the German Ardennes counteroffensive of December 1944—January 1945, when cargo piled up at Antwerp, movements to threatened areas were embargoed, motor transport was diverted to handle emergency shifts of men and materials, and bitter winter weather handicapped all operations. The setback was only temporary, and dislocations in the transportation system were rapidly corrected once the crisis had passed and the tactical situation improved.

The Allied armies resumed the offensive early in February 1945, and in March

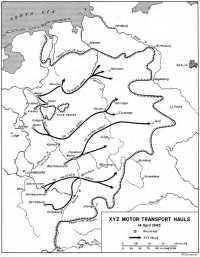

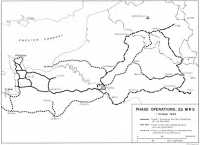

they crossed the Rhine. The ensuing eastward drive from the Rhine to the Elbe was in some respects reminiscent of the advance following the St. Lô break-through, but this time there was no comparable transportation crisis. With Antwerp in full operation and Ghent coming into the picture, port capacity was ample. For overland transportation detailed plans had been worked out in late 1944 and early 1945 for the support of the offensive, including provisions for extending rail and highway operations to, across, and beyond the Rhine. Rail lines were pushed forward rapidly, bridges were opened, and beginning in April an increasing proportion of the tonnage moved east of the river was carried by rail. As in the earlier advance, the railroads were outdistanced by the tactical forces. Although air supply was increasingly important in meeting urgent needs in the forward areas, the brunt of the transportation burden fell on motor transport. The required over-the-road hauling was effected through the so-called XYZ project, involving trucking operations over a system of highway routes established behind the onrushing American armies. Carefully planned and well organized, XYZ proved to be the largest and most successful of the long-haul trucking operations of the war.3

With the achievement of victory in Europe, the transportation effort shifted to vital postwar tasks. Redeployment and then repatriation of the bulk of the massive U.S. force built up in the theater were huge and complex undertakings. Special projects, including the movement to the United States of patients, recovered American military personnel, and war brides, also had to be carried through. Over and above these programs, there remained the significant and long-term job of supporting U.S. occupation forces in Europe. Having established itself as an essential service during the wartime years, the Transportation Corps continued important as a permanent part of the peacetime Army.

The Evolution of the Transportation Organization

Until February 1945 two major U.S. Army transportation headquarters existed in France. In the north, General Ross’s Transportation Corps headquarters was transplanted from the United Kingdom to handle planning and staff functions relating to transportation and to supervise marine, rail, highway, and movement control activities in the ETO communications zone. In the south, where the advance echelon of COMZONE, MTOUSA (previously SOS, NATOUSA), was supplanted in November 1944 by the Southern Line of Communications headquarters, technical direction was exercised independently of Ross by the SOLOC Transportation Section, headed by General Stewart.4

Other transportation headquarters were established within the subordinate territorial commands set up under COMZONE and SOLOC. By the end of 1944 five contiguous base sections (Normandy, Brittany, Seine, Channel, and Oise) had been activated behind the mobile Advance Section in COMZONE. In

SOLOC, the Continental Advance Section had moved forward, and the Delta Base Section had taken over the territory behind it. As in the United Kingdom, the base and advance sections directed personnel and operations within their respective jurisdictions. Each had a transportation staff to supervise Transportation Corps activities and control intrasectional movements.5

Upon moving his headquarters to Valognes in August 1944, General Ross set about developing an effective working organization and turned to the formidable transportation tasks involved in supporting the advancing armies. The stay at Valognes was brief. Early in September the Transportation Corps, along with the rest of COMZONE headquarters, moved forward to Paris. From the beginning the Transportation Corps operated under great pressure. Expansion of port, rail, and motor transport capacities was imperative, and with the increase in the number of base sections heavy demands were made on the Transportation Corps for staff and operating personnel.6

In general, this headquarters was organized along the same lines as it had been in the United Kingdom. The principal divisions were Administration, Control and Planning, Supply, Movements, Marine Operations, Motor Transport Service, and the 2nd Military Railway Service. With the exception of an Inland Waterways Division, which was separated from the Marine Operations Division in November, the structure remained basically unchanged at the end of 1944.7

Although General Ross’s organization was marked by stability during 1944, it encountered considerable delay in attaining its full stature. As will be seen, the COMZONE G-4 controlled shipping and exercised important functions with regard to movements control. To the theater chief of transportation these activities appeared to be an unwarranted invasion of his sphere of operations. After prolonged controversy the matter was finally settled in his favor, and late in the year he was given authority to develop a port and supply movement program. Subsequently, the control of shipping also was turned over to him. Another important step in the direction of centralizing the direction of transportation activities was taken after General Somervell visited the theater. On his recommendation, the G-4 Transportation Section was transferred to Ross’s headquarters in February 1945.8

The attainment of a unified theater-wide transportation organization was achieved in February 1945. During that month SOLOC was dissolved, and the Delta Base Section and CONAD were brought directly under COMZONE headquarters. As part of the general reorganization, the functions and key personnel of the SOLOC Transportation

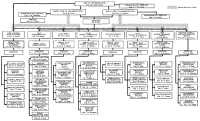

Section were absorbed by Transportation Corps headquarters in Paris. General Stewart became deputy chief of transportation, assuming responsibility for the supervision of movements and the operational services, exclusive of marine operations. Colonel Traub, previously the sole deputy chief of transportation, was assigned responsibility for the planning and administrative services. Since Traub was familiar with the shipping situation, he retained supervision of marine activities. At the same time a General Headquarters was established to coordinate the activities of the 1st and 2nd Military Railway Services, and its director was placed under the chief of transportation. No other significant organizational changes were made during the remainder of the war.9 (Chart 4)

After V-E Day, Transportation Corps headquarters was divided between France and Germany. Ordered by SHAEF to establish an office to direct transportation activities within the U.S. occupied area in Germany and to coordinate movements with other areas, the chief of transportation shifted part of his staff from Paris to Wiesbaden. He appointed an additional deputy, Col. Charles Z. Case, to head the new forward headquarters, which included Planning and Control, Movements, Motor Transport, and Administrative Divisions. The Office of the Chief of Transportation (Forward) continued to operate at Wiesbaden until 21 August 1945, when it was transferred to Frankfurt. Shortly thereafter, General Ross moved to the new location, dividing his time between Frankfurt and Paris. The division into forward (later main) and rear offices continued into the peacetime period.10

The Expansion of Port Capacity

The Allied offensive in the summer and early fall of 1944 accentuated the need for developing additional ports. Concentrating their main effort on the eastward pursuit of the retreating enemy, the tactical forces were unable to take Brest, Quiberon Bay, and Lorient on schedule. Other ports of potential importance in Brittany, including St. Nazaire and Nantes, also were denied to the Allies by the stubborn defense of German garrisons. As a result, the northern armies had to rely on the invasion beaches, Cherbourg, and the minor Normandy ports. The facilities barely sufficed to keep the Allied offensive rolling. The probability that over-the-beach operations would be severely curtailed by adverse weather beginning in September lent additional urgency to the problem of securing other suitable deepwater ports.

