Chapter 19: Iwo Jima

After V-J Day many Japanese leaders professed to have seen in their loss of the Marianas a turning point in the war. They knew of the B-29 and they correctly surmised that the islands had been seized chiefly to serve as VHB bases. Prince Higashikuni, Commander in Chief of Home Defense Headquarters, testified:–

The war was lost when the Marianas were taken away from Japan and when we heard the B-29’s were coming out. ... We had nothing in Japan that we could use against such a weapon. From the point of view of the Home Defense Command, we felt that the war was lost and said so. If the B-29’s could come over Japan, there was nothing that could be done.1

This appraisal was to prove accurate enough in the long view, but in February 1945 combat crews might have been surprised to learn that a responsible Japanese officer had conceded defeat. Of the ultimate success of the VHB mission they were confident, but so far bombardment results had been less than spectacular and losses had been heavy. Superforts had been destroyed on their bases by enemy intruders; others, in spite of the prince’s rhetoric, had been shot down from the skies over Honshu; still others, wounded or bothered by mechanical difficulties, had crashed or ditched during the long flight over unfriendly waters. Both Hansell and LeMay had worked to insure a better air defense of their island bases, to improve the defensive tactics of bomber formations over Japan, to reduce operational losses on missions, and to provide better rescue services for crews forced down at sea. There was no single solution for any of these problems, but the one factor common to all was Iwo Jima, an ugly bit of volcanic rock directly astride of, and about midway along, the route from Isley Field to Tokyo. In Japanese hands the island was a menace to B-29’s on the ground at Saipan bases, an obstacle to formations headed for

Tokyo, a threat to air-sea rescue services. In American hands Iwo would provide a site for navigational aids, an emergency landing field for B-29’s in distress, a staging field for northbound planes, a base for fighter escorts, a station for rescue activities.

Iwo Jima was secured on 26 March 1945 after a bloody campaign which has been called by a Marine historian “the classical amphibious assault of recorded history.”2 The assault was largely the work of V Amphibious Corps and a Navy task force, but the operation, like the capture of the Marianas, was primarily for the benefit of the B-29’s. Since the XXI Bomber Command took some part in the campaign and Army Air Forces, Pacific Ocean Areas (AAFPOA) expended much of its bombardment effort against the island during the autumn and winter, it is pertinent to describe here the conditions which made the capture of Iwo Jima seem necessary, the campaign itself, and the development of the island into a VHB base.

Defense of the Marianas

With the seizure of the Marianas, U.S. forces had thrust deep into enemy territory. From bases in those islands air power could bring the industrial cities of Japan under sustained attack and harry the routes by which the enemy still sustained forces in the outlying islands. The Marianas operation was a product of the decision at Cairo to shorten the war against Japan; like most short cuts, it involved certain risks which had been deliberately accepted.

Those risks, as they appeared in the summer of 1944 when Saipan, Tinian, and Guam had been secured, were from enemy air – it was unthinkable that the Japanese could retake the islands they had been unable to hold. If the Japanese had no bombers which could match the B-29 in range, they still held island bases from which conventional aircraft could strike at the Marianas. Bypassed Truk lay less than 600 miles to the rear. Farther back the Japs held positions in the Gilbert-Marshall area. Athwart the great circle route from Hawaii to Saipan was Wake Island. Within a radius of less than 400 miles were Woleai, southward, with a landing field and seaplane base, and Yap, southwestward, an important staging point on the Truk-Philippines route. Nearby, the lesser Marianas were still in enemy hands, and though most of those islets served only as a refuge for Japanese soldiers escaping from the major islands, two, Rota and Pagan, boasted airstrips. Northward was the Nampo Shoto, a long chain of scattered islands

stretching from the 24th parallel to the lower coast of Honshu, with subgroups known to Westerners as the Bonin and the Volcano islands. The Bonins owed their name to a corruption of a Japanese term meaning “empty of men,” but the name was no longer accurate. Chichi Jima had an airstrip and a large harbor; Haha Jima had two good harbors; and Iwo Jima, a comparatively recent addition to the Volcano group, had two operational airfields with double runways and a third, with a single strip, under construction. On occasion, as many as 175 planes had been counted on these fields,3 which were only 725 miles from Saipan – well within tactical radius of Japanese planes. Marcus, in the eastern part of the Nampo Shoto, was 825 miles from Saipan; its well-developed air base was an important stage along the outer route from Japan to the Marshalls and Gilberts.

Actually, the danger to the Marianas was more apparent than real. The heavy and sustained American attacks had left the enemy in no condition to launch a serious counteroffensive. His losses in planes and pilots had been disastrous, and in the face of the overwhelming superiority of U.S. land- and carrier-based air forces, he was unable to exploit the bases he still held. In the Gilberts and Marshalls battered Japanese garrisons did little more than keep alive. Truk, once exaggeratedly rated by Allied intelligence as the greatest naval base in the west Pacific, had been bombed into impotence. At Marcus, Wake, Yap, and Woleai, beleaguered forces labored to keep airstrips in repair for planes which seldom appeared. Only the Nampo Shoto could be counted a serious menace to B-29’s operating from the Marianas.

However slight the peril from other island bases, Admiral Nimitz, commander of U.S. forces in the Pacific Ocean Areas, could ill afford to neglect them. Neutralization by air and interdiction of the sea lanes had to be continued until war ended. Neutralization, deadly dull and without much in the way of visible results, occasionally fell to Navy or Marine air units, occasionally to B-29 groups in need of combat training, but the wheel horse in this task, as in the air defense of the Marianas, was Maj. Gen. Willis H. Hale’s diminutive Seventh Air Force, which on 1 August 1944 came under the control of Lt. Gen. Millard F. Harmon’s newly activated Army Air Forces, Pacific Ocean Areas.4 Harmon was also deputy commander of the Twentieth Air Force, charged with coordinating B-29 operations with Nimitz’ headquarters.

The Seventh’s few combat units were widely scattered and the

command setup was complicated. Administrative control was divided between Seventh Air Force, VII Fighter Command, and 7th Fighter Wing For operations, most combat units were under the commander of Task Force 59 (ComAirForward) and, later, his successor, the commander of Task Force 93 (StratAirPOA), who after 6 December was identical with Commanding General, AAFPOA.* But there would be exceptions: the 494th Bombardment Group (H), after its arrival in the Palaus in October, fought under FEAF in the Philippines campaign; at Okinawa the first AAFPOA units to arrive served with Task Group 99.2 (Tenth Army Tactical Air Force); and units of VII Fighter Command were directed by the commander of Task Force 93 in strikes against the Nampo Shoto, by the commander of Task Force 94 (ComForwardArea) in island defense, and by XXI Bomber Command in long-range missions over metropolitan Japan. Thus, although the Seventh took on additional responsibilities after its incorporation into AAFPOA, the bulk of its missions, as before, were for neutralization or interdiction; new targets were added and various units moved to new bases, but otherwise there was little to break the monotony of the campaign. From Kwajalein, some of the B-24’s of the 11th and 30th Bombardment Groups continued to stage through Eniwetok to strike at Truk, where the Japanese base, though effectively reduced during the Marianas campaign, still needed policing; between 1 August and 16 October the B-24’s went against it twice a week for a total of 499 sorties.5 Occasionally the B-24’s went out in training flights to bomb Wotje, Mille, Jaluit, and Wake. The B-25’s of the 41st Bombardment Group (M) continued to raid Nauru from Makin and Ponape from Engebi.6 Though none of these islands offered much in the way of a target and enemy reaction was usually feeble, constant surveillance, if tedious, was a necessary part of the strategy which had proved so successful to that time.

As AAFPOA units moved into the Marianas they found a livelier war. The 318th Fighter Group and one squadron (the 48th) of the 41st Bombardment Group had flown in after the assault troops had landed at Saipan and had rendered valuable close support in the seizure of that island, Tinian, and Guam.‡ Once the islands were secured, the 48th went back to Makin, and the 318th P-47’s, reinforced by

* See above, p. 529.

† See above, pp. 524-25.

‡ See Vol. IV, pp. pp. 690-93.

