Chapter 20: Urban Area Attacks

6 March 1945 General LeMay summed up the record of XXI relations officer, Bomber Command in a disparaging remark to his public Lt. Col. St. Clair McKelway: “This outfit has been getting a lot of publicity without having really accomplished a hell of a lot in bombing results.”1 This was no reflection on McKelway’s office. From the Yawata mission of 15 June 1944 the Twentieth Air Force had maintained a policy of “factual reporting” of B-29 raids, and in the CBI and the Marianas, commanders had adhered loyally to that policy. In XXI Bomber Command headquarters there was a desire to plan releases in such fashion that it would not appear “that the B-29’s were seeking to hog all the credit,” and there was strong resentment that rewrite men at home were inflating the conservative reports sent out from the islands.2 But of the lack of significant results there could be no doubt. A day earlier the B-29’s had returned from their eighth unsuccessful mission against Nakajima’s Musashino plant and the failure to knock out that top-priority target was symptomatic of the entire bomber campaign.

Within a fortnight the picture was to change with a dramatic abruptness rarely experienced in strategic bombardment, where results are more often cumulative than catastrophic. The sudden improvement in bombing came with a change in tactics which was in its way as newsworthy as was the destruction wrought. For the change in tactics LeMay was responsible and its success was to mark him as one of the very greatest of operational air commanders of the war, but like most tactical revolutions this one must be viewed in the context of current ideas and events.

The Case for Fire Bombing

The B-29 had been designed largely at the instigation of those theorists in the AAF – sometimes called the “bomber radicals” – who were dedicated to the principles of daylight precision bombardment. When the plane was first committed to combat in June 1944, those principles had been under test in Europe for nearly two years, and the concurrent experiences of the RAF with night area bombing could be used as a control in the experiment. The results had not been wholly conclusive: there was no disposition among top AAF leaders to change from precision doctrines, but heavy losses to the Luftwaffe had shown the fallacy of the early belief that unescorted formations of bombers could regularly attack enemy targets. But since Japanese defenses were considered weaker than the German and since the B-29 with its great speed, firepower, and ceiling was superior to the B-17’s and B-24’s used in Europe, most of the early planning for the strategic bombardment of Japan had been based on the classic AAF doctrines. Hansell, who had been one of the most ardent exponents of those doctrines while working in Arnold’s headquarters and after coming out to the Marianas, attributed the failure of the early strikes against Japan to operational difficulties rather than to any flaw in the concept3 His reluctance to change his tactics, it has been suggested above,* may have been an important reason for his relief, for there had always been, both in Washington and in the theaters, men who advocated other tactics, and their influence had grown after Hansell’s departure. The argument for deviation from the doctrine of daylight precision bombardment hinged on three points: the cost of unescorted daylight missions, the vulnerability of Japanese cities to incendiary attacks, and the inconsiderable effects of pinpoint bombing with high explosives.

While XX Bomber Command was in training for MATTERHORN, several officers with wide bombardment experience – including Kenney, Fred Anderson, and LeMay – had expressed a preference for using the B-29 at night4 The 58th Wing had received relatively little training in night tactics but ran some of its missions especially when directed against Empire targets – by dark. The 73rd, on the contrary, had trained a few months later where, according to Hansell, “radar bombing at night was the principal tactical conception,”

* See above, p. 568.

and it was this indoctrination he blamed for the wing’s poor showing in day missions5 Although combat losses in operations from the Marianas had not been prohibitive, they had increased during January at a rate that made reconsideration of night tactics desirable. There was a popular belief in the United States that Japanese cities would be highly susceptible to incendiary attacks. When serious study of strategic air targets in Japan began in March 1943,6 there were many who agreed with this view. Tests conducted at Eglin Field and Dugway Proving Ground on model urban areas of typical Japanese construction seemed to add scientific confirmation to a judgment based on common sense. An air intelligence study completed on 15 October 1943 concluded that Japanese cities would prove much more vulnerable to fire bombing than had comparable German cities, because of more inflammable residential construction and greater congestion. Japanese military and industrial objectives were frequently surrounded by crowded residential sections and were hence exposed to sweeping conflagrations – indeed, much of the manufacturing process was carried on in homes and small “shadow” factories. Japanese industry, unlike German, was concentrated in a few cities, and it was estimated that the industrial areas of the twenty leading cities could be burned out with about 1,700 tons of M69 bombs – a 6-pound oil incendiary that was highly effective against light construction.7 This calculation referred to bombs actually on target, not to the total weight dropped, but even so AC/AS, OC&R, considered this weight much too light.8 Since subsequent efforts to revise the estimate produced no generally acceptable figure and since both operational and logistical agencies needed a realistic planning factor, it was especially important that test fire-bombing raids be run in the theater.

Such raids had been slow to materialize. The COA report of 11 November 1943, which guided the operational planning for MATTERHORN, stressed a long-range attritional campaign against steel and made no immediate provision for incendiary attacks.9 In spite of occasional prodding from Washington, XX Bomber Command did little in the way of fire bombing, so that when the COA rendered its second report on 10 October 1944, it had few combat data on which to rely. Following the report of a subcommittee which had recently completed a theoretical study on the economic effects of large-scale incendiary attacks on urban areas at Tokyo, Yokohama, Kawasaki, Nagoya, Kobe, and Osaka, the COA recommended such attacks on

those cities – but only after the raids could be “delivered in force and completed within a brief period.” In the meanwhile, they recommended that a test incendiary raid be run against some smaller city.10 The Joint Target Group indorsed this view, and the report of 10 October, with its emphasis on precision attacks with high-explosive bombs against the aircraft industry, became the basis of the target directives for XXI Bomber Command.11 Some officers on Arnold’s staff – including Col. Cecil E. Combs (Norstad’s deputy for operations), Col. J. T. Posey, Maj. Philip G. Bower, and several of those who had worked on the basic study of 15 October 1943 – thought the COA-JTG policy of delaying incendiary attacks over-conservative. It made sense to wait until there was force enough to cause a general conflagration in one city but, as Bower suggested, it was “an unwarranted extension of the sound basic policy” to hold off until all cities could be destroyed in successive attacks.12 Calculating the time when the requisite force would be available was difficult. Col. Guido R. Perera, AAF member of the COA, had on 8 June 1944 made a shrewd guess of March 1945.13 Bower, using the same planning factors as the JTG, estimated September; he thought the bomb weight suggested by the COA was too heavy and the date much too late for proper phasing. In addition to these theoretical considerations, there was by early 1945 a tactical issue: it was necessary to exploit the Philippine victory and the expected capture of Iwo Jima and to bring those home to the Japanese public; for such purposes, heavy fire raids against the chief cities would be more effective than precision strikes against factories in the suburbs.14

How much Arnold was moved by these arguments is uncertain; probably they had less influence than the failure of the precision attacks. In any event, his headquarters became progressively more interested in an all-out incendiary campaign. The results of the test raids against Nagoya (3 January) and Kobe (4 February) were studied in Washington but evoked “long-haired pros and cons” rather than firm conclusions.15 Nevertheless, Arnold’s target directive of 19 February indicated the significant trend: precision attacks on engine factories would still enjoy first priority, but incendiary attacks against the selected urban areas moved into second place ahead of assembly plants, and Nagoya, Osaka, Kawasaki, and Tokyo were designated primary targets under radar conditions. Moreover, a large-scale test raid against Nagoya carried an overriding priority.16 For tactical reasons

mentioned above,* the test was made at Tokyo on 25 February rather than at Nagoya and was most encouraging. In March, LeMay, with an increased force on hand, was committed to a heavier effort, what with the lagging Iwo campaign and the assault on Okinawa imminent: in a conference at Nimitz’ headquarters at Guam on 7 March XXI Bomber Command agreed to begin its pre-Okinawa campaign with maximum strikes against Honshu, L minus 22 to L minus 10 (9/10 March to 21/22 March).17 Conditions within the theater as well as Washington’s insistence urged a wider use of incendiary methods.

Early plans for precision bombing had assumed visual conditions over Japan. Experience had shown that assumption false. Since the attack on Kawasaki-Akashi on 19 January when bombing had been excellent, no mission had found visual weather over target; bombs hitting within a radius of 3,000 feet from the aiming point had varied from 17 per cent (rated “unsatisfactory”) to 0 per cent. Weather during the spring months was supposed to be worse and, with existing meteorological facilities, not accurately predictable. Most missions would have to rely on radar, and with the equipment and personnel available, this meant area bombing.18 For Japanese cities, incendiaries would be more effective in area attacks than high explosives.

