Chapter 10: The Southwest Pacific

War struck in the Pacific amid hasty efforts by the U.S. Army to strengthen the defenses of the Philippine Islands. After the attack on Pearl Harbor the Japanese for a time pushed steadily southward from their home islands. By mid-March 1942 they had taken most of the Philippines and had captured Hong Kong, Guam, Wake, Rabaul, Malaya, and Singapore, as well as the richest prize of all, the Netherlands East Indies. Japanese forces had already occupied Lae and Salamaua in New Guinea, and they threatened to isolate Australia. The remnants of the U.S. Army in the Philippines surrendered early in May. Shortly thereafter, in the Battle of the Coral Sea, Japanese aggression in the southwest Pacific was checked. Although the Allies were not yet ready to seize the offensive, the enemy had been halted. Ahead lay the long and painful climb up the island ladder of the Pacific, leading to the liberation of the Philippines and the capitulation of Japan.1 (Map 9) But before victory was achieved, many changes took place in the command, supply, and transportation picture.2

The Organizational and Logistical Setting

During the months immediately preceding Pearl Harbor, U.S. Army activity had quickened perceptibly in the Pacific. Late in July 1941 the U.S. Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE) had been established and placed under the command of Lt. Gen. (later General of the Army) Douglas MacArthur with headquarters at Manila. During the ensuing four months, as the storm clouds grew more ominous in the Far East, the reinforcement of MacArthur’s new command became a major concern of the War Department.3

While MacArthur’s men fought the Japanese invaders in a gallant delaying action, two other important Pacific commands came into being. The first was the American - British - Dutch - Australian (ABDA) Command, embracing Burma, Malaya, the Netherlands East Indies, the Philippines, and most of the north and northwest coast of Australia, which functioned only from 10 January to

25 February 1942.4 The second, entirely American, began with the impromptu Task Force, South Pacific.

Task Force, South Pacific, was constituted at sea on 12 December 1941 by Brig. Gen. (later Maj. Gen.) Julian F. Barnes, the senior officer aboard a U.S. Army troop and cargo convoy originally destined for the Philippines but diverted to Australia after America was drawn into the war. Escorted by the Navy and carrying approximately 4,600 U.S. Army personnel—chiefly Air Corps and Field Artillery troops-52 unassembled A-24 dive bombers, 18 P-40E fighters, about 340 motor vehicles, and sizable amounts of aviation oil and gasoline, bombs, and ammunition, the convoy reached Brisbane on 22 December 1941. On the same day General Barnes and his staff went ashore and established Headquarters, U.S. Forces in Australia (USFIA). USFIA, on 5 January 1942, was redesignated U.S. Army Forces in Australia (USAFIA).5

Ships of the convoy docked on 23 December 1941. The troops debarked and moved to tent quarters provided by the Australian Army. Cargo was discharged by Australian labor working around the clock and all through the Christmas holiday. Certain items were difficult to locate, and vital parts of the A-24’s, such as trigger motors, solenoids, and gun mounts, were never found.

For the Americans in Australia the prompt reinforcement of General MacArthur’s hard-pressed Americans and Filipinos had already become the supreme objective. Under the supervision of the quartermaster of Task Force, South Pacific, and with the help of the Australians, by 28 December 1941 the two fastest ships of the convoy were reloaded with U.S. Army troops, equipment, ammunition, and supplies for the Philippines. Because of the Japanese blockade these two vessels, the Willard A. Holbrook and the Bloemfontein, never reached that destination.6

Subsequently, in response to urgent appeals from General MacArthur and President Quezon, desperate attempts were repeatedly made to bring relief to the defenders of Bataan and Corregidor. Several small vessels were chartered as blockade runners and a few submarines carried critical cargo, but virtually all such efforts were unsuccessful. The Japanese air and sea blockade of the approaches to the Philippines effectively prevented substantial reinforcement either by ship or by airplane.7

Although the reinforcement of the Philippines remained the principal mission of the U.S. Forces in Australia for some time, as early as mid-December the War Department had decided also to establish on the continent a stable base capable of anchoring the Allied defenses in the southwest Pacific as a whole. With the deterioration of the Allied position in the Philippines and in the ABDA Command during the first months of 1942, emphasis shifted increasingly to the defense of Australia and its development as the main U.S. Army base in the area.8

Such an eventuality had not been anticipated before Pearl Harbor. The USAFIA staff, then headed by Maj. Gen. George H. Brett, was small, aggregating 23 officers and 13 enlisted men on 5 January 1942. Few of them possessed the experience necessary to deal with the formidable supply and transportation problems in the command. The first officer assigned from Washington to fill this need was Brig. Gen. Arthur R. Wilson. Accompanied by several assistants, General Wilson proceeded to Australia, arriving at Melbourne on 11 March. Ten days later he was appointed Chief Quartermaster, USAFIA, subsequently serving as Assistant Chief of Staff, G-4, in that command, until his return to the United States in late May 1942.9

The magnitude of General Wilson’s task may be gleaned from his instructions. Among other things, he was to survey and report on the local port and warehouse facilities, make recommendations as to reserves and levels of supply, and arrange for a system of local procurement. He was to charter all available craft in Australian waters in order to relieve the burden on American shipping, and he was to expedite the unloading and clearance of all troop and cargo vessels. “Finally and most important,” he was to spare no effort in getting food, ammunition, and other critical supplies forwarded to the Philippines and the Netherlands East Indies. Wilson carried out his mission with vigor and dispatch, although enemy action made effective compliance with the last part of his instructions almost impossible.10

Wilson and his staff discovered that Australia’s transport system left much to be desired.11 Except for a narrow coastal fringe, the continent was largely uninhabited desert. Judged by American standards the railroads were quite inadequate, and use of them was complicated by differences in gauges. Motor transport was handicapped by unimproved roads, an acute shortage of gasoline, and insufficient and unsatisfactory vehicles. The ocean linked the large cities along the coast, but water transport was hampered by a war-induced scarcity of ships. However unpromising, this was the transportation situation that confronted Wilson and his staff.

As Chief Quartermaster, USAFIA, General Wilson had both supply and transportation functions. Following the precedent newly established in the zone of interior, where transportation for the U.S. Army had been taken from The Quartermaster General and placed under a Chief of Transportation, Wilson recommended that a similar change be made in Australia. Despite initial disapproval by General Barnes, who clung to the old order, in mid-April 1942 General Wilson succeeded in setting up a separate U.S. Army Transportation Service, charged with the transportation duties previously assigned to the chief quartermaster.

Before his departure from the United States General Wilson had been instrumental in recruiting and commissioning from civilian life a number of experienced transportation executives, who began arriving in Australia in March and April 1942 to fill important positions involving water, rail, highway, and air traffic in Australia. These men included Thomas B. Wilson and Thomas G. Plant, each of whom was later to serve as theater chief of

transportation, as well as Paul W. Johnston, Roy R. Wilson, and Thomas F. Ryan, of whom the last three, respectively, had specialized in rail, highway, and air transportation. Apart from providing such top personnel, General Wilson gave energy and direction to the newly created U.S. Army Transportation Service, which unquestionably owed its early autonomy to his efforts.

USAFIA, including the Transportation Service, was placed under the new and vast Allied command established on 18 April 1942, when General MacArthur set up a general headquarters at Melbourne as Commander in Chief, Allied Forces in the Southwest Pacific Area (GHQ SWPA). As then constituted, SWPA included the Philippine Islands, the South China Sea, the Gulf of Siam, the Netherlands East Indies (except Sumatra), the Bismarck Archipelago, the Solomons, Australia, and the waters to the south.12 Some three months later, on 20 July 1942, USAFIA was succeeded by the U.S. Army Services of Supply (USASOS).13

Maj. Gen. Richard J. Marshall, the first USASOS commander, was succeeded early in September 1943 by Brig. Gen. (later Maj. Gen.) James L. Frink, who remained at the helm until 30 May 1945. Under General Frink USASOS continued to support huge military operations extending from Australia into New Guinea, Biak, and the Philippines. New bases were developed as needed and abandoned when no longer desired, all as part of the process familiarly known as the “roll-up” whereby men and materiel were pushed forward as the war progressed. Reflecting the change of scene dictated by tactical considerations Headquarters, USASOS, was transferred successively from Bris bane, Australia, in September 1944, to Hollandia, New Guinea; then to Tacloban, Leyte; and finally, in April 1945, to Manila.