As previously indicated, delays in implementing OVERLORD plans for port development had caused transportation planners to cast about in search of additional discharge capacity. By the end of July Cherbourg’s planned discharge targets had been greatly increased, but much rehabilitation was required before they could be attained. The minor Normandy ports were also being developed, and proposals were made to develop Cancale, in Brittany, as a substitute for Quiberon Bay. In August efforts were made to open the small Brittany ports that had been

Chart 4: Organization of the Office of the Chief of Transportation, COMZONE, ETOUSA: 1 April 1945

Source: Rpt, Consolidated Historical Report on Transportation Corps Activities in the European Theater of Operations, May 1942 Through V-E Day, Chart VII, OCT HB ETO.

captured, including St. Malo, Cancale, St. Brieuc, and Morlaix.

Prospects for major port development in Brittany faded in September, as the enemy continued to cling tenaciously to key points and as the Allied forces drove farther eastward. Early in the month General Ross reported that the Quiberon Bay project was “definitely out,” in view of the impracticability of getting tows from the United Kingdom into the Bay of Biscay at that time of year. Brest was captured on 17 September but was so badly damaged that it was not worth rehabilitating. The Lorient–St. Nazaire area remained in enemy hands throughout the war.

During the same month, meanwhile, the advancing forces had uncovered Le Havre, Rouen, and Antwerp. While Le Havre and Rouen had suffered extensive damage, Antwerp was taken virtually intact, a development that even the most optimistic planner could not have foreseen. The prospective availability of these ports placed the entire matter of ship discharge in a new light.11

Until the newly captured ports could be placed in operation, the supply situation remained critical. In a communication to his major commands on 13 September 1944, General Eisenhower expressed his belief that the availability of additional deepwater ports was prerequisite to a final invasion of Germany. The current port situation was such that a week or ten days of bad channel weather might well “paralyze” the Allied effort. In order to support the Allied forces, Eisenhower stated, it would be necessary to secure the approaches to Antwerp or Rotterdam and to capture additional Channel ports.12

Shortly thereafter, in a communication to Eisenhower, General Lee noted that while tactical progress had exceeded expectations, port development was still behind schedule. In Lee’s opinion the development of Brest and the other principal Brittany ports to the tonnage previously planned was impracticable. Since Le Havre was reported seriously damaged and since its location did not materially shorten the lines of communications, he recommended that it be placed in operation as rapidly as possible but with a minimum expenditure for reconstruction. Lee recommended that the major port development be confined to Cherbourg, Le Havre, and Antwerp.13

The port problem underwent continuous study during the month, and on 27 September COMZONE issued a revised port development directive tailored to the current tactical and logistical situation. The main emphasis was now placed on the development of Antwerp, Le Havre, and Rouen.14 Under the new plan, Antwerp was slated to become the major British-American port on the Continent. Le Havre would be immediately developed to receive cargo from Liberty ships

discharging into DUKWs or lighters, and its capacity would be eventually increased to 7,000 tons per day. Rouen was scheduled to discharge 3,000 tons daily from coasters. Until Antwerp became available, Cherbourg would be used at maximum capacity, and although unfavorable weather would reduce their intake the beaches would have to be kept open. Of the minor Normandy ports, Grandcamp-les-Bains was closed; Granville was designated for coal discharge only; and the coaster ports of Barfleur, St. Vaast-la-Hougue, and Isigny were to continue in operation on second priority.

By this time, the Brittany ports had ceased to be an important consideration. With regard to Brest, plans were made only for a survey regarding its possible future use and development. Cancale was abandoned before it was opened, and port reconstruction work at St. Malo had stopped. Only Morlaix and St. Brieuc were scheduled for continued operation.15

With the opening of Le Havre and Rouen in October, the port situation improved somewhat, making possible the elimination of minor or expensive operations. Early in November 1944 General Eisenhower made available to the French St. Brieuc, Barfleur, St. Vaast-la-Hougue, Carentan, Grandcamp-les-Bains, and Isigny—shallow-draft ports that the Allies no longer required. The invasion beaches, where operations had been severely curtailed by bad weather and high seas, were closed later in the month.16

While Le Havre and Rouen furnished some relief, no real solution to the problem of port capacity was possible until Antwerp could be opened. This was delayed until late November because of the difficulty of clearing the Germans from the approaches to the port. During this period the Allies were denied the port facilities and the shortened lines of communication required for the adequate support of the tactical forces.

Once Antwerp came “into production,” port capacity was no longer a serious problem. Thereafter, the emphasis in planning shifted from port discharge to port clearance and inland distribution. The subsequent opening of Ghent increased the port reception capacity on the Continent still further and provided insurance should the enemy interfere with operations at Antwerp. No additional ports were opened until after V-E Day.17

The Problem of Shipping Congestion

The prolonged delay in attaining adequate port capacity, coupled with expanding military requirements and other conditions, resulted in a growing backlog of undischarged cargo vessels in European waters. Early in July 1944 the War Department manifested anxiety over excessive retentions of cargo ships in the European theater. During the following months, in view of the critical shipping situation throughout the world, the commanders of the European and North African theaters were urged to release and return cargo vessels as quickly as possible.

The problem was especially serious in northern France where the bulk of the shipping to support the invasion had been concentrated off the coast of Normandy.18

The War Department advised the European theater on 31 August 1944 that the theater was retaining too many vessels and so was interfering seriously with the availability of ships for other theaters. Accordingly, the currently scheduled sailings were to be cut by sixty vessels at the rate of ten per convoy. The theater protested that it wanted to crowd in the maximum tonnage for August and September before the equinoctial storms, but computations in Washington indicated that the existing program of sailings from the United States exceeded possible discharge on the Continent and the reduction was made.19

By October 1944 the shipping situation in northern France had become worse. Therefore, early in that month, the War Department advised the theater that sailings for the last quarter of the year would be scheduled in accordance with demonstrated ability to discharge, in order to reduce the backlog to about seventy-five vessels. General Gross, in particular, considered the theater’s discharge estimates too high on the basis of past performance and too wasteful of shipping. The theater again protested the cut; it expected the discharge rate to increase rapidly, and it also believed that the employment of ships as floating warehouses could be justified.

The number of idle ships in European waters continued to mount. The anticipated rate of cargo discharge failed to materialize, in part because of storms, rain, and mud, which hampered unloading and clearance. The previously projected opening dates of additional ports, notably Antwerp, were not realized. Although Eisenhower and Lee made personal pleas for more ships, citing the grave status of their ammunition supply, the War Department remained adamant. The situation, said Somervell, did not permit the use of ships for base depot storage.20

Recalling how effectively shipping had been controlled in the United Kingdom, General Gross concluded that in France the influence of the theater chief of transportation had waned. The shipping tie-up in Europe, he asserted, was delaying operations in the Pacific and postponing the end of the war. Accordingly, with the approval of the theater, he detailed his director of water transportation, Brig. Gen. John M. Franklin, to the theater “to suggest means to improve the discharge rate, to discourage the huge assembly of ships for storage purposes, and to give appropriate emphasis to the fundamental need to use shipping efficiently.” Franklin, a former shipping executive with considerable prestige, arrived in Paris on 28 October 1944. To help him in his mission General Ross placed Franklin in charge of the Marine Operations Division. Gross hoped

that with Franklin’s help Ross would be restored to a dominant status in the control of shipping at General Lee’s headquarters. The seriousness of the situation is shown by the fact that of the 243 cargo vessels in the theater on 30 October only about 60 were actually being discharged.21