P-61’s of the 6th Night Fighter Squadron, took over the defense of the newly won bases. The P-47’s were also responsible for neutralizing lesser islands of the archipelago. For most of the islets an occasional visit was sufficient, but on Pagan an industrious garrison of perhaps 3,600 men repaired runways as fast as they were damaged; from August through March the P-47’s flew 1,578 sorties against that target.7

The B-24’s had begun moving into the Marianas in August, and by the end of October the 30th Group was at Saipan, the 11th at Guam. From their new bases the heavies still visited Truk, but increasingly they found their chief mission northward to the Nampo Shoto. On 11 August the 30th Group had sent 18 B-24’s against Chichi Jima in the Bonins and on 10 August had begun the neutralization campaign against Iwo Jima, previously hit by carrier strikes during the assault on the Marianas.8 Raids against those Japanese bases, and Haha Jima, became regular: against Iwo alone the Seventh Air Force dispatched ten missions in August, twenty-two in September, sixteen in October.9 As the B-29’s swung into action, Iwo Jima took on a new significance.

On 2 November, a week after the 73rd Bombardment Wing’s first practice mission against Truk, nine Japanese twin-engine planes swooped down for a low-level attack on Isley and Kobler fields. The intruders did little damage and three were destroyed. On the 7th there were two raids of five planes each and again the enemy lost three aircraft without doing much harm. There was then a lull until the B-29’s turned against Honshu.10 Early in the morning of 27 November two twin-engine bombers came in low, caught the Superforts bombing up for the second Tokyo mission, and destroyed one, damaged eleven.11 At noon on the same day, while the 73rd’s formations were over Tokyo, ten to fifteen single-engine fighters slipped through the radar screen for a low-level sweep over Isley and Kobler in which they destroyed three B-29’s and badly damaged two others.12 AAF fighters got four of the raiders; AA gunners shot down six others but also destroyed a P-47 under circumstances officially described as “inexcusable.”13 Next night some six or eight enemy planes bombed from high altitude without inflicting much damage. On 7 December, in a combined high-low attack Japanese intruders destroyed three B-29’s and damaged twenty-three.14 Using the same tactics, a force of about

* See above, p. 560.

twenty-five planes staged a party Christmas night in which they destroyed one B-29, damaged three beyond repair, and inflicted minor damage on eleven.15

This was the last large attack, though minor raids continued until 2 January, when the last Japanese bomb was dropped on Saipan, and enemy aircraft were sighted there as late as 2 February. In all, the Japanese had put more than eighty planes over Saipan and Tinian and had lost perhaps thirty-seven. This rate of loss spoke well of fighter and AA defense, and in normal operations would have been prohibitive to the enemy. But the intruders had destroyed 11 B-29’s and had done major damage to 8 and minor damage to 35; trading fighters and medium bombers for B-29’s in that ratio was not a bad exchange for the enemy, nor were his casualties appreciably higher than the toll of 45 dead and more than 200 wounded which he exacted.16

Although the enemy raids did not interfere seriously with the strategic campaign, they were an expensive nuisance which, if unchecked, could have become more costly. Serious or not, the losses were wasteful. Since the initial disasters at Wheeler, Hickam, and Clark fields, AAF commanders had been very sensitive about having their planes caught on the ground. Arnold was particularly touchy on this score, and because each B-29 represented a great investment, he had early expressed grave concern over defenses being provided for the VHB bases on Saipan. To bolster those defenses, the theater had been provided with a specially designed microwave early warning radar set (MEW),* which was supposed to be effective for planes coming in at low or high altitudes.17 Despite Arnold’s concern, there seems to have been little interest in the theater in installing the set on Saipan. Hansell and Hale both thought it would be more useful on Iwo Jima when that island was in US. hands and apparently Harmon agreed.18 The Navy, with final authority in the POA, felt that the air defense system was reasonably adequate and was reluctant to divert manpower from other high-priority projects. Accordingly, installation of the MEW drew a low priority.19

The early raids quickly dispelled any complacency about defenses, particularly since the enemy repeatedly slipped in under the radar screen – on the night of 27 November construction lights at Isley were still on when his planes struck!20 In a frantic effort to detect future

* This was a re-production set built by the radiation laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

intruders, Vice Adm. John H. Hoover, ComForwardArea, stationed 2 destroyers 100 miles northwest of Saipan to provide early radar warning, and an AN/TPS-3 radar was rushed to Saipan from Oahu by air.21 The destroyers in some instances gave ample warning, but on other occasions the enemy planes still managed to come in unannounced.22 As B-29’s were smashed on the hardstands and strips at Saipan, Arnold’s choler over the handling of the MEW increased, especially since he had sent the set to Saipan despite urgent requirements in Europe.23 Finally, on 3 December, Nimitz ordered Hoover to give highest priority to installation of the MEW, but it was not in operation until after the last Japanese bomb fell on Saipan.24 Although this inglorious history of the MEW serves to point up the difficulties inherent in a divided command, it is not the sole clue to the damage suffered at Saipan. The best of radar systems provided only passive defense, and in an attack resolutely pressed home enough enemy planes could escape the radar-alerted fighters and flak to menace aircraft on the ground. Both AAF and Navy commanders favored an aggressive policy – neutralization of the bases whence the enemy was mounting his raids.

It was commonly, and correctly, assumed that the Japanese planes were staging down from the homeland through Iwo Jima’s two operational fields. The risk of air attack had been realized even before the invasion of Saipan, and it was to prevent such tactics that carrier planes and the B-24’s had been sent against Iwo’s strips. But since the two groups of heavies had also been policing Truk, the Marshalls, and other islands in the Nampo Shot efforts were spread too thin.25 Navy authorities, concerned with the build-up of Japanese defenses in the Nampo Shoto, had directed much of the B-24 effort against shipping in the harbors of Chichi Jima and Haha Jima, evidently envisioning masthead attacks. In the heavily defended harbors such tactics were ill suited for the lumbering heavies, and at normal bombing altitudes the formations were too small to be effective. Hale protested this misuse of his B-24’s, but antishipping strikes continued until 25 November – with continued poor success.26

The first Japanese raids against Saipan, however, focused attention on Iwo. On 5 and 8 November Hansell sent his B-29’s against the island in training missions* and the rate of B-24 attacks was stepped up. Nimitz informed Hoover on 24 November that Iwo’s installations

* See above, p. 550.

would become immediately the primary target for all of Task Force 94’s aircraft,27 thus putting an end to the antishipping strikes. By the end of the month the heavies had run thirty missions against the island.28 In spite of them, however, the first Tokyo mission on 24 November provoked more serious raids from the enemy. Therefore, Nimitz sent Harmon to Saipan to try an all-out attack on Iwo’s installations by air and surface forces; if successful, such a coordinated strike might make it possible for the two groups of heavies to keep the Japanese airfields under control.29

Harmon arrived at Saipan on 5 December with plans for using Cruiser Division 5 and all available P-38’s, B-24’s, and B-29’s in a daylight attack. After a hurried conference with Hoover, Hansell, and others, Harmon scheduled the bombardment for noon on the 7th. Postponed because of weather, the attack was delivered on the 8th’ although the skies had not cleared. At 0945 twenty-eight P-38’s swept over the island, followed at 1100 by the B-29’s and at noon by the Liberators. Hoover’s cruisers began seventy minutes of shelling at 1347. The bomb load carried by the planes forcefully illustrated the difference in performance between the heavy and very heavy bomber at 725 miles tactical radius: the 62 B-29’s dropped 620 tons, 102 B-24’s only 194 tons.30 All told, enough metal was thrown to produce a good concentration on Iwo’s eight square miles, but because the bombers had been forced to loose by radar, results, so far as they could be judged from photography – handicapped, like the bombing, by adverse weather – were much less decisive than had been expected. Even so, the enemy’s raids on Saipan stopped until 25 December.