The history of USASOS was characterized by constantly changing supply situations and repeated reorganizations to fit these changes. Arrangements suitable for one locale, such as New Guinea where bases had to be carved from the jungle, often proved undesirable in another, such as the Philippines. In general, USASOS headquarters tended to decentralize operational responsibility to the greatest extent to the base section commanders, whose domains flourished or faded in accordance with the varying requirements of each campaign. The commander of each base section maintained a transportation officer on his staff who was responsible for operations of the Transportation Corps within that section, under the technical supervision of the Chief of Transportation, USASOS.14

Beginning in the spring of 1945, the commands under General MacArthur, including both USAFFE and USASOS, entered another cycle of change, preparatory to the final drive against Japan. On 6 April, with the establishment of the U.S. Army Forces, Pacific (AFPAC), command of all U.S. Army Forces in the Pacific was given General MacArthur, thereby permitting him to operate north of the Philippines beyond the original confines of SWPA. USAFFE was absorbed by AFPAC

on 10 June. In the same month USASOS SWPA was replaced by the U.S. Army Forces, Western Pacific (AFWESPAC), under Lt. Gen. Wilhelm D. Styer, with headquarters at Manila. Following the close of hostilities SWPA disappeared, and on 17 September 1945 Headquarters, AFPAC, was transferred to Tokyo.15

Throughout World War II, several characteristics of the Southwest Pacific Area, either as a geographical entity or as a mélange of military organizations, profoundly affected the supply situation and, in particular, the task of the Transportation Corps.

Distances were enormous. San Francisco, the main port of embarkation supplying the Southwest Pacific, is 6,193 nautical miles from Brisbane, 5,800 from Milne Bay, 6,299 from Manila. Ships required more time to sail from the United States to SWPA and return than to any other area except China–Burma–India and the Persian Gulf. The long turnaround, coupled with the frequent retention of vessels for local service, severely taxed the limited available shipping.

Nearly all military operations took place within coastal areas. There were few interior railways and fewer inland waterways. The Army therefore was highly dependent upon ships and small craft to deliver its men and supplies.

Local transportation facilities were generally poor. Australian railways and highways were far from adequate; New Guinea had no railways, few roads, and only the most primitive and undeveloped ports; and the Philippines had suffered from wartime destruction. Throughout, American equipment and spare parts had to be supplied and new construction had to be undertaken.

Labor was often unsatisfactory. The best manpower of Australia was in military service, and the workers available to the U.S. Army were frequently slow and un-cooperative. The natives of New Guinea served willingly but were too few and too untrained to afford much assistance. Filipino labor, though good, was by no means entirely satisfactory. American service troops had to be used extensively in New Guinea and the Philippines, and their maintenance added to the transportation load.

Except in central and southern Australia, the theater was hot and humid. Rust, rot, mold, and vermin were ever-present plagues, and loss of supplies was bound to occur despite the most scrupulous care in packaging. Malaria, dysentery, and other tropical diseases, combined with the enervating effect of damp heat, undermined the efficiency of the service troops, especially in New Guinea, and swelled the number of patients requiring removal to more salubrious areas. Torrential rains and destructive typhoons hampered and on occasion halted transportation activity.

Naval, ground, and air forces of the United States, the Commonwealth of Australia, and to some extent the Netherlands East Indies were all engaged in transportation. Each operating force had its own organization and methods, but all competed for the limited resources in equipment and fuel.

Against this background in which the geographic, climatic, and military factors all contrived to complicate the task, the Transportation Corps sought to develop a working organization.

The Transportation Office

U.S. Army transportation in Australia began as a Quartermaster function performed by a pitifully small staff feeling its way in a strange land where the first American troops had arrived almost by chance. As originally constituted on 5 March 1942, the Transportation Division, Office of the Chief Quartermaster, USA-FIA, consisted of only one officer and one assistant. The organization hardly attained stature by 1 April 1942, when Col. (later Brig. Gen.) Thomas B. Wilson became deputy chief quartermaster and chief of the Transportation Division.

An alumnus of Kemper Military School and a veteran of World War I, Colonel Wilson had previously held civilian executive positions in the United States, involving rail, highway, water, and air transport. He was a natural selection to head the Transportation Service set up at Melbourne in mid-April 1942 to take over the transportation function from the chief quartermaster. The new chief of Transportation Service, USAFIA, was assigned a twofold mission: to coordinate the employment of all transportation for the U.S. Army; and to operate all transport acquired for its use, except that assigned to combat units, service organizations, or the Air Forces.16

Under Wilson a separate branch was established for each major type of transport. The principal activity in the new office involved water transport. The Rail Branch had only a secondary role, that of arranging and supervising the movement of U.S. Army personnel and supplies over the Australian railways. Motor transportation was negligible, since automotive equipment was organic to the base sections and to the divisions in training. Initially, the Air Branch established a useful chartered air service between the bases in Australia. Later, air transportation became a function of the Air Transport Command, and the transportation office simply provided a booking agency for airlift of U.S. Army passengers and freight.17

The Water Branch of the Transportation Service was headed at first by a former steamship operator, Col. Thomas G. Plant. His main concern was with the large ocean-going vessels bringing U.S. Army personnel and cargo to SWPA. Plant’s small staff arranged for and supervised the discharge and subsequent intra-theater activity of such ships, generally utilizing Australian stevedoring firms and dock workers.

Set up in 1942 and at first operating directly under USAFIA, the Small Ships Supply Command was charged with procuring, manning, maintaining, and operating a fleet of small craft for the U.S. Army in the waters north of Australia. Its vessels were used primarily to deliver ammunition, medical supplies, and perishable foods to outlying bases that could not be readily reached by large ships. The Small Ships Command also assisted when required in tactical operations and in emergency transfers of troops and equipment. Because of possible enemy action, its fleet carried both armament and gun crews. The Small Ships Supply Command, later called the Small Ships Division, came under the control of the Transportation Service on 29 May 1942. Thereafter, emphasis was laid upon the procurement in SWPA and in the United States of

additional small craft to satisfy the almost insatiable demands of the theater.18

In the first week of September 1942 the transportation office, with the rest of the USASOS headquarters, was removed from Melbourne to Sydney. By that time Melbourne was too far to the rear to be useful except for storage. As General Arthur Wilson had already said, using that city as a base for troops poised in northern Australia for a potential offensive in New Guinea was about like trying to operate from New Orleans, Louisiana, for action in the area around St. Paul, Minnesota. From the transportation standpoint the switch to Melbourne eliminated a troublesome change in railway gauge at Albury on the border of Victoria and New South Wales. Sydney had a further advantage in being able to accommodate deep-draft vessels.19

The next significant organizational change resulted from the reactivation at Brisbane on 26 February 1943 of the U.S. Army Forces in the Far East under the command of General MacArthur.20 An American theater headquarters essentially administrative in character, USAFFE interposed another echelon between GHQ SWPA, the Allied theater headquarters, and USASOS, the supply agency for U.S. Forces in SWPA. The chiefs of the several services, including the chief transportation officer, were now transferred from USASOS headquarters at Sydney to USAFFE headquarters at Brisbane, and the authority of USASOS was reduced to routine operational matters.