General Franklin reported that Ross had been sidetracked and that the COM-ZONE G-4, Brig. Gen. James H. Stratton, was exercising complete control over the berthing and discharge of vessels. Shipping from the United States to the theater was scheduled on the basis of requests drawn up by the G-4 Section, “with only nominal coordination” with the theater chief of transportation. Franklin termed the G-4 estimates of cargo discharge “completely erroneous.” In a series of high-level theater conferences, in which General Eisenhower participated, Franklin stressed and secured the acceptance of the principle that the theater’s calculation of shipping requirements must be subject to continuing review and revision. Like Gross, Franklin believed that the basic problem was not a lack of ships but the discharge performance in the theater. With the assistance of two officers of the Water Division in Washington, Franklin therefore undertook a survey of cargo-discharge and port-clearance capacities on the Continent with a view to obtaining a sound basis for realistic estimates.22

During November 1944, despite vigorous efforts to expedite the release and return of ships, no appreciable drop occurred in the number of idle vessels awaiting discharge. In part, this situation reflected the setback from the severe October storms, but basically it stemmed from the inability to develop adequate port discharge and clearance capacity. Antwerp, although consistently and optimistically included in theater estimates of port capacity, did not begin cargo operations until 28 November, and it gained little momentum before mid-December. The theater’s continued failure to meet the target for discharge of cargo stimulated the growth of skepticism in the War Department as to the value of the ETOUSA estimates and led to a renewed determination not to dispatch additional ships to the theater until the existing backlog had been reduced.23

Late in November General Eisenhower sent several senior staff officers including three major generals (Lucius D. Clay, Harold R. Bull, and Royal B. Lord) to Washington to explain in detail his serious ammunition and shipping situation. General Franklin accompanied the party. The ensuing discussion at the War Department brought no significant change in policy. As before, the War Department was willing to give the theater all the ships it needed, provided they could be discharged promptly.24

Upon return of the theater delegation to Paris early in December, a Shipping Control Committee was set up. It was composed of General Lord, Chief of Staff, COMZONE, General Stratton, Assistant Chief of Staff, G-4, COMZONE, and General Franklin as the representative of the theater chief of transportation. This committee, whose basic task was to effect the requisite coordination between supply and transportation, was designated as the agency through which all shipping matters were to be cleared with the War Department. It was to receive requests for the allocation of shipping, which the G-4 originated on the basis of tonnage requirements, and to scale them down to the estimated capacity for reception. To insure proper allocation of vessels to discharge ports and to reduce turnaround a Diversion Committee was formed. Headed by the Transportation Corps Control and Planning Division chief of the theater, the committee included representatives of the COMZONE G-4, the technical services, and the Transportation Corps Operations and Movements Divisions.25

Meanwhile, the impact of the worldwide shipping shortage had made itself felt at the highest level in Washington. The Joint Chiefs of Staff and the War Shipping Administrator, whose vessels in large numbers had long been immobilized overseas, presented the matter to the President in November 1944. In accordance with instructions from the President, the Joint Chiefs in December issued a directive designed to improve the utilization of vessels in the overseas commands. Applied to all theaters, it prohibited the use of oceangoing vessels as floating warehouses, banned partial or selective discharge except in emergency, and enjoined a realistic appreciation of port and discharge capacity in arriving at shipping requirements. A system of weekly ship activity reports (short title, ACTREP) also was instituted to provide prompt and uniform information for all interested agencies in Washington.26 The tide had already begun to turn in Europe when this action was taken. After Antwerp became available for cargo discharge, the reserve of commodity loaders began to melt away.

However, more rapid improvement of the shipping situation was hindered by the fact that more cargo could be discharged than could be promptly forwarded by the available inland transport. Even after additional rail facilities had been obtained, the restricted capacity of the forward depots to receive cargo was a serious limiting factor, and this difficulty was intensified by the absence of intermediate depots. Temporary relief was secured by storing cargo in the port area, a practice that was also adopted at Le Havre. By mid-December thirty or more vessels could be worked simultaneously at Antwerp, and each could be turned around in ten or eleven days.

The ensuing German counteroffensive temporarily checked progress in clearing the shipping backlog. At Antwerp for a time vessel discharge was curtailed, additional cargo accumulated on the quays, and with the exception of critical items forward movement of cargo was further restricted. The port congestion was soon relieved, once the enemy threat was turned

back and port clearance operations were expanded. The result was that ships that had idled as floating depots for months at last could be sent home.27

On 19 January 1945 General Franklin reported the accomplishment of the War Department objective of bringing the theater’s cargo shipping and discharge program into substantial balance. Between 30 October 1944 and 7 January 1945 the number of cargo vessels in the theater had been reduced from 243 to 99. He also noted the need of intermediate depots with sufficient capacity to absorb tonnage that the forward dumps could not receive. Such depots, although deemed essential to prevent port congestion and long desired by the theater, had not yet been established.28 On 17 February General Lord, on behalf of General Lee, assured General Somervell that there would be no excessive accumulation of idle ships and that he would see to it that his staff maintained “a vigilant and accurate estimate of the situation at all times.” Both the discharge rate and the forward movements from the ports, he reported, were finally showing signs of consistent improvement. By late March 1945 General Gross was satisfied with the shipping and transportation situation in the European theater.29

U.S. Army Port Operations

Despite the delay in developing the port discharge and depot capacities envisaged in OVERLORD and the consequent shipping congestion, the U.S. Army-operated beaches and ports in France and Belgium handled an enormous volume of traffic originating in the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Mediterranean. Between the invasion of Normandy and 8 May 1945, approximately eleven months, they discharged 15,272,412 long tons of Army cargo and handled the debarkation of 3,702,180 personnel. In most cases, port operations were handicapped by extensive destruction of facilities, personnel and equipment shortages, and limited means of transportation to the interior. The workloads carried by the various Army port and beach installations during this period are indicated in the following table:30

| Ports | Cargo Discharged (Long Tons) | Personnel Debarked |

| Southern France | 4,123,794 | 905,512 |

| Cherbourg | 2,697,341 | 95,923 |

| Antwerp | 2,658,000 | 333 |

| OMAHA Beach | 1,264,999 | 801,000 |

| Le Havre | 1,168,171 | 1,014,036 |

| Rouen | 1,164,511 | 82,199 |

| UTAH Beach | 726,014 | 801,005 |

| Ghent | 614,861 | 6 |

| Minor Normandy | 600,884 | 788 |

| Brittany | 253,837 | 1,378 |

Cherbourg

The first major port on the Continent to fall into American hands, Cherbourg, had begun operations on 16 July 1944. Late in the month, the port was given the objective of discharging 20,000 tons per day by mid-September 1944. An expanded program for the rehabilitation of the shattered port facilities was undertaken by the Engineers and plans were made to provide additional unloading equipment and to improve rail and highway facilities.31

During the summer and fall of 1944 every effort was exerted to reach the desired daily discharge of 20,000 tons, but progress was disappointingly slow. Mine sweeping and ship salvage proved more difficult than anticipated, causing delays in port reconstruction. Cargo operations were carried on around the clock, but night work was slowed by poor lighting. Manpower was insufficient, despite the employment of thousands of prisoners of war and hundreds of French civilians. As winter approached, inclement weather often interrupted the port activity, and in September, alone, ten days were lost. Also, much of the incoming cargo consisted of bulky construction and rail rehabilitation materials, items that were difficult to handle expeditiously. Diversion of trucks and rolling stock from Cherbourg to hauls along the lengthening supply lines further handicapped port operations.32