Arnold, worried about losses at Isley, had given his enthusiastic approval to the diversion of B-29’s from their strategic mission in this one instance,31 but thereafter the job of neutralization was turned back to the B-24’s. Harmon soon lost his earlier confidence that the bombers – or any other force – could keep the island completely neutralized.32 His pessimism was well founded. During December the 11th and 30th Bombardment Groups (H) flew 79 missions against Iwo; between 8 December and 15 February there was no day on which they were not over the island in at least 1 strike;33 and from November through January they flew 1,836 sorties. Joint attacks with surface ships were repeated on 24 and 27 December, 5 and 24 January. Night snooper missions, designed to impede repair activities, were sent out in the wake of daylight strikes. Yet at no time

Japanese Attack on Isley Field, 27 November 1944

Japanese Attack on Isley Field, 27 November 1944

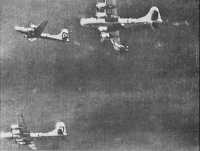

P-51’s on Iwo Jima

Japanese Weather

Japanese Defenses – Fighter Making a Pass under B-29

Direct Hit on B-29 by Flak

were all of Iwo’s strips rendered inoperational and no single strip was out of service for a whole day: the destructive Christmas raid on Saipan was run the day after a heavy air-sea bombardment of Iwo.34 The efforts of the Seventh Air Force were not wholly wasted, however, in spite of the enemy’s industry in filling craters day by day. Although it may have been their heavy losses over Saipan that induced the Japanese to discontinue their raids after 2 January, the steady bombardment by the Seventh’s B-24’s worked toward this end by discouraging, if not wholly denying, the use of the staging fields.

Even during the months when Iwo absorbed most of its attention, the Seventh went on with its routine neutralization of other enemy bases which could have threatened the Marianas. That mission was to continue until the summer of 1945, and it is useful here to interrupt the Iwo Jima story with a brief summary of operations elsewhere.

Marcus, through which planes could stage from Japan to Saipan – though with longer flights than via Iwo – was kept under constant surveillance, usually by armed reconnaissance missions of two or three B-24’s. Between September 1944 and July 1945 such missions totaled 565 sorties. Using Marcus as a target for shakedown missions, XXI Bomber Command dispatched eighty-five B-29’s against it during the last month of the war.35 Woleai was visited occasionally by AAFPOA planes, as was Yap, until responsibility for the latter island was turned over to a Marine air group at Ulithi in November.36 Truk, in spite of its severe mauling earlier, was considered a potential danger spot which needed more than sporadic armed reconnaissance, and missions were sent against its installations until the end of the war. Until 26 June 1945 it was AAFPOA’s B-24’s that did most of the work there, flying 1,094 sorties after 1 August 1944, of which 595 came after the t groups had moved from Kwajalein to the Marianas. The half-dozen or so fighters that the Japanese managed to keep patched up did not offer much resistance, but AAFPOA was generous with escorts, sending P-38’s in 75 sorties, P-47’s in 234 escort and strafing sorties.37

Until the assault on Iwo Jima the B-24’s continued the antishipping campaign in the Bonins. After 6 November there were no more bombing attacks, but with technical aid from NAVY officers the 42nd Squadron carried out a number of mining missions against harbors and anchorages in the islands. By 12 February the 42nd had planted 275 mines, about half of them around Chichi Jima.38 In his official report Harmon said that the squadron had not been successful in its

objective of clearing the area of all ships over 2,000 tons, and the Joint Army-Navy Assessment Committee credited the B-24’s with sinking only a single ship with its mines. Nevertheless, there was some belief in the Marianas that Harmon had deliberately minimized the effectiveness of the campaign “because mine-laying was not considered a proper function for B-24 bombers.”39

Capture and Development of Iwo Jima

Japanese raids against B-29 bases, though troublesome, were not important enough alone to have justified the cost of capturing Iwo Jima: the decision to seize the island was made a month before the raids began and they had ceased seven weeks before Iwo was assaulted. Meanwhile, the island had proved a hindrance to the VHB campaign in other ways. Since fighters based on the rock had attacked B-29’s en route to or from Japan, to avoid interception the bombers had been forced to fly a dog-leg course which complicated navigation and reduced bomb loads; even then, enemy radar at Iwo gave early warning to Honshu of northbound Superforts. But the idea of seizing the island derived less from its menace while in Japanese hands than from its potential value as an advanced base for the Twentieth Air Force.

The B-29 had been designed in 1940 to operate without escort, depending on altitude, speed, and firepower for protection. Later experience in Europe with the B-17 and B-24 had shown the need of fighter escort in attacks on heavily defended strategic targets, and while no fighter had been built with true VLR characteristics, the range of conventional escort planes had been so extended by 1944 that Arnold’s planners had become interested in the possibility of using them with the B-29’s, not from Saipan but from some island nearer to Japan. On 15 May 1944 Col. R.C. Lindsay of AC/AS, Plans, had recommended to OPD’s Staff Planning Group that islands in the Bonins and Ryukyus be seized for this purpose.40 The suggestion, though carrying strong AAF backing,41 aroused little enthusiasm in OPD, which thought that after the capture of Formosa – then an accepted operation – the Bonins and Ryukyus would become metropolitan Japan’s last bulwarks and would be defended so desperately that the cost of their capture would be incommensurate with their value as offensive bases.42 The air planners were not, however, convinced. On 14 July Arnold sent a memorandum to the JPS calling attention

to the Ki-84, a new and heavily armed fighter with which the Japanese might be able to inflict prohibitive losses on B-29’s over the home islands; to provide escort for the Superforts, he recommended seizure of Iwo Jima, within P-51 radius of Tokyo.43 JWPC, to whom the paper was referred, indorsed the proposal, subject to the proviso that it not interfere with the Formosa operation.44 This was on 21 July; a week later, assuming with his usual optimism that the JCS would go along, Arnold approved a project for assigning to XXI Bomber Command as many as 5 fighters groups, to include P-51’s and P-47N’s, the latter rated as having a tactical radius of 1,350 miles.45 Eventually, it was assumed, those fighters might conduct offensive sweeps over Japan as well as provide escort. Iwo Jima’s runways, moreover, if extended to VHB specifications, could serve as emergency landing fields or as staging bases for the B-29’s.

Harmon presented these arguments to Nimitz at Oahu, and during September the latter turned against the Formosa operation, favoring instead assaults by POA forces against the Nampo Shoto and the Ryukyus.* King accepted this view and at his recommendation the Joint Chiefs on 2 October scratched Formosa and set up the Nampo Shoto invasion for 20 January, Okinawa in the Ryukyus for 1 March. Their directive to Nimitz stipulated that the island selected in the former chain must be capable of supporting several airfields.46 That meant Iwo Jima.47 The island, whose name was unknown to the vast majority of American citizens, was to become associated in most minds with the U.S. Marines who took it foot by foot with rifle and grenade and flamethrower; but the sole purpose of the campaign was to provide an advanced base for the strategic bombardment of Japan.

Planning for the operation (coded DETACHMENT) began at once.48 Over-all control fell to Adm. Raymond A. Spruance, Commander of the Fifth Fleet. Under him, strategic control was vested in Vice Adm. Kelly Turner, Commander, Joint Expeditionary Force, and Lt. Gen. Holland M. Smith, USMC, Commander, Joint Expeditionary Troops. Tactical commanders were as follows: of the assault troops, V Amphibious Corps, Maj. Gen. Harry Schmidt, USMC; of the Amphibious Support Force, Rear Adm. W. H. P. Blandy; of the Gunfire and Covering Force, Rear Adm. Bertram J. Rodgers.49 The plan to base five groups of long-range fighters in the area led to the long debate over their control between Harmon and Arnold’s staff

* See above, pp. 390-92.

which has been described in an earlier chapter.* Eventually this was to be decided in favor of XXI Bomber Command, but Nimitz accepted the groups subject to their performing tactical and defense duties as well as escort. Accordingly, long-range fighters as well as Seventh Air Force B-24’s were to participate in the assault phase of DETACHMENT and control was vested in Harmon when he became commander of the Strategic Air Force, POA (Task Force 93) on 6 December.50

The time factor was crucial. Sandwiched between two major invasions, Lingayen Gulf and Okinawa, DETACHMENT had to be pushed through with dispatch. Its demands for support from carrier and surface forces had to be coordinated with the requirements of those other campaigns and of a carrier attack against Honshu in mid-February by Mitscher’s Task Force 58, a project much esteemed by the Navy. Available intelligence indicated that Iwo Jima had a strong garrison, difficult terrain, and was heavily fortified – and events were to prove that each of these items was underestimated. To reduce the hazards of the invasion fleet – Iwo was only 650 miles from Japan – the assault should be completed within a few days of launching. Marine planners, wishing to hold down losses in what at best promised to be a bloody struggle, insisted on a thorough bombardment by aircraft and naval gunfire; particularly they wanted extensive preliminary fire by battleships, whose heavy guns they had found more accurate and more effective than aerial bombs against dug-in defense points. They asked for ten days’ fire. Navy planners, viewing Iwo as only one of a number of scheduled operations, scaled down that request and the debate continued. In the long run, heavy fighting in the Philippine seas and the desire for additional antiaircraft guns for Task Force 58 reduced the battleship support available for DETACHMENT to an amount far below the estimates of the Marines. Events in the Philippines also disrupted the time schedule. When the Lingayen landing was postponed from 20 December to 9 January, the original D-day for DETACHMENT was no longer practicable. The date was set back, first to 3 February, then to the 19th. Further delay would have jeopardized Okinawa, which was postponed to 1 April.51