For the Transportation Corps, as well as the other services, the new arrangement presented a very awkward situation. From February to September 1943, two separate transportation offices had to be maintained, one for USAFFE and the other for USASOS. At Brisbane Colonel Thomas Wilson functioned as chief of transportation on the USAFFE Special Staff, assisted by a small number of key men engaged in planning and staff work for water, rail, air, and motor transport. At Sydney, as Transportation Officer, USASOS, Col. Melville McKinstry was made responsible for day-by-day operations. In order to keep in touch with McKinstry, Wilson had to make frequent calls over Australian telephones, for which he had no high regard. In his opinion the entire system of two offices was impractical, and it would have been much simpler if all his organization had been consolidated in one city. Actually, Brisbane lacked office space and housing for both USAFFE and USASOS, but in the late summer of 1943 as additional accommodations became available at Victoria Park, a progressive transfer of USASOS personnel was effected from Sydney to Brisbane.21

Two transportation offices were maintained in Brisbane until 27 September 1943, when the Office of the Chief of Transportation ceased to function in USAFFE and was returned to USASOS.22 In the same month General Frink, the

new USASOS commander, selected Colonel Plant to head up the consolidated transportation office, and arranged for him in turn to relieve Colonel McKinstry and General Thomas Wilson.23 General Gross, who was then visiting SWPA, was disturbed by the change. He believed that, as good men who were complementary, both Wilson and Plant should have been retained. Frink, however, was apparently sold on Plant as his transportation chief, and he preferred to have Wilson serve in some other capacity.24

Within a few weeks after this reshuffling had been completed, a new regulating system was established in GHQ SWPA, which subsequently was to have a far-reaching effect upon both USASOS and the Transportation Corps. Under Wilson as well as Plant, the transportation organization served not only the U.S. Army, Navy, and Air Forces but also the Australian military services. With a chronic shortage of tonnage and many claimants for shipping space, priorities had to be set. This problem was attacked in several ways and with varying degrees of success in the period before 12 November 1943, when a GHQ theater-wide regulating system was set up in SWPA under a chief regulating officer (CREGO), whose primary function was to control on a priority basis all personnel and cargo movements by water, rail, and air. Even opponents of the new regulating system ultimately acknowledged that its basic concept was sound and that it was necessary for GHQ to determine the respective priorities of shipment for the U.S. Army, Navy, and Air Forces and as between Americans and Australians. However, considerable difference of opinion developed as to the degree of control to be exercised, and as to whether the regulating system might not have worked better under the Chief Transportation Officer, USASOS, subject only to general priorities and tonnage allotments determined by GHQ. In any event, during the remainder of the wartime period the transportation office functioned in the deepening shadow of the GHQ regulating system.25

Colonel Plant fortunately encountered no difficulty with the chief regulating officer. As a matter of fact, during his comparatively brief tenure as Chief of Transportation Officer, USASOS, the regulating system was just starting and it therefore presented no serious problem. While Plant was in charge, no significant change occurred in the transportation office. Although his technical competence was beyond question, evidently and understandably Plant lacked familiarity with military procedures and organization. General Frink, desiring to get an officer who could see the picture “from a military standpoint,” relieved him on 8 April 1944.26 Plant was replaced by Col. (later Brig. Gen.) William W. Wanamaker, an officer without previous transportation experience. At Washington Generals Somervell and Gross were dismayed at the loss first of General Wilson and then Colonel

Plant, who were regarded as “transportation stalwarts.”27

A graduate of the U.S. Military Academy, Colonel Wanamaker had been trained as an engineer. He had come to SWPA in January 1944 to serve with the Sixth Army, which he left reluctantly when General Frink personally requested him for USASOS. The new assignment had been described as an excellent opportunity, and for Wanamaker it represented a real challenge. USASOS was no static command. As the center of activity shifted from Australia to New Guinea and thence to the Philippines, the organizational pattern of USASOS had to be adapted to a constantly changing supply and transportation situation. The necessary readjustment must have been especially trying for Wanamaker, since he had no previous experience to stand him in good stead. At the outset he discovered the need of new personnel, since several of his best officers were already suffering from malaria contracted in New Guinea. The base commanders did not always realize the importance of transportation, and Wana-maker’s organization frequently found its activity restricted by the GHQ regulating system.28

Wanamaker had hardly settled in his new niche when a wave of administrative change swept over USASOS. In May 1944 General Frink embarked upon a “work simplification” program, designed to promote greater operating efficiency in the command. An efficiency expert, Capt. Louis Janos, carried out the prescribed measures for the transportation office, which led to the elimination of three officers, thirteen enlisted men, five civilians, and many forms, reports, and other records. With respect to transportation, Wanamaker thought that this program was completely out of place and might well have been delayed until operations were less pressing and more stable. His problem was the bigger one of improving port operations, in the mud and rain of New Guinea, from an efficiency of, say, 40 percent to 70 percent.29

The same influence from above brought a drastic streamlining of Wanamaker’s transportation office, effective 1 June 1944. In essence, the change involved the wiping out of the previous organization by type of transportation (water, rail, highway, and air, with supporting administrative units), and the reorganization of the transportation office along functional lines (planning, administration, operations, and engineering). Any advantage that might have accrued from the functional approach must have been offset by time lost in reshuffling personnel and functions. In any event, the new order did not last. By the end of the year the new branches had been replaced by a divisional arrangement similar to the system previously in effect. (Chart 6)

Meanwhile, Colonel Wanamaker and his men had begun the long trek from Australia by way of New Guinea to the Philippines. The rear echelon officially closed at Brisbane on 20 September 1944, and by 8 October the entire Transportation Corps headquarters had moved to Hollandia, New Guinea. Late in November 1944, Transportation Corps and other USASOS personnel began to trickle into Tacloban, Leyte. By mid-April 1945

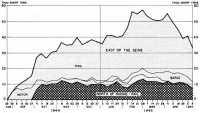

6: Organization of Headquarters, Transportation Corps, USASOS, SWPA: December 1944

Source: OCT HB Monograph 31, James R. Masterson, U. S. Army Transportation in the Southwest Pacific Area, 1941-1947, App. 5.

Wanamaker’s staff had set up offices in the Far Eastern University at Manila.

Throughout his tenure as Chief Transportation Officer, USASOS, Wanamaker headed a comparatively small service. Available figures, by no means satisfactory, indicate that the Transportation Corps personnel, both military and civilian, did not exceed 40,000 until February 1945 and reached their peak of almost 97,000 in the following September, when the war had ended in the Pacific. The civilian component was always considerable, approximately one third of all Transportation Corps personnel in SWPA.30

Wanamaker’s staff was responsible for only part of the U.S. Army transportation load in the theater. Organic transport assigned to the various combat and service units carried a major portion, including virtually all short hauls by motor vehicles. The bulk of the burden naturally fell upon the base commanders whose personnel operated under the technical supervision of the transportation office.31

Beginning with the operations in New Guinea, the theater developed a pattern for establishing new bases and arranging for supply and transportation. In each of the succeeding island campaigns, USA-SOS rendered logistical support, but did not bear responsibility for initial transportation, supply, and base development in the areas forward of its advance bases. Shipping for the movement of assault and supporting forces and for resupply was controlled by the Allied Naval Forces until such time as it was relieved by USASOS. Service and supply functions ashore were at first the responsibility of the ground task force commander, and all service troops assigned were under his command. After the area was secured and where conditions warranted it, USASOS took over the responsibility for these activities from the task force commander and established an advance base. Any elements and functions left behind by the task force in moving on to a new mission were assigned to the base commander. The latter had his own transportation staff, and except for technical supervision he was independent of the Chief Transportation Officer, USASOS.32

The autonomy of the base commanders, perhaps inevitable in a theater where bases and headquarters were so widely separated, was no more disturbing to Wanamaker than the pervasive control of shipping developed by the chief regulating officer. Some duplication and confusion arose as between CREGO and the USASOS transportation office in the issuance of orders for ship movements, and in Wanamaker’s judgment CREGO’s regulation was so detailed as to infringe on USASOS operating responsibilities. He argued that either USASOS should operate, under general staff direction from GHQ, or that GHQ should have a chief of transportation and operate all transportation directly.33 Neither alternative was adopted.

