Chapter 2: Alaska and Western Canada

The outbreak of war in Europe caused the United States to look to its Atlantic defenses but created little apprehension regarding the security of Alaska. General Staff planners believed that the undeveloped state of the Territory, poor means of communications, rugged terrain, and adverse climate made unlikely the operation of major land forces in Alaska and that air or land invasion of the United States via Alaska was not to be expected. Although the possibility of surprise aggression existed, they anticipated that any such enemy action would be minor and in all probability confined to the Aleutian Islands and the shores of the Gulf of Alaska. The key to the defense of Alaska, therefore, appeared to be the control of Kodiak, Sitka, and the Unalaska–Dutch Harbor area, where the development of naval bases was contemplated, and of Anchorage and Fairbanks, which could be developed as air bases and maintain a small, mobile air-ground team. Protected by a superior Pacific fleet, the bases could be defended by small Army garrisons and by aircraft capable of carrying effective action as far south as Ketchikan and as far west as Kiska.1

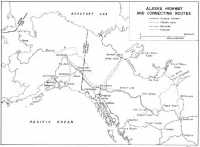

Strategy and the Development of Transportation

In line with this concept there was, beginning in mid-1940, a limited strengthening of Alaska’s defenses. A gradual build-up of Army forces at Anchorage and Fairbanks was undertaken, and small garrisons were established at Kodiak, Sitka, and Dutch Harbor, at covering airfields at Annette Island and Yakutat, and at Nome on the west coast of Alaska. Col. (later Lt. Gen.) Simon B. Buckner, Jr., was appointed commander of U.S. Army troops on 9 July 1940, and later headed the Alaska Defense Command (ADC), activated on 1 March 1941, with headquarters at Fort Richardson, Anchorage. The ADC came under the Western Defense Command, which like its predecessor, the Ninth Corps Area, embraced the U.S. west coast and Alaska. Expansion was accelerated somewhat as a result of the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 and renewed Japanese aggression in Southeast Asia, and by the end of the year Army strength in Alaska had reached 23,798.2

Meanwhile, construction was begun on an air line of communications between the United States and Alaska. Upon the recommendation of the Permanent Joint Board on Defense, established by the

United States and Canada in August 1940, work was begun on a chain of airfields extending across western Canada to Fairbanks. This construction program was nearing completion at the end of 1941.3

The defensive concept, predicated on U.S. naval supremacy, was rudely shaken by the Pearl Harbor attack. It was then feared that Japanese submarine action might endanger the sea lanes to Alaska and that enemy possession of bases in the Aleutians or on the shores of the Gulf of Alaska might cut the sea lines of supply from the U.S. west coast. At the same time, completion and expansion of the chain of airfields in western Canada and Alaska became an urgent necessity. To facilitate the operation and supply of these airfields, and to provide an emergency land route to Alaska in the event of enemy interference on the sea lanes, the War Department undertook the construction of the Alaska Highway. Also, surveys were made to determine the feasibility of building a railroad via the Rocky Mountain Trench from Prince George, British Columbia, to Fairbanks; the Canol Project, designed to tap western Canadian oil resources to supply aviation and motor fuel to western Canada and Alaska, was initiated; and studies were made regarding the development of river and winter road routes to supply stations that would be cut off in the event the Bering Sea or the Gulf of Alaska or both were denied to U.S. shipping.4

While the use of alternate routes and resources was under consideration, steps were being taken to maintain and expand the supply of Alaska by water. As a safety measure, vessels were routed via the Inside Passage, formed by the islands of southeast Alaska, to Cape Spencer, where convoys were formed for onward movement across the open sea to stations in central and southwest Alaska and beyond. To ease the pressure on Seattle, the port of embarkation for Alaska, a subport was opened at Prince Rupert, British Columbia, and in an effort to relieve the shortage of ocean-going vessels the Alaska Barge Line was established to carry cargoes from Seattle and Prince Rupert via the Inside Passage to Juneau, and later to Excursion Inlet, for transshipment westward on ocean-going vessels.

As construction forces began work on the Alaska Highway and other western Canadian projects, the barge line also carried supplies to Skagway, Alaska, the ocean terminal connected by the White Pass and Yukon Railroad with the highway at Whitehorse in the Yukon. In the fall of 1942 Skagway was activated as a subport of Seattle, and to expedite deliveries to Whitehorse the Army leased the antiquated rail line. To command all U.S. Army activities in western Canada and the extension of those activities into Alaska, including the White Pass and Yukon Railroad and the Alaska Highway, the Northwest Service Command (NWSC) was established in September 1942. Col. (later Brig. Gen.) James A. O’Connor assumed command and set up his headquarters at Whitehorse.

In Alaska, meanwhile, expansion of defensive garrisons proceeded as far as the limited shipping permitted. Existing bases were strengthened, new ones established, and new airfields constructed. In early 1942, to cover Dutch Harbor, sites for airfields were garrisoned at Umnak Island in the Aleutians and at Cold Bay in the Alaska Peninsula. Other stations activated before June included Cordova, Valdez, and Juneau in southeast Alaska, and Naknek off Kvichak Bay.5

Even as efforts to gird Alaska’s defenses moved forward, the Japanese launched a two-pronged attack against Midway and Dutch Harbor. The repulse of the enemy at Midway (3-6 June) removed the threat to the U.S. west coast and the Hawaiian area and helped restore the balance of naval power in the Pacific. The Dutch Harbor attack (3-4 June) proved diversionary and ended with the withdrawal of Japanese forces and their occupation of Kiska and Attu Islands in the western Aleutians. These enemy bases lacked the strength to threaten seriously Alaska’s security or to disrupt the sea lanes in the Bering Sea and the Gulf of Alaska.

After the Dutch Harbor attack, the Nome garrison was strengthened and Army forces were stationed in the Bristol Bay and Kuskokwim Bay areas, in the Pribilof Islands, and at various points in the interior of Alaska. An advance along the Aleutian chain was begun in August 1942 with the occupation of Adak Island, which was followed in January 1943 by unopposed landings on Amchitka Island. Both Adak and Amchitka were developed as important forward bases, from which the Japanese-held islands were subjected to increasingly heavy air attack.

As a result of these military developments, there came into existence a large number of scattered garrisons dependent on water transport and, with the exception of installations served by the Alaska Railroad and the Richardson Highway, lacking connections with each other. By the fall of 1943 there were in Alaska twenty-eight ports, forty main posts or garrisons, and over seventy locations where troops were stationed.6

The expansion of defensive installations was accompanied by several notable improvements in the field of transportation. Additional port facilities were constructed at Seward and Dutch Harbor. Adak, a barren island when occupied, was developed into a port handling over 100,000 measurement tons per month. The Alaska Railroad’s civilian force was augmented by a railway operating battalion in the spring of 1943, and a rail extension was completed from Portage Bay to the newly developed port of Whittier, giving the railroad a new and more convenient port of entry.

Meanwhile, the possibility of utilizing Alaska as an overland supply route to Siberia and/or as a base for large-scale offensive operations had been explored. In the latter part of 1942 the idea of a railroad from Canada to Alaska was revived, together with a rail extension and pipeline from Fairbanks to a port on the Seward Peninsula. Also, plans were made for the development of river and winter road routes from Whitehorse to Fairbanks and thence along the Yukon River to Alaska’s west coast, and for a similar project along the Kuskokwim River. Planning for the Alaska Highway called for the delivery of

as much as 200,000 tons monthly to Fairbanks from the Dawson Creek and Whitehorse railheads. The Canol Project, originally intended to produce crude oil at Norman Wells in the Northwest Territories and carry it to Whitehorse by pipeline for refining, was expanded to include a distribution pipeline system extending from Skagway to Whitehorse and from Whitehorse south to Watson Lake and north to Fairbanks and Tanana. The chain of airfields was expanded, intermediate airfields were placed under construction, and in September 1942 an air ferry system for the delivery of lend-lease aircraft to Siberia was established along the airway.7

Most of the plans for large-scale transportation operations were soon abandoned or considerably deflated. By early 1943 it was apparent that neither the plan for an overland supply route to Siberia nor that for major offensive action based on Alaska would soon materialize. At the same time, the continued availability of the sea lanes and the improving shipping situation not only made it possible to meet the needs of the forces in Alaska and western Canada more adequately, but also to provide for the expulsion of the Japanese from the Aleutians. The capture of Attu in May and the unopposed landings on Kiska in August completed this phase. Thereafter, steps were taken to reduce Alaska to a static, defensive garrison.