The operational plan, changed in detail a number of times, was essentially in final form by 31 December.52 The campaign was to begin on D minus 20, when the Seventh Air Force would step up its B-24

* See above, pp. 529-31.

attacks on Iwo Jima and Chichi Jima. On D minus 3, Admiral Rodgers’ force – eight battleships (six of them old), six cruisers, and sixteen destroyers – was to begin preliminary fire, now limited to three days, and Admiral Blandy’s escort carriers were to provide initial air support. Admiral Mitscher’s task force was ordered to support the launching at Iwo with its heavy guns and planes after it had made its strike against Honshu on D minus 3. The actual assault on the island was to be delivered by the 4th and 5th Marine Divisions, with the 3rd in reserve.

Predicated on a brief but bloody battle (three or four days instead of the four weeks actually required), plans called for an early development of three airfields, to be operational by D plus 7, D plus 10, and D plus 50 respectively.53 As soon as possible after the assault the responsibility for island defense was to pass from the Navy to the Air Defense Command, to be headed by Brig. Gen. Ernest Moore of VII Fighter Command. Moore was to be given a sizable force: signal air warning and antiaircraft artillery units; 222 P-51D’s of the 15th and 21st Fighter Groups; 24 P-51D’s of the 548th and 549th Night Fighter Squadrons; and a Marine detachment – 18 TBF’s of VMTB-242, later to be relieved by 12 PBJ’s of VMB-612. Subsequently another fighter group, the 306th, was to arrive with 111 P-47N’s.54

The XXI Bomber Command was asked to support DETACHMENT by coordinating its strategic missions with Task Force 58’s strikes and by assigning B-29’s to search and reconnaissance duties. Although the Twentieth Air Force had consistently resisted efforts to divert its B-29’s from their primary mission to the support of other Pacific operations,55 it would have been difficult to refuse aid for DETACHMENT, which was planned for its own special benefit. Fortunately, a regular strategic mission was agreed upon to keep Japanese planes busy at home, so that both at Washington and Guam there was ready acceptance of Nimitz’ proposal to integrate B-29 operations with those of the Fifth Fleet. LeMay, however, who was just taking over XXI Bomber Command, felt that the support originally requested was beyond his capacity and asked for a conference at Ulithi where he might work out with Spruance and Mitscher a more reasonable plan. After the meeting, held on 27 January, LeMay secured the approval of Nimitz and Harmon for the following supporting operations: 1) picketboat searches on D minus 8 and D minus 5; 2) weather-strike missions by three B-29’s operating individually against

Tokyo on three nights beginning D minus 4/3 and against Nagoya on three nights beginning D plus 3/4; 3) major strikes against a primary target in the Tokyo area on D plus 4; and 4) a diversionary raid against Nagoya on D minus 2.56

As this agreement was shaping up, DETACHMENT got under way. On 31 January Seventh Air Force B-q’s, which since August had been working over airfields and shipping in the Nampo Shoto, began their task of softening up Iwo Jima’s defenses. During the next 16 days the Liberators flew 283 daylight sorties (escorted on 3 occasions by some 15 P-38’s), dropping 602 tons of bombs and 1,111 drums of napalm; in the same period, B-24’s flew 233 night snooper missions, dropping 504 tons of bombs.57 On 12 February twenty-one B-29’s of the 313th Bombardment Wing expended eighty-four tons in a shakedown mission against pinpoint targets on Iwo:58 gun emplacements on Suribachi Yama, the formidable rock at the southern tip of the island, AA positions, and radar and radio installations. Bombing results were difficult to assess; in general they were considered disappointing and postinvasion inspection more than verified the pessimism of the early judgments. Bombing at moderately high altitudes and frequently forced by cloudy weather to make radar releases, the Liberator crews simply could not take out the assigned targets, most of which were cleverly concealed and deeply dug in. Napalm was dropped in an effort to burn off the camouflage, but the experiment failed, partly because of inaccurate drops, partly because of the nature of the cover. A Marine intelligence officer later judged that the chief effect of the long bombardment of Iwo was to cause the enemy to build more elaborate underground defenses.59

On 15 February, as Task Force 58’s fast carriers were moving in for the strike against Tokyo and surface forces were converging on Iwo Jima, LeMay sent out his B-29’s in their first support strike. Weather was bad over Tokyo and as a substitute target the planes bombed Mitsubishi’s engine works at Nagoya.* At Chichi Jima, fifteen B-24’s bombed the airfield but failed to do much damage. On the 16th Mitscher’s planes swept in to strike Nakajima’s Ota plant, and the next day they hit Musashi at Tokyo in a heavy attack. Weather was so bad in the area that a third strike, provisionally scheduled for

* See above, p. 571.

the 18th, was canceled and the task force moved down to cover the landings at Iwo Jima.60

Meanwhile, Blandy’s support force (Task Force 52) had moved into position off Iwo, and at 0800 on 16 February, an hour behind schedule, the big guns on the battleships and cruisers opened up. Mist had delayed the bombardment and low visibility and intermittent rain made it difficult for spotter planes to observe results. The escort carriers managed to put up 239 sorties during the day, but when 42 B-24’s came up from the Marianas to hit at targets on Suribachi, Blandy canceled the mission because of unfavorable weather.61 On 17 February (D minus 2), however, visibility was excellent, and the surface ships moved in to begin a complex schedule of round-the-island firing which had to be coordinated with the work of underwater demolition teams. The escort carriers put in a busy day, launching 336 sorties, which included strikes at defensive positions and antisubmarine and combat air patrols. The Liberators had better luck than on the 16th. Again 42 got up to Iwo, and going in at altitudes lower than usual – 4,900 to 5,700 feet – they dropped 832 x 260-pound frag clusters on defense installations just north of Suribachi’s crater. Results were rated “good.”62

Low clouds and occasional rain hampered air operations on the 18th. The escort carriers were able to send up 318 sorties, but when the B-24’s appeared the target was so completely covered with cloud that the strike was canceled. Nevertheless, it was a big day for Rodgers’ supporting ships. Weakened by a last-minute diversion to Task Force 58 of two 16-inch gun battleships and a cruiser, his force included only five old battleships and six cruisers. In spite of difficulties in observing results of their fire, these ships did an excellent job in destroying defense positions, concentrating especially on the landing beach areas. Their force was too light, though, and the period of preparatory fire too short so that a great majority of the defense installations remained intact.63

D-day, 19 February, dawned clear. Task Force 58, its Tokyo strikes completed, had come on for the assault and two of its battleships and thirteen cruisers joined in the neutralization fire as Marines shifted from transports into the landing craft. Between H minus 1 and H-hour (0800 to 0900), while the amphibious tractors maneuvered into position, the warships laid down a barrage, and aircraft

from the escorts and Mitscher’s fast carriers swept in. A strike by 44 B-24’s had been scheduled, but when over half of them aborted, only 15 arrived to drop 19 tons of 100-pound GP’s on the island’s eastern defenses.64

The first assault wave hit the beaches northeast of Suribachi at 0900, and under the Navy’s barrage moved inland about 200 yards on a 1,500-yard front. By evening 30,000 Marines were ashore: the 5th Division had pushed almost across the island at its narrowest point – just north of Suribachi – but the 4th, against very heavy opposition, had been stopped at the edge of Motoyama Airfield No. 1.65