Under these circumstances the Chief Transportation Officer, USASOS,

obviously functioned in a severely restricted sphere. By 23 February 1945 Wana-maker’s dissatisfaction with his situation had reached the point where he requested immediate reassignment to the Corps of Engineers. Transportation activity in SWPA, he said, seemed “destined to be run by several Colonels in several echelons of command.” In ETO the chief of transportation was a major general, although his problems were neither more intricate nor involved than those facing Wana-maker. Despite all talk of the importance of his task, the Chief Transportation Officer, USASOS, felt keenly “the difficulties and discouragements in trying to get things done as just another Colonel.” As a matter of fact, General Frink had already recommended a promotion for Colonel Wanamaker, who finally was made a brigadier general on 6 June 1945.

Other observers shared Wanamaker’s dissatisfaction. In Washington Generals Somervell and Gross both felt very strongly that transportation activities in SWPA would never function efficiently until there was “one Chief of Transportation, speaking with the authority of the theater commander on transportation matters.”34 A long step was taken in that direction in June 1945 when General Somervell’s former chief of staff, General Styer, was appointed to head AFWESPAC so as to furnish logistic support for the invasion of the Japanese homeland. Somervell urged Styer to organize AFWESPAC in such a way as to give his chief of transportation the necessary authority to coordinate and control transportation activities from the theater level, by wearing two hats if necessary.35

General Wanamaker was succeeded on 23 July 1945 by General Stewart, an experienced transportation officer who had previously served with distinction in North Africa, Italy, and France. After his arrival at Manila, Stewart spent a month in diligent study in order to understand the prevailing cumbersome and involved supply and transportation system in SWPA. He was not pleased with what he found. Control of transportation was dispersed, and in his opinion the results were not good. The Transportation Corps, he said, had been browbeaten and held down by curbs on its authority and responsibility. Its personnel were timid, and they lacked pride, leadership, and initiative.

As Chief of Transportation, AFWES-PAC, and with the support of General Styer, Stewart at once adopted an aggressive attitude with a view to raising the prestige and strengthening the position of his office. He made considerable progress along these lines, particularly in the field of water transportation. Shortly after the end of hostilities, the GHQ regulating system was abolished and most of its functions were turned over to Stewart’s organization. This change, which was incident to the regrouping of U.S. and Australian forces into separate commands and the emergence of GHQ as a predominantly U.S. Army organization, was regarded by Stewart as “a great victory for the Transportation Corps.” In any event, in the period of demobilization and postwar adjustment the chief of transportation occupied a far stronger and more authoritative position in the theater than he had enjoyed during the wartime period.36

The Regulating System

As a U.S. Army organization functioning under USASOS during the wartime period, the Transportation Corps was but one of several transportation agencies operating in the Allied SWPA theater. The U.S. Navy, the Air Forces, the Air Transport Command, and the Australian military services were all operators and users. In view of the limited amount of available shipping and other transport, the even more limited receiving capacity of most of the ports, and the multiplicity of customers, there was a need to regulate on a priority basis all cargo and troop movements, regardless of service or nationality. After attempts to cope with the problem at various echelons in the theater, the task was assigned to a GHQ agency, CREGO, in November 1943.

The need of centralized control of military traffic had become apparent as soon as the first Americans landed in Australia. At the outset the coordination of American and Australian traffic was accomplished by a Movements Subcommittee of the Administrative Planning Committee, which had been established by the Australian War Cabinet in early January 1942 to facilitate inter-Allied cooperation. The subcommittee, which included both Americans and Australians, was headed by Sir Thomas Gordon, the Australian representative of the British Ministry of War Transport. The Administrative Planning Committee determined where incoming personnel and goods would be sent, and the Movements Subcommittee determined schedules and routes and allocated carriers. These arrangements were especially helpful to the U.S. Army in coordinating shipping and transportation during the first quarter of 1942, until the creation of GHQ SWPA, provided new machinery for Allied collaboration.37

Under USAFIA, the chief of Transportation Service and his representatives became responsible, in mid-April 1942, for all U.S. Army liaison with Australian transportation agencies. Such liaison was concerned primarily with incoming American vessels, which after clearance by the Royal Australian Navy were routed into the port selected by the U.S. Army for discharge. The G-3 of USAFIA prepared the troop movement directives and the G-4 was responsible for the shipment of supplies. Questions of priority of transportation involving only American troops or materiel were settled in conference between G-3 and G-4, USAFIA.

American and Australian forces both utilized the same slender resources in water transport. With a chronic shortage of tonnage, priorities had to be established. Initially, the decision as to which troops or cargo should move first was reached through informal negotiation between the Transportation Service and G-3 and G-4 of USAFIA, with final recourse if need be to G-3 and G-4 of GHQ SWPA.38

As military operations expanded in New Guinea, there developed a growing need of a more formal theater organization to control traffic. On 13 September 1942 a joint G-3/G-4 movement control office was established in Headquarters, USA-SOS, to handle all priorities for personnel and supply movements within the theater and to supervise the assignment of service units. After USAFFE was reactivated in

late February 1943, the coordination of troop and cargo movements was assigned to the executive for Supply and Transportation in USASOS,39 subject to the supervision of USAFFE. On 20 June 1943 a USAFFE movement priority system was established, nominally in the Office of the Chief of Transportation, USAFFE, to determine and supervise priorities of U.S. Army troop and supply movements in SWPA. In addition to a central office, branch priorities offices were organized in Headquarters, USASOS, and at each USASOS port headquarters.

Early in the following month Lt. Col. (later Col.) H. Bennett Whipple was designated Chief Movement Priority Officer, USAFFE, under G-4, USAFFE. At the same time twelve USAFFE movement priority officers (including three Transportation Corps officers) were named to determine priorities locally, in addition to their supply and troop movement duties. When the Office of the Chief of Transportation, USAFFE, was discontinued in September 1943, the USAFFE movement priority system was retained in USAFFE under G-4.

Stirred by his own experience as a movement priority officer, Colonel Whipple became an ardent advocate of a GHQ regulating system.40 His views were set forth in a detailed memorandum of 22 August 1943, which described a current situation at Port Moresby. There, twelve ships already were in the harbor, many more were due to arrive, and conflicting demands on the limited port facilities were rampant. Everything was top priority. Using Port Moresby as a typical example, Colonel Whipple argued that traffic regulation in SWPA should be made a GHQ and not a USAFFE function, since Allied Land, Air, and Naval Forces, and not merely U.S. Army Forces, were involved. Deciding among these competing “customers” generally required information that the local operators did not have and only GHQ SWPA, was likely to possess. The proposed regulating system was also to include air shipments, for which there existed no over-all booking and priority organization. In short, in the light of his broad knowledge of the supply and shipping situation and the combat plans, the chief regulating officer was to determine the priority of all movements.

The Establishment of the GHQ Regulating System

Colonel Whipple’s recommendation met with approval, and on 12 November 1943 a GHQ regulating system was established under the direction of a chief regulating officer, Col. Charles H. Unger. His functions were to assign priorities to individuals, troops, organizational equipment, and cargo for water, air, and rail movement and to coordinate schedules, except for combat vessels and aircraft; to establish direct contact with supply, transportation, and other similar agencies as required; and to issue detailed instructions to implement the regulating system. Whipple became Colonel Unger’s executive officer and the principal proponent of the new system. The headquarters organization included two former Transportation Corps officers: Lt. Col. Charles A. Miller, chief of the Water Section, and Lt. Col. Thomas F. Ryan, chief of the Air Section. The staff for CREGO was drawn chiefly from the

U.S. Army, but it also included personnel of the U.S. Navy and the Australian armed services. The entire regulating system depended upon direct communication with all agencies and elements in the theater, without which the whole structure would have been ineffectual.