Although General Ross had warned that the goal of 20,000 tons per day might not be achieved if passenger traffic were allowed to interfere with cargo operations, American troops began debarking at Cherbourg as early as July. In anticipation of additional troop movements, suitable space for staging areas was found southeast of the city. Evacuation of casualties was started in mid-August and was an important port activity thereafter. On 7 September 1944 the first troop convoy of four ships arrived direct from the United States, carrying approximately 19,000 military personnel who were unloaded by means of barges and rhinos. During that month a total of 67,022 troops landed at Cherbourg, and 5,059 casualties were evacuated. These passenger movements, while not extraordinarily heavy, had an adverse effect upon cargo discharge since they tied up badly needed floating equipment and port personnel.33

After discharging 12,911 long tons on 30 August, the port hit a new high of 14,426 long tons on 18 September. During the remainder of the month, the tonnage unloaded daily fluctuated between 8,150 and 13,888 long tons. Notwithstanding the difficulties already mentioned, the port commander, Colonel Sibley, believed that the main deterrent to the accomplishment of the port’s mission was the delay in reconstructing sufficient deepwater berths. On 14 September 1944 the port rehabilitation program was reported 75 percent complete, but a large part of this work consisted of lighterage facilities and the uncompleted 25 percent consisted chiefly of berths where cargo could be discharged directly from ship to shore. At that time, only five of twenty-eight planned Liberty

berths were available. The lack of deep-water docks compelled the port to rely heavily on lighterage, a process that required double handling and inevitably slowed cargo discharge. Of the 439,660 long tons of Army cargo discharged at Cherbourg by 13 September, only 38.4 percent was unloaded directly at quayside or at special LST ramps. The remaining tonnage was carried ashore from ships at anchor by DUKWs, barges, and other craft.34

Other problems arose in the realm of administration. As in the United Kingdom, the ports on the Continent were under the jurisdiction of the base sections. The Normandy Base Section commander, with headquarters at Cherbourg, took an active part in the direction of the port activities, and in Colonel Sibley’s opinion prevented the port commander from effectively exercising his authority. Moreover, the presence of base section headquarters, as well as various naval headquarters, served to crowd the port area and added to the congestion.35

Colonel Sibley was relieved on 19 September 1944 and was succeeded late in the month by Col. James A. Crothers.36 During the following month continued progress was made in rehabilitating the port as much additional cargo-handling, marine, motor transport, and rail equipment and personnel became available. Improvement was also reported in the maintenance and repair of port equipment. A growing percentage of the cargo was discharged directly at dockside, and despite worsening weather conditions the average daily discharge rose from 10,481 tons in September to 11,793 long tons in October.37

As cargo discharge operations improved, port clearance became the principal limiting factor. By October it had become apparent that although it was physically possible to unload 20,000 tons of cargo per day, this objective was being blocked by the difficulty of moving cargo forward once it had been placed ashore. There it tended to pile up, awaiting transport. As at any port, when clearance failed to keep up with discharge congestion developed. The continuous fall rains brought thick mud and impassable roads and caused trucks to bog down at the dumps. Motor transport for port use was severely limited by the demands of the rapidly advancing armies. As a result, greater use had to be made of rail facilities.

General Ross had foreseen that rail facilities would have to be greatly expanded and ultimately relied upon for most quay clearance at Cherbourg. Accordingly, an additional ninety miles of track were constructed within the port area. At his insistence, two large marshaling yards were built outside the city. The 4th Port also took over the operation of the Cherbourg Terminal Railway from the Normandy Base Section in order to achieve control and coordination of port and rail activity.38

Until August 1944 port clearance at Cherbourg was effected mostly by motor transport, but thereafter rail traffic increased rapidly. In September almost as much cargo was dispatched by rail as by truck. Beginning in October, movement by rail took the lead as additional trackage became available and more trains were placed in operation. The following are the comparative figures, in long tons, for cargo discharge and port clearance by rail and by truck during the last half of 1944:39

| Cargo Discharged | Cleared by Rail | Cleared by Truck | |

| July | 31,627 | 1,212 | 27,257 |

| August | 266,444 | 94,692 | 152,731 |

| September | 314,431 | 162,021 | 166,118 |

| October | 365,592 | 191,307 | 161,814 |

| November | 433,301 | 242,004 | 150,026 |

| December | 250,112 | 155,797 | 97,202 |

The peak in cargo discharge at Cherbourg was reached during November 1944, and on one day the 20,000-ton target was almost reached. An abrupt drop in December brought the discharged cargo down to about the August level, where it remained during the first quarter of 1945. The decline was due primarily to the opening of other ports—Rouen, Le Havre, and Antwerp—which were closer to the combat zone. Cherbourg remained useful, particularly for the discharge of ammunition, which was not moved through Antwerp because of the buzz bombs.

After November 1944 Cherbourg steadily declined as a major port. In the process of slackening off, much of its cargo-handling equipment was turned over to other installations. After V-E Day Cherbourg was used chiefly for the evacuation of patients. The port was returned to French control on 14 October 1945.40

The Brittany Ports

The supply problem of the U.S. forces was so pressing and the lag in cargo discharge so serious that every effort had to be made to develop auxiliary ports, no matter how small. With the Allied advance following the St. Lô break-through, a number of northern Brittany ports, including St. Malo, Cancale, Morlaix, St. Brieuc, and St. Michel-en-Grève, became available. The job of operating these installations was assigned to the 16th Port under General Hoge, former commander of the Engineer Special Brigade Group at OMAHA Beach.

Early in August 1944 General Hoge flew to France with an advance party, which was followed later in the same month by the main body of the port organization. Preliminary reconnaissance disclosed that the beaches at Cancale and St. Malo were not usable and that the lock gates at St. Brieuc had been severely damaged. On 11 August the 16th Port was ordered to discharge three LSTs that had just arrived at St. Michel-en-Grève with trucks, ammunition, rations, and miscellaneous supplies urgently needed by the VIII Corps of General Patton’s Third Army. The unloading, which began on the following day when the beach had dried out, was completed in sixteen hours. Later, other LSTs were discharged here in similar fashion. Meanwhile, operations also started at Morlaix. In September

1944 the 16th Port was relieved in this area by the 5th Port.41

The 5th Port found the facilities at Morlaix very poor. The retreating Germans had done some damage, but following reconstruction Morlaix and its sub-ports of Carentan, Roscoff, St. Michel-en-Grève, and St. Brieuc were serviceable, and they discharged and forwarded approximately 54,000 long tons of supplies in September 1944. At the tiny port of Roscoff more cargo was discharged and cleared every day than had been handled there in an entire year before the war. A small fleet of Army harbor boats, assisted by Navy landing craft and some local shipping, furnished the required water transportation. Through these minor installations flowed a steady though not heavy stream of ammunition, rations, and petroleum products for the support of the Third Army. The service of the 5th Port in Brittany was terminated in December 1944 when the unit transferred to Antwerp.42

Counted on heavily in OVERLORD planning, the Brittany ports played only a minor role in the support of the armies. Morlaix and its subports proved useful, but none of the larger ports was ever opened. As already indicated, enemy resistance, destruction of port facilities, and the rapid Allied progress eastward led to abandonment of the hope of any significant port development in Brittany. By the latter part of September, the emphasis in planning had shifted to ports recently uncovered by the advancing armies.