The actual tactics to be used were the subject of much study by LeMay and his staff. The results of the Tokyo mission, though encouraging, were far from perfect. Like the other incendiary tests and LeMay’s successful fire raid on Hankow on 18 December, this mission had been run at high altitude.† Because of the high winds prevalent over Japan, accuracy under such conditions was difficult to achieve; moreover, the ballistic characteristics of the 500-pound cluster of M69’s rendered that bomb grossly inaccurate.19 A lower bombing altitude would increase accuracy, bomb load, and the life of B-29 engines. It might also increase losses to a prohibitive rate.

There was little in the way of pertinent experience to justify the change in tactics. The XX Bomber Command had done night mining at low altitudes (on one occasion going in under 1,000 feet), had bombed Kuala Lumpur from 10,000 feet by day, and had struck Yawata from as low as 8,000 feet by night.‡ Except for Yawata,

* See above, pp. 572-73.

† See above, pp. 143-44 and 573:

‡ See above, pp. 99, 109, 159,and 162.

however, those targets were poorly defended, and even Yawata had nothing like the array of antiaircraft guns massed around the great cities of Honshu. Some of LeMay’s flak experts thought it would be suicidal to go in over Tokyo or Osaka at 5,000 or 6,000 feet. But LeMay, a veteran of some of the heaviest air battles in ETO, considered Japanese flak much less dangerous than the German. Japanese gun-laying radar was not efficient, and searchlights, though plentiful and annoying, were no substitute for electronic control. In spite of the intense fire put up by heavy AA guns, statistics for the command’s missions were not too frightening: only two B-29’s were known to have been lost solely to that cause.20 The element of surprise should give the new tactics an advantage, at least initially.

As for enemy fighters, the chief cause of losses in daylight missions, there was less fear. Current intelligence credited the Japanese with only two units of night fighters in all of the home islands, and with them, as with the AA guns, radar equipment was not considered up to U.S. standards. Actually, LeMay proposed to send his B-29’s in without ammunition for their guns.21 In August 1944, when LeMay was at Arnold’s headquarters preparing to go out and relieve Saunders in XX Bomber Command, there had been both in Washington and Kharagpur a strong sentiment in favor of stripping some of the B-29’s of armament and using them, along with regularly armed planes, exclusively in night incendiary attacks.22 LeMay now had to balance the psychological effects of what amounted to disarming his bombers against the very real danger of self-inflicted damage among the B-29’s; the added bomb weight that could be carried in lieu of an average load of 8,000 rounds of machine-gun shells would be about 3,200 pounds, an appreciable increment.

In operational respects, there was much in favor of the night missions. Clouds over Japan tended to thin out at night and at the proposed altitudes winds were not too formidable. At night, loran sky waves came in more clearly than in day, making navigation easier. On the return flight, planes would meet an early dawn somewhere about Iwo Jima and it would be easier to land or to ditch damaged planes. Most important of all, the low altitude would allow a very heavy bomb load.23

These factors, and others, LeMay studied with his staff and his operational officers. In the end the command decision was his alone, though apparently his wing commanders (O’Donnell, Power, Davies)

were in accord with his plan. For the all-out effort against Japan in preparation for the Okinawa assault, LeMay was to launch a series of maximum-effort incendiary strikes, delivered from low altitudes. It was a calculated risk and like most such decisions it required great courage on the part of the commander. If losses should prove as heavy as some experts feared, the whole strategic campaign would be crippled and LeMay’s career ruined.24 Instead, the gamble paid off extravagantly.

The Great Fire Raids

LeMay’s decision came late. With the first mission set for the night of 9/10 March* (L minus 22 for Okinawa), the field orders were not cut until the 8th. Although operational details would vary significantly from normal practice, there was no tie to consult Washington as was so frequently done – Arnold was not even informed of the revolutionary plans until the day before the mission.25 The decision to attack at night ruled out the command’s standard technique of lead-crew bombing. Formation flying at night was not feasible, and with flak rather than enemy fighters the chief danger, a tight formation would be a handicap rather than a source of defensive strength. With planes bombing individually from low altitudes, bomb loads could be sharply increased, to an average of about six tons per plane. Lead squadron B-29’s carried 180 x 70-pound M47’s, napalm-filled bombs calculated to start “appliance fires,” that is, fires requiring attention of motorized fire-fighting equipment. Other planes, bombing on these pathfinders, were loaded with 24 x 500-pound clusters of M69’s. Intervalometers were set at 100 feet for the pathfinders, 50 feet for the other planes. The latter setting was supposed to give a minimum density of 25 tons (8,333 M69’s) per square mile.26

Since the first Empire strike, no mission had attracted such interest or anxiety. Planning had been shrouded in more than customary secrecy. Norstad, who had come out for a conference on the Okinawa operation, arrived at LeMay’s headquarters on 8 March and, when he had been briefed, alerted Lt. Col. Hartzell Spence, the Twentieths public relations officer in Washington, for “what may be an outstanding show.27 It was to be outstanding in size: 334 B-29’s would take off

* Although bombing on night missions usually occurred shortly after midnight, for sake of convenience they will be dated in this chapter by the day of departure.

with about 2,000 tons of bombs. More important, it was to be a most effective strike.

Planes from the 314th Wing’s 19th and 29th Groups took off from North Field on Guam at 1735 on the 9th. Forty minutes later the first planes of the 73rd and 313th Wings left for the somewhat shorter trip from Saipan and Tinian. It took two and three-quarters hours to get the whole force airborne.28 On the way out the B-29’s encountered turbulence and heavy cloud, but navigators easily identified landfall, coast IP, and the target area. Weather over target was better than usual, with cloud cover varying from 1/10 to 3/10 and initial visibility of ten miles. The first pathfinders readily located their aiming points and a few minutes after midnight marked them with fires that started briskly from the M47 bombs. The three wings came in low, at altitudes varying from 4,900 to 9,200 feet, and as initial fires spread rapidly before a stiffening wind, the B-29’s fanned out, as briefed, to touch off neb fires which merged to form great conflagrations.29

The area attacked was a rectangle measuring approximately four by three miles. It was densely populated, with an average of 103,000 inhabitants to the square mile (one ward, the Asakusa, averaged 135,000) and a “built-upness,” or ratio of roof space to total area, of 40 to 50 per cent, as compared to a normal American residential average of about 10 per cent. The zone bordered the most important industrial section of Tokyo and included a few individually designated strategic targets. Its main importance lay in its home industries and feeder plants; being closely spaced and predominantly of wood-bamboo-plaster construction, these buildings easily kindled and the flames spread with the rapidity of a brush fire in a drought, damaging the fire-resistive factories.30

The bombs-away message set the pattern for future reports: “Bombing the target visually. Large fires observed. Flak moderate. Fighter opposition nil.” Late formations reported general conflagrations that sent them ranging widely in search of targets, with visibility greatly reduced by smoke and with bomb runs made difficult by turbulence created by intense heat waves. Tail gunners on the trip home could see the glow for 150 miles.31

Opposition had been only moderately effective. The Japanese later admitted that they had been caught off base by the change in tactics, being prepared for neither the low-altitude approach nor the heavy

attack. The several B-29 formations reported flak of varying degrees of intensity and accuracy; automatic-weapons fire was generally too low and heavy AA too high, and the volume fell off sharply as fire or heat overran gun positions. Fighter defense, originally reported as “nil,” was weak throughout the three-hour raid. B-29 crewmen reported only seventy-six sightings and forty attacks by enemy planes, usually while the Superforts were caught in searchlight beams. Crewmen thought the interceptors worked without benefit of radar, being guided in solely by the searchlights, an assumption verified by postwar investigation. The fighters did not score, but flak damaged forty-two B-29’s and was responsible for the loss of fourteen, including five whose crews were picked up at sea by air-sea rescue units.32 The loss ratio in terms of sorties was 4.2 per cent as compared with a figure of 3.5 per cent for all B-29 missions and of 5.7 for January. In these moderate losses, as in damage inflicted on the enemy, LeMay’s tactics had been justified.33

So fierce was the fire that it had almost burned itself out by midmorning, checked only by wide breaks like the river. Photographs taken on 10 and 11 March indicated that an area of 15.8 square miles had been burned out. This included 18 per cent of the industrial area, 63 per cent of the commercial area, and the heart of the congested residential district. The XXI Bomber Command’s intelligence officers struck off their lists twenty-two numbered industrial targets.34