These events made unnecessary the development of alternate overland routes. Although an Engineer survey had upheld the feasibility of constructing a trans-Canadian Alaska railway, the project had been unfavorably considered by the War Department in November 1942 because of the time and expense involved. Inland waterways were developed only to a limited extent and winter roads were used only in emergencies. The Alaska Highway, opened as a pioneer road in November 1942 and substantially completed as an all-weather highway in October 1943, was used to deliver only a token amount of materiel in Alaska beyond Fairbanks, although it proved valuable in supplying airfields and Army and civilian construction forces along the route.8

The end of the Aleutian Campaign brought a marked reduction in Alaska’s transportation requirements. Construction was curtailed, many garrisons and airfields were inactivated or placed in a caretaker status, excess supplies were evacuated or redistributed to remaining centers of activity, and surplus troops were returned to the United States for deployment to more active theaters. On the administrative side, the ADC on 1 November 1943 was divorced from the WDC and established as the Alaskan Department, an independent command reporting direct to Washington.

With the exception of Canol, which was pressed to completion as a measure to relieve the world-wide oil and tanker shortage, western Canadian projects moved

from a construction to a maintenance phase in early 1944.9 As a part of a general reorganization calculated to facilitate the transition, a command-wide Transportation Section was established headed by Lt. Col. Harley D. Harpold. Whereas operations in NWSC had previously been characterized by a lack of centralized control and coordination of the available means of transportation, under the new set-up the Transportation Section exercised centralized movement control and other traffic management functions. At the same time, operations were decentralized to five transportation districts, which operated under policies and procedures formulated by the Transportation Section. The resultant improved planning and coordination of movements and more efficient use of transportation contributed to the orderly reduction of the command.10

When Canol’s production and refining facilities were abandoned in March 1945, the last major activity in western Canada came to a close. Activities that were continued—maintenance of the Alaska Highway, signal communications, and distribution pipelines; supply of the airfields; and operation of the port of Skagway and the White Pass and Yukon Railway—were rapidly reduced to minor proportions. In June 1945, when NWSC was discontinued and its duties were turned over to the Sixth Service Command, there were less than 1,600 military personnel in western Canada.11

On V-J Day, Alaska was a static defensive area with a military strength of approximately 36,000. The supply of Alaska still depended on water transportation, supplemented by a small amount of cargo and a considerable number of passengers carried by air. The availability of the sea lanes and shipping made it uneconomical to supply Alaska in any other fashion, but the Alaska Highway and associated projects added considerably to the area’s potential for defense in the uncertain years ahead.

Evolution of the Transportation Organization in Alaska

The creation of a large number of isolated garrisons in Alaska resulted in the development of a decentralized command structure. Since extremely limited communications between stations made impossible an orthodox supply system whereby depots were organized in depth with rail and road nets leading to the forward areas, post commanders were made responsible for the supply as well as the defense of their installations. Exercising command and supply functions normally performed by higher headquarters, they requisitioned most categories of supply directly on the Seattle Port of Embarkation, maintained reserves of stocks, and

assumed administrative and operational control over all service and ground troops. Each post tended to become a self-contained installation subject to a minor degree of coordination from ADC headquarters.12

Before the Pearl Harbor attack, Army transportation operations were confined largely to the ports. In August 1941 there was a total of six Quartermaster officers serving as Assistant Superintendents, Army Transport Service, one each located at Seward, Sitka, Dutch Harbor, Chilkoot Barracks, Annette Island, and Yakutat. These officers handled ATS functions in addition to their other duties. Labor was provided by civilians, where available, or by troops detailed by the post commanders.13

The first command-wide ATS organization emerged shortly after Pearl Harbor. With the expansion of defensive garrisons, the Army Engineers chartered floating equipment from canning firms and other commercial interests in order to move construction personnel and materials to new stations and to handle lighterage and other harbor activities. The Officer in Charge of Alaska Construction was made responsible for the operation of this equipment and accordingly was designated Superintendent, Army Transport Service.

Effective 1 July 1942, the ATS was divorced from the Engineers and placed under the administrative jurisdiction of the ADC Quartermaster Section. An ATS superintendent was assigned, assuming responsibility for all floating equipment formerly under the Engineers, and arrangements were made to bring all harbor boats in ADC under his control. Toward the end of the year a Transportation Section was established on the special staff of ADC headquarters at Fort Richardson, and the ATS superintendent was made part of this section.14

The ATS superintendent was primarily a staff officer responsible for coordinating vessel movements within the command, the control of ports remaining a function of post commanders. Consequently, there evolved during 1942 a large number of widely distributed, unconnected or loosely connected ATS units, known in ADC as “outports.” Lacking authorized Tables of Organization, the typical ATS outport was staffed by a few military and civilian personnel furnished from local sources. Port labor was sometimes provided by organized port companies, but more often work was performed by details from tactical troops. ATS units, port companies, and other personnel were under the control of the post commanders.

Improvisation and the use of garrison troops provided relatively efficient operation of Alaskan ports, but by late 1942 the growing volume of shipping made it necessary to increase outport staffs, bring in qualified transportation personnel, and provide for a larger degree of coordination in shipping and port activities. In December 1942 the War Department approved an ADC request for an allotment of forty-four officers, including an ATS superintendent qualified in shipping and harbor operations, and assistant superintendents and other officers to supervise

cargo handling and harbor craft operation and maintenance at the outports.15

About this time General Buckner placed a request with the War Department for a chief of transportation for ADC. In January 1943 Colonel Noble, who had commanded the 12th Port at Churchill, Manitoba, was selected by the Chief of Transportation in Washington. Upon arrival at ADC headquarters, Noble was disappointed to find that he was not to assume over-all direction of transportation operations. Brig. Gen. Frank L. Whittaker, newly appointed Deputy Commander, ADC, responsible inter alia for logistical operations, believed that water transportation was so important that it would require Noble’s full attention. Consequently, Noble served solely as ATS superintendent. Maj. (later Col.) Reuben W. Smith, heading the ADC Transportation Section, was retained to deal primarily with rail operations. In practice, both men acted as staff officers to General Whittaker, who exercised general supervision over transportation operations.

As Superintendent, ATS, Noble gave the outports a larger degree of guidance and instituted measures to control the flow of traffic. ATS outport units at twenty-three ports were expanded and revitalized; War Department approval of manning tables was obtained for ATS outport headquarters, harbor craft detachments, marine way units, and maintenance platoons; marine repair facilities were placed under construction at Adak, Seward, and Fort Glenn and a floating repair shop was secured from Seattle; maintenance platoons were assigned to the principal ports; and training schools for harbor boat personnel were activated. By August 1943 the ATS was beginning to take its place as a highly important operating unit of ADC.16

Despite his success in effecting considerable improvement in the ATS organization, Colonel Noble was dissatisfied with his status in the command. He found that his authority was not only restricted by General Whittaker’s supervision, but also by the supervision exercised by post commanders, several General Staff officers, the ADC Transportation officer, officials of the WDC, and the Seattle Port of Embarkation. His basic difficulty was that of developing an integrated ATS organization when control of ports was decentralized to officers appointed by and responsible to post commanders. Noble could give technical guidance to Assistant Superintendents, ATS, but could exert influence over port commanders only through General Whittaker. Although Whittaker was willing to correct situations where port commanders did not permit assistant superintendents to function properly, he insisted that the ATS superintendent should not infringe on the control of ports by post commanders.17