Le Havre

The port of Le Havre, at the mouth of the Seine River, had suffered severely from Allied artillery and air attacks and from enemy demolition. As planned in late September 1944, the port development program called for the immediate reception of approximately 1,500 long tons per day by means of DUKWs or lighters and an eventual discharge of about 7,000 long tons per day. This was to be accomplished without major reconstruction.43

The 16th Port, which was assigned to operate Le Havre, had completed its transfer from Brittany by the end of September 1944.44 Meanwhile, Engineer troops had arrived and had begun the job of rehabilitation. This work was scheduled for completion in three phases. In the first phase the Engineers cleared and prepared the beaches for operation, removed mines and booby traps, provided storage space, and built access roads. In the second phase emphasis was placed on the repair of quays and lighterage berths, the improvement of the road network, and the removal of sunken vessels. The latter job was done in close coordination with U.S. Navy salvage crews. The first phase was completed and the second well under way by the end of November. Thereafter work was concentrated on the provision of facilities of a more permanent nature—the third phase.45

Work was sufficiently advanced by 2 October 1944 to begin over-the-beach discharge from LSTs. Despite almost continuous rainfall, rehabilitation progressed and the discharge rate mounted steadily. By the end of the year the port troops, augmented by French civilians, had unloaded 434,920 long tons of cargo from a variety of vessels including Liberties, LSTs, refrigerator ships, and coasters.46 The bulk of the tonnage was discharged from ships at anchor into DUKWs, barges, and landing craft. As at other ports, operations were conducted around the clock.47

During the German counteroffensive of December 1944, Le Havre played an important role in supporting the hard-pressed U.S. forces. In that month the port dispatched ninety-two trainloads of ammunition to the forward area; critically needed rockets were rushed by truck from the port to troops defending a large depot at Liège; and certain types of small arms ammunition were given expedited handling.48

A major feat during this period was the rehanging of the gates of the Lock Rochemont. This project, participated in by Engineer and harbor craft troops, U.S. Navy salvage personnel, and French civilian contractors, opened the inner basins to Liberty ships. Despite adverse weather, underwater obstructions, and limited equipment, the job was finished at the end of November. The first Liberties passed through the lock on 16 December. Other important undertakings, completed early in the following year, involved the rehabilitation of the Tancarville Canal for barge traffic up the Seine from Le Havre, and the rehanging of the gates of the Bassine de-la-Citadelle.49

In January 1945 a peak monthly discharge of 198,768 long tons was achieved. Although quayside operations had assumed increased importance, DUKWs and barges continued to be the chief means of discharge. During the first quarter of the year the seven DUKW companies brought ashore 35.2 percent of the tonnage landed at Le Havre. Quayside discharge accounted for 23.3 percent of the total. Barges and other craft accounted for the remainder. The volume of inbound shipments—largely ammunition—continued heavy, and by 31 May 1945 Le Havre had received a total of 1,254,129 long tons of cargo.

Port clearance at first was effected by motor trucks, which rumbled through the debris to the dumps. Later, rail and canal facilities also were used to remove cargo from the port area, where suitable storage space was scarce. As elsewhere, port clearance activities were at first handicapped by insufficient ship-to-shore discharge facilities and by truck and rail equipment shortages. By early 1945, however, these conditions had been materially improved. The tonnage moved forward then exceeded that discharged, permitting the reduction of cargo previously accumulated in port storage.50

Aside from serving as a cargo port, Le Havre also developed into the principal troop debarkation point in the European theater. Debarkation activities became important in November 1944, and reached a peak during March 1945, when 247,607 personnel debarked. The landing of troops was facilitated by direct ship-to-shore operations at a long steel ponton pier and at a rehabilitated troopship berth at the Quai d’Escale. In mid-January 1945 the 52nd Port, newly arrived from the Bristol Channel, was attached to the 16th Port. Its commander, Col. William J. Deyo, was assigned the job of handling troop movements. During the same month the Red Horse Staging Area was established nearby to stage inbound and outbound personnel.51

With the coming of V-E Day, emphasis shifted from troop debarkation activities to outloading personnel. On 1 June 1945 the Le Havre Port of Embarkation was established and included the port, the depots, and the adjacent staging camps. During the month a total of 207,759 American military personnel embarked from Le Havre. The port was used for outbound American personnel, including war brides, until the end of July 1946, when this activity was assigned to the 17th Port at Bremerhaven, Germany.52

Rouen

U.S. Army activities at the Seine River port of Rouen were begun early in October 1944. A detachment of the 16th Port arrived to direct operations; rehabilitation and salvage activities were undertaken by the French, U.S. Army Engineer troops, and U.S. Navy personnel; and French civilians were hired to assist in the conduct of port activities. The first two ships, coasters carrying POL from the United Kingdom, were berthed on 15 October 1944.

After four days the 16th Port detachment was replaced by the 11th Port, which with its attached units had been transferred from the Normandy minor ports. There were then nine berths available, and rehabilitation was estimated to be 20 percent complete. The 11th Port commenced unloading activities on 20 October, and during the remainder of the month it discharged 23,844 long tons from forty-eight vessels, most of them coasters.53

At first, port operations were retarded by enemy destruction, inadequate railway facilities, a shortage of labor, and insufficient motor transport for cargo clearance. Also, larger cargo vessels, such as Liberties and MTVs, had to be loaded lightly or were lightened in order to negotiate the shallow channel between Le Havre and Rouen. As rehabilitation progressed, the port’s performance improved. During November 1944, the 11th Port discharged 127,569 long tons, and in December it unloaded 132,433 long tons. Meanwhile, troop debarkations had become important. Beginning with the debarkation of troops from an LSI on 10 November, Rouen by the end of the year had received

51,111 personnel and 22,078 vehicles, which arrived aboard LSTs, MTVs, coasters, and landing craft.

The port rehabilitation program was pushed to within 75 percent of completion by the close of 1944, and subsequently a total of fifteen Liberty and twenty-six coaster berths were made available. Activity reached a peak during March 1945, when the port discharged 268,174 long tons of cargo. At that time approximately 9,000 U.S. Army troops, 5,000 French civilians, and 9,000 prisoners of war were engaged in operations at Rouen. Traffic at the port fell off drastically after V-E Day, and on 15 June 1945 the port was returned to French control.54

Marseille

In contrast with the delayed port development in northern France, Marseille was brought into operation earlier than anticipated. When Marseille and its satellite, Port-de-Bouc, were captured late in August 1944, about a month ahead of schedule, operation was assigned to the 6th Port. Despite extensive destruction, rehabilitation proceeded rapidly, and by late September 1944 it was possible to close the beaches in southern France and rely on the ports to receive the men and materials required for the support of the 6th Army Group.55