The story of Iwo Jima thereafter is largely that of the Marines, a story of heroic fighting on the ground and under it. The Japanese commander, Lt. Gen. Tadamichi Kuribayashi, had organized his defenses with great skill, and with no room for maneuver the Marines had to pry the stubborn enemy troops out of their intricate cave strongholds. The island was not declared secure until 16 March, and isolated pockets held out even longer.66 Air played its part in the battle but it was not a leading role: B-29’s continued to attack Japanese cities; on 25 February Mitscher’s carriers launched another strike against the Tokyo area; carrier planes and the B-24’s kept hitting other islands in the Nampo Shoto; and a constant air patrol was maintained over Iwo Jima. Throughout the operation the Americans were thus able to maintain an overwhelming air superiority. There was no enemy air action on 16 February, by which time U.S. intentions had become quite clear, or on the 18th. The only serious air opposition came during the uncertain light of dusk on the 21st, when about a dozen Japanese planes made a low-level attack on a carrier unit, Apparently all the intruders were shot down, but they scored heavily, sinking the Bismarck Sea and damaging the Saratoga, the Lunga Point, and an LST.67

From the first day of ground fighting the Marines called for and received close air support against enemy strong points. Between 10 August and D minus 4, U.S. forces had dumped 9,616 tons of high explosives on the small island: B-24’s, 5,582 tons; B-29’s, 1,223; Navy surface ships, 2,405; Navy planes, 406. After the preliminary fire began on 16 February, Navy guns expended 9,907 tons of shells.68 Thus, the total weight of explosives rained on Iwo Jima amounted to about 2,300 tons per square mile. Yet many of the well-constructed and cleverly concealed positions were untouched69 and had to be captured

or sealed up by tank-infantry demolition teams with such direct air support as could be had. During the early days of the battle this service was rendered by carrier-based planes; ground commanders rated the pilots from Task Force 58 – some of whom were from Marine squadrons – as better than those from Blandy’s escort carriers and felt the loss of the former when the fast carriers departed on 22 February. On three occasions small formations of B-24’s were called up from the Marianas to bomb defensive positions,70 but the Seventh’s most important contribution to the ground fighting was through its fighters. The P-51’s of the 15th Group began to arrive at Iwo’s South Field on 6 March and flew their first mission on the 8th. Beginning on the 10th, the day before the escort carriers left, the P-51’s were on station from 0700 to 1830 in flights of eight planes. At the request of ground commanders they strafed and bombed enemy pillboxes, cave entrances, gun emplacements, slit trenches, troops, and stores, flying altogether 125 sorties. Although pilots were inexperienced in close support, they were daring and skilful and learned rapidly under Marine tutelage, pressing their strikes home to minimum altitudes. The aid thus given the ground troops was adjudged “material and timely assistance.”71

The 15th Fighter Group also furnished daylight combat air patrol: the group put up dawn and dusk flights of twelve P-51’s each from 7 to 11 March, after which the patrols were reduced to eight planes. At night two P-61’s of the 548th Night Fighter Squadron took over. This routine remained virtually unchanged until the end of the war although the chore was more widely distributed as new units arrived: the 549th Night Fighter Squadron on 20 March, the 21st Fighter Group on 23 March, and the 306th Fighter Group on 11 May.72

The dawn and dusk patrols were apt to be uneventful; no planes on combat air patrol were lost to enemy action. Iwo’s spotty weather during April and May often kept the patrols grounded and on 20 April was responsible for the loss of five P-61’s and three Marine PBJ’s which crashed in a heavy ground fog. Night work was more exciting, for the enemy occasionally attempted to bomb the island after dark – his last effort coming as late as 4 August. Japanese planes were able to get past the Black Widows on only three occasions: on 21 May when two bombers killed three men and wounded eleven before being shot down by flak; on 1 June when a single plane dropped a string of small bombs that killed five men and wounded seventeen;

and on 24 June when two Betty’s caused some small damage before being destroyed.73

The fighters also took over the job of neutralizing Chichi Jima and Haha Jima, previously targets for the B-24’s and carrier planes. The first strike was made on 11 March when the hard pressed 15th Group, its airfield still under occasional enemy artillery fire, sent out sixteen P-51’s. With General Moore flying as an observer, the formation divided eight tons of bombs between Susaki airfield and Futami Ko on Chichi Jima. Throughout March the planes went back in daily strikes that differed little from the maiden attempt. Priority targets were operational aircraft, shipping, Susaki airfield, and other military installations, but since enemy planes or shipping were seldom found, the main weight of attack was on the airfield. When Chichi was weathered in, the fighters hit Haha Jima; occasionally they visited the minor islands of the group.74 These visits continued until the end of the war. Day missions were run on an average of about one every other day, and from 29 March to 20 April P-61’s flew nightly harassing raids. Altogether, there were 1,638 sorties. Only two planes were lost to enemy action as opposed to eight lost from operational causes. Inadequate photo coverage made target selection difficult, and in truth there was little on the islands to hit. But the constant pecking away at the islands denied the enemy effective use of the airfield or harbors, and for fighter pilots the missions provided an invaluable transition between stateside training and the difficult VLR combat missions to Japan.75

These operations of the P-51’s and P-61’s had been made possible by the early development of the airfields for which the battle of Iwo Jima had been fought. Along the central plateau of Iwo the Japanese had laid out three airfields, sometimes called, from the neighboring village, Motoyama No. 1, No. 2, and No. 3 or simply South, Central, and North fields. The first had two strips, 5,025 and 3,965 feet long. Central Field had two runways, 5,225 and 4,425 feet, built in the form of an X. The third, with a single strip, never became operational.76 The basic plan (WORKMAN) for the development of Iwo into an air base, drawn up in October, contemplated the use where possible of existing Japanese facilities, and although the whole complex was to serve primarily as a VLR base, the most pressing job was the rehabilitation of some strips for local fighter use. The WORKMAN schedule, a Navy responsibility, was as follows: at No. 1, one 5,000-foot

runway was to be rehabilitated for fighter operations by D plus 7; at No. 2, the northeast-southwest runway was to be repaired for fighter use by D plus 10 and the east-west runway extended into a 6,000-foot fighter strip by D plus 50; later, by D plus 110, the northeast-southwest runway was to be extended to 8,500 feet for B-29’s and a second 8,500-foot runway was to be built parallel to the first; at No. 3, one 5,000-foot runway was to be ready for fighters by D plus 50. All runways were to be 200 feet wide. Construction was assigned to Cdre. R.C. Johnson’s 9th Naval Construction Brigade, made up of the 8th and 41st Naval Construction Regiments and one AAF unit, the 811th Engineer Aviation Battalion. The 8th Regiment was assigned to general construction, the other units to work on the airfields.77

Three Seabee units went in with the assault troops on D-day to serve as shore parties and to begin work on the airfields as they were overrun. Determined enemy opposition upset the construction schedule, but as the fields were captured, runways were rapidly made serviceable for minimum operations. One strip on South Field was being used by observation planes as early as 26 February (D plus 7), and by 2 March the other strip was graded to 4,000 feet. On the 9th, DETACHMENT paid its first dividend when a B-29 in distress came in for an emergency landing. Two days later the P-51’s came up from Saipan, and from then on, South Field was in constant use while construction was continued. Although work at Central Field was held up by the protracted land battle, on 16 March it too was operational, with one strip graded to 5,200 feet, the other to 4,800.78

On that day, Col. William E. Robinson, staff engineer for XXI Bomber Command, landed at Iwo Jima to survey the possibilities of VHB base development. From the point of view of B-29 crews, Iwo’s chief importance was that it would make fighter escort possible and serve as a haven for bombers in distress. But the planners had been interested also in its use as a staging base by which the tactical radius of the B-29 could be lengthened or its bomb load increased. It was for combat-loaded Superforts that the 8,500-foot runways had been designed, and the WORKMAN plan had provided facilities for 60 to 90 of the bombers. Robinson was convinced that North and Central Fields could be built to serve as many as 150 B-29’s, and after his return to Guam, he gave LeMay an amended base development plan. LeMay approved it on the day it was submitted, 26 March, as did

Maj. Gen. Willis H. Hale, who since Harmon’s death had been serving as deputy commander of the Twentieth. Maj. Gen. James E. Chaney, Saipan’s island commander, and Admiral Hoover readily concurred, so that by 4 April Robinson had carried the plan to Oahu where Admiral Nimitz gave his final approval. In Robinson’s plan, North and Central fields were to be combined into one huge airdrome covering over 4 square miles (half the surface of the island), with 2 VHB runways, 9,400 and 9,800 feet long, and a 5,200-foot fighter strip.79