Noble advocated the establishment of a centralized transportation organization

exercising direct control over shipping, port, rail, and other transportation activities. Instead, ADC in August 1943 issued directives that made some progress in centralizing ATS activities, but that in other respects proved disappointing to him. ATS was made a separate command and was designated the responsible agency for the management, operation, and maintenance of all vessels in Alaskan waters and for their routing and berthing. The assistant superintendents and the units under their control, including outport headquarters, harbor craft detachments, and marine way and maintenance units, were placed under the ATS superintendent for technical direction, but remained under the administrative and operational control of post commanders. At the same time, the ATS superintendent was removed from the ADC special staff, and the ADC Transportation Section was announced as the special staff agency dealing with transportation matters. Control of troop and cargo movements was given to G-3 and G-4 respectively, and post commanders were authorized to use, without reference to ADC headquarters, any transport facility serving their posts.18

The creation of an independent ATS was a step forward, but Noble maintained that he had been denied essential functions, which were retained by various members of the General Staff and the ADC transportation officer. Disappointed because he had never been permitted to function as ADC chief of transportation and believing that the ATS had grown into an efficient organization only in the face of “continual interference” and “opposition to policies which would allow the Superintendent, ATS to establish and exercise normal prerogatives,” Noble was convinced that his usefulness in Alaska had ended.19

Colonel Noble was transferred from Alaska and was succeeded in September 1943 by Col. Joe Nickell, a Field Artillery officer who had been port commander at Adak, Attu, and Shemya Islands. At that time Transportation Corps strength in Alaska attained a wartime peak. On 1 October there were 1,917 troops and several hundred civilians serving with ATS and outport headquarters, harbor craft detachments, marine way units, and maintenance platoons. In addition, four port battalion headquarters and seventeen port companies, aggregating 4,000 men, were stationed at the major year-round ports, and 1,168 railway troops were working on the Alaska Railroad. Regardless of deficiencies, much progress had been made in expanding transportation operations in the command.20

Under Colonel Nickell the conflict between centralized and decentralized control of port operations was resolved. The functions of port commander and Assistant Superintendent, ATS, were combined and assigned to experienced Transportation Corps officers wherever possible. This was eventually accomplished at all the major western Aleutian ports except Amchitka, where an Infantry officer detailed to the Transportation Corps had done an excellent job and was retained. At ports with an almost purely transportation

mission, such as Whittier, Seward, and Nenana, Transportation officers were assigned either as post commanders or executive officers to the commanders. In this manner, the Superintendent, ATS, was able to give centralized direction to a decentralized operation.21

Integration of transportation functions was also accomplished at ADC headquarters. Retaining his position as ATS superintendent, Nickell was appointed Chief of Transportation and Traffic Manager, Alaskan Department, in March 1944, assuming responsibility for the control and coordination of all transportation facilities and military traffic under the jurisdiction of the Commanding General, Alaskan Department, and for arrangements for air movement of personnel and cargo. Colonel Smith, previously transportation officer on the Alaskan Department’s special staff, became assistant chief of transportation. When motor transport on the Alaskan portion of the Alaska Highway was transferred to the Alaskan Department in June 1944, Nickell took control of this activity, and arranged for commercial truckers to handle the minor traffic flowing from Fairbanks to the Alaskan-Canadian border.

Water transportation remained Colonel Nickell’s chief responsibility, including port operation, intratheater shipping, and the operation, maintenance, and repair of floating equipment. Motor transportation activities were negligible, and after much delay most railway troops were evacuated in the spring of 1945. At the war’s end, Transportation Corps strength in the Alaskan Department, including the Transportation Section and ATS headquarters, fifteen outport headquarters, harbor craft personnel, ship repair and maintenance units, supply personnel, and port troops, was approximately 3,000 officers and enlisted men and 500 civilians—a sizable number when compared with the small total military establishment in Alaska.22

Shipping—The Key to the Supply of Alaska

From a transportation point of view, Alaska was not a peninsula but an island linked with the continent by sea and air. Since the Territory produced little locally for its own support, the military as well as the civilian population depended heavily on shipping from the U.S. west coast. The supply of the Army in Alaska was initially maintained by a small fleet of government-owned and government-chartered vessels operated by the ATS at the San Francisco Port of Embarkation. In the first year of the build-up, ending 30 June 1941, that port shipped approximately 210,000 measurement tons to Alaska. Most of this cargo was delivered to Seward for local use and for rail distribution to bases under development in the Anchorage–Fairbanks area, with small tonnages going to Kodiak, Sitka, and other southeast Alaskan ports. The nine vessels in service in July 1941 were of small capacity, had seen long service, and in most instances had a top speed of below ten knots.

Seattle was established as a subport of San Francisco in August 1941, and assumed responsibility for shipments to Alaska. In the last six months of the year the ATS fleet was increased, and approximately 330,000 measurement tons, des-

tined largely for Alaska, were shipped from Seattle. Building materials for the Corps of Engineers made up 60 percent of this tonnage.23

The attack on Pearl Harbor greatly complicated shipping problems. The necessity for routing vessels through the Inside Passage and convoying them forward from Cape Spencer lengthened sea voyages and slowed deliveries. The number of Alaskan stations served by Seattle increased from 12 in December 1941 to 38 in October 1942. Most destination ports had extremely limited facilities, so that cargo discharge was slow and ships’ turnaround time unduly long.

In the first months after Pearl Harbor the Army, engaged in strengthening its defenses in other vital areas and in securing the lines of communications to the Philippines and Australia, could make few additional vessels available for the Alaska run. In January 1942 the ATS at Seattle, which had been made a primary port of embarkation independent of San Francisco, was operating six government-owned and ten bareboat-chartered vessels capable of delivering 55,000 measurement tons a month. Since 106,000 measurement tons a month plus space for personnel were needed, supplies began to pile up at Seattle.24

When the local War Shipping Administration (WSA) representative attempted to effect the return to their owners of ships on bareboat charter to the ATS, Seattle, the Army objected and a lively controversy ensued. The Western Defense Command proposed that all vessels engaged in the supply of Alaska be placed under military control, but the War Department considered this impracticable. Instead, Transportation Corps and WSA officials in Washington arranged a compromise whereby vessels already under bareboat charter to ATS would remain in that status; other commercial vessels in the Alaskan service would continue to be manned and operated by their owners, and WSA would allocate them to the Army, the Navy, or civilian agencies as required. Those ships allocated to the Army were loaded and directed to their destinations by the ATS.25

The transports owned and chartered by the Army plus those allocated to it by WSA were insufficient to carry the burden. The situation grew serious after April 1942, as demands arising from construction work on the Alaska Highway and other western Canadian projects were added to Alaskan requirements. To alleviate the shortage, six vessels were diverted from other services to the Alaskan run. In addition, the ATS at Seattle arranged for fishing vessels to carry Army cargo to southeastern Alaskan ports upon their departure for fishing banks in the area; chartered a few Canadian vessels and available space on commercial vessels; utilized tugs, barges, and vessels unsuitable for ocean duty to deliver cargo to Inside Passage ports; and arranged for naval vessels to carry some Army cargo. In July

1942 Alaska Barge Line operations were instituted to deliver materials from Seattle and Prince Rupert to Juneau for transshipment westward on ocean-going vessels. In this fashion, water shipments to Alaska and western Canada were increased from 50,347 measurement tons in December 1941 to 234,287 measurement tons in October 1942. In the same period over 64,000 troops were transported by water to Alaskan and western Canadian stations.26

By November 1942, twenty-nine U.S.-owned and U.S.-chartered vessels in the Alaskan service, supplemented by barges, fishing vessels and WSA-allocated ships, were meeting minimum requirements, but they did not deliver sufficient tonnage to overcome the general shortage of housing, construction materials, and other supplies. With shipping barely adequate for defensive purposes, tactical operations were possible only after careful logistical planning. When Adak was occupied in August 1942, shipping was phased so that vessels did not arrive faster than they could be discharged. Later in the year, the War Department’s diversion of several vessels from the Alaskan run to meet lend-lease commitments to the Soviet Union caused the cancellation of plans to occupy Tanaga Island in the Aleutians. Most of this shipping was soon replaced, but the incident indicated the narrow margin on which the Army operated in Alaska.27

During the first half of 1943, the shipping situation steadily improved. Port facilities at Seattle and Prince Rupert and in Alaska were expanded, and the worldwide shipping shortage eased somewhat. In May approximately a hundred Army transports and commercial vessels were on the Alaska run, as well as tugs, barges, and other floating equipment.28 Water de liveries attained an all-time high in July, when Seattle and Prince Rupert shipped 364,106 measurement tons to Alaska and western Canada. In this period shipping was also made available for new tactical operations, which culminated in the Kiska landings in August 1943.