Regulating system procedures, set up on a tentative basis immediately following the establishment of CREGO, were worked out in detail and issued by CREGO during January 1944.41 The instructions covered all air, water, and rail movements to, within, and from the theater, except those by small ships assigned to local commanders and, as already indicated, combat vessels and aircraft.

For water transportation within SWPA, G-3 at GHQ determined priorities for troop movements, while G-4 set those for special cargo movements. CREGO set up these movements in the priorities indicated, directly established priorities on requests for the assignment of shipload lots, and arranged for the movement of individuals or small detachments on available shipping space. The priority of other water cargo movements was determined by the local regulating officer at the destination point. The tool for making these decisions was the weekly consolidated booking list. Prepared at the point of origin by the local transportation officer, the list included all cargo movement requests of the commands being served, all booked cargo remaining unshipped, and the relative priority of movement desired by the commands. The list was then turned over to the point of origin regulating officer or, if movement originated on the Australian mainland, directly to CREGO. It was then transmitted to the regulating officer at destination, who, in consultation with the operating and receiving agencies involved, used the list as the basis for determining the priority of movement. The loading-point regulating officer also provided the regulating officer at destination with information regarding ships loading out for, and those awaiting call forward to, their ports. Based on the local port situation and the recommendations of the local commander or on instructions from CREGO, the destination regulating officer called forward, through the local naval officer in charge (NOIC), ships reported as ready for call to his port. The release of the ships for forward movement was arranged for by the regulating officer at the loading port through the local NOIC. Actual loading of cargo and operation of vessels was performed by the commands that operated transportation.

Intra-SWPA cargo shipments by water were classified according to four priorities, lettered from “B” to “E,” in descending order of importance. To expedite such movements, commands operating transportation were to reserve until thirty-six hours before departure 2 percent of cargo space for high-priority items. All priority cargo was to be moved as rapidly as possible, even if items in two or more priority classifications had to be moved simultaneously.

Provisions for the regulation of intra-theater air movements were similar to those for water movements. Since all air traffic was emergency or special in character, priority classifications were set up according to degree of urgency. Five classifications were used to cover priorities

for movements varying in urgency from immediate precedence to ninety-six hours.

So far as rail movements were concerned, CREGO was to assign priorities for movements of special interest to GHQ and to prescribe procedures for priority movements where regulating officers were not assigned. The regulating officer at Townsville was to establish local priorities on requests submitted by local commands and arrange for the transfer of GHQ priority movements to and from rail. In both cases, actual moves of troops and cargo were handled by the Australian Army’s movement control organization.

Transpacific air passenger and cargo traffic on aircraft allocated to SWPA was classified according to four priorities (Classes 1 through 4), set up in descending order of urgency. CREGO was to coordinate air transport requirements and available aircraft space, clear all priorities for movements to and from the United States and intermediate points, assign identification numbers to all priorities, and advise USAFFE and Seventh Fleet of changes in the availability of aircraft. He would maintain a liaison office at Hickam Field, Hawaii, and at such other terminals as necessary. The liaison officers would represent CREGO and act as advisers to commands operating air transport, and provide CREGO with information regarding actual and projected movements. The commands operating air transport were requested to make all shipments in accordance with assigned priorities and to provide CREGO with monthly estimates of available westbound tonnage, airway bills for all shipments, and passenger and cargo manifests upon arrival at the western terminal.

Provision was also made for CREGO to take over the functions pertaining to transpacific water movements previously exercised by the GHQ Priorities Division. CREGO assumed responsibility for clearing the assignment of special transpacific water cargo priorities. Special priority requisitions were to be submitted by USASOS and Fifth Air Force through USAFFE to CREGO, and directly from Seventh Fleet to CREGO.

From modest beginnings the GHQ regulating system developed into a huge completely centralized agency for the detailed control on a priority basis of troop and cargo movements in the Southwest Pacific Area. Functioning under the immediate supervision of the Deputy Chief of Staff, GHQ, the chief regulating officer sought to serve as an impartial referee among the various claimants for the limited transportation within the theater. The chief concern of CREGO was with transportation by air and by water, for which he built up an elaborate control organization. Branch regulating offices (later called stations) were created in the forward areas as the need arose. Through liaison officers the regulating system’s influence was ultimately extended far beyond the confines of SWPA. In connection with the regulation of transpacific air traffic, air liaison offices were established in February 1944 at Hickam Field, Hawaii, and Hamilton Field, California. In June 1944, CREGO assigned two liaison officers to the Headquarters, South Pacific Area (SPA), at Nouméa, New Caledonia, to regulate the flow of troops and their equipment from SPA into SWPA. In the following month a SWPA liaison group was set up at the San Francisco Port of Embarkation to advise as to the desired priorities for movement of SWPA cargo

and personnel and the approximate dates when specific shipping could be received at destination ports. Other liaison officers served at the convoy assembly point of Kossol Roads, in the Palaus, and at Guam.

CREGO moved his headquarters successively from Brisbane to Hollandia, then to Leyte and Manila. At the height of his activity, in mid-January 1945, the chief regulating officer had twenty-two branch regulating stations and liaison offices, sprawling over the Pacific from Australia to California. His headquarters staff, numbering about 150, directed the intra-theater traffic of approximately 500 noncombatant vessels and had access to the available space on about the same number of transport planes. Priorities were assigned in the light of the workload and capacity of each port, the vessels and airplanes available, and the relative urgency of the shipment. During 1944 CREGO arranged for the movement into the forward areas of approximately 110,000 troops per month with all vehicles and equipment and, in addition, one million measurement tons of supplies and equipment.

The chief regulating officer could not function successfully without a thorough up-to-date knowledge of the supply and transportation situation throughout the theater. He kept elaborate records on all matters pertaining to the personnel and cargo traffic under his jurisdiction. Direct contact between CREGO and his regulating and liaison officers was maintained around the clock by means of an excellent communications network, which made possible a steady flow of information, orders, and other operational and administrative data. The status of ports, ships, and movements was shown by entries on cards posted on large boards. These cards, which were kept current, were reproduced periodically by a photographic process, and copies were distributed to interested agencies.42 The system involved numerous records, all containing in substance the same information but compiled from various points of view. The most important data, however, concerned conditions at the destination port, which was always considered the bottleneck.

The GHQ regulating system in SWPA was, indeed, a far cry from the individual U.S. Army regulating station designed primarily for rail transport. The tremendous movement control organization developed by the chief regulating officer presented a tempting target for critics, who suspected that an unnecessary empire was being built. The system was vulnerable, for in determining the priority of movements as between powerful competing interests, CREGO almost inevitably aroused resentment. Among the interested agencies were USASOS, the Transportation Corps, and the Air Transport Command, each of which on occasion felt that its normal activity was hampered by interference from CREGO. With the demand for transportation usually greater than the supply, priority became all important and one or more would-be “customers” necessarily met with disappointment. Except during a brief period of outstanding cooperation when Colonel Plant was Chief Transportation Officer, USASOS, the struggle between the regulating system and the transportation office went on “pretty continuously.”43

The first big offensive against the regulating system was led by the commanding general of USASOS, General Frink. In a memorandum of 19 May 1944, addressed to General MacArthur, General Frink made the following charges. Under the prevailing arrangement the local base commanders had the last word in regard to the booking lists and so could in effect veto USASOS decisions, thereby interfering with the build-up of stocks for operational requirements. Local regulating officers might, and often did, try to run the ports, when their work should have been confined to refereeing conflicting requirements of the several U.S. and Allied forces. The regulating system encompassed the complete control of all vessels, amounting to virtual management of intratheater transportation. Specifically, Frink urged a relaxation of the centralized control exercised by CREGO and a periodic allotment to USASOS of tonnage available for cargo movement on a priority basis but accomplished with shipping scheduled by USASOS. GHQ SWPA, however, was unwilling to make any drastic change in the prevailing system, which it described as basically sound.