The engineers found the task of building airfields on Iwo Jima complex and often exasperating. Iwo, which had risen from the sea within the memory of living men, was still a semiactive volcano, and in many places sulphur-laden steam issued from crevices, Some areas that were honeycombed with steam pockets had to be avoided when runways or subsurface gasoline lines were hid out. AlthougH the volcanic ash which covered the island’s surface worked more easily than the coral to which Pacific engineers were accustomed and could be readily compacted to sustain B-29 loads, when wet it eroded easily even if compacted, and asphalt could be laid on an ash base only when dry. Unfortunately, heavy rains in the spring months delayed construction by keeping the surfaces wet for as much as a week at a time. Even in good weather progress on the VHB runways lagged, until in April the Seabees began working two ten-hour shifts a day and reduced drastically the effort devoted to construction of their own housing and other secondary facilities. In June the program suffered a setback when an asphalt area of approximately 80,000 square feet at Central Field was ruined by water penetrating the subbase; on another occasion it was necessary to remove the crushed stone and subgrade from some 1,500 feet of asphalt runway.80

In spite of these difficulties, the first B-29 runway had been paved to 8,500 feet by 7 July and was in operation; by the 12th it had been paved to its full length of 9,800 feet. The second strip had been graded to 9,400 feet by V-J Day but was never surfaced. The old east-west runway became a 6,000-foot fueling strip. The fighter strip at South Field, in use by fighters since 6 March, was’ paved to 6,000 feet by July and had 7,940 feet of taxiways and 258 hardstands. At North Field, which in the revised plan was supposed to be incorporated with Central, the job involved new construction in rough terrain. By the end of the war the fighter strip had been paved to 5,500 feet and some 10,000 feet of taxiway had been graded. Fuel was supplied through

2 tank farms-one with a capacity of 80,000 barrels of aviation gasoline, the other storing 160,000 barrels of avgas, 50,000 barrels of motor gasoline, and 20,000 barrels of diesel oil – and through small installations at each field. There was at Iwo Jima practically no harbor development and all unloading was across the beaches.81

In this fashion Iwo Jima, once a threat to the VHB campaign against Japan, was transformed into a base whose chief purpose was to support that campaign. The work had not been finished by V-J Day, but during the six months between the landing of the first Superfortress on Iwo and the formal surrender in Tokyo Bay, the island was in constant use by VLR forces. Inevitably the question arose, “Was Iwo’s capture worth the cost?” Responsible leaders, using the impersonal calculus of high strategy, have agreed that it was. Lt. Gen. Holland M. Smith, whose point of view was that of the Marines, was emphatic on that score:

Yet my answer to the question, tremendous as was the price of victory, is definitely in the affirmative. In fighting a war to win, you cannot evaluate the attainment of an objective in terms of lives, or money, or material lost. I said “Yes” to this question before we laid plans to take Iwo Jima, and I say “Yes” today.82

The cost in human lives was heavy. U.S. losses, excluding Navy personnel, were estimated by USSBS at 4,590 killed, 301 missing, and 15,954 wounded, a total of 20,845. In return, the Americans killed an estimated 21,304 Japanese and captured 212.83 In a war of attrition this would have been an acceptable exchange, but the battle of Iwo Jima was for a small piece of valuable real estate, not primarily to inflict casualties upon the enemy.

Initial planning had stressed Iwo’s value as a base for VLR fighter escorts, and B-29 losses at the time of the battle for the island were serious enough to make these escorts seem necessary. Yet by late spring and summer Japanese air strength in the home islands deteriorated so rapidly that bomber formations again went out unescorted; the unexpectedly frequent use of the B-29’s in night missions also detracted from the importance of escorts. In all, the fighters were to fly some 1,700 escort sorties, a figure much lower, one would suppose, than had been anticipated. Nor did the B-29’s make much use of Iwo’s fields as a staging point where B-29’s could top off their fuel loads.84

The chief use made of the island was as an intermediate landing point, particularly for B-29’s in distress, and in this respect there can

be no doubt as to the great value of Iwo Jima. By the end of the war about 2,400 Superforts had made emergency landings on its runways;85 with 11-man crews, this involved some 25,000 airmen. Estimates of AAF lives saved because of Iwo’s strips have run as high as 20,000,86 but this seems a gross exaggeration. Certainly not all the 2,400 planes would have gone down at sea – indeed, possession of Iwo offered a constant temptation for B-29 crews in difficulty to use the midway point when there was a reasonable chance of making the home base. Furthermore, about half of the B-29 crewmen who went down at sea were rescued.* Perhaps the estimate cited by Admiral King that the lives saved “exceeded lives lost in the capture of the island itself” is the most accurate and just one.87

Possession of Iwo added flexibility to VHB operations. Missions could be dispatched during periods of uncertain weather in the Marianas with the understanding that returning aircraft would be diverted to Iwo if adverse landing conditions developed at their home bases. The B-29’s which had once avoided Iwo were now routed over the island, which served conveniently as an assembly and navigational checkpoint, making it possible to schedule missions with a take-off after midnight and a daylight return and landing. After this pattern was adopted, the rate of open-sea landings declined sharply and the rate of successful ditchings increased. The gains in combat effectiveness which resulted from improved morale cannot be measured but they were considerable. Changes in the tactical situation perhaps lessened the importance of Iwo Jima, but in sum XXI Bomber Command had great reason to be grateful for the sacrifice the Marines had made in seizing the island.

Air-Sea Rescue

Although Iwo Jima’s strips saved many an airman’s life, they did not eliminate the need for a comprehensive air-sea rescue (ASR) program for B-29’s operating out of the Marianas. Such a program had been begun at the time of the first training mission, and with subsequent improvements, some made possible by the capture of Iwo, it continued to function throughout the rest of the war. Like Iwo’s emergency landing fields, the elaborate precautions for search and rescue at sea paid off in two ways: in lives actually saved and in improved morale, which meant greater combat efficiency.

Three years of war in the Pacific provided a rich background of

* See below, pp. 606-7.

experience in rescuing airmen from the sea, yet although the problems involved in connection with VLR missions differed in degree rather than in nature from those encountered before, the differences were significant enough to exaggerate the difficulties inherent in this complex service. Something had been learned from XX Bomber Command’s missions over the Indian Ocean where the chief responsibility for rescue lay with SEAC, a combined command, but those missions had not been numerous nor were they, in general, so dangerous. For the missions out of Chengtu against Kyushu and Formosa, CINCPOA submarines had patrolled the adjacent waters but had never made a rescue.88

For XXI Bomber Command, the most obvious factor to consider was distance. It was roughly 1,400 miles between the Marianas and Honshu, not an excessive range for the B-29 but still a long haul over water with no islands along the route or on either side save for the enemy-held Nampo Shoto. Even when Iwo’s capture provided a midway haven the distances were formidable enough so that only those B-29’s which could reach the island in shape to make a power landing benefited from its strips. To increase bomb loads, operational officers kept fuel loads at a minimum and planes injured in combat or suffering from mechanical malfunctions or thrown off course by navigational errors faced the long return trip with insufficient gas reserves. Many were lost without leaving a trace; others were seen to crash, sometimes after crewmen had bailed out, sometimes without any sign of parachutes. Other B-29’s in trouble were deliberately put down at sea, usually in a power landing, a process known to airmen as “ditching.” It was a prime concern of XXI Bomber Command to rescue as many of these stranded crewmen as possible.

This was not easy. Even after Iwo’s capture the sea northward was infested with Japanese ships and planes. The ocean belied its name, Pacific. The route to Japan lay in the trade-wind belt where high winds were common and typhoons were occasional; heavy clouds and rain squalls reduced visibility, sometimes to zero; and pounding seas with whitecaps made search for a life raft a grim game of blindman’s buff and rescue a hazardous task. Even the job of ditching was more difficult than in the less turbulent waters of the Indian Ocean or Bay of Bengal where on occasion B-29’s had floated for hours after being set down.* And the distances which made ditchings frequent made search more difficult than in operations of normal range

* See above, p. 9.

by increasing the area to be conned and reducing the time available for orbiting the critical location. These difficulties were appreciated in a general way, if not in detail, from the outset, and efforts were made to modify existing procedures to meet the needs of VHB missions.89 But XXI Bomber Command was pioneering, and in air-sea rescue, as in other phases of operations, there was a period of adjustment in which performance was less than satisfactory.