With the ensuing curtailment of activities and the consequent reduction of military strength in Alaska and western Canada, water shipments fell off steadily, averaging about 54,000 measurement tons monthly in late 1944. By the end of the year, Army troops in Alaska had been reduced from a peak of 150,000 in August 1943 to 52,000, while military personnel in NWSC had decreased from 24,000 to 2,400. At the war’s close, water deliveries were on the order of 30,000 measurement tons a month. Vessels from the zone of interior were then calling at six major Alaskan ports, from which passengers and cargo were transshipped to other stations by vessels under theater control.29

Development of Subports for Seattle

The build-up of Alaskan defenses following the Pearl Harbor attack was retarded by congestion at the Seattle Port of

Embarkation as well as the shipping shortage. The rail net leading into Seattle, the terminal facilities, and the port personnel were inadequate immediately to handle the accelerated movement of troops, supplies, and equipment. In an effort to relieve the burden on Seattle and to increase the lift to Alaska, a number of subports were established in western Canada and southeastern Alaska.

The first and most important of the sub-ports was Prince Rupert, British Columbia, situated almost 600 miles north of Seattle at the western terminus of the Canadian National Railway. With Canada’s consent, the subport was officially activated on 6 April 1942, for the purpose of shipping to southeast Alaskan stations cargo that could be routed to it by rail from eastern and central United States as well as a smaller amount delivered by vessel, barge, and rail from Seattle. Immediately available at Prince Rupert were leased docks capable of berthing three vessels, a transit shed, limited open and closed storage space, and a small group of two officers and twenty-six civilians who had handled the salvage and reshipment of the cargo of a transport grounded nearby. Steps were taken to augment port personnel and construct additional port facilities, and tugs, barges, and small Canadian vessels were chartered or obtained from Seattle to supplement the ocean-going vessels operating out of the port. Installations to handle ammunition were leased at Watson Island, twelve miles from Prince Rupert, and a staging area was placed under construction three miles beyond at Port Edward.30

Prince Rupert’s development was slower than expected, the port shipping forward less than 50,000 measurement tons and fewer than 3,000 troops in its first ten months of operation. The scarcity of local labor and materials retarded construction, and a shortage of floating equipment limited traffic. Operations were further handicapped in the winter of 1942–43 by congestion on the Canadian railways, which were overtaxed with supplies for the Alaska Highway and Canol as well as for Prince Rupert. In the absence of centralized traffic control, freight car movements were un-coordinated, and agencies concerned, both contractor and military, diverted and unloaded cars without regard to consignee or ownership of the freight. As a result, individual cars meandered along the line all the way from Waterways to Edmonton, Dawson Creek, and Prince Rupert, before they were either unloaded or transshipped. Some semblance of order appeared with the establishment in November 1942 of a Rail Regulating Station at Edmonton, but the tie-up could not be materially eased until March 1943, when a temporary embargo was placed on rail shipments into Canada.31

Operations began to improve in the late spring and summer of 1943 as rail congestion was reduced and construction progressed. Three new berths for vessels and three barge berths were completed, a dock apron, a transit shed, and storage space were added, and by midyear housing for 3,000 men was provided at the Port Edward staging area. With increased facilities available, Prince Rupert in March

1943 was assigned direct responsibility for the supply of Alaskan stations southward from Yakutat, including the Excursion Inlet barge terminal, and for water deliveries to forces in western Canada through Skagway. Port traffic increased steadily, hitting a peak in July 1943, when Prince Rupert shipped forward approximately 95,000 measurement tons, received about 47,000 measurement tons by rail and water, and handled over 12,600 military and civilian personnel arrivals and departures. Staffed by some 3,900 troops and civilians, the subport then had operating responsibility for 17 cargo vessels of 60,000 measurement tons capacity, 17 tugs, and scows with a capacity of 22,000 measurement tons.

Water shipments dropped to 38,518 measurement tons in August and continued to decrease despite the fact that Prince Rupert was given the added responsibility in December of supplying the stations served by the Alaska Railroad. While the curtailment of activities in Alaska and western Canada materially reduced the port’s value, the fact that Seattle was being groomed to play a major part in support of Pacific operations made advisable Prince Rupert’s retention as a reserve port ready to take over the entire supply of Alaska should Seattle become overburdened. In the summer of 1944 the port was reduced in strength and nonessential installations were placed on a stand-by basis. Prince Rupert continued in operation as an outport of Seattle throughout the war, shipping to Alaska and the Pacific Ocean Areas such supplies as could economically be laid down at the port.32

Like Prince Rupert, the Juneau and Excursion Inlet subports had their genesis in the shipping crisis of early 1942. Alarmed by the growing backlog of construction materials needed for the development of new bases in southwestern Alaska, the district engineer at Seattle proposed making large-scale barge deliveries via the Inside Passage to a terminal in the vicinity of Cape Spencer, where cargo would be transferred to ocean-going vessels for westward delivery. By cutting in half the voyages of transports, the barge operation would greatly increase the amount of cargo they could deliver to Alaska.

The plan was adopted by Western Defense Command and received War Department approval in May 1942. The Army Engineers thereupon undertook a survey to determine the best site for a terminal and the construction required. The Seattle port commander, who was assigned responsibility for the project’s development, formulated plans for a barge line designed ultimately to deliver 150,000 measurement tons a month and set up an interim operation to Juneau with craft locally available.33

The transshipment operation at Juneau contributed little to the supply of Alaska, principally because of limited port facilities and the slow development of the barge line. The production of necessary new floating equipment took time, and in the meantime only a limited number of craft could be secured through charter,

lease, and purchase. In October 1942 the barge line was hauling about 18,000 tons monthly from Seattle and Prince Rupert, for delivery to Skagway and other Inside Passage ports as well as Juneau. Moreover, increased water deliveries direct to Alaskan destinations in the latter part of 1942 eased the pressure for augmentation of the barge line, and the lion’s share of newly acquired floating equipment was allotted to ADC for lighterage and other operations in Alaska. These developments, together with diversions of craft to tactical operations in the Aleutians, accidents, and equipment breakdowns, caused deliveries to Juneau to remain far below those originally planned.34 From its activation in July 1942, when the first shipments of cargo arrived by barge, the Juneau subport received only 50,548 measurement tons by barge, Army transport, and commercial vessel from Seattle and Prince Rupert, and shipped forward only 32,716 measurement tons to destinations from Yakutat westward.35

Meanwhile, Excursion Inlet, a barren site located at the head of the Inside Passage had been selected for the planned barge terminal. Construction, begun in September 1942, was sufficiently advanced by the following spring to warrant the transfer of most transshipment operations from Juneau. Activated on 22 March 1943, Excursion Inlet received approximately 275,000 measurement tons during the year, much of it by barge, small Canadian vessels, and other ships unsuitable for long ocean voyages, and shipped forward about 156,000 measurement tons to Alaskan destinations as far west as Attu. At the end of 1943 some 7,000 troops and 180 civilians were on duty at the subport, and construction completed included two 1,000-foot wharves, two 4,000-foot barge extensions, two oil docks, cold storage and marine repair facilities, housing, thirty miles of road, and a station hospital.36

The transshipment operation was not expanded beyond this point. The shift of military strength in Alaska to the Aleutians reduced the savings in ships’ turnaround time that could be effected by using Excursion Inlet. Moreover, it was more important to furnish employment for the civilian labor pools at U.S. west coast ports such as Seattle, which was not then being used to capacity, than to continue operation of a port of limited value with troop labor. By April 1944, when the War Department ordered the subport’s discontinuance, cargo arrivals had virtually ceased, accumulated cargo was being cleared, and military strength was in the process of reduction.37 Salvageable materials were then shipped back to the United States, and a small caretaker detachment was left behind at the installation, which was formally inactivated in January 1945.