In October and November of 1945 a team of experts from USSBS made a thorough on-the-spot study of the effects of the raid. After surveying the physical features of Tokyo, examining the pertinent records, and interviewing officials and common citizens, the team was able to give a more detailed picture of what had happened.35

By Japanese standards, less exacting than American, Tokyo’s firefighting system was exceptionally good, with 8,100 trained firemen and 1,117 pieces of equipment, of which 716 were motorized. Static tanks for use with buckets or hand pumps were scattered throughout the residential districts, and the municipal water system, augmented by canals and reservoirs, was considered adequate for any emergency. In April 1944, in anticipation of air raids, a number of firebreaks were added to those created after 1923, all being articulated with the river and canals. The air-raid warning system was as good as any in Japan, but neither it nor bomb shelters were up to European standards.36

The new tactics caught the fire department by surprise just as they

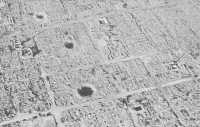

Nakajima-Musashi

Tokyo: burnt-out areas

Incendiary attack on Osaka

Incendiary attack on Osaka

Osaka: burnt-out area

did the military defense. The high concentration of bombs over so wide an area started so many fires that, according to the fire chief, the situation was out of control within thirty minutes. The flames caught and destroyed 95 fire engines, killed 125 firemen. Buildings of light construction were consumed utterly with their contents. There was little rubble left; only an occasional fire-resistant building, scarred by the heat, remained in the razed areas. Police records show that 267,171 buildings were destroyed – about one-fourth of the total in Tokyo – and that 1,008,005 persons were rendered homeless. The official toll of casualties listed 83,793 dead and 40,918 wounded. It was twenty-five days before all the dead had been removed from the ruins. Panic had been partly responsible for the heavy casualties, since persons trapped by spreading fires had tried to dash through the flames. Many found safety in the firebreaks, rivers, and canals, but in some of the smaller canals the water was actually boiling from the intense heat.37

Radio Tokyo labeled the raid as “slaughter bombing.” One broadcast reported that “the sea of flames which enclosed the residential and commercial sections of Tokyo was reminiscent of the holocaust of Rome, caused by the Emperor Nero.”38 It was good propaganda to picture LeMay as a modern Nero (though he smoked a cigar instead of fiddling while sweating out the mission), and there are passages in Tacitus’ famous account of the disaster of 64 A.D. that might have been applied to that of 10 March. But the physical destruction and loss of life at Tokyo exceeded that at Rome (where ten out of fourteen wards of a much smaller city were consumed) or that of any of the great conflagrations of the western world – London, 1666 (436 acres, 13,200 buildings) ; Moscow, 1812 (38,000 buildings) ;Chicago, 1871 (2,124 acres, 17,450 buildings); San Francisco, 1906 (4 square miles, 21,188 buildings).39 Only Japan itself, with the earthquake and fire of 1923 at Tokyo and Yokohama, had suffered so terrible a disaster. No other air attack of the war, either in Japan or Europe, was so destructive of life and property.

The effect on Japanese morale was profound.* An official of the Home Affairs Ministry later reported:

People were unable to escape. They were found later piled upon the bridges, roads, and in the canals, 80,000 dead and twice that many injured. We were instructed to report on actual conditions. Most of us were unable to do this because of horrifying conditions beyond imagination.40

* See below, pp. 754-55.

While Tokyo searched for its dead, the attack turned against other cities.

On the afternoon of 11 March, less than twenty-nine hours after the last plane had returned from Tokyo, a force of 313 B-29’s began taking off for Nagoya, Japan’s third largest city and hub of her aircraft industry. The XXI Bomber Command had visited Nagoya in six precision attacks and one test incendiary raid without significant results; this time the command would try to burn out the vital central and industrial core of the city in tactics similar to those used at Tokyo.41

The pathfinder planes again were loaded with M47 incendiaries. Had the supply been sufficient, these bombs would have been used exclusively, but there were not enough at hand; field orders called for the use of any incendiaries available in M69 clusters. Each plane carried 200 rounds of .50-caliber ammunition for the tail guns. The B-29’s had done well enough without ammunition over Tokyo, but eventually the enemy would discover that the planes were unarmed; moreover, some group commanders thought the tail gunners might knock out a few searchlights.42 The planes got off between 1710 and 1951. One ditched soon after take-off and nineteen others aborted. The 285 that reached Nagoya went in at altitudes from 5,100 to 8,500 feet and unloaded 1,790 tons, 125 more than had been dumped on Tokyo. The target area was a triangular wedge of the city with a built-up ratio approaching 40 per cent and a population of about 70,000 to the square mile. The aiming points were spaced to avoid blacking out the target for late arrivals and the target run was up wind. The 314th Wing was on target but the 313th and 73rd dropped short. Many fires were started – 394 separate fire areas were later identified – and some of these spread until stopped by firebreaks. Next morning a submarine 150 miles offshore reported its visibility cut to one mile by wood smoke.43

But there was no such general holocaust as had gutted Tokyo. Post-strike photos showed only 2.05 square miles destroyed, and this total was made up of many burnt spots scattered through the city. Eighteen numbered industrial targets (i.e., plants given a special designation in the target folders) were damaged or destroyed, but the aircraft plants were not wiped out. Most seriously hurt of this type of factory was Aichi’s Eitoku plant, but the decline in production thereafter was negligible – from 110 planes in February to 106 in March.44

That success was less spectacular than at Tokyo was due in part to circumstances over which XXI Bomber Command had no control. There was little wind to fan the fires started. Nagoya had an adequate water supply, well-spaced firebreaks, and an efficient fire department which adopted excellent tactics for the occasion.45 But there were also errors in planning that had resulted from misinterpretation of the huge success at Tokyo. For the Tokyo raid, intervalometers on all B-29’s except the pathfinders had been set to loose incendiary clusters at intervals of fifty feet. The stories of returning crews regarding the rapid spread of the fires created the false impression that bombs had been wasted by dropping them too close together. For Nagoya the setting was for intervals of 100 feet, which gave a density pattern too thin for the purpose desired. The method of attack, copied from Tokyo, also proved inefficient. The Superforts went over in two waves with bombardiers briefed to place their bombs visually in the vicinity of the aiming points so as to cover the entire area. Only a few planes made a controlled run over the target, and the attempt to scatter the bombs by snap judgment resulted in too wide a dispersal. There was no general conflagration.46

The mission cost little in the way of losses. The plane that ditched just after take-off was the only one destroyed. Twenty others were damaged, eighteen by flak and two by fighters. It was becoming clear, as LeMay had anticipated, that the Japanese had no successful tactics for night interception.47

For the third mission, LeMay had designated Osaka, not as yet hit by a major air strike. Osaka, situated on Osaka Bay, the eastern limit of the Inland Sea, was Japan’s second city in size and in industrial production. Its harbor facilities and excellent rail and highway connections made Osaka an important transportation center. It produced about one-tenth of Japan’s wartime total of ships, one-seventh of her electrical equipment, one-third of her machinery and machine tools. The Osaka army arsenal furnished 20 per cent of the army’s ordnance requirements. No airplanes were assembled at Osaka, but nearly a fourth of its half-million workers were engaged in the manufacture of parts and components for aircraft and engines. Osaka was also a great commercial city and an important administrative center. Because of conscription and the mushrooming of war industrial plants in the suburbs, the population of the city proper had shrunk from 3,254,380 in 1940 to an estimated 2,142,480 in February 1945. This

shift had reduced the density of population (to 81,000 per square mile for the central commercial section and adjacent residential-industrial districts) without greatly affecting the built-upness. The scene of many earlier disasters, Osaka had cut a number of firebreaks through congested areas to add to the protection given by its numerous canals and had built many modern fire-resistive buildings, but its crowded districts of highly inflammable houses offered an ideal incendiary target.48

The Osaka strike was scheduled before final results of the Nagoya mission had been evaluated. Reports from observers were sufficient, however, to raise doubts as to the correctness of the tactics followed, and operational planners tried to reproduce the pattern which had worked so well at Tokyo. The intervalometer setting was changed back to fifty feet and crews were warned to achieve a higher concentration in the target area. No specific method was prescribed although crews were briefed to check position carefully before releasing the bombs.49

Thanks to heroic efforts on the part of maintenance crews, the command was able to put up 301 B-29’s in a late afternoon take-off on 13 March. The planes carried the same 6-ton bomb load, but the low wing was given .50-caliber ammunition for lower forward and aft turrets as well as for the tail guns. When the force of 274 planes that got over Osaka found an 8/10 cloud cover, it had to resort to radar bombing. This proved an advantage rather than a handicap. Unable to sow their bombs by sighting visually on pathfinder fires, bombardiers were forced to drop after a controlled run, releasing on an offset aiming point. With this technique, the B-29’s achieved a thicker and more uniform pattern than had been possible with the impressionistic methods used at Nagoya.50

The results showed conclusively that the Tokyo raid had not been a fluke. The 1,732.6 tons dropped on Osaka in about three hours wiped out 8.1 square miles in the heart of the city. The chief commercial district was ruined, and fires were kindled in the industrial sections where 119 major factories were destroyed, including some engaged in heavy industry. As the flames spread rapidly, fire-fighting and air-raid protection (ARP) services were completely demoralized. Casualties mounted as persons were suffocated in makeshift shelters or were burned trying to run through the flames. The records of the Osaka fire department listed 3,988 dead, 678 missing, 8,463 injured.