In accordance with declared policy for the Twentieth Air Force, the Joint Chiefs made the CINCPOA responsible for air-sea rescue; he delegated the responsibility to ComForwardArea (Admiral Hoover) who set up an Air-Sea Rescue Task Group under Capt. H.R. Horney with task units at Saipan, Guam, Peleliu, Ulithi, and later Iwo Jima. Surface vessels were under the control of the Marianas-Iwo Jima Surface Patrol Group in the north and the Carolines group in the south. Lifeguard submarines were controlled by ComSubPac. Neither ships nor submarines were assigned permanently but were made available on request from Captain Horney as B-29 missions were dispatched.90 Though XXI Bomber Command had no responsibility, it had a most lively interest in rescue operations. In its headquarters at Guam an air-sea rescue section was established to maintain close liaison with Horney’s group, and after 15 December the VHB wings kept full-time liaison officers with Task Unit 94.4.2 in the Marianas.91

Negotiations between ComSubPac and XXI Bomber Command had preceded the beginning of training missions and the service began with the 73rd Bombardment Wing’s shakedown strikes; the first rescue came on 8 November when a B-29 returning from Iwo ditched and part of the crew was saved.92 The facilities made available for the first Tokyo mission included 5 lifeguard submarines on station north of Iwo Jima; 1 destroyer south of that island and another in the area 100 to 150 miles north of Saipan; 1 PBM on station just south of Iwo; and 3 PBM’s and 6 PB2Y’s standing by at Saipan. One B-29, short of fuel, ditched on the return trip and its whole crew was picked up by a destroyer.93 The record on succeeding missions was less reassuring. A third plane ditched on the Tokyo strike of 27 November and all on board were lost. Ditchings numbered sixteen in December, fifteen in January, fourteen in February. Of the forty-eight planes (B-29’s and F-13’s) lost in this fashion before 1 March, eight had gone down during miscellaneous missions (training, photo reconnaissance, weather, and search) and forty during strikes against

Empire targets. There were twenty such strikes during the period and on only three were there no ditchings; the average of two planes down per combat strike was costly. The worst day was 10 February when eight B-29’s on the Ota mission put down at sea. In November, December, and February a little more than a third of the crewmen who ditched were rescued, but in January the figure was only 12.6 per cent.94

Concerning those losses, the XXI Bomber Command was worried. So was Arnold. Shortly before relieving Hansell, Arnold wrote him somewhat querulously:–

I am also aware of the fact that some of these airplanes naturally must be ditched, but it seems on every raid there are three or four airplanes that go down, on the return trip, with no definite cause being given. It would seem to me that as the losses from this cause are constant and if added up, will present a large number, we should find the causes and determine what we can do to prevent them. In my opinion, the B-29 cannot be treated in the same way we treat a fighter, a medium bomber, or even a flying fortress. We must consider the B-29 more in terms of a naval vessel, and we do not lose naval vessels in threes and fours without a very thorough analysis of the causes and what preventive measures may be taken to avoid losses in the future.95

Since Hansell was on his way out, there was little more that he could do, but in his valedictory letter of 14 January, he challenged Arnold’s analogy: “The simile between the B-29 and the naval vessel is open to question. ... If the Navy committed its fleet or even all of its destroyers ... five or six times a month, their losses would be prohibitive.”96 Hansell had analyzed the losses and had begun remedial action which was to be pushed by LeMay when the latter took over the command. Hansell blamed part of the trouble on the complex command system in the air-sea rescue organization, with its divided responsibility for locating survivors and picking them up. This he hoped would be corrected by the practice already instituted of establishing in each wing a filter room for processing distress messages from its own aircraft; the signals were forwarded to a central control room operated by the Navy at Saipan, from which searches were directed.

There were two approaches to the problem of losses at sea: to reduce the number of planes going down and to increase the rate of rescues of crews that survived the ditching. For losses that occurred because of battle damage there could be no positive remedy, though Iwo’s capture was expected to help by providing fighter escorts and emergency landing strips. Other B-29’s went down because of mechanical

failures and the rate here, as in the excessive number of aborts, could be reduced by better maintenance and more rigid inspection. Hansell had initiated improvements in these respects which were continued under LeMay’s regime, and an intensive training program gave engineers and pilots a better understanding of flight control. More important, perhaps, was Hansell’s device of lightening the B-29 by stripping it of 1,900 pounds basic weight and removing 1 bomb-bay tank weighing 4,100 pounds when full. The total gross weight reduction of 6,000 pounds materially decreased power requirements, which in turn cut down on the frequency of engine malfunctions. On the first mission after this surgery, 19 January, there were no losses out of eighty bombers airborne and on the next, 23 January, there was but one ditching out of seventy-three sorties.97 Although this kind of luck could not hold in the face of the increasing tempo of operations, the rate of ditchings in terms of total sorties was never again to equal that set in January.

As for improving the rate of rescues, that was partly a matter of getting more and better equipment, partly of making better use of what was available. In the latter respects, the B-29 crews had much to learn. The original manuals on B-29 ditching procedures had been improved on the basis of experience in CBI, but Arnold complained on 23 January that narrative reports of ditchings indicated that crews were not assuming proper ditching positions and that emergency equipment was being improperly maintained and used.98 LeMay promptly called for more rigid inspections and intensified training for crews.99 The indoctrination program in the wings included lectures and practice in air-sea rescue procedures, and information as to available facilities was given at each premission briefing. But later inspections showed that equipment was still being misused. To cite a typical example, many planes were short of Mae West flashlights, invaluable in night ditchings, because crewmen borrowed them for use in their quarters and forgot to bring them along on combat missions.100 And the human factor in ditching and rescue was hard to predict or control. Those who have had to teach “ground school” courses to flyers will understand how difficult it is to impress them with the importance of any subject not immediately connected with an airplane in flight, and such lessons as were learned were often forgotten or disregarded in the traumatic experience of a rugged landing in an unfriendly ocean, especially at night. In the first ditching, that of 8 November,

only two crewmen escaped. When one of these, Sgt. Stanley J. Woch, was asked if there was anything wrong with the ditching procedure, he replied: “No, I cannot think of anything that was wrong; if the ditching had been like the ditchings in the book, and the plane behaved the way it should, everything would have been all right.”101

Even with the most skilful piloting there was a terrific shock when a 65-ton plane hit the water at a speed of more than 100 miles per hour, so that accidents frequently occurred which were not “in the book” and which no amount of training could forestall. An example chosen at random from a later period when air-sea rescue procedure was at its peak of efficiency will illustrate this point. In the early morning hours of 13 July, a B-29 from the veteran 58th Bombardment Wing was returning from a night incendiary strike at Utsunomiya. About two and one-half hours south of Iwo Jima the No. 1 engine went out, and then the fuel transfer system failed. This left too little gas to make it to Tinian on three engines, and when the crew sighted a convoy, the pilot, Lt. Irwin A. Stavin, decided to ditch. There was ample time and the crew made full preparations. Stavin contacted a Dumbo by radio and the Catalina was on hand when the B-29 hit the water in a perfectly controlled landing. Although the plane broke in two and sank in less than two minutes, all eleven of the crew got out; a sub chaser and an LSM from the convoy picked up the survivors within thirty minutes. Yet under these very favorable circumstances, the left gunner and the tail gunner were lost, having failed for some reason to reach the life rafts.102

Here the pilot had capitalized on the fortuitous meeting with the convoy, but in all probability the Dumbo would have been able to bring in some other rescue craft. It was locating survivors rather than picking them up that usually proved the more difficult task. The 48 B-29’s known to have ditched before 1 March would have carried, with normal crews, some 528 airmen; during that time air-sea rescue had spotted 164 survivors and had picked up every one of them.103 Most of the pick-ups had been made by surface vessels. During the early weeks of operations lifeguard submarines had made radio contacts with several downed crews but had never reached them. On 19 December the Spearfish rescued seven crewmen in a fine exhibition of teamwork on both sides, but it was not until 31 March that another underwater craft made a rescue.104 Some survivors broadcast their position in the clear and this made the submarines, vulnerable to enemy

attack, apprehensive of approaching; other B-29 crews, especially those going down off Honshu, simply refused to use either radio or flares for fear of being captured by the Japanese.105 Submariners blamed the flyers for taking chances on getting a damaged plane home rather than putting down near a submarine, “an uncertain factor to the Superfort boys.”106 This was not wholly because of lack of confidence; after all, pilots were supposed to bring their planes home if possible, or to Iwo. One pilot is quoted as saying facetiously, after being briefed on rescue procedures, “I don’t intend to ditch – Uncle Sam wouldn’t like it.”107 Although some airmen remained skeptical of the utility of the submarines, with experience and an increase in the number of lifeguard subs, the record was improved: a third rescue was effected on 27 April and in the late spring pick-ups became more frequent.”108 There was similarly an increase in the number of surface vessels on station and on call.