Although over-all barge deliveries cannot be segregated in the available port statistics, it was estimated that 240,000 measurement tons were shipped by barge from Prince Rupert and Seattle between October 1942 and August 1943. In the fall

of 1943 barge operations were accounting for a substantial proportion of deliveries to Excursion Inlet and for approximately 22,000 measurement tons a month carried to Skagway and other southeastern Alaskan ports.38 But their importance was already declining. After the close of transshipment activities at Excursion Inlet, barge operations were limited chiefly to small-scale deliveries from Prince Rupert to Skagway and other southeastern Alaskan destinations.

Unlike Juneau and Excursion Inlet, which were transshipment ports for the supply of Alaskan stations, Skagway was developed as an ocean terminal for U.S. military and civilian forces in western Canada.39 Located at the head of the Lynn Canal and connected by rail with the Alaska Highway, Skagway began receiving cargoes in the spring of 1942 for the supply of construction and other forces served out of Whitehorse. By the fall of the year Skagway was becoming badly congested. Available military and civilian labor was insufficient, and the narrow-gauge railroad and its wooden two-berth dock were antiquated, poorly equipped, and extremely limited in capacity.

To cope with the situation, Skagway was established as an Army subport of Seattle in September 1942. Work was begun on dock improvement, cargo-handling equipment arrived, and port troops were assigned to handle dock operations, warehousing, and carloading. At the same time, the Army leased and took over operation of the rail line. Improvement was immediate, but the onset of severe winter weather in December again curtailed port operations, and the small volume of tonnage discharged from ships and barges piled up on docks and in storage areas because of interruptions in rail service.

With the moderating of the weather the upswing in port traffic was resumed, and in May 1943 Skagway discharged approximately 30,000 weight tons, over four times its September 1942 performance. By this time two additional vessel berths, new barge grids, and more storage space were available, port personnel had been increased, and improved rail operations had cut down backlogs at the port. Traffic at Skagway reached a peak in August 1943, with the discharge of approximately 58,000 weight tons (estimated at 90,000-100,000 measurement tons).

Skagway was transferred from Seattle’s control on 1 September 1943, becoming a port of debarkation under the Northwest Service Command. During the remainder of the year port activity declined sharply as construction projects in western Canada neared completion. The subsequent evacuation of civilian contractor employees and equipment took up some of the slack, but this failed to halt the general downward trend of port traffic. With the general curtailment of NWSC activities in 1944, the port was reduced in strength. Later in the year, in order to make maximum use of the personnel available and to provide unified direction to the interrelated port and railroad activities, both operations were consolidated and placed under an Army officer

designated general superintendent. The small continuing traffic was handled by a combination of military and civilian personnel, and provision was made for the eventual replacement of all Army troops by civilians.40

The Alaskan Ports

During the three years of the Alaskan build-up ending with the occupation of Kiska iii August 1943, there evolved a large number of scattered and isolated ports possessing limited facilities and often subject to adverse climatic conditions.41 In southeastern and central Alaska, the ports were generally ice-free, but handicapped by excessive fog and rain. North and northwest of Kodiak, the ports were icebound seven to eight months in the year and had to be supplied entirely during the summer season. With the exception of Bethel, which could handle ships drawing up to eighteen feet of water, these ports were rendered unsuitable for dock operation by rough seas, high winds, and shallow and rocky approaches. Ships had to be discharged by lighterage since they had to anchor twelve miles offshore at Naknek, six miles at Port Heiden, and two miles at Nome. The Aleutian chain, stretching 1,200 miles westward from the Alaska Peninsula, was ice-free, but with the exception of Dutch Harbor the ports were barren, wind-swept, and sparsely inhabited. Umnak, garrisoned in early 1942, lacked harbors and had to be supplied by barge from Chernofski Harbor, twelve miles to the southwest. As other Aleutian bases were occupied, it was necessary to start from scratch, lightering in troops, equipment, and supplies, constructing docks, sorting sheds, warehouses, and other base facilities, and eventually converting from lighterage to dock operations.

At most Alaskan ports, the scarcity of civilian labor made necessary the extensive use of military personnel for handling cargo. In the absence of trained port units, Engineer and tactical troops were employed. Army port companies were eventually brought in and one or two were assigned to each of the larger ice-free ports, but these units were often heavily supplemented by tactical troops, particularly at the Aleutian ports. At the icebound and the smaller ice-free stations, port labor continued to be performed largely by garrison troops. Some assistance was provided through continuance of a peacetime practice of ships engaged in the Alaskan trade, since crew members on both commercial vessels and Army transports acted as winchmen and longshoremen and performed other duties incident to cargo discharge and loading.42

The principal prewar port was Seward. Located at the southern terminus of the Alaska Railroad, it was the port of entry for Army and civilian goods for Anchorage, Fairbanks, and other points served by the rail line. Cargo was discharged by civilian longshoremen over an old railroad-owned dock capable of berthing two ocean-going vessels. Seward was able to handle cargoes for the initial build-up of the Anchorage-Fairbanks area, but with the increased traffic following Pearl Harbor the Army had to construct a new two-berth dock and bring in port troops. In

April 1943 the three port companies on duty at Seward, together with civilian longshoremen, discharged approximately 38,000 measurement tons of Army cargo.

Despite the improvements, Seward was not retained as the main port of entry for stations on the rail belt, because the mountainous southern section of the rail line impeded traffic moving northward.43 In May 1943 a rail cutoff was completed extending from Portage junction, sixty-four miles north of Seward, eastward to Whittier on Prince William Sound. Virtually all Army cargo was then routed through Whittier, which commenced operations on 1 June 1943 with a newly constructed Army dock capable of berthing two ocean-going vessels and adequate railway yard and terminal facilities. Whittier handled its peak traffic in July 1944, when two port companies discharged or loaded 53,500 measurement tons. When the war ended the port was still active, but rarely handled more than 10,000 measurement tons a month.

Anchorage, the third port on the Alaska Railroad, was the site of the largest military station on the Alaskan mainland. Unfortunately, it was icebound six to seven months of the year, and during the open season operations were handicapped by tides of unusual height and bore. The Army rehabilitated the single-berth dock in the spring of 1941, but made few other improvements. In the open season incoming tonnage was handled by troops detailed from the post. During the rest of the year installations in the Anchorage area were supplied through Seward and later Whittier.

The only other port linked with the interior of central Alaska was Valdez, the southern roadhead of the Richardson Highway. Since the road was open only four months in the year, activities at Valdez were seasonal, the port receiving little tonnage during the winter months but discharging as much as 27,000 measurement tons monthly during the brief summer, for shipment by truck to stations as far north as Fairbanks. The prewar commercial port facilities were adequate and labor was provided by garrison troops. In the latter part of 1943, with the discontinuance of the motor transport operation, Valdez was placed on a caretaker status.

Other ports in central and southeastern Alaska, including Cordova, Yakutat, Annette Island, and Sitka, were isolated and were used only for the supply of local garrisons and airfields. Extensive improvement of existing dock and lighterage facilities was not required; labor was provided by civilian longshoremen, where available, and by garrison troops. Like Valdez and the icebound stations, these ports handled insignificant traffic after 1943.