During October prompt removal of cargo from the port area at Marseille became very difficult because of a shortage of motor transport. Large amounts of cargo were piled on the quays, many berths were idle, and on a single day as many as forty-four ships were awaiting discharge. In this emergency every available vehicle was seized for port clearance. Even horses and wagons were used. But since the backlog continued to mount, a temporary embargo had to be placed on sailings to Marseille from Italian and North African ports. The procurement of additional motor transport and the relatively rapid rehabilitation of rail facilities proved major factors in relieving this port congestion. By 1 November some 1,100 trucks were available for port clearance, the backlog of cargo awaiting removal had been reduced to normal, and the ports of Marseille and Port-de-Bouc were discharging and clearing an average rate of 16,000 long tons per day for five days each week.56

The 6th Port ran into a shortage of experienced labor at Marseille since the best dock hands had been removed by the Germans. Nevertheless, many indigenous workers were hired. In February 1945 an average of 7,339 French civilians worked each day in the dock area. The French served under their own supervisors but received U.S. Army rations to supplement their diet. Because the demand for labor exceeded the available supply, the port requested and received prisoners of war to assist in port operations. During the same month, in addition to French civilians, the daily labor force at Marseille included 1,268 Indochinese, 4,621 prisoners of war, and 5,646 U.S. troops. The large number of foreign workers accentuated the

pilferage problem. Efforts to minimize black market activity originating in the port were only partially successful, chiefly because of an insufficient number of military police to serve as guards.57

During November 1944 Marseille achieved a record of 486,574 long tons of cargo discharged. In the period from November 1944 through March 1945 the port unloaded a total of 2,249,389 long tons. For the same five months troop debarkation figures aggregated 269,579. Port-de-Bouc, in addition, had received large amounts of petroleum products, which in March 1945 alone totaled 162,245 long tons. By April 1945 the Army had sixty-eight berths available at Marseille. In the following month part of the port area was relinquished to French agencies for handling much-needed civilian foodstuffs and supplies.58

When V-E Day came the port of Marseille had discharged more U.S. Army tonnage than any other European port. It had also debarked a large number of American military troops in addition to forwarding prisoners of war to the zone of interior. Following the German surrender, Marseille was the principal port for direct redeployment of personnel, equipment, and supplies to the Pacific. Here were concentrated the “flatted” Liberties that were to transport organizational vehicles for the redeployed units. These were the ships originally requested by the theater to furnish vehicle lift and an emergency floating reserve of ammunition and subsistence for the invasion of southern France.59

After V-J Day the main mission of the 6th Port was to return troops and materiel to the zone of interior. The peak came in November 1945 when 139,785 troops and 41,062 long tons were outloaded. Activities at Port-de-Bouc were ended on 23 March 1946, and on the last day of that month all U.S. port operations ceased at Marseille.60

Antwerp

Situated on the Scheldt River about fifty-five miles from the sea, Antwerp had the important advantage of excellent shipping facilities, good connections with the hinterland, and proximity to the front lines. In peacetime Antwerp had been one of the world’s busiest ports with activity comparable to that of Hamburg and New York. Besides many modern docks equipped with 270 electric cranes, 322 hydraulic cranes, and much heavy lift equipment, the port had considerable shed and storage space, several large dry docks, and more than 400 connected tanks with a capacity of over 120 million gallons for petroleum products.

Since the Germans had left the port and its facilities relatively undamaged, no major reconstruction work was required. The river and harbor had to be swept of mines, and considerable dredging accomplished.61 Some sunken craft had to be cleared from the basins, sand and gravel

removed from the quays, and hard surfacing provided for fork lifts and other materials-handling equipment. The damaged gates of the Kruisschans Lock at the main entrance to the American sector had to be repaired, ripped-out rails replaced, and repairs to sheds, warehouses, and quay walls made. The rehabilitation work was performed by British and American military units, assisted by civilian labor. An early report indicated that the port of Antwerp was capable of meeting the combined requirements of the British and American Armies.62

Preliminary negotiations between the British and Americans had assured the latter a minimum of sixty-two working berths. On 14 October 1944 General Ross designated the chief of his Control and Planning Division, Col. Hugh A. Murrill, as his representative in the over-all planning for the development of the port. Ross, in particular, wanted the maximum freedom of operation accorded the U.S. port commander. Four days later a formal agreement was reached between the British 21 Army Group and the U.S. COMZONE headquarters providing for a division of the inner harbor, or basins, between the British and the Americans, and for the joint use of the outer harbor, that is, the docks along the river. Subject to later amendments, this agreement assigned a large portion of the northern section of the port to the U.S. Army and reserved the southern section, including the city of Antwerp, for the British forces.63

Under the agreement, the British assumed responsibility for the local administration and defense of the Antwerp area, while the Channel Base Section, COMZONE, was given the task of coordinating; controlling, and administering all U.S. forces within the area. Although over-all command of the port was vested in a British naval officer, the British and American sections were each headed by a separate port commander. The coordination of activities, including the determination of requirements for civilian labor and port equipment, was controlled through a Port Executive Committee, which was headed by the British naval officer in charge and included the British and American port commanders.

Provision also was made for the establishment of a joint American-British movements and transportation committee to plan and coordinate movements by highway, rail, and canal. After a Belgian representative had been included, this committee became known as BELMOT (Belgian Movements Organization for Transport). Insofar as possible, American cargo was to be moved from quayside to advanced depots, and any storage in the port area was to be of an in-transit character. It was estimated that the U.S. Army would move approximately 22,500 tons of cargo per day, exclusive of bulk POL, to its depots in the Liège–Namur and Luxembourg areas. The British were expected to move 17,500 tons daily, exclusive of bulk POL, to their forward depots.64

The 13th Port, previously stationed at Plymouth, was assigned initially to Antwerp. Its personnel began arriving in October 1944. Later, the 5th Port also was moved to Antwerp, coming in two detachments during November and December. Technically, the 5th Port was attached to the 13th Port, but the officers and men were placed wherever needed so as to form a single working organization. The headquarters companies of the two ports remained separate. In command of this combined organization was Col. Doswell Gullatt, who formerly headed the 5th Engineer Special Brigade at OMAHA Beach.65

The first American cargo vessel at Antwerp, the James B. Weaver, arrived on 28 November 1944 with men of the 268th Port Company and their organic equipment aboard. By mid-December the port at Antwerp was operating in high gear. The American section was divided into eight areas, each of which functioned as a unit. Cargo handling was greatly helped by the large amount of American equipment, notably harbor craft and cranes, brought in to supplement the Belgian port facilities. As the year closed, the pool of floating equipment was augmented by the arrival of 17 small tugs, 6 floating cranes-2 of 100-ton capacity-20 towboats, and a number of other harbor craft. Military personnel for the most part simply supervised cargo discharge, since the bulk of the unloading was done by Belgian longshoremen. The number of civilians employed by the U.S. Army steadily increased, and at the close of 1944 the average was approximately 9,000 per day. The principal problem was that of transporting the workers to and from their homes, since enemy activity had forced many natives into temporary quarters outside the city. During the winter of 1944–45, despite occasional short-lived strikes, the Belgian civilians on the whole performed excellently and proved both cooperative and industrious.66

Buzz bombs, rockets, and enemy air attacks often interrupted but never entirely halted port operations. Casualties, property damage, and frayed nerves were inevitable concomitants. In late October the persistent enemy bombardment of the Antwerp port area had aroused fear in the Army’s Operations Division at Washington that this might be another case of putting “all the eggs in one basket.67 In reply, the theater commander had stressed the importance of the additional port capacity. The defense of the city, he said, was being strengthened, but at the same time every other available port on the Continent was being developed to the maximum as insurance against disaster at Antwerp.”