But the crux of the rescue problem lay in the effectiveness of the air search. Cooperation between Navy and AAF personnel in air-sea rescue units was good, but at the end of February, when a total of 129 Dumbo sorties had been dispatched, there was an impression in LeMay’s headquarters that the “Navy effort per B-29 ditched seems ridiculously low.”109 In part this was for want of enough planes, in part because of the reliance upon seaplanes: the Dumbos – PBY’s and PBM’s – had achieved an honorable record but were not ideally suited to the task at hand. One virtue, the ability to land on the water and make their own rescue after a successful search, was often negated by the rough seas. They lacked the range to patrol the whole area of B-29 operations-even after an air-sea rescue unit was set up at Iwo the areas beyond 30° North and 139° East were patrolled only by Superdumbos until late in June.110 The seaplanes were difficult to get up in an emergency and their lack of firepower and armor made them vulnerable to enemy interception. Yet in spite of pleas from XXI Bomber Command for land-based bombers for patrol, the first appreciable aid from the AAF came with the assignment of the 4th Emergency Rescue Squadron equipped with OA-10A’s, the AAF version of the Catalina. The first echelon arrived on 23 March and by early April a dozen of the planes had come, of which three were sent to Peleliu. Late in April, much to the command’s satisfaction, rescue equipment was reinforced by eight B-17’s specially equipped with droppable motorboats.111 The arrival at Iwo Jima of the escort fighters added to

the responsibilities of the rescue unit there. Yet though the P-51D or P-47N was helpless when its single engine conked out, either plane had a respectable radius of action and was quick to get away on an emergency call; the large number of fighters available made them useful in a spot search.

But only the B-29 had the endurance to hunt for long hours off the coast of Honshu where planes badly hurt in battle were apt to be lost. From the earliest raids Superfortresses in good condition were accustomed to stick by a wounded plane and to stand by as long as possible when it went down. This informal aid, called sometimes from its likeness to mass swimming practice the “buddy system,” was extended when VHB wing commanders were given permission to conduct independent searches with combat B-29’s. When LeMay assumed command, the shortage of Superforts had been eased somewhat with the arrival of units of the 313th Bombardment Wing, and from 22 January two of the giant bombers (or, rarely, F-13’s) were on station for each mission and many others were dispatched on special searches. With their great stamina – they averaged more than fourteen hours per search – the B-29’s proved so valuable that a special model, the Superdumbo, was developed for search and rescue work, This model carried additional radio personnel and equipment and much in the way of gear to be dropped to airmen in the water – pneumatic rafts, provisions, survival kits, and radios. The modified B-29’s, like other rescue planes, worked best when teamed with surface vessels or submarines, and it became standard practice to have two of the Superdumbos orbiting over each of the northernmost submarines by day and one by night, with four Superdumbos on ground alert at Iwo Jima. So heavy was the armament of these converted bombers that they were able not only to protect themselves but on occasion to drive off or destroy enemy planes or surface craft attempting to attack the lifeguard submarines.112

In spite of the continual expansion of air-sea rescue facilities, those most intimately concerned were never wholly satisfied with what they had. Yet toward the end of the war the rescue task group was able to cover the routes to Japan so thoroughly that there was no point on the briefed return track that could not be reached by rescue aircraft within thirty minutes and by destroyers or submarines within three hours. When the last B-29 mission was staged on 14 August, there were on station fourteen submarines, twenty-one Navy seaplanes

(PBY’s and PB4Y’s), nine Superdumbos, and five surface vessels. Besides these, surface craft were stationed off the ends of all runways, Navy patrol planes circled the waters nearby, and other rescue aircraft were on ground alert at Saipan and Iwo Jima. All told, some 2,400 men were on air-sea rescue duty, about 25 per cent of the total number engaged in the combat mission.113

With the growth of facilities there came also efforts to increase the efficiency of operations. Conferences between air and submarine officers were held at Guam in June to standardize communications systems, and eventually all planes, ships, and command posts concerned were put on a common radio frequency. Air search officers were taken on practice cruises in the underwater craft and submarine officers for flights in Superdumbos. B-29 crews were sent to ComSubPac’s rest camp on Guam for indoctrination and a submarine rescue lecture team toured the VHB fields.114 The effectiveness of these efforts is reflected in the following table of air-sea rescue statistics:115

| Month | Crew Members Known Down at Sea | Number Rescued | Per Cent Rescued | |||

| Ditched | Crashed | Parachuted | Total | |||

| Nov. 1944 | 36 | 0 | 0 | 36 | 14 | 39 |

| Dec. | 157 | 22 | 0 | 179 | 63 | 35 |

| Jan. 1945 | 122 | 33 | 0 | 155 | 20 | 13 |

| Feb. | 102 | 34 | 0 | 136 | 65 | 48 |

| Mar. | 107 | 0 | 0 | 107 | 79 | 74 |

| Apr. | 57 | 43 | 67 | 167 | 55 | 33 |

| May | 112 | 33 | 85 | 230 | 183 | 80 |

| June | 12 | 55 | 113 | 180 | 102 | 57 |

| July | 22 | 22 | 76 | 120 | 73 | 61 |

| Total | 727 | 242 | 341 | 1,310 | 654 | 50 |

From February on the monthly percentage of men rescued from those known to have gone down at sea shows a decided, if not a steady, improvement: only in April was there a serious break in the general trend. The figures become especially significant when projected against the spectacular increase in the rate of operations: thus the total known losses at sea in January were 125 men in 649 sorties, but in July were only 47 in 6,536 sorties.116

These statistics were of assistance to air-sea rescue officers as they sought to improve their service. The figures serve also to point up a fundamental difference between the American and the Japanese philosophy of war. The Japanese made but small provision for rescue service, while the Americans in the last B-29 mission, as was shown above, had one man at rescue work for each three in combat planes.

In addition to reflecting the concern for the individual characteristic of a democracy, this reflects also a hard-headed concern for a highly skilled combat team which had cost much in time and effort to produce: air-sea rescue paid off in protecting this investment as well as in humanitarian values. As the war moved on, Japanese flyers got progressively worse and US. flyers progressively better, and the attitude of each nation toward air-sea rescue was a contributing factor.

The statistics do not show, unhappily, the human side of the story – the long hours of frustrating search in the patrol planes, or the long hours of anxious waiting in the rubber rafts, or the patient and hazardous vigil in the submarines. No column of percentages can do justice to the skill and daring of the men who made the pick-ups off the very shores of Japan and from the Inland Sea itself, but the record is there to read in the logbooks of the submarines and in the circumstantial interrogation reports of survivors. There is no war literature that assays more richly in tales of derring-do.117

Nor do the statistics give any hint of the effect of air-sea rescue services on the individual airman. Stated in simple pragmatic terms, the figures might have shown the flyer that if he went down at sea in any fashion he had about a fifty-fifty chance of survival. If he ditched his chances were probably better, if he bailed out or crashed they were poorer. In any case his prospects were happier than if he parachuted over Japan. If he were a “percentage player” or a fatalist, the flyer might take comfort from the figures; some remained skeptical. On the eve of the Nagasaki atom bomb mission on 9 August, when rescue precautions were at their peak, Navy officers at the briefing stressed the ease and frequency of air-sea rescues. A member of the bombardment crew, Sgt. Abe Spitzer, comforted a dubious comrade: “It’s like a Gallup poll; nobody’s ever met anybody who was interviewed in a Gallup poll. Same thing; we never heard of anybody who’s been rescued.”118 But other crewmen had heard and there is no doubt that air-sea rescue took away something of the dread of the long return flight.