The fury of the fire is indicated by the fact that 134,744 houses were completely destroyed as against only 1,363 merely damaged.51 In comparison, the cost to XXI Bomber Command was very light. Two B-29’s were lost – one at take-off – and thirteen were damaged. The enemy was alerted early enough to assemble his interceptor force but made only a feeble effort. The crewmen reported only forty individual attacks, and no Japanese fighter scored a hit.52

Maintaining the tempo of the fire blitz, LeMay sent his force to Kobe on the night of the 16th. Kobe, across the bay from Osaka, was Japan’s sixth largest city, her most important overseas port, and a focus of inland transportation. On either side the harbor and the commercial area lay important heavy industry installations. Kobe had been the target of a small test incendiary raid on 4 February and had caught a few stray HE bombs during the attack on nearby Akashi on 19 January,* but remained practically a virgin target.53

Operational officers, convinced that visual distribution methods were unsatisfactory, again changed some tactical details. The new field orders called for bombardiers to make a controlled radar run over the target before making visual corrections and to apply such corrections only to their sighting on the aiming point: they were not to spread bombs visually. Kobe, with its long irregular waterfront, provided an excellent radar target. The planners appreciated by now the value of greater concentration to insure the merging of individual fires. Flight schedules were accordingly changed to cut down the duration of the attack and the aiming points were plotted in a closer pattern.54

The bomb load was changed out of necessity: the supply of incendiary types previously wed was running low. Planning factors by which ammunition stocks had been accumulated had been outmoded by the build-up of forces and the change in tactics. Even more recent estimates were badly off. Only a month before, LeMay had calculated his needs on the basis of 4-ton loads for 735 sorties per wing per month, with bombs in a ratio of 60 per cent high explosives, 40 per cent incendiaries. For the three wings available in March this meant a total of 3,528 tons of incendiaries of all types. Now in three missions he had dispatched 948 planes loaded with about 3,900 tons, well over a month’s supply of incendiaries and drawn exclusively from the stocks of M47’s and M69’s. For Kobe the command had to use the

* See above, pp. 555-56.

M17A1, a 500-pound cluster of 4-pound magnesium thermite incendiaries. With 110 individual bombs per cluster, the M17 would achieve a wide dispersion and the thermite missiles would be effective in the dock and heavy industry areas, but they were not as destructive as oil bombs against flimsy dwellings. The chief merit of the M17 was its relative abundance.55

The attack on Kobe was the heaviest yet delivered and the most highly concentrated: 307 B-29’s dumped 2,355 tons in the short space of two hours and eight minutes. The Japanese were up in greater force than for the earlier night raids: B-29 crews reported sighting 314 enemy planes which made a total of 93 individual attacks, but the fighters were unable to interfere seriously. None of the three B-29’s lost was hit by fighters.56

In March 1944 Kobe had begun to clear out certain strips as firebreaks, but the program had been chiefly aimed at protecting individual targets rather than at preventing fires from sweeping over great districts. The fire early on 17 March quickly got out of hand, destroying the eastern half of the business district and burning out an important industrial area to the southeast. Among the many individual targets heavily damaged was the Kawasaki shipyards, where 2,000-ton submarines were built.57

There was some disappointment at Guam when poststrike photos showed that only 2.9 square miles – a fifth of the city’s area – had been burned over. Some of the heavy bomb load had been dissipated when navigators had failed to identify their aiming points or when crews, reluctant to penetrate the heavy thermals caused by the fires, had dropped their bombs short of their targets. Even so, Japanese statistics show that the destruction was appalling. About 500 industrial buildings were destroyed, 162 damaged. The loss of 65,951 houses left 242,468 persons homeless. Police reported 2,669 dead or missing and 11,289 injured.58

To round out his campaign, LeMay sent his planes back to Nagoya on the night of 19 March. Every third plane carried a couple of 500-pound GPs to disrupt organized fire fighting and loaded up to capacity with such incendiaries as were available in the f ast-dwindling dumps-M69’s for the 314th Wing, M47’s for the 313th, and M47’s and M76’s for the 73rd. Of 313 B-29’s dispatched, 290 got to Nagoya to drop 1,858 tons. Bombardiers were bothered by smoke and by searchlights, but by using radar techniques were able to blanket a considerable part of the city. The area burned was larger than in the

previous raid – three square miles as against two. Many important individual targets were damaged, including the Nagoya arsenal, the freight yards, and Aichi’s engine works, but the Mitsubishi plants escaped with minor damage.59

The second Nagoya raid brought the March fire blitz to an end. On the 9th, as he awaited the bombs-away signal from Tokyo, LeMay had remarked, “If this raid works the way I think it will, we can shorten this war.”60 The Tokyo raid had been all he could have hoped for, and the succeeding strikes provided additional evidence that the new tactics could indeed shorten the war. The statistics were impressive. With an average of 380 aircraft assigned, XXI Bomber Command had flown 1,595 sorties in 10 days. This was three-fourths as many as had been flown in all previous missions, and the 9,365 tons of bombs dropped was three times the weight expended before 9 March.61

Results had been more than commensurate with the effort. The B-29’s had left a swath of destruction across four key cities, laying waste to 32 square miles and destroying many important targets. The cost in crewmen had amounted only to 0.9 per cent of those participating, a loss ratio far under that of the daylight missions. The strain on both flight and ground personnel had been tremendous, but neither group showed signs of cracking. Maintenance crews who had worked round the clock to keep the B-29’s flying suffered from severe physical exhaustion but recovered rapidly. Combat crews, some of whom had flown all five missions, were fatigued but otherwise finished the ordeal in good physical condition. Morale was sky high. After months of small results and heavy losses, the B-29 had shown its capabilities, and airmen who had become discouraged in the dull routine of tallying combat missions in hopes of rotation took on a more aggressive spirit.62

On the tactical side, the implications of the five raids were clear enough. By bombing individually from low altitudes, B-29 crews had vastly improved the performance of their planes: bomb loads had been increased and engine strain had been diminished so that the command could get more sorties per plane. Radar, sufficiently accurate for area bombing, had taken some of the curse out of Japan’s weather. Neither flak nor fighters had been able to inflict serious losses at night. Most important of all, Japan’s urban areas had proved highly vulnerable to incendiary attack, as some airmen had long insisted. The new techniques could not be used efficiently against all targets, but under suitable

conditions they were so highly successful that the doctrines of strategic bombardment were to undergo a radical change.

Both Washington and Guam moved rapidly to exploit the new tactics. The Joint Target Group, after studying reports of the blitz, concluded that they were no strategic bottlenecks in the Japanese industrial and economic system except aircraft engine plants, but that the enemy’s industry as a whole was vulnerable through incendiary attacks on the principal urban areas.63 With this somewhat obvious rationale, the JTG designated thirty-three urban areas as targets of sufficient importance to warrant inclusion in a comprehensive plan of attack. Twenty-two of these were listed in a two-phase program, the first phase emphasizing destruction of ground ordnance and aircraft plants, the second, associated industrial production such as machine tools, electrical equipment, and ordnance and aircraft components. The remaining eleven areas were to be considered later, in light of experience in attacking the twenty-two. The order of the targets was a considered one. Each target was rated A, B, or C according to its relative industrial importance. A few (marked with an asterisk) had been hit before but their target value did not seem to be greatly impaired. The list was as follows:–64