Although the regulating system emerged victorious from this encounter, it remained under almost constant attack throughout 1944. According to its most ardent advocate, Colonel Whipple, the main difficulty arose because CREGO was unable to sell his system to USASOS and G-4 of GHQ and to win their complete cooperation. Furthermore, in 1944 an increasingly serious congestion of shipping in SWPA drew heavy fire from the War Department, the Transportation Corps, and the War Shipping Administration, culminating in a stern call from Washington for drastic action in the theater to expedite the turn- around of the cargo vessels so desperately needed to fight a global war.

By its very nature, the regulating system often led to duplication and confusion. Within the theater no ships could sail from their loading ports without being cleared by instructions from CREGO. Such shipping instructions were issued simultaneously by CREGO to the Chief Transportation Officer, USASOS, and the local regulating officer. The latter, by virtue of his direct contact with CREGO, received instructions, and often also the changes, long before the USASOS data, which passed through command channels, reached the port. On occasion the base port commander was confronted by apparently conflicting instructions, which had to be reconciled by reference to USASOS headquarters and consultation with CREGO. Such instances obviously hindered efforts to coordinate ship movements efficiently, and undoubtedly strained relations between CREGO and USASOS.44

Still more disturbing for CREGO was the repeated tendency in USASOS to bypass the regulating system and to appeal directly to G-4, GHQ. From about July 1944, G-4, GHQ, built up its Transportation Section. The Transportation Section then began to relegate CREGO to a subordinate “bookkeeping agency,” which had to submit even the most minor action for final decision. According to Colonel Whipple, the belligerent attitude of USASOS and the aggressive stand of G-4 at GHQ in large measure represented a very human urge “to get into the act,” which was coupled with a burning desire

to control theater shipping.45 In his opinion, USASOS could have gained the same ends without confusion or turmoil by merely booking its cargo in the prescribed manner and applying for priorities, referring any conflicts to CREGO for settlement by G-4 at GHQ if so desired.46

The Problem of Shipping Congestion

Much of the heat and friction generated by this unwholesome situation might be dismissed simply as the byproduct of disagreement as to who should regulate and control traffic within the theater, but the matter unfortunately had wider and more serious ramifications. By autumn 1943 shipping congestion had already become a problem in SWPA. Despite strenuous efforts by CREGO to control the flow of shipping in accordance with supply requirements and the receiving capacity of destination ports, the immobilization of vessels in the theater assumed increasingly serious proportions.47

Congestion developed at Milne Bay, New Guinea, in September and October 1943. It came of routing more ships to the port there than could be promptly discharged and of holding other vessels until they could be called forward to Finschhafen. Later, in January 1944, the harbor at Milne Bay held as many as 140 ships, some of which had been there more than a month. During the first half of February, Milne Bay had the lowest average discharge-261 measurement tons—per vessel per day of any port in SWPA. Seven of the vessels awaiting discharge at the end of this period had been in port for forty days or more. The War Department demanded immediate corrective action. Although the theater tried to comply by expediting cargo discharge, the congestion continued.

Similar difficulties were encountered, successively, at Hollandia, Leyte, and Manila. At each forward base, cargo discharge generally was slowed by the lack of port facilities, a shortage of labor, a shortage of trucks, mud, rain, and enemy air raids. Under these circumstances, with storage space ashore limited or almost nonexistent, the natural tendency in the theater was to use Liberty ships as floating warehouses and to meet the most urgent requirements by means of selective discharge. As a result, vessels in increasing numbers lay idle, the scarcity of bottoms became more acute, and drastic expedients ultimately had to be adopted in order to bring relief.

Aware of the growing congestion, the chief regulating officer unsuccessfully attempted to obtain satisfactory corrective action, by which he meant the retarding of

scheduled loadings. His office reported on 18 October 1944 that there were 87 ships at Hollandia-12 discharging, 3 loading, 24 awaiting call to Leyte, 33 waiting to discharge, 5 waiting to load, and 10 miscellaneous. Of the 45 ships discharging or waiting to discharge, 7 were troop transports and 38 were cargo ships, of which only 9 had been scheduled for Hollandia by CREGO. The remaining 29 evidently had come directly from the zone of interior. These last 29 shiploads could just as well have remained in the United States, because they were no closer to being in the hands of combat troops than if they had been held in San Francisco and loaded at a time that would have permitted immediate discharge on arrival at Hollandia.

The invasion of Leyte in late October 1944 brought further difficulty. Major changes in operational plans calculated by the theater commander to speed up the campaign in the Philippines created unanticipated requirements. The effort to meet these needs, together with delays in cargo discharge caused by the elements and enemy action, resulted in a large accumulation of vessels at Leyte. Meanwhile, despite some improvement at Hollandia, a major supporting base, too many freighters were still being held entirely too long. Thoroughly alarmed, CREGO again attempted to arrange for a cutback in scheduled loadings, notifying G-4, GHQ, on 11 November that information on hand indicated that by early January 1945 approximately 100 vessels would be idle awaiting discharge or call forward to Leyte. No action was taken, and the shipping tie-up materialized as predicted. According to Colonel Whipple, both G-4, GHQ, and USASOS realized the situation but appeared unable to resist pressure from various agencies to “load out more and more items and more and more ships” for Leyte; apparently the supply people “found some security in having their supply backlogs on ships” even though the vessels might not be discharged for some time to come.48 As for the theater commander, he believed that the speedup of the campaign had justified the expense in shipping.49

The tie-up of shipping at Hollandia and Leyte finally led to drastic action in late November 1944 by the President acting through the Joint Chiefs of Staff. The theater was notified that from May through October 1944, inclusive, a total of 270 ships had been loaded and sent out, of which 177 were completely discharged. Only 98 of the latter had been released for return to the zone of interior. Vessel retentions had swollen from 112 on 15 May to 190 on 11 November, and the theater commander was therefore ordered to release at once at least 20 vessels in this category. He was not to exceed 170 retentions at any time during December 1944, and he was asked to report the number of additional vessels to be released for return to the United States by the end of January 1945. Further, the planned sailings from the west coast to SWPA during December 1944 were to be reduced arbitrarily from 40 to 30 ships.

In view of the growing port and shipping congestion in the Philippines, the War Department, on 8 December 1944, notified the theater commander that only two courses of action seemed open: (1) reduction of vessel retentions from 170 on 20 December 1944 to 100 by 15 January

1945; and (2) elimination, where practicable, of U.S. sailings for SWPA in December and in January 1945. The War Department called for “immediate drastic action.” General MacArthur asked to have the proposed reduction postponed for two months because of the impending invasion of Luzon, but before his reply could reach Washington, where patience had worn thin, the Joint Chiefs of Staff had already directed all theater commanders to cease using ships as floating warehouses, to reduce sailing schedules to conform to port discharge capacities, to discontinue selective discharge except for urgent operations, and to submit detailed reports on the position and employment of ships.

General MacArthur again protested, but to no avail. He also sent a representative, Brig. Gen. Harold E. Eastwood, to Washington to urge reconsideration of the cut in shipping to SWPA. General Eastwood felt that the War Department was hostile to SWPA while other theaters grew fat at its expense. General Wylie, Assistant Chief of Transportation for Operations, regretted this misconception and pointed to the fact that ETO, the top-priority theater, had suffered far deeper proportionate cuts in shipping than had as yet been applied against SWPA.

General Wylie believed that the theater had consistently leaned far over on the safe side in setting up its supplies and in loading for operations on the basis of “too early and too much.”50 There had been no realistic appreciation of discharge capacity and no inclination to reduce requirements once it had become apparent that optimistic forecasts would not be met. Later, in June 1945, a study of Pacific supply, based on data from San Francisco Port of Embarkation, disclosed that SWPA had “consistently requisitioned tonnages in excess of ability to receive and unload,” and that a total of 750,000 tons of cargo was awaiting shipment from the west coast to SWPA. According to Colonel Whipple, USASOS had built up a tremendous backlog of cargo in San Francisco despite repeated objections by CREGO that fell upon deaf ears in G-4 of GHQ.51

In SWPA, as in ETO, efficient utilization of shipping had obviously been made secondary to a comfortable supply position. Transportation Corps officers in Washington, however, felt that the operations in SWPA could be supported without an excessive floating reserve of idle vessels. None of General Eastwood’s comments, said General Wylie, could excuse ships lying at anchor 40, 50, and 60 days awaiting discharge. This firm stand had a salutary effect upon SWPA, which at long last sought to adjust shipping requests to the approximate discharge rates.