Kodiak was already being developed as a naval base when the first Army troops arrived in April 1941. Initially, two Navy docks, capable of berthing three vessels each, and a privately owned wharf were available. In March 1942 the Army purchased a cannery dock, and improved it to a point where it could handle a large ocean-going vessel. Dock labor was provided by civilian longshoremen until a port company arrived in November 1942. Relations among the Army, Navy, and civilian dock owners were excellent, each making its facilities and labor available to the others.

To the westward, Dutch Harbor stood as the prewar naval bastion overlooking the Aleutian chain. When the first Army garrison troops arrived in May 1941, they used the Navy dock and the commercially

owned Unalaska Dock. The Army took over the latter installation in September 1942 and later completed construction of a new dock and a number of berths for small boats at Captains Bay. Army cargo-handling activities were conducted by tactical troops until December 1942, when a port company arrived. Dutch Harbor loaded or discharged up to 34,300 measurement tons of Army cargo monthly during 1943, and although traffic declined markedly thereafter it remained one of the major Army ports in Alaska.

The largest Alaskan port operation had its origin in the selection of Adak for development as an advance base from which to bring the Japanese-held islands of Attu and Kiska under air attack.44 On 30 August 1942 six troop and cargo vessels, carrying an occupation force of 4,602 officers and men and 43,500 measurement tons of supplies and equipment, arrived at Adak. The landing was unopposed but proved difficult, the uninhabited island lacking facilities of any kind. Troops were lightered ashore by 32 LCPs (landing craft, personnel) and 4 LCMs (landing craft, mechanized) of the Navy transport J. Franklin Bell. A fifty-knot wind and heavy surf caused many of the landing craft to be broached, and their continued operation was made possible only after ATS tugs arrived and towed them back into the water. All troops were pressed into service to manhandle the cargo from landing craft to the high-water mark on the beach. As cranes and tractors were landed through the surf, it was possible to move cargo from the beach to dispersal areas. Cargo was unloaded from lighter to beach until the third day, when a barge dock was improvised by beaching one barge and fastening two others to it as an extension. Unloading was completed on 6 September, and thereafter additional Army and Navy personnel were brought in as rapidly as available shipping and port capacity would permit.

Under the leadership of the post commander, Brig. Gen. Eugene M. Landrum, Adak was developed into a powerful forward air base, a staging area for subsequent expeditions, and the most important port in Alaska. Docks, sorting sheds, and warehouses were constructed, port operations were systematized, and port troops, cargo-handling equipment, and trucks were brought in. From his tactical staff, General Landrum detailed a port commander and subordinate officers, including an ATS assistant superintendent and a harbor boat master. The port commander directly controlled all service and tactical forces engaged in port operations, including ATS officers, port companies, and harbor craft, truck, sorting-shed, and warehouse troops. This improvised port organization proved highly effective and was made a model for other ports by General Whittaker. In April 1943 Adak discharged approximately 130,000 weight tons. The Army had completed a pile-driven lighterage dock and two piers capable of berthing three ocean-going vessels, while the Navy had built a separate dock at Sweeper Cove. Army cargo and a portion of the Navy cargo were handled by two assigned port companies and two others being staged pending assignment to more advanced ports, supplemented by large details of tactical troops.

During the period in which Adak outfitted task forces for additional landings in the Aleutians, the port commander, Colonel Nickell, trained several officer teams

to assist future port commanders in organizing their operations. Using available port and tactical troops, the team set up and trained outport headquarters; organized the harbor by the placement of buoys and set up a system for dispatching landing craft, tugs, and barges; developed ship-to-shore discharge, first with landing craft, then with barges, and finally from docks; and organized the handling of discharged cargo, at first with tractors on the beach and later with trucks at docks, sorting yards, and dispersal areas. After establishing a port operation, the team might stay on or be used in a new landing. Nickell himself moved to Attu as port commander early in its development and later took command of the Shemya port, where he served until his appointment as Superintendent, ATS.45

After the Aleutian Campaign, Adak continued as the most active Alaskan port. It became a transshipment port, receiving supplies from Seattle and distributing them by small vessels and barges to minor ports in the area. Adak handled over 100,000 measurement tons in some months of early 1944, but the general reduction in military strength soon brought a marked decline in traffic.

The advance down the Aleutians brought into operation a number of important ports to the west of Adak. At Amchitka, occupied in January 1943, the port repeated the cycle of lighterage, construction, expansion, and conversion from barge to dock operations that had characterized Adak’s development. Berthing facilities for two ships were completed in June 1943. After discharging a peak of 63,000 measurement tons in September Amchitka handled less traffic, and by late 1944 was receiving only small tonnages, largely by transshipment from Adak.

After Amchitka’s occupation, it was decided to bypass Kiska and take Attu, at the western end of the Aleutian chain. In the spring of 1943 an assault force of 11,000 was assembled on the U.S. west coast and sailed from San Francisco on 24 April in five transports with a strong naval escort.46 The U.S. forces started landing in heavy fog on the beaches of Massacre and Holtz Bays on 11 May 1943. Troops and equipment were carried ashore by Navy LCTs (landing craft, tank), LCVPs (landing craft, vehicle and personnel), and LCMs. The handling of cargo on the beaches was the responsibility of the 50th Engineer Regiment, under Maj. Samuel R. Peterson, the shore party commander.

First landing operations were confused. The assault force had been given no practice in amphibious landings in fog or in darkness and was unfamiliar with Alaskan climate and terrain. Many craft lost their way in the fog, broke down, or were delayed in landing their cargoes and returning to their ships. The unloading of supplies from ships to landing craft was not coordinated, and the system of markers indicating where supplies for each service were to land broke down. Despite the efforts of the Engineers, supplies piled up on the beach and became jumbled, making difficult their segregation and routing to the dumps. Movement from beach to dumps was delayed as tractors

and trailers, operated by inexperienced drivers, broke through the tundra and mired down in the mud beneath. The mountainous terrain and the absence of roads limited vehicle movements from dumps to the interior, compelling the Army to rely on large troop details hand-carrying supplies in support of combat elements.

Despite the difficulties, the initial landing force and a portion of the supplies and equipment were landed by noon of the second day, but much of the cargo had to wait until the weather improved before it was unloaded. Fog not only limited cargo discharge, but also caused a temporary stalemate in the fighting. After several days a slight break in the weather permitted Army and Navy aircraft to go into action, and ground forces began a slow but steady advance in the face of stiff resistance.

As U.S. forces proceeded inland, discharge operations, concentrated largely at Massacre Bay, improved. Larger Navy landing craft, LCTs and LSTs (landing ships, tanks) arrived, carrying cargo from ship to shore until the third week of operations, when ATS tugs and barges moved in to take over lighterage activities. Meanwhile, congestion on the beach was relieved by locating dumps on the banks of a creek and using the gravelly bed as a supply road for vehicle deliveries from the beach. The shore party commander, Major Peterson, temporarily became part commander, two port companies arrived from Adak, and port facilities were placed under construction. When on 31 May American forces captured Chichagof Harbor, the last enemy stronghold on Attu, supplies were flowing across the beach to the interior without serious interruption.

During the course of the Attu campaign, several pieces of equipment proved valuable in the movement of supplies. In particular D6 wide-tread tractors and Athey full-tracked trailers proved indispensable in negotiating the tundra-covered beaches. An innovation was the use of sled pallets to which supplies were strapped. Used as dunnage aboard ship, they could be towed by tractors when put ashore. With some modifications, the pallet was used in the Kiska landings and received extensive use in amphibious operations in the Pacific.