| Target No. | Target Area | Rating |

| FIRST PHASE | ||

| 90.17-3600 | Tokyo UA/1 (i.e., Urban Area No. 1) | A |

| 90.17-3604 | Kawasaki UA/1 | A |

| *90.30-3609 | Nagoya UA/1 | A |

| 90.25-3617 | Osaka UA/1 | A |

| 90.17-3601 | Tokyo UA/2 | A |

| *90.25-3618 | Osaka UA/2 | A |

| 90.25-3618 | Osaka UA/3 | A |

| *90.20-3411 | Nagoya UA/3 | A |

| 90.20-3610 | Nagoya UA/2 | A |

| 90.34-3630 | Yawata UA/1 | A |

| SECOND PHASE | ||

| 90.17-3602 | Tokyo UA/3 | B |

| 90.17-3608 | Yokohama UA/2 | C |

| 90.17-3605 | Kawasaki UA/2 | A |

| 90.17-3607 | Yokohama UA/1 | B |

| 90.17-3606 | Kawasaki UA/3 | C |

| *90.25-3628 | Kobe UA/1 | A |

| *90.25-3629 | Kobe UA/2 | B |

| 90.25-3624 | Amagasaki UA/1 | A |

| 90.25-3620 | Osaka UA/4 | B |

| 90.35-3621 | Osaka UA/5 | B |

| 90.25-3625 | Amagasaki UA/2 | B |

| 90.20-3612 | Nagoya UA/4 | B |

| REMAINING AREAS | ||

| *90.17-3603 | Tokyo UA/4 | C |

| 90.20-3613 | Nagoya UA/5 | B |

| 90.2-3614 | Nagoya UA/6 | B |

| 90.20-3615 | Nagoya UA/7 | C |

| 90.20-3616 | Nagoya UA/8 | C |

| 90.25-3622 | Osaka UA/6 | C |

| 90.25-3623 | Osaka UA/7 | C |

| 90.25-3626 | Amagasaki UA/3 | C |

| 90.25-3627 | Amagasaki UA/4 | C |

| *90.34-3631 | Yawata UA/2 | B |

| *90.34-3632 | Yawata UA/3 | C |

[Table data merged onto previous page]

In addition, the JTG named certain priority industrial targets: Osaka Army Arsenal, Kure Naval Arsenal, Hiro Arsenal, Kokura Arsenal, Sasebo Naval Arsenal, and the Koriyama chemical works. In setting up two parallel target systems, the one for area, the other for precision attacks, the Joint Target Group established the pattern which was to guide strategic bombing during the rest of the war.65

On the basis of the JTG recommendation, the Twentieth Air Force on 3 April issued a new target directive. Nakajima-Musashino and Mitsubishi’s engine works at Nagoya still enjoyed top billing. Second only to these, and without internal priority, the directive listed six of the first-phase urban areas: Tokyo UA/1, Kawasaki UA/1, Nagoya UA/1, Osaka UA/1, Osaka UA/2, Osaka UA/3.66

The Joint Target Group based its recommendations on the assumption that the principal function of air attack was to pave the way for an invasion of the home islands. This was the official view and strategic planning favored landings on Kyushu in the autumn. But after studying the results of the March fire raids, LeMay came to the conclusion that with proper logistic support air power alone could force the Japanese to surrender – a view shared privately by some members of Arnold’s staff in Washington.67 LeMay established a new set of planning factors, derived from his March operations, to serve for the six months from April through September. During March, XXI Bomber Command had achieved an operational rate of seven sorties per plane per month. Deployment schedules listed the 58th Wing as available in May and the 315th in July, with an increase in aircraft on hand from 148 to 192 per wing. By maintaining the March rate, LeMay figured his sortie effort as follows: April, 2,925; May, 3,851; June, 4,597; July, 5,460; August, 6,025; September, 6,700.

Combat crews presented a more serious problem than aircraft. Sixty flying hours per month were considered the maximum a crew could endure over a long period. With this limitation, an expected loss

rate of 2 per cent, and a tour of duty of approximately thirty-five missions, LeMay would need many more crews than he had been promised. This disparity between his needs and his expected receipts was presented graphically in the following table, which was sent to Washington by teleconference on 13 April:68

| Month | Crew Receipts Required | Crew Receipts Forecast | Monthly Shortage | Cumulative Shortage Crew |

| April | 152 | 152 | 0 | 0 |

| May | 282 | 106 | 176 | 176 |

| June | 217 | 130 | 87 | 263 |

| July | 407 | 148 | 259 | 522 |

| August | 529 | 245 | 284 | 806 |

| September | 324 | 222 | 102 | 908 |

The forecast crew shortage would curtail seriously the combat effort as figured on the basis of aircraft available, reducing the estimated number of sorties by 469 in May, 777 in June, 1,323 in July, 1,900 in August, and 2,320 in September. By 30 September, the cumulative shortage would reach 6,789, or about 23 per cent of the total number of sorties scheduled. There was one partial solution to the problem. During March B-29 crews had flown eighty rather than sixty combat hours each. If they could maintain this pace for six months, they could cut down the cumulative shortage to 2,920. LeMay’s flight surgeon and his wing commanders were convinced that the rate of eighty hours per month for six consecutive months might burn out his crews – even the sixty-hour rate was greater than that maintained by the Eighth Air Force. But LeMay in another difficult command decision elected to take the risk, to drive his crews at the rate of eighty hours a month. It was a short-term policy, deliberately adopted in the hope that it would bring about a quick and decisive pay-off.69

Again, as in the decision to launch the low-level night attacks, the calculated risk had some comforting arguments in its favor. Combat crews had come through the March blitz in remarkably good shape; though nervous fatigue would be a limiting factor in extended and heavy operations, performance had indicated that the B-29 crews could be “flown to death.” LeMay summed up his attitude in a message to Norstad on 25 April:–

“I am influenced by the conviction that the present stage of development of the air war against Japan presents the AAF for the first time with the opportunity of proving the power of the strategic air arm. I consider that for the first time strategic air bombardment faces a situation in which its strength is proportionate to the magnitude of its task. I feel that the destruction of Japan’s ability to

wage war lies within the capability of this command, provided its maximum capacity is exerted unstintingly during the next six months, which is considered to be the critical period. Though naturally reluctant to drive my force at an exorbitant rate, I believe that the opportunity now at hand warrants extraordinary measures on the part of all sharing it.”70

This view was not for public consumption. The AAF had stressed the importance of playing up the teamwork of the several services in public utterances, and the experience in Europe had shown how difficult it would be to defeat an enemy by air power alone. LeMay kept trying to increase his rate of crew replacements, even offering to accept B-17 and B-24 crews with a minimum of transition training, but in the meanwhile he would use what resources he had in an effort to break the enemy’s ability and will to resist.Before he could launch the heavy attack on Japanese industry, however, LeMay had to fulfill commitments in support of the Okinawa campaign which had begun with the landings on 1 April.

Support of ICEBERG

The accelerating pace of the Allied drive toward the heart of the Japanese Empire during 1944 and 1945 inevitably brought some changes in the schedule of planned operations. Such was the case when the Joint Chiefs decided on 2 October to bypass Formosa (set up for 15 February 1945) in favor of a landing in the Ryukyus on 1 March.* Nimitz had suggested the change, and in compliance with a JCS directive of 3 October he put his staff to work on a plan for the capture and development of Okinawa, largest island in the Ryukyu chain. The assault operation, which turned out to be one of the bloodiest jobs of the Pacific war, was largely the work of POA forces whose story has been told in detail by others.71 Because the chief purpose of the campaign (coded ICEBERG) was to secure air-base sites near Japan, the AAF was keenly interested in the operation. Plans called for the development of VHB bases which would have helped in the strategic bombardment of Japan, but those fields were to be built too late to serve the B-29’s, and meanwhile the support rendered by XXI Bomber Command was to retard seriously its primary strategic mission.

The CINCPOA planners had to assume that earlier operations would have progressed enough to release forces needed at Okinawa:

* See above, pp. 392-93.

Navy support units, air and surface, from Iwo Jima and ground and Navy combat units, with assault shipping, from the Philippines. They also had to assume that preliminary operations would secure for the expeditionary forces control of the air in the target area. It early appeared that success or failure of the operation would turn on air superiority: the enemy’s fleet was too battered to offer a serious challenge, and if a sufficient ground force could be put ashore and supported, it could overcome the island defenders even though they fought with their customary skill and courage. In the air the enemy might prove formidable. The Japanese thoroughly appreciated the importance of Okinawa and could be expected to throw against the assault forces and their support ships the full weight of the homeland air forces, augmented by units withdrawn from the Philippines. Okinawa was little more than 300 miles from the southern tip of Kyushu, and airfields on the latter island were within operating radius of the invasion zone for all categories of aircraft; conversely, the distance from the nearest U.S. bases, on Luzon, was too great to allow assault support by land-based fighters.72 As plans for ICEBERG developed, the Japanese unleashed in the battle of Leyte Gulf a new and terrible air weapon in the kamikaze , or suicide, plane.* The threat of such a weapon in the hands of fanatics was grave enough materially to affect the plans for the assault.