Regardless of the grave hazards, port personnel soon succeeded in unloading more cargo than could be moved promptly to the dumps and railheads. Although cargo forwarding lagged behind vessel discharge, the rate of port clearance steadily improved. Rail clearance, initially limited by shortages of rolling stock, was stepped up, and by mid-December 1944 it outstripped other means of transportation from the port. During that month removal by rail accounted for 44 percent of all tonnage cleared, as against 40 percent for

motor transport. The inland waterways accounted for the remainder.

Normal port operations at Antwerp were interrupted by the German counteroffensive of mid-December 1944. Because outlying depots and dumps, particularly those in the Liège area, were threatened, large quantities of supplies again accumulated in the port. Items such as winter clothing, tanks, Bangalore torpedoes, jeeps, mortars, and snowplows were rushed to the front. Port personnel were diverted from their regular assignments to assist in the rescue of V-bomb victims and to guard supply trains moving into the forward areas. The port troops also formed road patrols and did sentry duty at vital dock installations in order to forestall possible attack by saboteurs and enemy paratroopers. Fog, icy roads, and bitter cold added to the operating difficulties.68

constant harassment by long-range V-1 and V-2 weapons and occasional bombing and strafing from aircraft, port activity continued at a steady pace. During December 1944 the impressive total of 427,592 long tons of cargo was taken off U.S. vessels at Antwerp. The nuisance bombing was countered by determined and effective defenders utilizing antiaircraft fire, radar screens, and every other modern protective device. Yet the bombs came through, bringing death and destruction. Despite the incessant noise and the constant terror, longshoremen worked feverishly around the clock. Lights burned all night, controlled by master switches for protection against enemy aircraft. A steady stream of trucks and trains moved the cargo forward to the armies.69

Early in 1945 the halting of the German Ardennes offensive, continued progress in the rehabilitation of port facilities, and the acquisition of additional harbor -craft and port equipment permitted substantial improvement in the amount of cargo moved through Antwerp.70 The following tabulation shows, in long tons, the cargo discharge and clearance at the port during the first half of 1945.71

| Cleared From Port by | |||||

| Month | Cargo Discharged | Rail | Road | Barge | Total |

| Jan | 432,756 | 238,518 | 120,799 | 41,616 | 400,933 |

| Feb | 473,473 | 306,036 | 169,469 | 57,868 | 533,373 |

| Mar | 557,585 | 302,018 | 184,169’ | 74,020 | 560,207 |

| Apr | 628,217 | 209,459 | 86,103 | 142,450 | 438,012 |

| May | 416,825 | 147,797 | 72,885 | 123,758 | 344,440 |

| Jun | 484,667 | 170,511 | 110,627 | 164,822 | 445,960 |

By V-E Day the American section of Antwerp had become the leading cargo port operated by the Transportation Corps in the European theater. After the close of hostilities the port did not lose its significance. In July 1945 ammunition, tanks, vehicles, and personnel were shipped to the Pacific. The capitulation of Japan led to a change in the outloading program, which thereafter was directed to the return of troops and equipment to the zone of interior. As at other ports, the frequent turnover of personnel and the progressive reduction of strength incident to redeployment and demobilization resulted in lowered operating efficiency. Because an adequate military guard could not be

maintained, cargo pilferage increased.72

The 5th Port was inactivated on 18 November 1945. In that month, despite the loss of many key men, 156,743 long tons of cargo were outloaded. The 13th Port remained as the headquarters unit at Antwerp. However, as the year drew to a close, activity was on the decline. On 31 October 1946 the 13th Major Port was inactivated and all U.S. Army port operations ceased.73

Ghent

The Belgian port of Ghent was opened in January 1945 under joint American and British operation to serve as a standby port for Antwerp. Having been used by the Germans only for barge traffic, the harbor had to be dredged and the port facilities rehabilitated. The 17th Port was assigned to Ghent, and on 23 January it began unloading the first cargo ship. A steady increase in American activity during the ensuing months culminated in a peak discharge in April of 277,553 long tons. Late in that month the Americans took complete charge of port facilities, except for a few berths reserved for the British. By 31 May a total of 793,456 long tons of U.S. Army cargo had been unloaded. On 24 June the 13th Port relieved the 17th Port at Ghent. The main body of the latter organization then proceeded to Bremerhaven, which was to be developed as the supply port for the American occupation forces in Germany and Austria.74 U.S. Army port operations ceased altogether in the last week of August 1945.75

Movement Control

Movement control operations on the Continent differed markedly from those in the United Kingdom. France lacked the well-organized military transportation system that existed in the British Isles and there was no established movement control organization upon which the U.S. Army could rely. Movement control on the Continent was further complicated by wartime damage or destruction. At the outset it was almost impossible to determine how much traffic might be handled in a given area. Movements therefore could not be planned, as in the United Kingdom, on the basis of known performance and a relatively predictable logistical situation. On the Continent the estimates of port, rail, and highway capacity were never free from the uncertainty inherent in a changing tactical situation.

The control of movements on the Continent was initially handled on a decentralized basis. As the advance and base sections were established, they set up movement control staffs within their transportation sections and assigned traffic regulating personnel to important rail terminals and truck traffic control points. On the Continent the RTO did much the same work as in the United Kingdom, performing the actual movement control operations in the field. Although under the technical supervision of the theater chief of transportation, the RTO was

directly responsible to the transportation officer of the base section in which he functioned.76

decentralized command structure, coupled with the intervention of the COMZONE G-4 in the realm of operations, delayed the development of centralized direction of supply movements by the theater chief of transportation until the end of 1944. Until that time, the commanders of the various base sections took almost complete responsibility for the control of movements originating in their respective areas. The “technical supervision” of the theater chief of transportation was construed in the narrowest sense, with the result that his personnel in the base sections refused to act without a movement order from the G-4, COMZONE, whose office therefore became an operating agency. The Freight Branch of the chief of transportation’s Movements Division was primarily advisory. There was no strong civilian organization, such as the British Ministry of War Transport that could bring pressure to bear on the supply services.77

The depots and dumps on the Continent generally were set up without consulting the theater chief of transportation and often without regard for limitations that he might have detected. Such practices resulted in many unsatisfactory locations being chosen, and rail and truck congestion followed because freight was scheduled for arrival at a rate beyond the capacity of the installation.78 Since many of the factors affecting the control of freight movement were unknown or variable, and since large reserves ashore were lacking, the supply of the U.S. Army usually was on a hand-to-mouth basis, governed by a system of priorities and daily allocations.

By late 1944 it was clear that the ability of the ports to discharge and forward cargo exceeded the combined receiving capacity of the U.S. Army depots. This situation called for a movements program geared to realistic goals. However, the priority system and movement control exercised by G-4, COMZONE, prevented the theater chief of transportation from effectively restricting and policing freight traffic in accordance with depot capacities. Moreover, the G-4 of each base section was free to use the movement capacity that remained after the priority allocations of G-4, COMZONE, had been met. This often led to the arrival of additional freight at depots that were already overburdened.