Toward the end of combat operations, Attu moved into the base development phase. Colonel Nickell, who had landed with the initial force as a member of a party to make a reconnaissance for port facilities, arrived from Adak with an officer team to take over port operations; Major Peterson became executive officer. A port organization patterned after that of Adak was developed and the conversion from barge to dock operation was effected. By 10 July 1943 a two-berth dock and a sorting area were completed and the 100,000 measurement tons put ashore since the establishment of the port had been cleared. Tug and barge operations were continued in order to supply outposts around the island’s perimeter, and to transship cargo over sixty miles of water to Shemya after that island was occupied. Attu handled its peak traffic in the winter of 1943–44, discharging up to 42,923 measurement tons and loading up to 22,302 measurement tons monthly. Despite a decline in operations thereafter, Attu remained an active reception and transshipment port.

Shemya, the largest of the Semichi Islands, was the next objective following the Attu landings. In the first months after its occupation in June 1943, two port

companies arrived; docks, airfields, and roads were placed under construction; and all ground force vehicles were pooled to provide transport for port and other base operations. Port development was retarded by the lack of dock construction materials and the limited floating equipment available for shuttling cargo from ocean-going vessels at Massacre Bay, but a breakwater and piers were finally completed, and in the summer of 1944 Shemya was a busy port handling up to 76,000 measurement tons a month. Operations were completely disrupted in November 1944 when a storm washed out sections of the breakwater and carried away the piers.47 Continued bad weather caused the Alaskan Department to place Shemya on a closed winter status until April 1945, when the first vessel of the season was discharged from the port’s roadstead. New pier construction enabled the port to handle Liberty vessels by the end of June, and in the closing months of the war Shemya was again one of the major Alaskan ports.48

The capture of Attu and the occupation of Shemya set the stage for the seizure of Kiska, the final assault operation in the Aleutians. In the spring and early summer of 1943, a combined American-Canadian task force was assembled on the west coast of the United States and Canada. After acclimatization and further training at Adak and Amchitka, the force arrived off Kiska on the night of 14-15 August. The first troops to land found that the enemy had withdrawn unobserved.49

The Kiska operation, the largest undertaken in Alaska, employed 20 troop and cargo vessels, 14 LSTs, 9 LCIs (landing craft, infantry), 19 LCMs, and other craft. Accompanying the force of approximately 34,500 troops were 102,174 measurement tons of supplies and equipment. In the absence of port facilities, cargo and personnel were unloaded directly onto the beach from LSTs or delivered from ship to shore by LCVPs, LCMs, and LCTs. Some days later, ATS barges were towed in by tugs from other Aleutian stations and assisted in lighterage operations. Six cranes were brought in early in the operation to lift and stack palletized cargo and other heavy loads in the sorting yards. A port battalion, less two companies, arrived on a freighter simultaneously with the landing force and was used for discharge activities aboard ship. Unloading on the beach and work in the sorting yards were handled by details from various troop units.

Following the landing, Kiska experienced a brief period of base development. By October 1943 an Army dock capable of berthing two ocean-going vessels, and a causeway leading to it, had been completed. Port operations, previously dependent entirely on lighterage, were now based on ship-to-truck discharge and were considerably speeded up. The reduction of military strength, however, soon brought a decline in activities, and by mid-1944 Kiska was a small outpost rarely receiving more than 1,000 measurement tons a month.

At the end of the Aleutian Campaign, there were in Alaska twenty-eight ports scattered from Annette Island to Nome and Attu. As part of the general reduction of the Alaskan garrison that ensued, the minor ports in southeastern and central Alaska were inactivated or greatly reduced in strength in the winter of 1943–44, and with the exception of Nome the icebound ports were closed out and evacuated in the open season of 1944. These developments, coupled with the general decline in traffic, resulted in the concentration of debarkation activities at a limited number of ports and the development of intratheater transport.

Perhaps the most persistent problem encountered at the Alaskan ports was the lack of floating equipment. From the beginning, there had been a shortage of tugs, barges, and other craft for lighterage, outpost supply, and intratheater transport. Floating equipment, assigned to the various ports and operated by harbor craft detachments, suffered a high mortality rate because of rugged operating conditions and the virtual absence of marine repair and maintenance facilities.50

The harbor craft fleet was built up slowly. The equipment taken over from the Engineers by ATS in August 1942 was augmented, and by early 1943 there were about 190 pieces of floating equipment on charter to the Army in Alaska. At that time, the fleet was cut back sharply by a War Department order to return chartered boats to their owners in time for the coming fishing season so that food essential to the war effort could be provided. Meanwhile, other floating equipment had arrived from Seattle, which had been supplying Alaska with tugs, barges, and other small craft since the spring of 1942. By the end of August 1943, Seattle had shipped forward to Alaska over 450 pieces of floating equipment, an amount sufficient to relieve, but not overcome, the shortage.

Other improvements were provided through the construction of marine repair and maintenance facilities. During 1943 barge ways were constructed at Chernof-ski, Kodiak, Annette, Adak, Attu, and Amchitka, and by early 1944 marine ways capable of performing major repairs on small vessels were in operation at Seward, Adak, and Amchitka. These facilities, together with the assignment of additional craft and small freighters, produced a steady improvement in the floating equipment situation during 1944. As ports were reduced in number and traffic declined, the Army’s floating plant proved adequate for lighterage, outpost supply, and the development of intratheater transport.51

In the final wartime months, vessels arriving in the theater discharged almost exclusively at Whittier, Dutch Harbor, Adak, Attu, Shemya, and Nome. Transshipment of cargo and personnel to and from minor ports was accomplished by a fleet of 176 powered units constituting a service known as Harbor Craft, Alaskan Department. The main burden of this traffic was borne by thirteen small vessels operating on regular intratheater shuttle runs. Ocean-going tugs towing scows operated over the same routes for the

movement of the heavier types of cargo, and also on several shorter and less important runs.52

Rail Operations

Although Alaska is one fifth the size of the continental United States, only two railroads were in regular operation in the Territory in 1940. One, the Alaska Railroad, was the sole year-round transport facility in central Alaska. The other, the White Pass and Yukon Railroad, had only twenty-two miles of line actually in Alaska. Other rail lines were in existence, but had ceased operations. A small section of one of these, the Copper River and Northwestern Railroad, was taken over by the Army in the spring of 1942 and used to haul freight thirteen miles from the port of Cordova to the post and airfields.53

The Alaska Railroad

The Alaska Railroad was a standard-gauge line with approximately 470 miles of main-line track extending from Seward through Anchorage to Fairbanks, and about thirty miles of branch lines to the Matanuska valley and the Eska and Suntrana coal regions. The railroad also operated docks at Seward and Anchorage, coal mines in the Eska region, and a river steamship line on the Tanana and Yukon rivers. Owned by the U.S. Government and operated by the Department of the Interior, the Alaska Railroad was headed by a general manager and manned by a force of approximately 900 civilian employees.

Operated since 1923, the railroad’s equipment was worn and its docks were in a state of disrepair. Track, laid with light seventy-pound rail, required constant maintenance. Operation of the southern end of the line, running through mountainous country, was made difficult by steep grades and heavy snows. Train speeds rarely exceeded fifteen miles an hour, and at mile fifty a tunnel and a rickety wooden-loop trestle made travel at any but minimum speed dangerous. To bypass the difficult southern section, work was begun in 1941 on a twelve-mile cutoff from Portage junction to Whittier, but construction, which involved the boring of two tunnels, progressed slowly.54

Despite its limitations, the Alaska Railroad, with only minor structural improvements and small increases in equipment, was at first able to handle the increased traffic incident to the build-up of the Anchorage–Fairbanks area. But heavy losses of workers, who were leaving to take other jobs, to return to the United States, or to enter military service, caused the railroad’s track and equipment maintenance to fall seriously in arrears. Resulting equipment failures and car shortages, coupled with increased water-borne traffic into Seward, created a bottleneck for northbound traffic in the winter of 1942–43.