Experience with confusion and congestion at Milne Bay, Hollandia, and Leyte by no means prevented similar conditions at Manila. General Wylie, who visited that port in the spring of 1945, found that USASOS, in dealing with G-4, GHQ, often bypassed the chief transportation officer as well as CREGO. General MacArthur personally accepted full blame for any shipping congestion, for he believed that getting into Manila at an early date justified some logistic difficulties. What he did not mention, said Wylie, was that his staff had been slow to adjust the shipping requirements to the changed target dates. As a result, the War Department had to

make arbitrary cuts in tonnage, action that might better have been taken by the theater in light of its own needs and capabilities.52

In fairness to SWPA, it should be pointed out that the port facilities at Manila had suffered severely from wartime damage and destruction, with a resultant adverse effect upon the rate of cargo discharge. A shortage of trucks and labor at the dumps hampered port clearance. However, the worst congestion came in the late summer and early fall of 1945, when ships arrived from the United States and Europe but could not be unloaded because of the scrambled situation after the surrender of Japan. The subsequent outloading of forces for occupation duties and demobilization further complicated the picture.

The Disbandment of CREGO

Following the end of hostilities, the theater took steps to dismantle the GHQ regulating system. Effective 31 August 1945 the CREGO organization was formally disbanded. Priority controls over water traffic were transferred to AFWESPAC, but GHQ SWPA, retained the function of establishing and implementing air priorities.53 Among the CREGO functions assumed by AFWESPAC as of 1 September were: (1) control of “intra-area water movements of Army personnel and cargo except movements made in assault shipping”; (2) preparation and submission of ACTREPs (activity reports) and PACTREPs (Pacific activity reports); (3) preparation and distribution of a “consolidated daily port status report”; (4) routing of intra-area vessels assigned to AFWESPAC, of transpacific vessels destined for ports under the control of AFWESPAC, and of such other vessels as might be assigned by GHQ AFPAC; and (5) assignment and publication of SWPA and local numbers of all Army-allocated and Navy-allocated vessels in the area. Movements of assault shipping and assignment and release of vessels from the local fleet continued to be as directed by GHQ.

As already indicated, the newly appointed Chief of Transportation, AFWESPAC, General Stewart, regarded this transfer as a triumph for the Transportation Corps. But irrespective of the aggressive stand taken by Stewart, the end of the war against Japan and the ultimate regrouping of the Allied forces in SWPA into separate independent commands undoubtedly would have led to the abandonment of the GHQ regulating system. The reversion of SWPA from an Allied headquarters to one predominantly U.S. Army in make-up made logical a shift of regulating responsibilities from the Allied GHQ level to AFWESPAC.54

While it functioned, the GHQ regulating system all too often provided a convenient scapegoat for the frequent failures to tie in transportation and supply within the theater. The chief regulating officer undoubtedly took the blame for many conditions beyond his control, such as inadequate port facilities and unexpected demands created by changes in tactical plans. Accusations and countercharges tended to obscure substantial achievement attained in the priority control of theater traffic. Like many another referee, CREGO discovered that his decisions

were not always cheered. The maze of controls, regulations, and reports was forbidding, particularly for the transportation operator who felt that he could direct his own traffic.

The chief regulating officer had neither a perfect nor an infallible system. Given the same handicaps, another agency might or might not have done the job with fewer headaches. Even the critics of the regulating system, such as Generals Frink and Wanamaker, conceded that the control of Allied traffic on a priority basis was necessary. The problem was to determine the proper place and scope of the control mechanism within the theater organization.

According to Frink, the regulating system would have worked better in SWPA had GHQ been content simply to allot tonnages to the various forces involved and left the regulating function to his chief of transportation. As it was, he believed that CREGO attempted to exercise a much too detailed control over the movement of ships, personnel, and cargo.55 On the other hand, CREGO found that he lacked the necessary authority and support to do a fully effective job. Apparently with the encouragement of some staff members of G-4, GHQ USASOS in many instances circumvented CREGO directives. Moreover the G-4 Transportation Section, which was actually duplicative in function, increasingly dominated CREGO from the summer of 1944 onward.

The division of transportation responsibilities and functions as between the GHQ G-4 Transportation Section, CREGO, and the Chief Transportation Officer, USASOS, almost inevitably led to misunderstandings, clashes, and some duplication.56 Colonel Whipple, who had been instrumental in the establishment of the regulating system and the guiding spirit behind it, believed that better results would have been attained if the control of all transportation and regulation had been placed in the hands of one officer, responsible only to the Chief of Staff, GHQ. Located in the Allied headquarters and utilizing all port facilities, ships, railways, and transport aircraft, including the necessary personnel, this officer would meet the requirements of G-3 and G-4, referring to the chief of staff any conflicts that could not be settled by conference. Such a system, if supported by all concerned, he contended, would have eliminated much of the difficulty encountered.57

The U.S. Army Fleet in SWPA

From beginning to end the war in the Southwest Pacific was highly dependent upon movement by water. Almost all American support in men and material had to be sent by ship from the United States, a distance of approximately 6,000 nautical miles. Within SWPA the bulk of wartime traffic was by sea, from island to island and along the coastal fringes of the larger land masses.

The shipping that supported the U.S. Army in SWPA consisted of ocean-going vessels moving back and forth between the United States and the theater, and vessels

used solely within the theater. Ships normally engaged in transpacific runs might be retained for temporary service in SWPA, and while so employed they were in effect part of the local fleet. Within SWPA all shipping was under the control of the Allied theater commander.

Fortunately, except for a brief period before and after Pearl Harbor, ocean traffic to and from the Southwest Pacific was unhampered by the convoy system, which of necessity obtained in the Atlantic and Mediterranean areas. In October 1941, because of growing concern over possible hazardous conditions in the Pacific, the U.S. Navy recommended that all troop transports, as well as freighters carrying valuable military cargo such as airplanes and tanks, be convoyed between Honolulu and Manila. The Army acquiesced, and thereafter the required escorts and routing were furnished by the Navy. The Navy announced on 26 December 1941 that it could not escort more than one fast troop convoy to Australia per month and that all slow cargo ships bound for that area would simply be “turned loose to proceed individually.”58

The policy of protecting only the troop transports and letting the cargo vessels fend for themselves was agreeable to General Somervell, who was willing to accept the risk of loss at sea in order to move urgently needed supplies to the Far East. In the first few months of the war providing escorts proved troublesome. The Army generally was impatient of the delay in setting up convoys, and the Navy was reluctant to carry troops in vessels with a speed of less than 15 knots. Luckily, enemy submarine activity never became serious in the Southwest Pacific. From the fall of 1942 on, troop and cargo ships usually traveled without escort, except in the forward areas where naval and air protection had to be given.59

Like the other Pacific areas, SWPA experienced an urgent need for ships because of its utter dependence upon water transport. The world-wide shortage of bottoms precluded full compliance with SWPA requests, and until V-E Day the shipping needs of the war in Europe took priority over those of the conflict with Japan. In Australia, as in the United Kingdom, local resources were exploited as fully as possible so as to reduce shipping requirements. An unexpected but welcome source of supply for SWPA was the “distress cargo” from sixty-one American, British, and Dutch ships that had taken refuge in Australian ports during the early months of the war.