The period of extreme decentralization in movement control came to an end on 1 January 1945 with the publication of the first monthly port operations and supply program.79 The new program had its beginning in the daily allocation made for the Red Ball Express in late August 1944. Further impetus was given by the subsequent shipping crisis, in which it was demonstrated that cargo discharge, port clearance and forward movement would have to be planned on a realistic basis. Details of the new system were worked out in

periodic conferences with the chief of transportation, whose position, as has been pointed out, was greatly strengthened at this time.80 During March 1945 General Ross was also instrumental in establishing a workable procedure whereby an immediate embargo could be proclaimed to prevent congestion at a given depot. The monthly personnel and supply movement program, as it was later called, proved extremely useful during 1945.81

In order to effect the orderly movement of supplies and replacements into the combat zone and the prompt evacuation to the rear of casualties, prisoners of war, and salvage, provision was made for the assignment of regulating stations. This type of traffic control agency, a hold-over from World War I, should not be confused with the traffic regulating units, on which the Transportation Corps relied heavily throughout operations on the Continent. As a rule, a separate regulating station was established behind each army, commanded by a regulating officer who theoretically was the direct representative of the theater commander.82

As provided for in OVERLORD planning, the regulating officers serving each of the armies under the 12th Army Group were assigned to ADSEC, which then functioned as the armies’ regulating agency. When the 24th and 25th Regulating Stations reached France in late July 1944, no one clearly understood what was expected of such units since they had not been used previously. By mid-August, however, the 25th Regulating Station had begun to assist ADSEC in controlling the flow of supplies to the U.S. First Army, its mission until the German surrender.

Meanwhile, the 24th Regulating Station began supporting the fast-moving U.S. Third Army. Especially during August and early September 1944, the demand always exceeded the supply and the transportation facilities proved inadequate. Priorities of movement had to be established to prevent highway congestion, and shipments were forwarded on a day-to-day basis. Under these circumstances the unit did more expediting than regulating, a condition that lasted until December 1944. The 24th Regulating Station followed the Third Army into Germany, operating as a control agency in its support until the end of hostilities.83

In view of the extensive employment of motor transport on the Continent, the control of highway traffic became an important staff function of the theater chief of transportation and was assigned to his Movements Division. This work fell into two main phases. The initial phase obtained from D Day until about mid-August 1944. During this period, when the tactical situation was the governing factor, highway traffic was regulated by the U.S. First Army and ADSEC. The second phase began with the establishment of the office of the chief of transportation in France, when the Movements Division became responsible for highway traffic regulation and issued the necessary directives and procedures. For about three months it also issued motor movement instructions and made its own reconnaissance in the field. As soon as the base sections were

fully staffed and trained in the proper procedure, they took over this activity.

For security reasons as well as to facilitate communication, a key-letter system of recording and dispatching information on the movement of convoys and units was inaugurated by the theater chief of transportation. Coordination with civilian traffic agencies was achieved through two liaison officers, one French and the other Belgian, who were attached to the Movements Division. To supplement his small staff, General Ross requested fifteen civilian highway engineers from the United States. They began to arrive in December 1944 and were assigned where needed, but they might have proved more acceptable in the field had they been commissioned officers. The experience of the Movements Division indicated that traffic control on a decentralized basis, through the base sections, was the key to efficient traffic regulation.

At the close of hostilities in Europe the entire continental highway movement plan had to be altered to embrace the use of motor transport for the redeployment and readjustment of military personnel. Late in May 1945 a theater directive was issued that provided a complete standing operating procedure for such movements. To facilitate smooth and rapid transfer of personnel by highway from the army areas to the assembly areas and the port staging areas, a forward Road Traffic Branch was established at Wiesbaden, Germany, on 10 June 1945. It formed a helpful link between the armies and the theater chief of transportation.84

Motor Transport

By late August 1944 three types of truck operations had developed as planned: (1) so-called static operations, which included short hauls around depots and other installations; (2) port clearance; and (3) line of communications hauling, or long hauls. Static operations, though unspectacular, absorbed the bulk of motor equipment. Port clearance, which chiefly concerned cargo but might also involve troop movement, was essential to the smooth flow of supplies and troops into the combat zone and to insure the prompt return of ships to the United Kingdom and the zone of interior. Line of communications hauling had the most dramatic role in bringing lifeblood to rapidly moving armies.85

The main highways on the Continent were generally in good condition, thanks to reconstruction and repair by the Corps of Engineers. In a changing military situation, motor vehicles constituted the most flexible type of transportation, since they allowed hauls to be made to any location at any time and could be adapted readily to loads of varying weights and sizes. To meet the mounting demands of the advancing armies and to link the ports and beaches with the forward army supply areas, several express highway routes were established. But before describing these routes, it may be helpful to trace the principal developments with respect to the supply and operation of motor transport during the campaign on the Continent.86

Factors Affecting Operations

Throughout the summer of 1944 the burden laid on motor transport increased sharply, and the length of the hauls grew

greater as the Transportation Corps vainly tried to keep up with the armies. Had there been more truck units and more heavy-duty vehicles, the situation might never have become so acute, but the theater chief of transportation and his staff had not received the trucking units and heavy-duty cargo-hauling equipment that they had considered necessary for operations on the Continent. The resultant shortage in truck capacity was undoubtedly a factor in slowing the Allied advance, particularly that of the U.S. Third Army, across France in the summer and fall of 1944.87

Other factors also played a part. The Motor Transport Brigade (MTB) experienced considerable difficulty because of inadequate communications, congested highways, and frequent delays in loading and unloading. By late August 1944 the MTB had a daily lift of approximately 10,000 tons and the average haul was somewhat over 100 miles. At that time, General Ross reported that the rapid advance had proven extremely burdensome to the Transportation Corps and that only the trucks had saved the situation. It was, he added, pretty hard to keep pace with armies that covered in less than three months what they were expected to do in ten, especially when only one major port (Cherbourg) and the beaches were in operation.88

Despite the failure to get the motor transport that he wanted before D Day, the theater chief of transportation continued his efforts after the invasion. Then, as earlier, he had to contend with insufficient and inadequate equipment and inexperienced and untrained troops in hastily organized provisional truck companies. During the last half of 1944 General Ross tried to obtain additional trucking units and in particular to re-equip the 2½-ton standard companies with truck-tractors and 10-ton semitrailers that could carry a large pay load. Most of the re-equipping, begun in November, was accomplished by sending truck companies to Marseille where approximately 1,800 semitrailers and 690 truck-tractors had been discharged because of limited port capacity in northern France. After taking a short course in nomenclature and operation, these units brought the new heavy-duty equipment north from Marseille.89

Replacement of vehicles was a frequent necessity. Enemy action caused some damage, but the many accidents and mechanical failures due to inexperienced drivers and inefficient maintenance were the principal contributing factors. Because of constant wear and tear, the supply of tires and tubes for replacement became especially critical in the last quarter of 1944. Preventive measures were taken to ease the strain on such items, and late in the year the chief of transportation succeeded in procuring 16,053 tires and tubes of various types and sizes. Although the major supply problem in motor transport concerned vehicles, tires, and tubes, a host of other requirements developed, ranging from cotter pins to 750-gallon skid tanks. During this period the Motor Transport Service also stressed improved

maintenance procedures in an intensive effort to lessen the number of deadlined vehicles and to root out unsound practices.90