Nor were the planners mistaken in their concern: time was to show how heavily the Japanese had counted on the kamikaze . Its very considerable success in the Philippines, where 174 hits or damaging near misses were scored, was exaggerated by Japanese military leaders, partly in ignorance, partly for propaganda purposes; and a large number of “special attack units” were organized by both army and navy air forces. With personnel drawn from combat units and training organizations and with all manner of aircraft, including obsolescent and training planes, the kamikaze force would constitute the main strength of the Fifth Air Fleet defending Okinawa. The high command hoped that mass suicide, or kikusui, missions would destroy U.S. naval units and supporting craft and so isolate the assault troops that the Japanese Thirty-second Army, charged with the ground defense of Okinawa, would be able to drive the invaders into the sea.73

Plans for ICEBERG were worked out in broad outline in a conference

* See above, pp. 356, 363, 368-69, 479-91.

(FIVESOME) at Hollandia in early November 1944.* The Twentieth Air Force was represented by Col. William Ball who had just come out from Washington to join Harmon’s staff as deputy commander for operations. Arnold and his theater commanders were concerned over the amount of B-29 effort that would have to be diverted from the primary mission of both the XX and XXI Bomber Commands. The support agreed on tentatively at Hollandia consisted of reconnaissance of Okinawa and strikes against airfields in Kyushu and Formosa from which the enemy could attack the invasion forces. The Joint Chiefs and the theater commanders involved accepted the plan subject to certain modifications, and Arnold made it clear that final approval would be contingent on the choice of suitable objectives for the B-29’s: normally airfields were not considered proper VHB targets.74

Subsequent events in the Pacific and in CBI brought changes in the plans for B-29 cooperation. The decision of 15 January to withdraw XX Bomber Command from its China basest canceled its part in the program save in respect to photo reconnaissance of the Ryukyus.75 Delays in MacArthur’s Luzon campaign forced Nimitz to set back his L-day from 1 March to 1 April, and in the meanwhile XXI Bomber Command was forced to carry out, in the face of bad weather, a number of photo-reconnaissance missions over Okinawa.76 On 7 March representatives of Nimitz, AAFPOA, and LeMay met to draw up a final plan for B-29 support for ICEBERG. They proposed the following schedule:

1. L minus 22 to L minus 10: maximum operations against Honshu.

2. L minus 20 and L minus 10:photo reconnaissance of Nansei Shoto, with particular attention to Okinawa Gunto, if requested by CinCPOA.

3. When requested: reconnaissance of enemy picket boats in specific areas desired by CinCPOA.

4. L minus 10 to L minus 5: a) L minus 10 or L minus 9 (depending on weather), attack against Kyushu air installations, as selected by CinCPOA, if visual bombing possible. Under radar bombing conditions, attack will be made against Nagasaki or Omura. b) L minus 6 or L minus 5, repeat above plan of attack.

5. L minus 10 to L minus 5: mining of Shimonoseki Straits with 1,500 mines which it is estimated will effect complete closure for four weeks.

6. After L minus 5: full-scale operations against Honshu will be resumed.77

* See above, pp. 146-47, 404-5.

* See above, pp. 151-52.

LeMay, busy with his fire raids, did not like this schedule. He forwarded it to AAFPOA on 12 March but next day suggested to Arnold a revised program: paragraphs 2 and 3 were eliminated and the operations planned in paragraph 4 were to be limited to a single mission, delivered on L minus 5 or 4.78 This plan Arnold accepted in a message of 15 March but within a few hours dispatched a second message withholding final approval until he had been informed of the specific targets on Kyushu.79 The targets, in order of priority, were airfields and installations at Kanoya, Miyasaki, Tachiarai, Nittagahara, Kagoshima, Omura, Oita, and Saeki. These Arnold accepted, but with the proviso that the attacks were to be made against permanent installations rather than the strips, unless the latter were crowded with planes.80 The target directive issued by the Twentieth Air Force on 3 April* reaffirmed the importance of the B-29’s primary mission but without compromising the commitments in support of ICEBERG. In spite of a continuing reluctance to use the B-29 as a tactical bomber, Arnold’s office was willing to go beyond minimum requirements as stated in the original JCS directive governing Twentieth Air Force operations.† According to that arrangement, Nimitz as theater commander could direct the employment of XXI Bomber Command in a tactical or strategic emergency. Norstad, in a long teleconference of 31 March, informed LeMay that the Twentieth’s primary interest was to insure the success of ICEBERG at a minimum cost of time and of casualties. LeMay was to tell Nimitz that CINCPOA could use XXI Bomber Command whenever the B-29’s could have a decisive effect whether an emergency existed or not.81 Effectively, this was to give Nimitz control of most of the B-29 effort during the next five weeks.

Meanwhile, the Okinawa operation was getting off to a late start. The assault was to be mounted from Leyte, Saipan, Oahu, and the west coast of the United States, and as the scattered Army and Marine units of Lt. Gen. Simon B. Buckner’s Tenth Army were getting their final training, Navy and AAF planes were at work softening up the Ryukyus and Kyushu. During February and March aircraft from the Marianas or SWPA were over the Ryukyus almost every day; search and patrol bombers covered the adjacent seas. Planes from Mitscher’s Task Force 58 had hit Okinawa in October and January, in preparation for Leyte and Luzon, and again on 1 March. On 18 and 19 March

* See above, p. 625

† See above, p. 38.

the task force worked over airfields and harbors on Kyushu, Shikoku, and western Honshu. On the 26th and 27th, the 77th Infantry Division landed on the Kerama Islands, fifteen miles west of Okinawa.82 On the latter day, XXI Bomber Command flew its first scheduled mission against Kyushu. Targets were the Tachiarai Army Airfield, the Oita Naval Airfield, and the Omura aircraft plant. Tachiarai was important as a training center, as an air base, and as seat of an army air arsenal; Oita had both a seaplane and fighter base. The Omura plant was new and large and apparently important as a factory and repair base. LeMay’s crews had enjoyed some rest after the fire blitz, broken only by a 250-plane raid against the Mitsubishi plant at Nagoya on 24 March. Now, on the 27th, 165 B-29’s from the 73rd and 314th Wings got off. They met little opposition over Kyushu, and 151 planes bombed the primary targets, destroying or damaging 606,500 square feet at Tachiarai, 112,175 at Oita, and 250,000 at Omura.83

That night the 313th Wing sowed aerial mines in the Shimonoseki Strait. The mission was intended to bottle up the Inland Sea during the Okinawa assault, but it inaugurated a mining campaign which was to have strategic as well as tactical objectives.* The 314th sent 12 planes against the Mitsubishi engine works at Nagoya on the night of the 30th.84 Next day – L minus I for Okinawa – XXI Bomber Command flew its second diversionary mission against Kyushu, returning to Tachiarai and Omura. Of 152 planes airborne, 137 bombed with excellent results. The Tachiarai machine works was completely destroyed and the airfield at Omura, the other primary target, was liberally plastered with high explosives. Enemy fighters scored hits on fifteen B-29’s but without knocking any down.85

Meanwhile, final preparations for the landing at Okinawa had been made: carrier-based planes had worked the island over, naval gunfire had softened up defense positions, minesweepers and underwater demolition teams had cleared a path to the shore. At 0830 on Easter morning, 1 April, Marines and Army infantrymen stormed the Hagushi beaches. The landings, contrary to estimates, proved easy. More than 16,000 troops were ashore in an hour, more than 60,000 by nightfall. The assault troops rapidly expanded their positions, and by 4 April the Tenth Army held a chunk of Okinawa fifteen miles long and three to ten miles wide, including two airfields of great potential importance, Yontan and Kadena. Kamikaze planes had hit the West Virginia

* See below, pp. 662-74.

and two transports, damaged two LST’s, but air resistance, like the defense of the beaches, had fallen far short of expectations.86 The XXI Bomber Command, having done its stint of mining and its two scheduled strikes against Kyushu, turned back to its strategic campaign with a mission against Nakajima-Musashino on 1 April,87