To deal with this situation ADC, with the approval of the railroad’s general manager, requested railway troops to augment the civilian force on the line. After a Military Railway Service (MRS) survey had confirmed the need, the Chief of Transportation in Washington arranged for the shipment of the 714th Railway Operating Battalion, augmented by five extra track maintenance platoons and

stripped of certain technical personnel such as train dispatchers, telegraph operators, and signal maintenance and linesmen.55 The entire force of 25 officers and 1,105 enlisted men arrived at Seward from Seattle on 3 April 1943. Headquarters was set up at Anchorage and dispersion along the line begun.56

While responsible administratively to ADC headquarters, the battalion was under the operational control of the general manager of the Alaska Railroad. The railway troops assisted civilian workers on the four divisions of the main line, making possible considerable improvement in the line’s maintenance and operation. The reinforced maintenance of way company, aggregating 9 officers and 739 enlisted men, provided section help along the line, the troops receiving work instructions from civilian foremen through noncommissioned officers. The railroad was assisted also by the transportation company, which provided twenty-five train crews, and the maintenance of equipment company, which supplemented civilian workers at the main shop at Anchorage an51 at other shops along the line and later assumed operation of the new Army shops. The Army also augmented the railroad’s equipment in modest fashion, bringing in seven locomotives, sixty-five freight cars, and a locomotive crane from the United States.57

The Portage—Whittier cutoff was pushed to completion by the Army engineers and civilian contractors, and on 1 June 1943 the twelve-mile line was placed in operation, along with new shop, rail yard, and dock facilities at Whittier. Aside from bypassing the difficult southern section of the main line, the cutoff shortened the rail distance to northern stations by fifty-two miles. Army freight was then routed through Whittier, leaving Seward to handle civilian freight.

The provision of rail troops, the routing of Army tonnage through Whittier, and the small increases in equipment markedly improved the railroad’s performance. In November 1943 the line hauled 66,000 tons of revenue freight, as compared with 36,302 tons in the previous January. During the year the total revenue and non-revenue freight carried by the railroad amounted to 698,978 tons, almost 178,000 tons more than the 1942 figure.58 Deterioration of the line had been halted, and the Alaska Railroad had become a reliable transport facility capable of meeting Army demands.

In March 1944 the improved strategic situation in Alaska, together with demands for railway troops from active theaters, led the Chief of Transportation in Washington to recommend the curtailment of Army assistance, but the railroad’s inability to secure sufficient civilian personnel made it necessary to retain the troops temporarily. The Alaska Railroad, with a combined civilian and military force of about 2,000, experienced its peak year of traffic during 1944, hauling 642,861 tons of revenue freight. By April 1945 increases in the civilian force and declining traffic enabled the Alaskan Department to

make the rail troops available for return to the United States. Except for one track maintenance platoon that stayed on until 27 August, the battalion was relieved, departing Fort Richardson on 10 May.59

The White Pass and Yukon Railroad

The White Pass and Yukon Railroad was a narrow-gauge (thirty-six inch) railroad extending 110.7 miles from Skagway to Whitehorse. The line was managed by a resident official representing three operating companies, whose capital stock was owned by a British firm. Placed in service in 1901, the railroad had undergone little development. Equipment operating on the line in mid-1942 consisted of 9 locomotives, 186 revenue freight cars, and 14 passenger cars, the majority of which were over 40 years old. Track was laid with light 45 and 46-pound rail, for the most part rolled before 1900. Like the Alaska Railroad, the WP&Y owned and operated allied facilities, including the ocean dock at Skagway and a river steamship line out of Whitehorse.60

Operating with limited and antiquated equipment over a rugged route, the railroad was unable to clear cargo laid down at Skagway, and by the fall of 1942 it was fast becoming a bottleneck in the flow of supplies into western Canada. At the direction of General Somervell, who had inspected the line in August, the railroad was leased by the Army, effective 1 October 1942. By this time a railway detachment of 9 officers and 351 enlisted men had been activated and shipped from Seattle, and arrangements were being made to purchase and ship American rail equipment.61

Engineer Railway Detachment 9646A arrived at Skagway in mid-September 1942, set up its headquarters, and after a brief period of instruction took over the operation and maintenance of the railroad. With the continued assistance of the civilian employees, the troops acted as mechanics, engineers, dispatchers, firemen, conductors, telegraphers, section hands, brakemen, and track walkers. Upon the transfer of MRS from the Engineers to the Transportation Corps in November 1942, the unit was redesignated the 770th Railway Operating Detachment, Transportation Corps.62

Under military operation, the railroad carried 14,231 tons in October, about 3,000 tons more than the previous month. It was expected that equipment scheduled for early arrival would further accelerate traffic, but severe winter weather struck

the area in December, and for a three-month period high snow drifts, ice, snow-slides, and sub-zero temperatures made the line’s operation and maintenance a nightmare. Rotary snowplows preceded all trains, but occasionally drifts were too high to cut through and trains were isolated. Ice on the rails resulted in frequent derailment of locomotives and cars, and when trains stopped they froze to the tracks. Traffic slowed to a trickle, and in December and again in February the line was completely immobilized for ten-day periods.

While the troops were battling to keep the line in operation, plans were being made to increase the railroad’s personnel and equipment. In view of increased Northwest Service Command estimates of supply requirements, a MRS survey was made in early 1943, following which the Transportation Corps undertook to provide the additional troops, rolling stock, and motive power needed to handle 1,200 tons daily by May. On 1 April the detachment was redesignated the 770th Railway Operating Battalion, with an authorized strength of 19 officers, 2 warrant officers, and 708 enlisted men. Technical supervision of the railroad, previously exercised by MRS headquarters, was transferred to the Commanding General, NWSC.63

As the weather moderated and additional personnel and equipment were placed in service, rail operations improved. Traffic, virtually all northbound from Skagway to Whitehorse, climbed from 5,568 tons in February to a peak of over 40,000 tons in August. By the fall of 1943 the backlog of freight at Skagway had been cleared and the railroad was hauling all tonnage offered.

During the year 1943 the WP&Y carried 284,532 tons, more than ten times the traffic handled in 1939, and transported some 22,000 troops and civilian construction workers to Whitehorse. The right of way had been improved, 25 locomotives and 284 freight cars had been added to the equipment, and night operations had been initiated. The entire responsibility for maintenance and operation rested with the 770th Railway Operating Battalion, assisted by about 150 civilians.

The second arctic winter experienced by the rail troops again curtailed train operation, but demands for tonnage were now diminishing. Although a significant southbound movement from Whitehorse to Skagway developed in the summer and fall of 1944 as construction forces evacuated their men and equipment, it was insufficient to offset the decline in northbound traffic. The battalion was reduced in strength during the summer, and in November the bulk of the troops returned to the United States. Remaining rail activities were consolidated with port operations at Skagway, and the 330 military and 120 civilian personnel involved were placed under an Army general superintendent. The railroad was returned to civilian management in December 1944, and arrangements were made for the evacuation of equipment and the recruiting of civilian workers to replace the troops.64

Motor Transport Operations

Alaska possessed few highways and lacked land communications with the rest of the continent at the outbreak of war. The road system within the Territory had undergone little development, much of the population in the interior being served by river during the brief summer season. In 1940 there were only 2,212 miles of road suitable for automobile traffic. These highways, concentrated largely in central Alaska, were unpaved, limited in capacity, and subject to seasonal interruptions. Consequently, Army motor transport activities within the Territory, other than those involved in local post supply, were minor.

The Richardson Highway

The principal prewar Alaskan road was the Richardson Highway, leading 371 miles northward from Valdez to Fairbanks over a route generally paralleling the Alaska Railroad. At Fairbanks the road joined the Steese Highway, which extended 162 miles to Circle. The Richardson Highway net was extended by the Army during 1942 through the completion of two branch roads. One, the 147.5-mile Glenn Highway connecting Palmer with the Richardson Highway below Gul-kana, made possible diversion of some freight from the Alaska Railroad. The other, the 138-mile Tok Junction–Slana cutoff extending from four miles above Gulkana to Tok Junction on the Alaska Highway, reduced the trip from Valdez to Tanacross and Northway airfields by about a hundred miles.