Ocean-Going Vessels in Intratheater Service

With ocean shipping short everywhere and Australian tonnage already depleted by two years of war, the U.S. Army had difficulty in assembling a local fleet for intratheater use.60 The initial acquisitions for this purpose were effected by purchase or charter from private owners, but thereafter new construction provided the principal source of supply. Vessels of Australian registry were procured through Sir Thomas Gordon, director of shipping for the Australian Commonwealth. American flag vessels and available ships of other flags were obtained by the War Department through the War Shipping

Administration, which had its representatives in Australia.61

After Pearl Harbor the theater, under desperate pressure to supply the Philippines and Java, had been forced to seize every ship within reach. Enemy action resulted in severe losses, notably at Darwin where Japanese bombers destroyed almost all the shipping in the harbor, including the veteran Army transport Meigs. In mid-March 1942 the USAFIA local fleet totaled only seven vessels: three U.S. craft, one Philippine ship, and three small vessels belonging to the British-controlled China Navigation Company.

With the fall of Java and the impending loss of the Philippines, Australia became the main base of operations in the Southwest Pacific. A local fleet was therefore essential in order to move personnel, equipment, and supplies from the Australian ports to the forward areas. The first substantial increment for this fleet came in the spring of 1942, when 21 small vessels were obtained by charter from the Koninklijke Paketvaart Maatschappij (KPM). Known as KPM vessels, the ships had formerly operated in the Netherlands East Indies. Loaded with refugees, they had limped into the nearest Australian ports to avoid capture by the Japanese.62

Large ships generally were obtained by retention of WSA vessels dispatched to SWPA from the zone of interior. Since such ships were retained only for temporary assignments, the theater had to secure other vessels that could be kept for a longer time in a so-called permanent local fleet. Beginning in the summer of 1942, SWPA repeatedly requested additional vessels, large and small, that could be used for intratheater missions. Initially, the theater demanded at least twenty ships of the “Laker” type,63 which were of moderate draft and had large hatches. That number, minus one sunk en route, was procured ship by ship in the United States, and delivered to the theater by the Transportation Corps. The first Laker, City of Fort Worth, reached SWPA on 12 March 1943, and the others arrived at various dates thereafter. These vessels were generally about 251 feet long, of approximately 2,600 gross tons, and had a speed of 8 to 9 knots. They were supplemented by a dozen other vessels, somewhat larger but with similar characteristics.

The Lakers had seen hard service for twenty years or more, and all required considerable reconditioning before being sent across the Pacific. Originally designed for short voyages, they had limited water and fuel capacity. After a year of experience with these vessels, Colonel Plant, Chief Transportation Officer, USASOS, reported that they were “a constant repair problem” and had been “very much of a headache.” Yet unsatisfactory as these ships were, the theater could not have done without them.

Indeed, to meet the ever-urgent demand for intratheater shipping, an additional assortment of ocean-going vessels,

ranging from 200 to 400 feet in length, was acquired from private owners. Of both American and foreign registry, these ships became part of the local SWPA fleet, which by December 1943 totaled 52 vessels, varying in speed from 8 to 16 knots. At that time one KPM ship, the Maetsuycker, had been converted into a hospital ship, ten vessels were employed as troop carriers, and the remaining forty-one served as freighters.64

From the very beginning the slow but versatile “work-horse of the sea,” the EC-2 Liberty ship, was included in the local fleet. Ultimately, most of the Liberties in intratheater traffic consisted of vessels temporarily withdrawn from transpacific runs, a practice that had been authorized on an emergency basis as early as mid-February 1942. To the dismay of the War Shipping Administration and the Transportation Corps at Washington, the theater’s appetite for such retentions grew and grew until it finally had to be curbed.65

The theater found Liberty ships very useful as cargo carriers because of their large hatches and deep ‘tween decks and lower holds. These vessels also gave good service as emergency troopships. Under the direction of Colonel Plant, in the fall of 1942 Liberty ships were converted overnight into troopers to meet a pressing need for that type of transport for operations in New Guinea. Field kitchens, protected by shelters made of dunnage, were placed on the port side between numbers two and three hatches. Trough latrines were installed on both sides on the after deck between numbers four and five hatches. They were flushed by lengths of hose connected to the fire hydrants. A few fresh water outlets were added at each end of the amidships house. No standee bunks were installed, and the ‘tween decks were kept clear of all cargo. Usually, both officers and men slept on the deck in good weather. Normally, each ship carried 900 troops. These conversions provided the necessities such as lifesaving equipment but no frills, and the ships could be quickly reconverted into freighters when so needed. Division commanders later told Plant that the passage on a Liberty troopship served well as preparation for the hardships that lay ahead.66

Liberty ships, while highly desirable for ocean voyages between Australia and New Guinea, were too large for coastal service in shallow and uncharted waters. Accordingly, early in 1943 the theater urged the development and standardization of a medium-size vessel, 250 to 300 feet long, with adequate cargo gear, large hatches, refrigeration, and a speed of around 14 knots. At least 200 ships with these specifications were desired for intra-theater supply missions. They were needed to expedite deliveries, to minimize transshipment delays, and to avoid possible loss of large vessels in the poorly charted and frequently hazardous waters of the forward areas.

All told, in June 1943 the theater requested a total of 420 vessels of various types, a requirement deemed “excessive” by the Office of the Chief of Transportation at Washington. Although that demand could not be met, the theater’s vessel requirements were partially filled by

the continued procurement of older vessels. Lacking enough ships for local assignments, the theater relied increasingly on the temporary retention of WSA vessels. Relief came in 1944 with the construction by the U.S. Maritime Commission of three types of vessels that were especially suited for service in SWPA—C1-M-AV1 vessels, Baltic coasters, and concrete storage-ships.

The C1-M-AV1, a steel cargo vessel of 3,805 gross tons, diesel powered, with a length of approximately 339 feet and a speed of 11 knots, became the answer to the theater’s request for 200 craft of medium size. Production difficulties delayed deliveries of the C1-M-AV1 type to the theater. Bearing such salty names as Clove Hitch, Star Knot, and Sailor’s Splice, these ships began to reach SWPA in limited numbers in February 1945. The C1-M-AV1’s were satisfactory, and their earlier availability might have made unnecessary the employment of the old Lakers, which were costly to convert, maintain, and repair.

As partial substitutes for C 1-M-AV1’s, the theater requisitioned fifteen Baltic coasters on 16 March 1944. The Baltic coasters delivered to SWPA were oilfired cargo ships of 1,791 gross tons, with a length of approximately 259 feet and a draft when loaded of almost 18 feet. These vessels were well adapted for operations in the shallow waters of New Guinea. The Baltic coasters began arriving in September 1944, in time for the landings on Leyte.

Much less desirable than the Baltic coasters were the concrete vessels, which began to anchor in the theater in late November 1944. Described as Type C1-S-D1, they were of 4,826 gross tons, with an approximate length of 367 feet and a speed of 7 knots. Because of known deficiencies, such as seepage through the porous concrete bulkheads of the fuel and water tanks, these ships were employed solely as floating warehouses.

The local ocean-going fleet in SWPA increased by almost one half between 15 July 1944 and 24 January 1945, but it remained almost stationary in size thereafter. By 1 August 1945 the proportion of these vessels built in the United States for use in World War II had increased to about 54 percent as compared with about 3 percent on 15 July 1944. The following tabulation indicates the change in the composition of the local fleet between 1 December 1943 and 1 August 1945:67

| Type of Vessel | 1 Dec 43 | 15 Jul 44 | 21 Jan 45 | 9 May 45 | 1 Aug 45 |

| Total | 52 | 64 | 93 | 94 | 98 |

| KPM | 21 | 22 | 19 | 13 | 9 |

| China Nav. Co | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Lakers | 17 | 26 | 25 | 21 | 19 |

| Other private | 7 | 11 | 17 | 16 | 14 |

| Liberties | 4 | 2 | 11 | 8 | 5 |

| Baltic coasters | 0 | 0 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| Concrete | 0 | 0 | 4 | 9 | 14 |

| C1-M-AV1’s | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 18 |