All hopes for an easy victory at Okinawa were soon dissipated, however. On 6 April the Japanese opened up with one of the most furious air counterattacks of the Pacific war. About 355 kamikazes and almost as many conventional fighter and reconnaissance planes flew down from Kyushu to hit at shipping and ground forces ashore. An elaborate defense against just such a mission had been set up, with picket boats, carriers, an air patrol, and flak of all calibers. Claims of Japanese planes destroyed ran to 300, but suicide crashes sank two destroyers, a minesweeper, two ammunition ships, and an LST and damaged other ships. That night, a surface force comprising the battleship Yamato, the light cruiser Yahagi, and eight destroyers slipped out of Tokuyama for an attack on U.S. shipping off Okinawa. The mission was conceived in the kamikaze spirit, but it met with less success than previous ones. A plane from the Essex spotted the force on the morning of the 7th, and Task Force 58, though busy with a kamikaze attack, sent its planes north-westward to intercept. Before dark, they had sunk the Yamato, the Yahagi, and four destroyers. This was to be the last sortie of surface ships during the campaign, but it was realized that the graver menace of suicide planes had not ended.88

The emergency was such that Nimitz would have been justified in diverting the B-29’s from their primary mission even without the extraordinary powers vested in him by Norstad’s message of 31 March. On 8 April, LeMay sent 53 planes of the 73rd and 313th Wings against airfields at Kanoya, whence the enemy seemed to be launching his suicide attacks. Finding the primary targets completely obscured by clouds, the bombers hit the secondary, the city of Kagoshima, where they destroyed part of the residential district. Nimitz called for another strike on the 17th, and 134 B-29’s went out against six Kyushu airfields. Results were difficult to assess, but Nimitz expressed the belief that the mission greatly decreased the Japanese attack at Okinawa during the next eighteen hours.89

However, the enemy came back repeatedly. Between 6 April and 22 June he launched from Kyushu airfields ten large-scale kikusui

attacks totaling, as accurately as can be determined from Japanese sources, 1,465 kamikaze sorties. There were in addition 185 individual kamikazes flown from Kyushu and 250 from Formosa – a grand total of 1,900 suicide sorties, plus many standard escort sorties. In all, the Japanese sank 25 Allied ships while scoring 182 hits and 97 damaging near misses.90

The continuing threat demanded that every available weapon, including the B-29, be used to protect the invading forces. LeMay had informed Norstad of his diversion of 8 April, and on several occasions – 17 April, 28 April, and 5 May – the latter reiterated the earlier directive committing XXI Bomber Command to Nimitz’ use.91 Between 17 April and 11 May, the command devoted about 75 per cent of its combat effort to direct tactical support of the Okinawa campaign. In that period the B-29’s flew 2,104 sorties against 17 airfields on Kyushu and Shikoku.92 The fields, in order of frequency of attack, were: Kanoya, 15 attacks; Oita, 9; Kokubu, 9; Miyasaki, 8; Miyakonojo, 8; Kanoya East, 7; Tachiarai, 7; Izumi, 6; Kushira, 6; Nittagahara, 4; Usa, 4; Saeki, 4; Matsuyama, 4; Tomitaka, 3; Omura, 2; Ibusuki, 2; Chiran.93 In April, when the Japanese attacks were fiercest, XXI Bomber Command sent out heavy strikes, usually of well over a hundred planes drawn from all three wings. As the kamikaze raids diminished in size and as U.S. land-based air forces in the Ryukyus were built up,* demands on the B-29’s lessened so that during May only part of a single wing was assigned to each attack.94

The raids were designed not only to destroy airfield installations but to keep enemy fighters at home and hence out of the battle for Okinawa. Fighter opposition to the B-29’s fluctuated but was generally weak. During the third week in April, after the command had intensified its attacks, the Japanese increased their fighter forces in Kyushu from a combat strength of 75 single-engine and 22 twin-engine planes to an estimated total of 282, including 60 Navy interceptors. Apparently the enemy was funneling fighters through Kyushu to escort kamikazes going down to Okinawa. Later some of the short-range interceptors were sent back to Tokyo and indeed the enemy shifted his dwindling air forces so continuously that mission planning for Kyushu strikes after 30 April was based on a day-by-day estimate of the opposition that might be expected.95 Interceptions varied from none at all on 4 raids to 199 individual attacks on 27 April.

* See below, pp. 692-93.

B-29 crewmen reported a total of 1,403 such attacks and claimed 134 enemy planes destroyed and 85 probably destroyed. Antiaircraft was weak except at Kushira and the two Kanoya fields; only one plane was destroyed by flak. In all, 24 B-29’s were destroyed and 233 damaged.96

This was a light loss ratio; what the B-29’s accomplished in return (other than against enemy interceptors) is difficult to evaluate. The B-29’s went in at lower levels than in day strikes at heavily defended targets, at altitudes from 10,000 to 18,000 feet, and they frequently laid excellent bomb patterns on the runways, dispersal areas, and installations, But the enemy usually had warning enough to get his planes off the fields, and he was able to repair cratered runways in a matter of hours. After considerable experimentation with fragmentation and GP bombs, the command concentrated on the 500-pound GP, with fuzes varying from instantaneous to delays up to 36 hours, a combination which did hinder repairs.97 Best results were obtained against storage, maintenance, and repair facilities, but these affected future rather than current air operations. In general, the whole campaign was judged by Twentieth Air Force leaders to have confirmed their opinion that the B-29 was not a tactical bomber. Specifically, it was estimated that between 17 April and 11 May, 95 per cent of the enemy’s 1,405 combat sorties were flown on the same day that some of their key bases were being attacked by the Superforts.98

Yet the effort was not wholly wasted: the kamikaze threat was defeated by the combined efforts of all available forces; the B-29’s helped by keeping the enemy off balance, by making it difficult to plan and execute large and coordinated attacks such as the severe one of 6/7 April. Certainly the Navy was anxious that the B-29’s keep at the job of striking at the Kyushu fields even when it became clear that a complete neutralization could not be achieved.99

Nimitz called also on the VLR escorts of VII Fighter Command. The Iwo-based fighters had accompanied the B-29’s to Tokyo on 7 and 12 April* and had planned as their first independent mission a sweep over Atsugi airfield, the largest the Japanese had, for the 16th. In the emergency at Okinawa, Kyushu seemed more important, and after a last-minute change in plans the fighters headed for Kanoya. Because of the rush, pilots were not properly briefed, and they found poor visibility over Kyushu; only 57 of 108 P-51’s airborne were able

* See below, pp. 647-48.

to attack.100 On the 19th and 22nd the fighters worked over airfields on Honshu, then returned to Kyushu on the 26th as escort for a B-29 strike at the Kokubu field.101 Throughout the rest of the Okinawa campaign, and thereafter, the P-51’s periodically made sweeps over Empire airfields in search of planes and suitable installations to attack. The total P-51 effort was not very fruitful. Between 26 April and 22 June, there were 832 strike sorties, of which only 374 were effective. Claims included 64 enemy planes destroyed, 180 damaged on the ground, and 10 shot down in combat.102 The VII Fighter Command lost eleven planes in combat and seven from other causes; although the exchange was in its favor, there was nothing like the widespread destruction that had been desired. Weather was in part responsible. Four missions were wholly spoiled by heavy clouds, and for ten days early in May the fighters were weathered in at Iwo Jima. Enemy planes were hard to find. They rarely came up in force, as the low combat score indicates; only 145 were sighted aloft during May. Nor were they to be found in great numbers on the ground; the enemy’s constant shifting of planes from field to field and his increased use of dispersion, dummies, and camouflage left few fat targets. Pilots of the P-51’s often found it impossible to set fire to grounded planes, an indication that gas tanks had been drained.103

Nimitz released XXI Bomber Command from further support of the Okinawa campaign on 11 May with a message of thanks.104 The island was not officially declared secure until 2 July; organized resistance had lasted until 22 June and kikusui attacks from Kyushu had continued until that date.105 But by 11 May airfields at Yontan and Kadena and on Ie Shima had been put into shape to handle enough fighters* to justify the discharge of the B-29’s from their unprofitable chore, and LeMay returned to his unfinished business on Honshu.

Destruction of the Principal CitiesThe period of ICEBERG support had not been a total loss in respect to the strategic campaign. The target directive of 3 April had left aircraft engine plants in first priority but had stressed the need of continuing the March incendiary tactics against selected urban areas in Tokyo, Kawasaki, Nagoya, Osaka, and Yawata.† Between the Kyushu strikes, LeMay had been able to sandwich in a number of

* See below, p. 691.

† See above, p. 625.

medium-strength precision attacks against the aircraft industry and two large-scale night incendiary missions in the Tokyo Bay area. On 13 April, 327 B-29’s had dumped 2,139 tons on the arsenal district of Tokyo, northwest of the Imperial Palace. Fires burned out 11.4 square miles of that important industrial section, destroying arsenal plants that manufactured and stored small arms, machine guns, artillery, bombs, gunpowder, and fire-control mechanisms.106 Two nights later 303 B-29’s dropped 1,930 tons of incendiaries with equal success: areas destroyed included 6 square miles in Tokyo (mostly along the west shore of the bay), 3.6 square miles in Kawasaki, and 1.5 in Yokohama, which was hit by spillage. The two raids destroyed 217,130 buildings in Tokyo and Yokohama, 31,603 in Kawasaki. Japanese statistics on casualties at Tokyo vary widely, but in any event were much less frightful than those of the surprise raid of 9 March.107

On 10 April Col. Cecil E. Combs had recommended to Norstad that incendiary attacks be intensified immediately after V-E Day in an effort to bring about a quick surrender in Japan. The German surrender was announced on 8 May, and on the 11th Nimitz released the B-29’s from support of the Okinawa operation. Arnold immediately reconfirmed his target directive of 3 April, stressing, as Combs had suggested, the importance of concentrating the command’s efforts “in order to capitalize on the present critical situation in Japan.”108 LeMay needed no urging. His force had been augmented by the arrival of Brig. Gen. Roger M. Ramey’s 58th Wing, which had settled at West Field, Tinian, during April.” Willing to drive his crews in an effort to force Japan to surrender without an invasion which would repeat on a grand scale the horrors of Okinawa, LeMay inaugurated a month of heavy fire raids to finish up the job begun in March, while striking, as opportunity allowed, the top-priority precision targets.†

Target for the first raid of the new incendiary series was the northern built-up area of Nagoya, the vicinity around Nagoya Castle. This industrial-residential district included the No. 1 precision target, the Mitsubishi Aircraft Engine Works, as well as the Mitsubishi Electric Company, the Chigusa branch of the Nagoya Arsenal, and many lesser war industries. The mission was scheduled as a daylight strike, partly to confuse the Japanese defense, partly in the interest of accurate bombing; it was run on 14 May.109

* See above, p. 166.

† For the precision attacks, see below, pp. 646-53.

A total of 529 aircraft got off and 472 dropped 2,515 tons of M69’s on the target from. altitudes ranging from 12,000 to 20,500 feet. Bombing was supposedly downwind, but smoke blown across the area made it necessary for some planes to resort to radar. Residential sections under attack were only moderately built up, and although 131 separate blazes were identified, efficient work by the fire department kept some of these in check. Only one large conflagration got out of hand and that was stopped by a 200-foot firebreak near the castle. Even so, the numerous burnt-out areas when summed up amounted to 3.15 square miles; Mitsubishi’s No. Io engine works lost its Kelmur bearing plant and suffered other damage. Enemy reaction to the daylight attack was lively. In all, ten B-29’s were lost, one to flak, one to fighters, and eight to other causes; sixty-four were damaged. The B-29 crews claimed eighteen enemy planes destroyed, sixteen damaged, and thirty probables during the battle.110

The command went back to Nagoya on the night of 16 May in the last great area attack on that city. The target was the dock and industrial areas in the southern part of the city, location of the Mitsubishi Aircraft Works, the Aichi Aircraft Company’s Atsuta plant, the Atsuta branch of Nagoya Arsenal, the Nippoa Vehicle Company, and other numbered targets. The mission was planned as a low-level attack, with pathfinders pinpointing the aiming points with M47 incendiaries and the other B-29’s dropping M50’s, magnesium bombs suitable to the heavy structures in the area.111

The mission, when compared to that of the 14th, illustrates graphically the relative advantages of day and night tactics. Again it was a maximum effort, with 522 planes dispatched. Fewer planes – 457 as against 472 – were able to attack the primary target, but the low-altitude, individual approach allowed a heavier bomb load – about 8 tons as against 5.3 per plane – and the total weight dropped was 3,609. Because of smoke and thermal drafts, some planes had to bomb from levels much higher than those designated in the field orders and this tended to decrease accuracy. As usual in night attacks, opposition was weak; the three B-29’s lost were charged off to mechanical failures. Advantages and disadvantages, save in losses, about balanced out. The raid of the 16th started 138 fires which burned out 3.82 square miles. Mitsubishi’s No. 5 aircraft works was heavily damaged. Because of the progress of dispersal in the works, there was little change in production after the raid, though No. 5’s Mizuho plant,

still making engine cowlings, turned out only twenty units thereafter.112

This finished Nagoya as an objective for area attacks. Good targets remained in the city, and the command was to return six more times for precision attacks before V-J Day. But the industrial fabric of the city had been ruined in the earlier precision attacks and in the fire raids that had burned out twelve square miles of a total built-up urban area of about forty square miles. In all, 113,460 buildings had been destroyed, 3,866 persons had been killed and 472,701 rendered homeless. The displacement of workers aggravated the difficulties caused by physical damage and had an important effect on civilian morale.113

After a weeks respite, broken by a 318-plane precision attack,* XXI Bomber Command went back on the nights of 23 and 25 May for a final one-two knockout blow against Tokyo. In four previous area raids more than 5,000 tons of bombs had destroyed 34.2 square miles; 2,545 tons had been expended in precision attacks. The target for the 23rd was what JTG called Tokyo Urban Area No. 3, a district stretching southward from the Imperial Palace along the west side of Tokyo harbor that included both industrial and residential communities. The Emperor’s palace presented, as in other raids, a special problem. Its huge grounds served as a convenient checkpoint for navigators but constituted a most effective barrier against the spread of fires. Pilots, on orders from Washington, were briefed to avoid it “since the Emperor of Japan is not at present a liability and may later become an asset.”114

The 562 B-29’s airborne included 44 pathfinders; the tactics called for the familiar and successful combination of M47 and M69 incendiaries. There were relatively few aborts and strays, and 520 B-29’s got over target to drop 3,646 tons from altitudes ranging from 7,800 to 15,100 feet. The planned axis of attack had been designed to avoid the heaviest ground defenses but flak was intense; fighters were less effective. In all, seventeen B-29’s were lost (four to operational causes) and sixty-nine damaged. Weather was bad and bombardiers had trouble with smoke and the searchlights but were able to get enough bombs into the area to burn out 5.3 square miles.115

Two nights later 502 B-29’s returned to attack an area just north of that hit on the 23rd and nearer to the Imperial Palace. The new target included parts of the financial, commercial, and governmental

* See below, p. 650.

districts of Tokyo, as well as the familiar combination of factories and homes. Cloud coverage was light – 3/10 as compared to 9/10 on the 23rd – but cloud and smoke forced most of the bombardiers to loose by radar. Again the defense was rugged; crews reported the heaviest flak of the campaign, and the toll of losses from all causes amounted to twenty-six B-29’s destroyed and an even hundred damaged.116

The attack was, however, highly successful. Photos showed that the fires kindled by 3,262 tons of incendiaries had destroyed 16.8 square miles, the greatest area wiped out in any single Tokyo raid, though the attack of 9 March had accomplished almost as much with about half the bomb weight. In all, the six incendiary missions had gutted Tokyo, burning out 56.3 square miles, 50.8 per cent of the entire city area and slightly more than the sum of the designated target areas. Tokyo, like Nag as scratched from the list of incendiary targets.117

Yokohama came neat. Situated on the crowded west shore of Tokyo Bay and separated from the capital by Kawasaki, Yokohama, with a prewar population of 968,091, was Japan’s fifth largest city and her second largest port. It was an important shipbuilding and automotive center, and the target area included, in addition to installations devoted to those industries, plants engaged in oil refining, alumina processing, and the manufacture of chemicals. Yokohama had been hit by spillovers on various raids and had suffered especially in the Tokyo raid of 15 April, it had never been named as primary target.118

LeMay scheduled a daylight incendiary mission to Yokohama for 29 May. Relatively heavy losses in the recent Tokyo night missions had caused some concern in command headquarters; to avoid more serious casualties by day new tactics were devised. Field orders called for a high-altitude formation attack, with the groups crossing a time-control point on the Honshu coast at four-minute intervals. Aiming points were assigned to each wing according to a schedule of downwind bombing which was calculated to give the crews at least one drop in the target zone before it was obscured by smoke. As an antidote against the swarms of day fighters concentrated in the Tokyo Bay area, LeMay called on VII Fighter Command’s Iwo-based P-51’s; this would be their first assignment as escorts on an incendiary mission.119

The 517 B-29’s airborne found better weather than was usual in